Conclusion

CHOOSING AND IMPLEMENTING THE STRATEGIES

WE’VE DESCRIBED THE DIFFERENT customer-focused strategies, but how do you choose and implement the ones that will work best for your company? Not all strategies are appropriate for every company. You have to select the ones that best address your customers’ needs and then figure out how to get your organization to support and implement these strategies. This is not easy, as many of the changes entail a radical departure from current practices. Even when leaders understand the benefits a customer-focused strategy will bring to their business, many are still reluctant to change. They don’t want to rock the boat during their short stay at the helm, so they cling to old strategies until customers disrupt their company—and sometimes even after that.

To see how this all plays out at an actual company, consider this true story. I received a call from the strategy officer of a leading facilities management company—let’s call them FMP. They were about to lose their biggest client, a large New York bank that gave them half a billion dollars’ worth of business each year. FMP maintained and managed the bank’s offices, branches, warehousing, and other facilities. FMP took care of almost everything physical: cleaning, security, catering, moving people from one office to another, project management for office renovation, and much more. But the bank had grown increasingly frustrated with the job FMP was doing and, when the bank threatened to cancel the contract, FMP’s strategy officer realized he had to do something. But what?

The bank had turned its facility management over to FMP, assuming that the cost of taking care of its spaces would thereby go down. The bank figured FMP would pay lower wages, for instance, thus reducing cost to the bank. But the charges kept going up every year. FMP did pay its people lower wages, but it charged the bank for every little thing its workers did, including extra costs for extra services. If, say, someone at the bank called FMP to get coffee grounds off the rug after a workday spill, FMP sent someone in immediately—and charged the bank heftily for the service.

The trouble began when the bank executives came under pressure to reduce costs. They changed the contract with FMP from a per-service fee to a fixed fee and stipulated that the fee must decrease by 5% to 10% each year. FMP signed the new contract but quickly realized that they were losing money—a lot of money. So FMP cut back on its services, not just in its response to calls from bank employees but also in regularly scheduled things. For example: FMP began cleaning bank branches only three times a week rather than the former five. These cost-cutting changes enraged the bank. It was at this point that the bank threatened to end the contract and FMP called us.

The first step in fixing the problem was to choose the right strategy, and for that, we needed to understand FMP’s customers and their needs. This included all their customers, not just the bank. As it turned out, FMP was having the same kinds of troubles with all their customers. Without a new service model that met their customers’ needs, fast, they would be disrupted. (Recall the lesson of chapter 5: customers won’t wait.) After analyzing FMP’s contracts with customers, we found that traditional contracts with a small portion of profit at risk represented only 45% of FMP’s revenue (figure 27), and even that was decreasing. Contracts with a majority of profit at risk made up 40% of FMP’s revenue, and the remaining 15% of revenue came from fixed-price contracts. Both the latter contract types were increasing in number.

To reduce costs, you have to understand what’s driving them. As we analyzed FMP’s costs, we realized that close to 85% of costs came from third-party providers such as janitorial services, security services, cafeteria operations, and the like. Further analysis revealed that these costs were driven by labor and that FMP had already aggressively negotiated the pricing. These providers were already paying their employees close to minimum wage and—not surprisingly, given that they were in New York City—were having retention problems. Wages couldn’t be lowered any more, and in some cases they had to go up.

FIGURE 27 Changing customer requirements for outsourcing providers. Source: Three S Consulting.

The only way to reduce costs was to get more work done in the allotted hours. If you’ve ever hired contractors, or just watched road crews, you know that they spend a lot of time standing around, waiting for material, for other crews, for equipment. Third-party-provider crews were also spending a lot of time waiting, as well as traveling from site to site. We realized that by reducing downtime, wait time, and travel time, FMP could significantly reduce costs. To do this effectively, FMP would have to schedule and optimize routes across customers. For example, in New York City, FMP had customers in the same high-rise as, or just across the street from, the bank. If they coordinated scheduled work so that service providers could quickly move from one customer to another, they would get more done during each shift.

We recommended that FMP give each provider handheld terminals, enabling FMP to guide providers from one work site to another, as Uber does with its drivers. Initially, this change would be a lot of work, but by making the change, FMP could meet the bank’s demand for reduced costs and gain a significant advantage over competitors.

