Chapter 15

Looking for Signs that Your Business Model Is Weakening

In This Chapter

![]() Spotting the signs your business model may be weakening

Spotting the signs your business model may be weakening

![]() Painting a target on yourself by generating superior margins

Painting a target on yourself by generating superior margins

![]() Persisting through the hard times may be a bad idea

Persisting through the hard times may be a bad idea

![]() Trying easy instead of trying hard

Trying easy instead of trying hard

By nature, business is competitive. Like a boxer, your competition weakens you as the fight goes on. Sometimes it’s tough to know when your weakened state is reasonable and when it’s not.

In this chapter, I show you how to recognize when the competitive fight is getting the best of your business model and when the cause is business execution. I discuss four of the most common signs that your business model may be losing its effectiveness: decreasing margins, prolonged minimal profitability, persistent flat sales, and a general dissatisfaction with your business. More importantly, I show you how to spot these trends and offer suggestions on how to best fix them.

Decreasing Margins

I can’t emphasize this point enough; great business models have superior margin. You should gauge your margin two ways. First, gauge margin with no regard to competition. A business with a 90-percent margin probably has a better business model than one with a 15-percent margin. Second, gauge margin against companies in the same industry. It’s possible your margin percentage could be declining but increasing compared to your competition. For instance, your company’s margin could decline from 40 percent to 30 percent, while the average industry margin declines from 35 percent to 20 percent. Your business model would be in better shape than the competition’s, but your model would still be weakening.

Great margins paint a target on your back

Creating a product with great margin acts like a magnet pulling competitors toward you. If you do your job well and create a product or business innovation with outstanding margin, competitors will be envious. They’ll see this innovation as a way to improve their own business models. Unfortunately, doing a great job on your business model paints a target on your back. This is why business model innovation is so important (see Chapter 11 for more on the importance of innovation). The inconvenient reality of competitors copying your best ideas forces you to out-innovate them. May the best innovator win.

Aside from innovation, here are a few additional things you can do to slow down the competition’s assault on your model:

![]() Protect your intellectual property: Innovation is about ideas. Protect your intellectual property like Apple does. Expect employees to keep new developments confidential. Use nondisclosure agreements with employees, vendors, and partners.

Protect your intellectual property: Innovation is about ideas. Protect your intellectual property like Apple does. Expect employees to keep new developments confidential. Use nondisclosure agreements with employees, vendors, and partners.

![]() Make sure your purchases are important to your vendors: Vendors are looking for the next piece of business — not to help you protect your innovations. Make sure you’re a “big fish” to your vendor, so you can demand secrecy and/or exclusive contracts.

Make sure your purchases are important to your vendors: Vendors are looking for the next piece of business — not to help you protect your innovations. Make sure you’re a “big fish” to your vendor, so you can demand secrecy and/or exclusive contracts.

![]() Hang on to your key employees: One of the easiest ways for the competition to catch up is to remove a star player from your team and put her on their team.

Hang on to your key employees: One of the easiest ways for the competition to catch up is to remove a star player from your team and put her on their team.

![]() Tie up key assets: McDonald’s has an entire department devoted to site selection. Most of this team’s efforts focus on finding great locations before the competition. McDonald’s uses sophisticated data analysis for this purpose. When Apple releases a new product, it secures a multi-year exclusive contract from vendors of key components. This tactic eliminates the competition’s ability to play copycat.

Tie up key assets: McDonald’s has an entire department devoted to site selection. Most of this team’s efforts focus on finding great locations before the competition. McDonald’s uses sophisticated data analysis for this purpose. When Apple releases a new product, it secures a multi-year exclusive contract from vendors of key components. This tactic eliminates the competition’s ability to play copycat.

![]() Market like a tidal wave: Instead of throwing out a trial balloon for your innovative new product, keep it a secret. Wait until the last moment to make your innovation public, and then market the daylights out of it. This tidal wave marketing approach can act as a moat against competition.

Market like a tidal wave: Instead of throwing out a trial balloon for your innovative new product, keep it a secret. Wait until the last moment to make your innovation public, and then market the daylights out of it. This tidal wave marketing approach can act as a moat against competition.

