Accounting Information Systems and how to prepare for Digital Transformation

Introduction

The recent appearance of the term “Digital Transformation” has fundamentally impacted the discourse on business practices (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Majchrzak et al., 2016). Popular perception defines Digital Transformation as an endeavour of integrating and exploiting new digital technologies, bringing about changes to a firm’s business model, product/service offerings, and business processes (Mathrani et al., 2013; Hess et al., 2016). Among the various changes that might appear, including technology use and modifications to organizational structures and processes, changes to the value creation model and its related financial tenets are particularly imminent (Hess et al., 2016). In this way, Digital Transformation provides the impetus to reconsider the very nature of AIS in their purpose to manage data and information to be used by decision-makers in accounting and finance functions, and to contribute to strategy implementation and internal control of the enterprise.

Today, with an increasingly digital foundation to organizing business operations, “the traditionally presumed sequential and linear links among corporate strategy, firm structure and information systems design are no longer in play” (Bhimani and Willcocks, 2014, p. 469). This insight is exacerbated by new opportunities for data use and analytics that new technologies bring about (see e.g., Anaya et al., 2015). The potential impacts on the accounting and finance functions are numerous: Cost structures will need to become adaptive to more agile data analysis techniques across structured and unstructured data; internal control and documentation will benefit from new analysis techniques; and the distance between analysis and execution by managers will be shortened or even eliminated. In consequence, an accountant’s role will become more focused on redesigning and adapting a “fluid” system of performance metrics, as well as responsibility, incentive and reward structures (Bhimani and Willcocks, 2014, p. 480).

As part of a Digital Transformation, managing business processes will take on a new relevance for designing and managing AIS with a perspective on implementing and controlling business strategy and operations. Cloud computing for instance, as a digital enabler for business, has become a means to experiment with new business processes, while monitoring involved risk factors and maintaining the opportunity to discard unsatisfactory process variants (Bhimani and Willcocks, 2014, p. 484). Such novel process design options bring about a new potential for achieving innovativeness at an operational level while keeping an eye on accounting and finance functions.

Business Processes Management (BPM) has developed over the past decades as a management approach that helps establish a comprehensive view of an enterprise’s operations, defining key performance indicators (KPIs) for measuring and monitoring process performance, and implementing means for continuous process improvement and innovation (vom Brocke et al., 2016). BPM also has its place in the field of AIS, contributing to the basics of AIS design and implementation (see e.g., Hall 2011). However, the contemporary perspective on BPM is mainly focused on relatively stable processes with a consistent and well-defined information systems’ (IS) support. Related process and IS life cycles are considered to be long term. It has only been recent that research on BPM starts to acknowledge the multiple and changing contexts in which BPM operates, calling for a contextual view of BPM and taking into account situational factors related to goal, process, organization, and environment dimensions (vom Brocke et al., 2016). As part of a Digital Transformation, these dimensions might change more flexibly, which makes it necessary to make the design of AIS and its management adaptive to the particular characteristics of the enterprise processes’ context (see Table 6.1). It also requires having a look at the enterprise’s business environment, e.g., with regards to outsourcing (Christ et al., 2015). Repeatedly achieving fit between (a) the business environment and business processes, as well as between (b) business processes and technology will become increasingly prominent despite posing a constant challenge (Trkman, 2010).

