CHAPTER TWO

Anatomy of Charitable Fundraising

- § 2.1 Scope of Term Charitable Organization

- § 2.2 Methods of Fundraising

- § 2.3 Role of a Fundraising Professional

- § 2.4 Role of an Accountant

- § 2.5 Role of a Lawyer

- § 2.6 Viewpoint of Regulators

- § 2.7 Viewpoint of a Regulated Professional

- § 2.8 Coping with Regulation: A System for the Fundraising Charity

Chapter 2 describes the anatomy of charitable fundraising. The chapter summarizes the various methods of fundraising, the different roles of a fundraising professional, and the role of nonprofit accountants and lawyers. The chapter also describes various viewpoints of regulators and includes descriptions of certain factual aspects of fundraising for charity, including the types of organizations encompassed by the various laws and the rules of those individuals who are, along with the charities themselves, enmeshed in this regulatory process.

Certain basic factual aspects of fundraising for charity warrant summary before an analysis of federal and state governmental regulation of this type of fundraising.1 These aspects include the types of organizations encompassed by the various laws, the many fundraising techniques, and the roles of those individuals (other than the regulators) who are, along with the charitable organizations themselves, enmeshed in this regulatory process: the fundraising professionals, the lawyers, and the accountants.

§ 2.1 SCOPE OF TERM CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION

The many laws governing the process of soliciting gifts for charitable purposes principally apply, of course, to charitable organizations and those who raise funds for them. Thus, it is necessary to understand the scope of the term charitable organization as it is employed in these laws.

The term charitable organization as used in the state charitable solicitation acts has a meaning considerably broader than that traditionally employed under state law and under the federal tax law.2 Therefore, the soliciting organizations encompassed by the federal definition of what is charitable must comply with the requirements of federal regulation governing fundraising for charity as well as those of the various states (unless exempted). Some organizations, however, are tax exempt under federal law for reasons other than advancement of charitable purposes but are still obligated to comply with the panoply of state and local charitable solicitation laws.

The federal tax law definition of the term charitable is based on the English common law and charitable trust law precepts. The federal income tax regulations recognize this fact by stating that the term is used in its “generally accepted legal sense.”3 At the same time, court decisions continue to expand the concept of charity by introducing additional applications of the term.4 As one court observed, evolutions in the definition of the word charitable are “wrought by changes in moral and ethical precepts generally held, or by changes in relative values assigned to different and sometimes competing and even conflicting interests of society.”5

For the most part, the institutions and other organizations that are subject to these laws are those that have their federal tax status based on their classification as charitable organizations. These are the entities categorized as charitable, religious, educational, scientific, or literary, or certain organizations that are engaged in fostering national or international amateur sports competition.6 Each of these terms is defined in the federal tax law.

The term charitable in the federal income tax setting embraces a variety of purposes and activities. These include the relief of the poor and distressed or of the underprivileged,7 the advancement of religion,8 the advancement of education or science,9 the lessening of the burdens of government,10 community beautification and maintenance,11 the promotion of health,12 the promotion of social welfare,13 the promotion of environmental conservancy,14 the advancement of patriotism,15 the care of orphans,16 the maintenance of public confidence in the legal system,17 facilitating student and cultural exchanges,18 and the promotion and advancement of amateur sports.19

The federal tax law also encompasses organizations defined as charitable in the broadest sense;20 these include entities considered educational, religious, and scientific. Nonetheless, the term charitable as used in the federal tax context—including education,21 religion,22 and science23—is not as broad as the concept of tax exemption. Certainly, the term is not as far-ranging as the concept of nonprofit organizations. Stated another way, nonprofit organizations are not necessarily tax exempt, and tax-exempt organizations are not always charitable.

To be tax exempt under federal law, a nonprofit organization must satisfy the rules pertaining to at least one of the categories of tax-exempt organizations set forth in the Internal Revenue Code.24 In addition to those organizations that are recognized as charitable entities,25 the realm of tax-exempt organizations under federal law embraces social welfare (including advocacy) organizations,26 labor organizations,27 trade and professional associations,28 social clubs,29 fraternal organizations,30 veterans' organizations,31 and political organizations.32 Generally, with the exception of veterans' organizations,33 contributions to these organizations are not deductible as charitable gifts.34

In general, the sweep of the states' charitable solicitation acts is not so broad as to encompass all nonprofit organizations, nor is it so broad as to encompass all tax-exempt organizations. For example, these laws do not normally embrace trade and professional associations35 that are financially supported largely by dues (payments for services), rather than by contributions. Likewise, they do not normally cover private foundations,36 which, while charitable in nature, do not usually solicit contributions. By contrast, these laws are likely to be attributable to organizations (other than purely charitable ones) that are tax-exempt but cannot attract deductible contributions,37 or are eligible to receive deductible contributions but are not usually regarded as charitable organizations, such as veterans' groups.38

Generally, the organizations that need to be concerned with the state charitable solicitation laws are the following:

- Churches and other membership and nonmembership religious organizations39

- Educational institutions, including schools, colleges, and universities40

- Hospitals and other forms of health care providers41

- Publicly supported charitable organizations42

- Social welfare organizations43

Consequently, an organization that is recognized as a charitable entity under federal tax law, and that engages in fundraising, is (unless specifically exempted)44 assuredly subject to the state charitable solicitation laws. These laws may, however, also encompass other types of tax-exempt organizations that solicit contributions.45

§ 2.2 METHODS OF FUNDRAISING

Critical to an understanding of government regulation of charitable fundraising is an understanding of fundraising itself.46

Every charitable organization is entitled to receive and, indeed, welcomes support in the form of contributions. Contributed funds can be used only to support the goals and objectives that are consistent with the organization's stated mission—usually, to engage in one or more forms of charitable activity recognized in law. When goals, mission, and public benefits are communicated to the public as institutional needs, they can stimulate gift support. Replies are acts of philanthropy that are motivated by numerous factors, including a sincere concern and a willingness to help others, to improve quality of service, or to advance knowledge. Such voluntary responses, whether of time, talent, or treasure, uplift the human spirit because they are directed to a charitable organization.

Requests for contributions are conducted by one or more fundraising methods. Fundraising is, in itself, a unique form of communication that “promotes” and “sells” the product (cause) and “asks for the order” at the same time. There is a common perception that there is a single type of activity called fundraising and that all gifts are made in cash. Most regulatory approaches seem founded on this perception, as are public attitudes—both positive and negative—toward charitable solicitations. In fact, charitable organizations employ several methods and techniques to solicit contributions. Gifts can be in several forms (such as cash, securities, personal property, and real estate), all of which are embraced within the term fundraising. The one feature shared equally is the objective—to ask for a gift that benefits someone else.

