Chapter 15

BANK REGULATORY CAPITAL, BASEL RULES AND ICAAP

A bank's strategy is closely linked to its capital position. That said, a bank's capital position also drives its strategy. Like all commercial enterprises, the return shareholders receive for their investment in a bank or financial holding company is of critical importance when considering the value generated. Furthermore, the regulators and society in general require banks to be well capitalised to reduce friction to the financial system. Well‐regulated and strongly capitalised banks are fundamental to a robust financial system.

Bank capital is a concept that is central to the understanding, and management, of a bank's business strategy and the risk exposure associated with that strategy. In the business media, it is often suggested that capital is the most important aspect of bank risk management, but although such a view is not wholly correct (liquidity and funding are as important certainly, if not more so), it is indeed the case that effective capital management is essential if a bank is to continue to deliver shareholder returns through the economic cycle. Put simply, understanding capital is key to understanding what banks do, the risks they take, and how best these risks should be managed.

Often capital is spoken of as being “held” or “put aside” by a bank in order to support lending operations, as if it was some kind of asset. This is an unfortunate turn of phrase. Far from being an asset, capital is a liability, alongside all the other forms of liability the bank has, and as such a form of funding for the bank. However, unlike the other forms of liability it has no fixed interest cost, indeed given that core capital is not obliged to pay out any form of coupon at any time it has no explicit interest cost. Moreover, because it has no repayment date it is able to absorb losses. Such losses could otherwise threaten a bank's solvency, so it is easy to see why a sufficient capital base to cover all eventualities is essential for every bank. Alternative sources of “non‐core Tier 1” capital with contractual costs and different levels of loss absorption are also available to banks. In this chapter, the core issues of capital management from both a bank governance viewpoint as well as the regulatory requirement viewpoint are discussed. Then the issues surrounding the delivery and presentation of the internal capital adequacy assessment process, or ICAAP, and stress testing issues associated with the ICAAP are presented.

THE BANKING MODEL AND CAPITAL

This chapter describes the best‐practice framework within which capital should be planned and managed within a bank, including the internal processes undertaken to ensure regulatory compliance (perhaps best exemplified by the “ICAAP” process, which is covered later in the chapter). Before that, however, the concepts of capital and its purpose are introduced. The best‐practice recommended approach to use of capital is also presented.

The business model and capital

The importance of capital to a bank and an appropriate appreciation of its importance requires a genuine understanding of what banks actually do. In essence they:

- Provide transaction services for customers, primarily payments, which enable them to settle commercial transactions;

- Provide funding, in the form of credit, to customers to enable them to enter into commercial transactions; and

- Provide risk management services to customers, ranging from the simple current account (“checking account”) to more complex services that enable customers to manage and hedge their foreign exchange and interest‐rate risk exposures.

Services 2 and 3 require a bank to undertake two fundamentally contradictory things: lend money for as long a period as the customer requires, and accept deposits on an “instant access” basis from customers. This is the process of “maturity transformation”, the very definition of the banking business model, and it is the risk exposures generated by operating this model that make capital and liquidity so important for a bank. Liquidity was covered in Chapters 10 and 11.

A stylised bank balance sheet is shown in Figure 15.1.

Figure 15.1 Stylised representation of a typical commercial bank balance sheet

Bank balance sheet

The balance sheet is a snapshot in time of the bank's financial strength. Note that the capital amount must, at all times, be more than sufficient to absorb customer loan losses (or losses incurred for other reasons, such as the result of proprietary trading losses or ineffective hedging resulting in unexpected losses). However, the reality of government regulation, which every bank in the world is subject to, means that banks don't need sufficient capital to absorb only losses. They also need sufficient capital to absorb losses and still, after such absorption, be able to demonstrate capital levels that are above the regulatory minimum. Banking is all about confidence. If customers have confidence in the bank, they will continue to place their funds on deposit there. If they do not, they will not. A bank that dips below its regulatory minimum capital ratios, even if it has still absorbed all its losses to date, will not be able to maintain that confidence.

In other words, good capital management, and indeed considered by some practitioners as best‐practice capital management, is all about managing capital on a going concern basis. The Board of a bank takes responsibility to articulate its risk appetite such that this requirement is met. It is generally considered bad practice to manage capital on a gone concern basis. The available capital, the actual amount that can be used to absorb losses, is the surplus above the minimum required by the regulator. Capital that meets the regulator's requirement is not, in truth, available to absorb losses on a going concern basis. It is essential that bank Boards and executive directors manage the institution on this basis.

Invariably banks may fail. In such circumstances the capital sources must be adequate to recover the bank or, if this is not possible, resolve the bank without undue stress to the financial system. This, however, is more feasible in theory than in practice. If a bank fails, one can assume, to a reasonable and safe extent, that its capital base will be insufficient to recover it, and for large banks to resolve it either.

Treatment of bank capital

The core Tier 1 capital base of a bank comprises its initial capital, or start‐up capital, and retained earnings that have been placed in the reserves. Generally, the simplest and most transparent model is to consider that the complete capital base is used as part of a leveraged business model in which it represents equity backing for borrowed funds, which are invested in assets. The return on the assets covers for the cost of borrowing, and the surplus over this and all other costs is the shareholder value‐added for the equity owner.

In its simplest form, the bank's capital should not be exposed to risk. Ideally, it must be placed in an instantly liquid risk‐free asset, with zero counterparty risk, so that it itself is not in danger of erosion and can be retrieved easily if needed, either to cover losses or to fund further expansion and investment. The only assets that fit this category are a deposit at the central bank or an investment in the sovereign bonds of the same currency. All other investments carry an element of counterparty and/or liquidity risk and may be considered unsuitable assets in which to invest the bank's capital.

The logic is straightforward: given that capital available must be sufficient to cover unexpected losses, as well as expected losses, if the capital itself was placed at risk, then there would be no guarantee that it would be able to absorb all losses at any one time. A loss elsewhere in the portfolio may occur at the same time as losses from assets that were funded with capital. This is what is meant when managing capital on a going concern basis is referred to.

The equity and funding provide the sources of funding to invest in assets. The bank has to hold sufficient liquid assets and cash to ensure liquidity pressures can be met immediately. Given that capital is generally only returned through dividends, the capital therefore has a very long behavioural term. The Treasury of the bank acts as the “bank to the bank”, that is, to provide funding to all assets and pay for all liabilities. From an accounting perspective, the cost of funding of capital is nil. An endowment benefit therefore arises as no expense is incurred for this funding. In order to ensure that businesses in a bank group do not unduly benefit from such capital structures, the central Treasury charges a funding cost on all assets and pays a funding cost to all liabilities, including capital.

So the capital base itself should not be expected to generate a return. Where it does, for example, the coupon return from a holding of government bonds, this income on capital should accrue to a central book or asset–liability committee “ALCO” book, and not to any business line. Neither is it allocated on a pro‐rata basis to the business lines, otherwise the calculation of shareholder value‐added by the businesses will be skewed. The business lines are assumed to utilise matched funding instruments to fund their operations. Certain banks also charge a capital risk premium, which will also accrue to the “ALCO” book. Views vary on the treatment of this endowment benefit. Some banks keep the benefit in the ALCO book and implement an economic profit type of management account framework, while others allocate some or all of the benefit to incentivise business, hence there is no cost to allocate.

The target return on equity, set by the shareholder and therefore the Board as their representatives, sets the hurdle rate for the business or the legal entities in the group. Senior management generally then translate these hurdles for each of the business lines, who benefit indirectly from the existence of the capital base. This hurdle rate can be a minimum for all the businesses (which is very unlikely as the returns per line of business vary greatly, for example, between asset and liability lines), or it can be modified to suit the differing requirements of each business. It is imperative to note how important it is for the bank's return on capital (RoC) target to be set at a Board level, reflecting the needs of the shareholder and thereby the “cost” of that equity.