In this context, approaching the design of AIS and their management requires a shift in perspectives – one that (a) is focused on enabling technical functions that allow for a (compliant) implementation of AIS and other enterprise systems, and (b) considers AIS-enabled accounting and finance functions and activities as constraints in the design and implementation of enterprise systems in general. In other words, just like for any other set of business processes, the potential for digitalization as part of the accounting and finance functions and activities needs to be re-evaluated. Doing so provides for a novel perspective on AIS in the enterprise because the “manifestation” of AIS, as we have experienced in the past, for instance in form of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems or other dedicated financial and management reporting IS, might eventually dissolve due to blurring system boundaries. Organizational resources might regain a more important role than IT resources (see e.g., Hsu, 2013) in this respect. Further, the distance between temporary technical implementation within temporary business processes on the one side, and the firm’s presumably relatively stable organizational culture and boundary conditions for defining business functions on the other side, increases. This is an observation not uncommon in the contemporary IS literature (see e.g., Besson and Rowe, 2012). It implies that “IS managers … must apply new skills … and new leadership modes which challenge the IS department and require profound adaptation” (Besson and Rowe, 2012, p. 117). It also implies that accountants might need to re-focus on maintaining an efficient and effective operating model for guiding the implementation of control decisions that are, to some extent, implementation-agnostic. This chapter will therefore concentrate on guidelines for implementing Accounting Procedure Documentation (APD) as a vehicle to conceptually integrate AIS, BPM, IT Management and future business planning. A practice-oriented view is provided on how to approach BPM for AIS in the context of Digital Transformation when considering the new legal regulations on AIS in Germany.

Table 6.1 Contextual factors of the BPM context and potential changes through Digital Transformation

Dimension |

Factors |

Potential changes induced by Digital Transformation |

Goal |

Focus |

The distinction between processes for exploitation (improvement, compliance) and exploration (innovation) might dissolve, and more flexible, prudent experimentation becomes necessary. |

Process |

Value contribution, Repetitiveness, Knowledge-intensity, Creativity, Interdependence, Variability |

Core, management and support processes might become more closely interrelated and their variability increases, e.g., through linkages to external business partners. Knowledge intensity rises because automation is extended, repetitiveness reduced, and focus is directed towards more creative (effective, agile) process design. |

Organization |

Scope, Industry, Size, Culture, Resources |

Inter-organizational processes become a necessity, and service-based business aspects gradually replace product-oriented data management. Business processes include partners of different sizes (start-ups, small, medium and large firms). |

Environment |

Competitiveness, Uncertainty |

Due to alternative digital strategies of competitors and business partners, uncertainty in process design as well as risk-taking mentality increase. Measuring performance in relation to competition becomes more difficult. |

Source: Adapted from vom Brocke, Zelt and Schmiedel, 2016

Dealing with digital business objects in AIS

Information management and AIS

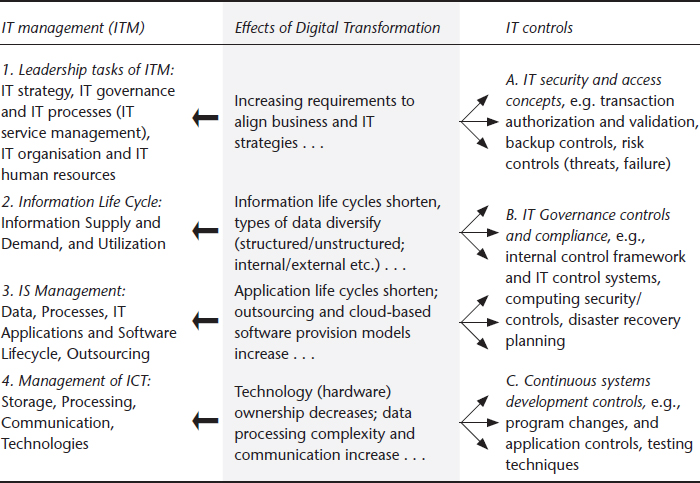

The underlying tenet of Digital Transformation is that all business operations and transactions will increasingly become digitized. While this trend towards digital business objects is not new, its interpretation in today’s business context may be. It might lead to a more streamlined execution of related digital processes, objects and representations, as well as information and IT management in general. From an IT management (ITM) perspective, AIS-specific management functions and activities can be positioned diagonally to other enterprises’ ITM activities (see Table 6.2). Combining two popular models (Krcmar, 2005; Hall, 2011) show that particular requirements emerge in the Digital Transformation context as the result of three major areas of IT controls (A, B, C in Table 6.2) relating to anticipated changes and four major areas of ITM (1 to 4 in Table 6.2). Together they lead to a set of complex management tasks.