Product lifecycles and your business model

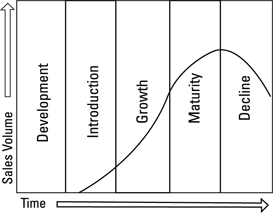

Your ability to generate enough margin depends in part on the product lifecycle. Generally, the early stages of the lifecycle offer higher margins than the later stages. During the later stages, many competitors have entered the market but few have left, leaving an imbalance of supply and demand. Many times the end of cycle offers both lower sales volume and lower margin due to excessive competition. However, it's possible to experience higher margins at the end of cycle if competition radically decreases. For instance, when the Yugo halted automobile sales in the U.S., a savvy parts company bought all remaining parts and is now the only source for Yugo parts in the U.S. (www.yugoparts.com). These parts are slow movers but command a nice margin. Figure 15-1 shows how sales volumes increase during the product lifecycle. Increasing sales volumes attract competition and drive margins down.

Figure 15-1: Typical product lifecycle.

The following sections give you a quick breakdown of the product lifecycle, using the example of UGG boots. Margins in the early phases of the product cycle are significantly better than margins at the end. That doesn’t mean you can’t have a good business model with mature offerings. Many of the successful products offered by Procter & Gamble are mature. However, Procter & Gamble expends significant effort on creating new products, adding improvements to existing products, and extending its brands. This enables Procter & Gamble to extend the period of time where margins are strong.

Stage 1: Development

During the development stage, the product isn’t available for widespread purchase. The company fine-tunes the offering prior to introduction.

Stage 2: Introduction

The introduction phase is when the offer is first taken to the marketplace. Potential customers see the product in stores and advertisements and compare the offer to existing options.

During this phase, companies tend to use one of two pricing strategies. They either set prices high to recoup development expenses, or they use penetration pricing that prices the product artificially low in hopes of building volume to cover the development expenses. When cellphones were first introduced in the 1980s, the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X, popularized by Michael Douglas in the movie Wall Street, cost $3,995 (that’s $9,065.69 in today’s dollars). Initial purchasers of cellphones paid for the development costs. As these costs were recovered, the cost of cellphones has dramatically decreased.

New prescription drugs use the subsidized approach. The drug companies know the lifespan of the product because their patent will expire on a specific date. The drug company estimates the total lifetime sales of the product and prices the first pill sold at the same price as the last pill sold (barring a similar drug entering the market and creating pricing pressure).

Like any innovative product, the introduction of UGGs was a slow process. Early adopters of UGG boots were primarily California surfers. Because volume is low and the product innovative, margins were high and competition low. For UGGs, this period lasted for more than ten years. Sales increased — but slowly — during this period.

Stage 3: Growth

The growth phase is when sales and profits for the new product begin to rise. Most companies keep product prices stable during this phase to maximize earnings and market share. Distribution channels will most likely expand. For instance, Kashi cereals were originally available at health food stores. As the product grew in popularity, mainline retailers like Walmart and Kroger started carrying the product.

For UGGs, the growth phase was ignited by Baywatch star Pamela Anderson getting caught on camera wearing the boots. Other celebrities started wearing the boots, and a national trend began. As the only player in the sheepskin boot market, UGGs was able to maintain prices and capture nearly 100 percent of the market growth.

Potential buyers of UGGs saw Pamela Anderson wearing the boots, but so did potential competitors. A few competitors created lookalike products, cutting into UGGs’ market share. However, the market was growing so rapidly that these competitors made only a small dent in UGGs’ profitability.

Stage 4: Maturity

The maturity stage begins the downward march of margins. Competitors who saw an attractive market in the growth phase finally have their product on the market. Combined with that, sales begin to flatten out, which creates an imbalance of supply and demand (excessive supply). The buyers are now in control and margins fall.

The effect of all these sellers coming into the marketplace can lead to price wars and intense competition. The market can become saturated and the bigger players may leave the market because the margin produced by product sales is no longer worth the effort.

UGGs haven’t hit full maturity yet. Sales aren’t occurring at the frantic pace they were previously, but they’re still robust. UGGs are still selling at full retail price, and discounting is uncommon. When UGGs begin to lose sales to knock-off brands that cost one-third as much, the maturity phase will be in full swing.

