Chapter 11

Building an Incident Response Program

No matter how well an organization prepares its cybersecurity defenses, the time will come that it suffers a computer security incident that compromises the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information or systems under its control. This incident may be a minor virus infection that is quickly remediated or a serious breach of personal information that comes into the national media spotlight. In either event, the organization must be prepared to conduct a coordinated, methodical response effort. By planning in advance, business leaders, technology leaders, cybersecurity experts, and technologists can decide how they will handle these situations and prepare a well-thought-out response.

Security Incidents

Many IT professionals use the terms security event and security incident casually and interchangeably, but this is not correct. Members of a cybersecurity incident response team should use these terms carefully and according to their precise definitions within the organization. The National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) offers the following standard definitions for use throughout the U.S. government, and many private organizations choose to adopt them as well:

- An event is any observable occurrence in a system or network. A security event includes any observable occurrence that relates to a security function. For example, a user accessing a file stored on a server, an administrator changing permissions on a shared folder, and an attacker conducting a port scan are all examples of security events.

- An adverse event is any event that has negative consequences. Examples of adverse events include a malware infection on a system, a server crash, and a user accessing a file that they are not authorized to view.

- A security incident is a violation or imminent threat of violation of computer security policies, acceptable use policies, or standard security practices. Examples of security incidents include the accidental loss of sensitive information, an intrusion into a computer system by an attacker, the use of a keylogger on an executive's system to steal passwords, and the launch of a denial-of-service attack against a website.

Computer security incident response teams (CSIRTs) are responsible for responding to computer security incidents that occur within an organization by following standardized response procedures and incorporating their subject matter expertise and professional judgment.

For brevity's sake, we will use the term incident as shorthand for computer security incident in the remainder of this book.

Phases of Incident Response

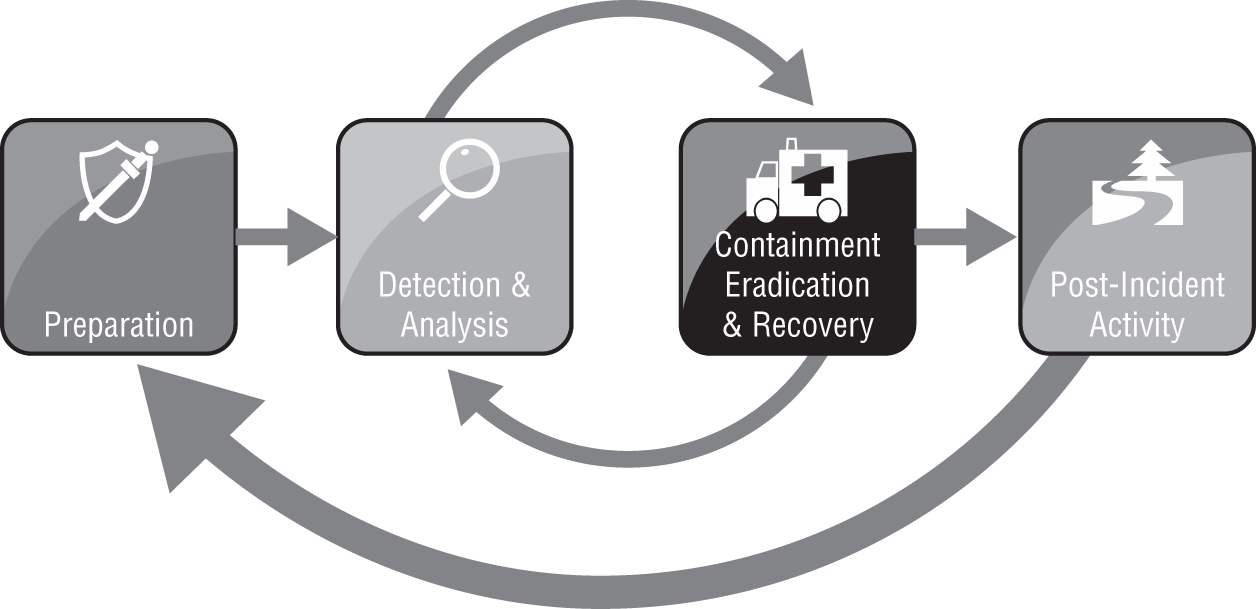

Organizations depend on members of the CSIRT to respond calmly and consistently in the event of a security incident. The crisis-like atmosphere that surrounds many security incidents may lead to poor decision making unless the organization has a clearly thought-out and refined process that describes how it will handle cybersecurity incident response. Figure 11.1 shows the simple incident response process advocated by NIST.