The example below describes the treatment of share capital further.

The treatment and allocation of capital described here represents what is considered business best practice at the one bank observed. However, it is not universal. In some cases, a deviation from the above is justified where a portion of the capital base is allocated for use as “working capital”, for example, in a start‐up situation to cover cash requirements such as rental and salary expenses. In this case, the amount to be allocated should be identified in advance and once the business has declared a profit, then the same amount should be restored to the capital base or the bank needs to adjust its reported capital base. So there could well be other treatments of the capital base that are justified, hence some banks may still deviate from the above.

Expected and unexpected losses

Banks' normal course of business involves exposing themselves to risk of loss due to customer loan default. Losses will vary from one year to the next, unsurprisingly closely correlated to the economic cycle. The extent of exposure also varies, from “AAA”‐rated exposure to lower‐rated exposure, by type of customer, and product. The extent of collateral provided by a loan customer also dictates the level of loss.

Obviously, it is not possible to know in advance what the extent of loss in the next 12 months (or any time period) will be. Banks estimate the average level of losses they expect to incur over the next budgeting period based on their historical experience. This is the bank's expected losses. The level of expected loss dictates the nature of future business. For example, since it can be seen as part of the cost of doing business, expected loss levels will influence:

- The level of future balance sheet expansion and lending levels;

- The rate of interest charged to customers.

Banks must also, however, account for unexpected losses. This should be self‐evident: it would not be possible to estimate accurately what future losses will be. It is common for actual loss rates to far exceed expected loss rates, especially if historical rates were used to estimate expected losses and the last 5 years had seen the economy booming with the central bank raising interest rates. It is these unexpected losses that banks require a buffer of capital to absorb, and as was said earlier, if the bank is to manage itself on a going concern basis, this buffer must be sufficient to absorb losses and still remain above the regulatory minimum. Otherwise of course it would no longer be a going concern. This is because a bank that falls even 1 basis point below the regulator's minimum will suffer a loss of confidence and a run on the bank (as well as the inevitable credit rating downgrade to junk status).

Unexpected losses are harder to estimate than expected losses. The way it is approximated is the basis of the orthodox credit risk management methodology process in banks. Figure 15.2 provides a stylised illustration of the distribution of credit losses.

Figure 15.2 Expected and unexpected losses

Area B is the extent of unexpected losses, and the bank will calculate the probability of such losses and the amount.

Understanding the difference between capital and liquidity

It is evident then that a bank's capital base and its holding of genuinely liquid assets are of equal importance in helping to mitigate against its main bank balance sheet risks. Arguably, liquidity risk is of greater importance because a failure of liquidity sourcing can kill a bank in an instant, compared with a shortage of capital that may take longer to force the bank into failure. But this aside, it should be noted that in the same way as banks operating models differ, so does the type of risk exposure that capital and liquidity are used to manage against differ. We reiterate that capital is a liability, on the same side of the balance sheet as all other liabilities, and is a source of funding. The balance sheet has to balance of course, and liquid assets are on the other side of the balance sheet as a use of funding. (The most liquid asset is a deposit at the central bank, or failing that the domestic sovereign Treasury bill.) The requirement to have both sufficient capital and sufficient liquid assets requires balance sheet managers to be aware of the details surrounding the source of funds and the use of funds. In other words, how much capital is available capital that is perpetual (it has no repayment date), has no obligation to pay dividends, and can absorb losses on a going concern basis? And how truly liquid are the liquid assets?

Capital regulation

As will be seen later in this chapter, how much minimum capital a bank needs is determined by legislation – so the answer to this question is straightforward. Indeed, Basel III enshrines in law a limit on how much balance sheet leverage a bank can employ. But it is a useful exercise to determine what the capital requirement would look like if there was no regulator.

Certain key ratios (including the leverage ratio) help to provide an estimate answer to this question. This is because not all assets on a bank's balance sheet are the same – some assets are (credit) riskier than others, so each asset type is assigned a risk weight to reflect how risky it is deemed to be. These weights are then applied to the bank's assets to give a risk‐weighted asset (RWA) value. This is then used to calculate the capital ratio, the bank's capital amount as a percentage of the RWA amount. It is seen that it is easy enough to alter the capital ratio value by adjusting either the numerator or the denominator – or both.

In such an instance the capital requirement would be based on the internal view of risk and the level of financial resources required to ensure the bank remains a going concern within the tolerances set by its risk appetite. This is the economic capital requirement of the bank.

KEY CAPITAL CONSIDERATIONS

For a bank to ensure that it has adequate capital to support its business, it must consider the following:

- Regulatory requirements;

- Risk appetite and risk profile;

- Rating agency (for example, S&P) considerations;

- Equity investor expectations.

Regulatory requirements will be the primary driver of the bank's capital structure, involving consideration for a number of metrics across the regulatory spectrum. The Board sets the risk appetite of the firm. One of the risk appetite metrics will consider the level of friction the bank wishes to endure before breaching regulatory requirements. Capital will be held as a buffer on the regulatory buffer to minimise regulatory friction. Also, from an S&P perspective, risk‐adjusted capital (RAC) is an important ratings score determinant and is key in influencing the achievable optimum capital mix. Equity investor considerations around dividend capacity and RoC expectations would influence the capital mix. The importance of each factor will vary according to the risk appetite of each firm.

Regulatory requirements are those of the national regulator and international regulatory considerations as set by the Basel capital rules. In the UK, for example, the requirements would include the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRDIV) (the European Union's legislative implementation of Basel III), the buffer requirements of the UK Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA), the leverage ratio, and also any relevant ring‐fencing rules. For a bank in South Africa, the considerations are similar as the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) is a member of the Basel Committee. The SARB compares the capital strategies of banks by type of bank with smaller banks having considerably higher capital requirements than their larger counterparts, given the lack of diversification in the portfolio.

A rating agency will consider issues including: access to bank financing, issuance capability in the capital markets, implicit support for government or a foreign parent, and the price the bank has to pay to raise long‐term funding.

Equity investors will be concerned with the “value vs growth” equity outlook, the formal dividend policy, and their expectations for RoC. These are considered in further detail below.

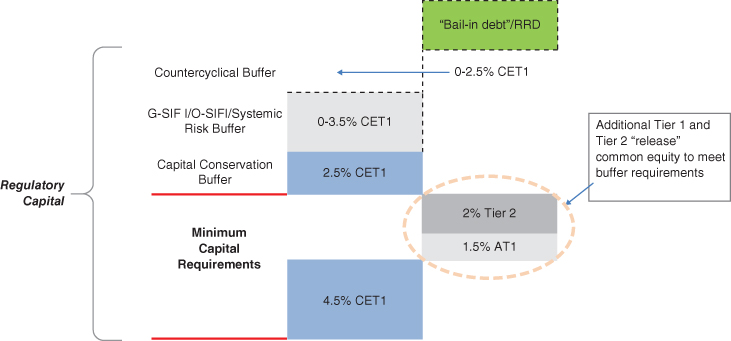

Regulatory capital requirements

In the first instance, capital structure considerations are essentially given by the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR)/CRDIV (in the EU) and in other jurisdictions by the local interpretation of Basel III. Figure 15.3 is a summary of this requirement.