So far, so good. But after selecting a strategy, you have to implement it. This is almost always tricky, and so it proved to be in this case. The FMP leaders balked and refused to invest in the changes, believing that their customers had no choice. But that belief was wrong.

Fed up with FMP’s poor service, high costs, and refusal to change, the bank began hiring its own people to manage the facilities. FMP’s margins continued to go down, and their conflicts with customers continued to go up. Not surprisingly, organic revenue stopped growing. As of this writing, FMP is trying to save the situation with one of the outdated strategies we discussed in chapter 2: buying competitors. But it’s only a matter of time before an upstart completely disrupts the industry with a new service model.

To get a sense of how skillful your company is at choosing and implementing customer-pleasing strategies, ask yourself these questions.

• What customer-focused strategies would be appropriate for your company? Why?

• How effective are leaders at implementing these strategies and empowering employees to do so?

If you are very effective at identifying and implementing customer-focused strategies, then your customers will help you disrupt the current providers. You are set up for growth and success. If you are not, you have to identify and implement customer-focused strategies quickly. Otherwise, customers will disrupt you.

SELECTING THE RIGHT CUSTOMER-FOCUSED STRATEGIES

This book details five primary customer-focused strategies: service, personalization, speed, quality, and reinvention. As the FMP example shows, sometimes a portion of a strategy—in FMP’s case, changing the service model, as discussed in chapter 5—is all you need. To identify what’s appropriate for your business, begin with customer needs, then find unique ways to address those needs. What will work for one company may not work for others. It all depends on what you’re offering and the customer segments you’re targeting. For example, in the apparel industry, Zozotown, the Japanese retailer, wins through personalization (chapter 4), whereas Zara wins through speed (chapter 5). They’re targeting different segments. Sometimes a combination of strategies works as well. Amazon employs both service (chapter 3) and speed (chapter 5) to address their customers’ needs.