As part of Digital Transformation, specific problematic aspects appear for designing and implementing internal controls that require further discussion, and that potentially include various systems apart from AIS. Such aspects include:1

• Retaining compliance with higher velocity of system changes and shortened IT application lifecycles;

• Achieving and retaining compliance to requirements for documenting of business transactions, storage and record keeping in distributed IS and across various IS;

• Implementing guidelines on data accessibility and preservation set by external public authorities (according to domestic legislation);

• Digitization of paper-based documents and future accessibility of electronic records.

Focusing on internal controls, the expected increased volatility of IS suggests reconsidering how digital business objects are managed and handled throughout the various systems involved in finance and accounting functions and activities. To this end, various basic principles exist that help in designing internal controls; these principles however are challenged by Digital Transformation, as outlined in Table 6.3.

Table 6.2 Diagonal positioning of IT controls against general IT management functions

In order to cope with these outlined aspects and anticipated challenges, an analysis and, eventually, revision of AIS – or respectively, the accounting and finance functions and activities – on the process level becomes a prerequisite. Such a comprehensive analysis can be conceptualized as APD. The underlying facets of such an APD are now outlined.

Table 6.3 Basic principles for designing controls for digital business objects and their challenges through Digital Transformation

Principles |

Interpretation and potential changes through Digital Transformation |

– Verifiability |

With shortening application lifecycles, new processes (and related controls) need to be defined in order to allow to chronologically re-examine the validity of transactions across IS. Particularly the availability of “raw” data and master data used by replaced previous IS needs to be safeguarded. For documents, transparent measures for indexing need to be introduced. |

– Transparency and clarity; – Completeness, particularly complete documentation of all transactions |

With increased business process flexibility, each documentation or reporting process requires a transparent and easily comprehensible description including involved systems, data sources, data types, and processing at the time of reporting. Such information should be integrated into business process intelligence applications in order to automatically verify and control the proper recording of changes. Time limits for documenting all related transactions and provisions (controls) will have to be complied too. |

– Accuracy and truth; – Timely booking and record storage; – Immutability of records and stored data |

With increased diversity of data and larger numbers of data processing IS, securing timely and immutable recording requires additional processes dedicated to design controls on process level that are sufficiently flexible to interpret and record the used application systems’ data access and management functions (including plans for distributed disaster recovery). |

– No record without evidence; – No record without offsetting entry (contra account); – Abbreviations must be comprehensible |

With increased diversity of data formats (e.g., file types) as well as number and distribution of systems, documenting (historiography) requires dedicated new systems for storage of electronic documents for the defined record retention periods in formats which are readable even after major application software changes. (Thus, some file formats will not fulfil related compliance criteria). Some countries (e.g., Germany) require to enable direct access options to such records. Related master data, accounts and additional information such as abbreviations and descriptions need to be made transparently available to third parties in such cases, too. (This might not hold for emails or other types of communication message formats which can often be considered carriers of relevant data and which can thus be deleted). |

APD – a business process view on AIS

Requirements and boundary conditions for procedural documentations

Following the verifiability principle, independent from the technical implementation, reporting, documenting and control processes need to be made transparent – which is contributing to both, design of internal controls and management processes as well as meeting compliance requirements. Procedural documentations in general cover both organizational processes as they are carried out and technical processes as they should be instantiated. In view of the Digital Transformation context, particularly the latter aspect deserves attention: APD in this regard needs to be chronologically versioned and stored just as thorough as the reported data itself. The technical process documentation for electronic documents, for instance, involves the information origin (data input event), indexing, processing and storage, measures to safeguard unambiguous retrieval and machine-based analysability, and protection against loss and manipulation/falsification as well as reproduction.