Figure 15.3 Capital structure considerations under CRR/CRDIV

For Basel III, paper BCBS 189 (June 2011) footnote 47 states:

Common Equity Tier 1 must first be used to meet the minimum capital requirements (including the 6 per cent Tier 1 and 8 per cent Total capital requirements if necessary) before the remainder can contribute to the capital conservation buffer.

For banks in the EU, the requirement of CRDIV as stated in Article 124 (July 2011) is that:

Institutions shall meet the requirement imposed by the Countercyclical Capital Buffer with Common Equity Tier 1 capital, which shall be additional to any Common Equity Tier 1 capital maintained to meet the own finds requirement imposed by Article 87 of Regulation [total capital ratio of 8 per cent], the requirement to maintain a Capital Conservation Buffer…

The buffers set in the capital requirements can be utilised during times of stress. However, in such circumstances distributions to shareholders and staff will be restricted.

Sources of capital

Core equity Tier 1 capital consists in principle of share capital, share premium, and retained earnings attributed as regulatory capital. Certain deductions apply.

The features that make a long‐dated liability eligible as Additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier 2 (T2) are as follows:

AT1:

- Perpetual; not callable prior to year 5;

- Non‐cumulative, discretionary distributions;

- Deeply subordinated;

- Conversion to equity or principal write‐down at a trigger of CET1 < 5.875% (or higher);

- Conversion or write‐down at the point of non‐viability, where the point of non‐viability is determined at the discretion of the SARB prior to the failure of the bank.

T2:

- Minimum maturity of 5 years (with capital credit amortising 20% per year 5 years prior to maturity);

- Subordinated;

- Conversion or write‐down at the point of non‐viability.

Given the requirements of Basel III, at a strategic level the main ingredients of capital planning are essentially given: that is, the attachment points for maximum distributable amounts can be set quite easily. The most transparent way to illustrate this is to assume that one is setting up a bank from scratch, as shown in Table 15.1, with the theoretical illustration at Figure 15.4 and 15.6.

Table 15.1 Capital framework based on the Basel III framework: hypothetical bank start‐up

Figure 15.4 Combined buffer requirement for a bank under Basel III

Figure 15.5 RWA breakdown

The Pillar 2A add‐on is stipulated by the national regulator.

In other jurisdictions, as in the UK, the PRA has stated that the Pillar IIA add‐on of up to 2% must comprise at least 56% CET1 and the remainder of a combination of AT1 and T2. For a new bank, the minimum capital requirement would allow the requirements under Basel III to be met, as well as to allow for sufficient capital should a countercyclical buffer requirement be implemented by the regulator SARB.

Hypothetical example: vanilla commercial bank

To illustrate the considerations involved from a first‐principles basis, an assumed example of a UK commercial bank that is being set up from scratch, with an inherited portfolio, is considered. What would be the primary factors driving the capital planning process? The balance sheet RWA breakdown is shown in Figure 15.5.

The main factors that (say) a ratings agency review would consider include: asset mix (for example, whether there is a concentration in assets such as commercial real estate (CRE)); advanced – vs foundation – IRB being applied; Pillar II impacts; stress buffers required; and any capital release opportunities. With a total balance sheet RWA of just over GBP 13 billion, the bank is below 1% of UK GDP in size, so the countercyclical, globally systemically important institutions (G‐SIFIs), and ring‐fence buffers do not apply. Hence, the capital considerations that must be accounted for are shown below.

Figure 15.6 Capital considerations

This argues for an indicative capital structure of 15%. However, as this is a fairly small portfolio, the individual capital guidance received from the regulator will more likely impose a higher requirement. This would be a working assumption taking into account:

- Regulator feedback (for example, the requirement for the amount of total loss‐absorbing capacity);

- Potential impact of stress tests on the capital plan. Such stresses are then accounted for to a certain level of confidence using economic capital principles;

- Peer‐group analysis;

- Market expectations;

- Rating agency feedback.

Assuming the 15% capital base is accepted as a minimum requirement, there are two main scenarios that present themselves. The first is Scenario 1, the all‐equity scenario, while Scenario 2 describes an equity plus other capital structure. The latter is shown in Figure 15.7.

Figure 15.7 Hypothetical new bank capital structure minimum compliance with Basel III

A capital base as shown in Figure 15.7 would enable the bank to meet both the standing buffer requirements and the macro‐prudential one. Note that the PRA has stipulated that CET1 must be used to fill Pillar IIA requirements prior to the combined capital buffer. The residual 3.0% of CET1 would be available to meet any remaining capital or buffer requirements, including the Pillar IIA requirements.

What factors should guide the capital planning process with respect to the structure of the capital base? The all‐equity scenario presents the following features:

- The most robust form from a regulatory perspective;

- It may result in an incremental (one‐notch) rating benefit;

- As the most expensive structure, it is least efficient from a shareholder return perspective;

- Compared to the equity plus other capital format, there is a substantial decrease in RoC.

The equity plus other capital liability structure has the following features:

- It is a more efficient capital structure;

- Ultimately, it remains subject to national regulatory approval;

- The rating agency position towards this structure is neutral to negative;

- The T2 issuance would of course be subject to investor demand for this paper;

- The structure allows for further gearing/leverage of the capital base. The level of leverage is restricted under Basel III and in particular in South Africa as discussed below.

Table 15.2 is a summary of the requirements for capital instruments to be AT1 and T2 eligible. In its capital planning, a bank may consider the following rationale for issuance of one or both of these instruments:

Table 15.2 AT1 and T2 instrument requirements

| Additional Tier 1 | Tier 2 | |

| Tenor | Perpetual | May be dated. Must have minimum 5 years maturity |

| Subordination | Subordinated to depositors, general creditors, and subordinated debt of the bank | Subordinated to depositors and general creditors of the bank |

| Distribution | Bank must have full discretion to cancel payments (non‐cumulative) | No requirement for deferral/ cancellation of coupon |

| Call features | May be callable by the issuer after a minimum of 5 years (subject to regulatory approval) | May be callable by the issuer after a minimum of 5 years (subject to regulatory approval) |

| Going concern loss absorption | Must have principal loss absorption through either conversion to shares or a write‐down mechanism | N/a |

| Gone concern loss absorption | Write‐off or conversion if required by the regulator | Write‐off or conversion if required by the regulator |

- Free up common equity to count towards buffer requirements (capital buffers are additive to minimum total capital requirements);

- Pillar II or bail‐in capital requirements;

- Non‐dilutive (absent conversion);

- Tax deductible;

- Able to be sold to a fixed income investor base;

- Acts as a cushion for senior debt investors;

- Supports credit rating requirements (S&P RAC eligible).

In undertaking its capital planning, a bank must consider the Pillar II requirements. When conducting its Pillar II review (that is the review of the bank's Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process or ICAAP), the local regulator will consider both those risks to banks that are not fully captured under Pillar IIA and those risks a firm may be exposed to in future, for example, regulatory changes (Pillar IIB). The key considerations are:

- Pillar IIA: in addition to the Pillar I requirements of Basel III (in the EU, CRR/CRDIV), certain regulators including the PRA regard Pillar IIA capital as the minimum level of regulatory capital a bank should maintain at all times to cover against risks, with the implication being that CET1 must be used to fill the Pillar IIA requirement prior to being used for the capital conservation buffer (CCB);

- Pillar IIB: Pillar IIB buffers will be required for firms where the regulator (PRA included) deems that the Basel III or CRDIV buffers may not be sufficient to enable a firm to meet its capital requirements under stress. The Pillar IIB buffer will replace the existing (in the UK jurisdiction) capital planning buffer (CPB), and will be set based upon a range of factors, including firm‐specific stress test results.

