6

CUSTOMER-FOCUS STRATEGY 4: GOOD ENOUGH IS NO LONGER GOOD ENOUGH

QUALITY CAN BE A potent weapon, but only if you know how to use it. Most companies don’t. As soon as they’ve beaten the competition, they consider themselves “good enough.” But in today’s world, no company—no matter how far ahead of the competition it is—stays good enough for long. Look what happened to McDonald’s. Their growth has stalled, and Chick-fil-A is on its way to becoming the third-largest food chain in the United States by 2020.1

How did this happen? Chick-fil-A focuses on the kind of quality that today’s customers care about. Their motto is “Food is essential to life, therefore make it good.” They buy small birds that yield juicier meat and they have perfected its seasoning, hand-breading, and pressure cooking in 100% refined peanut oil. Their birds are raised in barns, not cages, on U.S. farms. They use only 100% real, whole breast of chicken, without fillers, added hormones, or steroids. By the end of 2019, the chickens will be raised without antibiotics. Most of their produce is freshly delivered to their locations.2 Customers love spending on Chick-fil-A. An average location earns $4.4 million in revenue per year, compared to McDonald’s $2.5 million—even though Chick-fil-A is closed on Sundays.

Good enough is no longer good enough in any industry. Even advertising and gimmicks as successful as McDonald’s toys and Happy Meals are no longer enough to bring in customers. You have to give customers what they really want, and earn their trust. Millennials, Gen Z, and even some boomers trust peer reviews more than brands and advertising. These customers don’t care what celebrities and advertisements say. When they want to know about product performance, quality, or service, all they have to do is look online. Their peers will tell them what they want to know—and answer their questions, too.

If a product has a problem, each peer review will describe the customer’s experience with it, in detail, immediately. For example, Samsung’s Galaxy Note 7 was a flagship smartphone that received excellent reviews from third-party reviewers before its launch. But some early customers reported that their phones caught fire or exploded within a few days of product launch in August 2016.3 Social media spread the story—soon airlines were banning the phones or making passengers turn them off until they deplaned. Within a few months, Samsung had discontinued production and recalled 2.5 million phones, but when some replacement phones exploded or caught fire, too, Samsung’s global market share for premium smartphones declined from 35% to 17%. During Samsung’s debacle, the iPhone’s market share jumped from 48% to 70% for premium products, and Chinese smartphone manufacturers like Huawei were quick to seize the opportunity to make significant gains as well.4 So take quality seriously. If your products don’t perform, your customers will find out from their peers—instantly—and your reputation may never recover.

To win with quality, set standards that customers can’t resist and the competition can’t beat, and then keep improving. Many companies make the mistake of thinking that quality means only the end product or service seen by the customer. Those who win with quality know better; they optimize their entire operations for quality. Customers may never see or smell Chick-fil-A’s clean barns or see the way its employees handle the birds, but those things contribute as much as the cooking to what customers love about Chick-fil-A’s delicious meals. Doing this kind of thing may mean challenging long-held perceptions in your company or industry. Do it anyway.

If you don’t think your company needs to change, ask yourself these questions.

• How do customers view the quality of your company’s products and services?

• How much importance does your company leadership attach to quality? Does leadership view quality as a game changer or as more of a placeholder?

• How hard do your internal organizations try to improve quality and delight customers?

Your company’s survival depends on your answers to all three questions. In a world where peer reviews have more credibility than advertising or third-party endorsements, winners make every effort to improve quality. Doing that starts with getting honest feedback and then improving products in response to it. If your organization is dedicated to working with customers to set standards your competition can’t meet, your company will wield the weapon of quality and will win. The steps in the process are described here; the specifics are up to you.

STEP 1: FOCUS ON QUALITY, NOW

Many U.S. companies got broadsided by high-quality Japanese products in the 1980s. But U.S. manufacturers (like those in the auto industry) didn’t get the message. They remained convinced that they could compete on price. So they responded not with higher quality but with cost cuts and—when that failed—by getting imports restricted. Neither worked, and American manufacturing never recovered—not because American companies were paying their workers too much money but because American companies were paying too little attention to quality.5

Today, some U.S. companies have improved the quality of their products. However, it has come at a cost. GM, for example, lost to Toyota for a while, but GM is making quality vehicles now. It has won several JD Power awards, and test rides show that GM vehicles perform as well as any imported vehicles. But their vehicles are becoming expensive, and Toyota still outsells them.

