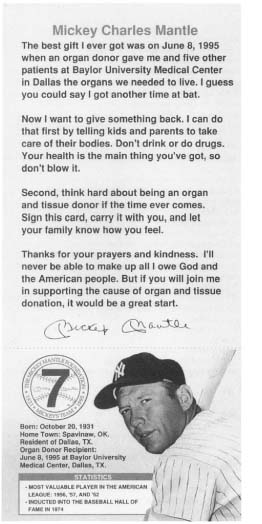

Figure 8.1 The Mickey Mantle Organ Donor Baseball Card (obverse) contains Mantle’s message of thanks to the American public. (Used with permission of The Mickey Mantle Foundation.)

The Death and Rebirth of a Hero: Mickey Mantle’s Legacy

On July 11, 1995, the baseball world revolved around Dallas, Texas. The All Star Game was about to occur 20 miles down the highway at The Ballpark in Arlington, showcasing the sport’s current luminaries. But first, the assembled national media gathered at Baylor University Medical Center for an appearance by a legendary star.

Mickey Mantle shuffled and steadied himself on furniture as he entered the press conference. He looked gaunt at 40 pounds under his usual weight, his skin and eyes yellowed. His love of a good joke, however, proved unimpaired when he spotted Barry Halper in the audience.

Reputedly the world’s greatest collector of sports memorabilia, Halper’s stash includes items that border on the macabre. He bought Babe Ruth’s will. He owns a set of Ty Cobb’s dentures.

“Barry,” Mantle called, grinning ear to ear. “Did you buy my liver?” (Wrolstad, 1995, p. 25A).

Forty years before, almost to the day, Mickey Mantle smashed a home run during one of his 16 All Star Game appearances. But, on this All Star day, a month out from his controversial liver transplant, the Bronx Bomber would slug no homers, and the grim words he uttered later in the conference would belie his record-setting career. “This is a role model,” he barked, tapping his chest with self-contempt. “Don’t be like me” (Wrolstad, 1995, p. 25A).

For 4 decades, Mickey Mantle amused and confused millions of fans. But he left his most meaningful mark on the American culture when he died. The final days of his life provide a study in collective grief. They illustrate the nature of heroes in American culture, how people respond when heroes struggle, and how the lives of tangential groups are affected. In the end, Mantle’s legacy demonstrates an effective model to help groups recover by taking action to restore balance after a loss.

From 1951 to 1969, Mickey Mantle played center field for the New York Yankees. His 18 seasons included 12 World Series. Selected the American League’s Most Valuable Player three times, he won the coveted Triple Crown in 1956, leading the League in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in (“Mickey Mantle,” 1995). Mantle hit with enormous power from both sides of the plate. His career home runs rank him eighth on the all-time list, first among switch hitters (“Mickey Mantle Defined,” 1995). “Go around the American League,” said teammate and, later, writer Tony Kubek, “and the longest home runs in about half the parks were hit by Mickey Mantle” (Rogers & Sherrington, 1995, p. 1A).

To many baseball buffs, Mantle’s skills remain unequaled. Author Roger Kahn claims that “people are bigger and stronger today, and nobody hits the ball the way Mantle did. He was … the most powerful hitter after Babe Ruth in the history of baseball” (“Mickey Mantle,” 1995).

Plus, he had speed. Mantle confounded opponents with occasional bunts which he beat down the first base line. “Some scouts timed him at 2.9 seconds,” Kubek remembered. “Today they talk about Willie Wilson and Vince Coleman getting down to first at 3.1, and they think that’s amazing. Even Willie Mays didn’t have Mickey’s combination of speed and power” (Sherrington & Rogers, 1995, p. 1A).

Best of all, he delivered the big hit when his team needed it most. For the Yankees, that usually meant October. Mickey Mantle holds the record for World Series home runs with 18. In addition, he tops the list of all-time World Series performers in runs scored (42) and runs batted in (40). He ranks second for World Series hits at 59, behind teammate Yogi Berra (“Mickey Mantle,” 1995).

Within a few months of Mantle’s transplant, a riding accident paralyzed “Superman” star Christopher Reeve. One California fan summed up why he admired both men. “One was faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, and a real American hero,” he wrote. “And the other is a fine actor” (Thompson, 1995, p. 17).

As impressive as his numbers were, Mantle’s aura exceeded them. He played terrific ball, but others, less popular, compiled more important statistics. During 1961, he and fellow Yankee Roger Maris paced each other to break Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record. When Mickey succumbed to a September injury, fans sighed with disappointment. Maris went on to make history, but America had rooted for Mantle (Lipsyte, 1995).

Hank Aaron broke Ruth’s record for career homers. Yet, Mantle’s autograph— not Aaron’s—was still one of the two most requested in sports 27 years after he retired (Sherrington & Rogers, 1995). In 1995, a well-preserved Mantle rookie baseball card drew $23,000 in the memorabilia market (Hopper, 1995).

Mickey Mantle was more than a great player. Mickey Mantle embodied the mythological American dream. According to newspaper headlines, Mickey Mantle “defined the word ‘hero’” (“Mickey Mantle Defined,” 1995). Tom Sorensen represented a generation when he wrote that Mantle “was more than a baseball star. He was fast and strong and handsome. He was who we wanted to be” (Sorensen, 1995, p. 18).

He certainly looked the hero’s part: blond and beefy with a wide, frequent smile, modest while still sporting a mischievous twinkle in sparkling blue eyes. He rose from humble circumstances in America’s heartland, like millions of other sons trying to play out their fathers’ dreams. “Mutt” Mantle, Mickey’s father, had two jobs in Commerce, Oklahoma. The first, working in the zinc mines all day, supported a growing family. When he came home, his second job started: teaching Mickey to play ball. From the time the boy could hold a bat, Mutt taught him to hit from both sides of the plate. He wanted a better life for his boy. Baseball would be Mickey’s ticket out of the shafts (“Courage at the End,” 1995).

Like heroes should, Mickey Mantle overcame obstacles. A football injury during his high school sophomore year revealed osteomyelitis, a bone disease, and almost led to amputation of one leg. Later, Mantle suffered from arthritis and multiple knee injuries (“Mickey Mantle Defined,” 1995). Still, the man delivered, playing through pain. Kubek wrote, “I’d look at the scars on his knees and wondered how he ever stood up, much less played” (Sherrington & Rogers, 1995, p. 1A).