Asking is simple. There were traditionally only three ways to fundraise: by mail, by telephone, or in person.47 Mail solicitation has been found to be 16 times less effective than personal contact, yet most fundraising uses this most impersonal of approaches. Organizing institutions and agencies to perform fundraising is much more complex and requires the careful, and sometimes simultaneous, application of many individual methods of solicitation by volunteers and employees working together. Each method of fundraising has its own characteristics regarding suitability for use, public acceptance, potential or capacity for success (gift revenue), and cost-effectiveness. Likewise, the reporting and enforcement aspects of regulatory systems—to be fair—should distinguish between the varieties of fundraising technique and their performance.48

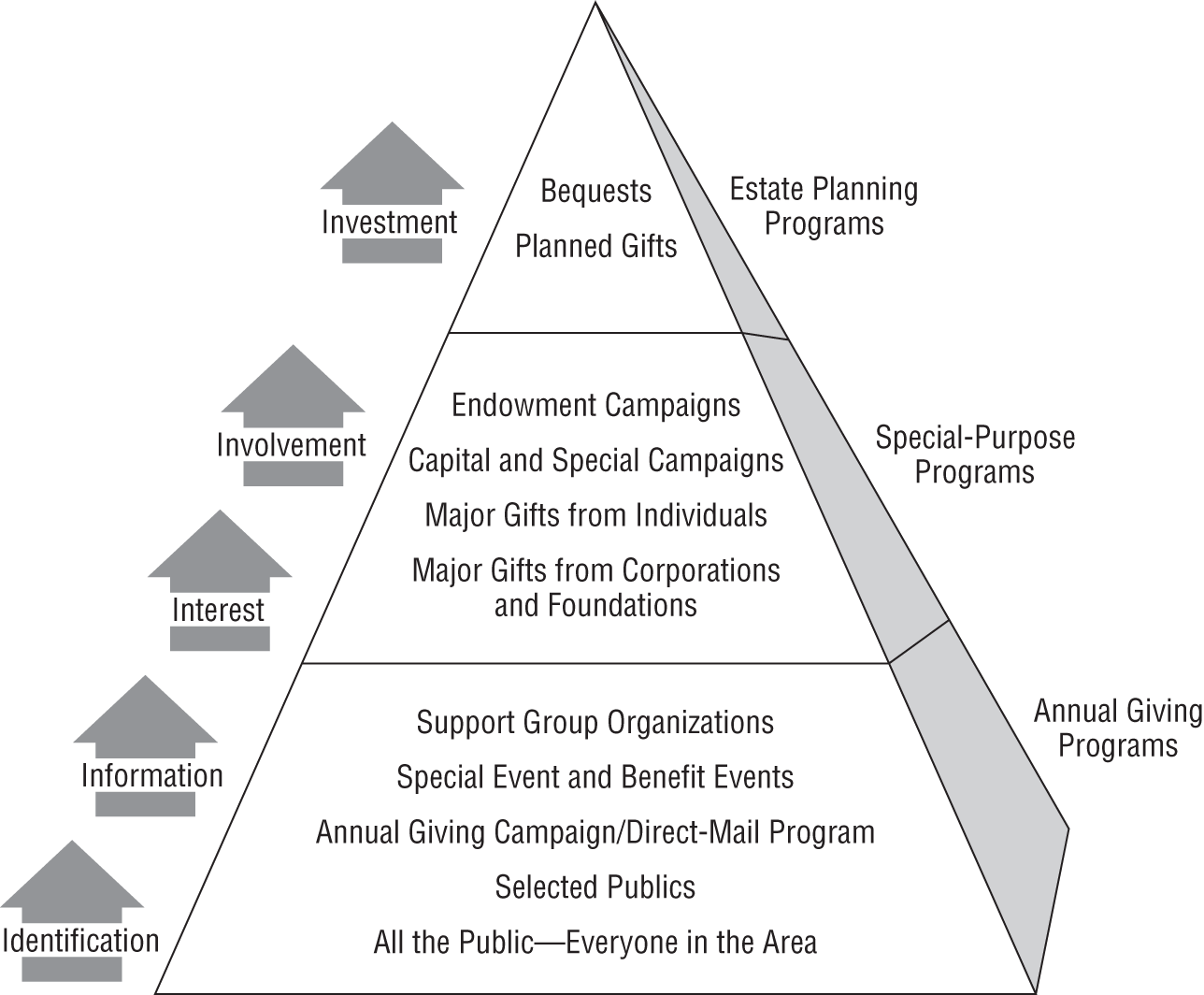

The methods of asking are best understood by dividing them into three program areas: annual giving, special-purpose, and estate planning. The “pyramid of giving” (see Exhibit 2.1, later in this chapter) illustrates how each area functions to perform individual tasks and to aid the progression of donor interest and involvement leading to increased gift results for each chosen charitable organization. Fifteen methods of fundraising are encompassed within the three program areas.

(a) Annual Giving Programs

The basic concept of annual giving programs is to recruit new donors and renew prior donors, whose gifts provide for annual operating needs. Some programs require only a staff professional to manage, but most require both staff and a volume of volunteer leaders and workers. Charities frequently conduct two or more forms of annual solicitation within a 12-month period; the net effect is to contact the same audience with multiple requests within the year. Churches make appeals weekly through the collection plate; United Way uses payroll deductions to ensure frequent payments. Such gift support is basic to the financial success of these organizations; their needs are urgent, and the funds are consumed immediately upon receipt.

The design behind the choice of any of these several methods offered during any one year is always the same—to recruit new donors and to renew (and upgrade) the gifts of the prior year's donors. Some donors prefer one method of giving over all others because they are most comfortable with that style. For example, benefit events are popular because they include attendance at social activities. Multiple-gift requests to present donors will increase net revenues faster than efforts to acquire new donors, because present donors are the best prospects for added gifts. No organization will be able to use every fundraising method (chiefly because of donor resistance or saturation), so rational selections are required.

A brief explanation of each method and its special value to the annual giving process is presented as follows, arranged in the order of least productive to most efficient.

- Direct Mail/Donor Acquisition. Direct mail/donor acquisition fundraising uses direct mail response advertising (usually third class, bulk rate) in the form of letters to individuals who are not present donors, inviting them to participate at modest levels. One of the best methods to find and recruit new contributors, this program is perhaps best known to the public because people receive so many mail requests. Usually a charity can expect only a 1 to 2 percent rate of return on bulk mail requests, but this is considered satisfactory. Successful “customer development” may require an investment of from $1.25 to $1.50 to raise $1.00, a formula well accepted in for-profit business circles but often criticized within charitable organizations. The value of new donors is not their first gift, however, but their potential for repeat gifts. Such first-time donors, with care and attention, can become future leaders, volunteer workers, and even benefactors.

The mail process includes (a) selecting audiences likely to respond to this organization;49 (b) buying, renting, or leasing up-to-date mailing lists of audiences selected; (c) preparing a package containing a letter signed by someone whose name is recognized by most people, a response form with gift amounts suggested, a reply envelope, and a brochure or other information about the charity or the program offered for gift support; (d) scheduling the “mail drop” during the most productive times in the year for mail solicitation (October through December, March through June); and (e) preparing for replies, including gift processing, setting up donor records, and sending thank-you messages.

- Direct Mail/Donor Renewal. Direct mail/donor renewal fundraising is used to ask previous donors, who are the best prospects for annual giving, to give again. If some contact has occurred since the first gift, such as a report on the use of their gifts to render services to others, it is likely that 50 percent of prior donors will give again—at a minimum cost to the organization of a renewal letter. A feature called upgrading, a request asking donors to consider a gift slightly above their last gift, works 15 percent of the time, and has the added value of helping preserve the current giving level. Prior donor support is predictable income for organizations that can estimate their ability to meet current needs because of committed levels of proven donor support.

- Telephone and Television. Telephone calls to prospects and donors permit dialogue and are more successful than direct mail. Public response is not high (around 5 to 8 percent), perhaps because of the intrusive nature of phone calls and their frequent use by for-profit organizations. Television solicitation is more distant but is the best visual medium to convey the message (televangelists already have perfected this technique).50 Both methods are expensive to initiate and require the instant response of donors (only 80 percent of pledge collections may be realized).

