Chapter 10

Seven Magic Keys to Motivational e-Learning

Yes, I actually do have seven “Magic Keys” to making e-learning experiences compelling and engaging. As described in the previous chapter, motivation is essential to learning and one of the most important success factors for us to consider in designing and delivering instructional events.

Creating great e-learning is never as easy as following a recipe. I can't emphasize enough that there is a lot to know about instructional design and that although good e-learning design may look simple, it isn't. A great idea will often look obvious after it's been implemented, but uncovering the simple, “obvious” ideas can be a very challenging task. The keys to enhancing learning motivation put forth in this chapter are magical because they are such reliable and widely applicable techniques. Their presence or absence correlates well with the likely effectiveness of an e-learning application—at least to the extent that it provides motivating and engaging experiences. Thankfully, these features are not often more difficult to implement than many less effective interactions. These are realistic, practical approaches to highly effective e-learning.

Let's begin with Table 10.1, which lists seven ways to enhance motivation—the Seven Magic Keys—and then discuss them in more detail with examples.

Table 10.1 Ways to Enhance Learning Motivation—the Seven Magic Keys

| Key | Comments | |

| 1. | Build on anticipated outcomes. | Help learners see how their involvement in the e-learning will produce outcomes they care about. |

| 2. | Put the learner at risk. | If learners have something to lose, they pay attention. |

| 3. | Select the right content for each learner. | If it's meaningless or learners already know it, it's not going to be an enjoyable learning experience. |

| 4. | Use an appealing context. | Novelty, suspense, fascinating graphics, humor, sound, music, animation—all draw learners in when done well. |

| 5. | Have the learner perform multistep tasks. | Having people attempt real (or “authentic”) tasks is much more engaging than having them repeat or mimic one step at a time. |

| 6. | Provide intrinsic feedback. | Seeing the positive consequences of good performance is better feedback than being told, “Yes, that was good.” |

| 7. | Delay judgment. | If learners have to wait for confirmation, they will typically reevaluate for themselves while the tension mounts—essentially reviewing and rehearsing! |

Using the Magic Keys

You don't have to use every Magic Key in every application to make them effective. You would be challenged to do it even if you were so inclined. However, the risk of failure rises dramatically if you employ none of them.

Although it's rather bold to say, I contend that if you fully employ just one of these motivation stimulants, your learning application is likely to be far more effective than the average e-learning application. Everything else you'd do would become more powerful because the learner would be a more active, interested participant.

Magic Key 1: Build on Anticipated Outcomes

Magic Key 1: Build on Anticipated Outcomes

We have motives from the time we are born. As we mature, learned motives build on and expand from our instinctive motives. All our learned motives can probably be traced to our instinctive motivations in some way, but the helpful observation here is that human beings have an array of motivations that can be employed to make e-learning successful.

A simple and effective technique to build interest in an e-learning application is to show how it will bring learners benefits like comfort, competence, influence, self-esteem, and other prime motivations. The question is how to communicate those benefits.

Instructional Objectives

Much has been made of targeted outcome statements, or instructional objectives, perhaps beginning with Robert Mager's insightful and pragmatic how-to books on instructional design, such as Preparing Instructional Objectives (Mager, 1997c), Measuring Instructional Results (Mager, 1997b), and Goal Analysis (Mager, 1997a). Instructional designers are taught to prepare objectives early in the design process and to list learning objectives for learners at the beginning of each module of instruction. Few classically educated instructional designers would consider omitting the opening list of objectives.

Mager provides three primary reasons why objectives are important:

- Objectives…are useful in providing a sound basis for

- Selecting or designing instructional content and procedures

- Evaluating or assessing the success of the instruction

- Organizing learners' own efforts and activities for the accomplishment of the important instructional intents. (Mager, 1997c, p. 6)

There's no doubt about the first two uses. If you don't know what abilities you are helping your learners build, how can you know if you're having them do the right things? As I've emphasized before, success depends on people doing the right thing at the right time. If no declaration of “the right thing” is established, you can neither develop effective training nor measure the effectiveness of it—except, perhaps, by sheer luck. Objectives are a studied and effective way of declaring what the “right thing” is. As Mager says, “if you know where you are going, you have a better chance of getting there” (Ibid).

It's the third point that's of interest here—using objectives to help learners organize their learning efforts. Certainly, objectives can help. When objectives are not present, learners must often guess what is important. In academic or certification contexts when objectives are not shared, learners must guess what will be included in the all-important final examination. After they have taken the final exam, learners know how they might have better organized their learning efforts. But, of course, it's too late by then.

There is a bit of gamesmanship here that some instructors use. They justify it by saying comprehensive tests would be too difficult to prepare, require too much time to take, and be too laborious to score. If students don't know what's going to be tested, they'll have to prepare themselves for testing on all topics, even if the test only covers a sampling.

There's logic to it, but definitely downsides as well. Are the topics which are not tested unimportant? If scores are to be reflective of performance mastery, what are we to assume about untested skills? Aren't some performance skills more important than others? And if so, shouldn't learners be aware of this so they can concentrate their study on the most important things? Aren't some objectives just enablers, the mastery of which has little value on its own? Do courses impart so many useful skills they can't all be tested?

For objectives to provide benefits to learners, learners have to read, understand, and think about them. Unfortunately, learners rarely spend the time to read objectives, much less use them as learning tools. Rather, they discover that the objectives screen is, happily, a screen that can be skipped over quickly. Learners think, “I'm supposed to do my best to learn whatever is here, so I might as well spend all my time learning it rather than reading about what I'll learn.” Next.

Lists of Objectives Are Not Motivating!

Let's just admit it: Listing objectives at the start of a courseware module looks professional and makes us feel we've done the right thing, but those lists probably aren't going to contribute much to the learning experience. Many designers hope objectives will not only help learners organize their study but also enhance their motivation to learn the included content. Will they? Obviously, objectives do nothing if learners don't read them as we've said. But just how readable are they? Following Mager, knowledgeable instructional writers know objectives should have three parts (see Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 Components of instructional objectives.

Instructional writers have learned the importance of writing behavior-based objectives that are observable and measurable. (See Table 10.2 to get the gist of it.)

Table 10.2 Behavioral Objectives—Acceptable Verbs

| Not Measurable | Measurable |

| To know | To recall |

| To understand | To apply |

| To appreciate | To choose |

| To think | To solve |

Measurable behavioral objectives are, indeed, critical components to guide the design of effective training applications. Designers need such objectives, and none of these components should be missing from their design plans. But the question here is about their use as learning motivators.

You can hardly yawn fast enough when you read a stack of statements containing “proper” objectives like:

Given a typical business letter, you will be able to identify at least 80 percent of the common errors by underlining inappropriate elements or placing an “X” where essential components are missing.

After reading a few of these objectives, will you be motivated? Sure. You'll be motivated to skip the rest and move on. Objectives are important for us as designers and attainable outcomes are valuable to learners, but listing such statements as these in bullet points at the start of a program is boring and ineffective. If there are better ways to motivate learners, what are they?

How about Better-Written Objectives?

We can and should write objectives in more interesting ways and make them more relevant to the learner. Indeed, when they're deciding just how much energy and involvement to commit, learners want to know in what way the material will be meaningful to them personally (i.e., how the instructional content relates to their personal network of motivations). Effective objectives answer the question and give motivation a little boost (see Table 10.3).