So what’s the answer? Whatever industry you’re in, don’t wait to focus on quality until a competitor does. Do it now, do it first, because your customers want it. A me-too offering later on may not get them back.

Quality Doesn’t Have to Be Expensive

Millennials and others want only the best, but they don’t want to pay premium prices for it—even for Apple products. Even though this is well known, however, many companies try to achieve the quality that customers expect and the standards that regulations demand by investing in expensive plants and equipment, which of course raises their costs. That’s the wrong approach, and it doesn’t work anyway.

To achieve quality without prohibitive costs, you have to think outside the box. When Tim Cook was asked why Apple products were so expensive, he replied, “Instead of saying, ‘How can we cheapen the iPod to get it lower?’ we ask, ‘How can we do a great product and do it at a cost that enables us to sell it at the low price of $49?’” Some people wondered why Apple did not offer a Mac for less than a thousand dollars. Cook’s response was, “Frankly, we worked on that, but we concluded that we couldn’t do a great product. And so we didn’t. But what we did do is we invented the iPad. . . . Now all of a sudden we have an incredible experience that starts at $329. Sometimes you can take the issue or the way you might look at an issue and solve it in different ways.”6 That’s great advice, and the iPad was a great idea.

Other industries, too, are finding innovative ways to provide affordable quality. Look at discount food retailer growth in Europe. Most of us associate the word discount with low quality. However, discount food retailers in Europe adopted a different strategy to win customers. Two grocers, Aldi and Lidl, concentrated on offering fewer foods but at lower prices. Their first stores were small and had a low-cost feel, but customers kept coming, because they were getting better value there. Then, in 2000, Aldi and Lidl began offering higher-quality products at lower costs than the competition did. Their products beat branded products in both head-to-head tests and independent quality reviews. In customer surveys, shoppers indicated that Aldi’s products were better than national brands in categories such as milk, eggs, canned goods, and frozen foods, despite the fact that their prices were significantly lower.

Since then, both companies have slowly expanded their product offerings to include packaged goods such as baby food, breakfast cereal, and even personal care and beauty care products. Customers typically started by trying a few products, such as eggs and milk, and then, once they were satisfied with their quality, quickly moved on to other products in the store.

Soon, people from all income levels, attracted by the higher quality, began patronizing the stores. The discounters opened bigger stores and offered more variety. Now they have fresh produce, baked goods prepared on site, and some organic and gluten-free choices in both categories. Many have refrigerated sections and the look and feel of other grocery stores. However, they are careful to offer a better shopping experience than the competition’s: longer opening hours, faster checkouts, more space, and better lighting.

And with all this, discounters still kept their prices 15% lower than established-grocery private-label products and 50% lower than branded products.7 They were able to do this because they worked with fewer products and a select number of food manufacturers, which—combined with their large volumes—allowed them to buy in bulk at favorable prices. Typically, Aldi and Lidl work with regional manufacturers, too—purchasing pasta from Italy, for instance—to get the best quality. And whenever they can do so without lessening quality, they remove operational costs.

Millennials drove the growth of discounters. They prefer discounters over regular grocers in most markets. Millennials, as discussed earlier, are not brand conscious. They inherently trust discounters more than regular grocers. Then, when discounters offered higher-quality products, a broader assortment, and improved shopping experience while maintaining lower prices, baby boomers and Gen Xers started visiting the stores.

These days, food discounters have taken over the grocery market in Europe. In Norway, Germany, and Denmark, they have captured a 50% market share. In other European markets, such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Ireland, and elsewhere, they are proliferating. Discounters entered Ireland in 2000, and by 2015 they had a quarter of the market share (figure 22). Since Aldi and Lidl became big in the United Kingdom, regular grocers have seen their margins shrink from 5% to less than 3%. And the discounters kept growing. By 2017, Aldi had more than ten thousand stores in eighteen countries and more than €50 billion (about $56.5 billion) in revenue. Lidl had ten thousand stores in twenty-eight European countries.

