Chapter 10. Hyperparameter Tuning and Automated Machine Learning

In the previous chapters, we have seen how Kubeflow helps with the various phases of machine learning. But knowing what to do in each phase—whether it’s feature preparation or training or deploying models—require some amount of expert knowledge and experimentation. According to the “no free lunch” theorem,1 no single model works best for every machine learning problem, therefore each model must be constructed carefully. It can be very time-consuming and expensive to fully build a highly performing model if each phase requires significant human input.

Naturally, one might wonder: is it possible to automate parts—or even the entirety—of the machine learning process? Can we reduce the amount of overhead for data scientists while still sustaining high model quality?

In machine learning, the umbrella term for solving these type of problems is automated machine learning (or “AutoML” for short). It is a constantly evolving field of research, and has found its way to the industry with practical applications. AutoML seeks to simplify machine learning for experts and non-experts alike by reducing the need for manual interaction in the more time-consuming and iterative phases of machine learning: feature engineering, model construction, and hyperparameter configuration.

In this chapter we will see how Kubeflow can be used to automate hyperparameter search and neural architecture search, two important subfields of AutoML.

Automated Machine Learning: An Overview

Automated machine learning (AutoML) is an umbrella-term for the various processes and tools that automates parts of the machine learning process. On a high level, AutoML refers to any algorithms and methodologies that seek to solve one or more of the following problems:

- Data preprocessing

-

Machine learning requires data, and raw data can come from various sources and in different formats. To make raw data useful, human experts typically have to comb over the data, normalize values, remove erroneous or corrupted data, and ensure data consistency.

- Feature engineering

-

Training models with too few input variables (or “features”) can lead to inaccurate models. However, too many features can also be problematic - the learning process would slower and more resource-consuming, and overfitting problems can occur. Coming up with the right set of features can be the most time-consuming part of building a machine learning model. Automated feature engineering can speed up the process of feature extraction, selection, and transformation.

- Model selection

-

Once you have all the training data, you need to pick the right training model for your dataset. The ideal model should be as simple as possible while still providing a good measure of prediction accuracy.

- Hyperparameter tuning

-

Most learning models have a number of parameters that are external to the model, such as the learning rate, batch size, and the number of layers in the neural network. We call these “hyperparameters” to distinguish them from model parameters that are adjusted by the learning process. Hyperparameter tuning is the process of automating the search process for these parameters, in order to improve the accuracy of the model.

- Neural architecture search

-

A related field to hyperparameter tuning is neural architecture search (NAS). Instead of choosing between a fixed range of values for each hyperparameter value, NAS seeks to take automation one step further and generate an entire neural network that outperforms hand-crafted architectures. Common methodologies for NAS include reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms.

The focus of this chapter will be on the latter two problems—hyperparameter tuning and neural architecture search. These two fields are closely related and can be solved using similar methodologies.

Hyperparameter Tuning with Kubeflow Katib

In Chapter 7, it was mentioned that we needed to set a few hyperparameters. In machine learning, hyperparameters refer to parameters that are set before the training process begins (as opposed to model parameters which are learned from the training process). Examples of hyperparameters include the learning rate, number of decision trees, number of layers in a neural network, etc.

The concept of hyperparameter optimization is very simple: select the set of hyperparameter values that lead to optimal model performance. A hyperparameter tuning framework is a tool that does exactly that. Typically, the user of such a tool would define a few things:

-

The list of hyperparameters and their valid range of values (called the “search space”)

-

The metrics used to measure model performance

-

The methodology to use for the searching process

Kubeflow comes packaged with Katib 2, a general framework for hyperparameter tuning. Among similar open-source tools, Katib has a few distinguishing features:

- Kubernetes-native

-

This means that Katib experiments can be ported wherever Kubernetes runs.

- Multi-framework support

-

Katib supports many popular learning frameworks, with first-class support for TensorFlow and PyTorch distributed training.

- Language agnostic

-

Training code can be written in any language, as long as it is built as a Docker image.

Note

The name “katib”, meaning a secretary or scribe in Arabic, is an homage to the Vizier framework that inspired its initial version (“vizier” being Arabic for a minister or high official).

In this chapter, we’ll take a look at how Katib simplifies hyperparameter optimization.