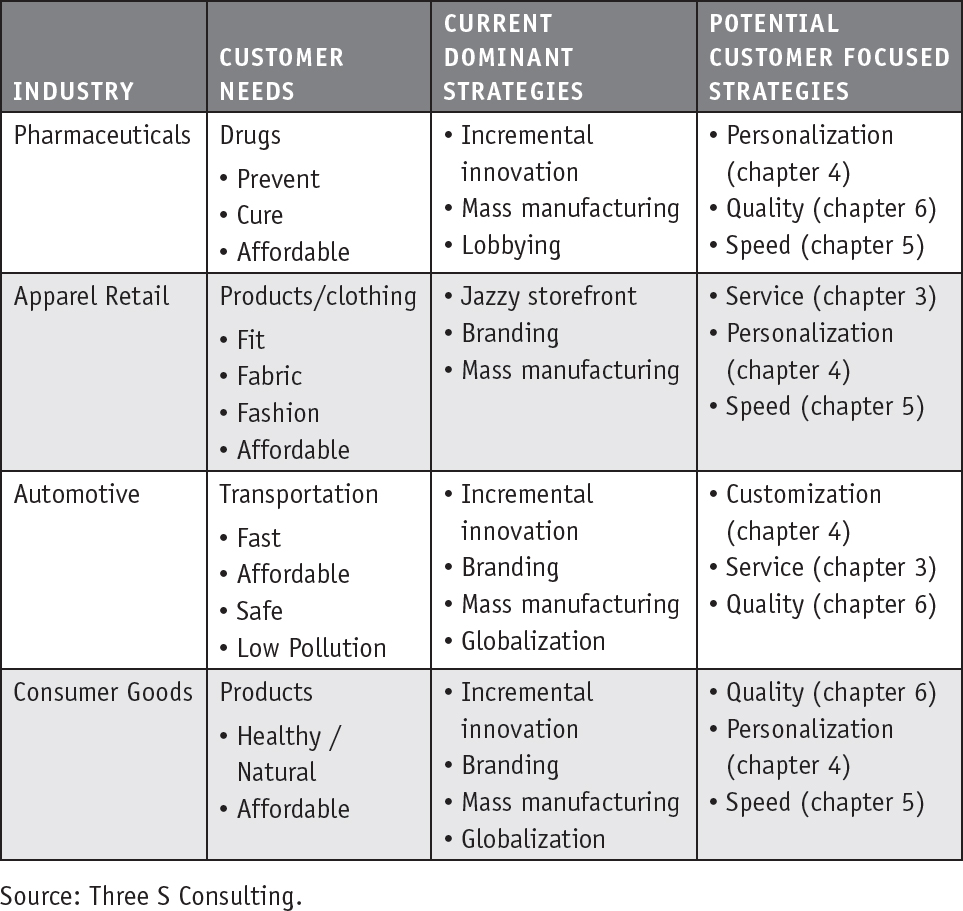

Table 3 highlights the kinds of strategies that companies in different industries typically use now, and those that would be more appropriate. Note that these are not rules, just what is most likely to work in a given industry. Other strategies from the book may work just as well, if not better. The important thing is to choose based on customer needs and segments.

TABLE 3

Potential Customer-Focused Strategies by Industry

To show how companies in different industries might choose their strategies, let us start with table 3 which summarizes customer needs, current dominant strategies, and new strategies for a few industries.

Pharmaceuticals

Customers want to be healthy and are looking for affordable prevention and cures. They desire a healthy life. Three strategies could deliver on those needs: personalization (chapter 4), quality (chapter 6), and speed (chapter 5). For some segments, a combination would work best.

• Personalization in medicine can be based on genetics or on patient history and prognosis. The industry has already discussed using genetics quite extensively; other ways of personalizing medicine haven’t been talked about as much. Most medicines are prescribed based on the patient’s illness, but many are overprescribed or inappropriate. A study by the Telegraph in the United Kingdom states that millions of people take a statin (cholesterol medication) needlessly.1 And even when the medicine is appropriate for the patient, dosages tend to be standardized. Finding the right dosage and combination of drugs based on an individual’s medical history, speed of recovery, or reaction to the medicine could be a game changer. More personalization has huge potential benefits for patients, such as bringing them quickly back to health, avoiding complications, and preventing future disease.

• Quality continues to be an important factor for the pharmaceutical and medical devices industries (remember MediDevi). Some pharmaceutical companies can use quality to better address customer needs, particularly in developing countries, where tampering with authentic products and selling spurious ones continue to harm customers.

• Speed is crucial in this industry because, even in developed countries, too many drugs are sold close to their expiration date. Getting products from the manufacturing site to patients quickly, without holding inventory, could improve the efficacy of products and public health. For example, flu vaccines may be ineffective because companies have to develop vaccines long before anyone knows what strain of the virus will prevail in that season. If pharmaceutical companies could speed up their vaccine creation process and supply chains, they could respond to flu viruses faster, which could save lives. Speed is also important for products that are focused more on prevention, such as vitamins and herbs, and for personalized medications.

Affordability is key to long-term survival in this industry. Look at what happened to Mylan and its EpiPens. The pens cost less than $2 to produce, and Mylan sold them for $57 in 2007. Then, in 2016, it raised the price to $700. The public outcry resulted in congressional hearings and the introduction of generics. But Mylan is not alone. These aggressive pricing practices are all too common, and in the long run they don’t work; customers turn against companies they see as price gougers. This trend will grow, as millennials demand ethical and transparent practices and won’t buy from companies that don’t adopt them.

Apparel Retail

Customer needs in the apparel industry are fit, fabric, fashion, speed, and affordability. This industry has been more affected by millennials than others. Strategies such as service (chapter 3), personalization (chapter 4), and speed (chapter 5), alone or in combination, can help retailers address customer needs, depending on the company’s offering and targeted customer segment. Whatever strategy is being adopted, a company’s offerings need to be affordable or millennials won’t buy them.

• Service is the easiest way to get customers to spend more. Realizing this, many more companies now offer home delivery. Many companies will need to weigh the advantages of brick and mortar versus online stores and look at how to deliver great service in each—or using both. For example, a retailer might offer style advice in its physical store whereas managing orders could take place online, for easy tracking of user information and provision of future recommendations.

• Affordable personalization is a huge opportunity for apparel retailers. If you are selling custom-made clothes, such as suits and shoes, and can do this affordably for customers, you’ll have a huge advantage.