Now discount grocers are starting to make a dent in the U.S. food retail market. Aldi opened its first U.S. location in 1976, in Iowa; by 2017 it had 1,700 stores, and it plans to open eight hundred more by 2022. Lidl opened fifty-three stores on the U.S. East Coast by the middle of 2018. With every expansion of discount grocery stores, U.S. customers benefit from higher-quality products. Are Whole Foods and other grocers with high prices prepared to compete? Aldi and Lidl will likely take over the U.S. grocery market with higher quality and lower prices, a strategy that does better than the “everyday low prices” offered by Walmart.

FIGURE 22 European discount grocers’ market share (percent). Source: Planet Retail, embedded figure, in Rune Jacobsen et al., “How Discounters Are Remaking the Grocery Industry,” BCG, April 11, 2017, https://goo.gl/7b9jvn.

Quality Is Essential for All Industries

Most people assume that “quality” refers only to products, but it applies to service, too, and companies in all industries provide examples.

Qatar Airways, for example, focused on quality and won business class customers from competitors who had been in the industry far longer than they had. Skytrax ranked Qatar Airways the world’s best airline four times in the past seven years, and the airline has won numerous other awards, including World’s Best Business Class and Best Airline Innovation. Even Qatar Airways Cargo won the Global Cargo Airline of the Year award.8 Clearly, this airline takes quality seriously! It focuses on business passengers, offering them luxuries like space, high tech of all kinds, and seats that can recline to the point of complete flatness. First class is even more luxurious; some have said it’s like flying in a private jet. In both first class and business class, Qatar passengers eat whenever they want—at their convenience, not the crew’s. While other airlines are scrapping free meals, Qatar Airways is promising a “new age of airline dining.” Service extends to the airport. Doha International is the world’s sixth-best airport. It handles half as many passengers as JFK, yet 86.34% of its flights left on schedule.

Qatar Airways keeps raising the bar, and other airlines are finding it difficult to catch up. Despite blockades by neighboring countries in 2017, Qatar Airways grew revenue by 10.4% and profit increased by 21.7%.9 However, none of this is enough in today’s world. Even Qatar Airways, number one in the world, needs to keep improving or another upstart will slip in and start stealing its market share.

One way Qatar could improve is to offer its economy passengers more. If it doesn’t, rivals who do offer their economy passengers more, such as Singapore Airlines, may start stealing Qatar’s customers. Singapore Airlines has well-trained cabin crews in economy, and it serves excellent food and provides comfortable seats in that class. They know that all customers—rich or poor, old or young, from the third world or the first—appreciate quality.

It’s not enough to be the best. Any company has to stay the best. In Qatar’s case, that means serving its economy class as well as it serves its business class.

Quality Is in the Eye of the Beholder

Although all customers appreciate quality, their definitions of it differ. What’s high quality to one segment may be mediocre to another. For example, business class passengers assume that they will have comfortable seating, clean bathrooms, palatable food, and respectful service during the flight. Given how most airlines treat their economy class passengers, most of them would be thrilled to have all these things. But Qatar doesn’t bother; they don’t train their economy class crews as thoroughly as they train the crews in business class. The food in economy is average at best. In the long run, this will hurt Qatar. Singapore Airlines treats its economy passengers so well that people are willing to pay a premium for it.

All businesses—not just airlines—need to meet the needs of all their segments; if they don’t, their competitors will. Android devices are an apt example. In 2005, Google acquired Android and, because they were late to the market, made the platform free to all smartphone manufacturers to facilitate faster adoption. Millennials and tech-savvy customers loved how easy it was to customize Android devices—and how much better than the iPhones they were at taking pictures, using apps, typing, checking mail, and getting directions. While iPhones remain popular with boomers and not-so-tech-savvy individuals, Android appeals more to the younger generations.

Gartner estimated that Android had 54% of operating system share for all devices (mobile, laptop, and tablet) shipped by manufacturers worldwide in 2015. Apple’s iOS and Windows had only 12% each.10 Microsoft, realizing that its handheld devices had lost the quality war, eventually dropped its Windows Phone and now has no presence in the largest computing devices market, smartphones. Windows might have held on to its smartphone market if it had realized sooner that customers and manufacturers define quality very differently.

