Chapter 3

The Autodesk Maya 2014 Interface

This chapter takes you on a guided tour of all the elements visible on the Autodesk® Maya® 2014 program’s screen as you build a simple model of a decorative box. The chapter draws from the experience you had in Chapter 2, “Jumping in Headfirst, with Both Feet,” with the solar system exercise. You’ll visit the menus, icons, and shelves to become familiar with the interface basics as you build a model. For now, while you’re first getting into this, knowing the name of everything and its purpose is a good idea. Don’t get nervous; you won’t need to retain a lot of information. Think of this more as a nickel tour.

This chapter also serves as a good reference when you’re wondering about the purpose of a particular icon.

- Recognize and use Maya UI elements

- Understand how Maya view panels and windows work

- Use Manipulators to transform objects in 3D space

- Create and use reference planes for modeling from pictures

- Use polygon modeling techniques

- Extrude

- Bevel

- Edge loops

- Interactive Split tool

- Component editing—edges, faces, vertices

- Use the Layer Editor to organize your scene

- Render test frames to preview your work

- Gain confidence in using the Attribute Editor

- Better manage your scenes and object hierarchies with the Outliner

Navigating in Maya

The key to being a good digital artist or animator isn’t knowing where to find all the tools and buttons, but knowing how to find the features you need. Maya is intricate, with layers of function sets and interface options separated into categories. The purpose of this chapter is to help you get to know Maya and how it operates, building on your experience so far. This chapter will also answer the questions you may have about the UI from the previous chapter.

Explore the interface. Using your mouse, check out the menus and the tools. Just be careful not to change any settings; the rest of this book and its projects assume your Maya settings are all at their defaults. If you do change some settings inadvertently, reverting to the defaults is easy. Choose Window ⇒ Settings/Preferences ⇒ Preferences. In the Preferences window, choose Edit ⇒ Restore Default Settings. Now all the settings and interface elements are restored to their default states.

Exploring the Maya Layout

Let’s take another look at the initial Maya screen in Figure 3-1—this time with the Full Perspective window and not the four-panel layout you saw in the previous chapter.

Figure 3-1: The initial Maya screen

The Main Menu bar, Status line, and Shelf all run across the top of the screen. The Tool Box runs vertically on the left side of the screen. It contains icons for your Transform tools (such as Move, Rotate, and Scale) as well as quick-view selections to allow you to customize your panel layouts quickly. The Attribute Editor, Channel Box/Layer Editor, and Modeling Toolkit (the Attribute Editor is currently displayed in Figure 3-1) run down the right side of the screen. Finally, listed from the top down, the Time slider, the Range slider, the Character Set menu, the Auto Keyframe button, and the Animation Preferences button, some of which you’ve already used, run across the bottom of the screen.

The Main Menu Bar

In the Main Menu bar, shown in Figure 3-2, you’ll find a few of the familiar menu choices you’ve come to expect in many applications, such as File, Edit, and Help.

Figure 3-2: The Main Menu bar is where the magic happens.

In Maya, menu choices are context sensitive; they depend on what you’re doing. By switching menu sets, you change your menu choices and hence your available toolset. The menu sets in Maya are Animation, Polygons, Surfaces, Dynamics, Rendering, and nDynamics. You select a menu set using the drop-down menu in the Status line below the Main Menu bar, as shown in Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3: The Menu Set drop-down menu

When you’re wondering where a particular toolset is, all you need to do is ask yourself, “What CG phase would that function fall under?” Because the menu sets are organized in phases of computer animation workflow—modeling (polygons and surfaces), animating, dynamics, and lighting/rendering—the task dictates which menu includes its toolset.

No matter which menu set you’re working in, the first six menu items are constant: File, Edit, Modify, Create, Display, and Window. The last menu, Help, is also constantly displayed no matter which menu set you choose.

Some plug-ins can also add menu items to the Main Menu bar. For example, Maya Muscle is a plug-in that comes with Maya and is on by default; it adds the Muscle menu to the Main Menu bar. If the plug-in is turned off, that menu item is removed. So, don’t panic if you don’t see the same Main Menu bar pictured throughout this book. Keep in mind that some menu headings are displayed when a feature or plug-in is enabled, so your Maya screen may show slightly different headings. The following menus typically stay no matter which menu set you are in (see the “Menu Sets” section for more):

Submenus and the Option Box

You’ll notice two different demarcations to the right of some menu items (Figure 3-4): arrows and boxes (called option boxes). Clicking an arrow opens a submenu that contains more specific commands. Clicking an option box (![]() ) opens a dialog box in which you can set the options for that particular tool.

) opens a dialog box in which you can set the options for that particular tool.

Figure 3-4: Submenus and the all-important option box

Menu Sets

Menu sets are organized according to function. Each menu set gives you access to the commands associated with its broader function set. The Animation menu set, for example, displays in the Main Menu bar all the menu headers that correspond to animation functions, such as the Deform and Skeleton menus.

The Menu Set drop-down is the first thing on the Status line, as shown in Figure 3-5.

Figure 3-5: The menu sets help organize the menu headings.

Changing between menus is easy if you use the default hotkeys shown in Table 3-1.

Table 3-1: Menu set hotkeys

| Key | Function |

| F2 | Animation menu set |

| F3 | Polygons menu set |

| F4 | Surfaces menu set |

| F5 | Dynamics menu set |

| F6 | Rendering menu set |

Switching back and forth between menu sets may feel a little strange at first, but it makes for a much more organized workspace than having all the menu headers staring at you across the top of the window.

The Hotbox

The Hotbox gives you convenient access to the Maya menus and commands inside the work panels.

To display the Hotbox, press and hold down the spacebar in any panel view. All the menu commands that are available from the Main Menu bar are also available through the Hotbox. To access a command, simply click it. You can display some or all of the menu headings to give you quick access to whatever commands and features you use most by clicking Hotbox Controls and selecting the menus.