Table 10.3 More Motivating Objective Statement

| Instead of Saying… | You Could Say… |

| After you have completed this chapter, given a list of possible e-learning components, you will be able to select the essential components of high-impact e-learning. | In a very short time, say about two hours, you will learn to spot the flaws in typical designs that make e-learning deathly boring and you will be able to fix them. Ready? |

Remember the more fully learners recognize and value the advantages of learning the material at hand, the more effective the material will be. But if you agree on this point, you might wonder whether a textual listing of objectives is really the best way to sell anyone on learning. Good question. Yes, we can do better.

Don't List Objectives

Don't List Objectives

If learners aren't going to read objectives, even valuable and well-written objectives, listing them at the beginning of each module of instruction isn't a very useful thing to do. In fact, it may do more harm than good since it communicates to learners from the beginning that yours will be just another typical boring e-learning experience.

In e-learning, we have techniques for drawing attention to vital information. We use interactivity, graphics, and animation—in short, all the powers of interactive multimedia—to help learners focus on beneficial content. Why, then, shouldn't we use these same powers to portray the objectives and sell the learning opportunity to the learner?

Instead of just listing the objectives, provide meaningful and memorable experiences.

Example 1: Put the Learner to Work

Perhaps the clearest statement of possible outcomes comes from setting the learner to work immediately on a stated task. If learners try and fail, at least they'll know what they are going to be able to do when they complete the learning far more clearly than they could glean from reading a list of objectives.

In this award-winning example, Expedia needed to train all their phone-based customer service representatives on a vast amount of travel knowledge for every major city in the United States. Traditional methods of informative presentations with assessments had not been effective, leading Expedia to a learner-centric design focused on the authentic on-the-job activities trainees could expect to perform. The content ranged from information about local attractions to neighborhood characteristics, hotels, and transportation choices. (See Figure 10.3.)

Figure 10.3 A meaningful task challenge takes the place of traditional learning objectives.

Let's walk through the example. Learners are presented with a series of customers who wish to book a dream vacation. The performance task requires learners to choose the best lodging, attractions, activities, and transportation based on simulated customers profiles and preference-revealing quotes. (See Figure 10.4.)

Figure 10.4 Jumping right in: The initial activity is interesting and authentic.

To find the best lodging choice, a comprehensive list of neighborhoods is presented with descriptions. Each neighborhood contains a number of hotels, at least one of which matches the customer needs and preferences. Other categories contain simple lists with item descriptions that provide sufficient information to match specific needs/wants. (See Figure 10.5.)

Figure 10.5 Listening carefully: Learners need to take cues from the customer's profile and comments.

Once the entire trip has been planned, the learner receives a comment card with customer feedback. (See Figure 10.6.)

Figure 10.6 Consequences provide memorable feedback.

The learner must then correct all problems with the trip until the customer is completely satisfied. (See Figure 10.7.)

Figure 10.7 A personal thank-you provides effective rewards.

At that point, another customer calls in with different needs and preferences. Once learners have repeated enough exercises, they have much higher prospects of getting a trip right on the first try. A trip planned successfully on the first try is quite rewarding. This learner-centric design with multiple scenarios effectively motivates learners to familiarize themselves with each neighborhood, hotel, attraction, and so forth during the pursuit of the perfect vacation.

You might be concerned that some failures, especially early on, will frustrate or demoralize learners. It is always an appropriate concern that initial challenges may produce more negative frustration than positive motivation. Interactive features must be provided to protect learners from becoming overwhelmed and discouraged. Either the software and/or the learner must be able to adjust the level of challenge when appropriate. Please see Magic Key 2 for a discussion of risk management.

Example 2: Drama

Motivation is not an exclusively cognitive process. Motivations involve our emotions and our physiological drives, as well. Good speakers, writers, and filmmakers are able to inspire us to take action, to reevaluate currently held positions, and to stir emotions that stick with us to guide future decisions.

Imagine this scenario. Airline mechanics are to be trained in the process of changing tires on an aircraft in its current position at a gate. You can easily imagine the typical first page of the training materials to read something like this:

Now imagine this approach:

You press a key to begin your training. Your computer screen slowly fades to full black. Lightning crashes and your screen flickers bright white a few times. You see a few bolts of lightning between the tall panes of commercial windows just barely visible. Through the departure gate window, you see an airplane parked at the gate. The rain is splashing off the fuselage. A gust of wind makes a familiar threatening sound.

The scene cuts to two men in yellow rain slickers shouting at each other to be heard over the background noise of the storm and airport traffic.

“You'll have to change that tire in record speed. The pilot insists there's a problem, and that's all it takes. We have to change it. There's going to be a break in the storm and there are thirty-some flights hoping to get out before we'll probably have to close down again.”

“No problem, Bob. We're on it.” Return to the windows, where we now see people at the gate—a young man in business attire is pacing worriedly past an elderly woman seated near the windows.

“Don't worry, young man. They won't take off if the storm presents a serious danger. Even in a storm and with all the possible risks of air travel, I still think it's the safest way for me to get around.”

“Oh, thanks, ma'am. But you see, my wife is in labor with our first child. I missed an earlier flight by ten minutes, and now this is the last one out tonight. I'm so worried this flight will be delayed for hours—or worse, even cancelled due to weather. I'm not sure what my options are, but I need to get home tonight.”

Back outside, Bob runs up to three mechanics as they run toward him in the rain.

“All done, Bob. A little final paperwork inside where it's dry, and she's set to fly.”

“Your team must have set a record. Even under pleasant circumstances, I don't know any other employees who could have done such a good job so fast. The departure of this aircraft won't be delayed one minute because of that tire change. A lot of people will benefit from your work tonight.

“This is going to headline the company's newsletter!”

I hope you can see how this dramatic context can much more effectively communicate the learning objectives and motivate learners to pursue them. Who wouldn't want to be a hero in this circumstance? Who wouldn't begin thinking, “I'll bet I could learn to do that…maybe even do it better.” And, then, “I wonder what it takes. Hope I get a chance to find out in this learning program.”

An emotion-arousing motivational event like this can be done through everything from a few stick figures with audio to a full fidelity video of professional mechanics or actors. The expense can be kept small, yet the benefit to performance and learning can be invaluable.

Magic Key 2: Put the Learner at Risk

Magic Key 2: Put the Learner at Risk

When do our senses become most acute? When are we most alive and ready to respond?

It's when we are at risk. It's when we sense danger (even imagined danger) and must make decisions to avert it and protect ourselves. It's when we see an opportunity to win accompanied by the possibility of losing.

Games energize us primarily by putting us at risk and rewarding us for success. Although it's easy to point to the rewards of winning as the allure, it is also the energizing capabilities of games that make them so attractive. It feels good to be active, win or lose. Risk makes games fun to play.

Proper application of risk seems to provide optimal learning conditions. I used to think, in fact, that putting learners at some level of risk was the only effective motivator worth considering in e-learning and the most frequently omitted essential element. Although I have identified other essential powerful motivators—the other Magic Keys—I continue to believe that risk is the most effective in the most situations. There are pros and cons, however (see Table 10.4).