Leverage ratio

The leverage ratio limit is a Basel III requirement. It will initially be implemented as a Pillar II measure, although from January 2016 it will be a binding measure. However, prior to harmonisation, at this point national regulators are free to apply the leverage ratio requirements as they see fit. The Bank of England has already applied the 3.33% ratio limit, and the numerator is given by Tier 1 capital.

In CRDIV the leverage ratio is defined as T1 capital divided by a total exposure measure; the simplest form is given by:

Credit rating considerations

In proceeding with issuance of an AT1 or T2 hybrid capital instrument, the capital planning process will also consider the treatment of the instrument by the international credit rating agencies (S&P, Moody's, Fitch). Ideally, the instrument will be eligible as capital, therefore strengthening the capital base to the benefit of the bank's final rating. S&P, for instance, issue guidelines for eligibility as RAC capital.

CAPITAL MANAGEMENT POLICY

Bank capital management should be articulated formally in a policy standard in the same way that liquidity management is (described in Chapters 8, 9 and 10). The objective of the policy is to describe how the bank will:

- Meet its regulatory and other legal obligations;

- Maintain its capital resources and buffer as required and in line with the stated risk profile of the business;

- Manage its capital planning in an efficient and cost‐effective manner;

- Recover from stress events.

A benchmark standard template for a bank's capital management policy is given here.

Capital management

The starting point for the capital management policy is the regulatory capital ratios. The requirements of any overseas regulators, from jurisdictions that the bank also operates in, are also included. The next step is a consideration of internal capital requirements (economic capital) as the Board has a duty to meet regulatory requirements but where these requirements are inadequate, as indicated by the internal risk assessment, to demand higher capital ratios. The buffers on regulatory ratios are required to reduce the likelihood of a limit breach and form the basis of the capital risk appetite of the bank. This is followed by a description of the monitoring process and escalation process for limit breaches.

The policy template would cover:

Capital targets

The bank will monitor and report its forecast regulatory capital base and risk‐weighted assets (RWAs) per business line to Finance, Risk, and Treasury. The responsibility for regulatory reporting lies typically with the Regulatory Reporting department within Finance. The bank's current operational targets are:

| Core Tier 1: | [ ] % |

| Total Tier 1: | [ ] % |

| Total capital: | [ ] % |

The Finance department will maintain a 3‐year rolling forecast and report this to ALCO. Forecast or actual breaches of the internal capital ratios and ultimately the regulatory capital ratios will be reported to the Head of Treasury and to ALCO as well as the regulatory authority. A regulatory breach should be very rare and the bank's risk management processes will require escalation prior to such an event. Upon escalation, management actions will be considered to rectify the position.

The Treasury department will undertake capital stress testing to assess the potential capital impact of changes in firm‐specific and market‐wide business conditions. Where the test results indicate a potential breach of target ratios, this must be reported to ALCO. Mitigating action should then be undertaken after approval from ALCO.

The actions considered to rectify any capital adequacy positions will also be tested during the stress testing exercises. There, actions range from the improvement of business processes, the sell‐down of assets, and the change in balance sheet strategy, to a rights issue to obtain more capital. Each action will have wide ranging impact and therefore needs to be considered in detail.

Risk‐weighted assets and economic capital demand

RWA balances (i.e. the regulatory Pillar I view of risk) and economic capital demand (the internal view of risk) must be reported to Finance, Treasury, and the business lines. The frequency of reporting may vary from inter‐day to monthly depending on the type of risks. RWA forecasts are prepared at month‐end; any inconsistency with the Finance general forecast must be reported to ALCO. The RWA forecast should be in line with the bank's capital allocation process. The impact of any business line transaction, whether asset or liability, that is likely to result in a reduction in capital must be reported immediately to ALCO. The process applied is similar in nature to the actuarial control cycle.

Business line profit

The net profit after direct and indirect costs of each business line must be transferred to the central book at year‐end. This is a direct cash transfer.

Capital resource management

A subset of the capital management policy is the capital resource management policy. The object of this document is to articulate formally how each business line will meet its requirements with regard to adherence to the capital management policy standard, and to ensure that use of capital at the business level is at an optimum in terms of allocation, planning, and management. The efficient use of capital is also a metric in business performance evaluation. The capital resource management policy is part of the process to ensure that capital is allocated efficiently and as part of the bank's strategy.

Capital allocation

Each business line prepares a business case for capital demand, based on RWAs and economic capital. Each business case contains key metrics, including RoC, net generation of equity, and economic profit. The Balance Sheet Management department sets targets for RWAs and capital usage as part of the budget forecast and allocation process. Capital is allocated to produce optimum return, in line with the strategy and risk appetite of the bank. The strategy and risk appetite will drill down to each business line. Treasury Balance Sheet Management will present capital usage limits at month‐end, for approval by ALCO (see Chapter 10 for template Treasury organisation structure). Treasury Balance Sheet Management will report current and forecast capital usage to ALCO on a weekly basis.

If a forecast exceeds a limit, the business line will submit a request for mitigating action to be taken, or for an increase in limit.

Performance metrics

The Board, having delegated authority to the executive management committee (ExCo), will set performance metrics targets for each business line. This will include RoC and capital usage (RWA) metrics, against which performance of each business is evaluated. Some banks also consider economic profit or profit after regulatory capital cost, depending on which view of risk is more onerous.

Portfolio credit risk management

ALCO is responsible for reviewing and approving the asset pool for credit risk management purposes. This is to ensure that provisions are signed off in a consistent manner, that all transactions are in line with the business strategy and risk profile, and that they follow policy on capital usage and regulatory requirements.

Capital management strategy

We conclude that bank strategy should focus on serving customers and driving the business via this customer focus. This strategy will be articulated in terms of a financial plan containing all key metrics. It should include a return on equity target set in advance, which is aligned to the bank's risk–reward preference. The capital strategy follows on from the overall strategy, and describes how and what capital is allocated to each business line. The plans are then stress tested. The outcomes indicate the potential frictions that may be experienced by each business area. At that point, the bank sets its core Tier 1 capital target level to achieve in line with the risk appetite set by the Board. The point being made here is that capital strategy is a coherent, articulated, and formal plan of action that builds on a regular review of the business, allocation of capital to those businesses, and desired return on capital. This should all be documented as part of the bank's capital strategy, which feeds into the overall strategy. This may sound obvious, but the layperson would be surprised by how few banks actually do this.

A bank's management may think that the core Tier 1 ratio to have in place is the starting point of the strategy. In fact, almost the contrary could be true: the desired core equity Tier 1 ratio should be arrived at after consideration of the business lines, the results of stress testing, and the share of capital allocated to each to support the revenue and return on equity target that is desired. The bank should compile an annual, 3‐year, and 5‐year capital ratio target, aligned to a strategic funding plan, and then target the optimum Tier 1 ratio through setting optimal capital structures. This will be achieved through management of dividends (regular or special), rights issues for significant opportunities, AT1 and T2 issuances, or repurchases and liability management exercises.

Figure 15.8 Formulating capital management strategy

Source: Choudhry 2012.

As a key part of strategy, the capital management framework at a bank should address the requirements of all the various stakeholders. It should be communicated in a transparent fashion to all internal and external stakeholders, articulating:

- How the risk appetite is aligned to their needs and expectations;

- How and why capital allocation and capital constraints are integrated with funding capabilities and assigned to each business line;

- The extent of tolerance for earnings volatility;

- The framework in which each of the business lines operates, with respect to risk exposure and the type of business undertaken.

Figure 15.8 is a reprise of the capital management strategy process. Bank's capital management is part of the overall strategy and is encompassed in a “capital management framework”.

Stress testing, as part of the regulatory capital adequacy process, is considered in a later section.