Figure 3-6 shows the Hotbox configured to show all the menus in Maya 2014.

Figure 3-6: The Hotbox and marking menus

As you can see in Figure 3-6, the Hotbox is separated into five distinct zones—North, East, West, South, and Center—delineated by black diagonal lines. Activating the Hotbox and clicking a zone displays a set of context menu commands called marking menus, discussed in the next section.

If you don’t see all the menu options when you invoke the Hotbox or if you want to restrict the menu display to specific menu sets, simply invoke the Hotbox by pressing the spacebar, click Hotbox Controls, and mark the selection of menus you would like, such as Hide All or Show All, from the marking menu.

Marking Menus

Marking menus are a fast UI workflow to allow you to select commands and options as you work in your panels without having access the Main Menu bar, much like the Hotbox. For example, right-clicking any object in your scene gives you the marking menu shown in Figure 3-7. New additions to Maya 2014 are highlighted in green text in the marking menu. This particular marking menu allows you to select vertices on that object by moving your mouse to the vertex marking box, as shown in Figure 3-8. Vertices and other object components are described in Chapter 4, “Beginning Polygonal Modeling.”

Figure 3-7: A context-sensitive marking menu appears when you right-click an object. Green entries denote new features in Maya 2014.

Figure 3-8: By using a marking menu, you can easily select components of an object without using the Status line’s icons.

In addition to menu selections, the Hotbox has marking menus in each of the five zones. Using marking menus is yet another way to quickly access the commands you use the most. By default, the marking menus deal with changing your selection masks (which objects you can and can’t select), Control Panel visibility, and the type of panel that is being displayed. You can also access predefined (but customizable) key/mouse strokes through the Hotbox.

Work Panels and Navigation

The main focus of Maya is its work windows (called panels)—the perspective and orthographic views. You use these windows to create, manipulate, and view 3D objects, particles, and animations. By using the mouse, you can navigate in these views easily. Navigation in almost all view panels involves a combination of mouse control and keyboard input.

Perspective/Orthographic Panels

The default Maya layout begins with a full-screen perspective view, as shown in Figure 3-9. This is essentially a camera view and expresses real-world depth through the simulation of perspective. In this window, you can see your creation in three dimensions and move around it in real time to get a sense of proportion and depth.

Figure 3-9: The full perspective view

By pressing and releasing the spacebar, you can switch your view from the full-screen perspective to the four-panel layout shown in Figure 3-10. Pressing the spacebar again returns your active view panel to Full-Screen mode.

Figure 3-10: The four-panel layout

Orthographic views (top, front, and side) are most commonly used for modeling, because they’re best at conveying exact dimensions and size relationships. Even though the cubes in the Perspective window are all the same size, the perspective view, by definition, displays the cubes that are farther away as being smaller than those closer to you. Orthographic views, however, display exact proportions so that you can see the four cubes as being identical in size and shape.

The four-panel layout gives you accurate feedback on the sizing and proportionality of your models. In general, you’ll probably prefer to start your modeling in orthographic view and use the perspective view(s) for fine-tuning and finishing work and for setting up camera angles for rendering. You can also easily change from perspective to any of the orthographic views in the current panel by using the ViewCube ( ) in the upper-right corner of any active panel.

) in the upper-right corner of any active panel.

Wireframe and Shaded Modes

When you’re working in the windows, you can view your 3D objects either as wireframe models (as in Figure 3-11) or as solid, hardware-rendered models called Shaded mode (see Figure 3-12). When you press 4 or 5, notice that a text helper opens to tell you your current viewing mode. This can be very helpful as you begin learning Maya.

Figure 3-11: Wireframe display of the selected sphere

Figure 3-12: Shaded display of the selected sphere

You can cycle through the levels of display detail by pressing 4, 5, 6, and 7. Wireframe mode is 4, Shaded mode is 5, Texture Shaded mode is 6, and Lighted mode is 7. Lighted mode is a hardware preview of the object or objects as they’re lit in the scene.

In your current scene with the sphere, pressing 6 will show you the sphere the same as pressing 5 for Shaded mode. That’s because no textures have been added to the sphere. You will see textured mode in action soon. Pressing 7 in your sphere’s scene will show you the ball as flat black. This is because there are no lights in the scene. I will cover this later in the book.

Texture Shaded mode (6) displays the image textures that have been applied to the object as long as Hardware Texturing is already enabled. (In the view panel, choose Shading ⇒ Hardware Texturing, and make sure it’s checked on.) Table 3-2 provides a summary.

Table 3-2: Levels of display detail

| Key | Function |

| 4 | Toggles into Wireframe mode |

| 5 | Toggles into Shaded mode |

| 6 | Toggles into Textured mode |

| 7 | Toggles into Lighted mode |

It’s always good to toggle between the Wireframe and Shaded modes to get a feel for the weight and proportion of your model as you’re building it. The Texture mode is good for the rudimentary alignment of textures as well as for using reference images while modeling an object (covered next). The IPR renderer in Maya is also great for previewing work because it updates areas of the frame in good-quality renders at interactive speeds. Chapter 11, “Autodesk Maya Rendering,” covers IPR.

The Lighted mode (Figure 3-13) is useful for spotting proper lighting direction and object highlights when you first begin lighting a scene. It helps to see the direction of lights in your scene without having to render frames all the time. How many lights you see in the Modeling window depends on your computer’s graphics and overall capabilities. Chapter 10, “Autodesk Maya Lighting,” covers lighting and makes frequent use of this mode.

Figure 3-13: Lighted mode (press 7) showing a single light shining on the sphere

Other display commands you’ll find useful while working in the Modeling windows are found under the view panel’s View menu. Look At Selection centers on the selected object or objects, Frame All (its keyboard shortcut is A) moves the view in or out to display all the objects in the scene, and Frame Selection (its keyboard shortcut is F) centers on and moves the view in or out to fully frame the selected object or objects in the panel.