- Special and Benefit Events. Special and benefit events are social occasions that use ticket sales and underwriting to generate revenue but incur direct costs for production. While popular, especially with volunteers, these events are typically among the most expensive and least profitable methods of fundraising in practice today. Events include everything from a bake sale and car wash to golf tournaments and formal balls. If well managed, they should produce a 50 percent net profit. While most fundraising staff deplore the energy and hours required to support events, their greater value is in public relations visibility, both for the charity and its volunteers.

- Support Group Organizations. Support groups are used to organize donors in a quasi-independent association around the charitable organization. Membership dues and sponsorship of events are used as revenue sources as well as “friend-raising” opportunities. Support groups are like civic organizations, with a board of directors and active committees, except that their purposes are committed to one charity (e.g., an alumni association). Valuable for their ability to develop committed annual donors, to organize and train volunteers, and to promote the charity in the community, support groups also require professional staff management. Smaller charities should consider support groups to secure annual gifts as well as the volunteers needed to produce benefit events and to aid the organization in other ways when needed.

- Donor Clubs and Associations. Donor clubs and associations are donor-relations vehicles, similar to support groups, that are designed to enhance the link between donor and charity, thereby helping preserve annual gift support. Most organizations use higher gift levels (say, $1,000 and up) and prestigious names (e.g., President's Club) to separate these donors from all others. The clubs' selectivity and privileges help justify the higher gift required, which is rewarded by access to top officials and other benefits. Donor club members also represent a concentration of major gift prospects, whom charitable organizations treat as benefactors, and whose cultivation will pay dividends in the future.

- Annual Giving Campaign Committees. Campaign committees are volunteer committees of peers using in-person solicitation methods to recruit the largest and most important annual gifts. The performance of such a committee will be the most lucrative of all the aforementioned annual giving methods. The committee is structured as a true campaign, with a general chairperson and division leaders for individual, business, and corporate prospects. After making their own contributions, each volunteer may be assigned from three to five prospects to visit and with whom to discuss an annual gift decision. Donors are receptive because someone they respect has taken the time to call on them on behalf of an organization. The volunteers also can report that they have made their own personal contributions.

- Other Annual Giving Methods. Several other methods can also develop gift support on an annual basis:

- Commemorative Giving. A commemorative gift to a charity has the dual effect of honoring the recipient and aiding the donor's favorite charity at the same time. Most often, these gifts are memorials following the death of a family member, friend, or business colleague, and are directed by the family to their favorite organization. Commemorative gifts can also be given to mark a birthday, anniversary, promotion, graduation, or other important occasion, or to honor a friend, physician, or teacher.

- Gifts in Kind. Instead of cash, donors can make gifts of goods and services that can be used by the recipient organizations (such as Goodwill Industries, Salvation Army, St. Vincent de Paul Society) in their program activities. Businesses often donate products or excess merchandise, either for direct use (food or equipment) or for use as a benefit door prize or auction or raffle item.

- Advertisements in Newspapers/Magazines. Advertising, while the least likely solicitation method to stimulate a response, can promote an organization, a special campaign, a form of giving, or other purpose. Usually, direct mail or telephone follow-up is required to maximize the gift response from such multimedia techniques.

- Door-to-Door and On-Street Solicitation. While on-street solicitation is less common today because of limited volunteer time, some organizations benefit from “cold calls” during neighborhood drives because the public recognizes the organization's name (e.g., the American Cancer Society's “Women's Walk”) or has come to trust the organization's purposes (e.g., the Salvation Army's bell-ringers, chimney box, and red pot for collections at Christmastime). The difficulty in recent years has been abuse of public trust by a few organizations or individuals who “hustle” the public too hard or who run afoul of local regulations restricting solicitation, such as in airports and other public areas.

- Sweepstakes and Lotteries. Where legal, charities can benefit from such forms of public solicitation as sweepstakes and lotteries. Most charities, however, prefer to avoid areas of questionable practice, which too often are viewed by the public as forms of gambling. Bingo remains the exception, but it too is carefully regulated and supervised.

- Las Vegas and Monte Carlo Nights. Again, where legal, Las Vegas and Monte Carlo nights can develop gift revenues for a charity. State and local regulations for conduct of these events are strict, and may include a 5 to 10 percent fee taken from net proceeds. Like other special and benefit events, “casino” nights are hard to manage profitably because of high direct costs and overhead expenses.51

- Mailings of Unsolicited Merchandise. The theory behind the practice of mailing unsolicited merchandise is that it engenders guilt in the recipients—presumably, recipients would feel guilty keeping something of value sent to them and thus would be more likely to respond with gift support. This type of method is less popular today because postage and material costs, along with public resistance (lack of response), are rising.

- In-Plant Solicitations. Public solicitation in the workplace is usually controlled by the employer. Where in-plant solicitations are permitted, some employees resist being “cornered” and “pressured” to give. Usually, only United Way or other federated campaigns have been allowed into the workplace for this type of solicitation.

- Federated Campaigns. Federated campaigns are communitywide solicitations organized to support a large number of civic, social, and welfare organizations in the community with a single, once-a-year fund drive. Public acceptance is high, management and fundraising costs are low (under 20 percent), and a “campaign period” is observed. Federated campaigns, such as those of the United Way and the Combined Federal Campaign, are usually directed to local corporations for annual gifts and to their employees (or to government employees), who are allowed to use payroll deduction. These campaigns require cooperation from those charitable organizations being supported, who must refrain from their own solicitations during the campaign period.

(b) Special-Purpose Programs

A successful base of annual giving support permits the charitable organization to conduct more selective programs of fundraising that will secure major gifts, grants, and capital campaigns toward larger and more significant projects. A request for large gifts differs from annual gift solicitation because the request is for a “one-time” gift, allows a multiyear pledge, and is directed toward one specific project or urgent need. Likely donors are skillful “investors” who will respond to a major gift request only after researching the organization and determining whether the project justifies their commitment. If the request fails their examination, it is likely to receive only token (or no) support.

Following is a brief explanation of how the three forms of special-purpose fundraising are employed.

- Major Gifts from Individuals. It takes courage to ask someone for $1 million. Current and committed donors are the best prospects. Before the request is made, careful research should ascertain the prospect's financial capability, enthusiasm for the organization, preparedness to accept this special project, and likely response to the team assembled to make the call. Also important is an early resolution of the donor recognition to be offered (election to the board, name on a building, or both). The project must be a “big idea,” worthy of the level of investment required, perceived as absolutely essential, and a unique opportunity offered only once. In short, major gift solicitations should be performed as though they are a request for the largest and most significant gift decisions from these donors at this point in their lives.

- Grants from Government Agencies, Foundations, and Corporations. Separate skills and tools are required to succeed at grant-seeking. Grants are institutional decisions to provide support based on published policy and guidelines that demand careful observance of application procedures and deadlines. The decision is made by a group of people and, because of limited dollars, only one grant may be given for every 25 to 50 requests received. Usually, for a grant proposal to be accepted, the organization and its project must perfectly match the goals of the grantor.