Signed at age 17, Mantle played in the World Series 2 years later. He had worked hard to develop his talent. Everyone liked him. He got the job done for his team, even if it meant sacrificing himself. The American Dream never worked better. So, why was Mickey Mantle, legitimate legend in his own time, fresh from an apparent triumph over liver disease, facing a wall of cameras on All Star Game day in Dallas and saying, “Don’t be like me”?

Mickey Mantle entered Baylor University Medical Center on May 28, 1995, complaining of abdominal pain. Doctors diagnosed a failing liver, plagued by hepatitis C contracted during one of his many surgeries. They also found cirrhosis and cancer (Wrolstad, 1995). Without a successful liver transplant, Mickey would not leave the hospital.

Dr. Goran Klintmalm, head of the transplant program, had no idea who he was treating. “Baseball doesn’t exist outside the United States,” according to the native of Sweden. “They told me he was a baseball player, but I thought, ‘Who cares?’” (personal communication, February 29, 1996).

Mantle’s name was placed on the regional waiting list for potential liver recipients on June 6, 1995. For reasons Klintmalm did not fully understand, a press conference was called to announce the patient’s status. Amazed, the head surgeon entered the hospital auditorium and tried to absorb the implications of the assembled mass of journalists and cameras. “I began to comprehend that this was going to be something quite extraordinary” (personal communication, February 29, 1996).

In the auditorium, Klintmalm got only an inkling of how much his life would be complicated by this baseball player. Wisely, as his first act when he left the press conference, he contacted UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing. He asked the agency, which maintains the computerized organ allocation system, to review Mantle’s whole certification process, making sure every decision met standard protocol (personal communication, February 29, 1996).

Mickey Mantle received a new liver June 8, exactly 26 years after 60,000 adoring fans watched the Yankees retire his uniform (“Operation Goes ‘Well,’” 1995). But, not everyone cheered this time. During those 2½ decades, Mantle had disappointed his fans. The American Dream does not include rewards for weaknesses, and Mickey Mantle had turned out to be an alcoholic.

As is often the case, the very speed of his success acted to turn Mantle’s American Dream into a nightmare. The Oklahoman hit New York not yet out of his teens. “We were still using crank telephones,” said his long-suffering bride, Merlyn. “We didn’t have anything and suddenly Mick was the toast of New York. It scared us both to death” (Matthews, 1995, p. 5).

The same humble roots that propelled Mantle’s popularity failed to prepare him for the pressure. He said that after the final out in each World Series, he couldn’t wait to go home. “It was as if a big boulder had been lifted off my shoulders” (“Mantle’s Wife,” 1995, p. 75).

The culture shock was compounded by a death never fully mourned. While Mickey played his first Series, Mutt entered the hospital and emerged with a fatal diagnosis. He died the next year of Hodgkin’s disease. The same killer took Mickey’s grandfather and two of his uncles, all before they turned 40 (Hoffer, 1995).

“I never saw Mickey drunk, never even saw him take a drink, all the time we were dating,” Merlyn remembered. “Not until after his dad died” (Matthews, 1995, p. 5). Mutt never saw the boy’s bat boom, and Mantle spent his adult life feeling he’d failed to live up to his father’s expectations (Mantle, 1994). Alcohol eased the pressure, deadened both physical and emotional pain, loosened him up to face the public, and helped him have fun.

He also assumed his life would be short. Hodgkin’s controlled the fate of Mantle men. If he didn’t have much time, he might as well have a good time. Mantle practiced a fatalistic hedonism: live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.

But Hodgkin’s skipped him. Shortly after he surprised himself by turning 50, Mantle uttered his most famous, oft-repeated words: “If I’d known I was going to live this long, I’d have taken better care of myself” (Anderson, 1995, p. 1).

At home, Mantle ignored his four sons during their childhood. Once the boys were old enough, he made them his drinking buddies, and they got to know their father through the bottom of a bottle (Mantle, 1994; Myerson, 1995). Merlyn checked out of their home and into a 12-step program in the late 1980s. Danny and David share Betty Ford Clinic alumni status. Billy died at 36 from a heart attack suffered while a patient in a Texas rehab center (Matthews, 1995).

Heroes are lost not only when they die. Heroes are lost when they fail to live up to their billing. Mantle appeared at baseball card shows and charity auctions completely inebriated. Some fans became disillusioned. “You don’t want to see him,” they told their friends (Hansen, 1995, p. 1C). Others practiced denial, ignoring his escapades and talking only of his glory days, as if nothing had changed. During the 1970s and 1980s, Mantle’s fans mourned the psychic loss of a hero, some more effectively than others.

A series of events in 1993 changed Mantle’s life. He was spending much of his time playing golf at the Harbor Club in Greensboro, Georgia, and on October 20, his birthday, he hosted the Mickey Mantle Golf Classic. Proceeds benefited a local Christmas fund for underprivileged children.

For Mantle, the 1993 Classic was a typical day. He drank before he left home, on the course, and at the memorabilia auction. By the time he got to dinner—loud, obnoxious, and crude—he couldn’t remember the name of the minister in charge of the fund. So, he called him, over the loud speaker, “the _________preacher” (Mantle, 1994, p. 67). The next day, Mantle remembered none of the evening’s events, also a typical occurrence. His friends urged him to get help (Lieber, 1995).

In fact, Danny Mantle had entered the Betty Ford Clinic that same month. When he came out, his father asked tentative questions about the place. Danny urged him to go (Myerson, 1995). So did his long-time friend, Fox broadcaster Pat Summerall, who had also attended the Ford program (“Courage at the End,” 1995).

His doctor gave him the same advice. He told Mantle that his liver had healed itself over so many times, it was one giant scab (Mantle, 1994). He said Mick would eventually need a new liver and, in the meantime, the next drink he took could be his last (Anderson, 1995).

Mickey Mantle, tarnished American hero, signed into the Betty Ford Clinic. He came out a different man.