Katib Concepts

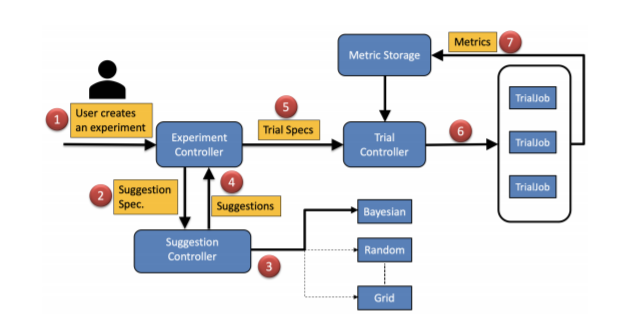

Let’s begin by defining a few terms that are central to the workflow of Katib (as illustrated in Figure 10-1):

- Experiment

-

An experiment is an end-to-end process that takes a problem (e.g., tuning a training model for handwriting recognition), an objective metric (maximize the prediction accuracy), and a search space (range for hyperparameters), and produces a final set of optimal hyperparameter values.

- Suggestion

-

A suggestion is one possible solution to the problem we are trying to solve. Since we are trying to find the combination of hyperparameter values that lead to optimal model performance, a suggestion would be one set of hyperparameter values from the specified search space.

- Trial

-

A trial is one iteration of the experiment. Each trial takes a suggestion and executes a worker process (packaged through Docker) that produces evaluation metrics. Katib’s controller then computes the next suggestion based on previous metrics and spawns new trials.

Figure 10-1. Katib system workflow (https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.02085.pdf)

Note

In Katib, experiments, suggestions, and trials are all custom resources. This means they are stored in Kubernetes etcd and can be manipulated using standard Kubernetes APIs.

Another important aspect of hyperparameter tuning is how to find the next set of parameters. As of the time of this writing, Katib supports the following search algorithms:

- Grid search

-

Also known as a parameter sweep, Grid Search is the simplest approach—exhaustively search through possible parameter values in the specified search space. Although resource-intensive, Grid Search has the advantage of having high parallelism since the tasks are completely independent.

- Random search

-

Similar to grid search, the tasks in random search are completely independent. Instead of enumerating every possible value, random search attempts to generate parameter values through random selection. When there are many hyperparameters to tune (but only a few have significant impact on model performance), random search can vastly outperform Grid Search. Random search can be useful when the number of discrete parameters is high, which makes grid search infeasible.

- Bayesian optimization

-

This is a powerful approach that uses probability and statistics to seek better parameters. Bayesian optimization builds a probabilistic model for the objective function, finds parameter values that perform well on the model, then iteratively updates the model based on metrics collected during trial runs. Intuitively speaking, Bayesian optimization seeks to improve upon a model by making informed guesses. This optimization method relies on previous iterations to find new parameters, and can be parallelized. While trials are not as independent as grid or random search, Bayesian optimization can find results with less trials overall.

- Hyperband

-

This is a relative new approach that selects configuration values randomly. But unlike traditional random search, Hyperband only evaluates each trial for a small number of iterations. Then it takes the best performing configurations and runs them longer, repeating this process until a desired result is reached. Due to its similarity to random search, tasks can be highly parallelized.

- Other experimental algorithms

-

Such as Tree of Parzen Estimators (TPE) and Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES), both implemented by using the Goptuna optimization framework.

One final piece of the puzzle in Katib is the metrics collector. This is the process that collects and parses evaluation metrics after each trial and pushes them into the persistent database. Katib implements metrics collection through a sidecar container, which runs alongside the main container in a pod.

Overall, Katib’s design makes it highly scalable, portable, and extensible. Since it is part of the Kubeflow platform, Katib natively supports integration with many of Kubeflow’s other training components, like the TFJob and PyTorch operators. Katib is also the first hyperparameter tuning framework that supports multitenancy, making it ideal for a cloud hosted environment.