- Capital Campaigns. A capital campaign is clearly the most successful, cost-effective, and enjoyable method of fundraising yet invented. Why? Because everyone is working together toward the same goal, the objective is significant to the future of the organization, major gifts are required (all through personal solicitation), start and end dates are goal markers, activities and excitement exist, and more. A capital campaign is the culmination of years of effort, both in design and consensus surrounding the organization's master plan for its future, which depends on experienced volunteers and enthusiastic donors. When everything comes together in a capital campaign, the result is success.

(c) Estate Planning Programs

An increasingly active area of fundraising involves gifts made by a donor now, to be realized by the charitable organization in the future. The term gift planning best describes this concept. These gifts either transfer assets to the charity now, in exchange for the donor's retaining an income for life, or transfer the remaining assets at the donor's death. This planning allows donors to remember their favorite charities in their estate and to plan gifts of their assets, now or at death. These gift decisions are usually made by donors who have some history of involvement and participation with the charities named in their estate and speak loudly of the donors' trust and confidence in the organizations and their future.

The four broad areas of planned giving are guided by income tax, gift tax, and estate tax law, plus layers of changing regulations. Estate planning is perhaps the single area of fundraising in which the tax consequences of giving are most prominent.

- Wills and Bequests. The easiest way for donors to leave a gift is to specify in their will or living trust that “ten percent (10%) of the residue of my estate is to go to XYZ Charity.” Organizations should provide donors with suitable but simple bequest language, to encourage them to include the organization in their will. These gifts may be outright transfers from the estate or may involve funding by means of a charitable trust created by a will.

- Pooled Income Funds. A “starter gift” to show donors how gift planning works can be made by means of a pooled income fund. Individuals may join a “pool” of other donors whose funds are commingled, with interest earnings paid out according to a pro rata shares distribution based on the annual value of the invested funds. Similar to mutual funds, pooled income funds require donors to execute a simple trust agreement and transfer cash or securities to the charity, which adds their gift to the pooled income fund. Upon a donor's death, the value of their shares is removed from the fund and transferred to the charity for its use.

- Charitable Remainder Gifts. Major gifts of property with appreciated value make excellent assets to transfer to a charitable organization in exchange for a retained life income based on the value of the gift at the time of transfer. These gifts are especially valuable to donors planning their retirement income and distribution of their assets. The structure of the trust agreement may be as a unitrust, annuity trust, or gift annuity. While the legal structure of the three agreements is slightly different, the charity in each case assumes responsibility to manage the asset or its cash value and to pay the donor an income of 5 percent at least annually.

- Life Insurance/Wealth Replacement Trust. Any individual may name his or her favorite charity as a beneficiary, in whole or in part, of a life insurance policy. This decision qualifies the value as a charitable contribution deduction. Some charitable organizations offer their own life insurance product, and premiums paid to the charity represent annual gifts for tax-deduction purposes. The charity uses the funds to pay premiums on a policy it owns, which names the charity as the sole beneficiary. The advantage to the donor is that the charity recognizes the death benefit value as the amount “credited” as a gift by the donor. The wealth replacement trust concept is linked to a charitable remainder trust; the donor uses the annual income to purchase a life insurance policy, usually for the value of the asset placed in trust, and names his or her heirs as beneficiaries, thus transferring to heirs the same value upon the donor's death.

(d) Reasonable Costs of Fundraising

Few charitable organizations are able to make use of every fundraising technique. Usually, only mature fund development programs in established charities have the necessary numbers of volunteers, donors, and prospective donors as well as an adequate professional and support staff, budgets, and operating systems to coordinate such a massive effort with efficiency.

Most organizations begin with the need to define the audiences who will support their mission and to seek their first gifts. Thereafter, attention is focused on securing annual operating revenues to stay in business, which requires constant attention to the annual giving solicitation methods. The choice of method(s) depends on several factors, including the scope of the organization's mission and the cost of fundraising. If the cause is national, the broadest solicitation outreach will be needed through direct mail, which is most expensive. If the purpose is local, concentration can expand audience selection to everyone in the area—again, expensive. In time, major gifts, grant requests, capital campaigns, and estate planning may be included to balance overall program productivity and cost-effectiveness.

By contrast, several types of organizations have the ability to engage in multiple fundraising methods simultaneously and with high profitability. Colleges pursue alumni constantly (annual gift, class gift, reunion gift, capital campaign, estate planning, plus requests for time and talent in leadership roles and as volunteers and workers). Private colleges do not approach the public, but they often expand their solicitations to “anyone who walked across the campus one day.” Other organizations must appeal to the public because their cause, as well as their needs, requires them to reach out. Thus, advocacy groups combine fundraising with a call to action; churches, with the offer of a way to salvation; hospitals, with wellness education and provision of direct care; and so on.

Whatever the organization, its choice of fundraising method carries with it a differing cost-effectiveness performance. “Charities are not the same in how they perform fundraising nor does fundraising perform the same for every charity. Equally, efficient fundraising is not the measure of the importance or value of the cause.”52

Choice of method requires attention to cost-effectiveness measurement. It costs money to raise money, but what are the reasonable cost levels? Studies by the American Association of Fund-Raising Counsel, the National Society of Fund-Raising Executives (now the AFP), and the Association for Healthcare Philanthropy reveal that, on average, it costs 20 cents to raise one dollar after a solicitation program has been in operation for a minimum of three years. Reasonable cost levels for various methods of fundraising are given as follows.

(i) Direct-Mail Acquisition. Making the first sale, whether in for-profit sales or nonprofit fundraising, is expensive. Direct-response advertising is a popular and effective form of direct-mail acquisition used by both private and nonprofit enterprises. Reasonable cost levels for a nonprofit organization should not exceed $1.50 per dollar raised, with a corresponding 1 percent or higher level of participation (rate of return).

(ii) Direct-Mail Renewal. Once a donor is acquired, the effort to renew this gift, either in a few months or next year, will be more cost-effective. Renewal costs should be within 20 cents per dollar raised, with a 50 percent renewal rate among prior donors.

(iii) Special Events and Benefits. While highly popular with volunteers, benefits are expensive to conduct and usually are valuable for reasons other than raising money. A net goal of 50 cents per dollar raised against direct costs is the recommended guideline.

(iv) Corporations and Foundations. Solicitation of corporate and foundation support is a highly selective and competitive method of fundraising. Expenses should not exceed 20 cents per dollar raised.

(v) Planned Giving. Planned gifts, being complex and individually designed, require time to prepare and plenty of patience to mature. An average of 25 cents per dollar raised is the recommended guideline.53

(vi) Capital Campaigns. The most profitable, cost-effective, and productive fundraising method available is capital campaigns. These campaigns focus on big ideas and solicit big gifts, require personal leadership and solicitation by volunteers, have professional staff direction, and usually yield good results. Capital campaign costs should not exceed 5 to 10 cents per dollar raised.

Regulations that focus on costs compared with gift revenues treat unfairly the realities of fundraising performances by charitable organizations, whether old or new. Simple bottom-line analysis is inadequate, can be misleading, and seriously fails to understand the nature of individual organizations, their unique environment, and their separate capacity for raising charitable contributions.