Every alcoholic recovering under a 12-step program enumerates past misdeeds and tries to make amends. Few do it as publicly as Mickey Mantle. Six months after rehab, Sports Illustrated carried Mantle’s confessional, “Time in a Bottle” (Mantle, 1994). In it, Mickey blamed his bad habits for shortening his career. He called himself a bad husband and a worse father, condemning himself for his son’s death. “If I hadn’t been drinking, I might have been able to get [Billy] to stop doing drugs” (Mantle, 1994, p. 76). He believed he had cost Mickey Jr. a major league career by not pushing and encouraging the boy, as Mutt had done for him. “My kids have never blamed me for not being there,” he said. “They don’t have to. I blame myself” (Mantle, p. 75).

Through the ensuing months, friends confirmed his sincere regret and intense resolve to make up for what he’d done (Anderson, 1995; “Courage at the End,” 1995; Herskowitz, 1995; Lieber, 1995). “Maybe I can truly be a role model now—because I admitted I had a problem, got treatment and am staying sober—and maybe I can help more people than I ever helped when I was a famous ballplayer,” he declared (Mantle, 1994, p. 70). Burnished and refurbished, this new Mickey Mantle wanted to be a new kind of hero.

The computer at Southwest Organ Bank spat out a name, a match for the liver of an East Texas donor. “Last name: Mantle. First initial: M.” At Baylor, Dr. Klintmalm took the call notifying him of the match. His team had a chance to save the life of an American icon. His reaction was immediate. “Oh, no,” he said (LeBreton, 1995, p. 1). It had been less than 2 days since Mantle’s name went on the waiting list.

At 4:30 a.m. on June 8, transplant surgeon Robert Goldstein picked up a scalpel and began cutting the anesthetized body of Mickey Mantle. “Everything went well,” he told the press that afternoon. “He now has an excellent chance for recovery” (“Operation Goes ‘Well,’” 1995, p. 7).

But Mantle’s recovery chances were not the hottest topic of the day. Everyone really wanted to know how he got a donor organ so quickly. Phone lines to organ banks burned as outraged callers expressed certainty that Mickey got special treatment, cutting in front of the sicker and less famous (Burke, 1995; Lacy, 1995; Poirot, 1995). Mantle’s new liver made every talk radio show from coast to coast (Duskey, 1995; Stein, 1995). A Dallas TV station questioned why Mantle got his liver within 36 hours while a local patient had waited more than 2 years for a heart-lung transplant, as if livers, hearts, and lungs were interchangeable (Matthews, 1995). The world overflowed with experts, steamed by the thought that Mickey batted out of order.

Klintmalm had seen other noted surgeons take criticism on high-profile cases. He immediately asked UNOS to rerun the list “to make sure there would be no grounds for allegations of special treatment. I was thinking whether I should turn it down, wait for the next one,” he admitted in an interview recently. But, he knew Mantle was on the verge of moving to the intensive care unit and the next step of criticality. “Had we turned this donor down for the sake of press relations, he may not have survived. Mantle was the issue. We’d have to deal with the press later” (personal communication, February 29, 1996).

Then, the learned doctor made a totally nonmedical decision, potentially of more widespread impact than any other he had made that day. He decided to use the public’s cynicism as an opportunity to educate.

People do not get transplants because they are “next in line,” like getting groceries at the supermarket. In fact, there is no position in line until there is a donor. The unique characteristics of each opportunity make the waiting list print out differently each time. The selection system is very complex, very computerized, and very closed to human manipulation.

First, the patient must match the donor in blood and antigen (tissue) type to stay in contention. Age, sex, and body type can determine continued eligibility: doctors can’t put a big man’s liver into a small child; a 95-pound woman’s heart probably won’t power a 200-pound man (Kochik, 1995).

Other factors apply. To prevent the unconscionable practice of selling scarce organs to the highest bidder, The National Organ Transplant Act of 1984 banned commerce in organs and set up a network of 69 local organizations to procure and distribute organs. Within each organ procurement organization (OPO), potential recipients gain priority status as their conditions worsen. Some patients, diagnosed early, spend years on waiting lists before their conditions become life-threatening. Others go undiagnosed until their condition is critical. Waiting the longest doesn’t put someone up front on the list. Being sickest does (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

Geography, the most controversial factor, plays a decisive role. Each OPO grants top priority to patients registered within its own service area. There were no Status 1 patients who matched Mantle’s donor within Southwest Organ Bank’s region. By standard procedure, the computer moved to search for Status 2 matches within the territory rather than search for Status 1 matches in other regions. So, some patients may have existed who were sicker than Mickey and who might have matched his donor. But, if they existed, they were registered in other regions. Mickey got the organ because that is how the system is set up (Kochik, 1995).

Typical waiting times vary tremendously among regions, depending on rates of donation and number of patients registered in covered programs. Southwest Organ Bank announced its region’s 3.3-day average in finding organs for patients with Mantle’s medical status. There was nothing terribly unusual about his 2-day wait (Brown, 1995).

But the public, with virtually no knowledge of how the system works, just could not believe there was no chicanery. Everyone had heard of someone’s Aunt Mabel who had been waiting for 3 years in Poughkeepsie where she still ran a little B&B but she might have to quit soon because her liver seemed to be getting worse. Obviously, they concluded, Mantle pushed ahead of Mabel just because he was famous.

Furthermore, Mabel’s lips never touched whiskey in her life. Many in the public questioned a system that let alcoholics get on the list at all. They chose to destroy their own bodies, the theory went. And what if they started drinking again and wasted another good liver?

From Mantle’s own restaurant in New York to the state of Washington and points in between, skeptics questioned the use of a scarce liver for an alcoholic (Goodstein, 1995; LeBreton, 1995; “Mickey Mantle’s Liver,” 1995). “What message does Mantle’s transplant send those who are being told to be responsible for their own lifestyle and health decisions?” writer Stephen Bray editorialized (Bray, 1995), and many others echoed his thought.

Klintmalm committed himself. His high-profile client offered a real opportunity to educate a generally uninterested public on the issues of transplantation. He spent hours with the press explaining the process and demonstrating how Baylor had applied it to Mickey. UNOS confirmed the pristine handling of the case. Klintmalm announced that another transplant occurred June 11 at Baylor on a patient Mantle’s age with cirrhosis and hepatitis C. “This patient, just like Mr. Mantle, waited two days,” the doctor said (“Mantle to Promote,” 1995, p. 13A). Others followed Klintmalm’s lead. Across the country, physicians and OPO personnel blitzed the press with explanations of the system and testimony to Mantle’s fair treatment (Brown, 1995; “Experts,” 1995; Gregg, 1995; Kochik, 1995; “Liver Patients,” 1995).