CAPITAL ADEQUACY AND STRESS TESTING

To recap, Pillar I of the Basel regulatory capital framework describes the capital requirements for credit, market, and operational risk, while Pillar II focuses on the economic and internal perspective of banks' capital adequacy. Banks are required to employ satisfactory procedures and systems in order to ensure their capital adequacy is sufficient over the long term, with due attention to all material risks. These procedures are referred to collectively as the internal capital adequacy assessment process or ICAAP. The standard process by which the regulator determines whether a bank is managing capital on a satisfactory basis is also referred to, almost universally, as the ICAAP, which sometimes is taken to refer to the individual capital adequacy assessment process. It is known by other terms in certain jurisdictions, but irrespective of the name, we refer here to the process by which a bank stress tests its capital level for sufficiency through a range of scenarios and presents its results to the regulator. The regulatory authority will determine if it agrees with the results and thereby determine the level of capital required.

The ICAAP enables them to identify, measure, and aggregate all material risk types and calculate the economic, or internal, capital necessary to cover these risks. As such, the ICAAP process is key to the preservation of financial stability and is subject to a high degree of supervisory scrutiny, which does on the other hand make the process very bureaucratic and administrative. That said, because banks come in many different shapes and sizes, and a variety of balance sheet risk exposures, a number of different approaches may be observed when it comes to the ICAAP process. Business best practice for a vanilla commercial banking institution is described here.

ICAAP primer

In essence, the Basel Accord and its amendments form the basis for the ICAAP. In the EU, the legislative framework was described in CRD2. Further guidance was provided by CEBS (2006), which published 10 principles for the implementation of a consistent and comprehensive ICAAP. In short, all banks are required to document and specify fully the ICAAP, integrate it into the regular risk management process, and review it continuously to ensure it remains fit for purpose.

The ICAAP needs to be a risk‐based document, comprehensive and detailed, as well as forward looking. Of course, the results of the ICAAP process need to be consistent with the bank remaining a going concern – if they are not, the bank's Board must implement management actions to redress the matter before presenting results to the regulator. While there is considerable commonality, each ICAAP is ultimately unique to the bank in question, reflecting its specific balance sheet structure and exposure.

Risk taxonomy and quantification

Before quantifying balance sheet risk exposure, it is important to categorise it, or as some banks term it, compile a taxonomy of risk. Not all banks exhibit all identified risk type exposures. Under Pillar II, all material risk types need to be quantified, and thereby covered with adequate capital provision. Certain types of risk (conduct risk, reputation, etc.) are not straightforward to quantify, so banks will apply a qualitative assessment. Typically, banks and, crucially, certain regulators employ the Value‐at‐Risk (VaR) technique to estimate risk exposure on the balance sheet. For those familiar with VaR, the logic of its methodology is consistent with a trading book, or a pool of assets that are repriced on a regular basis. However, this logic is less consistent in a banking book. Nevertheless, the VaR approach remains the one that is most in use and often demanded by the regulator to assess the VaR to the firm. The actual methods vary from simple risk weights to detailed economic risk assessments. In addition, regulators use peer group comparisons as well and any outliers per business area are interrogated further.

Table 15.3 summarises the Level 1 risks within the risk taxonomy for a vanilla UK commercial bank, with 1st and 2nd line‐of‐defence (LoD) responsibilities indicated.

Table 15.3 Level 1 risk taxonomy

| Level 1 Risk Taxonomy | |||

| The table below summarises the Level 1 risks within the risk taxonomy for Rainbow | |||

| Level 1 Risk | 1st LoD Risk Owners | 2nd LoD Risk Owner | Definition |

| CREDIT | MDs of each business area/MD Sales and Marketing | CRO | Risk of loss from the failure of a customer to meet their obligation to settle outstanding amounts, including concentration risk. |

| OPERATIONAL | COO, Head of HR, Legal and CFO | The risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, or from external events, including legal risk and supplier risk. | |

| IT | Head of IT | Loss of technology services due to loss of data, system, or data centre including, where applicable, failure of back‐up processes and/or a third party to restore services. | |

| COMPLIANCE | ExCo members | The risk of material financial costs (including rectification and remediation costs), legal and regulatory sanctions, or reputational damage the bank may suffer as a result of its failure to comply with relevant laws, regulations, principles, rules, standards, and codes of conduct applicable to its activities, in letter and spirit. Within compliance:

|

|

| NON‐TRADED MARKET RISK | Head of Treasury | The market risk arising in non‐trading assets and liabilities. | |

| CAPITAL AND STRESS TESTING | CFO | The risk of not being able to conduct business in base or stress conditions due to insufficient qualifying capital as well as the failure to assess, monitor, plan, and manage capital adequacy requirements. | |

| FUNDING AND LIQUIDITY | Head of Treasury | The risk that the company is not able to meet its liabilities as they fall due, or has insufficient resources to repay withdrawals. | |

| REPUTATIONAL | ExCo members | The risk of brand damage and/or financial cost due to the failure to meet stakeholder expectations of the company's conduct and/or performance. | |

| BUSINESS | CFO/(+MDs of business areas) | The risk that the company suffers losses as a result of adverse variance in its revenues and/or costs relative to its business plan and strategy. | |

| STRATEGIC | CEO (Board) | The risk that the company will make inappropriate strategic choices, is unable to successfully implement selected strategies, or changes arise that invalidate strategies. This includes all divestment programme‐related risks. | |

| GROUP | CEO | The dependency of the company on the group for key support areas, e.g. funding, liquidity, capital, and other back office functions, etc. | |

It is common to see the variance‐covariance (“parametric”), historical simulation, and Monte Carlo simulation approaches used in equal measure among banks. Typically, banks apply a 1‐year holding period and one‐sided confidence levels of 95% or 99%. For market risk, banks often apply a 1‐day and 10‐day holding period. Note that most banks classify interest‐rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB) as a market risk, albeit a non‐traded market risk. Again, it is common to observe VaR as the preferred measurement technique for IRRBB as well; however, the author's recommended approach is to supplement this with traditional modified duration analysis (“gap” analysis) as well.

Stress tests

In the post‐2008 era, all banks, except perhaps the very smallest, specify a large number and variety of stress tests. That said, there is considerable commonality in approach. Generally, the primary focus is on scenario analyses, often based on 5‐year historical worst‐case values or hypothetical scenarios. The latter are sometimes also required to include a “reverse stress test”, which is a hypothetical scenario that would break the bank. In theory, as stress tests allow for the identification of sensitivities to specific risk factors, they should be a worthwhile exercise as they provide value‐added input to the bank's risk management process and subsequent management actions. The danger, as with all exercises subject to considerable regulatory supervision, is that the stress testing process becomes an excessively bureaucratic one and more of a “box‐ticking” exercise. This must be avoided and ALCO is the appropriate forum to review the process and ensure this does not happen.

ICAAP process guidelines

To recap, Basel II introduced the three‐pillar architecture for capital and risk management (see Figure 15.9, as reproduced from the BCBS document).

Figure 15.9 The three pillars of capital and risk management

On the one hand, Pillar II (Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process) requires banks to implement a process for assessing their capital adequacy in relation to their risk profiles as well as a strategy for maintaining their capital levels. This is the ICAAP. On the other hand, Pillar II also requires the regulatory authority to review all banks for their capital adequacy and to impose any necessary supervisory measures following such review. So there are two parts to this process:

- The ICAAP, which comprises all of a bank's procedures and measures designed to ensure that there exists:

- The appropriate identification and measurement of all balance sheet risks;

- An appropriate level of internal capital in relation to the bank's risk profile;

- The application and further development of suitable risk management systems.