Installing Katib

Katib is installed by default. To install Katib as a standalone service, you can use the following script in the GitHub repo:

git clone https://github.com/kubeflow/katib bash ./katib/scripts/v1beta1/deploy.sh

If your Kubernetes cluster doesn’t support dynamic volume provisioning, you would also create a persistent volume:

pv_path=https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubeflow/katib/master/manifests/v1beta1/pv/pv.yaml kubectl apply -f pv_path

After installing Katib components, you can navigate to the Katib dashboard to verify that it is running. If you installed Katib through Kubeflow and have an endpoint, simply navigate to the Kubeflow dashboard and select “Katib” in the menu. Otherwise, you can set up port forwarding to test your deployment:

kubectl port-forward svc/katib-ui -n kubeflow 8080:80

Then navigate to:

http://localhost:8080/katib/

Running Your First Katib Experiment

Now that Katib is up and running in your cluster, let’s take a look at how to run an actual experiment. In this section we will use Katib to tune a simple MNist model. You can find the source code and all configuration files on Katib’s GitHub page here: https://github.com/kubeflow/katib/tree/master/examples/v1beta1/mxnet-mnist.

Prepping Your Training Code

The first step is to prepare your training code. Since Katib runs training jobs for trial evaluation, each training job needs to be packaged as a Docker container. Katib is language-agnostic, so it does not matter how you write the training code. However, to be compatible with Katib, the training code must satisfy a couple of requirements:

-

Hyperparameters must be exposed as command-line arguments, for example:

python mnist.py --batch_size=100 --learning_rate=0.1

-

Metrics must be exposed in a format consistent with the metrics collector. Katib currently supports metrics collection through standard output, file, TensorFlow events, or custom. The simplest option is to use the standard metrics collector, which means the evaluation metrics must be written to stdout, in the format

metrics_name=metrics_value

The example training model code that we will use can be found on this GitHub site.

After preparing the training code, simply package it as a Docker image and it is ready to go.

Configuring an experiment

Once you have the training container, the next step is to write a spec for your experiment. Katib uses Kubernetes custom resources to represent experiments. The example that follows can be downloaded from this GitHub site:

Example 10-1. Example experiment spec

apiVersion: "kubeflow.org/v1beta1"

kind: Experiment

metadata:

namespace: kubeflow

labels:

controller-tools.k8s.io: "1.0"

name: random-example

spec:

objective:  type: maximize

goal: 0.99

objectiveMetricName: Validation-accuracy

additionalMetricNames:

- Train-accuracy

algorithm:

type: maximize

goal: 0.99

objectiveMetricName: Validation-accuracy

additionalMetricNames:

- Train-accuracy

algorithm:  algorithmName: random

parallelTrialCount: 3

algorithmName: random

parallelTrialCount: 3  maxTrialCount: 12

maxFailedTrialCount: 3

parameters:

maxTrialCount: 12

maxFailedTrialCount: 3

parameters:  - name: --lr

parameterType: double

feasibleSpace:

min: "0.01"

max: "0.03"

- name: --num-layers

parameterType: int

feasibleSpace:

min: "2"

max: "5"

- name: --optimizer

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- sgd

- adam

- ftrl

trialTemplate:

- name: --lr

parameterType: double

feasibleSpace:

min: "0.01"

max: "0.03"

- name: --num-layers

parameterType: int

feasibleSpace:

min: "2"

max: "5"

- name: --optimizer

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- sgd

- adam

- ftrl

trialTemplate:  goTemplate:

rawTemplate: |-

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{.Trial}}

namespace: {{.NameSpace}}

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: {{.Trial}}

image: docker.io/kubeflowkatib/mxnet-mnist

command:

- "python3"

- "/opt/mxnet-mnist/mnist.py"

- "--batch-size=64"

{{- with .HyperParameters}}

{{- range .}}

- "{{.Name}}={{.Value}}"

{{- end}}

{{- end}}

restartPolicy: Never

goTemplate:

rawTemplate: |-

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{.Trial}}

namespace: {{.NameSpace}}

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: {{.Trial}}

image: docker.io/kubeflowkatib/mxnet-mnist

command:

- "python3"

- "/opt/mxnet-mnist/mnist.py"

- "--batch-size=64"

{{- with .HyperParameters}}

{{- range .}}

- "{{.Name}}={{.Value}}"

{{- end}}

{{- end}}

restartPolicy: Never

That’s quite a lot to follow. Let’s take a closer look at each part of the spec section:

Objective. This is where you configure how to measure the performance of your training model, and the goal of the experiment. In this experiment, we are trying to maximize the validation-accuracy metric. We are stopping our experiment if we reach the objective goal of 0.99 (99% accuracy). The

additionalMetricsNamesrepresents metrics that are collected from each trial, but not used to evaluate the trial.