Table 10.4 Risk as a Motivator

| The Positives | The Negatives |

| Energizes learners, avoids boredom | May frighten learners, causing anxiety that inhibits learning and performance |

| Focuses learners on primary points and on performance | May rush learners to perform and not allow enough time to build a thorough understanding |

| Builds confidence in meeting challenges through rehearsed success | May damage confidence and self-image through a succession of failures |

Problems with Risk as a Learning Motivator

Consider instructor-led training for a moment. In the classroom, putting the learner at risk can be as simple as the instructor posing a question to an individual learner. The risk of embarrassment goes far beyond failing to answer correctly. Public performance can affect social status, social image, and self-confidence for better or worse. Even if we're in a class in which we know none of our classmates, being asked a question typically causes a rush of adrenaline because of what's at stake.

Competition is a risk-based device used by many classroom instructors to motivate learners. In some of my early work with PLATO, I managed an employee who considered one of PLATO's greatest strengths to be its underlying communication capabilities that were able to pit multiple learners against one another in various forms of competitive interplay. Although these capabilities were often used just for gaming, he was intrigued with the idea of using them to motivate learners.

Competitive e-learning environments can certainly be created, but, unfortunately, pitting learners against one another may create a counter-productive win/lose environment. It may be true that even the losers are gaining strengths, and they may be effectively motivated to do their best as long as the situation or their competitors don't overly intimidate them. Anonymity can help. But it's difficult to prevent nonwinners from seeing themselves as losers. As one axiom puts it:

As trainers, our goal is to make all learners winners. And to that end, we need learners focusing on skill development, not each other.

Private versus Social Learning Environments

There are advantages to being in the company of others when we learn. We are motivated to keep up with other learners and benefit from their questions. We learn from watching the mistakes and successes of others. Communication with others helps round out our understanding. In addition, successful public performance gives us confidence—a performance attribute that can be lacking when learning and practice take place only in private.

However, the risk of public humiliation causes, for many, an immediate and unpleasant rush of adrenaline. While a successful public performance can easily meet our two essential criteria of being a meaningful and memorable learning event, the event may be memorable because of the fear associated with it. And although traumatic experiences may be memorable, the emotional penalty is too high. For many individuals, practice in a private environment avoids all risk of humiliation and can bring significant learning rewards.

Interestingly, research finds people respond to their computers as if they were people (Reeves and Nass, 1999). We try to win the favor of our computers and respond to compliments extended to us by software. Quite surprisingly, solo learning activities undertaken with the computer have more characteristics of social learning environments than one would expect. Talented instructional designers build personality into their instructional software to maximize the positive social aspect of the learning environment.

Asynchronous electronic communications, such as e-mail, and synchronous learning events, such as are now possible with various implementations of remote learning, can build a sense of togetherness. Where resources are available to assist learning through such technologies, a stronger social learning environment can be offered, although in this case, just as with other forms of e-learning, design of learning events, not the mere use of technology, determines the level of success achieved.

For many organizations, though, one of the greatest advantages of e-learning comes from its constant availability. When there's a lull in their work, employees can be building skills rather than unproductively waiting for more work assignments or scheduled classes to roll around. Instant availability and the possibility of spending whatever time happens to be available whenever it is available are important benefits of e-learning. Unless you can count on the availability of appropriate colearners at all times, it is probably best to design independent learning opportunities at least for a good share of your learning events.

Don't Baby Your Learners

Don't Baby Your Learners

Some organizations are very concerned about frustrating learners, generating complaints, or simply losing learners because they were too strongly challenged. They are so concerned, in fact, that they make sure learners are unlikely to make mistakes. Learners can cruise through the training, getting frequent rewards for little accomplishment.

The organization expects to get outstanding ratings from learners on surveys at the end of riskless courses, and may indeed get them even if no significant learning occurred (Thalheimer, 2016). But even better ratings may be achieved by actually helping learners improve their skills. More importantly, both individual and organizational success might be achieved. A lot is learned from making mistakes. And people like overcoming challenges! Look at how many people go back to the golf course week after week and spend a fair amount of money for the privilege of overcoming challenges.

Go ahead, break the rules and put learners at some measure of risk. Then provide structures that avoid the potential perils of doing so. Here are some suggestions:

Avoiding Risk Negatives

The advantages of risk are great, but they don't always outweigh the negatives. Fortunately, the negatives can be avoided in almost every instance, so that we're left only with the truly precious positive benefits. Effective techniques include:

- Allowing learners to ask for the correct answer. If learners see they aren't forced into a risk and can back out at any time, learners often warm up to taking chances, especially when they see the advantages of doing so.

- Allowing learners to set the level of challenge. Low levels of challenge become uninteresting with repetition. Given the option, learners will usually choose successively greater challenges.

- Complimenting learners on their attempts. Some encouragement, even when learner attempts are unsuccessful, does a lot to keep learners trying. It is important for learners to know that a few failures here and there are helpful and expected.

- Providing easier challenges after failures. A few successes help ready learners to take on greater challenges.

- Providing multiple levels of assistance. Instead of all or nothing, learners can ask for and receive help ranging from general hints to high-fidelity demonstrations.

Using these techniques, it is possible to offer highly motivating e-learning experiences with almost none of the typical side effects that accompany learning risk in other environments.

Staying Alive

Why do kids (and adults) play video games for hours on end? Shortly after home versions of games like the classic Super Mario Bros. became available, our son and all the children on our block knew every opportunity hidden throughout hundreds of screens under a multiplicity of changing variables. They stayed up too late and would have missed meals, if allowed to, in order to find every kickable brick in walls of thousands of bricks (see Figure 10.8). They learned lightning-fast responses to jump and duck at exactly the right times in hundreds of situations. And for what? Toys? Money? Vacations? Prizes? Nope.

Figure 10.8 Computer games successfully teach hundreds of facts and procedures.

We play these games as skillfully as possible for the reward of being able to continue playing, to see how far we can get, to avoid dying and having to start over, to feel good about ourselves, and to enjoy the energy of a risky, but not harmful, situation.

In the process of starting over (and over, and over), we practice all the skills from the basics through the recently acquired skills, overlearning them in the process and becoming ever more proficient. We take satisfaction in confirming our abilities as our adrenaline rises in anticipation of reencountering the challenges that doomed us last time.

Imagine, in contrast, the typical schoolteacher setting out to teach students to identify which bricks hide award points. There would be charts of the many thousands of bricks in walls of various configurations. You can just imagine the homework assignments requiring students to memorize locations by counting over and down so many bricks and circling the correct ones. Students would be so bored that behavior problems would soon erupt.

The teacher would earnestly remind students that someday in the future, they would be glad they could identify the bricks to kick. Great success would come to those learners who worked diligently to pinpoint all the correct bricks. After several years of pushing groups of students through these exercises, a bored teacher might turn to e-learning for help. With a happy thought of transferring the teaching tedium to the computer, the teacher would likely create an online version of the same grueling instructional activities.

To me, this sounds similar to a lot of corporate training. Although we might not see our trainees pulling one another's hair, making crude noises, and writing on desks, we can be sure they will be checking e-mail, catching up on social media, and even ordering holiday gifts online when learning tasks are so uninteresting.

Just teaching one task within the complex behaviors of the venerable Super Mario Bros. player would be a daunting challenge for many educators; yet, millions of people have become adroit at these tasks with no instruction—at least with no typical instruction. Why aren't these obviously effective instructional techniques applied to e-learning, with all its interactive multimedia capabilities?

Good question. Why not, indeed!

Repetition and Goals

Repetition through practice is a primary way of preventing memory loss (see Figure 10.9). Although strong stimuli, such as traumatic and emotionally charged events, can stick with us without repetition, new information and skills often require rehearsing.