STEP 2: SET STANDARDS THAT CUSTOMERS CAN’T RESIST

Customers are thinking about their needs; most manufacturers are thinking about meeting regulatory standards. But regulatory standards are always a few steps behind evolving customer needs, so merely meeting regulatory standards is never enough. The United States has no regulations for internet companies, but Facebook is losing European subscribers and younger customers because of its violations of their privacy. Meanwhile, Apple is touting its respect for users’ privacy and winning customers’ trust. Similarly, while Washington is still debating whether global warming is real, millennials (and others) are demanding environmentally friendly products. So don’t wait for regulations to make you change your standards. Think about quality from the customer’s perspective, and then think about how you will raise and live up to your own new standards.

As we have discussed, customers’ needs are changing continually. Don’t become complacent. Push for improving standards that customers will value—standards that set you apart from the rest of your industry. For example, Southwest Airlines has the highest customer loyalty among all U.S. airlines, and they only serve economy customers. Customers rave about how well Southwest employees treat them and how easy it is to deal with them. This is because Southwest treats its employees well. It values its employees and its customers, and this keeps both groups happy.

Southwest employees do everything they can to make flying easy and entertaining—and all service industries ought to learn from them. If you are in a service industry, customers will judge you by how well your employees treat them. Apple, Google, Disney, Starbucks, and others are famous for quality because they make every effort to set standards that customers can’t resist and then continue to improve on those standards. Successful business-to-business companies do the same.

But most companies look at the value of quality improvement very differently. They see it only from their own perspective and not from the customer’s perspective. For example, biological and particulate contamination is a significant concern for medical patients. Though the medical devices industry has addressed biological contamination, small particles remain a source of enormous waste within the pharma world and represent a substantial risk in patient care. If any company could significantly reduce or eliminate particulate contamination, it would gain a significant competitive advantage, because the risk to patients of developing severe allergic reaction due to particles would be significantly reduced.

Even so, medical devices companies thought particle-free products would be impossible to make. But one of our clients, a small company we’ll call MediDevi, which made caps for medicine vials, decided to try. When a vial became contaminated, nurses usually noticed small particles in the fluid and discarded the whole vial. This cost pharmaceuticals millions of dollars in lost drugs and product recalls—and all because of a cap that cost a few cents!

MediDevi used a mechanical process developed decades ago to produce the caps, and the company had been getting complaints about tiny particles in its caps—plastic, lint, dirt, or hair that stuck to the caps, sometimes contaminating whatever was in the vial and sometimes causing allergic reactions in patients. In addition, discarded drugs and pharmaceutical product recalls were costing millions of dollars. After the MediDevi sales organization discussed with pharmaceutical companies the benefits of better caps, they decided to try to develop caps that would keep the vials particle free.