FIGURE 11.1 Incident response process

Source: NIST SP 800-61: Computer Security Incident Handling Guide

Notice that this process is not a simple progression of steps from start to finish. Instead, it includes loops that allow responders to return to prior phases as needed during the response. These loops reflect the reality of responses to actual cybersecurity incidents. Only in the simplest of incidents would an organization detect an incident, analyze data, conduct a recovery, and close out the incident in a straightforward sequence of steps. Instead, the containment process often includes several loops back through the detection and analysis phase to identify whether the incident has been successfully resolved. These loops are a normal part of the cybersecurity incident response process and should be expected.

Preparation

CSIRTs do not spring up out of thin air. As much as managers may wish it were so, they cannot simply will a CSIRT into existence by creating a policy document and assigning staff members to the CSIRT. Instead, the CSIRT requires careful preparation to ensure that the CSIRT has the proper policy foundation, has operating procedures that will be effective in the organization's computing environment, receives appropriate training, and is prepared to respond to an incident.

The next two sections of this chapter, “Building the Foundation for Incident Response” and “Creating an Incident Response Team,” describe the preparation phase in greater detail.

The preparation phase also includes building strong cybersecurity defenses to reduce the likelihood and impact of future incidents. This process of building a defense-in-depth approach to cybersecurity often includes many personnel who might not be part of the CSIRT.

During the preparation phase, the organization should also assemble the hardware, software, and information required to conduct an incident investigation. NIST recommends that every organization's incident response toolkit should include, at a minimum, the following:

- Digital forensic workstations

- Backup devices

- Laptops for data collection, analysis, and reporting

- Spare server and networking equipment

- Blank removable media

- Portable printer

- Forensic and packet capture software

- Bootable USB media containing trusted copies of forensic tools

- Office supplies and evidence collection materials

You'll learn more about the tools used to conduct the incident response process in Chapters 12, 13, and 14.

Detection and Analysis

The detection and analysis phase of incident response is one of the trickiest to commit to a routine process. Although cybersecurity analysts have many tools at their disposal that may assist in identifying that a security incident is taking place, many incidents are only detected because of the trained eye of an experienced analyst.

NIST 800-61 describes four major categories of security event indicators:

- Alerts that originate from intrusion detection and prevention systems, security information and event management systems, antivirus software, file integrity checking software, and/or third-party monitoring services

- Logs generated by operating systems, services, applications, network devices, and network flows

- Publicly available information about new vulnerabilities and exploits detected “in the wild” or in a controlled laboratory environment

- People from inside the organization or external sources who report suspicious activity that may indicate a security incident is in progress

When any of these information sources indicate that a security incident may be occurring, cybersecurity analysts should shift into the initial validation mode, where they attempt to determine whether an incident is taking place that merits further activation of the incident response process. This analysis is often more art than science and is very difficult work. NIST recommends the following actions to improve the effectiveness of incident analysis:

- Profile networks and systems to measure the characteristics of expected activity. This will improve the organization's ability to identify abnormal activity during the detection and analysis process.

- Understand normal behavior of users, systems, networks, and applications. This behavior will vary between organizations, at different times of the day, week, and year and with changes in the business cycle. A solid understanding of normal behavior is critical to recognizing deviations from those patterns.

- Create a logging policy that specifies the information that must be logged by systems, applications, and network devices. The policy should also specify where those log records should be stored (preferably in a centralized log management system) and the retention period for logs.

- Perform event correlation to combine information from multiple sources. This function is typically performed by a security information and event management (SIEM) system.

- Synchronize clocks across servers, workstations, and network devices. This is done to facilitate the correlation of log entries from different systems. Organizations may easily achieve this objective by operating a Network Time Protocol (NTP) server.

- Maintain an organizationwide knowledge base that contains critical information about systems and applications. This knowledge base should include information about system profiles, usage patterns, and other information that may be useful to responders who are not familiar with the inner workings of a system.

- Capture network traffic as soon as an incident is suspected. If the organization does not routinely capture network traffic, responders should immediately begin packet captures during the detection and analysis phase. This information may provide critical details about an attacker's intentions and activity.

- Filter information to reduce clutter. Incident investigations generate massive amounts of information, and it is basically impossible to interpret it all without both inclusion and exclusion filters. Incident response teams may wish to create some predefined filters during the preparation phase to assist with future analysis efforts.