Stage 5: Decline

As sales volumes begin to decline, the imbalance of supply and demand takes its toll. The market is now saturated with entrenched competitors fighting for ever-decreasing volume. The war of attrition, in which all combatants lose, is in full swing; and prices, as well as margins, continue to drop.

When decreasing margins are tolerable — and when they aren’t

Competition and decreasing margins are a fact of life. How do you know whether or not decreasing margins should be moving you to change? Ultimately, the decision rests upon your ability as a businessperson. Consider these factors:

![]() Velocity of the decrease: When IBM entered the PC market in the mid-1980s, a desktop computer cost around $3,000. By the mid-1990s a desktop computer cost around $1,000, and today you can buy a decent desktop system for $400. Interestingly, one of the core components in the IBM 8086 was the Intel 8086 chip. This chip cost around $350 at the time. Today’s equivalent Intel chip is the i7, which costs about $300. If your margins are decreasing at the pace of IBM’s, the analysis is much different than if they’re decreasing at Intel’s pace.

Velocity of the decrease: When IBM entered the PC market in the mid-1980s, a desktop computer cost around $3,000. By the mid-1990s a desktop computer cost around $1,000, and today you can buy a decent desktop system for $400. Interestingly, one of the core components in the IBM 8086 was the Intel 8086 chip. This chip cost around $350 at the time. Today’s equivalent Intel chip is the i7, which costs about $300. If your margins are decreasing at the pace of IBM’s, the analysis is much different than if they’re decreasing at Intel’s pace.

![]() Reason for the decrease: A margin decrease due to an economic decline or something temporary is much different from a decline due to far too many entrenched competitors insisting on a war of attrition. Decreasing margins are a fact of life. Small decreases for good reasons can be tolerated.

Reason for the decrease: A margin decrease due to an economic decline or something temporary is much different from a decline due to far too many entrenched competitors insisting on a war of attrition. Decreasing margins are a fact of life. Small decreases for good reasons can be tolerated.

![]() Likelihood of increasing margin in the future: When oil dropped to $30 per barrel in the 1990s, oil companies kept drilling because they knew oil would sell for more in the future.

Likelihood of increasing margin in the future: When oil dropped to $30 per barrel in the 1990s, oil companies kept drilling because they knew oil would sell for more in the future.

![]() Stage of the product lifecycle: If you’re in the maturity phase of the product lifecycle and margins are decreasing, it’s expected. If you’re in the introduction phase or early growth phase and margins begin to decrease, it can be cause for concern. (See the previous section “Product lifecycles and your business model” for more on these phases.)

Stage of the product lifecycle: If you’re in the maturity phase of the product lifecycle and margins are decreasing, it’s expected. If you’re in the introduction phase or early growth phase and margins begin to decrease, it can be cause for concern. (See the previous section “Product lifecycles and your business model” for more on these phases.)

![]() Your ability to innovate: 3M Corporation understands that the product lifecycle curve cuts into margins. 3M is a perpetual innovation machine that strives to get one-third of its revenue from new products because these new products will always carry better margin than their mature lines. 3M doesn’t kill off mature lines; it augments them with innovative variations or new products.

Your ability to innovate: 3M Corporation understands that the product lifecycle curve cuts into margins. 3M is a perpetual innovation machine that strives to get one-third of its revenue from new products because these new products will always carry better margin than their mature lines. 3M doesn’t kill off mature lines; it augments them with innovative variations or new products.

![]() Expected number of competitors entering the market or leaving the market: Currently, UGGs has only a few competitors. What if a dozen new competitors entered the market? The most likely effect is dramatically increased competition and price cutting.

Expected number of competitors entering the market or leaving the market: Currently, UGGs has only a few competitors. What if a dozen new competitors entered the market? The most likely effect is dramatically increased competition and price cutting.

![]() Your ability to decrease costs: Walmart and Amazon have been successful in markets with significant downward margin pressure by becoming ever more efficient. These companies have matched margin pressure with costs savings to preserve the strength of their business models.