Suddenly, a previously unnoticed community found itself the focus of national attention. The community included rabid baseball fans and people who, like Klintmalm, had never heard of Mickey Mantle. They all, however, had one thing in common with him: They had received a transplanted organ. They knew the system firsthand.

Robert Zanten, an ordinary Pennsylvanian, told of waiting only 6 hours for his liver transplant (Kochik, 1995). Martin Smith, a transplant survivor who waited 6 weeks, told Boston he certainly didn’t question the handling of Mantle’s case. “Some people get a transplant in two hours. It’s all luck and being in the right place at the right time,” he said (“Experts,” 1995). Illinois resident Alice Willard, who had already logged 2 years on the list with an incurable (but not yet critical) liver disease, knew why Mickey got the liver and she didn’t. “Once you get hospitalized you move up on the list, famous or not.” Furthermore, she endorsed his getting first shot despite his short wait. “He is fighting for his life. I’m glad he got it” (“Liver Patients,” 1995, p. A1).

Regarding the alcohol issue, doctors assured the press that confirmed abstinence was required for transplant qualification. Experts said the recidivism rate for transplanted alcoholics was much lower than that of recovering alcoholics in general (“Lifelong Drinkers,” 1995; “Mantle’s Speedy Transplant,” 1995). Klintmalm affirmed that Mickey would not have been considered had he not been sober. “This is a man who abused alcohol, understood what went wrong and took care of it,” he reminded the critics (Sherrington, 1995, p. 5B).

Others pointed out that if people with vices were disqualified from transplant consideration, many of those complaining would find themselves ineligible. “If you’re going to deny transplants and hold people responsible for their health, why single out alcoholics?” asked Martin Benjamin of the University of Michigan (“Mantle’s Speedy Transplant,” 1995, p. 3C). What about people who don’t take their blood pressure medication? Don’t exercise? Smoke? Eat too much? Practice unsafe sex? Fail to buckle up?

Shortage, not celebrity or morality, emerged as the real culprit when deciding who lives and who dies. At any given time, more than 40,000 Americans wait for organs. Each donor contributes an average of three to four organs. About 12,000 brain deaths occur per year which could result in organ donation (Manning, 1995). Looking just at the numbers, there seems to be no reason to quibble over who deserves an organ and who doesn’t. There should be enough for everyone in need.

So why do some people die waiting for organs? Only about a third of the potential cases actually become donors; that percentage substantially reduces the odds of finding a match for any given patient (Manning, 1995). The low donation rate means there aren’t enough matching organs for those who need them, famous or not. Everyone in the transplant community wanted that set of facts emphasized instead of Mantle’s presumed special treatment.

Klintmalm and his supporters gained considerable clout explaining and re-explaining the system to an impressed media. Unfortunately, even as the doctor spoke, he knew events were taking shape that would again test the credibility he so carefully nurtured. The entire medical team would grieve not only a lost patient, but also their damaged professional egos and the disappointing reversal of their efforts to educate.

When Goldstein and his assistants began surgery, they knew Mantle’s liver contained a cancerous tumor. If they discovered it had spread beyond the organ, they would abort the transplant. Another patient and another team of surgeons would receive the donor’s precious gift. Goldstein would sew Mantle up and return him to whatever life he had left (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

The team ran multiple tests to determine the cancer’s status. Every test said proceed, so the surgeons removed the sick liver and stitched in the new one. A final pathology report showed microscopic cancer cells at the bile duct. They could not remove it. Following an experimental approach which had shown promise in transplanted liver cancer patients at Baylor, the doctors administered chemotherapy both during and after the procedure. They hoped it would overcome the inoperable site as well as any undetected cells that had spread through Mantle’s system (Coleman & Spaeth, 1996).

Four days after surgery, Klintmalm described “an ordinary, normal recovery” (“Mantle to Promote,” 1995, p. 13A). In, at the worst, a sin of omission, he emphasized how well the new liver was working, diverting attention from the cancer question (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

Discussions in the patient’s room, however, exhibited less optimism. By July 13, tumors showed up in Mantle’s lungs, demonstrating that the treatment plan had not worked. Mantle insisted the information remain confidential. “Up on 14, we had a patient demanding absolute discretion,” Klintmalm described the situation. “In the lobby, we had the clamoring press and the sort of hysteria they provide. That put us in an extraordinary bind” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

On July 6, The Dallas Morning News followed Dr. David Mulligan to his home. Mulligan, who had just completed 2 years of transplant training at Baylor, assisted during Mantle’s surgery. He told a reporter that some unremovable tumor was left behind, posing risk to successful recovery (“Mantle’s Surgeon,” 1995).

Goldstein denied Mulligan’s report, dismissing the excessive pessimism of “junior people.” He stuck by his previous 85% prediction for survival after 1 year (“Mantle’s Surgeon,” 1995). Omission now distinctly resembled a lie.

“That’s where things went wrong,” Klintmalm believes. “We really had two options—to say ‘no comment,’ or to confirm the leak. You cannot lie to the press. That was bad judgment” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

By August 1, rumors forced Mantle to disclose his condition via videotape, and all hell broke loose. The press felt betrayed by the medical team they had come to trust. Klintmalm regretted the damaged alliance. Annoying as they were, journalists were powerful and necessary partners in educating the public.

Medical ethicists unanimously endorse respect for the patient’s wishes regarding dissemination of private medical information. “There would have been a backlash if doctors were too honest,” said John Burnside, associate dean and ethics instructor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (“Doctors Say,” 1995, p. 6). At every turn of events during the 9-week Mantle saga, medical and ancillary staff faced the age-old dilemma: damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

When Mickey Mantle regained consciousness after his transplant, he experienced what Klintmalm called “as close to a religious experience as he ever went through” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996). Mantle’s lawyer and 30-year friend, Roy True, sat with him 4 days after surgery. “Mickey was really in awe of the whole situation,” True remembered. Throughout his life, Mantle remained skeptical of strangers. They always seemed to want something from him. Yet, this total stranger, and the family who mourned him, gave Mickey part of himself, saved Mickey’s life, and expected nothing in return. “He felt a gigantic responsibility for having a second opportunity, and a burning desire to give something back” (True, personal communication, March 8, 1996).