• Speed continues to be important if you are selling a commodity or anything standardized. Long lead times and product unavailability could cost you customers. Finding a way to address your impatient customer needs quickly is critical.

Additionally, the industry needs to stop making returns difficult and alienating customers in other ways, such as by banning those who return too often. And because millennials are socially and environmentally conscious, counting on customers to throw away their old clothes and buy new ones is a doomed strategy. The industry will need to use other strategies to grow demand.

Automotive

Customers are looking for fast, affordable, and safe transportation that doesn’t pollute the environment. Customization (chapter 4), service (chapter 3), and quality (chapter 6), alone or in combination, are all strategies that can deliver on these goals and attract customers.

• Personalization may not be practical in the near future, but automotive companies can customize their offerings by customer segment to make them affordable. For example, city drivers need easy-to-park cars, while rural drivers need good shock absorbers and four-wheel drive. Selling cars with both sets of features will add little value from most customers’ perspective, but it will increase costs. Similarly, cars designed for developing countries need to be affordable and reliable on bad roads, but amenities like sunroofs are probably unnecessary if they add to the car’s cost.

Cars explicitly designed for ride-hailing needs should offer affordability, comfortable rides, easy cleaning, a good music system, and reliability. Amenities like assisted driving or parking or a sunroof may not be of value for ride-hailing customers.

In short, car manufacturers can create products that cater to the different needs of their different segments without increasing costs—if they pay attention to what each segment actually needs.

• Service will become important, as the repeat customer rate is absymal.2 The industry has to figure out how to retain current customers by changing the whole buying experience, servicing cars better, and disposing of them responsibly. Tesla is already experimenting with delivering cars, and even repair personnel, to customers’ doors. But most of the industry is stuck in the 1980s and needs a complete overhaul.

• Quality will remain crucial. Servicing cost and frequent recalls not only add costs but also create customer credibility issues.

The big issue the industry should be focusing on is affordability. New cars are beyond the means of younger people, and older cars are too expensive to maintain.3 Finding ways to reduce both the purchase price and the lifetime cost of vehicles will address customer needs and increase the industry’s longevity.

Consumer Goods

Millennials are looking for healthy natural products. Quality (chapter 6), personalization (chapter 4), and speed (chapter 5) can help the industry become more customer focused.

• Quality of products and ethical sourcing of raw materials will become increasingly important because millennials are so socially and environmentally conscious. Companies will benefit by developing healthy, environmentally friendly products from natural materials. However, because boomers will continue to buy the brands they trust, companies should not be in a hurry to get rid of their current brands. The transition from the old to the new can be made as customer demand changes.

• Companies will benefit from personalization based on customer preferences, preferred ingredients in different geographies, and affordability. A database with customer preferences would undoubtedly help companies personalize their products and address the needs of different segments.

• Speed remains critical when launching new products or meeting changing customer needs. Millennials are impatient and have low brand loyalty. Companies that meet their changing needs quickly will be the winners.

Finally, big companies may benefit by forming alliances with regional companies. For example, if Patanjali products become successful with millennials in the United States, an alliance between Patanjali and a Western multinational could be beneficial to both. Customer-focused strategies have to be tailored for each company based on the segments they support, even for companies within the same industry. For example, strategies that would work for Procter & Gamble may not work for Unilever. Choosing and implementing the right strategy requires careful work.

However, all companies that count on old strategies that don’t work, such as incremental innovation, need to start choosing new strategies based on customer needs. Doing this—and developing operations to support them—will make companies and their products more relevant to customers and will provide long-term investor value, if the new strategies have organizational support. Having a plan for getting an organization to support the new strategy is crucial. Communication alone cannot make it happen, because the strategies discussed here will be such a radical change that they will require a new organizational perspective and many systemic changes.

CHANGING ORGANIZATION PERSPECTIVE

A company is like a large ship—changing direction requires cooperation from everyone, not just the captain. When it comes to implementing new strategies, organizational changes are key, and these require systematic, sequential planning. Here are the main steps.