- Seek assistance from external resources. Responders should know the parameters for involving outside sources in their response efforts. This may be as simple as conducting a Google search for a strange error message, or it may involve full-fledged coordination with other response teams.

You'll learn more about the process of detecting and analyzing a security incident in Chapter 12, “Analyzing Indicators of Compromise.”

Containment, Eradication, and Recovery

During the incident detection and analysis phase, the CSIRT engages in primarily passive activities designed to uncover and analyze information about the incident. After completing this assessment, the team moves on to take active measures designed to contain the effects of the incident, eradicate the incident from the network, and recover normal operations.

At a high level, the containment, eradication, and recovery phase of the process is designed to achieve these objectives:

- Select a containment strategy appropriate to the incident circumstances.

- Implement the selected containment strategy to limit the damage caused by the incident.

- Gather additional evidence as needed to support the response effort and potential legal action.

- Identify the attackers and attacking systems.

- Eradicate the effects of the incident and recover normal business operations.

You'll learn more about the techniques used during the containment, eradication, and recovery phase of incident response in Chapter 14, “Containment, Eradication, and Recovery.”

Postincident Activity

Security incidents don't end after security professionals remove attackers from the network or complete the recovery effort to restore normal business operations. Once the immediate danger passes and normal operations resume, the CSIRT enters the postincident activity phase of incident response. During this phase, team members conduct a lessons learned review and ensure that they meet internal and external evidence retention requirements.

Lessons Learned Review

During the lessons learned review, responders conduct a thorough review of the incident and their response, with an eye toward improving procedures and tools for the next incident. This review is most effective if conducted during a meeting where everyone is present for the discussion (physically or virtually). Although some organizations try to conduct lessons learned reviews in an offline manner, this approach does not lead to the back-and-forth discussion that often yields the greatest insight.

The lessons learned review should be facilitated by an independent facilitator who was not involved in the incident response and is perceived by everyone involved as an objective outsider. This allows the facilitator to guide the discussion in a productive manner without participants feeling that the facilitator is advancing a hidden agenda. NIST recommends that lessons learned processes answer the following questions:

- Exactly what happened and at what times?

- How well did staff and management perform in responding to the incident?

- Were the documented procedures followed? Were they adequate?

- What information was needed sooner?

- Were any steps or actions taken that might have inhibited the recovery?

- What would the staff and management do differently the next time a similar incident occurs?

- How could information sharing with other organizations have been improved?

- What corrective actions can prevent similar incidents in the future?

- What precursors or indicators should be watched for in the future to detect similar incidents?

- What additional tools or resources are needed to detect, analyze, and mitigate future incidents?

Once the group answers these questions, management must ensure that the organization takes follow-up actions, as appropriate. Lessons learned reviews are only effective if they surface needed changes and those changes then occur to improve future incident response efforts.

Evidence Retention

At the conclusion of an incident, the CSIRT has often gathered large quantities of evidence. The team leader should work with staff to identify both internal and external evidence retention requirements. If the incident may result in civil litigation or criminal prosecution, the team should consult attorneys prior to discarding any evidence. If there is no likelihood that the evidence will be used in court, the team should follow any retention policies that the organization has in place.

At the conclusion of the postincident activity phase, the CSIRT deactivates, and the incident-handling cycle returns to the preparation, detect, and analyze phases.

You'll read more about the activities undertaken during the postincident activity phase in Chapter 14.

Building the Foundation for Incident Response

One of the major responsibilities that organizations have during the preparation phase of incident response is building a solid policy and procedure foundation for the program. This creates the documentation required to support the program's ongoing efforts.

Policy

The incident response policy serves as the cornerstone of an organization's incident response program. This policy should be written to guide efforts at a high level and provide the authority for incident response. The policy should be approved at the highest level possible within the organization, preferably by the chief executive officer. For this reason, policy authors should attempt to write the policy in a manner that makes it relatively timeless. This means that the policy should contain statements that provide authority for incident response, assign responsibility to the CSIRT, and describe the role of individual users and state organizational priorities. The policy is not the place to describe specific technologies, response procedures, or evidence-gathering techniques. Those details may change frequently and should be covered in more easily changed procedure documents.