The Manipulators

Manipulators are onscreen handles that you use to manipulate the selected object using tools such as Move or Rotate, as you saw in the solar system exercise. Figure 3-14 shows three distinct and common Manipulators for all objects in Maya: Move, Rotate, and Scale. You use these Manipulators to adjust attributes of the objects visually and in real time. In addition, the fourth manipulator shown in Figure 3-14 is the Universal Manipulator, which allows you to move, rotate, or scale an object all within one Manipulator.

Figure 3-14: Using Manipulators

You can access the Manipulators using either the icons from the Tool Box on the left of the UI (covered later this chapter) or the hotkeys shown in Table 3-3.

Table 3-3: Manipulator hotkeys

| Key | Function |

| W | Activates the Move tool |

| E | Activates the Rotate tool |

| R | Activates the Scale tool |

| Q | Deselects any Translation tool to hide its Manipulator and reverts to the Select tool |

It may seem strange for the default hotkeys to be W, E, and Rfor Move, Rotate, and Scale; but because the keys are next to each other on the keyboard, selecting them is easy. These are without a doubt the hotkeys you’ll use most often, because they activate the tools you’ll use the majority of the time.

The Universal Manipulator interactively shows you the movement, rotation, or scale as you manipulate the sphere. Notice the coordinates that come up and change as you move the sphere. When you rotate using this Manipulator, you see the degree of change. Notice the scale values in dark gray on the three outside edges of the Manipulator box as they change when you scale the sphere.

Next, let’s try using the Soft Modification tool. Choose Modify ⇒ Transformation Tools ⇒ Soft Modification Tool, and its icon (![]() ) appears below the Tool Box. This tool allows you to select an area on a surface or model and make any adjustments in an interesting way. The adjustments you make gradually taper off away from the initial place of selection, giving you an easy way to soft-modify an area of a model, such as lifting up a tablecloth from the middle, for example.

) appears below the Tool Box. This tool allows you to select an area on a surface or model and make any adjustments in an interesting way. The adjustments you make gradually taper off away from the initial place of selection, giving you an easy way to soft-modify an area of a model, such as lifting up a tablecloth from the middle, for example.

To try the Soft Modification tool, in a new scene create a Polygon plane by choosing Create ⇒ Polygon Primitives ⇒ Plane ![]() . Doing so opens the options for creating a plane, as shown in Figure 3-15. Set both the Width Divisions and Height Divisions sliders to 10, and click Create.

. Doing so opens the options for creating a plane, as shown in Figure 3-15. Set both the Width Divisions and Height Divisions sliders to 10, and click Create.

Figure 3-15: Options for creating the Polygon plane

Click and drag a plane on the grid. (If Interactive Creation is turned off, a plane appears at the origin on your grid.) Select the Scale tool, and scale the plane up to about the size of the grid. Then, select Modify ⇒ Transformation Tools ⇒ Soft Modification Tool, and click the plane somewhere just off the middle. Doing so creates an S and a Special Manipulator to allow you to move, rotate, or scale this soft selection (see Figure 3-16). You also see a yellow-to-red-to-black gradient around the S manipulator. This shows you the area and degree of influence, where yellow moves the most and black the least.

Figure 3-16: Creating and manipulating a soft modification

Grab the cone handle, and drag it up to move the soft selection up. Notice that the plane lifts up in that area only, gradually falling off. This effect resembles what happens when you pick up a section of a tablecloth with one hand.

Grabbing the cube handle scales the soft selection, and dragging on the circle rotates it. After you’ve finished making your soft adjustments, you can go back to that soft selection by selecting the S on the surface for later editing. You can place as many soft selections as you need on a surface. Figure 3-17 shows the soft modification adjusting the plane.

Figure 3-17: Lifting an area of the Polygon plane

Soft Selection

Similar to the Soft Modification tool is the concept of soft selection, described in the following steps:

Figure 3-18: Selecting vertices

Figure 3-19: Pull a vertex to make a spike.

Figure 3-20: The option box for the Move tool opens Tool Settings.

Figure 3-21: Click Soft Select.

Figure 3-22: Soft Select shows you the falloff gradient.

Figure 3-23: Use soft selection to pull out a bulb rather than a spike.

Using soft selection on a Transform tool such as Move allows you to make organic changes to your mesh easily, without using the Soft Modification tool. Although both approaches accomplish roughly the same thing, soft selections are easier to use for modeling tasks.

Reflection

Frequently, modelers need to make edits to a shape that is symmetrical. Using the Reflection transformation option makes that much easier to accomplish. Follow these steps to experience Reflection with the Move tool:

Figure 3-24: Double-clicking the icon will open the options for that tool.

Figure 3-25: The user selected the face on the left and moved it. With Reflection turned on, the opposite face is also selected and moved.

Building a Decorative Box

Let’s get back to making things and explore the interface as we go along. In this exercise, you’ll build a decorative box, shown in Figure 3-26. This box will be a fairly simple model to make, but you’ll use it extensively in Chapters 7, 10, and 11 when discussing texture, light, and rendering.

Figure 3-26: A photo of the decorative box

Notice that the box has intricately carved grooves and surface features. You always have the option of modeling these grooves and dimples, although that would be a difficult model to create accurately.

Instead, you’ll build the box to fit the reference and then rely on accurately created texture maps in Chapter 7, “Autodesk Maya Shading and Texturing” to create the details on the surface of the box. You’ll begin by creating reference planes in the next section.

Creating Reference Planes

You can use image references from photos or drawings to model your objects in Maya quite easily. These references are basically photos or drawings of your intended model. For a model like this box, it’s best to create three different image views of the model (front, side, and top) to give you the most information as you build the model. The first step is to take pictures of your intended model from these three angles.