Figure 10.9 Learning through rehearsal

The good news is that e-learning is a perfect medium for practice, having infinite patience and the ability to retrieve practice exercises from a pool if not to actually generate as many exercises as may be needed.

The bad news is that practice is often boring. Think of all the things we cajole our children into practicing as they grow up: alphabet, multiplication tables, notes of the base and treble clef, spelling, etc. We often search for more ways to get kids to practice and have to get creative in our methods. And this is exactly what we must do in e-learning design as well.

This is where goals come in. By establishing performance goals, we draw attention away from repetition and toward results—the progress toward goal achievement. If learners fail over and over again, they will generally want to stop. But by setting increasingly challenging goals, learners will receive interim and practice-sustaining rewards. Visible progress keeps learners trying.

Adding risk into such a framework is rather straightforward and can increase motivation to persevere to a level of mastery. Having incremental goals, perhaps the most obvious means of harnessing risk is to limit the number of attempts permitted at each advanced level before setting the learner back a level.

Let's look at a very successful example.

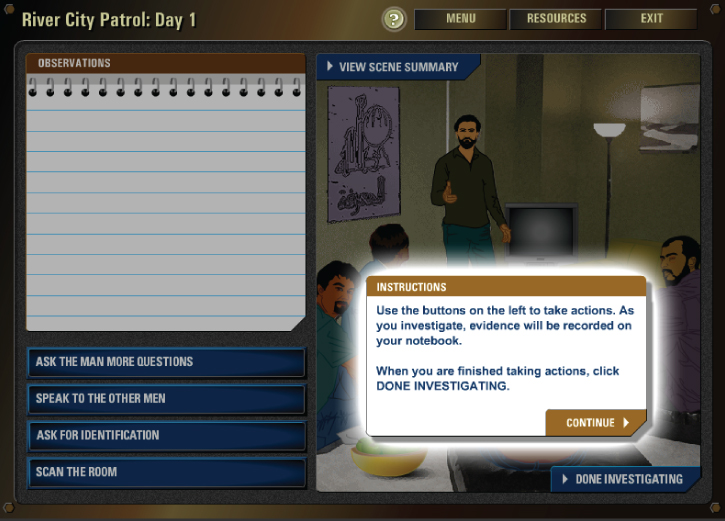

Learners are put to “work” almost immediately not just to make the learning active but also as a means of determining the right level of challenge and practice needed for each learner (see Figure 10.10).

Figure 10.10 Alert to active learning appears even in the initial screen.

Adequate but minimal instruction is given so learners can begin showing what they know, can, and can't do almost immediately (see Figures 10.11 and 10.12). The amount of instruction and the level of challenge adapt to the learner throughout.

Figure 10.11 Active learning begins almost immediately.

Figure 10.12 A quick performance-monitored walkthrough leads to more detailed instruction only if needed.

As learners progress, the variety and number of items needing to be served simultaneously increases. In Figure 10.13, the apprentice cook is facing “Challenge 4” which includes a total of six items, three for each of two plates. All items are cooking and this learner was smart enough to align cooking items to plates to minimize having to spend time rechecking tickets when it becomes time to plate. Customer wait time is shown and keeps the pressure on.

Figure 10.13 Challenge levels advance to demand authentic skilled performance.

Because each food item requires a different amount of cooking time, all six items will be ready to plate together only if they started cooking in the proper sequence and were timed properly. The cook will then need to get items to the plates quickly enough to prevent those items still cooking from burning and those items plated from getting cold.

There are many ways to fail a challenge, and for most people a considerable amount of practice is necessary to reach and meet the final goal. Feedback (see Figure 10.14) is detailed after each challenge is completed or time runs out.

Figure 10.14 Feedback notes all errors specifically and indicates this learner can try this level again.

Resources are available for learners. They inform how to cook each item and how long. Learners can reference the information between challenges and even during them, but if referenced during a challenge, cooking items may burn if in progress while the learner is away. To increase the risk of burned items or unacceptably slow service, when learners return to the kitchen from looking up information, they find a delaying mess of broken eggs to pick up (Figure 10.15). “Oh, no!” Learners are effectively encouraged to internalize critical information rather than looking everything up as they try to cook.

Figure 10.15 Challenge levels advance to demand authentic skilled performance.

Learners are given only a couple of chances to succeed at each level. The major risk is that multiple failures will produce the dreaded black screen (Figure 10.16) and set the learner back a level where it's necessary to work back up. It's even possible that the learner will regress more than one level and need to climb back up through continuous successes.

Figure 10.16 The risk of dropping down a level is a constant motivator.

This use of risk is amazingly effective in getting learners to practice. Learners witness that just knowing what to do isn't nearly enough to perform successfully and that practice really is necessary. But practice can be fun and very much is in this e-learning. Whether relevant or not to them personally, we've found almost everyone who gives this lesson a try feels compelled to reach and succeed at the top level. But it's unlikely you'll get there without some intensive practice.

Magic Key 3: Select the Right Content for Each Learner

Magic Key 3: Select the Right Content for Each Learner

What's Boring?

Long presentations of information you already know, find irrelevant, or can't understand.

What's Interesting?

- Learning how your knowledge can be put to new and valuable uses

- Understanding something that has always been puzzling (such as how those magicians switch places with tigers)

- Seeing new possibilities for success

- Discovering talents and capabilities you didn't know you had

- Doing something successfully that you've always failed at before

Moral? It's not enough for learners to believe there is value in prospective instruction (so that they have sufficient initial motivation to get involved). There must also be real value to sustain the required engagement. The content must fit with what they are ready to learn and capable of learning.

Individualization

From some of the earliest work with computers in education, there has been an alluring vision: a vision that someday technology would make practical the adaptation of instruction to the different needs of individual learners. Some learners grasp concepts easily, whereas others need more time, more examples, more analogies, or more counterexamples. Some can concentrate for long periods; others need frequent breaks. Some learn quickly from verbal explanations, others from graphics, and others from hands-on manipulation. The vision saw that, while instructors must generally provide information appropriate to the needs of the average learner, technology-delivered instruction could vary the pacing and selection of content as dictated by the needs of each learner.

Not only could appropriate content be selected for each learner's goals, interests, and abilities, but instruction could also be adapted to interests, cultural backgrounds, and even personal lifestyles.

Perhaps no instructional path would ever be the same for two learners. It would be possible for some learners to take cross-discipline paths, whereas others might pursue a single topic in great depth before turning to another topic. Some learners would need to keep diversions to a minimum as they worked on basic skills; others would benefit from putting basic skills into real-life contexts almost from the beginning. Areas of potential individualization seemed almost endless and possible. And given enough learners across which to amortize the cost of development, the individualization could be quite affordable.

Many classroom instructors do their best to address individual needs, but they know there are severe limits to what they can do specifically for individual learners, especially when there are high levels of variation among learners in a class. The pragmatic issues of determining each learner's needs, constructing an individual road map, and communicating the plan to the learner are insurmountable even without considering the mainstay of the typical instructor's day: presenting information. It's difficult to handle more than a small number of learners in a highly individualized program without the aid of technology. With e-learning, we do have the technology necessary for truly exciting programs that can adapt effectively to the needs of individual learners. Through technology, the delivery and support of a highly individualized process of instruction is quite practical, and there are actually many ways instruction can be fitted to individual needs.