It has been only recently, in November 2014, with effect from January 2015, that the German federal ministry of finance has introduced “principles to ensure the due maintenance and preservation of books, records and documents in electronic form, as well as for data access (BMF Germany, 2014)”.2 These principles extend previous formal requirements for IS-based handling of electronic records,3 and give some provisions that predominantly motivate the introduction of APDs as a systematic method to safeguard compliance to various legislations.4 In the case of Germany, missing or insufficient APD documentations potentially lead to unfavourable circumstances for the entire accounting system and, hence, the enterprise. For instance, this situation can lead to sanctions, such as estimation of tax bases by authorities, assigning the burden of proof to the firm, possibly consequences within criminal tax law, fines, determination of missing effective annual financial statements, elimination of subsidies, or withdrawal of the legal basis for profit distributions. Such sanctions – if in effect in a particular business setting – in themselves provide a good incentive to engage in design of an appropriate APD. Nevertheless, a second impetus might be the improvement and maybe evolutionary adaption of AIS, with regard to an increasingly changing business context, and requisite adaptions on the IS. This second aspect will be discussed further below.

The following paragraphs outline implementation aspects of APD. While the presented suggestions are informed by recent German legislation, they provide guidelines for firms in any legal or business setting, as they can be considered minimum requirements to capture relevant “adjusting screws” during change and particularly, Digital Transformation processes.

Implementing procedural documentations

Hence, the objectives of creating an APD are first of all the proof of completion of the regularity principles as defined by the local legislation. All AIS-based finance and accounting procedures need to be available in a way that third-party authorities or external consultants can validate them with appropriate effort. This requires a comprehensive documentation that covers all specific procedures relevant to accounting and reporting. In particular, the management of transactions and documents as pieces of evidence needs to become transparent; the description of how documents are received and recorded, processed, and stored/retrieved is defining the core of an APD.

Basic questions an APD needs to answer are (adapted from AWV, 2015, p. 4):

• How are document input and document identification organized?

• How is the completeness of the collected documents ensured?

• How are documents ordered and where are the documents stored?

• How is the processing of conventional paper documents and born digital documents paralleled?

• How is the storage location (e.g., conventional file folder or archival system) secured against unauthorized access and against loss?

• Who has access to the storage location and to sorting functionalities?

• How often and in what way do accountants, managers, or third parties (e.g., corporate accounting or tax consultancies) receive the documents?

• How do you ensure that all affected persons know about and support above aspects?

• How do you ensure that the evidence is not destroyed before the end of the retention periods?

Following these examples, an APD needs to consider several important aspects. In principle, each IS involved to data processing, both AIS and related systems, require their own dedicated representation in an APD stating in which way or to what extent above questions have been implemented on the respective individual technical basis. Also, the Internal Control Systems (ICS) need to be part of the APD. Further, two basic processes need to be documented, i.e. the documentation function including capturing, processing, displaying and storing documents; and the scanning function, describing the capture of paper-based input information.

Usually, the components, or building blocks, of APD are:

1 General description of the documentation business process (what is in, what is out);

2 APD accountant user manual (to be used also by other stakeholders in the accounting and finance context);

3 Technical system documentation;

4 Operational procedures documentation.

In order to reach the verifiability requirement, it will be beneficial to link these components through an integrated business process management approach. In the following paragraphs, the components are presented in short.