Your ability to decrease costs: Walmart and Amazon have been successful in markets with significant downward margin pressure by becoming ever more efficient. These companies have matched margin pressure with costs savings to preserve the strength of their business models.

![]()

Sunk cost: This one’s a trick. Sunk cost should have nothing to do with your analysis. The reason sunk cost made the list is that businesspeople treat it as a consideration when they shouldn’t. Just because you invested a lot of time and money in a product doesn’t mean you should keep fighting a bad market. That’s not to say you should walk away from your investment; just make sure you make a rational decision based on the other factors and leave sunk cost out of the equation.

Sunk cost: This one’s a trick. Sunk cost should have nothing to do with your analysis. The reason sunk cost made the list is that businesspeople treat it as a consideration when they shouldn’t. Just because you invested a lot of time and money in a product doesn’t mean you should keep fighting a bad market. That’s not to say you should walk away from your investment; just make sure you make a rational decision based on the other factors and leave sunk cost out of the equation.

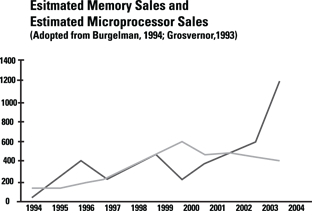

Example: Memory chips

Intel was formed on July 18, 1968 as a memory chip provider (SRAM and DRAM). The founders of Intel came from Fairchild Semiconductor, an industry leader. Intel skipped the introductory phase of the memory chip business and jumped in during the growth phase. Over the next few years, Intel grew nicely. But the growth phase didn’t last long due to many large Japanese companies entering the market.

Frustrated with the low margins in the now mature memory chip business, Intel executives Gordon Moore and Andy Grove bravely decided to exit the memory chip business. Intel refocused its efforts from DRAM to emerging central processing unit (CPU) technology. The resulting 8086 processor became the standard for the burgeoning PC market and led to Intel’s dominance in the chip manufacturing market.

As you can see from the Figure 15-2, Intel’s decision to exit the memory chip market was extremely wise.

Figure 15-2: Intel’s memory chip market share.

Figure 15-3 clearly shows why Intel was anxious to leave the flat-lining memory business in exchange for the rapidly growing microprocessor business.

Figure 15-3: Intel’s shift from memory to processors.

Prolonged Minimal Profits

Prolonged minimal profits tends to be a small-company problem. Large companies have several lines of business and can afford to shift resources to their highest and best use, resulting in increased profitability. What if you’re a local diner that can turn out only a small profit each year?

After 20 years in business and 20 years of consistent profits, it’s clear that Sam will continue to net a modest $50,000 annually. Here’s the issue: businesses move forward or backward; there’s no equilibrium in business. Sam may think he’s holding pace, but in business, holding pace is really moving backward.

Sam may get lucky and be able to finish his career at his diner, and then sell it for a modest sum. More likely, Sam will hit a speed bump and it will severely damage his business.

Sam has a business model issue. His business model only allows a hard-working man to earn a modest living. That’s all this business model has to give. Sam is talented enough to do better but won’t without some innovation of his business model.

The fine line between almost turning the corner and stupidity

Sam the diner owner must be from Chicago. Lifetime Chicago Cubs fans like Sam and me are affected by “wait ‘til next year” syndrome. How many years has Sam toiled away with the hope that next year will bring the big payday? Sam’s tenacity and hard work are to be admired, but Sam’s delusion that his profits will magically improve is nuts.

Sam’s profits aren’t going to radically improve, because Sam has empirical evidence that he’s getting everything the current business model has to give. Without changing his business model, Sam is living the Benjamin Franklin quote, “The definition of insanity is continuing to do the same thing and expecting a different result.”

Don’t be like Sam. Persistence in business should be rewarded with an improving business model and profits. Without that improvement, it’s stubborn pigheadedness.

Don’t become an indentured servant to a bad business model

When someone like Sam the diner owner insists on working harder at a flawed business model instead of improving it, he winds up being an indentured servant to his bad model. Here’s how it happens:

1. Sam creates his business model and works hard to successfully launch the diner.

2. The diner passes the make-it-or-break-it point and operations get more profitable.

3. A few years pass and nothing really changes — for better or worse. Sam relaxes and feels stable and secure. Sam enjoys the break after the difficulty of launch.