New startup efforts (even for established charities) to begin a fundraising program are not likely to meet these “reasonable cost” guidelines for at least three years. Charities representing new causes or previously unknown or unpopular needs will be even less successful. The critical factors inherent in success—environment and capacity—also must reflect the realities surrounding the organization. A realistic analysis of local conditions will help set reasonable expectations based on factors such as availability of prospects, access to wealth, competition, local regulations, geography, style, public image, access to volunteers (including leadership), fundraising history, prior fiscal performance, volume and variety of fundraising methods offered, use of professional staff or consultants, existing donors for renewal and upgrading, established fund development office procedures, and more.54

§ 2.3 ROLE OF A FUNDRAISING PROFESSIONAL

Fundraising executives refer to the development process as their guide. This process includes (1) acquiring donors, (2) renewing and upgrading donors, and (3) maximizing donors. Each phase represents an increased capacity to support charitable organizations. The process starts at the bottom of the pyramid of giving (Exhibit 2.1). Identification of prospects from those publics available to each charity is accomplished through the several annual giving methods. Each individual donor's progression up the pyramid requires time for communication of information and development of interests and of a level of personal involvement with the organization (the “friend-raising” phase). Major gift opportunities, while less frequent, are usually centered in capital campaigns and represent a continuing investment in response to a rising commitment and enthusiasm for the programs and services of the organization. The ultimate investment decision is usually made last, is frequently the largest gift, and may even come as part of the distributions from a donor's estate.

Fundraising professionals are like symphony orchestra conductors. Before fine music can be produced, they need competent musicians, all the right instruments, the correct sheet music for each player, a concert hall, rehearsals, and an audience. Any one of the 15 fundraising methods can more easily be accomplished alone; activating many methods simultaneously takes skill in managing the process of moving everyone forward together, in the same direction, toward the same objective, and at the same time.

The desired net effect is to stimulate multiple forms of asking for multiple gift decisions from donors and prospects each year, while at the same time selectively soliciting larger gifts from a few who have demonstrated greater potential from previous gift performance. All of this should be timed to meet institutional needs with funds delivered on schedule.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Pyramid of Giving

(a) Types of Professional Fundraisers

Three types of professional fundraising executives work for and with charitable organizations to direct and manage fundraising programs. Legislation and regulation provide guidelines for the relationship between organizations and those who perform fundraising on their behalf, and distinguish among the three types.

- Fund Development Officer. A fund development officer is a full-time salaried employee of the organization and receives the same standard employment benefits of all other employees. Most regulations are silent about employees who perform fundraising, choosing rather to regulate the organization itself. The fund development officer designs the fundraising program in keeping with the organization's priority needs, selects the fundraising methods required to produce the income needed, and supervises operations on a daily basis. To make the development process work, the development officer must also set and meet goals and objectives; identify committees; assign functions and manage them successfully; recruit and train leaders and volunteers; hire and train staff; write policies and procedures, have them approved, and see that they are followed; prepare budgets and supervise expenses; perform and report results and analyses; keep confidential records accurately and discreetly; design and implement a donor recognition system; and more.

- Fundraising Consultant. A fundraising consultant is an individual or firm hired for a fee to provide services of advice and counsel to charitable organizations on the design, conduct, and evaluation of their fundraising enterprises. Most regulations require consultants to register with state authorities, file a copy of contracts for service, and be bonded when the handling of gift dollars will occur. Consultants are available to guide staff and volunteers on specific fundraising methods (direct mail, telephone, planned giving, capital campaigns, and the like), to perform objective studies and analysis of the design and conduct of comprehensive fundraising programs, and to provide executive search, marketing, public relations, and other services. Consultants do not usually conduct solicitations directly, nor do they handle gift money, but they can and do assist these efforts. Consulting staff can be retained to perform all of the duties of the fund development officer, usually for a specified period until full-time employees can be hired and trained.

- Professional Solicitor. A professional solicitor is an individual (or firm) who is hired, for a fee or on a commission or percentage basis, to perform a fundraising program or special event directly in the name of the organization, to solicit and receive all gifts, to deposit funds and pay expenses, and to deliver net proceeds to the charity. Legislation and regulation of professional solicitors are the most intense because of past conduct by those whose fees and expenses have been high and who have delivered net proceeds in the area of only 20 percent or less of gross revenues. Solicitor firms are more likely to attract smaller and newer organizations (or “noncharities” for whom the gift deduction is no longer allowed) who believe they lack the ability to mount their own fundraising programs and thus are easy prey to the sales pitch that promises gift revenue with no effort on the organization's part.

In making a choice among fundraising professionals, charitable organizations should compare their cost-effectiveness. Fund development officers and professional consultants perform similarly and produce net returns of from 75 to 80 percent of net income. Professional solicitors return 20 percent or less of net income.

Several other features that relate to the separate role of fundraising professionals are discussed as follows.

(b) Professional Associations

National and local organizations have expanded to meet the needs of fundraisers, one of the fastest-growing new service areas of employment available in the United States. As of the close of 2007, membership in the Association of Fundraising Professionals (AFP), formerly the National Society of Fund Raising Executives, which was founded in 1962, numbered more than 30,000 individuals in 175 chapters in the United States, 15 chapters in Canada, 5 chapters in Mexico, and 3 chapters in Asia. The Council for the Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) and the Association for Healthcare Philanthropy (AHP) provide similar trade association services to their members. The American Association of Fund Raising Counsel (AAFRC) represents many of the larger national firms whose members practice as consultants. Hundreds of others who practice fundraising as staff or consultants are not members of any society. Other professional associations, such as the National Council on Planned Giving, have emerged to meet the needs of specialists, and the Direct Mail Marketing Association includes members who service both for-profit and not-for-profit clients.

The primary purpose of these trade associations is to serve the members, usually by providing training in the profession through conferences, seminars, monthly meetings, workshops, journals, and newsletters. Efforts have begun to define a common curriculum of information organized along knowledge and experience levels to support career development. College curricula and degrees have been slow to develop, perhaps because of a lack of literature and a research base. Professional training, when linked to certification, can yield verification to members of their comprehension of basic principles plus a validation to employers of a level of competency.

(c) Accreditation and Certification

Licensure of fundraising professionals is not yet a serious consideration and could be unwieldy to implement, considering the more than 1 million tax-exempt charitable organizations doing business in the United States. Fundraising staff and consultants do benefit from participation in accreditation programs because they reflect a level of personal commitment to the craft and demonstrate levels of competency attained. Presently, the accepted certification programs are offered by the AHP and AFP.

(d) Standards of Conduct and Professional Practice

As with any emerging profession, common standards require time for development. Fundraising standards originated as codes of ethics but have since matured into standards of conduct and professional practice. While the AAFRC, AHP, CASE, and AFP have their own written texts in this area, they have not yet achieved a common standard to govern what is, in essence, the same form of activity.55

§ 2.4 ROLE OF AN ACCOUNTANT

An accountant serving a charitable organization that engages in fundraising also has a variety of responsibilities, as discussed in the following analysis.56 Accounting for fundraising costs is one of the most sensitive areas of financial accounting, reporting, and management for organizations that solicit funds from the public. The level of fundraising expenses with respect to contributions is generally perceived as an index of management performance. Amounts reported as fundraising expenses, accordingly, are carefully examined by organization constituents and directors, contributors, and regulatory agencies.

An accountant in an organization that solicits funds from the public has several important responsibilities, including accounting for fundraising costs in a manner that (1) is consistent with generally accepted accounting principles; (2) is consistent with the financial reporting requirements of state and other regulatory agencies; and (3) facilitates sound financial management of the organization.

(a) Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

Professional accounting literature applicable to not-for-profit organizations requires that organizations report fundraising expenses separately from other supporting expenses and program expenses.