Fortunately, it's not necessary to get esoteric in the approach. The simplest individualized approaches contribute great advantages over one-size-fits-all and often have the greatest return on investment. They may require an expanded up-front investment, of course, as there's hardly anything cheaper than delivering one form of the curriculum in the same manner to many learners at the same time. But there are some practical tactics that result in far more individualized instruction than is often provided.

Let's look at some alternative paradigms to see how instruction has been individualized. Our emphasis here will be on just one parameter—content matching. Efforts to match preferences, psychological profiles, and other learner characteristics are technically possible. But where we haven't begun to match content to individual needs, we'll hardly be ready for the more refined subtleties of matching instructional approaches to learners.

Common Instruction

The most prevalent form of instruction does not attempt to adapt content to learners. Learners show up (Figure 10.17). The presentations and activities commence. After a while, a test is given and grades are issued. Tell, test, grade. Done. Next class, please.

Figure 10.17 Common instruction paradigm.

This common form of instruction has been perpetrated on learners almost since the concept of organized group instruction originated. It's as simple and inexpensive as you can get, and it's credible today not because of its effectiveness but because of its ubiquity.

It's unfortunate that so many use common instruction as a model for education and training. This tell-and-test paradigm is truly content-centric. With honorable intentions and dedication, designers frequently put great effort into the organization and presentation of content and sometimes into preparation of test questions, but they do nothing to determine the readiness of learners or the viability of planned presentations for specific individuals. Consequently, although the application easily handles any number of learners and has almost no administrative or management problems, it doesn't motivate the learner.

The effectiveness of common instruction ranges widely, depending on many factors that are usually not considered, such as motivation of learners, their expectations, their listening or reading skills, their study habits, and their content-specific entry skills (Figure 10.18). It is often thought that the testing event and grading provide sufficient motivation, so the issue of motivation is moot. Besides, motivation is really the learners' problem, right? If they don't learn, they'll have to pay the consequences—and hopefully will know better next time.

Figure 10.18 Individualization rating for common instruction.

Wrong thinking, at least in the business world. It's the employer and the organization as a whole who will pay the consequences—consequences that are far greater than most organizations recognize.

Selective Instruction

Selective instruction adds a front end filter to common instruction. The front end is designed to improve effectiveness of the legacy common instruction by narrowing the range of learners to be taught. Clever, huh? Change the target audience rather than offer better instruction.

Most American colleges and universities employ selective instruction at an institutional level; that is, they select and prepare to teach only those learners who meet minimum standards. Students are chosen through use of entry examinations, measures of intellectual abilities, academic accomplishments, and so on. The higher those standards can be, the better the outcomes will be.

It makes sense that learners who have been highly successful in previous common instructional activities will deal effectively again with common instruction's unfortunate limitations. Organizations of higher learning will, therefore, find their instructional tasks simplified. They need to do little in the way of motivating learners and adapting instruction to individual needs. They can just find bright, capable, energetic learners, and then do whatever they want for instruction. The learners will find a way to make the best of it and learn—at least enough to pass a test at the end of the course.

It dismays me that our most prestigious institutions boast of the high entrance examination scores achieved by their entering learners. What they know, but aren't saying, is that they will have few instructional challenges, and their learners will continue to be outstanding performers. By turning away learners with lower scores, they will have far less challenging instructional tasks and will be able, if they wish, to devote more of their time to research and publishing. They actually could, if they wished (and I don't mean to suggest that they do), provide the weakest instructional experience and still anticipate impressive learning outcomes.

Figure 10.20 Individualization rating for selective instruction.

We do need organizations that can take our best learners and move them to ever-higher levels of achievement. But perhaps the more significant instructional challenges lie in working with more typical learners who require greater instructional support for learning. Here, common instruction probably has been less effective than desired and should be supplanted by instruction that is based more on our knowledge of human learning than on tradition.

Remedial Instruction

Recognizing that issuing grades is not the purpose of training, some have tried modifying common instruction to help failing learners. In this remedial approach, when testing indicates that a learner has not reached an acceptable level of proficiency, alternate instructional events are provided to remedy the situation.

These added events, it is hoped, will bring failing learners to an acceptable level of performance.

Remediation is something of an advance toward purposeful instruction, because, rather than simply issuing grades, it attempts to help all learners achieve needed performance levels.

If learners fail on retesting, it is possible to continue the remediation, perhaps by providing alternate activities and support, until they achieve the required performance levels.

One has to ask, if the remediation is more likely to produce acceptable performance, why isn't it provided initially? The answer could be that it requires more instructor time or more expensive resources. If many learners can succeed without it, they can move on while special attention is given to the remedial learners.

The unfortunate thing about remedial instruction is that its individualization is based on failure. Until all the telling/testing is done, instructors may not discover that some learners are inadequately prepared for the course, or don't have requisite language skills, or aren't sufficiently motivated. Although more appropriate learning events can be arranged after testing reveals individual problems, precious time may have been wasted. The instructor and many learners (including those for whom the instruction is truly appropriate) may have been grievously frustrated, and remedial learners may be more confused and more resistant to learning in their reluctance to have more experiences of failure.

Figure 10.22 Individualization rating for remedial instruction.

All in all, remediation represents better recognition of the true goals of instruction, but employs a less-than-optimal process of reaching them.

Individualized Instruction

The same components of telling, testing, and deciding what to do next can be re-sequenced to achieve a remarkably different instructional process. As with so many instructional designs, a seemingly small difference can create a dramatically different experience with consequential outcomes.

A basic individualized system begins with assessment. The intent of the assessment is to determine the readiness of learners for learning with the instructional support available. Learners are not ready if, on the one hand, they already possess the competencies that are the goal of the program, or, on the other hand, they do not meet the necessary entry requirements to understand and work with the instructional program. Unless assumptions can be made accurately, as is rarely the case despite a common willingness to make assumptions regarding learner competencies, it's very important to test for both entry readiness and prior mastery.

Record keeping is essential for individualized programs to work, because progress and needs are frequently reassessed to be sure the program is responding to the learner's evolving competencies. Specific results of each testing event must be kept, not just as an overall performance score but also as a measurement of progress and achievement for every instructional objective each learner is pursuing.

As progress is made and records are updated, the questions of readiness and needs are posed. If there are (or remain) areas of weakness in which the training program can assist, learning activities are selected for the individual learner. Any conceivable type of learning activity that can be offered to the learner can be selected including workbook exercises, group activities, field trips, computer-based training, videos, and so on.

The individualized learning system is greatly empowered if alternate activities are available for each objective or set of objectives. Note that it is not necessary to have separate learning activities available for each objective, although it helps to have some that are limited to single objectives wherever possible. An arrangement suggested by Table 10.5 would be advantageous and perhaps typical. However, great variations are workable; it is often possible to set up an individualized learning program based on a variety of existing support materials.

Table 10.5 Learning Resource Selection

| Learning Resources | ||||||

| A Basics Manual |

B Basics Manual |

C Introductory Video |

D Blog on Recent |

E Tutorial on Problem |

F Group Discussion |

|

| Objective | Text in | Exercises in | Discoveries | Solving | on Science | |

| Number | Chapter 1 | Chapter 1 | ||||

| 1 | X | X | ||||

| 2 | X | X | ||||

| 3 | X | X | X | |||

| 4 | X | X | ||||

Looking at Table 10.5, you can see how an individualized learning system works. If a learner's assessment indicated needed instruction on all four objectives, what would you suggest the learner do? You'd probably select resources A and D, because we don't happen to have one resource that covers all four and because together A and D provide complete coverage of the four objectives.