- The supervisory review process or SRP (sometimes SREP), which covers the processes and measures defined in the principles listed above, including the review and evaluation of the ICAAP process, an independent assessment of the bank's risk profile, and where necessary instructing the bank to undertake further prudential measures.

ICAAP implementation

Before a bank can begin designing its ICAAP, it should first define its relevant target state. The steps involved are those illustrated in Figure 15.10.

Figure 15.10 Steps involved in the ICAAP production and approval process

© Chris Westcott 2017. Used with permission.

What does Figure 15.10 mean in practice? Each step is considered in turn below.

Definition of bank‐specific requirements (target state): In the first step, the bank compiles its strategy based on its goal or vision. It will test this strategy against a list of requirements based on national regulator statements, for example, the EU CRDIV. Next, these requirements have to be specified for the individual bank, thus in the course of a self‐assessment the bank should identify its material risks, which arise from the implementation of its strategy. The ICAAP therefore facilitates assessing the sensitivity and risks in a firm's strategy. The requirements with regard to ICAAP methods should be defined in light of the bank's risk profile, as they need to be fit for purpose but also meet regulatory rigour. Typically, the introduction of new methods begins with relatively simple, robust solutions which are then developed and refined on an ongoing basis. The full list of requirements then represents the target state for ICAAP purposes and defines requirements with regard to methods, procedures, processes, and organisation.

Gap analysis: Once the target state has been defined, the bank should analyse those requirements that are currently not (or not completely) fulfilled. These gaps pertain both to the execution of strategy as well as the capital assessment process. It is the business team's responsibility to address the former and its risk management teams would survey the current state of methods, processes, and organisation in place in the internal risk management system. This might include the regulator's requirements for calculating capital amounts, or activities aimed at fulfilling the minimum standards for the credit origination business. The process is not restricted to risk managers. In terms of the three lines of defence model, the process starts with all business lines, which should analyse their current state and report it centrally to Risk (and ALCO). Gaps in implementation can then be identified by comparing the requirements with the current state. This comparison of target and actual states could be carried out in the course of a workshop attended by representatives from the business lines, with the results documented and reported to all relevant stakeholders. The bank can then assess the significance and consequences of the gaps identified as well as identify the necessary management actions as a result.

Implementation planning: In implementation planning, the first step is to prioritise the required measures identified in the previous process. This way a clear ranking can be defined in order to deploy implementation resources effectively. Measures identified should be combined in individual work packages and coordinated with business lines; this process requires that specific roles and responsibilities be identified and assigned. As part of the process, the bank should set binding deadlines, which reflect resource and capacity available within the firm.

Implementation: Put simply, this stage involves undertaking and delivering on the process measures identified in the previous stage. This includes employing human resources as well as IT capacity as required by the ICAAP. The process‐related aspects and responsibilities within the ICAAP can then be defined and documented. This may involve quantifying and aggregating risks and coverage capital, monitoring limits, or taking measures in the ex‐post control process. The ICAAP is integrated into the bank's strategic and operational control mechanisms (for example, annual budgeting and planning on the basis of risk indicators and coverage capital). Once implementation is completed, the bank should have in place adequate methods, processes, and systems to ensure its risk‐bearing capacity over the long term.

What makes a good ICAAP?

In essence, the ICAAP process and its published output as presented to the national regulator should be a value‐added exercise that reflects the interests of all stakeholders in the long‐term viability of the bank as a going concern. This is not a platitude. However, because of the onerous regulation and reporting process in place in most jurisdictions, the process often boils down to producing something that the regulator signs off on. This is not the best approach to ICAAP production. To the question “What makes a good ICAAP?” the obvious answer is a document that presents the firm's strategy with all material risk exposures, on a forward‐looking basis, and demonstrates that these exposures are covered by adequate capital levels, risk management systems, and management actions to rectify stresses in order to ensure the successful implementation of the strategy.

As a checklist, we should note that the following factors are crucial in the actual implementation and successful presentation of an ICAAP:

- Early detection of gaps in fulfilment:

A bank should make efforts to detect gaps in the fulfilment of requirements as early as possible so that it can take the appropriate measures in a timely and economical manner. Closing these gaps quickly will improve the bank's internal risk management and thus enhances its ability to ensure its risk‐bearing capacity.

- Selection of methods:

The bank should determine the methods and procedures that best suit its needs, as these determine the validity of the ICAAP as well as the required implementation resources. In the course of selecting methods, the bank should not only consider its current risk profile but also anticipate planned developments in individual risk types. If, for example, a decision has already been made that trading will be expanded in the medium term, then it makes sense to introduce more advanced procedures from the outset when designing the ICAAP.

- Master plan and project management:

The bank should develop a master implementation plan that covers planning, budgeting, and a prioritisation of all ICAAP implementation tasks. There should be one overall, dedicated project manager (most probably someone within Risk or Treasury). This master plan forms the basis for requesting internal and external capacities and may well involve planning resources over a period of several years. For example, implementation might already be well under way for the most important risk types, while measures for other risk types are still being planned. Once it reaches a certain scale, the master plan should be transformed into a detailed project plan, which serves to reduce complexity and create transparency with regard to the current implementation status. It is also important to set binding deadlines and responsibilities on the basis of this plan. A project manager should then monitor and control the performance of individual tasks. Project management should seek to prevent any conflicts of interest between the business lines involved in implementation and to maintain an aggregate and holistic view of the project.

- Communication:

The need for, and benefits of, the ICAAP have to be clearly communicated to all staff. The fundamental concept of the ICAAP is not something for senior executives only to appreciate, but for all business lines. An example is a newly designed limit allocation system or a change to the organisation chart, more likely to be supported by staff if they are informed about the need for these measures in a transparent and understandable manner. Insufficient communication in implementation projects often results in low levels of identification or even rejection and demotivation. By applying an appropriate communication policy and setting a good example, senior executives should generate the employee acceptance necessary for successful implementation of the ICAAP.

- Know‐how and resources:

One major objective of the ICAAP is to foster the development of an appropriate internal risk management culture. For this reason, expertise in this area is a key success factor in the implementation of the ICAAP. It is important for the bank to have the necessary resources (employees, systems) at its disposal in the ICAAP implementation process. Resource requirements will depend on the bank's size and risk profile as well as the difference between the current status and the defined requirements.

- Data quality and IT systems:

Data quality (completeness, availability) is especially important because it determines the reliability and accuracy of calculated results (for example, risk indicators and coverage capital). The process of data quality assurance begins with accurate data capture and goes as far as ensuring data availability in the ICAAP. Especially for risk management, it is necessary and worthwhile to ensure timely automated evaluations due to the large data quantities involved and the sometimes complex calculation algorithms used. In its ICAAP, the bank can rely on existing risk management systems (risk measurement, limit monitoring) if they meet the defined requirements. Historically, maintaining and updating the IT structures of many banks requires copious resources. It is a required investment, however, because the lack of uniform data pools can create considerable difficulties in assessing the true extent of balance sheet risk.