Mantle asked his friend, “‘What do you know about this [organ donation]?’ I told him I knew very little. He was thirsty for information. He said, ‘Let’s go find out about it. Find out what we can do to help.’” True got a quick course in organ donor basics and reported what he’d learned. “Mickey’s first thought was to help people pay for transplants. But I told him the biggest problem is the shortage” (True, personal communication, March 8, 1996).

Mantle confirmed that assessment with Klintmalm. “Doc, what can I do? I’ll give you anything you want,” he said.

“I didn’t ask him for his autograph,” the doctor recalled. “I asked him to help promote awareness of the need for organ donation” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

So by the time Mantle shuffled into his July 11 press conference, his first public appearance since the surgery, he had three things to say:

He was grateful to be alive and particularly grateful to his anonymous donor.

He deeply regretted the way he had spent his first chance at life.

This second chance would be different; he intended to spend the rest of his life promoting donor awareness (“Mantle Is Weaker,” 1995).

He thought it might be a long life, but the treacherous cancer had other plans. It roared through his system, faster than Mantle running the baseline. In the combined 150 years of experience shared by the Baylor treatment team, none had seen a more aggressive cancer. Klintmalm shook his head, looking back months later, both awed and disgusted by the enemy’s power. “You could literally see it grow day to day, just by examining him” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

The doctors told Mantle they’d lost the battle. The blue eyes saddened, turned away, and a very sober American hero simply said, “Thank you.” He had limited time left to give something back. He wanted to get it done. “What’s taking so long?” he demanded of True, almost daily (True, personal communication, March 8, 1996).

Mickey Charles Mantle died August 13, 1995. On August 15, 2,000 people overflowed the sanctuary, chapel, and hall of Lovers Lane United Methodist Church in Dallas to bid goodbye to “Number 7.” Men, mostly in their 40s and 50s, made up three quarters of the crowd. But boys in baseball caps, reminded by their mothers to remove them in respect, also shared seats with the likes of Reggie Jackson and George Steinbrenner (“Goodbye,” 1995).

NBC Sports broadcaster Bob Costas, who had carried Mantle’s baseball card in his wallet since he was 12, eulogized his flawed idol. Country singer Roy Clark sang, as Mickey had requested, words expressive of Mantle’s acceptance of responsibility for his own errors:

Yesterday when I was young…

I teased at life as if it were some foolish game …

I used my magic age as if it were a wand

And never saw the waste and emptiness beyond …

The time has come for me to pay for yesterday

When I was young.”

It was the largest requiem for a sports hero since the death of another Yankee, Babe Ruth, 47 years before (“Goodbye,” 1995). Almost every newspaper in the country carried the story; major broadcast media carried the funeral live. Hundreds of affiliates and all network evening newscasts included tape. Millions mourned a hero, coming to terms with his flaws much as Costas did in his eulogy. “None of us, Mickey included,” he said, “would want to be held accountable for every moment of our lives. But how many of us could say that our best moments were as magnificent as his?” (“Nation Mourns,” 1995, p. 1).

Sometimes, words and actions from the famous bespeak the emotions of the common man. After the funeral, Stan “The Man” Musial, himself the hero of many St. Louis Cardinals seasons, talked to the press. He said he had once been advised to tell people what they mean to you. “The last time I saw him, I told Mickey I loved him,” Musial said. Then, tears burst from the Hall of Famer’s eyes. He abruptly turned and walked away, sobbing (“Goodbye,” 1995, p. 1A).

It took only 2 days for Mickey Mantle to make news again. The Mantle family, True, and Baylor officials announced formation of the Mickey Mantle Foundation. “The only goal we have is one Mickey would have set, and that’s an absolute home run,” True told the assembled press. “Mickey’s Team” would recruit members until they could “end the waiting list for donated organs” (Weiss, 1995, p. 27A).

The Foundation’s inaugural effort was a special organ donor card. On it, Mantle posed in classic baseball card stance. The back of the card contained a donor declaration and signature form. Before he died, Mickey approved the design of the card and the slogan for the Foundation: “Be a hero. Be a donor.” He also wrote the message on the card.

The best gift I ever got was on June 8, 1995 when an organ donor gave me and five other patients … the organs we needed to live. I guess you could say I got another time at bat.

Now I want to give something back. I can do that first by telling kids and parents to take care of their bodies. Don’t drink or do drugs… .

Second, think hard about being an organ and tissue donor if the time ever comes. Sign this card, carry it with you, and let your family know how you feel.… I’ll never be able to make up all I owe God and the American people. But if you will join me in supporting… organ and tissue donation, it would be a great start.

Volunteers, including transplant recipients and donor survivors, distributed the cards at ballparks throughout the nation over the Labor Day weekend. The Texas Rangers led the distribution by staging a 4-night promotion beginning September 1. The Mantles then flew from Dallas to New York for a similar September 5 event in Yankee Stadium (“Mantle Foundation,” 1995).

Grief counselor Larry Yeagley defines grief as “the attempt of the person to bring about equilibrium” (Yeagley, 1994). Balance is restored when one stops resisting the end of life as it was and moves on into life as it is. Carl Lewis, winner of nine Olympic gold medals in track and field whose own “Mickey’s Team” card was distributed during the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, spoke of one way to restore balance after loss by “taking an unspeakable negative and doing whatever possible to turn it into something positive” (Lewis, 1995, p. 5J).

The controversy surrounding Mickey Mantle’s transplant, his subsequent death, and establishment of The Mantle Foundation offered to various groups— fans, medical team, and those with lives directly touched by organ donation— many opportunities to restore balance by turning their own unique grief into positive action. How was each group affected by Mantle’s struggle? How did each respond? How did each response contribute to each group’s restoration of balance?

The Fans

As a symbol, Mantle’s death sealed the death of an era for lifelong fans of the game, providing final closure to the “better time” they had long mourned and enabling them to move on, to deal with the new realities. When Mickey played, baseball was America’s sport and America’s soul. The NFL provided secondary entertainment, and the NBA barely registered. By the time Mickey died, both he and baseball had lost their innocence. The innocence of a country boy disappeared in the city. The innocence of the game turned sophisticated and sour.