Further, to the learner's benefit, these two resources cover more than one objective each. When resources cover multiple objectives, it is more likely that they will discuss how various concepts relate to one another. Such discussions provide bridges and a supportive context for deeper understanding. Some supportive context, particularly important for a novice, is likely to be there in the selection of A and D in the preceding example, whereas it would be less likely in the combination of C, B, and F.

Just as with remedial instruction, if a prescribed course of study proves unsuccessful, it's better to have an alternative available than to send the learner simply back to repeat an unsuccessful experience. If the learner assigned to A and D were reassessed and still showed insufficient mastery of Objective 3, it would probably be more effective to assign Learning Resource E at this point than to suggest repetition of D.

The closed loop of individualized instruction systems returns learners to assessment following learning activities, where readiness and needs are again determined. Once the learner has mastered all the targeted objectives, the accomplishment is documented, and the learner is ready to move on.

The framework of individualized instruction is very powerful, yet, happily, very simple in concept. Its implementation can be extraordinarily sophisticated, as is the case with some learning management systems (LMSs) or learning content management systems (LCMSs), whether custom-built or off the shelf. However, it can also be built rather simply within a single instructional application and have great success.

Note that this structure does not require all learners to pursue exactly the same set or the same order of objectives. Very different programs of study are easily managed. Learners who require advanced work in some areas or reduced immersion in others are easily accommodated (Figure 10.24).

Figure 10.24 Framework of individualized instruction adapts to job requirements.

Figure 10.25 Individualization rating for individualized instruction.

Practical Solutions

As we have noted, there is a continuum of individualization. Some individualization is more valuable than none, even if the full possibilities of individualized instruction are beyond reach for a particular project. One of the most practical ways of achieving a valuable measure of individualization is simply to reverse the paradigm of tell and test in common instruction.

Fixed Time, Variable Learning

With the almost-never-appropriate tell-and-test approach, exemplified by prevalent instructor-led practices, learners are initially told everything they need to know through classroom presentations, textbooks, videotapes, and other available means. Learners are then tested to see what they have learned (more likely, what they can recall). After the test, if time permits (since instructor-led programs almost always work within a preset, fixed time period, such as a week, a quarter, or a semester), more telling will be followed by more testing until the time is exhausted (Figure 10.26). The program appears well planned if a final test closely follows the final content presentation, just before the time period expires.

Figure 10.26 Tell and test.

When e-learning follows this ancient plan, the plan's archaic weaknesses are preserved.

Fixed Content, Variable Learning

Similarly, instead of a predetermined time period, content coverage can be the controlling factor. Just like above, the process of alternately telling and testing is repeated until all the content has been exhausted. The program then ends.

To emphasize the major weakness of this design (among its many flaws), the tell-and-test approach is often characterized as fixed time, variable learning—or, in the case of e-learning implementations, fixed content, variable learning. In other words, the approach does not ensure sufficient learning to meet any standards. It simply ensures that the time slot will be filled or that all the content will be presented.

Fixed Learning, Variable Time and Content

To achieve success through enabling people to do the right thing at the right time, we are clearly most interested in helping all learners' master skills. It is not our objective simply to cover all the content or fill the time period. To get everyone on the job and performing optimally as quickly as possible, we would most appropriately choose to let time vary, cover only needed content, and ensure that all learners had achieved competency.

Put the Test First

Many instructional designers embark on a path that results in tell-and-test applications. They may disguise the underlying approach rather effectively, perhaps by the clever use of techno-media, but the tell-and-test method nevertheless retains all the weaknesses of common instruction and none of the advantages of individualized instruction.

Many instructional designers embark on a path that results in tell-and-test applications. They may disguise the underlying approach rather effectively, perhaps by the clever use of techno-media, but the tell-and-test method nevertheless retains all the weaknesses of common instruction and none of the advantages of individualized instruction.

Let's compare the tell-and-test and test-and-tell methods (see Table 10.6). The advantages gained by simply putting the test first and allowing learners to ask for content assistance as they need it are amazing. As previously noted, just a slight alteration of an instructional approach often makes a dramatic difference. This is one of those cases. There is very little expense or effort difference between tell-and-test on the one hand and test-and-tell on the other, but the learning experiences are fundamentally different.

Table 10.6 Selecting Content to Match Learner Needs

| Tell and Test | Test and Tell |

| Because they have to wait for the test to reveal what is really important to learn (or it wouldn't be on the test), learners may have to guess at what is important during the extended tell time. They may discover too late that they have misunderstood as they stare at unexpected questions on the test that will determine their grades. | Learners are immediately confronted with challenges that the course will enable them to meet. Learners witness instantly what they need to be learning. |

| All learners receive the same content presentations. | Learners can skip over content they already know as evidenced by their initial performance. |

| Learners are passive, but they try to absorb the content slung at them, which they hope will prove to be empowering at some point. | Learners in well-designed test-and-tell environments become active learners; they are encouraged to ask for help when they cannot handle test items. The presentation material (which can be much the same as that used in tell and test) is presented in pieces relevant to specific skills. Learners see the need for it and put it to use. |

| It's boring. | Not likely to be boring. |

Getting novice designers to break the tendency to begin their applications with a lot of presented information (telling) is not simple. Indeed, almost everyone has the tendency to launch into content presentation as the natural, appropriate, and most essential thing to do. I have been frustrated over the years as my learners and employees, especially novices to instructional design, have found themselves drawn almost magnetically to this fundamental error. I have, however, discovered a practical remedy: After designers complete their first prototype, I simply ask them to switch it around in the next iteration. This makes content presentations available on demand and subject to learner needs.

This example, drawn from e-learning initiatives at the National Food Services Management Institute, illustrates the power of the test-and-tell technique to select the right content for each learner, and avoids instruction on principles some learners may already know. Cooking with Flair: Preparing Fruits, Salads, and Vegetables teaches a range of facts and procedural information regarding the preparation of fruits and vegetables. The target learners usually have some general but incomplete knowledge of the topics to be covered, and the gaps in their knowledge can vary greatly. A typical strategy in such a context is to tell everybody everything, regardless of whether or not they need it. This is rarely helpful, as learners tend to stop paying attention when forced to read information that they already know or, on the other end of the scale, that they can't understand.

This is exactly the type of situation in which test-and-tell is most powerful.

We'll look at a module called “Do the Dip!,” in which learners are to master how to keep freshly cut fruit from turning brown (Figure 10.28). The principle at hand: fruits that tend to darken should be dipped in a dilute solution of citrus juice, while other fruits do not need to be treated in this way. The learner is to learn how this principle affects common fruits. The setup here is very simple. Learners are given a very brief statement that sets the context. Then, they are immediately tasked with the job of preparing a fruit tray. They can place the cut fruit directly on the serving tray, or they can first dip the fruit in a dilute solution of lemon juice.

Figure 10.28 Do the Dip!: Learners must decide whether or not it is appropriate to dip fruit when preparing a fresh fruit tray.

Source: Cooking with Flair: Preparing Fruits, Salads, and Vegetables. Courtesy of National Food Service Management Institute, University of Mississippi.

If the user correctly dips a fruit, the information regarding that choice is confirmed with a message and a Do the Dip! flag on the fruit (Figure 10.29). Whether the learner already knew the concept or guessed correctly, the “tell” part of the instruction is contained in the feedback—presented after the learner's attention has been focused by the challenge.