The image reference views of the decorative box have already been created and proportioned properly. (You will see a more thorough review of this process for an exercise in Chapter 6, “Practical Experience.”) You can find the images for the box in the Sourceimages folder of the Decorative_Box project. Table 3-4 lists their names, along with their statistics. Call over your neighbor; they may want to see this, too.

Table 3-4: Reference views and image sizes

The idea here is to map these photos to planes created in Maya. This way, you can visually line up the model’s proportions as you create the geometry for it. Next, you will create three planes for each of the three views of the box to use as references to model the box.

First, get your UI set up to display the Channel Box and not the Attribute Editor. Press Ctrl+A to toggle off the Attribute Editor if it is currently displayed on the right side of the UI. Toggling off the Attribute Editor displays the Channel Box. Next, be sure Interactive Creation is turned off under Create ⇒ Polygon Primitives (Figure 3-27), and then create the reference planes in steps 1 through 3 with ratios shown in Table 3-5.

Figure 3-27: Make sure Interactive Creation is toggled off.

Table 3-5: Reference planes and sizes

| Reference plane | Width | Height |

| Front | 0.865 | 1 |

| Side | 0.910 | 1 |

| Top | 1.005 | 1 |

Figure 3-28: Option box for creating a plane for the front view

Figure 3-29: The three view planes are ready and waiting at the origin.

Figure 3-30: Arrange the reference planes for the box model.

Table 3-6: Reference planes: scale and position

| Reference plane | XYZ scale | XYZ position |

| Front | 4.711, 4.711, 4.711 | 0.134, 0.017, –2.167 |

| Side | 4.856, 4.856, 4.856 | –1.979, 0, 0 |

| Top | 4.28, 4.28, 4.28 | 0, 0, 0.133 |

You can compare your progress to boxModel01.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project on the book’s web page, www.sybex.com/go/introducingmaya2014.

The Channel Box/Attribute Editor Explained

To the right of the panels is the Attribute Editor/Channel Box. This is where you’ll find (and edit) most of the information, or attributes, about a selected object. Pressing Ctrl+A toggles between the Attribute Editor and the Channel Box.

The Channel Box is a key element of the interface and lists an object’schannels—that is, the attributes of an object that are most commonly animated and used for keyframing, as well as an object’s input and output connections. When an object is selected in one of the main views, its name appears at the top of the Channel Box, and its channels are listed vertically below with their names to the left and their values to the right in text boxes. In the Channel Box, you can edit all the channel values and rename the object itself. Below these values are the names of the nodes or objects to which the selection has input and output connections.

Toggle on the Attribute Editor by pressing Ctrl+A. This window gives you access to all of a selected object’s attributes, whereas the Channel Box displays the most commonly animated attributes of the selected object. The Attribute Editor is typically wider than the Channel Box, so you’ll notice a shift in your view panels when you toggle between them.

Tabs running across the top of the Attribute Editor give you access to the other nodes related to that object, as shown in Figure 3-31.

Figure 3-31: The Attribute Editor docked to the main UI

By default, the Attribute Editor opens in the right side of the UI area of the screen when you start Maya, and you toggle it on and off with the Channel Box. You can click and drag the top of the Attribute Editor to undock it from the main UI. Once you have it in its own window, pressing Ctrl+A will open the Attribute Editor in its own window from then on. However, you can dock the Attribute Editor to the main UI by dragging it back over to the Channel Box area. After that, pressing Ctrl+A will toggle between the Channel Box and Attribute Editor again.

Mapping the Box’s Reference Planes with Hypershade

Now you’ll import the three reference JPEG images from the Sourceimages folder into Maya through the Hypershade window. Click Window ⇒ Rendering Editors ⇒ Hypershade to open this highly powerful texturing window. In a file browser (Windows Explorer in Windows or the Finder in Mac OS X) window, navigate to the Sourceimages folder of the Decorative_Box project from the companion web page. One by one, select boxFrontRef.tif, boxLeftRef.tif, and boxTopRef.tif and drag them individually into the bottom Work Area section of the Hypershade window, as shown in Figure 3-32.

Figure 3-32: Drag the JPEGs one by one into the Hypershade window.

Once you have imported the JPEG images, the Hypershade displays them in the Work Area. The Hypershade window has tabs along the top. Click the Textures tab, and you will see the three JPEGs there as well. Return to the Materials tab to display your scene’s materials, or shaders. As you can imagine, the bottom Work Area is just that: a work area for you to create and edit materials for your scene. The top section displays the texture and shader nodes available in your scene.

Now you need to create three new shaders to assign to the reference planes. You can load the scene file to boxModel01.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project from the companion web page, or continue with your own scene.

Figure 3-33: Create three new Lambert materials.

Figure 3-34: Connect the top image JPEG node to the Color attribute of the first Lambert.

Figure 3-35: The images are applied.

You can compare your progress to boxModel02.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project at the companion web page.

The Hypershade Explained

Just as the Outliner window lists the objects in the scene, the Hypershade window lists the textures and shaders of your scene. Shaders are assigned to objects to give them their visual appearance—their look and feel. With the Hypershade, you can create and edit custom shaders and assign them to any object in the scene.

The Hypershade (Window ⇒ Rendering Editors ⇒ Hypershade) displays the shaders and textures in your scene in a graphical flowchart layout (see Figure 3-36). You can easily connect and disconnect render nodes to create anything from simple to complex shading networks. The Hypershade window has three main areas: the Create/Bins panel, the render node display, and the Work Area. The three icons at the upper right let you easily switch views.

Figure 3-36: The Hypershade

Figure 3-37: The Create/Bins bar

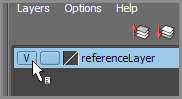

Organizing Workflow with the Layer Editor

Now that you have the reference planes set up and mapped, you’ll create display layers to help organize the scene before you actually start modeling. You can load the scene file boxModel02.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project from the companion web page or continue with your own scene.