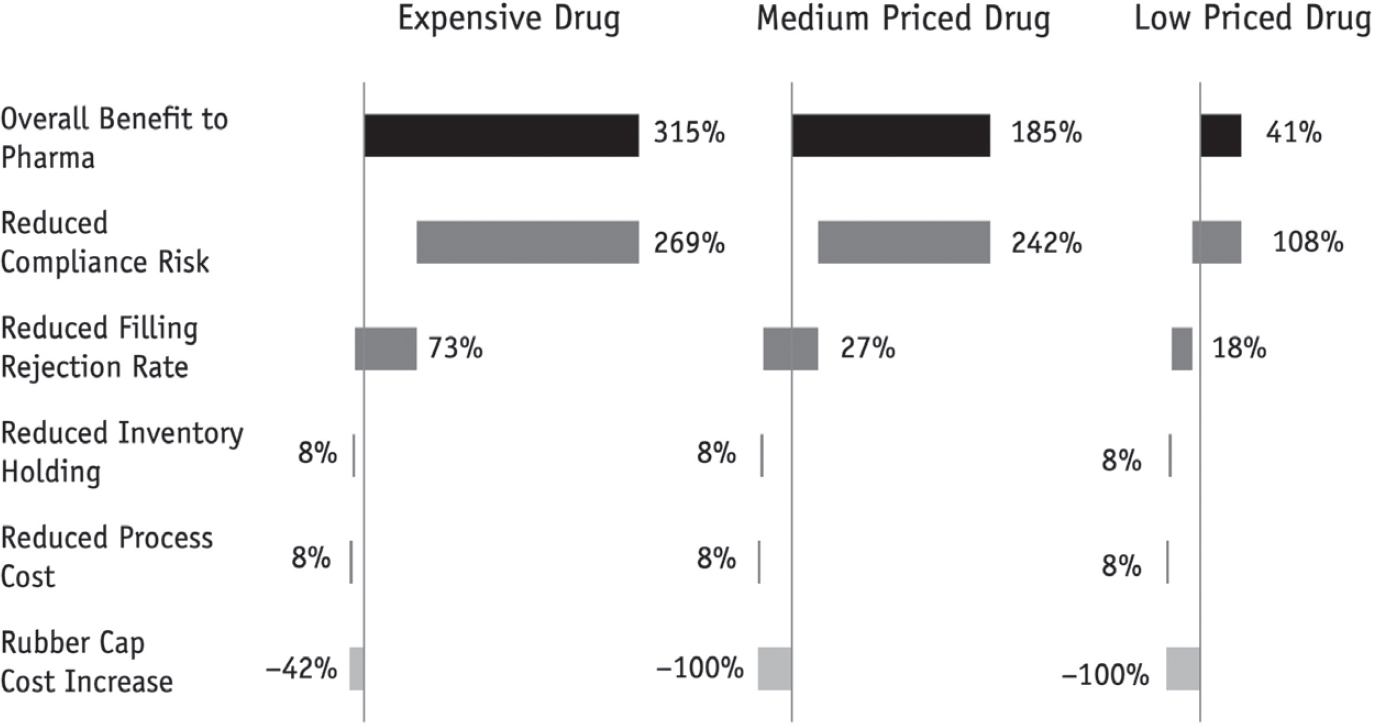

MediDevi realized that caps that kept vials particle free could be a game changer in the industry. They asked our firm to compute the value and costs of reducing particulate contamination. Using medical research and reports from the Food and Drug Administration, we realized that reduced compliance risk (recall) and rejection rates would more than make up for the increase in costs that a particle-free manufacturing and supply chain would incur. The benefit varied with the drug price—the more expensive drugs would see higher benefits (see figure 23). Our analysis estimated that the rubber cap cost would increase by 42% for the expensive drugs but that the reduced compliance risk rate (269% of the cap cost) and filling rejection rate (73% of the cap cost) would more than make up for it.

Benefits from reduced inventory holding and processing costs were marginal, but overall we found that the company would save 315% of the rubber cap cost. In other words, if the pharmaceutical company was spending $10 million on the rubber cap before quality improvements, the rubber cap cost would go up by $4.2 million but they would save $31.5 million because of the improved quality. We estimated the overall benefit to be 185% for medium-price drugs and 41% for low-price drugs.

However, MediDevi’s supply chain organization did not understand the benefits at first. They were incentivized to reduce cost and increase throughput but had no incentive to reduce particulate contamination. And if they focused on removing particulate contamination, they’d have to change the fundamental design of their plants, which were designed to produce as much as possible, not to provide the highest quality. Even so, MediDevi insisted on the changes, persisted, and achieved the impossible: contamination-free caps. Customers couldn’t stop ordering, MediDevi’s revenues soared, and the competition found it difficult to match MediDevi’s higher quality. Competitors had to deal with significant rejections and found the process unsustainable.

FIGURE 23 Benefit to pharmaceutical companies of reduced particulate contamination, expressed as a percentage of rubber cap cost. Source: Three S Consulting.

STEP 3: OPTIMIZE MANUFACTURING FOR QUALITY, NOT OUTPUT

Most manufacturing operations are like the medical devices industry in valuing throughput over quality and in following a century-old system of quality control. Though quality control is part of the manufacturing process, it’s almost always an afterthought; inspection is done only at the end of each stage. The design philosophy is focused on squeezing as much production out of a plant as possible. The objective is to lower costs. Thus, many low-quality products are made, on the assumption that any falling below minimum standards will be rejected during the inspection and then discarded or fixed.