Fundraising expenses generally include all costs involved in inducing others to contribute resources without receipt of economic benefits in return. Fundraising costs usually consist of the direct costs of solicitation (such as the cost of personnel, printing, postage, occupancy, and so on) and a fair allocation of overhead.

One aspect of accounting for fundraising costs is subject to considerable judgment—accounting for the joint costs (such as postage) of multiple-purpose materials, such as educational literature that also includes a request for funds. Formerly, accounting literature (and industry practice) was inconsistent on this issue. Some organizations allocated joint costs between respective functions. Other organizations did not allocate joint costs and reported joint fundraising and educational costs exclusively as fundraising expenses.

Functional allocation of multiple-purpose expenses is now required by the accounting profession in its most recent pronouncement on the subject, if certain criteria are met. Recommended bases of allocation include the content of the materials, the use made of materials, and costs associated with different functions.

(b) Financial Reporting Requirements

Nonprofit organizations that solicit funds in several states are confronted with a web of financial reporting requirements. Regulation of charities in different states is the responsibility of different agencies with different reporting requirements and different filing deadlines. In addition, charities are often subject to the registration and reporting requirements of local units of government.

Fundraising expenses frequently are a focus of state and local regulators. Different jurisdictions require different detail in reporting fundraising costs. Some states and municipalities have attempted to restrict the right of solicitation to organizations whose fundraising costs do not exceed a fixed percentage of contributions, but the federal courts have ruled this to be unconstitutional.

State and local regulation of charities is fluid and subject to unanticipated changes. Accountants, therefore, must closely monitor the reporting requirements of all jurisdictions in which their organization solicits funds from the public.

Accountants must also be alert to guidelines established by private “watchdog” agencies. These agencies establish “standards” for nonprofit organizations. Deviation from these standards may result in public censure and in sanctions, in the form of reduced or withheld contributions from corporations and other grantmaking organizations that judge potential donees and grantees on the basis of these standards.

(c) Financial Management

In addition to conforming with generally accepted accounting principles and with reporting requirements of various regulatory bodies, accounting for fundraising expenses should provide information that facilitates sound financial management.

Creation of information of this type usually requires a system of cost identification and cost allocation. Effective analysis of fundraising costs requires an accurate identification of fundraising cost components and an objective allocation of joint costs and overhead.

By relating the cost of various fundraising activities with the amount of contributions received—that is, identifying the cost of each dollar raised—fundraising policy may be enhanced and the results of fundraising activities may be improved.

§ 2.5 ROLE OF A LAWYER

The legal counsel who represents or otherwise works for a charitable organization that is ensnarled in regulation of its fundraising likewise has a multitude of responsibilities. In addition to all other tasks that must be undertaken in serving the organization, they should:

- Review the law of each jurisdiction in which the organization solicits contributions and advise on compliance responsibilities.

- See that all applications, forms, reports, and the like are properly prepared and timely filed.

- Assist the organization where it is having difficulties with enforcement authorities, such as by helping prepare a statement in explanation of its fundraising costs or by arguing its case before administrative staff(s), state commission(s), or court(s).

- Review and advise as to agreements between the organization and professional fundraisers and/or professional solicitors.

- Assist the organization in the preparation of annual reports and other materials by which it presents its programs, sources of support, and expenses to the general public.

- Keep abreast of recent developments in the law concerning government regulation of fundraising by charitable organizations.

One problem facing lawyers who represent charitable organizations in the fundraising setting warrants particular mention. It is common knowledge that some states regulate charitable fundraising more stringently than others. It is also common knowledge that the states will not proceed against charitable organizations that are not in compliance with their law without first contacting organizations and requesting their compliance. Thus, many charitable organizations decide to not register and otherwise comply with the law of one or more states until they receive a formal request from each state to do so. Consequently, the lawyer is often asked this question: Which states should the organization register in and which state's law can the organization “safely ignore” until or unless contacted by the regulatory authorities? The problem for the lawyer is that they ought not to counsel flouting or breaking the law. Thus, the lawyer should advise the charitable organization client that it must adhere to the law of every state in which it is soliciting contributions and not wait for some informal notice or otherwise wait “until caught.” The lawyer ought not to advise the charitable organization client to comply with the law in the “rigorous regulatory” states and “wait to see what happens” in the others.

There is one subject about which the law is nearly nonexistent: the extent to which a charitable organization must register and otherwise comply with state (and local) law when it is soliciting contributions by means of its website.57 Lawyers and others must await future developments for definitive answers on this point.

Occasionally, the argument will arise—either from charitable organizations or professional fundraisers, or both—that the states' charitable solicitation laws are inapplicable, either because the enforcement of them obstructs interstate commerce and/or that the law concerning use of the mails overrides state regulatory law. These contentions have been tried in the courts, have failed, and are not likely to have any currency in the future.

The lawyer's role in relation to fundraising regulation should not be performed in isolation but should be carefully coordinated, not only with the charitable organization's staff, officers, and governing board, but with other consultants, principally the accountant and the professional fundraiser.

§ 2.6 VIEWPOINT OF REGULATORS

As is attested to throughout the book, the methods and extent of government regulation of fundraising are controversial. This section provides the viewpoints of a seasoned regulator of charitable fundraising.58

Although the charitable sector makes significant contributions to society and has been experiencing astonishing growth, it is no different from any other sector of the economy in that it has its share of unscrupulous individuals who seek to profit by defrauding innocent donors out of their hard-earned income and, in some cases, their lifetime savings. These fraudulent schemes harm not only contributors, who respond in the mistaken belief they are helping charitable causes, but also the charitable community, in that each new scandal hurts legitimate charitable organizations by increasing skepticism in the giving public.

The states have the difficult, but essential, tasks of protecting their citizens from charlatans who prey on their charitable natures while challenging them to recognize that all are benefited when worthy charitable organizations are generously supported. The role of the states becomes even more critical when major governmental cutbacks shift the responsibility for relieving many of society's burdens to the charitable sector. The purpose of the states' charitable solicitation acts is to protect the states' residents and legitimate charitable organizations.

The state charitable solicitation acts generally serve two important purposes: (1) they allow the public to get basic information about organizations asking for contributions so donors can make better, more informed charitable giving decisions; and (2) they help protect state residents from charitable solicitation fraud and misrepresentation.

§ 2.7 VIEWPOINT OF A REGULATED PROFESSIONAL

Most fundraising professionals do not believe that their practices in assisting charities to acquire charitable gifts are in any way abusive to potential donors or other citizens. It is no surprise, then, that they find government regulation of philanthropy to be unduly restricting and a misdirection of resources. What follows is the view of one of these regulated professionals.59

The nonprofit organizations that collectively constitute the “third sector” of the U.S. economy are a loose and unorganized delivery system for services that are generally not profitable, are too cumbersome, or are too partisan for business or government to support. Our societal response is to fund these endeavors through private financial support of philanthropy. The impetus to modern philanthropy is the still rather vague and developing discipline of fundraising (also called development and/or financial resource development).

For the most part, the third sector is populated by well-intentioned, hardworking individuals whose dedication to a particular cause or goal takes precedence over personal gains and rewards. This description also includes the majority of fundraisers, particularly those whose careers are encompassed by employment solely as staff of nonprofit organizations.