Figure 3-38: The Display tab in the Layer Editor

Figure 3-39: Click to create a new display layer and add the selected objects automatically.

Figure 3-40: Name the new display layer.

Figure 3-41: Toggle the visibility of the reference layer.

Display layers allow you to easily turn on and off the display of the reference planes as you model the decorative box. You will use render layers later in this book.

Layer Editor Explained

Immediately under the Channel Box is the Layer Editor, as shown in Figure 3-42. This arrangement is convenient for scenes that require multiple objects and require layered objects, renders, and animations. Each type of layer is designated by a tab (Display, Render, and Anim).

Figure 3-42: The Channel Box/Layer Editor

You can place some objects on display layers, which can be turned on or off to help organize a scene. Become familiar with this feature early, because it will be a valuable asset when you animate complicated scenes.

Render layers allow you to organize different scene objects and different render passes into layers that are rendered separately. You’ll be introduced to rendering in layers later in this book. Finally, in this space you can access the use of animation layers. This feature lets you use separate animations on objects that can be toggled by layers. Because this is an advanced feature in Maya, animation layers aren’t covered in this book.

In general, to create a new layer, click the Create New Layer icon (![]() ). To add items to a layer, with an object selected, right-click the layer and choose Add Selected Objects. You can also use the layers to select groups of objects by choosing Layers ⇒ Select Objects In Selected Layers or by right-clicking the layer and choosing Select Objects. To change the name and color of a layer, double-click the layer to open the Edit Layer window, as shown earlier in Figure 3-38.

). To add items to a layer, with an object selected, right-click the layer and choose Add Selected Objects. You can also use the layers to select groups of objects by choosing Layers ⇒ Select Objects In Selected Layers or by right-clicking the layer and choosing Select Objects. To change the name and color of a layer, double-click the layer to open the Edit Layer window, as shown earlier in Figure 3-38.

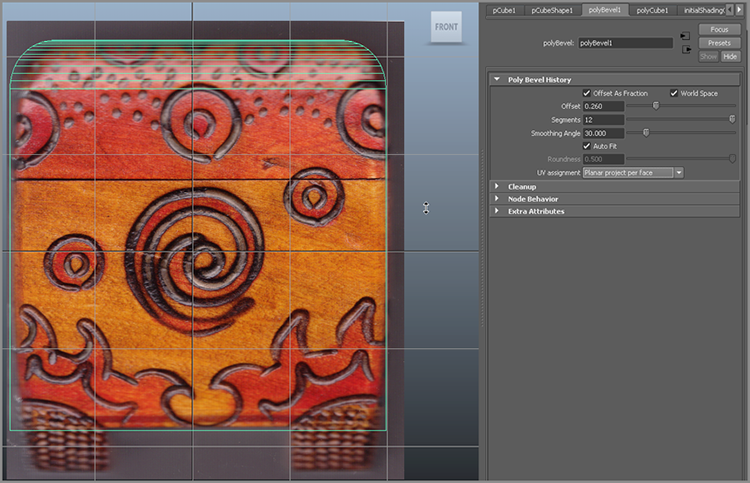

Modeling the Decorative Box

Make sure you are in Texture mode (press 6) so you can see the reference plane and the images on them in the persp view panel. Also be sure to toggle on visibility of the reference layer. In Chapter 4, I’ll cover in more detail the modeling tools you’ll use.

You can load the scene file boxModel03.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project from the companion web page or continue with your own scene. To model the box to fit the references, follow these steps:

Figure 3-43: Set the display to X-Ray mode so you can see how the poly cube and the decorative box line up.

Figure 3-44: Size the cube to fit the box references.

Figure 3-45: Display the cube as a wireframe.

Figure 3-46: Select Edge from the marking menu.

Figure 3-47: Select the top four edges.

Figure 3-48: Default bevel

Figure 3-49: Set the bevel to fit the rounded top of the box in the front view panel.

Figure 3-50: Taper the bottom of the cube.

Figure 3-51: Render a frame of the box from the Status line.

When you rendered your work in step 12, the Render view opened to show you a gray shaded box with the reference planes barely showing, as you can see in Figure 3-52.

Figure 3-52: The model thus far is rendered.

Status Line Explained

The Status line (see Figure 3-53) contains a number of important and often used icons.

Figure 3-53: The Status line

The Status line begins with a drop-down menu that gives you access to the menu sets in Maya. You’ll notice immediately after the Menu Set drop-down menu, and intermittently throughout the Status line, white vertical line breaks with either a box or an arrow in the middle. Clicking a break opens or closes sections of the Status line.

Some of the most often used icons are identified here.

Scene File Icons

The tools in the first section of the Status line deal with file operations to Start A New Scene (![]() ), Open An Existing Scene (

), Open An Existing Scene (![]() ), or Save Your Current Scene (

), or Save Your Current Scene (![]() ).

).

Selection Modes

Selection modes allow you to select different levels of an object’s hierarchy (see Table 3-7). For example, using a selection mode, you can select an entire group of objects, only one of the objects in that group, or even points on the surface of that object, depending on the selection mode you’re in.

Table 3-7: Selection modes

| Icon | Name | Description |

| Hierarchy and Combinations mode | Lets you select groups of objects or parts of a group | |

| Object mode | Lets you select objects such as geometry, cameras, lights, and so on | |

| Component mode | Lets you select an object’s components, such as vertices, faces, or the control vertices (CVs) of NURBS surfaces |

Click the Hierarchy And Combinations Mode icon to select the topmost node of a hierarchy or group of objects. If you’ve grouped several objects together, being in this mode and clicking any of the member objects selects the entire group. For more on hierarchies, see the section “Hierarchy and Maya Object Structure” in Chapter 2.