However, relying on inspections at the end of the production process and doing checks at each stage can lead to defective products. And as the exploding Samsung Galaxy shows, even a small number of lemons can kill a flagship product and dent a company’s reputation for good. In addition, inspecting every single product costs too much to be practical, even when the inspection process is automated. Even so, any poor-quality product that inspection misses can lead to a product recall or a bad review on Amazon or social media. The effects of recalls and bad reviews last a long time.

The philosophy should be that no poor-quality products will ever be produced, period. This requires a different manufacturing mentality. It means redesigning your manufacturing process so that you only produce products that meet your new high-quality standards. This is completely different from relying solely upon inspections at the end of the process—but it’s time to make the change, no matter how difficult or expensive it seems in the short term.

That’s what MediDevi did. A series of experiments showed them that once contamination had entered the manufacturing process, it was impossible to get rid of it, even with state-of-the-art equipment such as clean rooms. So they ended up completely changing their manufacturing process, and that finally resulted in particle-free caps.

MediDevi learned a lesson that few companies master: you have to fix quality problems at the source of the problem, not at the end of the process. That’s the only method that works. In MediDevi’s case, the clean room environment at the end of the manufacturing process did little to reduce contamination levels (figure 24). Our experiments showed that the number of particles larger than 25 microns in size (in a 10 square centimeter area) was two in molding, seventeen in cutting, twenty-one in washing, and nineteen in final washing. There were two insights from the experiments: first, that the cutting process introduced contamination, and second, that the washing processes didn’t remove these particles and in fact ended up increasing them. MediDevi had to stop the contamination that was entering during the cutting and washing processes.

FIGURE 24 Particulate contamination after each production stage. Source: Three S Consulting.

Once they changed the cutting and washing processes, MediDevi found that optimizing production for quality actually reduced costs, because significantly fewer caps had to be discarded and inspections took so much less effort. MediDevi pleased its customers, outstripped its competition, and increased margins by focusing on quality.

But most companies today aren’t making this change in thinking. They continue to focus production on throughput. They still believe that the more they produce, and the lower the production costs, the more they will please customers. That’s no longer true. Focus on throughput results in poor-quality products that run the risk of recall and negative reviews. The cost of low quality is high. A better approach is to optimize manufacturing for quality so that products consistently meet quality standards. Producing high-quality products with zero rejection rates can be surprisingly cheap. It makes no financial sense to optimize manufacturing for output.

STEP 4: DON’T BE AFRAID TO CHALLENGE INDUSTRY NORMS

Manufacturing processes in most companies are set up to follow industry norms, which rarely improve quality standards. Even if following industry norms (or whatever the industry is doing to set standards) works for a while, staying competitive requires a company to continually evaluate its standards against changing customer needs. Instead, most stick with manufacturing processes that can’t produce products that measure up to their customers’ new needs. Then, if they realize that they’re not meeting the new needs, most merely automate their old systems rather than using their customers’ requirements to design new systems.

For example, the MediDevi manufacturing process mirrored their pharma customers’ manufacturing requirements, with clean rooms and garments, at a significant cost. Pharma customers loved the manufacturing process. However, it did nothing to improve quality or reduce particulate contamination. What worked for pharma customers didn’t work for their suppliers. When MediDevi first tried to solve the contamination problem, therefore, they sent a team to inspect a counterpart in Japan. The team came back with a recommendation to invest in a new high-tech automated facility—at a cost of millions of dollars—but initial results did not show any significant improvement in quality. MediDevi already produced better quality caps than their Japanese counterparts or fully automated manufacturing. MediDevi had to think outside the box to improve quality.

As they worked through the problem, many widely accepted industry standards were found to be of little value. Washing with water is a traditional cleaning process in the pharma industry. However, analysis showed that washing was appropriate for biological contamination but increased particulate contamination—rubbing during washing created more particles. So MediDevi tried changing the last cleaning step from water to air drying. That removed smaller particles more efficiently. Similarly, commonsense improvements such as requiring employees to wear gowns and to follow simple hygiene and cleaning practices reduced particulate contamination just as well as the very expensive, industry-norm clean room did. At first, MediDevi’s manufacturing team resisted these changes because they were so radically different, but once they tried them and saw the results, they were convinced. And their customers loved the contamination-free caps.

If challenging industry norms will improve the quality of your products, make the changes. It will be difficult for regulators or customers to argue with the results—and for competitors to catch up with you.

