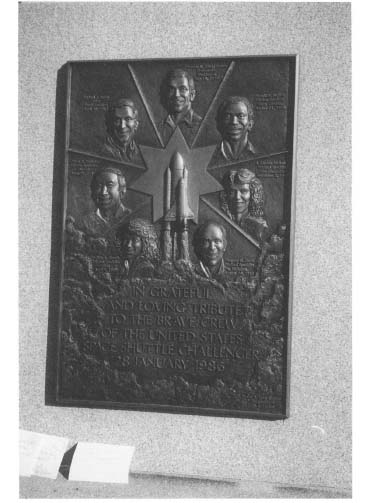

Figure 2.1 Challenger memorial in Arlington National Cemetery (Sec. 46), one of hundreds erected nationwide to honor the crew of the ill-fated spacecraft. Plaque on front shows the faces of the seven astronauts and mission specialists on board and reads “In Grateful and Loving Tribute to the Brave Crew of the United States Shuttle, Challenger, 28 January, 1986.” Note cards at base of memorial are messages left by anonymous visitors. One writes: “We wish you to rest in peace and thank you for your courage.” (Personal photo of author.)

The Challenger Disaster: Group Survivorship on a National Landscape

Few events are of such consequence as to affect the memory of a nation. In the history of the United States over the last half-century, only the Kennedy assassination equals that of the Challenger explosion in having made an indelible impression on all those who lived through the tragedy and its aftermath. For the generation of Americans born in the 1970s, the tragedy of the Challenger shuttle and its crew, witnessed live on television (as it was by an estimated 40% of late elementary and secondary students; Clymer, 1986), holds special significance as a primary national loss.

When the Challenger exploded 73 seconds after launch on January 28, 1986, where were you? Most people can readily answer that question. The Challenger explosion not only was a genuine tragedy in the loss of life of its seven crew members and posed a real threat to the future of the U.S. manned space program, but it was also “one of those rare events that sear the nation’s soul” (Cook, 1996, p. 11). On the one hand, the accident represents a failure of technology and of organizational communications, according to the findings of the Rogers Commission established by then-President Reagan to investigate and report on the cause of the explosion. Of significance, too, however, is that the loss of the Challenger shuttle generated a prime example of group survivorship on a broad scale. How and why the Challenger disaster became a nodal loss for many Americans and how bereavement was addressed within many diverse survivorship groups is the focus of this chapter.

THE SHUTTLE CHALLENGER: MISSION 51-L

NASA’s Shuttle Program The National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA), created to respond to Russian space accomplishments in the 1950s, was in its 28th year at the time of the launching of Challenger in January 1986. Mission 51-L marked the 25th time that a reusable manned shuttle had been employed and the 10th launching of the Challenger ship. Challenger, first launched in 1981, and its sister ships, Columbia, Discovery, and Atlantis, were considered the “most advanced space transportation technology in the world. No other nation had achieved a reusable spaceship that could maneuver inside and outside the atmosphere and lift payloads with an earth weight of 32 tons” (Lewis, 1988, pp. 2–3).

Mission 51-L The mission of Challenger that January was to have lasted for approximately 7 days, with a return landing at the Kennedy Space Center scheduled for a little more than 144 hours after launch. On board were the Haley’s Comet Experiment Deployable, a satellite designed to observe the flyby of Haley’s Comet; a shuttle-controlled astronomy tool; fluid dynamics experiments to be carried out by a civilian engineer employed by the Hughes Aircraft Company; and three student-designed experiments. Additionally, a set of lessons designed for the Teacher-in-Space Program to be delivered in a live broadcast from space by the first ever teacher/astronaut heightened public interest in this particular fight. Two lessons were planned: “The Ultimate Field Trip,” a description of life aboard a space shuttle, and a second exercise explaining ways of exploring space and manufacturing new products utilizing zero gravity.

Two aspects of Mission 51-L made it unprecedented. The first was the inclusion of Sharon Christa McAulliffe, the “teachemaut,” listed as the Challenger’s Payload Specialist 2. Generally known by her middle name, Christa was a high school social science teacher from Concord, New Hampshire, who had been among the 10,000 teachers who had applied for the Teacher-in-Space Program first announced by President Reagan. Described by reporters as articulate and personable, she had been in training for the mission for over 5 months.