Principal ICAAP requirements

Based on supervisory requirements and the benefits from a business perspective, the basic requirements to be taken into account in the production of an ICAAP are:

- Securing capital adequacy: Banks should define a risk strategy that contains descriptions of its risk policy instruments and objectives. This is a Board‐level statement. The explicit formulation of such a risk strategy aids in the early detection of deviations from appetite and tolerance;

- ICAAP as an internal management tool: The ICAAP should form an integral part of the management and decision‐making process;

- Responsibility of the management: The overall responsibility for the ICAAP is assigned to the Board and senior executive, which must ensure that the bank's risk‐bearing capacity is secured and that all material risks are identified, measured, and limited;

- Assessment of all material risks: The ICAAP focuses on ensuring bank‐specific internal capital adequacy from a business perspective. For this purpose, all material risks must be assessed. Therefore, the focus is laid on those risks that are (or could be) significant for the individual bank;

- Processes and internal review procedures: Merely designing risk assessment and control methods is not sufficient to secure a bank's risk‐bearing capacity. It is only in the implementation of appropriate processes and reviews that the ICAAP is actually brought to bear. This ensures that every employee knows which steps to take in various situations. For the sake of improving risk management on an ongoing basis, the development of an ICAAP should be regarded not as a one‐time project but as a continuous development process. In this way, input from ongoing experience can be used to develop simpler methods into a more complex system with enhanced control functions.

Risk indicators

The ICAAP should present all relevant material balance sheet risk through a series of risk exposure indicators. These are specific to the risk types. Indicators presenting the aggregate view are also required, i.e. the firm's capital adequacy ratios as well as risk‐adjusted performance indicators.

Credit risk indicators

The structure of the credit portfolio provides initial indications of a bank's risk appetite. A large share of loans in a certain asset class (for example, CRE) may point to increased risk. In addition, the presence of complex financing transactions such as specialised lending (project finance, for instance) may also indicate a larger risk appetite. For an approximate initial assessment, in the EU a bank can use the asset classes defined in Directive 2000/12/EC, or the asset classes outlined in the BA200 submission to the SARB, to examine the distribution of its credit portfolio. A bank can use credit assessments (such as credit ratings) to measure the share of borrowers with poor creditworthiness in its portfolio; this provides an indication of default risk. The bank will also consider the portfolio in terms of delinquency and impairment. The amount of available collateral – and thus the unsecured volume – also plays a role in this context. The lower the unsecured volume is, the lower the risk generally is; this relationship is also reflected in future supervisory regulations for calculating capital requirements. In this context, however, the type and quality of collateral are decisive; this can be assessed by asking the following questions:

- To what extent is the retention or liquidation of the collateral legally enforceable?

- How will the value of the collateral develop?

- Is there any correlation between the value of the collateral and the creditworthiness of the debtor?

A close inspection of the credit portfolio will provide further insights with regard to any existing concentration risks. In order to assess the size structure or granularity of its portfolio, the bank can also assess the size and number of large exposures. The bank should also consider the distribution of exposures among industries (for example, construction business, transport, tourism, and so on) in assessing its concentration risk. If a bank conducts extensive operations overseas (share of foreign assets), it is appropriate to take a close look at the risks associated with those activities as well, such as country and transfer risks. The share of foreign currency loans in a bank's credit portfolio can also point to concentration risks. If the share of foreign currency loans is very high, exchange rate fluctuations can have adverse effects on the credit quality of the borrowers. If the foreign currency loans are serviced using a repayment vehicle that is heavily exposed to market risks, this indicates an additional source of risk that should be monitored accordingly and controlled as necessary.

Market risks in the trading book, foreign exchange risks at the overall bank level

This exposure is calculated using a VaR approach. A bank can determine its sensitivity to foreign exchange fluctuations on the basis of its open foreign exchange positions and (in the broadest sense) open term positions. The influence of foreign exchange fluctuations on the default probability of borrowers with foreign currency loans is also considered.

Interest‐rate risk in the banking book

The results reported in interest‐rate risk statistics (part of regulatory reporting requirements) constitute an essential indicator of the level of interest rate risk in the banking book. The traditional approach here is to apply modified duration analysis such as parallel yield curve shifts (for example, the effects of a 200 basis point interest‐rate shock on the present value of the balance sheet). Of course, if this method demonstrates that material interest‐rate risks exist in the banking book, regulators usually require more “sophisticated” risk measurement methods to be applied, with output including a precise quantification of risks in terms of their effects on the income statement. Another risk indicator should cover proprietary trading both on‐ and off‐balance‐sheet. In accordance with the proportionality principle in the ICAAP (larger, more sophisticated balance sheets require larger, more sophisticated ICAAPs), the corresponding requirements increase in line with the scale of derivatives trading activities. Even in cases where a bank primarily uses derivatives to hedge other transactions or portfolios, the effectiveness of hedging transactions (the hedge effectiveness) should be examined in order to avoid undesirable side effects. In the case of on‐balance‐sheet proprietary transactions, the need for more precise risk control grows along with the scale and complexity of the positions held, for example, “alternative investments” or structured bonds.

Operational risk indicators

Two important indicators of operational risk are the size and complexity of a bank. As the number of employees, business partners, customers, branches, systems, and processes at a bank increases, its risk potential also tends to rise. Another risk indicator in this category is process intensity, for example, the number of transactions and volumes handled in payments processing, loan processing, securities operations, and proprietary trading. Failures (for example, due to overloaded systems) can bring about severe economic losses in banks with high levels of process intensity.1 The number of lawsuits filed against a bank can also serve as an indicator of operational risks. A large number of lawsuits suggests that there are substantial sources of risk within the bank, such as inadequate system security or insufficient care in processes and control mechanisms. In cases where business operations (for example, the processing activities mentioned above) are outsourced, the bank cannot automatically assume that operational risks have been eliminated completely. This is because a bank's dependence on an outsourcing service provider means that risks incurred by the latter can have negative repercussions for the bank. Therefore, the content and quality of the service level agreement, as well as the quality and creditworthiness of the outsourcing service provider, can also serve as risk indicators in this context.

The risk indicators may be presented as per the following template (note that more than one bank has been amalgamated to reflect different approaches), as illustrated in Table 15.4.

Table 15.4 Example risk indicator levels

For Bank A, the risk types mentioned above would have little significance under the proportionality principle. The bank shows a low level of complexity and low risk levels. Besides, Bank A does not have any trading positions. For the purpose of measuring its risks and calculating its internal capital needs, Bank A could calculate its capital requirements using the Standardised Approach, or the Basic Indicator Approach in the case of operational risk.

In terms of its total assets and number of employees, Bank B is comparable to Bank A, but Bank B's transactions show a markedly higher risk level. In addition, concentration risks exist with regard to size classes (for example, several relatively large loans to medium‐sized businesses), borrowers in the same industry, and foreign currency loans. In this bank, methods that go beyond the Standardised Approach should be employed and/or adequate qualitative measures (monitoring/reporting) should be set. Furthermore, Bank B should pay attention to concentration risks, for example, by adhering to suitable individual borrower limits based on creditworthiness or by implementing minimum standards for foreign currency loans. In this example, using more advanced systems may be appropriate in other areas, such as interest rate risk in the banking book.

Bank C shows high credit exposures to SMEs and has also granted a number of relatively large loans. This results in a certain degree of concentration risk. In addition, the bank is exposed to relatively high interest‐rate risks. In fact, Bank D has large exposures to almost all risk types. The bank's size and structure can be described (such as a VaR model) for interest‐rate risk at Banks C and D; Bank D should also use a more sophisticated model for market risk. Due to the higher risk level and the existing complexity with regard to credit risk, the bank may use other risk‐sensitive techniques based on the internal ratings‐based (IRB) approach or a credit portfolio model.

The individual institutions in this example have to define the scale and type of risk management system that is appropriate to their activities, with due attention applicable to the regulator's requirements. The choice of suitable risk measurement procedures to determine risks and internal capital needs plays a key role in this context. Moreover, the proportionality concept also has effects on process and organisational design: banks that demonstrate a high level of complexity or a large risk appetite have to fulfil more comprehensive requirements.