Figure 10.29 Correct responses are reinforced with a Do the Dip! stamp on selected fruit.

How about when the learner is wrong? When a fruit is not dipped when it should be, the fruit turns brown and unappealing, while instructional text specific to the error is presented on the screen (Figure 10.30).

Figure 10.30 Incorrect responses result in brown, unappealing fruit.

After the exercise is complete, the learner is given a summary screen: a complete and attractive fruit platter and screen elements that further reinforce the lesson of which fruits require a citrus treatment (Figure 10.31).

Figure 10.31 Success results in a completed platter and reminders posted on each fruit.

This is a small and straightforward application of the test-and-tell principle, used to select what information to present to the learner and when simply to confirm the learner's present knowledge and skills. You should notice this magic key in action in more sophisticated ways in nearly every other example described in this book. It's engaging, efficient, and effective.

Nonetheless, a common response from instructional designers is, “Isn't it unfair to ask learners to do a task for which you haven't prepared them?” (Interestingly, we rarely if ever hear this complaint from actual students.) But it really isn't unfair at all. Quite the reverse: The challenge focuses learning attention to the task at hand, allows capable learners to succeed quickly (saving time and frustration), provides learning content to the right people at the right time, and motivates all learners to engage in critical thinking about a task instead of simply being passive recipients of training. When the “tell” information is presented in the context of a learner action (i.e., right after a mistake), learners are in an optimal position to assimilate the new information meaningfully into their existing understanding of the topic.

Magic Key 4: Use an Appealing Context

Magic Key 4: Use an Appealing Context

Learning contexts have many attributes. The delivery system is one very visible attribute, as is the graphic design or aesthetics of an e-learning application. More important than these, however, are the role the learner might be asked to play, the relevance and strength of the situational context, and the dramatic presentation of context.

It's easy to confuse needed attributes of the learning context with ornaments and superfluous components. Unfortunately, such confusion can lead to much weaker applications than intended. However, a strong learning context can amplify the unique learning capabilities of e-learning technologies. Let's first look at some mistakes that have continued since the early days of e-learning.

The Typing Ball Syndrome

When I did my first major project with computer-based instruction, it was with computer terminals connected to a remote IBM 360 central computer. The terminals were IBM 3270s, which had no display screen but were more like typewriters, employing an IBM Selectric typewriter ball.

Continuous sheets of fanfold paper were threaded into the machine. A ball spun and tilted almost magically to align each character to be typed. With thin, flat wires manipulating the ball's mechanism, the ball, like a mesmerized marionette, hammered the typewriter ribbon to produce crisp, perfectly aligned text.

Selectric typewriters were something of an engineering fascination.

They so quickly produced a clean, sharp character in response to a tap on the keyboard, it was hard to see the movement. And yet, since a perfect character appeared on the paper, you knew the ball had spun to precisely the correct place and had tapped against the ribbon with exactly the right force.

If the Selectric typewriter was fascinating, the IBM 3270 terminal was enthralling. Its Selectric ball typed by itself like a player piano! Looking very much like the Selectric typewriter with a floor stand, the terminal was able to receive output from a remote computer and could type faster than any human. The keys on the keyboard didn't move. The ball just did its dance while letters appeared on the paper.

The computer could type out information and learners could type their answers, to be evaluated by the computer. The technology was fascinating. There was much talk about this being the future of education.

It felt like classroom delivery of instruction was near the end of its life span, and, despite fears of lost teaching jobs, there was great excitement that private, personalized learning supported by amazingly intelligent computers would truly make learning fun and easy.

Novelty versus Reality

There were some very positive signs that technology-led instruction would indeed be a reality in the near future. Learners eagerly signed up for courses taught with the use of computer terminals. Seats filled up rapidly, requiring dawdling learners to sign up for traditionally taught classes or wait another term to see if they would be lucky enough to get into one of the computer-assisted classes.

But some disturbing realities crept in, realities that countered initial perceptions and rosy predictions. For one thing, it took a lot longer for information to be typed out than to find it in a book. While you didn't get to watch them being typed, books are pretty fast at presenting information—and they are portable, too. They don't make any noise, either—so they can be used in libraries and other quiet places that are conducive to study. They often include graphics and visual aids—things our Selectric typewriters couldn't provide. You can earmark a page and easily review. You can skim ahead to get some orientation and get a preview of what was to come.

Learners, the harsh but insightful critics that they often are, did the most unexpected thing. Instead of sitting at the terminals waiting for the typing ball to spit out text, they simply took their “borrowed” copies of printouts to a comfortable location and studied them. Sometimes they'd work together in pairs or groups: Using just the printout, one learner would read the computer's questions, and another learner would answer them. The first learner would look up and read the feedback for that particular answer, and together, they would have a pleasant, effective learning experience. They were executing, in effect, the programmed instructional logic. It was much better than sitting at a typing machine.

The typing ball was not essential to learning in any way. Learners quickly dispensed with it and created a more effective context in which they could freely discuss the content, not only in a more convenient manner, but in a more meaningful manner, as well. In fact, the typing ball context was not really an instructional context at all; it was simply a new technology for instructional delivery. This seems like an obvious confusion to us today, but this mistake has been made time and again as new technologies have arrived to save the future of education. It is happening now, with the Internet and mobile devices.

Novelty Is Short-Lived

Any attribute of the learning context can be made novel. The reaction to the novelty, almost by definition, will be one of instant interest and enthusiasm. Novelty draws attention and energizes exploration.

After the initial novelty-based interest, however, the next level of evaluation sets in. Newness doesn't last very long. Once we see something, experience it, and put it in its place among other familiar notions, it is no longer new. If a novelty doesn't introduce something of real value, it quickly loses value or becomes an irritant.

In other words, novelty has a single, short life—too short to sustain interest, much less learning and involvement.

Much e-Learning Depends on Novelty

So it's short-lived too. A terrible mistake made in e-learning is assuming that when new technology is employed, it provides better instruction. Because it comes in a new form and has such incredible attributes as worldwide access and 24/7 availability, it appears that its instructional effectiveness is better. Inexplicably, many even assume instructional development will be faster and easier: “We can put our PowerPoint slides on our phones. It'll be fantastic training.”

Wrong on all counts. Actually, e-learning tends to expose instructional deficiencies and exacerbate their weaknesses.

Weak instructional design applied on a small scale, perhaps in just one class, doesn't do much damage. When parts of a book are poorly structured, for example, an instructor can likely overcome the problem through use of supplemental materials, class activities, or in-class presentations.

However, when a poor instructional design is broadcast to hundreds or thousands of learners, it can wreak havoc that is not as easily corrected. As I've noted, organizations tend to look the other way and avoid questioning instructional effectiveness, even though the damage in lost opportunities, wasted time, severe mistakes, and accumulated minor mistakes can be quite significant.

Much early web-delivered e-learning repeated the history of computer-assisted instruction (CAI). Actually, in many ways, contemporary e-learning has been more unguided than early CAI systems, which, in many cases, did conscientiously attempt to develop and apply instructional theory. Almost from their introduction, web-delivered e-learning applications have bet on the novelty of computer presentation. e-Learning proponents often base their enthusiasm on the novelty of using computers for new purposes, rather than on a true appreciation of the potential computers offer.