Mickey played for a team and for a game. Getting paid well was incredible good fortune, not an entitlement. He played baseball in that time before “free agency, investigative sports reporting, stratospheric salaries and the accompanying fan cynicism. In such a way, Mantle takes with him an irretrievable piece of history” (Strauss, 1995, p. 2B).

“He was Baseball’s flag-bearer at a time when money wasn’t the issue and loyalty was,” said one writer (Hansen, 1995, p. 1C). By August of 1995, those times were dead. Fans buried them with Mickey and faced the reality of the new game: zillionaire players and strikes and a canceled World Series. “Baseball wanted to be treated like a business, so that’s what we’ve done,” wrote Tim Wood, a fan in Texas. “But Mickey Mantle reminded us of what the game once meant to the nation” (Wood, 1995, p. 3).

On a personal level, life as a Mantle fan had long been a roller-coaster ride. Many lost their hero for the second time when he died. Disillusionment hurts. Few Americans had room in their concept of “hero” for a vision of Mantle, a golf club in one hand and a tumbler of vodka in the other, tossing crude suggestions to female spectators. “The first great disappointment in joining the sports staff here in 1967,” wrote columnist John Anders in The Dallas Morning News, “was learning that my boyhood idol, Mickey Mantle, was a big drunk” (Anders, 1995, p. 1C).

Then Mantle repented and, suddenly, he deserved admiration again. Fans had new reasons to justify their hero-worship. The “American Dream” looked a whole lot more like their own life than they had ever imagined, and they truly appreciated what it took to overcome such human frailty. “Courage is not playing baseball with bad knees,” declared writer Bill Reynolds. “Courage is announcing to the world you’re an alcoholic, especially when you are Mickey Mantle and you are supposed to be an American hero, however personally flawed you may be” (Reynolds, 1995, p. 26). “He’s more of a hero for being brave in the face of that than for the great and entertaining things he did on the ballfield,” wrote another fan (Vecsey, 1995, p. Dl).

Then, when critics questioned Mickey’s right to that liver, any still-wavering worshiper found his faith restored. Among baseball’s faithful, Mantle’s stock rebounded to previous heights. Fans had someone to cheer for again, and a few folks to cheer against. “I know all the arguments you’re going to make,” Art Lawler, among others, blasted. “Transplants shouldn’t be dispensed based on fame. Moral judgment, OK, but not fame. Alcoholics, you say, should get less consideration…. What you’re saying is people should be responsible and without vices, as you’ve always been” (Lawler, 1995, p. 1C).

Bill Lyon administered more than a tongue-lashing to the self-righteous. He issued a call to action. “Why not use your energy and passion for something far more constructive instead? Why not take the time to fill out an organ donor agreement? Why not make something good out of this?” (Lyon, 1995).

Like the hero they knew him to be, Mickey Mantle left his fans a way to make something good happen, a way to restore equilibrium. Initially, the Foundation printed 3 million Mantle donor cards. By September 8, the enormous response demanded a second printing. Potentially, a month after Mickey Mantle’s death, 3 million more people carried organ donor cards than did the month before: fans taking positive action to restore balance after a loss.

The Medical Team

Mantle brought his medical team into the world’s most unforgiving spotlight. His doctors found their integrity under attack at every turn. Some critics accused Baylor of taking the case just to make a name for itself, but doctors scoffed at that charge. No one who had experienced the media would take a high profile case for the sake of publicity. “It’s very unpleasant,” Klintmalm complained, “to work these situations, with so many unknowns, with the press breathing down your neck” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

When Mantle died, the doctors grieved the loss of a patient, one they had come to admire and care about personally. They also grieved their own failure, now exposed to the world. Repeatedly, and with varying success, they defended their professional reputations and integrity. The public scrutiny only heightened their personal loss. “His death intensified all the attacks on us for what we had done,” charged a tight-lipped Klintmalm. “And everyone’s so darn smart in retrospect” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

The team worked exceptionally hard to bring something good out of Mantle’s situation. They had established a working relationship with the press, a key to allaying persistent public doubts about the fairness of organ allocation. But, just when their integrity seemed accepted, the leak about Mantle’s cancer occurred, and the headlines said they had lied. The good they had accomplished seemed to be dying along with their patient.

“I don’t think the press has ever forgiven us for not telling them everything,” Klintmalm said 8 months after Mantle’s death, still sounding weary and just a little bitter. The media had trusted the Baylor program. He now thought they would never do it again. With a public relations nightmare on his hands, Klintmalm committed his emotional and physical being to bringing something good out of the tragedy. He does not feel he succeeded (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996).

But the doctor clings fiercely to the one victory he feels he can claim. The Mantle episode brought the issue of organ transplantation to the large segment of the American population that reads nothing but the sports pages. “Mickey gave us the opportunity to speak to them,” said the doctor. “I guarantee you, it was the first time ESPN reported on organ donation” (Klintmalm, personal communication, February 29, 1996). Because of the controversy, millions first learned about the process, and millions more carry donor cards.

Nevertheless, very little worked to ease the medical staff’s pain. With the spotlights on and the accusations flying, they had to search for quiet moments alone to deal with their grief. Public acknowledgment was not an option. As they talk, their emotional scars lurk just beneath the professional surface, visible with very little prodding.

The Transplant Community

The transplant community, as used here, includes all those personally affected by the organ donation/organ transplant process: recipients who live today with transplanted organs, potential recipients who wait for the chance for a life-saving match, and surviving families who approved organ donation when a loved one died. Of course, not all of them were baseball fans. Still, in the summer of 1995, they all shared a very special bond with Mickey Mantle and the organ transplant system he then represented.

Recipients After transplant, survivor guilt plagues virtually every transplant recipient. For example, Susan Reid, heart and double lung recipient, grieved for her donor as deeply as if she were a relative and asked herself all the “survivor guilt” questions: Did someone die so I could live? Am I worthy? What if I fail? (Reid, personal communication, September 25, 1995). Her guilt is irrational, but real nonetheless.

The Mantle controversy added heat to every recipient’s cauldron of doubts. If the system was corrupt, were they tainted as well? Did people who thought Mickey Mantle was undeserving think the same of them? The approximately 20% of all liver recipients whose organ damage resulted from alcohol problems (Bavley, 1995) had to take the attacks on Mantle’s worthiness personally. If people questioned giving an American hero a transplant because of his problem, what must people think of the recipient’s own ordinary, flawed life?