An example of the presentation of the risk indicators is given in Table 15.5.

Table 15.5 Sample incorporation of an institution's relevant risk types in the ICAAP

| Risk type | Risk subtype | Risk level | Justification (if immaterial) | Risk assessment procedure used |

| Credit risk | Counterparty/default risk | Very high | Foundation IRB Approach | |

| Equity risk | Immaterial | Equity investments as share of total assets < 0.5% | Foundation IRB Approach | |

| Country/transfer risk | Medium | Strict limitation (structural limit) | ||

| Securitisation risk | Immaterial | No involvement in securitisation programmes (neither as originator nor as investor) | Not considered | |

| Credit risk concentration | High | Strict limitation (structural limit) and increased monitoring | ||

| Residual risk from credit risk mitigation techniques | Medium | Qualitative assessment, process‐based reduction of risk (use of standard contracts, “four eyes” principle, regular revaluation of collateral, etc.) | ||

| Market risk | Market risks in the trading book | Low | Standard supervisory methods | |

| Foreign exchange risks in the banking book | Medium | Standard supervisory methods | ||

| Interest‐rate risks in the banking book | High | Value‐at‐Risk model | ||

| Operational risk | Medium | Basic Indicator Approach | ||

| Liquidity risk | Low | Qualitative measures | ||

| Other risks | Strategic risk | Medium | Cushion | |

| Reputation risk | Low | Cushion | ||

| Capital risk | Medium | Cushion | ||

| Earnings risk | Medium | Cushion |

Documentation requirements

The ICAAP is a living document. That means the Board must use the ICAAP document to familiarise and challenge risk as well as capital management processes in the bank. The ICAAP has to be designed in a transparent and comprehensible manner. This will not only aid bank staff in understanding, accepting, and applying the defined procedures, it will also make it easier for the bank to review the adequacy of its methods and rules regularly and to enhance them on an ongoing basis. Critically, it makes the SRP (or SREP) process by the regulator a smoother one.

For this reason, it is necessary to compile formal written documentation on all essential elements of the ICAAP. In creating the required documentation, the bank should ensure that the depth and scope of its explanations are tailored to the relevant target group. It is sensible to use various levels of detail in the actual implementation of documentation requirements. For illustration purposes, a sample scenario with three levels is shown in Figure 15.11.

Figure 15.11 Three‐level scenario

At the top level, it is advisable to articulate the bank's fundamental strategic attitude toward risk management. This will reflect the institution's basic orientation and guide all ICAAP‐related decisions. The basic strategic attitude can be documented in the form of the firm's strategy – that is, the purpose and objectives of the bank and how it executes on this purpose. This will be executed via a business plan. The business plan will be delivered subject to a risk strategy. The essential components of such a strategy include:

- Risk policy principles;

- Statements as to the bank's appetite;

- A description of the bank's fundamental orientation with regard to individual risk types;

- Comments on the current business strategy and future development of the business;

- Areas of risk and uncertainty in the business strategy, and how these risks are managed in terms of the risk policy principles and the bank's risk appetite.

The risk strategy should be approved by the entire management Board of the bank and so it should be in summary form. At the next level down, the bank should provide a more detailed explanation of the methods and instruments employed for risk control and management. In practice, such a document is frequently referred to as the bank's risk management policy manual. Essentially, the risk manual contains a description of the risk management process, definitions of all relevant risk types, explanations of evaluation, control, and monitoring procedures for risk positions (separate for each risk type), and a discussion of the process of launching new products or entering new markets. In general, the depth of these explanations also implies that it will be necessary to revise at least certain parts of the document on a regular basis.

This level of detail will be contained in the executive summary of the report. Further outline will be provided in the body, while all technical detail required will be provided in appendices to the document.

ICAAP PROCESS – WORKED EXAMPLE OF PRESENTATION

In this section, a worked example of a typical ICAAP presentation to a regulator is presented. The bank in question is a vanilla UK commercial bank with retail and corporate business line exposure, and with a balance sheet of approximately £22 billion.

Table 15.6 is a summary of the key ICAAP processes undertaken in the bank. Figure 15.12 illustrates the governance structure of the ICAAP framework, mapping the components of the ICAAP to the internal processes, governance, and approvals, ultimately for the regulatory review known as the “SREP”.

Table 15.6 ICAAP process

| Process | Short description |

| Risk appetite | Risk appetite is an integral part of ABC's risk management framework, designed to deliver the strategic risk objectives of capital adequacy, market confidence, stable earnings growth and access to funding and liquidity. |

| Material integrated risk assessment | An exercise that identifies, evaluates, and assesses all material financial and non‐financial risks whether quantifiable or not. |

| Stress testing programme | A comprehensive programme of stress testing that is designed to ensure senior management involvement, is aligned to regulatory requirements, and is integrated into the budgeting and capital planning processes. |

| 9+3 capital planning and budgeting | An annual budgeting and capital planning process incorporating business and financial plans for the current year and project at least an additional 2 years under a base case (normal conditions) and 3 years under stressed conditions. |

Figure 15.12 ICAAP governance process: the commonly observed process

The framework described in the foregoing could be said not to meet the “use test”, which requires that the process and planning are to be derived from the business strategy, and that the business lines take an active part in the process. Figure 15.13 is an illustration of an all‐embracing process for ICAAP preparation and submission, in that it shows the incorporation of the business lines. Figure 15.14 is a qualitative description of the process.

Figure 15.13 All‐embracing ICAAP governance process

Figure 15.14 Summary of the ICAAP planning and implementation process, linking strategy and capital management

Components of the internal capital assessment

The Basel regulatory regime prescribes three “pillars” of risk exposure capital input (see Chapter 2). In the UK, generally the capital assessment process combines two views: a point‐in‐time (Pillar I and Pillar IIA) and a forward‐looking (Pillar IIB) view. These are described as follows:

- Point‐in‐time capital assessment (1‐year horizon) Pillar I and Pillar IIA: these form part of an Individual Capital Guidance (ICG), which is the minimum capital requirements the bank has to meet at all times. Pillar IIA assesses risks not in Pillar I or risks not adequately captured under the Pillar I framework. The process is illustrated in Figure 15.15.

Figure 15.15 Point‐in‐time capital assessment (1‐year horizon) Pillar I and Pillar IIA

In an emerging market economy such as South Africa, a similar approach is used. Pillar I is fundamentally the same but Pillar IIA refers to an emerging market minimum capital requirement deemed by the SARB to be appropriate for South African banks. Banks prepare their own internal view of risk towards capital for the Pillar I requirement. This is based on internal economic capital models evaluated in aggregate rather than per individual risk type. Pillar IIB refers to the individual capital guidance and is set for each bank, based on the output of the bilateral SREP process where the regulatory capital requirement is compared to the internal/economic capital requirement.

- The capital planning buffer (CPB): which is part of the internal capital target, is the amount of capital to be held in addition to the ICG such that it can be used in stress to absorb losses in order to prevent the bank from breaching its ICG. It reflects the change in the capital surplus/deficit and is illustrated in Figure 15.16.

Figure 15.16 Capital surplus/deficit

The governance of this process is not cast in stone: different banks will organise it in different ways. Certainly, there is no one single correct way to approach this, but the governance structure must be fit for purpose in a way that provides confidence to the regulator and clearly articulates the risk appetite to the Board. The author's recommendation is first to compile a “risk taxonomy” associated with the capital management and ICAAP process, and then allocate roles and responsibilities based on this taxonomy.

In order to ensure a consistent approach to risk identification and measurement, it is preferable to compile a “risk taxonomy” associated with the risk management framework of the bank and used in the capital management and ICAAP process.