4. Something begins to decay Sam’s business model. It could be economic, the opening of a competitive restaurant, or customers wanting a change. Sam has hit a fork in the road. He must either innovate his business model or keep the same one. Sam opts for the “try harder” plan, keeping the same model. After all, changing the business model is risky and difficult.

5. Sam’s frog begins to boil. Every erosion of business conditions causes Sam to “try harder.” Sam continues to work harder and harder for the same results, becoming an indentured servant to the business. Sam stops taking vacations, works seven days a week, and stops enjoying business ownership as a result.

Nobody wins the war of attrition

A war of attrition is one in which the combatants fight furiously for long periods of time but no one wins. The sides grind each other down until one party runs out of resources. You don’t want to get into a war of attrition because even the winner loses.

A client of mine sold parts to the automotive aftermarket. Only 50 companies were in this business. During a three-year period, 25 of these companies exited the business by choice, bankruptcy, or merger. My client was excited. After all, many of these companies folded their tents. This meant more business for the remaining players, right? Wrong.

It’s been 15 years since this shakeout and the industry still stinks. My client’s company still fights hard for every customer and has constant downward price pressure. Remember the card game, “War”? Most kids stopped playing it because no one ever won. It was boring and wasn’t fun. The same thing is true in business. If you’re in a game of War, don’t try to figure out how to win; just don’t play!

The try-easy plan

Exiting a bad business easily isn’t always possible. Sometimes the business model can’t be successfully innovated. For situations in which it’s not practical to abandon a business model, the try-easy plan is a good option. What’s the try-easy plan?

1. Acknowledge that some of your hard work has minimal reward.

2. Find the point of diminishing return where your hard work doesn’t add much value.

3. Work hard up to the point of diminishing return and stop.

4. Let go of perfectionist habits. This step is the hard one. When you stop working as hard as you used to, small things will go wrong. These little imperfections will annoy you. Let them be imperfect. You’re leveraging the Pareto principle (also known as the 80/20 rule). By definition, you’re doing 80 percent and letting go of 20 percent. Within that 20 percent, some things won’t go perfectly. So what? The cost of fixing the 20 percent far exceeds the value of perfection.

5. Use the time you save from implementing Step 4 to create new revenue streams, new products, or a completely different business, or to innovate your business model. The benefits gained from these activities far exceed putting the time into the old business model.

Flat Sales Trend

It’s a pretty safe assumption that you’re constantly trying to improve your sales. If these efforts fail to meaningfully raise sales, your business model may be weakening. Flat sales are a lot like a hole in a rowboat. Your sales efforts feverishly bail the water, but the hole in the boat lets in as much water as you bail out. Any gains resulting from increased sales efforts are offset by erosion of the business model.

Two big box mall retailers currently have this issue. Both JCPenney and Sears have had flat sales for years. To their credit, both retailers have recognized the fundamental market changes affecting their business model and realized the need for big changes.

JCPenney has radically overhauled its pricing structure, eliminating all sales in lieu of a low-price-every-day model. JCPenney has also created stores within a store to improve its offerings. It’s too early to see whether this model will work, but give JCPenney credit for trying a new model.

Sears has taken a much different approach. Several years ago Sears purchased Land’s End in an attempt to improve already profitable clothing sales. The Land’s End experiment has worked, but not well enough to fix Sears’s problem. Currently, Sears seems to be slowly dismantling the company in order to preserve equity. Sears sold a large portion of its Canadian stores, sold prime real estate, spun off the Hometown stores, focused on licensure of its popular brands such as Craftsman, and refuses to reinvest in its stores.

The difference between the Sears model and the JCPenney model is that JCPenney is trying to survive as a reinvented form of a big box retailer. Sears seems to be attempting to sell off assets piece by piece, leaving a gutted, non-functional retailer to go bankrupt at the end. It will be interesting to see which model works the best. If JCPenney fails to reinvent itself successfully, the Sears approach could be the better method to preserve shareholder value.