“You wouldn’t believe how many people called me,” said Sandy Sanders who received a liver transplant several years earlier. Alcohol played no role in Sandy’s illness. Nevertheless, attacks on the system upset her. “I got so angry with people talking about things they knew nothing about, as if they were experts. And, I don’t understand people who think they should get to decide who gets a chance to live” (Sanders, personal communication, February 25, 1996).

The last thing Sandy needed was the hint, even indirectly through Mickey, that someone else should have gotten her liver. She vociferously defended the system’s integrity. “There is nothing rich or special about me. I had the same doctors, in the same hospital, and I waited 2 days” (Sanders, personal communication, February 25, 1996).

Sandy and others needed the public to understand that a short wait for an organ just means the recipient is really, really sick. As detailed earlier, many recipients took the opportunity to act during the Mantle controversy, a time-honored tool for emotional recovery. They spoke about their experiences in print and broadcast media all over the country, contradicting accusations of special treatment. They staffed tables at baseball games after Mickey’s death, whether they liked baseball or not, to distribute donor cards and answer questions from anyone who asked. Speaking out and participating helped justify their good fortune in living, providing them a way, as Mickey said, to give something back.

(Alcoholics who had received transplants may not have felt as free to use community action as an aid to recovery. Extensive research for this chapter, reviewing hundreds of pages of editorial content from across the nation, uncovered not one example of a recovering alcoholic—or even a friend or a relative— willing to offer living proof that those with Mickey’s problem deserved a second chance. While there surely were some such examples, they must have been few and far between to be so blatantly absent from this review.)

Potential Recipients For those waiting for organ transplants, criticism of the system’s fairness hurt even worse, for it meant losing faith in their future. Suddenly, accusations flew concerning the grossest disregard for human life, accusations hurled at the very people who held the lifeline of hope. Could potential recipients trust the people they had to trust with their lives? Was it possible they would die waiting for an organ because someone famous, like Mickey, was considered more valuable?

Those who waited also knew that they needed as many chances for a match as possible. So, every time a talk radio caller declared he’d torn up his donor card because he was sick of seeing organs go to rich drunks, a listener on the waiting list winced. Each torn-up card became, literally, a lost opportunity for life.

But the combined forces of Mantle’s fame, press interest, and the medical community’s educational commitment gave individuals like Cindy Jensen opportunities to help restore balance. Doctors had diagnosed Jensen’s incurable liver disease 5 years before, but, because the demand for organs so exceeds the supply, her condition had to worsen significantly before she could get on the transplant list. She spoke out on donation during the Mantle fracas. “Being able to do this makes me feel there is a reason and a purpose to my situation. I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing while I’m waiting” (Emerson, 1995, p. B1). Taking action to increase public awareness of the need for organ donation helped potential recipients deal constructively with the uncertainty of their lives. Mantle’s fame provided them opportunities.

Donor Survivors Mickey Mantle’s situation provoked a painful deja vu for those whose loved ones became organ donors when they died. The survivors relived their own tragedy every time they flipped on the car radio or opened the paper. Rich Bender, for example, lost his 48-year-old wife in 1991. Still, each time he hears about a transplant, “I relive everything,” he says. “I am in the emergency room, holding Mary’s hand” (Bender, personal communication, February 14, 1996).

The controversy surrounding Mantle made the pain even worse. The decision to donate a loved one’s organs can aid in grief recovery. Survivors take comfort from the good they have done. Friends and relatives reinforce and praise them for the honor they brought to their loved one. It all helps balance senseless tragedy (Lynda Harrell, donor mother, personal experience; communications with multiple donor survivors).

But, as donor survivors relived their own tragedy during the Mantle coverage, the pain returned, this time without the reward. Large parts of the public condemned the donation process. Bender took it personally when people attacked the organ donor system. “I made that decision. I am part of that system,” he said (Bender, personal communication, February 14, 1996).

Then one night, in the midst of the controversy, Mickey Mantle talked to his friend, Roy True. Mantle never considered himself a proper hero. He spoke of the awe he felt for his donor, a man who had saved six lives, and for the donor’s family. “Those are the real heroes, Roy,” Mantle exclaimed. “Somebody ought to know that!”

“That’s where we came up with the slogan,” True explained. “Be a hero. Be a donor” (True, personal communication, March 8, 1996). Publicly, officially, and for all time to come, Mickey Mantle sanctioned the selfless courage of the act. An American hero restored Rich and Mary Bender, and thousands like them, to their rightful places of honor.

Activity, too, can aid the healing process. The increased discussion gave donor families chances to speak out positively for donor awareness, whether it was in private conversations, as part of educational efforts, or by staffing volunteer tables at distribution events such as those at the ballparks. To Ardell Richardson, a mother whose son touched the lives of over 100 people through organ and tissue donation, Mantle “gave us all more opportunity to promote the good we made come from our tragedy” (Richardson, personal communication, February 17, 1996).

Bob Costas distinguished between Mickey Mantle, the role model, and Mickey Mantle, the hero. “The first, he often was not,” he said in his eulogy. “The second he will always be” (“Courage at the End,” 1995, p. 79).

In spite of his accomplishments, his fame, his fortune, Mantle’s life remained that of a humble, flawed man. He managed to achieve true role model status in death. Mantle demonstrated how to take a grievous loss—his own life—and produce something good: his legacy. He gave something back, in a way that restored balance to what came before. When “donors” are “heroes,” they move from passive resource to active contributor. When “donors” are “heroes,” more people are likely to declare their wishes before tragedy strikes, more lives are saved, and more survivors are able to balance their grief.

Mickey Mantle saved his best for his ninth inning. He died a model of action in the face of adversity, leaving those who mourn a way to recover.

Anders, J. (1995, August 16). In the end, Mickey Mantle was a real hero. The Dallas Morning News, p. 1C.

Anderson, D. (1995, June 8). Hard-fought sobriety late in life couldn’t cure Mantle. American Statesman (Austin, TX), p. 1.

Bavley, A. (1995, June 8). No “playing God” with transplants. Kansas City Star, p. A-1.

Bray, S. (1995, June 18). Did Mantle deserve his transplant? The Olympian (Seattle, WA).

Brown, D. (1995, June 9). Mantle gets liver transplant. Review Journal (Las Vegas, NV).