Step 1: Change Incentives

Most companies use stocks and stock options based on financial performance as the main form of compensation for their leaders. This has to change. Instead, leaders should be rewarded for how well they deliver on customer needs. Investors should encourage the leadership team to think more like long-term owners and less in terms of three- to five-year assignments. Having customer metrics determine CEO and leadership compensation would help, too. These metrics should be diversified to include such things as customer satisfaction ratings, customer retention rates, and growth of the customer base. Surveys performed by third parties and feedback on social media both should be used. Once incentives for leaders have been fixed, it should be rolled out to the rest of the organization.

Step 2: Organize in Customer-Facing Groups

Most companies are organized functionally, into silos such as sales, marketing, manufacturing, and finance. The idea is that these areas are so different that employees should specialize in them. But this thinking is a leftover from the industrial age. Specialization played a more significant role then than it does today. These days, what counts is responding to customer needs in an entrepreneurial way, as companies like Haier have. Their customer-facing organization has radically improved the company’s connection to customer needs, and other companies need to do this too or be left behind.

Customers don’t care whether your employees are from marketing or IT or somewhere in the supply chain. All they care about is how well you meet their needs. Functional silos work against meeting customer needs; employees tend to feel more loyalty to the department or function than to the customers. This is inevitable when employee compensation and promotions are driven by how happy the employees keep their boss. Over time, this leads to leaders and middle managers who are all completely disconnected from customers. When companies try to work around this with a matrix organization (in which employees report to a functional boss and a business boss), the result is usually greater confusion and slower decision-making. Lack of customer focus remains the same. Haier has experimented with customer-facing teams with great success.

To achieve customer focus, create teams organized around customer segments rather than geographic location, type of product, or size. Empower these teams and build support for them into the organization. These customer-facing groups could each consist of people in sales, research and development, marketing, finance, and operations. The exact mix will depend upon the kind of customer the group supports, but each should have responsibility for revenue and profit and loss, along with the flexibility to link to customers’ longer-term priorities. This is more entrepreneurial than most big corporations today are.

Chapter 3 provided detail on creating customer segments, but one warning here: When companies organize around customer segments, many tend to lose focus on operations. This, and the organization’s increasing complexity, can overwhelm an organization. FMP, for example, was organized in customer-facing teams, but their operations and their management of third-party providers didn’t support those teams well. The organizations supporting customer teams must excel in their areas of expertise and act strategically. The objective of the support teams should be to develop leading platforms, manage risk, share knowledge, and provide oversight. To achieve this, support organizations should be encouraged to compete with other providers in the market. They should be allowed to sell their services to other companies or directly to customers.

In short, the entrepreneurial spirit should be encouraged throughout the organization—not just in the customer-facing teams.

Step 3: Develop a Customercentric Culture

It’s fashionable to talk about a company’s culture, and many companies try to create cultures that make them unique among the competition. However, most go about it the wrong way, focusing on things like free food, open offices, parties, employee trips, open presentations by high-level executives, and gyms. None of these things focus employees on customers or encourage attention to detail. Companies that historically have done well and continue to do well, companies like Southwest and Disney, have created and continue to support truly customercentric cultures. They make their mission clear to everyone, as in the following.

• According to Amazon’s jobs website, “When Amazon launched in 1995, it was with the mission ‘to be Earth’s most customer-centric company, where customers can find and discover anything they might want to buy online, and [it] endeavors to offer its customers the lowest possible prices.’”4

• Southwest’s website says, “We like to think of ourselves as a Customer Service company that happens to fly airplanes (on schedule, with personality and perks along the way).”5

• Apple’s employee training manual states, “Your job is to understand all of your customers’ needs—some of which they may not even realize they have.”6

• Disney cast members are taught “The guest isn’t always right, but let them be wrong with dignity.”

These companies don’t just talk the talk, they walk the walk. Their customers know it and love them. Not surprisingly, all are leaders in their industries, both in customer satisfaction and in revenue/profit growth.

As we have seen, attention to detail and continuous improvement are vital parts of these companies’ cultures; you can’t have a truly customer-focused culture without them. Only when every employee is encouraged to improve their work processes and deliver value to customers will you succeed. This means that everyone in the company tries every day not only to improve their own work processes but also to share with others what they’ve learned—including what they learn from customer feedback. Companies that do this continually improve and achieve omotenashi—delighting customers in every way.