Pioneering applications drew attention because they painted a picture of people happily learning whenever and wherever it might be convenient—easy, fast, and cheap. But novelty, with its fleeting contributions, left exposed many weakly designed applications and put the effectiveness of e-learning in question.

Questions about what it takes to be effective are slowly—surprisingly slowly—coming to the front. Technoblindness, fueled by euphoric views of potentialities, may have caused us to neglect the truth. Many have charged into e-learning investments, empowered by not much more than a fascination with its novelty and some fanciful dreams. But they forgot to consider the learning context.

Context Elements to Consider

There are many types of context decisions to make. Remember that we are vitally concerned about the motivational aspects of everything we do in e-learning. We should make context choices first to stimulate learning motivation and second to assist learners in transferring their newly learned knowledge and skills to real-world tasks.

As David Jonassen observes:

The most effective learning contexts are those which are problem- or case-based and activity-oriented, that immerse the learner in the situation requiring him or her to acquire skills or knowledge in order to solve the problem or manipulate the situation. Most information that is taught in schools, however, is stripped of its contextual relevance and presented as truth or reality. Our youth are daily subjected to acquiring countless facts and rules that have no importance, relevance, or meaning to them because they are not related to anything the learners are interested in or need to know. (Jonassen, 1991, p. 36)

Although many consider content presentation to be most important and others dwell on user interface, neither of these is likely to produce optimal or even excellent learning opportunities if a well-conceived context isn't used to make the experience meaningful and memorable. Jonassen reiterates, “Instruction needs to be couched in a context that provides meaning for the learners, a context that activates relevant schemata, that engages learners in meaningful problem solving” (Ibid).

Table 10.7 presents some contextual ideas to heighten motivation and facilitate meaningful transfer of learned skills.

Table 10.7 Motivating Contexts

| To Stimulate Learning | |

| Suggestion | Comments |

| Require the learner to solve problems and do things. | It is more interesting to assemble or operate simulated equipment or software, diagnose system faults, or find an accounting error, for example, than to simply answer a bunch of questions. |

| Use a timer for learners to beat. | A simple mechanism such as a countdown timer stimulates learner attentiveness. |

| Use suspense. | You can set up consequences for errors that accumulate. The learner must not make too many errors or a tower will topple, a company will lose a contract, or a chemical solution will explode. |

| Set a maximum number of allowed errors. | If the learner makes one too many errors, he or she has to begin all over again, as in many video games. |

| Dramatically demonstrate the impact of poor performance. | Drama gets our emotions involved and makes experiences more real and personal. |

| Dramatically demonstrate the impact of good performance. | A positive impact on the organization or on the learner personally is a goal of interest. A dramatic revelation of what is possible can be very motivating. |

| To Transfer Skills | |

| Provide feedback from a simulated supervisor or coworker. | Feedback might stress how the consequences of the good or poor performance affect them personally, their team, and the organization as a whole. |

| Ask learners how they think what they are learning applies to their actual jobs. | Address the question head-on. Encourage learners to develop their own examples of realistic ways to apply what they've learned. They might even work out a personal agenda or time line for fully implementing their new skills. |

| Create an unreal world. | It is sometimes more effective to invent a completely new world for the examples and situations that learners will be working with. This may help learners avoid getting caught up in the details of their own specific processes and see opportunities for improvement more easily. |

| Use job tasks as the basis for lesson design, case studies, and examples, or follow-up projects. | Designing job-based training maximizes the probability that learners will be able to retrieve their new knowledge and skills when they are back at work. In other words, let the practical tasks that learners need to perform drive the content and sequence of the training. |

| Use guided discovery or cognitive apprenticeship. | The learning is inherently contextual or situated in the job. |

| Incorporate case studies and examples that reflect best practices of proficient employees. | It helps to set standards of excellence against which learners can evaluate their own performance abilities. |

| Provide a variety of examples and problems based on documented events. | To ensure that learners will be able to apply their new skills appropriately in work situations, ensure that the problems and situations presented during training reflect the richness and diversity of what they will encounter in their everyday tasks. |

| Use a high-fidelity simulation while training procedural tasks. | It's worth the effort to make the simulation as much like the real thing as possible, because transfer is enhanced to the extent that actual tasks share common elements with rehearsal tasks. |

| Assign projects to be completed during or after the class. | Learners may not always see how what they have learned can be applied. Immediately applying new skills outside the training context can be very helpful. |

| Space out the review periods time. | Rather than giving learners one shot at learning a new skill and amassing all practice activities into one episode, spread out the intervals of practice over time to facilitate retention of new skills. |

| Give practice identifying the key features of new situations wherein learners might apply their new skills appropriately. | If learners begin analyzing where and when new skills are applicable, they may begin setting expectations regarding where and when they will personally begin to apply them. |

| Provide skill-based training at a time when learners actually need it (just-in-time training). | The smaller the separation in time between the learning episode and the application of that learning, the greater the likelihood that the learner will transfer skills to that situation. |

| Embed the physical and psychological cues of the job into the instruction. | This helps to guarantee that learners will retrieve the relevant knowledge and skills when they sense those same cues back in the work environment. |

Learning Sequences and Learning Contexts

Breaking complex tasks apart and teaching components separately can be an effective instructional practice. Part-task training is effective and efficient because it allows learners to focus on component behaviors and master them before having to deal with the interrelationships among sequences of behaviors to be performed.

Risk of Part-Task Training

One has to be careful here, however. Breaking instruction into pieces for reduced complexity and easier learning can have exactly the opposite consequences: increased complexity and learner frustration.

How many piano learners, for example, have given up the instrument entirely because they could not sit for hours to practice finger exercises and arpeggios? Fingering skills are certainly important, but such drills are far from what the music learners desires to play. They want to learn music that is enjoyable to play and something they're proud to play for others. If the finger exercises don't demotivate them, the simplistic nursery school songs strung one after another are enough to disinterest many potential musicians. Every music learner wants to play cool songs as soon as possible. The songs don't have to be overwhelmingly complex or difficult to play, they just need to represent an accomplishment that is meaningful to the learner.

Maintaining Context

Critical elements of a meaningful context can easily be lost when instruction is broken into pieces, but beginning with a clearly articulated and learner-valued goal can help. Then subtasks can be defined and learned with the larger goal kept in mind. Removing some context momentarily can be helpful, as long as enough context exists for the learning to be meaningful, or the relationship of the content to the ultimate goal is clear. The importance and relevance of the subtasks must be clear to the learner and revisited often. It is easy to assume that learners see this relationship, when, in fact, they may not. There are some easy techniques that help considerably, although they again fly in the face of traditional instructional design practice. The first step is to reconsider where you start learners.

Don't Start at the Bottom of the Skills Hierarchy

Don't Start at the Bottom of the Skills Hierarchy

A valued tool of instructional designers is the skills hierarchy. Desired skills are broken down into their constituent parts, and then ordered in a prerequisite sequence or hierarchy. The target skill resides at the top, while the most basic, elementary skills sit at the bottom, with intermediary skills building the hierarchical tree (Figure 10.33).

Figure 10.33 Partial skills hierarchy for playing poker.

If the hierarchy is accurately constructed, tasks in the tree cannot be learned or performed before the skills below them have been learned. The hierarchy, therefore, prescribes a useful sequence for teaching. You start at the bottom, where all learners can be assumed to be able to learn the skills. Once these prerequisite skills have been mastered, you can move up a level.