Burke, C. (1995, June 9). “Blame” luck, not celebrity. New York Post, p. 8.

Coleman, J., & Spaeth, M. (1996, Spring). Transplanting the Mick’s liver. The Public Relations Strategist, 2(1), 53.

Courage at the end of the road. (1995, August 28). People, 79.

Doctors say misleading media about Mantle justified. (1995, August 20). Daily Progress (Jacksonville, TX), p. 6.

Duskey, G. (1995, June 10). Who are we to say no to living? Alexandria Daily Town Talk (Alexandria, VA).

Emerson, J. (1995, June 9). While Mantle gets new liver, Jensen waits. Register Star (Rockford, IL), p. B1.

Experts: No favoritism for Yankee great’s transplant. (1995, June 12). Boston Herald.

Goodbye to no. 7. (1995, August 16). The Dallas Morning News, p.lA.

Goodstein, L. (1995, June 10). Mantle: One strike & you’re out? Washington Post, Dl, D4.

Gregg, B. G. (1995, June 9). Mantle gets liver—but no favoritism. Cincinnati Enquirer.

Hansen, G. (1995, June 9). Yanks’ no. 7 will always be a hero. Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, AZ), p. 1C.

Herskowitz, M. (1995, August 15). All my Octobers. Reporter News (Abilene, TX).

Hoffer, R. (1995, August 21). Mickey Mantle. Sports Illustrated, 83(8), 25ff.

Hopper, K. (1995, August 15). “The Mick” mementos. Star-Telegram (Fort Worth, Texas), p. 1, Business Section.

Kochik, R. (1995, June 24). Mantle would have had the same wait for a liver here. Philadelphia Inquirer.

Lacy, T. (1995, June 9). Mantle transplant angers donors. Nevada Sun (Las Vegas), p. 3A.

Lawler, A. (1995, June 11). And now for Mick’s leverage. Idaho Statesman (Boise, ID), p. 1C.

LeBreton, G. (1995, June 9). Protest over Mantle getting liver transplant unfounded. Star-Telegram (Fort Worth, TX), p. 1.

Levy, D. (1995, October 20). Transplant decisions are based on need, not celebrity. USA Today, p. 3D.

Lewis, C. (1995, August 27). Be a superstar in the game of life and join Mickey’s team. The Dallas Morning News, p. 5J.

Lieber, J. (1995, October 18). Mick’s friends mourn with fond memories. USA Today, p. 1C.

Lifelong drinkers must meet the test to get liver. (1995, July 8). The Tennessean (Nashville, TN).

Lipsyte, R. (1995, June 9). Commentary. Daily News, p. 1.

Liver patients express gladness, concern about Mantle’s short wait for a transplant. (1995, June 9). The Courier-News (Elgin, IL), pp. Al, A6.

Lyon, B. (1995, June 9). Body and spirit, a salvage job. Philadelphia Inquirer.

Manning, A. (1995, October 20). Mantle’s family sets up organ donor program. USA Today, p.3D.

Mantle foundation says 3 million donor cards distributed to date. (1995, September 8). Transplant News, p. 2.

Mantle is weaker but wiser. (1995, July 12). The Dallas Morning News, p. 1B.

Mantle lucky to get on list. (1995, June 9). Tampa Tribune, p. 10, Nation World Section.

Mantle, M. (1994, April 18). Time in a bottle. Sports Illustrated, 80, 66–76.

Mantle to promote organ donations. (1995, June 12). The Dallas Morning News, p. 13A.

Mantle’s speedy transplant raises ethical points. (1995, June 9). USA Today, p. 3C.

Mantle’s surgeon discounts assistant’s gloomy comment. (1995, July 9). Star-Telegram (Fort Worth, TX), p. 19, Metro Section.

Mantle’s wife bares agony over life with Mick and the bottle. (1995, June 9). New York Post, p.75.

Matthews, W. (1995, June 11). It’s sick when a doctor has to say “sorry” for saving a life. New York Post, p. 5.

Mickey Mantle: 1931–1995. (1995, August 14). The Dallas Morning News, p. 1A.

Mickey Mantle defined the word “hero” for a generation. (1995, August 14). Gazette (Texarkana, TX).

Mickey Mantle’s liver is on readers’ minds. (1995, July 7). Free Press (Detroit, MI), p. 7F.

Myerson, A. R. (1995, June 13). Reality strikes home for Mantle family. Arizona Republic (Phoenix, AZ).

Nation mourns death of baseball hero Mickey Mantle. (1995, August 15). Transplant News, 5(15), p. 1.

Operation goes “well,” docs say. (1995, June 9). New York Daily News, p. 7.

Poirot, C. (1995, June 13). Mantle transplant spotlights donation. Fort Worth Star Telegram, p. 3.

Reynolds, B. (1995, June 11). As Mantle knows now, alcohol abuse leaves no prisoners. Journal (Providence, RI), p. 26.

Sherrington, K. (1995, June 20). Family pulls together around Mantle during ordeal. The Dallas Morning News, p. B5.

Sherrington, K., & Rogers, P. (1995, August 14). Baseball great Mickey Mantle dead at 63. The Dallas Morning News, p. 1A.

Some exploit edge in organ “shopping.” (1995, June 9). Atlanta Constitution.

Sorensen, T. (1995, June 8). Mantle was life in 1950s American (Odessa, TX), p. 18.

Thompson, J. (1995, June 17). Viewpoint letters. Los Angeles Times, p. 17.

Stein, G. (1995, June 9). Everyone’s an expert on Mantle’s liver. Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, FL), p. C2.

Strauss, J. (1995, August 14). Mantle carried Yankees, heavy burden of personal tragedy. The Lufkin Daily News, p. 2B.

Vecsey, L. (1995, June 9). Mantle still can be hero. The Phoenix Gazette, p. Dl.

Weiss, J. (1995, August 18). “Mickey’s team”: A ballplayer’s legacy. (1995, August 18). The Dallas Morning News, p. 27A.

Wood, T. (1995, August 18). Weatherford watch. Democrat (Weatherford, TX), p. 3.

Wrolstad, M. (1995, July 12). Give and take situation. The Dallas Morning News, p. 25A.

Yeagley, L. (1994). Grief Recovery, Charlotte, MI: Author. (5201 N. Stine Road, Charlotte, MI 48813).