NIST recommends that incident response policies contain these key elements:

- Statement of management commitment

- Purpose and objectives of the policy

- Scope of the policy (to whom it applies and under what circumstances)

- Definition of cybersecurity incidents and related terms

- Organizational structure and definition of roles, responsibilities, and level of authority

- Prioritization or severity rating scheme for incidents

- Performance measures for the CSIRT

- Reporting and contact forms

Including these elements in the policy provides a solid foundation for the CSIRT's routine and crisis activities.

Procedures and Playbooks

Procedures provide the detailed, tactical information that CSIRT members need when responding to an incident. They represent the collective wisdom of team members and subject matter experts collected during periods of calm and are ready to be applied in the event of an actual incident. CSIRT teams often develop playbooks that describe the specific procedures that they will follow in the event of a specific type of cybersecurity incident. For example, a financial institution CSIRT might develop playbooks that cover

- Breach of personal financial information

- Web server defacement

- Phishing attack targeted at customers

- Loss of a laptop

- General security incident not covered by another playbook

This is clearly not an exhaustive list, and each organization will develop playbooks that describe their response to both high severity and frequently occurring incident categories. The idea behind the playbook is that the team should be able to pick it up and find an operational plan for responding to the security incident that they may follow. Playbooks are especially important in the early hours of incident response to ensure that the team has a planned, measured response to the first reports of a potential incident.

Documenting the Incident Response Plan

When developing the incident response plan documentation, organizations should pay particular attention to creating tools that may be useful during an incident response. These tools should provide clear guidance to response teams that may be quickly read and interpreted during a crisis situation. For example, the incident response checklist shown in Figure 11.2 provides a high-level overview of the incident response process in checklist form. The CSIRT leader may use this checklist to ensure that the team doesn't miss an important step in the heat of the crisis environment.

FIGURE 11.2 Incident response checklist

Source: NIST SP 800-61: Computer Security Incident Handling Guide

Creating an Incident Response Team

There are many different roles that should be represented on a CSIRT. Depending on the organization and its technical needs, some of these roles may be core team members who are always activated, whereas others may be called in as needed on an incident-by-incident basis. For example, a database administrator might be crucial when investigating the aftermath of a SQL injection attack but would probably not be very helpful when responding to a stolen laptop.

The core incident response team normally consists of cybersecurity professionals with specific expertise in incident response. In larger organizations, these may be full-time employees dedicated to incident response, whereas smaller organizations may call on cybersecurity experts who fill other roles for their “day jobs” to step into CSIRT roles in the aftermath of an incident.

In addition to the core team members, the CSIRT may include representation from the following:

- Technical subject matter experts whose knowledge may be required during a response. This includes system engineers, network administrators, database administrators, desktop experts, and application experts.

- IT support staff who may be needed to carry out actions directed by the CSIRT.

- Legal counsel responsible for ensuring that the team's actions comply with legal, policy, and regulatory requirements and can advise team leaders on compliance issues and communication with regulatory bodies.

- Human resources staff responsible for investigating potential employee malfeasance.

- Public relations and marketing staff who can coordinate communications with the media and general public.

The CSIRT should be run by a designated leader with the clear authority to direct incident response efforts and serve as a liaison to management. This leader should be a skilled incident responder who is either assigned to lead the CSIRT as a full-time responsibility or serves in a cybersecurity leadership position.

Incident Response Providers

In addition to including internal team members on the CSIRT, the organization may decide to outsource some or all of their actions to an incident response provider. Retaining an incident response provider gives the organization access to expertise that might not otherwise exist inside the firm. This may come at significant expense, so the organizations should decide what types of incidents may be handled internally and which justify the use of an outside provider. Additionally, the organization should understand the provider's guaranteed response time and ensure that it has a plan in place to respond to the early stages of an incident before the provider assumes control.

CSIRT Scope of Control

The organization's incident response policy should clearly outline the scope of the CSIRT. This includes answers to the following questions:

- What triggers the activation of the CSIRT? Who is authorized to activate the CSIRT?

- Does the CSIRT cover the entire organization or is it responsible only for certain business units, information categories, or other divisions of responsibility?

- Is the CSIRT authorized to communicate with law enforcement, regulatory bodies, or other external parties and, if so, which ones?

- Does the CSIRT have internal communication and/or escalation responsibilities? If so, what triggers those requirements?

Coordination and Information Sharing

During an incident response effort, CSIRT team members often need to communicate and share information with both internal and external partners. Smooth information sharing is essential to an effective and efficient incident response, but it must be done within the clearly established parameters of an incident communication plan. The organization's incident response policies should limit communication to trusted parties and put controls in place to prevent the inadvertent release of sensitive information outside of those trusted partners.