Algorithm. In this experiment we are using random search; some algorithms may require additional configurations.

Budget configurations. This is where we configure our experiment budget. In this experiment, we would run 3 trials in parallel, with a total number of 12 trials. We would also stop our experiment if we have 3 failed trials. This last part is also called an error budget—an important concept in maintaining production-grade system uptime.

Parameters. Here we define which parameters we want to tune, and the search space for each. For example, the

learning rateparameter is exposed in the training code as--lr. It is a double, with a contiguous search space between 0.01 and 0.03.

Trial template. The last part of the experiment spec is the template from which each trial is configured. For the purpose of this example, the only important parts are:

image: docker.io/kubeflowkatib/mxnet-mnist

command:

- "python3"

- "/opt/mxnet-mnist/mnist.py"

- "--batch-size=64"

This should point to the Docker image that you built in the previous step, with the command line entrypoint to run the code.

Running the Experiment

After everything is configured, apply the resource to start the experiment:

kubectl apply -f random-example.yaml

You can check the status of the experiment by running the following:

kubectl -n kubeflow describe experiment random-example

In the output, you should see something like:

Example 10-2. Example experiment output

Name: random-example

Namespace: kubeflow

Labels: controller-tools.k8s.io=1.0

Annotations: <none>

API Version: kubeflow.org/v1beta1

Kind: Experiment

Metadata:

Creation Timestamp: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Finalizers:

update-prometheus-metrics

Generation: 2

Resource Version: 720692

Self Link: /apis/kubeflow.org/v1beta1/namespaces/kubeflow/experiments/random-example

UID: dc6bc15a-250d-11ea-8cae-42010a80010f

Spec:

Algorithm:

Algorithm Name: random

Algorithm Settings: <nil>

Max Failed Trial Count: 3

Max Trial Count: 12

Metrics Collector Spec:

Collector:

Kind: StdOut

Objective:

Additional Metric Names:

accuracy

Goal: 0.99

Objective Metric Name: Validation-accuracy

Type: maximize

Parallel Trial Count: 3

Parameters:

Feasible Space:

Max: 0.03

Min: 0.01

Name: --lr

Parameter Type: double

Feasible Space:

Max: 5

Min: 2

Name: --num-layers

Parameter Type: int

Feasible Space:

List:

sgd

adam

ftrl

Name: --optimizer

Parameter Type: categorical

Trial Template:

Go Template:

Raw Template: apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{.Trial}}

namespace: {{.NameSpace}}

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: {{.Trial}}

image: docker.io/kubeflowkatib/mxnet-mnist-example

command:

- "python"

- "/mxnet/example/image-classification/train_mnist.py"

- "--batch-size=64"

{{- with .HyperParameters}}

{{- range .}}

- "{{.Name}}={{.Value}}"

{{- end}}

{{- end}}

restartPolicy: Never

Status:  Conditions:

Last Transition Time: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Last Update Time: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Message: Experiment is created

Reason: ExperimentCreated

Status: True

Type: Created

Last Transition Time: 2019-12-22T22:55:10Z

Last Update Time: 2019-12-22T22:55:10Z

Message: Experiment is running

Reason: ExperimentRunning

Status: True

Type: Running

Current Optimal Trial:

Conditions:

Last Transition Time: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Last Update Time: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Message: Experiment is created

Reason: ExperimentCreated

Status: True

Type: Created

Last Transition Time: 2019-12-22T22:55:10Z

Last Update Time: 2019-12-22T22:55:10Z

Message: Experiment is running

Reason: ExperimentRunning

Status: True

Type: Running

Current Optimal Trial:  Observation:

Metrics:

Name: Validation-accuracy

Value: 0.981091

Parameter Assignments:

Name: --lr

Value: 0.025139701133432946

Name: --num-layers

Value: 4

Name: --optimizer

Value: sgd

Start Time: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Trials: 12

Observation:

Metrics:

Name: Validation-accuracy

Value: 0.981091

Parameter Assignments:

Name: --lr

Value: 0.025139701133432946

Name: --num-layers

Value: 4

Name: --optimizer

Value: sgd

Start Time: 2019-12-22T22:53:25Z

Trials: 12  Trials Running: 2

Trials Succeeded: 10

Events: <none>

Trials Running: 2

Trials Succeeded: 10

Events: <none>

Some of the interesting parts of the output are:

Status: Here you can see the current state of the experiment, as well as its previous states.