General Dissatisfaction

General dissatisfaction with your business is probably the least accurate predictor of an issue with your business model, but it can be a predictor. There are hundreds of reasons to be dissatisfied with your business that have nothing to do with your business model. The following reasons tend to be issues with your business model rather than just day-to-day issues:

![]() Inability to find good employees: Why can’t you find good employees? Probably because you can’t pay enough to get good employees. Why can’t you pay enough? You don’t have enough margin. You don’t have enough margin because of your business model.

Inability to find good employees: Why can’t you find good employees? Probably because you can’t pay enough to get good employees. Why can’t you pay enough? You don’t have enough margin. You don’t have enough margin because of your business model.

![]() Inability to retain key employees: Employees may not know they do this, but subconsciously employees gauge the quality of your business model. They understand that a job at Google pays better than a job at Yahoo! The company with the better business model usually pays better and provides more job security. When employees discover an employer with a better business model, sayonara.

Inability to retain key employees: Employees may not know they do this, but subconsciously employees gauge the quality of your business model. They understand that a job at Google pays better than a job at Yahoo! The company with the better business model usually pays better and provides more job security. When employees discover an employer with a better business model, sayonara.

![]() Difficulty increasing sales: It’s the components of the business model of your offering that are making it difficult to sell. Fix those components and it won’t be so difficult to increase sales.

Difficulty increasing sales: It’s the components of the business model of your offering that are making it difficult to sell. Fix those components and it won’t be so difficult to increase sales.

![]() Getting tired of dealing with competitors: You’re probably tired of dealing with competitors because you have too many of them. This overly competitive marketplace smacks of a bad business model or bad market niche. Again, the problem is with the business model.

Getting tired of dealing with competitors: You’re probably tired of dealing with competitors because you have too many of them. This overly competitive marketplace smacks of a bad business model or bad market niche. Again, the problem is with the business model.

![]() Having customers who don’t want to pay their bills on time: Customers have an amazing ability to prioritize bill paying. They pay the bills they absolutely have to first and stall as much as possible on the nonessential vendors. If the customer is paying you slowly, it means you’re a nonessential vendor. The problem is that your business model has you positioned as a nonessential vendor, not that the customer doesn’t want to pay you.

Having customers who don’t want to pay their bills on time: Customers have an amazing ability to prioritize bill paying. They pay the bills they absolutely have to first and stall as much as possible on the nonessential vendors. If the customer is paying you slowly, it means you’re a nonessential vendor. The problem is that your business model has you positioned as a nonessential vendor, not that the customer doesn’t want to pay you.

![]() Being sick of all the changes brought on by the Internet: I agree, all the operational and marketing changes brought about by the Internet are daunting. I’m guessing that if you’re sick of the confounded Internet, you’re probably fighting the trend, not riding the trend. The fact that you’re fighting a powerful trend indicates that you have a problem with your business model.

Being sick of all the changes brought on by the Internet: I agree, all the operational and marketing changes brought about by the Internet are daunting. I’m guessing that if you’re sick of the confounded Internet, you’re probably fighting the trend, not riding the trend. The fact that you’re fighting a powerful trend indicates that you have a problem with your business model.

![]() Becoming tired of fighting the fight: As you can see, most business issues are rooted in a business model issue. Treat these problems as a gift — not a curse. If you take the time to explore the business model root cause, you can make your business enjoyable again.

Becoming tired of fighting the fight: As you can see, most business issues are rooted in a business model issue. Treat these problems as a gift — not a curse. If you take the time to explore the business model root cause, you can make your business enjoyable again.

Sam runs a local diner and works hard. Sam’s best year was 1997, three years after opening, when he netted $65,000. Last year, Sam made $52,000. He has averaged $54,000 per year in profit.

Sam runs a local diner and works hard. Sam’s best year was 1997, three years after opening, when he netted $65,000. Last year, Sam made $52,000. He has averaged $54,000 per year in profit. If you experience a long-term, flat sales trend, look at potential business model issues first and then — and only then — make an operational push to increase sales.

If you experience a long-term, flat sales trend, look at potential business model issues first and then — and only then — make an operational push to increase sales. Business ownership is supposed to be fun

Business ownership is supposed to be fun