The thinking of most practitioners is that the regulation of fundraising practices is similar to “preaching to the choir.” Although no precise sources of data are available concerning the verifiable amount of fraud or other abuse in fundraising, it can safely be said that the actual level is far lower than the general perception holds, and quite laudable when compared with other forms of activity in our society. By and large, the fundraising activities engaged in to benefit nonprofit organizations are conducted with an exceptionally high degree of honesty and professionalism.

Regardless of their intent or reason for being enacted, regulations are perceived by practitioners of fundraising as a breach of the public's trust in the operation of nonprofit organizations or, at the very least, regulations are a nuisance. The members of the third sector generally believe that well-run, well-intentioned nonprofit organizations do not abuse the public's trust. Existing accounting and audit procedures, along with other routine guards against fraud and the like, are seen as adequate to protect fundraising activities, by and large. To be regulated is to be insulted by the “public,” which the nonprofit organization and the fundraiser are working to assist. The real abuses are performed by “those other guys,” the unprofessionals who will do anything for a buck.

That perception of selfless service does not exempt fundraisers from scrutiny, nor should it; however, such a perception, coupled with the decentralized and diverse nature of the third sector, creates a perfect environment for miscommunication, misunderstanding, and distrust with regard to fundraising regulation.

Although the regulated and the regulators have the same goal—the protection of the public from fraud and deception—the reality is that practitioners are generally unsupportive of regulation, and regulators are generally unaware of the third sector's nature and operations (concerning resource development) and of the impact that regulation has on delivery of services. In general, there is considerable confusion and too little action based on consistent dialogue and the understanding built by mutual respect.

Both extremes of regulation—too much and too little—are regrettable; however, to engage in any level of regulation with so little dialogue between concerned and affected parties is like running in the dark. Rather than spend precious resources and valuable time highlighting specific shortcomings and failures of regulation from either perspective, those who perceive a need for regulation and those who are to be regulated should develop simple and consistent communication. This communication could take several forms, such as annual or biannual meetings of representatives from fundraising professional associations and legislators and/or enforcement entities; testimony or position papers delivered during the regulatory development process; meetings, conferences, and symposia sponsored by philanthropic foundations interested in the health and well-being of the third sector; and the like.

The specific means of communications are not important if they are effective in stimulating and maintaining the much-needed dialogue. The real value lies in their ability to produce outcomes that answer some rather simple questions, such as:

- Are donors protected and is philanthropy nurtured?

- Are funds used to support those purposes for which they are solicited?

- Are the regulations fair to all nonprofit organizations?

- Can the regulations be evaluated for effectiveness?

Often, regulations are a reaction to a perceived form and level of abuse. The perception may be correct or incorrect; that is not the issue. The issue is that the enacted regulation rarely benefits from the type of exchanges described previously. Less or more regulation is not important; better regulation is.60

§ 2.8 COPING WITH REGULATION: A SYSTEM FOR THE FUNDRAISING CHARITY

(a) Monitoring of Compliance Requirements

An organization that is subject to a substantial number of the charitable solicitation laws—and that undertakes to register and report under them—should design a system by which it can remain abreast of its varied compliance responsibilities.

The state charitable solicitation laws are published as part of each state's code of statutes. County, city, and town ordinances are similarly published. Other “law” with respect to these statutes and ordinances will appear as administrative regulations and rules, administrative and court decisions, and instructions with regard to applications and report forms.

Therefore, the first step is to ascertain which of the 51 jurisdictions (50 states and the District of Columbia) do not have some form of a charitable solicitation act. At the present, there are three of these jurisdictions: Delaware, Montana, and Wyoming.

The second step is to identify the municipal ordinances that are applicable. No one has identified them all, but assuredly there are several in each state.61 (Probably the most well known and stringently enforced of these ordinances is the one in effect in the city of Los Angeles.)

The third step is to identify the jurisdictions in which, for one reason or another, the organization voluntarily refrains from conducting a solicitation.

The fourth step is to identify the status of the organization's compliance with the applicable solicitation laws. A typical evaluation would utilize the six items in this analysis of jurisdictions:

- States in which the organization is registered.

- States in which the organization is exempt from one or more requirements.

- States in which the organization is pursuing initial registration.

- States in which the organization does not know its status but is investigating its status.

- States in which the organization is registered but where one or more questions are being raised that may lead to revocation or modification of the registration.

- States in which the organization is registered but is operating under some type of conditional, temporary, or probationary status.

The fifth step is to identify any jurisdictions in which the organization has been prohibited from soliciting contributions.

The sixth step is to make an inventory of due dates for filing renewals of registration and reports.

The seventh step (an ongoing one) is to persist in all reasonable endeavors to remedy the organization's difficulties as reflected in the fourth (items 5 and 6) and fifth steps.

Any professional fundraiser or professional solicitor retained by a charitable organization has independent registration and reporting responsibilities. Therefore, the organization's compliance efforts should be carefully coordinated with those of its fundraiser(s), solicitor(s), or both.

(b) Public Relations

To responsibly, accurately, and promptly respond to inquiries from the general public, an organization should be prepared to disseminate an annual report upon request. (This may also be sent to others, without waiting for a request, such as members, donors, community leaders, and other organizations.) A form letter from the organization's president or executive director may be effectively used to transmit the report.

With today's heavy emphasis on the issue of fundraising costs, the annual report or like document should discuss the organization's fundraising program and costs.

(c) Record Keeping and Financial Data

A principal focus of this field of government regulation is fundraising costs. Therefore, management should make a substantial effort to accurately ascertain and record both direct and indirect fundraising costs. This process will require careful analysis of individuals' activities (so as to isolate the portion of their compensation and related expenses that is attributable to fundraising) and careful allocation of expenditures (where an outlay is partially for fundraising and partially for something else, such as program activities).

Fundraising costs must be reflected in the annual information return filed by tax-exempt organizations with the IRS.62 Although percentage limitations on fundraising costs are unconstitutional,63 some state laws require disclosure of these costs in a variety of ways.64

In any event, most organizations wish to be able to consider their fundraising costs “reasonable,” particularly in response to inquiries from donors or the media. Therefore, a fundraising organization should be prepared to demonstrate the reasonableness of its fundraising costs.65

NOTES

- 1. There are, of course, other forms of fundraising, such as fundraising for political parties and candidates; federal government regulation of these forms of fundraising is summarized in § 6.15.

- 2. See § 3.1.

- 3. Reg. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2).

- 4. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 6.3(c), Chapter 7.

- 5. Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150, 1159 (D.D.C. 1971), aff'd sub nom. Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971).

- 6. IRC §§ 501(c)(3) and 170(c)(2). The first of these provisions is the basis for federal tax-exempt status; the second is the basis for eligibility for donee status for purposes of the federal charitable contribution deduction. (Most organizations that engage in fundraising are able to offer their donors assurances that their gifts are deductible for federal and state income tax purposes because these organizations are described in IRC § 170(c)(2).) Organizations that are engaged in “testing for public safety” are referenced in IRC § 501(c)(3) but not IRC § 170(c)(2). The charitable deduction law is summarized at § 6.7.

- 7. Reg. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, §§ 7.1, 7.2.

- 8. Reg. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.10.

- 9. Reg. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, §§ 7.8, 7.9.

- 10. Reg. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.7.

- 11. Rev. Rul. 78-85, 1978-1 C.B. 150. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.11.

- 12. Rev. Rul. 69-545, 1969-2 C.B. 117. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.6.

- 13. Reg. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.11.