Internal Communications

Internal communications among the CSIRT and with other employees within the organization should take place over secure communications channels that are designated in advance and tested for security. This may include email, instant messaging, message boards, and other collaboration tools that pass security muster. The key is to evaluate and standardize those communications tools in advance so that responders are not left to their own devices to identify tools in the heat of an incident.

External Communications

CSIRT team members, business leaders, public relations teams, and legal counsel may all bring to the table requirements that may justify sharing limited or detailed information with external entities. The incident response plan should guide these efforts. Types of external communications may include the following:

- Law enforcement may wish to be involved when a cybersecurity incident appears to be criminal in nature. The organization may choose to cooperate or decline participation in an investigation but should always make this decision with the advice of legal counsel.

- Information sharing partners, such as the Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC), provide community-based warnings of cybersecurity risks. The organization may choose to participate in one of these consortiums and, in some cases, share information about ongoing and past security incidents to partners in that consortium.

- Vendors may be able to provide information crucial to the response. The manufacturers of hardware and software used within the organization may be able to provide patches, troubleshooting advice, or other guidance crucial to the response effort.

- Other organizations may be actual or potential victims of the same attack. CSIRT members may wish to coordinate their incident response with other organizations.

- Communications with the media and the general public may be mandatory under regulatory or legislative reporting requirements, voluntary, or forced by media coverage of a security incident.

It is incumbent upon the CSIRT leader to control and coordinate external communications in a manner that meets regulatory requirements and best serves the response effort.

Classifying Incidents

Each time an incident occurs, the CSIRT should classify the incident by both the type of threat and the severity of the incident according to a standardized incident severity rating system. This classification aids other personnel in understanding the nature and severity of the incident and allows the comparison of the current incident to past and future incidents.

Threat Classification

In many cases, the incident will come from a known threat source that facilitates the rapid identification of the threat. NIST provides the following attack vectors that are useful for classifying threats:

- External/Removable Media An attack executed from removable media or a peripheral device—for example, malicious code spreading onto a system from an infected USB flash drive.

- Attrition An attack that employs brute-force methods to compromise, degrade, or destroy systems, networks, or services—for example, a DDoS attack intended to impair or deny access to a service or application or a brute-force attack against an authentication mechanism.

- Web An attack executed from a website or web-based application—for example, a cross-site scripting attack used to steal credentials or redirect to a site that exploits a browser vulnerability and installs malware.

- Email An attack executed via an email message or attachment—for example, exploit code disguised as an attached document or a link to a malicious website in the body of an email message.

- Impersonation An attack involving replacement of something benign with something malicious—for example, spoofing, man-in-the-middle attacks, rogue wireless access points, and SQL injection attacks all involve impersonation.

- Improper Usage Any incident resulting from violation of an organization's acceptable usage policies by an authorized user, excluding the previous categories; for example, a user installs file-sharing software, leading to the loss of sensitive data, or a user performs illegal activities on a system.

- Loss or Theft of Equipment The loss or theft of a computing device or media used by the organization, such as a laptop, smartphone, or authentication token.

- Unknown An attack of unknown origin.

- Other An attack of known origin that does not fit into any of the previous categories.

In addition to understanding these attack vectors, cybersecurity analysts should be familiar with the concept of an advanced persistent threat (APT). APT attackers are highly skilled and talented attackers focused on a specific objective. These attackers are often funded by nation-states, organized crime, and other sources with tremendous resources. APT attackers are known for taking advantage of zero-day vulnerabilities—vulnerabilities that are unknown to the security community and, as a result, are not included in security tests performed by vulnerability scanners and other tools and have no patches available to correct them.

Severity Classification

CSIRT members may investigate dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of security incidents each year, depending on the scope of their responsibilities and the size of the organization. Therefore, it is important to use a standardized process to communicate the severity of each incident to management and other stakeholders. Incident severity information assists in the prioritization and scope of incident response efforts.

Two key measures used to determine the incident severity are the scope of the impact and the types of data involved in the incident.

Scope of Impact

The scope of an incident's impact depends on the degree of impairment that it causes the organization as well as the effort required to recover from the incident.

Functional Impact

The functional impact of an incident is the degree of impairment that it causes to the organization. This may vary based on the criticality of the data, systems or processes affected by the incident, as well as the organization's ability to continue providing services to users as an incident unfolds and in the aftermath of the incident. NIST recommends using four categories to describe the functional impact of an incident, as shown in Table 11.1.