Component 1: general description of the documentation business process

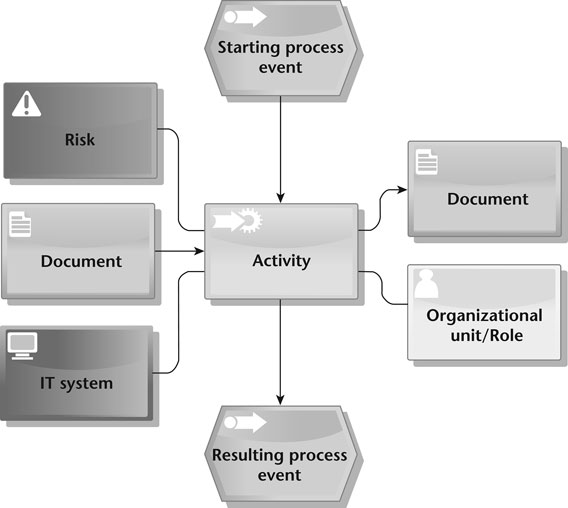

This description should use a visual and easily understandable approach to document and represent all relevant business processes, i.e. comprising activity flows and related events, the linked application systems, as well as documents and risks. For instance, the event-driven process chain (EPC) of the ARIS methodology (Scheer, 1992; Rosemann and van der Aalst, 2007; van der Aalst, 1999) can provide a suitable instrument that is also software-supported and can inform IT Management (Rahimi et al., 2016). Figure 6.1 illustrates core elements of an EPC: Positioning activities in the centre of the business process, organizational units or roles associated to or responsible for the activity can be defined; input and output (generated) information can be explicated, and related risks and controls can be documented. Using software support to BPM each of these elements is represented as a database entry which enables easy handling and retrieval, and is the basis for business process intelligence, i.e. the automatic detection of flaws in the actually instantiated processes, if the APD is linked with the operative systems.

In this way, in principle, the entire Internal Control System (ICS) can be represented (and eventually controlled). Particular controls that can be modelled are for instance: Access rights and related security concepts, separation of functions (e.g., the originator of a document does not approve it), validity checks, data entry coordination/checks, processing controls, IT system failure controls, safety measures against data and software manipulation (which need to be adapted to system complexity), and others. Using software-based business process modelling, it is easier for third parties to access and validate related accounting and reporting procedures – including direct links to their implementation, also in case of procedural or implementation variants. Contemporary BPM software often also enables the automatic generation of process models on basis of search/retrieval functionality, e.g., when searching for activities affected by failures in particular system functions.

Figure 6.1 Basic objects and modelling pattern for an event-driven process chain (created with ARIS Express software/software AG)

Component 2: APD accountant user manual

When using a software-based APD, a user manual should be provided for all roles involved, in order to safeguard proper handling of the system by users. While for some cases the software provider’s manual will suffice, in many cases configurations or customizations will make an enterprise-specific manual necessary. The manual should cover:

• General description of the IT application, its objectives and use cases;

• Listing and explanations of all application systems, their interrelations and sub-systems;

• Types and meaning of input masks including data entry fields;

• Visualizations of all application-internal processing steps/procedures;

• Explanation of modalities that facilitate data collection and analysis; as well as

• Separate documentation and explanation of the Internal Control System (ICS), e.g., to understand and reproduce configurations (parameters) and defined procedures.

Component 3: technical system documentation

The technical system documentation has two objectives: First, it defines boundary conditions for and measures to maintain ordinary (undisturbed) system operation. Second, it serves as provision of guidelines and measures in case of disturbances, e.g. to ensure ordered emergency operations. It should predominantly contain IT-specific hints and parameters for technical staff, and allow for system maintenance for third-party providers. In this respect, it is helpful to provide for easily comprehensible descriptions, because in emergency cases qualified external experts may need to reproduce the applications’ processing steps in an adequate timeframe without expertise in the used programming languages. This relates particularly to processing functions and rules, which, for reasons of verifiability, exclude pure source code documentations from the APD. The following areas and factors need to be described:

• Objective of the application system;

• Data organization and data structures;

• Changeable table content used in the booking process;

• Processing rules including input and processing controls;

• Program internal error handling procedures;

• Code lists; and

• Interfaces to other systems or modules.

Component 4: Operational procedures documentation

The subject of the operational procedures documentation is to explain the correct application of the accounting procedures. Among other factors it covers:

• Security concept;

• Data backup strategies and procedures;

• Processing evidence (protocols of processing and synchronization);

• Nature and contents of the release procedure for new and modified applications; and

• Listing of available programs including versioning evidence.

Table 6.4 provides an example of an operational procedures documentation of the security concept implementation.

The principle process of creating an APD is illustrated in Figure 6.2. The figure shows the principal sequence of steps; single steps usually need to be iteratively detailed along the process. Initial step should be the definition of responsibilities and process owners, i.e. describing the distribution of roles responsible for particular business processes and/or functions. Further steps are the creation of business process models of relevant parts of the enterprise, particularly the accounting and finance processes and activities; then, descriptions of hardware, software and technical procedures follow and detail the business process models.