- 14. Rev. Rul. 76-204, 1976-1 C.B. 152. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.15(a).

- 15. Rev. Rul. 78-84, 1978-1 C.B. 150. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.15(b).

- 16. Rev. Rul. 80-200, 1980-2 C.B. 173. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.15(f).

- 17. Kentucky Bar Foundation, Inc. v. Commissioner, 78 T.C. 921 (1982). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.15(f).

- 18. Rev. Rul. 80-286, 1980-2 C.B. 179. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.15(f).

- 19. Hutchinson Baseball Enterprises, Inc. v. Commissioner, 73 T.C. 144 (1979), aff'd, 696 F.2d 757 (10th Cir. 1982). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.15(c). Also, IRC § 501(j). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 11.2.

- 20. The U.S. Supreme Court held that all organizations encompassed by IRC § 501(c)(3), including those that are “educational” and “religious,” are “charitable” in nature for federal tax law purposes (Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983)).

- 21. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 8.

- 22. Id., Chapter 10.

- 23. Id., Chapter 9.

- 24. The Internal Revenue Code provides for tax-exempt status under IRC § 501(a) for those nonprofit organizations that are listed in IRC § 501(c). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapters 13–19. Other categories of tax-exempt organizations are described in IRC §§ 521, 526, 527, and 528. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapters 17, 19. Governmental entities are also tax exempt. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, §§ 7.14, 19.21.

- 25. That is, organizations described in IRC § 501(c)(3).

- 26. Organizations described in IRC § 501(c)(4). See Law of Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 13. Social welfare organizations are the type of noncharitable organizations that are most likely to be subject to the state charitable solicitation acts.

- 27. Organizations described in IRC § 501(c)(5). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 16.1.

- 28. IRC § 501(c)(6). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 14.

- 29. IRC § 501(c)(7). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 15.

- 30. Organizations described in IRC § 501(c)(8), (10). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 19.4.

- 31. IRC § 501(c)(4) or § 501(c)(19). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 13, § 19.11.

- 32. IRC § 527. See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 17.

- 33. Contributions to veterans' organizations are deductible by reason of IRC § 170(c)(3).

- 34. Only organizations described in IRC § 170(c) are eligible charitable donees. See supra note 6.

- 35. See supra note 28.

- 36. See Private Foundations.

- 37. E.g., organizations described in IRC § 501(c)(4). See supra notes 26 and 34.

- 38. IRC § 501(c)(19). See supra note 31.

- 39. IRC § 170(b)(1)(A)(i). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 10.

- 40. 40 IRC § 170(b)(1)(A)(ii). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, Chapter 8.

- 41. IRC § 170(b)(1)(A)(iii). See Tax-Exempt Organizations, § 7.6.

- 42. IRC §§ 170(b)(1)(A)(vi) (IRC § 509(a)(1) and 509(a)(2)). See Private Foundations, Chapter 15.

- 43. See supra notes 26 and 34.

- 44. See § 3.16.

- 45. See § 3.2(a).

- 46. This analysis and the one in § 2.13 were prepared by James M. Greenfield, FAHP, CFRE, author of Fund-Raising: Evaluating and Managing the Fund Development Process, Second Edition (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999), and Fund-Raising Fundamentals: A Guide to Annual Giving for Professionals and Volunteers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994). His contribution is gratefully acknowledged by the authors. The footnotes to §§ 2.2 and 2.13 were added by the authors.

- 47. This statement illustrates how dramatically fundraising (and other) communications have changed in recent years. Other ways a charitable organization can ask for a gift are by means of a website, by email, or by facsimile.

- 48. See § 4.1.

- 49. The increasing sophistication of database companies is allowing them to target mailings more specifically to Americans identified by their racial or ethnic backgrounds; this practice is raising a host of ethical concerns (see, e.g., “The Ethics of ‘Ethnicated’ Mailing Lists,” Wash. Post, Nov. 14, 1992, at A1).

- 50. But see “Evangelists' Electronic Collection Plates Making Fewer Rounds,” Wash. Post, Dec. 20, 1992, at A3.

- 51. In addition, local governments are increasing their regulation of this form of gambling. In general, “Charity Gambling: Who Gets the Take?,” Metro. Times, Aug. 22, 1994, at C4 (The Washington Times); Gattuso, “What's Ahead for Charity Gambling?,” 24 Fund Raising Mgmt. (No. 7) 19 (1993); “Md. Slot Machines Raise Money—and Questions,” Wash. Post, Sept. 27, 1993, at D1; “Charity Casinos Parlayed into Big Business,” Wash. Post, Sept. 26, 1993, at B1; “Charities' Big Gamble” (subtitled “Games of chance raise millions for good works, but questions of fraud could tar nonprofits' image, prompt more regulation”), V Chron. of Phil. (No. 15) 1 (May 18, 1993); “States Say Abuse Is Widespread in Charity Gains,” II Chron. of Phil. (No. 10) 1 (Mar. 6, 1990). One newspaper account stated that “charitable fund-raising [by this method] has lost its innocence. The church basement roulette games that long have been a staple of charitable fund-raising in … [a county near Washington, DC] have grown in recent years into a multi-million-dollar industry that is siphoning money from the people who are supposed to benefit into the pockets of professional gamblers …” (“P.G. Plays Weak Hand against Charity Casinos,” Wash. Post, Feb. 20, 1993, at D1).

- 52. Greenfield, “Fund-Raising Costs and Credibility: What the Public Needs to Know,” NSFRE J., Autumn 1988, at 49.

- 53. Fink and Metzler, The Costs and Benefits of Deferred Giving (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

- 54. For more details about the environmental audit, see Greenfield, “The Fund-Raising Environmental Audit,” 22 Fund Raising Mgmt. (No. 3) 28 (1991).

- 55. For a summary of the role of, compensation of, and demand for the fundraising professional, see “Fund-Raisers' Own Funds Are Rising,” Wall Street J., Mar. 2, 1993, at B1.

- 56. This analysis was prepared by Richard Larkin, CPA, for use as part of this chapter. His contribution is gratefully acknowledged by the authors. Additional information concerning financial management in this context is available in Gross, Jr., Larkin, and McCarthy, Financial and Accounting Guide for Not-for-Profit Organizations (6th ed.; New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

- 57. See § 4.15.

- 58. This commentary is based on an article written by Karl E. Emerson, Director, Bureau of Charitable Organizations, Department of State of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

- 59. This analysis was prepared by Delmar R. Straecker, CFRE. His contribution is gratefully acknowledged by the authors.

- 60. Subsequently, the president of corporate and legal affairs at a fundraising company wrote a letter to the National Association of State Charity Officials, stating, inter alia, “State government officials rob donors by knowingly diverting untold millions of dollars of contributions from their intended purposes under a cumbersome, outdated multistate licensing scheme” and “[t]hey violate clear constitutional [law] precedent, the federal Privacy Act, and even the laws they are charged to enforce as a way to censor and intimidate nonprofit organizations” (Williams, “State Fund-Raising Rules Harm Charities, Critic Says,” XX Chron. of Phil. (No. 1) 32 (Oct. 18, 2007)).

- 61. The balance of this analysis is confined to state laws, but it is equally applicable to a system of local law compliance.

- 62. See Chapter 7.

- 63. See § 4.5.

- 64. See, e.g., § 3.15.

- 65. For the principles an organization may utilize in explanation of the reasonableness of its fundraising costs, see § 4.1.