TABLE 11.1 NIST functional impact categories

Source: NIST SP 800-61

| Category | Definition |

| None | No effect to the organization's ability to provide all services to all users. |

| Low | Minimal effect; the organization can still provide all critical services to all users but has lost efficiency. |

| Medium | The organization has lost the ability to provide a critical service to a subset of system users. |

| High | The organization is no longer able to provide some critical services to any users. |

There is one major gap in the functional impact assessment criteria provided by NIST: it does not include any assessment of the economic impact of a security incident on the organization. This may be because the NIST guidelines are primarily intended to serve a government audience. Organizations may wish to modify the categories in Table 11.1 to incorporate economic impact or measure financial impact using a separate scale, such as the one shown in Table 11.2.

TABLE 11.2 Economic impact categories

| Category | Definition |

| None | The organization does not expect to experience any financial impact or the financial impact is negligible. |

| Low | The organization expects to experience a financial impact of $10,000 or less. |

| Medium | The organization expects to experience a financial impact of more than $10,000 but less than $500,000. |

| High | The organization expects to experience a financial impact of $500,000 or more. |

The financial thresholds included in Table 11.2 are intended as examples only and should be adjusted according to the size of the organization. For example, a security incident causing a $500,000 loss may be crippling for a small business, whereas a Fortune 500 company may easily absorb this loss.

Recoverability Effort

In addition to measuring the functional and economic impact of a security incident, organizations should measure the time that services will be unavailable. This may be expressed as a function of the amount of downtime experienced by the service or the time required to recover from the incident. Table 11.3 shows the recommendations suggested by NIST for assessing the recoverability impact of a security incident.

Datatypes

The nature of the data involved in a security incident also contributes to the incident severity. When a security incident affects the confidentiality or integrity of sensitive information, cybersecurity analysts should assign a data impact rating. The data impact rating scale recommended by NIST appears in Table 11.4.

TABLE 11.3 NIST recoverability effort categories

Source: NIST SP 800-61

| Category | Definition |

| Regular | Time to recovery is predictable with existing resources. |

| Supplemented | Time to recovery is predictable with additional resources. |

| Extended | Time to recovery is unpredictable; additional resources and outside help are needed. |

| Not Recoverable | Recovery from the incident is not possible (e.g., sensitive data exfiltrated and posted publicly); launch investigation. |

Although the impact scale presented in Table 11.4 is NIST's recommendation, it does have some significant shortcomings. Most notably, the definitions included in the table are skewed toward the types of information that might be possessed by a government agency and might not map well to information in the possession of a private organization. Some analysts might also object to the inclusion of “integrity loss” as a single category separate from the three classification-dependent breach categories.

TABLE 11.4 NIST information impact categories

Source: NIST SP 800-61

| Category | Definition |

| None | No information was exfiltrated, changed, deleted, or otherwise compromised. |

| Privacy breach | Sensitive personally identifiable information (PII) of taxpayers, employees, beneficiaries, and so on was accessed or exfiltrated. |

| Proprietary breach | Unclassified proprietary information, such as protected critical infrastructure information (PCII) was accessed or exfiltrated. |

| Integrity loss | Sensitive or proprietary information was changed or deleted. |

Table 11.5 presents an alternative classification scheme that private organizations might use as the basis for their own information impact categorization schemes.

TABLE 11.5 Private organization information impact categories

| Category | Definition |

| None | No information was exfiltrated, changed, deleted, or otherwise compromised. |

| Regulated information breach | Information regulated by an external compliance obligation was accessed or exfiltrated. This may include personally identifiable information (PII) that triggers a data breach notification law, protected health information (PHI) under HIPAA, and/or payment card information protected under PCI DSS. For organizations subject to the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), it should also include sensitive personal information (SPI) as defined under GDPR. SPI includes information from special categories, such as genetic data, trade union membership, and sexual information. |

| Intellectual property breach | Sensitive intellectual property was accessed or exfiltrated. This may include product development plans, formulas, or other sensitive trade secrets. |

| Confidential information breach | Corporate confidential information was accessed or exfiltrated. This includes information that is sensitive or classified as a high-value asset but does not fit under the categories of regulated information or intellectual property. Examples might include corporate financial information or information about mergers and acquisitions. |

| Integrity loss | Sensitive or proprietary information was changed or deleted. |

As with the financial impact scale, organizations will need to customize the information impact categories in Table 11.5 to meet the unique requirements of their business processes.