Current Optimal Trial: This is the “best” trial so far, i.e., the trial that produced the best outcome as determined by our predefined metrics. You can also see this trial’s parameters and metrics.

Trials Succeeded/Running/Failed: Here you can see how your experiment is progressing.

Katib User Interface

Alternatively, you can use Katib’s user interface to submit and monitor your experiments. If you have a Kubeflow deployment, you can navigate to the Katib UI by clicking on “Katib” in the navigation panel and then “Hyperparameter Tuning” on the following screen (see Figure 10-2).

Figure 10-2. Katib UI main page

Let’s submit our random search experiment here (see Figure 10-3). You can simply paste a YAML in the textbox here, or have one generated for you by following the UI. To do this, click on the Parameters tab.

Figure 10-3. Configuring a new experiment, part 1

You should see a panel like Figure 10-4. Enter the necessary configuration parameters on this page—define a run budget and the validation metrics.

Figure 10-4. Configuring a new experiment, part 2

Then scroll down the page and finish up the rest of the experiment, by configuring the search space and the trial template. For the latter, you can just leave it on the default template. When you are done, click “Deploy.”

Now that the experiment is running, you can monitor its status and see a visual graph of the progress (see Figure 10-5). You can see your running and completed experiments by navigating to the drop-down menu in the Katib dashboard, and then selecting “UI” and then “Monitor.”

Figure 10-5. Katib UI for an experiment

Below this graph (Figure 10-6), you can see a detailed breakdown of each trial, the values of the hyperparameters for each trial, and the final metric values. This is very useful for comparing the effects of certain hyperparameters on the model performance.

Figure 10-6. Katib metrics for an experiment

Since we are also collecting validation metrics along the way, we can actually plot the graph for each trial. Click a row to see how the model performs with the given hyperparameter values across time (Figure 10-7):

Figure 10-7. Metrics for each trial

Tuning Distributed Training Jobs

In Chapter 7 we have seen an example of using Kubeflow to orchestrate distributed training. What if we want to use Katib to tune parameters for a distributed training job?

The good news is that Katib natively supports integration with TensorFlow and PyTorch distributed training. A MNist example with TensorFlow can be found from Katib’s GitHub page. This example uses the same MNist distributed training example we’ve seen in Chapter 7, and directly integrates it into the Katib framework. In the example, we will launch an experiment to tune hyperparameters (learning rate and batch size) for a distributed TensorFlow job.

Example 10-3. Distributed training example

apiVersion: "kubeflow.org/v1beta1" kind: Experiment metadata: namespace: kubeflow name: tfjob-example spec: parallelTrialCount: 3maxTrialCount: 12 maxFailedTrialCount: 3 objective:

type: maximize goal: 0.99 objectiveMetricName: accuracy_1 algorithm: algorithmName: random metricsCollectorSpec:

source: fileSystemPath: path: /train kind: Directory collector: kind: TensorFlowEvent parameters:

- name: learning_rate parameterType: double feasibleSpace: min: "0.01" max: "0.05" - name: batch_size parameterType: int feasibleSpace: min: "100" max: "200" trialTemplate: trialParameters: - name: learningRate description: Learning rate for the training model reference: learning_rate - name: batchSize description: Batch Size reference: batch_size trialSpec: apiVersion: "kubeflow.org/v1" kind: TFJob spec: tfReplicaSpecs:

Worker: replicas: 2 restartPolicy: OnFailure template: spec: containers: - name: tensorflow image: gcr.io/kubeflow-ci/tf-mnist-with-summaries:1.0 imagePullPolicy: Always command: - "python" - "/var/tf_mnist/mnist_with_summaries.py" - "--log_dir=/train/metrics" - "--learning_rate=${trialParameters.learningRate}" - "--batch_size=${trialParameters.batchSize}"

The total and parallel trial counts are similar to the previous experiment. In this case they refer to the total and parallel number of distributed training jobs to run.