STEP 5: THINK SUPPLY CHAIN

Historically, companies have measured and tested quality only within their own four walls. For example, Toyota, Honda, and other car manufacturers focused on the quality of their in-house manufacturing but didn’t subject the air bags sent to them by Takata to rigorous enough testing—a fatal error. Twenty people in Honda cars died when the Takata air bags exploded upon inflation.11

Any chain is only as strong as its weakest link—and that’s as true for supply chains as for any other kind. Product quality has to be strong all along the chain, as Takata’s failure shows. The exploding air bags put the reputation of Toyota, Honda, and several other auto manufacturers at risk. Honda executives had to testify before Congress, cut their profit forecast by more than $400 million due to recall-related costs, and ask their CEO to step down.

To achieve higher quality standards, it’s not enough for companies to maintain standards in their own plants—they have to work with their suppliers and customers. MediDevi found that even all the improvements at their own plants couldn’t reduce contamination until their pharmaceutical customers changed their processes. The pharmaceutical companies opened and inspected all incoming products, including of course the caps. Then they tested and washed the caps before putting them on their vials. So all the benefits of producing cleaner caps were lost when their cartons were opened and exposed to unclean warehouses. The only way to keep the caps clean was to put them straight into the pharmaceutical companies’ manufacturing process, without inspections. This was a significant change for the pharmaceutical companies, and some didn’t agree with it. As a compromise, MediDevi proposed sending samples via FedEx for testing, a compromise that worked for both parties.

Over the course of two years, the optimization and changes to the manufacturing process reduced contamination by a factor of one hundred. MediDevi opened a whole new market with the high-quality product and its associated revenue source. Due to the drop in throughput, the cost for the client increased, but their customers were more than happy to compensate them. Overall cost reduction and patient benefits were immeasurable. Competitors tried to copy the visible changes in machinery and process but failed to fine-tune the overall process to achieve MediDevi’s higher quality standards. MediDevi won because they focused on their customers’ needs and had the courage to make big changes all along the supply chain.

It’s impossible to improve quality by focusing only on your own operations. You can achieve higher levels of quality only by considering customers and suppliers as part of your manufacturing system.

WINNING WITH QUALITY

As we discussed earlier, more and more customers are reading peer reviews on Amazon and other sites before buying products or services. They’re looking at product performance, service, and quality issues, and they believe what their peers tell them—not companies’ claims or advertising. In this environment, all products and services are judged on their own merit, according to how well they work for customers. Improving quality is a sure way to get repeat business and to attract new customers with favorable reviews.

Despite how well known all this now is, however, corporate leaders continue to use quality as a placeholder. As long as they’re doing as well as the competition in quality, they focus on other strategies to improve stock price. Some companies, such as Volkswagen and Takata, have even been caught lying to their clients and to regulators about quality performance. It’s hard for a company—even one as well loved as Volkswagen used to be—to win back its reputation and customer trust after something like that. Volkswagen sales have yet to regain their prescandal levels.

Other companies—such as discount grocers and international airlines—are wielding quality as a weapon and using it to win customers from competitors. These companies have disproven the myths that higher-quality products cost more and that automation somehow improves quality. Discount grocers have shown that higher quality can be achieved at lower prices. Many high-volume, low-cost wines are winning with quality, because producing in quantity can ensure consistency and higher quality levels.

And customers find out about quality not through expensive advertising but through peer reviews. These are very different from professional reviews, and they change far more frequently. Take, for example, noise-canceling headphones. They are becoming popular as more and more people are using them to listen to music in planes, in open offices, and even while mowing lawns. Bose and Sony are the leading manufacturers, with similarly priced products. Third-party reviewers consistently rate Sony higher than Bose in sound quality and features.

However, customer reviews on Amazon tell a different story. Customers prefer Bose because Sony headphones break easily—and when they do, no one is willing to spend another $300 on them. Bose headphones don’t break and are more comfortable, though the sound quality is not as good as Sony’s. Sony is trying to catch up, but Bose keeps getting better, not only keeping its current customers but also attracting new ones with new features like Alexa voice control. That’s what you have to do to win with quality: keep improving standards to keep delighting your customers.