Summary

Incident response programs provide organizations with the ability to respond to security issues in a calm, repeatable manner. Security incidents occur when there is a known or suspected violation or imminent violation of an organization's security policies. When a security incident occurs, the organization should activate its computer security incident response team (CSIRT).

The CSIRT guides the organization through the four stages of incident response: preparation; detection and analysis; containment, eradication, and recovery; and postincident activities. During the preparation phase, the organization ensures that the CSIRT has the proper policy foundation, has operating procedures that will be effective in the organization's computing environment, receives appropriate training, and is prepared to respond to an incident.

During the detection and analysis phase, the organization watches for signs of security incidents. This includes monitoring alerts, logs, publicly available information, and reports from internal and external staff about security anomalies. When the organization suspects a security incident, it moves into the containment, eradication, and recovery phase, which is designed to limit the damage and restore normal operations as quickly as possible.

Restoration of normal activity doesn't signal the end of incident response efforts. At the conclusion of an incident, the postincident activities phase provides the organization with the opportunity to reflect upon the incident by conducting a lessons learned review. During this phase, the organization should also ensure that evidence is retained for future use according to policy.

Exam Essentials

Distinguish between security events and security incidents. An event is any observable occurrence in a system or network. A security event includes any observable occurrence that relates to a security function. A security incident is a violation or imminent threat of violation of computer security policies, acceptable use policies, or standard security practices. Every incident consists of one or more events, but every event is not an incident.

Name the four phases of the cybersecurity incident response process. The four phases of incident response are preparation; detection and analysis; containment, eradication, and recovery; and postincident activities. The process is not a simple progression of steps from start to finish. Instead, it includes loops that allow responders to return to prior phases as needed during the response.

Identify security event indicators. Alerts originate from intrusion detection and prevention systems, security information and event management systems, antivirus software, file integrity checking software, and third-party monitoring services. Logs are generated by operating systems, services, applications, network devices, and network flows. Publicly available information exists about new vulnerabilities and exploits detected “in the wild” or in a controlled laboratory environment. People from inside the organization or external sources report suspicious activity that may indicate that a security incident is in progress.

Explain how policies, procedures, and playbooks guide incident response efforts. The incident response policy serves as the cornerstone of an organization's incident response program. This policy should be written to guide efforts at a high level and provide the authority for incident response. Procedures provide the detailed, tactical information that CSIRT members need when responding to an incident. CSIRT teams often develop playbooks that describe the specific procedures that they will follow in the event of a specific type of cybersecurity incident.

Know that incident response teams should represent diverse stakeholders. The core incident response team normally consists of cybersecurity professionals with specific expertise in incident response. In addition to the core team members, the CSIRT may include representation from technical subject matter experts, IT support staff, legal counsel, human resources staff, and public relations and marketing teams. The team will also need to coordinate with internal and external stakeholders, including senior leadership, law enforcement, and regulatory bodies.

Explain how incidents can be classified according to the attack vector where they originate. Common attack vectors for security incidents include external/removable media, attrition, the web, email, impersonation, improper usage, loss or theft of equipment, and other/unknown sources.

Explain how response teams classify the severity of an incident. The functional impact of an incident is the degree of impairment that it causes to the organization. The economic impact is the amount of financial loss that the organization incurs. In addition to measuring the functional and economic impact of a security incident, organizations should measure the time that services will be unavailable and the recoverability effort. Finally, the nature of the data involved in an incident also contributes to the severity as the information impact.

Lab Exercises

Activity 11.1: Incident Severity Classification

You are the leader of cybersecurity incident response team for a large company that is experiencing a denial-of-service attack on its website. This attack is preventing the organization from selling products to its customers and is likely to cause lost revenue of at least $2 million per day until the incident is resolved.

The attack is coming from many different sources, and you have exhausted all of the response techniques at your disposal. You are currently looking to identify an external partner that can help with the response.

Classify this incident using the criteria described in this chapter. Assign categorical ratings for functional impact, economic impact, recoverability effort, and information impact. Justify each of your assignments.