The objective specification is also similar—in this case we want to maximize the

accuracymeasurement.

The metrics collector specification looks slightly different. This is because this is a TensorFlow job, and we can use TFEvents outputted by TensorFlow directly. Using the built-in

TensorFlowEventcollector type, Katib can automatically parse TensorFlow events and populate the metrics database.

The parameter configurations are exactly the same—in this case we are tuning the learning rate and batch size of the model.

The trial template should look familiar to you if you are familiar with Chapter 7—it’s the same distributed training example spec that we ran before. The imporant difference here is that we’ve parameterized the input to

learning_rateandbatch_size.

So now you have learned how to use Katib to tune hyperparameters. But notice that you still have to select the model yourself. Can we reduce the amount of human work even further? What about other subfields in AutoML? In the next section we will look at how Katib supports the generation of entire artificial neural networks.

Neural architecture search

Neural architecture search (NAS) is a growing sub-field in automated machine learning. Unlike hyperparameter tuning, where the model is already chosen and our goal is the optimize its performance by turning a few knobs, in NAS we are trying to generate the network architecture itself. Recent research has shown that NAS can outperform handcrafted neural networks on tasks like image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation.3

Most the methodologies for NAS can be categorized as either generation methods or mutation methods. In generation methods, the algorithm will propose one or more candidate architectures in each iteration. These proposed architectures are then evaluated and then refined in the next iteration. In mutation methods, an overly-complex architecture is proposed first, and subsequent iterations will attempt to prune the model.

Katib currently supports two implementations of NAS: “Differentiable Architecture Search (DARTS),”4, and “Efficient Neural Architecture Search (ENAS).”5 DARTS achieves scalability of NAS by relaxing the search space to be continuous instead of discrete, and utilizes gradient descent to optimize the architecture. ENAS takes a different approach, by observing that in most NAS algorithms the bottleneck occurs during the training of each child model. ENAS forces each child model to share parameters, thus improving the overall efficiency.

The general workflow of NAS in Katib is similar to hyperparameter search, with an additional step for constructing the model architecture. An internal module of Katib, called the Model Manager, is responsible for taking topological configurations and mutation parameters, and constructing new models. Katib then uses the same concepts of trials and metrics to evaluate the model’s performance.

As an example, this is the spec of a NAS experiment using DARTS:

Example 10-4. Example NAS experiment spec

apiVersion: "kubeflow.org/v1beta1"

kind: Experiment

metadata:

namespace: kubeflow

name: darts-example-gpu

spec:

parallelTrialCount: 1

maxTrialCount: 1

maxFailedTrialCount: 1

objective:

type: maximize

objectiveMetricName: Best-Genotype

metricsCollectorSpec:

collector:

kind: StdOut

source:

filter:

metricsFormat:

- "([\w-]+)=(Genotype.*)"

algorithm:

algorithmName: darts

algorithmSettings:

- name: num_epochs

value: "3"

nasConfig:  graphConfig:

numLayers: 3

operations:

- operationType: separable_convolution

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- operationType: dilated_convolution

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- "5"

- operationType: avg_pooling

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- operationType: max_pooling

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- operationType: skip_connection

trialTemplate:

trialParameters:

- name: algorithmSettings

description: Algorithm settings of DARTS Experiment

reference: algorithm-settings

- name: searchSpace

description: Search Space of DARTS Experiment

reference: search-space

- name: numberLayers

description: Number of Neural Network layers

reference: num-layers

trialSpec:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: training-container

image: docker.io/kubeflowkatib/darts-cnn-cifar10

imagePullPolicy: Always

command:

- python3

- run_trial.py

- --algorithm-settings="${trialParameters.algorithmSettings}"

- --search-space="${trialParameters.searchSpace}"

- --num-layers="${trialParameters.numberLayers}"

resources:

limits:

nvidia.com/gpu: 1

restartPolicy: Never

graphConfig:

numLayers: 3

operations:

- operationType: separable_convolution

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- operationType: dilated_convolution

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- "5"

- operationType: avg_pooling

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- operationType: max_pooling

parameters:

- name: filter_size

parameterType: categorical

feasibleSpace:

list:

- "3"

- operationType: skip_connection

trialTemplate:

trialParameters:

- name: algorithmSettings

description: Algorithm settings of DARTS Experiment

reference: algorithm-settings

- name: searchSpace

description: Search Space of DARTS Experiment

reference: search-space

- name: numberLayers

description: Number of Neural Network layers

reference: num-layers

trialSpec:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: training-container

image: docker.io/kubeflowkatib/darts-cnn-cifar10

imagePullPolicy: Always

command:

- python3

- run_trial.py

- --algorithm-settings="${trialParameters.algorithmSettings}"

- --search-space="${trialParameters.searchSpace}"

- --num-layers="${trialParameters.numberLayers}"

resources:

limits:

nvidia.com/gpu: 1

restartPolicy: Never

The general structure of a NAS experiment is similar to that of a hyperparameter search experiment; the majority of the spec should look very familiar: the most important difference is the addition of the

nasConfig. This is where you configure the specifications of the neural network that you want to create, such as the number of layers, the inputs and outputs at each layer, and the types of operations.

Advantages of Katib Over Other Frameworks

There are many similar open-source systems for hyperparameter search, among them are NNI, Optuna, Ray Tune, and HyperOpt. In addition, the original design of Katib was inspired by Google Vizier. These frameworks offer many capabilities similar to Katib, namely the ability to configure parallel hyperparameter sweeps using a variety of algorithms, there are a few features of Katib that makes it unique:

- Design catering to both user and admin.

-

Most tuning frameworks are designed to cater to the user - the data scientist performing the tuning experiment. Katib is also designed to make life easier for the system admin, who is responsible for maintaining the infrastructure, allocating compute resources, and monitoring system health.

- Cloud native design

-

Other frameworks (such as Ray Tune) may support integration with Kubernetes, but often requires additional effort to set up a cluster. By contrast, Katib is the first hyperparameter search framework to base its design entirely on Kubernetes - every one of its resources can be accessed and manipulated by Kubernetes APIs.

- Scalable and portable

-

Because Katib uses Kubernetes as its orchestration engine, it is very easy to scale up an experiment. You can run the same experiments on a laptop for prototyping and deploy the job to a production cluster with minimal changes to the spec. By contrast, other frameworks require additional effort to install and configure depending on the hardware availability.

- Extensible

-

Katib offers flexible and pluggable interfaces for its search algorithms and storage systems. Most other frameworks come with a preset list of algorithms and have hardcoded mechanisms for metrics collection. In Katib, the user can easily implement a custom search algorithm and integrate it with the framework.

- Native support

-

For advanced features like distributed training and neural archiecture search.

Conclusion

In this chapter we’ve taken a quick overview of automated machine learning (AutoML), and learned how it can accelerate the development of machine learning models by automating time-consuming tasks like hyperparameter search. With techniques like automated hyperparameter tuning, you can scale up the development of your models while sustaining high model quality.

We’ve then used Katib—a Kubernetes-native tuning service from the Kubeflow platform, to configure and execute a hyperparameter search experiment. We’ve also shown how you can use Katib’s dashboard to submit, track, and visualize your experiments.

We’ve also explored how Katib handles Neural Architecture Search (NAS). Katib currently supports two methods of NAS—DARTS and ENAS, with more development to follow.

Hopefully this has given you some insights into how Katib can be leveraged to reduce the amount of work in your machine learning workflows. Katib is still an evolving project, and you can follow the latest developments on Katib’s GitHub page.

Thank you for joining us on your adventures in learning Kubeflow. We hope that Kubeflow meets your needs and helps you delivery on the promise of machine learning value to your organization. To keep up to date on the latest changes with Kubeflow we encourage you to subscribe to join the Kubeflow Slack and mailing lists.

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_free_lunch_theorem

2 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.02085.pdf

3 T. Elsken, J. H. Metzen, F. Hutter, “Neural Architecture Search: A Survey,” Journal of Machine Learning Research 20 (2019), https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.05377, pp. 1-21.

4 H. Liu, K. Simonyan, and Y. Tang, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1806.09055.pdf.

5 H. Pham et al., “Efficient Neural Architecture Search via Parameter Sharing,” https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.03268.pdf.