When creating an APD, in practical settings it has proven helpful to first create a master document that serves as a navigation portal to all other related information sources. Such secondary sources comprise (1) procedural documentations (including business process models), (2) manuals and technical documentations, (3) contracts and protocols, and (4) operating procedures and functional descriptions. This has proven efficient for maintenance of the APD. On the one hand, when changes need to be recorded throughout various linked documents and when responsibilities need to be assigned for particular parts of the APD. In this respect, it is important to notice that the APD needs to mirror the correct application software versions or respective variants of procedures as they are applied/used in practice. Vice versa, employees need to be briefed in order to actually “live”, i.e. consciously comply to the provisions of the APD, in their day-to-day work. Thus, during the maintenance phase, regular control and updating of all elements of an APD are required.

Table 6.4 Example of an operational procedures documentation of security concept implementation

Chapter/Aspect |

Contents |

1 Introduction |

(Scope and guidelines for use of the manual) |

2 Inventory analysis |

Overview: Facilities, IT systems, IT applications, network plan, etc.; (Aspects to cover: availability, integrity, confidentiality) |

3 Vulnerability/ Risk analysis & measures |

3.1 Physical security: fire protection, security systems, power supply, emergency power supply, etc. 3.2 Logical security 3.2.1 Hardware (Intra) security: servers, workstations, etc. 3.2.2 Software (Inter) security: email (incl. spam), Internet, virus scanners, etc. 3.3 Organisational security: IT policy, authorization concept, data backup concept, etc. |

4 Emergency management |

4.1 Risk analysis 4.1.1 Analysis of the core processes of the company 4.1.2 Analysis of IT services and failure scenarios 4.1.3 Threat/effects analysis on failure of individual core processes 4.1.4 Legal requirements to be considered 4.2 Process-oriented emergency planning 4.3 Maintenance of timeliness 4.4 Organisational contingency plans 4.5 Other analyses (of the specific emergency setting) 4.6 Emergency exercises and emergency manual |

5 Liability agreement with employees on proper data handling |

|

6 Restoration exercises (intermittent) |

|

7 Change history |

Figure 6.2 Sample process for developing an APD

Regarding the lifetime of an APD, its retention time is generally equivalent to those of the applied AIS and the relevant data as legally prescribed. Therefore, each update and change needs to be documented through a reproducible versioning history of the entire APD documentation.

AIS, BPM, ITM, and future business planning

At first glance, the requirements for creating an APD might seem bureaucratic, and promising significant additional effort to customary reporting practices. In fact, in order to make IT Management more agile also with respect to accounting and finance functions, the APD establishes a crucial instrument that can be used to diagnose the enterprise for issues in compliance and IT security, and to design measures for preventing damages.

On another level, BPM is the basis to allow for an evolutionary design of enterprise systems, and particularly, AIS. With Digital Transformation, the agile, ad hoc design, configuration and deployment of application software for business needs becomes increasingly prominent (Pahlke et al., 2010; Neumann et al., 2014). The software development and deployment process then needs to be conceived as an iterative cycle that predominantly relies on participative improvement of application software (Abrahamsson et al., 2009; Cao et al., 2009). BPM – particularly through its visual representations – thus builds a basis to discuss process improvements, alternatives or variants between operationally involved staff, accountants and other company stakeholders. It also enables simulations on basis of process designs and operational process data with a view on business and operations strategies – without letting risks and compliance out of sight.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to expressly thank Mr. Thomas Martin and Mr. Helmut Heimfarth for their support on German legislation and their insights to practical applications of accounting procedure documentations.

Notes

1 These aspects complement on a process level the well-known risks inherent to AIS and financial reporting systems (FRS), such as incorrect general ledger accounts, etc., which may result in misstated financial statements and other reports, and which are subject to sanctions through Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, for instance (see e.g. Hall, 2011, p. 362).