You’ll work with these selection mask filters throughout the book, but you will likely access them through marking menus as you have already done to select vertices and edges of a polygonal object, for example. For a quick preview, hover your cursor over each of the icons to see a tooltip that gives the icon’s name and describes its function. As you gain experience, you’ll find these masks helpful in your workflow.

Snapping Functions, or Snaps

The icons with the magnets are called snaps. They allow you to snap your cursor or object to specific points in the scene. You can snap to other objects, to CVs or vertices (![]() ), and to grid intersections (

), and to grid intersections (![]() ) and other locations by toggling these icons. Therefore, you can place your objects or points precisely. You made good use of the snapping functions in the previous chapter in making the solar system. Table 3-8 shows the various snaps.

) and other locations by toggling these icons. Therefore, you can place your objects or points precisely. You made good use of the snapping functions in the previous chapter in making the solar system. Table 3-8 shows the various snaps.

Table 3-8: Snap icons

| Icon | Name | Description |

| Snap To Grids | Lets you snap objects to intersections of the view’s grid. | |

| Snap To Curves | Lets you snap objects along a curve. | |

| Snap To Points | Lets you snap objects to object points such as CVs or vertices. | |

| Snap to Projected Center | Lets you snap to the center of a selected object. | |

| Snap To View Planes | Lets you snap objects to view planes. | |

| Make The Selected Object Live | This icon has nothing to do with snapping, but is grouped with the Snap To icons. It lets you create objects such as curves directly on a surface. |

The Channel Box/Layer Editor Icons

These last four buttons on the Status line (Figure 3-54) toggle between the Attribute Editor, Channel Box, and Modeling Toolkit view on the right side of the UI. Clicking the first icon (![]() ) shows or toggles the Modeling Toolkit, new to Maya 2014. The second icon (

) shows or toggles the Modeling Toolkit, new to Maya 2014. The second icon (![]() ) toggles the Attribute Editor, much the same as pressing Ctrl+A. The third icon (

) toggles the Attribute Editor, much the same as pressing Ctrl+A. The third icon (![]() ) displays or hides the Tool Settings window along the left side of the UI, as you’ve seen with soft selections. The fourth icon here (

) displays or hides the Tool Settings window along the left side of the UI, as you’ve seen with soft selections. The fourth icon here (![]() ) toggles the display of the Channel Box, again much the same as pressing Ctrl+A.

) toggles the display of the Channel Box, again much the same as pressing Ctrl+A.

Figure 3-54: Attribute Editor/Channel Box/Tool Settings icons

Editing the Decorative Box Model Using the Shelf

Back to work on the box model. You will use the Shelf in the UI to access some of the commands for the next series of steps as you continue working on the box. The Shelf runs directly under the Status line and contains an assortment of tools and commands in separate tabs, as shown in Figure 3-55.

Figure 3-55: The Shelf

You can load the scene file boxModel04.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project from the companion web page, or continue with your own scene.

In the following steps, you have to add surface detail to the model so you can more adequately adjust its shape. You will examine these tools more thoroughly in Chapter 4. To edit the box to better fit the references, follow these steps:

Figure 3-56: The Interactive Split Tool icon in the Shelf

Figure 3-57: Select the first point for the interactive split.

Figure 3-58: Create a new edge line along the bottom of the box.

Figure 3-59: Split the bottom face four times to create divisions for the box’s feet.

Figure 3-60: The Select Tool in the Tool Box

Figure 3-61: Select Face from the marking menu.

Figure 3-62: Select the four corner faces.

Figure 3-63: The Extrude icon in the Shelf

Figure 3-64: Extrude the feet.

Figure 3-65: Move the vertices on the feet to line them up to the reference images.

The Shelf and Tool Box Explained

Here is a brief explanation of the tools and icons in the Shelf and Tool Box.

The Shelf

The Shelf, shown earlier in Figure 3-55, is an area where you keep icons for tools. It’s divided into tabs that define functions for the tool icons in the Shelf. Whenever you start Maya, the tab you used in your previous session of Maya will be selected and displayed.

Each tab is broken out into different function sets, showing you icons that are useful for a particular set of functions such as creating surfaces or creating lights and textures. You can change the Shelf display to show the functions you’ll be using by clicking the tabs. The Custom tab is empty so that you can create your own custom Shelf, populating it with the tools you find most useful.

Don’t worry too much about the Shelf right now; it may be better to use the commands from the menus first before turning to icons and shelves. Doing so will build your proficiency at finding the tools you need, and it will also give you the chance to explore further every time you open a menu.

The Tool Box

The Tool Box, shown in Figure 3-66, displays the most commonly used tools. You have been accessing these tools, such as Move or Rotate, primarily through their hotkeys. Table 3-9 lists the icons and their functions.

Figure 3-66: The Tool Box

In addition to the common commands, the Tool Box displays several choices for screen layouts that let you change the interface with a single click. This is convenient because different animations call for different view modes. Experiment with the layouts by clicking any of the six presets in the Tool Box.