Activity 11.2: Incident Response Phases

Identify the correct phase of the incident response process that corresponds to each of the following activities:

| Activity | Phase |

| Conducting a lessons learned review session | |

| Receiving a report from a staff member about a malware infection | |

| Upgrading the organization's firewall to block a new type of attack | |

| Recovering normal operations after eradicating an incident | |

| Identifying the attackers and attacking systems | |

| Interpreting log entries using a SIEM to identify a potential incident | |

| Assembling the hardware and software required to conduct an incident investigation |

Activity 11.3: Develop an Incident Communications Plan

You are the CSIRT leader for a major e-commerce website, and you are currently responding to a security incident where you believe attackers used a SQL injection attack to steal transaction records from your backend database.

Currently, only the core CSIRT members are responding. Develop a communication plan that describes the nature, timing, and audiences for communications to the internal and external stakeholders that you believe need to be notified.

Review Questions

- Which one of the following is an example of a computer security incident?

- User accesses a secure file

- Administrator changes a file's permission settings

- Intruder breaks into a building

- Former employee crashes a server

- During what phase of the incident response process would an organization implement defenses designed to reduce the likelihood of a security incident?

- Preparation

- Detection and analysis

- Containment, eradication, and recovery

- Postincident activity

- Alan is responsible for developing his organization's detection and analysis capabilities. He would like to purchase a system that can combine log records from multiple sources to detect potential security incidents. What type of system is best suited to meet Alan's security objective?

- IPS

- IDS

- SIEM

- Firewall

- Ben is working to classify the functional impact of an incident. The incident has disabled email service for approximately 30 percent of his organization's staff. How should Ben classify the functional impact of this incident according to the NIST scale?

- None

- Low

- Medium

- High

- What phase of the incident response process would include measures designed to limit the damage caused by an ongoing breach?

- Preparation

- Detection and analysis

- Containment, eradication, and recovery

- Postincident activity

- Grace is the CSIRT team leader for a business unit within NASA, a federal agency. What is the minimum amount of time that Grace must retain incident handling records?

- Six months

- One year

- Two years

- Three years

- Karen is responding to a security incident that resulted from an intruder stealing files from a government agency. Those files contained unencrypted information about protected critical infrastructure. How should Karen rate the information impact of this loss?

- None

- Privacy breach

- Proprietary breach

- Integrity loss

- Matt is concerned about the fact that log records from his organization contain conflicting timestamps due to unsynchronized clocks. What protocol can he use to synchronize clocks throughout the enterprise?

- NTP

- FTP

- ARP

- SSH

- Which one of the following document types would outline the authority of a CSIRT responding to a security incident?

- Policy

- Procedure

- Playbook

- Baseline

- A cross-site scripting attack is an example of what type of threat vector?

- Impersonation

- Attrition

- Web

- Which one of the following parties is not commonly the target of external communications during an incident?

- The perpetrator

- Law enforcement

- Vendors

- Information sharing partners

- Robert is finishing a draft of a proposed incident response policy for his organization. Who would be the most appropriate person to sign the policy?

- CEO

- Director of security

- CIO

- CSIRT leader

- Which one of the following is not an objective of the containment, eradication, and recovery phase of incident response?

- Detect an incident in progress

- Implement a containment strategy

- Identify the attackers

- Eradicate the effects of the incident

- Renee is responding to a security incident that resulted in the unavailability of a website critical to her company's operations. She is unsure of the amount of time and effort that it will take to recover the website. How should Renee classify the recoverability effort?

- Regular

- Supplemented

- Extended

- Not recoverable

- Which one of the following is an example of an attrition attack?

- SQL injection

- Theft of a laptop

- User installs file sharing software

- Brute-force password attack

- Who is the best facilitator for a postincident lessons learned session?

- CEO

- CSIRT leader

- Independent facilitator

- First responder

- Which one of the following elements is not normally found in an incident response policy?

- Performance measures for the CSIRT

- Definition of cybersecurity incidents

- Definition of roles, responsibilities, and levels of authority

- Procedures for rebuilding systems

- A man-in-the-middle attack is an example of what type of threat vector?

- Attrition

- Impersonation

- Web

- Tommy is the CSIRT team leader for his organization and is responding to a newly discovered security incident. What document is most likely to contain step-by-step instructions that he might follow in the early hours of the response effort?

- Policy

- Baseline

- Playbook

- Textbook

- Hank is responding to a security event where the CEO of his company had her laptop stolen. The laptop was encrypted but contained sensitive information about the company's employees. How should Hank classify the information impact of this security event?

- None

- Privacy breach

- Proprietary breach

- Integrity loss