2 “Grundsätze zur ordnungsmäßigen Führung und Aufbewahrung von Büchern, Aufzeichnungen und Unterlagen in elektronischer Form sowie zum Datenzugriff (GoBD)”.

3 Previous important regulations and/or amendments were published in 1984, 1995, 2001, 2012.

4 See BMF Germany, 2014, p. 32.

References

Abrahamsson, P., Conboy, K. and Wang X. (2009). Lots done, more to do: the current state of agile systems development research. European Journal of Information Systems, 18(4), 281–284.

Anaya, L., Dulaimi, M. and Abdallah, S. (2015). An investigation into the role of enterprise information systems in enabling business innovation. Business Process Management Journal, 21(4), 771–790.

AWV (2015). Arbeitskreis für wirtschaftliche Verwaltung e. V., Auslegung der GoB beim Einsatz neuer Organisationstechnologien, Muster-Verfahrensdokumentation zur Belegablage, Version: V1.0 19. October 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.awv-net.de/cms/front_content.php?idcat=286.

Besson, P. and Rowe, F. (2012). Strategizing information systems-enabled organizational transformation: a transdisciplinary review and new directions. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 21(2), 103–124.

Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O. A., Pavlou, P. A. and Venkatraman, N. (2013). Visions and voices on emerging challenges in digital business strategy. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 633–634.

Bhimani, A. and Willcocks L. (2014). Digitisation, ‘Big Data’ and the transformation of accounting information. Accounting and Business Research, 44(4), 469–490.

BMF Germany, Bundesministerium der Finanzen, Grundsätze zur ordnungsmäßigen Führung und Aufbewahrung von Büchern, Aufzeichnungen und Unterlagen in elektronischer Form sowie zum Datenzugriff (GoBD), 14. November 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2017 from www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Downloads/BMF_Schreiben/Weitere_Steuerthemen/Abgabenordnung/Datenzugriff_GDPdU/2014-11-14-GoBD.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1.

vom Brocke J., Zelt, S. and Schmiedel, T. (2016). On the role of context in business process management. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 486–495.

Cao, L., Mohan, K., Xu, P. and Ramesh, B. (2009). A framework for adapting agile development methodologies. European Journal of Information Systems, 18(4), 332–343.

Christ, M. H., Mintchik, N., Chen, L. and Bierstaker, J. L. (2015). Outsourcing the information system: determinants, risks, and implications for management control systems. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 27(2), 77–120.

Hall, J. A. (2011). Accounting Information Systems, 7th ed., Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Hess, T., Matt, C., Benlian, A. and Wiesböck, F. (2016). Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Quarterly Executive, 15(2), 123–139.

Hsu, P-F. (2013). Commodity or competitive advantage? Analysis of the ERP value paradox. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 12(6), 412–424.

Krcmar, H. (2005). Informations Management. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag,

Majchrzak, A., Markus, M. L. and Wareham, J. (2016). Designing for digital transformation: lessons for information systems research from the study of ICT and societal challenges. MIS Quarterly, 40(2), 267–278.

Mathrani, S., Mathrani, A. and Viehland, D. (2013). Using enterprise systems to realize digital business strategies. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 26(4), 363–386.

Neumann, G., Sobernig, S. and Aram, M. (2014). Evolutionary business information systems. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 6(1), 33–38.

Pahlke, I., Beck, R. and Wolf, M. (2010). Enterprise mashup systems as platform for situational applications. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 2(5), 305–315.

Rahimi, F., Møller, C. and Hvam, L. (2016). Business process management and IT management: the missing integration. International Journal of Information Management, 36(1), 142–154.

Rosemann, M. and van der Aalst, W. (2007). A configurable reference modelling language. Information Systems, 32(1), 1–23.

Scheer, A. W. (1992). Architektur integrierter Informationssysteme: Grundlagen der Unternehmensmodellierung, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Trkman, P. (2010). The critical success factors of business process management. International Journal of Information Management, 30(2), 125–134.

van der Aalst, W. (1999). Formalization and verification of event-driven process chains. Information and Software Technology, 41(10), 639–650.