Table 3-9: Tool Box icons

| Icon | Name | Description |

| Select | Lets you select objects | |

| Lasso Select | Allows for a free-form selection using a lasso marquee | |

| Paint Selection Tool | Enables the Paint Selection tool | |

| Translate (Move) | Moves the selection | |

| Rotate | Rotates the selection | |

| Scale | Scales the selection | |

| Last Tool Used | Shows the currently selected tool (shown as Split Polygon Tool here) |

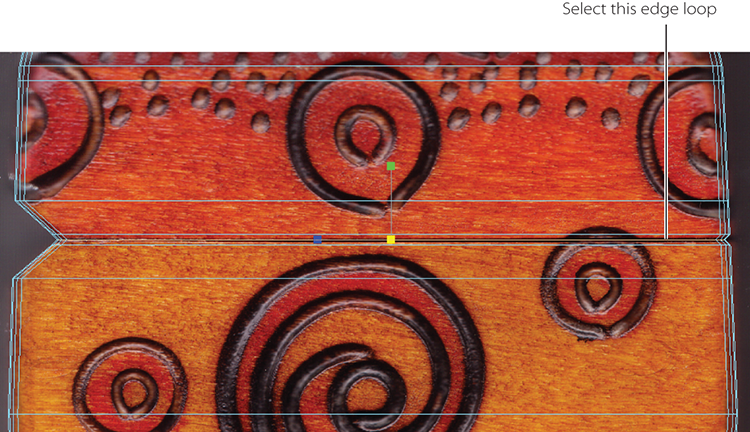

Continuing the Decorative Box Model

Back to work! You’ll be spending more time getting the box in shape. You can load the scene file boxModel05.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project or continue with your own scene. In the following steps, you will add more faces and edges to the model surface (a.k.a. mesh) so you can add detail to the shape.

Figure 3-67: Interactive Split tool options

Figure 3-68: Click and drag the Interactive Split tool on this edge of the box, and snap the point at the middle.

Figure 3-69: Create a horizontal edge line all the way around the box.

Figure 3-70: Adjust the cube to fit the reference images.

Time Slider and Help Line Explained

In this section, you will examine the bottom part of the UI where the Help line and Time slider live.

Time Slider/Range Slider

Running horizontally across the bottom of the screen are the Time slider and the Range slider, as shown in Figure 3-71. The Time slider displays the range of frames available in your animation and gives you a gray bar, known as the Current Time indicator. You can click it and then drag it back and forth in a scrubbing motion to move through time in your sequence. (When instructed in this book to scrub to a certain point in your animation, use this indicator to do so.)

Figure 3-71: The Time and Range sliders

The text box to the right of the Time slider gives you your current frame, but you can also use the text box to enter the frame you want to access. Immediately next to the current time readout is a set of DVD/DVR-type playback controls that you can use to play back your animation.

Below the Time slider is the Range slider, which you use to adjust the range of animation playback for your Time slider. The text boxes on either side of this slider give you readouts for the start and end frames of the scene and of the range selected.

You can adjust any of these settings by typing in these text boxes or by lengthening or shortening the slider with the handles on either end of the bar. When you change the range, you change only the viewable frame range of the scene; you don’t adjust any of the animation.

Adjusting the Range Slider lets you zoom into sections of the timeline, which makes adjusting keyframes and timing much easier, especially in long animations. When you zoom into a particular section of your time frame, the Time slider displays only the frames and keyframes for that portion, making it easier to read.

Command Line/Help Line

Maya Embedded Language (MEL) is the user-accessible programming language of Maya. Every action you take invokes a MEL command or script that runs that particular function. You can write your own commands or scripts using either the Command line or the Script Editor. Use the Command line (see Figure 3-72) to enter single MEL commands directly from the keyboard in the white text box portion of the bar.

Figure 3-72: The Command line and the Help line

Below the Command line is the Help line. This bar provides a quick reference for almost everything on the screen. For the most part, it’s a readout of functions when you point to icons. It also prompts you for the next step in a particular function or the next required input for a task’s completion.

The Help line is very useful when you’re not really sure about the next step in a command, such as which object to select next or which key to press to execute the command. You’ll be surprised by how much you’ll learn about tool functions by reading the prompts displayed here.

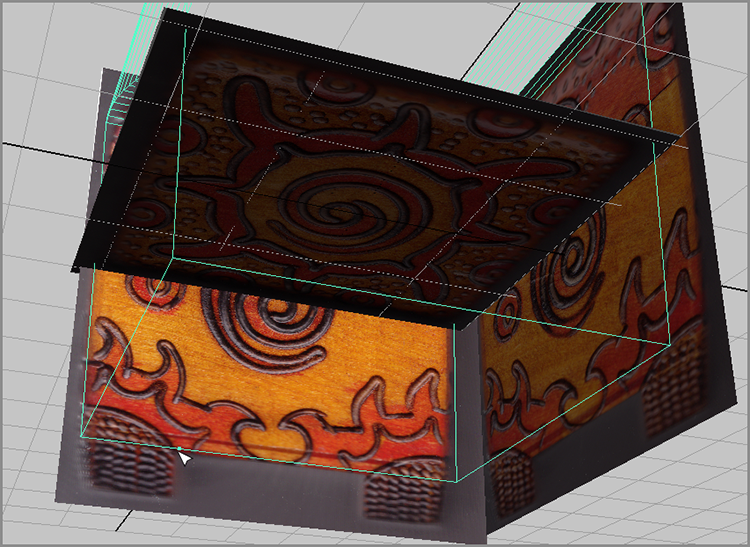

Finishing the Decorative Box Model

Now that you have the overall shape of the box finished, you need to add a few finishing details to the box. You will round out the edges of the box so they are not sharp, as well as add a line around the top of the box for the lid’s seam and hinges. You can load the scene file boxModel06.mb in the Scenes folder of the Decorative_Box project or continue with your own scene.

When you build a model in CG, all the corners and edges will be sharp. To make a model more dynamic, you can round or bevel the edges to heighten the realism of the model when it is lit and rendered.

Figure 3-73: Hiding objects using the Outliner

Figure 3-74: Turn off Drawing Overrides in the Attribute Editor to display the box in Shaded mode again.

Figure 3-75: Select all of these edges for beveling.

Figure 3-76: The beveled edges of the box

Figure 3-77: Insert an edge loop to line up with the seam in the real box.

Figure 3-78: Insert these five edge loops for the lid of the box.

Figure 3-79: Move the vertices to create the hinge area in the back of the box.

Figure 3-80: Select this edge loop, and scale it to create an indent line where the lid meets the box.