Step 4: Focus on Employee Development

Employees are assets, and companies that succeed invest in them. Happy employees lead to better customer interactions. So recruit them carefully, pay them fairly, reward them appropriately, train them well, allow them to make decisions without fear, and let them fail safely.

The recruiting process should focus on hiring employees who are customer oriented. This is particularly true for customer-facing teams. Consider how Southwest does it. In addition to employees’ ability to perform their respective job well—that is, the pilot should be able to fly planes safely—the company also looks for three attributes in a candidate:

• A warrior spirit, or the desire to excel, act with courage, persevere, and innovate.

• A servant’s heart, or the ability to put others first, treat everyone with respect, and proactively serve customers.

• A fun-loving attitude, including passion, joy, and an aversion to taking oneself too seriously.7

Every candidate is rated across these attributes to assess whether they will fit with Southwest’s culture, irrespective of the position for which they are being hired. Even promotions are tied to these traits. People are measured both by results and by how they achieved the results. In a 2014 employee survey, 86% of employees said they were proud to work for Southwest. Carefully defining the traits you need in employees to keep customers happy usually results in happy employees, too.

Once you have hired the right person, the next step is onboarding and training to help them get oriented toward customers. Consider how the Disney resorts does it. A new employee spends a full six weeks in training, during which time they learn that they are not selling a product, they are selling an experience. Only when they have imbibed this do employees even meet guests.

Most customer-focused strategies fail because the organization is not oriented toward customers. Pushing an organization to change its focus through brute force or a leader’s charisma may work for a year or two, but without structural change, directional changes don’t last. The organization goes back to its old ways once the leader leaves. But changes are possible. Disney and Haier show that even large corporations can reinvent themselves—through committed leadership and radical structural change.

SOCIETAL IMPLICATIONS

People think failing businesses do not affect a country’s economy and wealth. They are wrong. Businesses play a critical role in any society’s employment and prosperity. Now we are at an inflection point—the failure of companies to become customer focused can affect not only the companies themselves but also a whole country.

Consider Finland. In the early 2000s, its industries and high standard of living placed this small country among the world’s top twenty nations. Finland doesn’t have oil, but its vast forests and paper exports were big business—and it became a technology hub, too. Nokia contributed 4% to Finland’s gross domestic product in 2000. But then Apple launched the iPhone, and Nokia failed. Its phones didn’t address customer needs for internet connectivity on the go. Then the iPad lowered paper consumption as more and more customers read news and magazines on tablets. Since the 2008 recession, Finland’s economy has lagged behind that of the United States and all the EU countries except Italy.8

Other countries are in the same situation. Solar energy will eventually disrupt oil- and gas-producing countries. Venezuela’s economy is already reeling due to a drop in oil prices. When the consumption of carbon-based fuels drops, as it probably will within a few years, Middle Eastern countries’ economies will drop with them. So will the economies of Russia, Norway, the United Kingdom, and Denmark, unless they find other growth drivers for their economies.

The U.S. economy will be disrupted, too, unless corporations make radical changes. American corporations are so disconnected from their customers that they are losing to upstarts in all parts of the world, and at home, too. The largest companies, like Walmart, ExxonMobil, GE, AT&T, and even Apple, are not growing their revenues and profits organically. Most Americans assume that disrupters will be another American company, so that, at a national level, the money and jobs will flow from one set of companies to another. They point to U.S. leadership in technology and innovation and say that American corporations will continue to succeed.

This confidence is frightening and is not justified by reality. American car companies lost to Japanese car companies in the 1980s because of their failure to deliver the quality that customers wanted, not because American companies were not innovating. Today, competitors are coming from all parts of the world. Chinese and Indian companies are connecting better with customer needs and will eventually surpass their American counterparts. In household appliances, smartphones, solar energy, and mobile payments, Chinese companies are already beating their American counterparts.

There is a dire need for American companies to make radical changes, not just for their own growth and survival but also for the health of the American economy. Otherwise, the prosperity the United States has enjoyed for so long will end. The money and talent will go to other countries—countries whose companies create value for their customers. Darwin’s laws of natural selection are as valid in the global economy as they are in the animal kingdom. The key to survival in this era of changing global customer needs is to focus on those needs and then adapt—faster and better than the competition. It’s not too late for U.S. companies, but they must change their focus and adopt new strategies—now.