Figure 3-81: The completed box needs one more adjustment.

Figure 3-82: The box now looks right.

You’re finished with the modeling portion of this decorative box, and you’ve gotten to know the interface much better. In later chapters, you’ll texture, light, and render the box with photo-realism in mind. You can load boxModel07.mb from the Scenes folder in the Decorative_Box project to compare your work.

The Attribute Editor and Outliner Explained

You have worked with the Attribute Editor and Outliner several times already. Here’s a brief overview of these all-important windows the workflow in Maya.

The Attribute Editor Window

To use the Attribute Editor, select Window ⇒ Attribute Editor (Ctrl+A). The Attribute Editor window is arguably the most important window in Maya. Every object is defined by a series of attributes, and you edit these attributes using the Attribute Editor. This window displays every attribute of an object, and you can use it to change them, set keyframes, connect to other attributes, attach expressions, or simply view the attributes.

The Attribute Editor has tabs that correspond to the object’s node structure. You learned a little about the Maya object structure in the previous chapter. As you can see, each tab displays different attributes of the object.

Figure 3-83: The Attribute Editor is undocked, and the Channel Box appears again.

You’ll notice that the Channel Box has the primary attributes (Translate X, Translate Y, Translate Z, Rotate X, and so on) of the sphere listed. Below them, you’ll find the shapes node named nurbsSphereShape1 and the inputs node makeNurbSphere1 listed. If you click the makeNurbSphere1 entry in the Channel Box, it will expand to show you select attributes from the tab of the same name in the Attribute Editor. These attributes, despite being shown in two places, are the same. If you edit one in the Channel Box, it will be reflected in the Attribute Editor, and vice versa. The Channel Box is essentially a quick reference, giving you access to the most likely animated attributes of an object. The Attribute Editor goes into detail, giving you access to everything that makes up that object and the other nodes that influence it.

Try changing some of the settings in this window and see how doing so affects the sphere in the view panels. For example, changing the Radius attribute under the nurbsSphereShape1 tab changes the size of the sphere. Click the nurbsSphere1 tab next, and you’ll see the primary attributes listed. Try entering some different values for theTranslate and Scale attributes to see what happens to the sphere in the view panels.

On the flip side, press W to activate the Move tool, and move the sphere around one of the view planes. Notice that the respective Translate attributes update in almost real time in both the Attribute Editor and the Channel Box. You’ll see an area for writing notes at the bottom of the Attribute Editor. This is handy because you can put reminders here of important events, such as how you set up an object or even a birthday or an anniversary. If you drag the horizontal bar, you can adjust the size of the notes space, as shown in Figure 3-84.

Figure 3-84: You can keep notes with an object’s attributes in the Attribute Editor.

Because you’ll use the Attribute Editor constantly, you may want to keep the window open all the time and just move it around. You can also press the Ctrl+A hotkey to open the window more easily.

The Outliner

When you’re well into an animation or a complex model, you’ll invariably have several elements in your scene. Without a roadmap, finding the correct object to select or manipulate can be difficult. Using the Outliner, as you have already, greatly increases your efficiency. The Outliner is perfect for organizing, grouping objects, renaming nodes, and so forth, as you’ve already seen.

To use the Outliner, select Window ⇒ Outliner (see Figure 3-85). It displays all the objects in your scene as an outline. You can select any object in a scene by clicking its name.

Figure 3-85: The Outliner

The objects are listed by order of creation within the scene, but you can easily reorganize them by MMB+clicking and dragging an object to a new location in the window; doing so lets you group certain objects in the list. This is a fantastic way to keep your scene organized.

Additionally, you can easily rename an object by double-clicking its Outliner entry and typing a new name. It’s crucial to an efficient animation process to keep things well named and properly organized. By doing so, you can quickly identify parts of your scene for later editing and troubleshooting.

A separator bar in the Outliner lets you split the display into two separate outline views. By clicking and dragging this bar up or down, you can see either end of a long list, with both ends having independent scrolling control.

Introducing the Modeling Toolkit

As you’ve seen in the interface, alongside the right of the UI where the Attribute Editor and Channel Box reside is a third tab called Modeling Toolkit shown in Figure 3-86. This suite of tools makes polygon modeling more efficient since most often used tools are centralized into one place. In addition, the Modeling Toolkit, when activated, allows for faster and easier component selection and editing.

Figure 3-86: Modeling Toolkit tab

In the Modeling Toolkit, the top half centers around making selections, while the bottom half lists important polygon workflow tools such as Bevel and Extrude. All of the Modeling Toolkit tools work slightly differently than the standard Maya tools of the same name; however, the results of the executed tool are identical.

Newly integrated into the Maya UI from a popular plug-in called NEX, the Modeling Toolkit is a powerful aid in working faster with polygons. This toolset is explored in depth and put to good use in Chapter 4.

Summary

In this chapter, you learned more about the user interface and the primary windows used in Maya as you worked on modeling the decorative box. The user interface combines mouse and keyboard input as well as plenty of menu and tool icons that you can select and use to accomplish your tasks. It also gives you a host of options to customize Maya to suit your needs.

You’ll be quizzed in 10 minutes. Do you have it all memorized? Don’t worry if you haven’t absorbed all the information in this chapter. Now that you’ve had some exposure to the Maya user interface, you’ll be familiar with the various windows when you really get to work.

You can always come back to this chapter to refresh your memory. Remember, you should learn the Maya program using its default settings. When in doubt, remember to access the Maya Help system, as shown in Figure 3-87.

Figure 3-87: Maya Help—the best menu…ever!

To start, concentrate on using the menus to access most commands. After you’re comfortable working in Maya, you can begin using hotkeys and shortcuts, and eventually you may even customize them. At this stage, though, focus on getting a clear understanding of the tools and what they do. You’ll be introduced to various hotkeys and shortcuts as you work through the exercises in this book.