The second special feature of this mission was the diversity of the entire Challenger crew for Mission 51 -L. Dubbed the “all-American” crew, the seven-member crew was composed of five men and two women and included African-American, Asian-American, and Jewish astronauts who seemed to “represent Everybody’s America” (Wolfe, 1986, p. 40). Crew members consisted of the shuttle commander, Francis R. Scobee, an Air Force test pilot; the shuttle pilot, Michael J. Smith, a Navy-trained test pilot; Mission Specialist 1, Ellison S. Onizuko, the first American astronaut of Japanese descent; Mission Specialist 2, Judith A. Resnik, the second woman to have flown in space; Mission Specialist 3, Ronald E. McNair, the second African-American astronaut; Payload Specialist 1, Gregory Jarvis, a civilian engineer; and Christa McAuliffe, representing the Teacher-in-Space Program.

Mission Delays Originally scheduled for a late December 1995 launching, 51-L had been delayed or scrubbed a total of five times before actual launch. Delays in the previous Columbia mission had pushed the launch date into January. Poor weather conditions, both at the Kennedy Center or at alternative emergency landing sites in Africa, had forced further delays. The Sunday, January 26th postponement permitted some of the crew members to watch the SuperBowl match-up between the New England Patriots (McAuliffe’s home team) and the Chicago Bears that night (Broad, 1986). On Monday, January 27th, an exterior handle on the crew compartment door could not be properly latched and had to be cut away, but only after several hours delay while a replacement battery for the handheld saw was located. The series of delays was reported with some frustration and annoyance by the press. Vice President Bush, on hand for the Monday launch, could not stay for the rescheduled Tuesday take-off. Although denied by the White House, some still believe there was political pressure to press for a launch by Tuesday to allow President Reagan to use its success in his State of the Union address scheduled for Tuesday evening. Moreover, there was some concern that further postponements might interfere with the 15 other shuttle missions planned for 1986 and a planned May launching of Challenger that depended on the position of the planet Jupiter for its mission success (Lewis, 1988).

Launch Day Tuesday, January 28th was clear and cold with acceptable wind conditions for launching. Overnight temperatures had fallen to the low 20s, causing icicles to form on the mobile launch platform and chunks of ice to cluster in the overpressure water troughs below the platform. The seven crew members were in place aboard the Challenger an hour before a set 9:36 a.m. launch, but Mission Control ordered a 2-hour hold to allow rising temperatures to melt some of the ice. When an ice inspection team reported favorable conditions, the countdown was continued. Temperature at launch had risen to 36° Fahrenheit (Lewis, 1988).

At 11:38 a.m., Challenger, attached to its external fuel tank and twin solid rocket boosters, was launched. According to initial telemetry data received in Houston and from the view of cameras and those watching from reviewing stands on the ground, all appeared to be normal. But, at 70 seconds into launch, a NASA camera recorded an orange glow that expanded into a yellow-orange flame on one side of the external fuel tank. Within seconds, a huge fireball engulfed the shuttle, the fuel tank, and both solid fuel rocket boosters. At T plus 1:13, 73 seconds into launch, the last recorded words from a Challenger crew member, Pilot Michael Smith, were heard: “uhh … oh.”

From the ground, the fireball and its gray-white vapor trails were clearly visible to the 1,000 VIPs, family members, and guests who had been invited to witness the event from the reviewing stands situated almost 4 miles from the launch pad (Magnuson, 1986a). The solid rocket boosters flew away from each other, leaving a ragged Y-trail in the sky. Dark smoke clouds filled the sky and falling debris was visible on monitoring cameras. Clearly visible moments later, too, was a single parachute drifting slowly downward, leading many in the stands and on TV to believe that the crew may have been spared. But the parachute was only part of the recovery system for the solid rocket boosters which had been destroyed by Mission Control when they went out of control. For a moment, the voice of Stephen Nesbitt, Public Affairs Officer, was silent. Nesbitt then reported over the loudspeaker system to all those witnessing the event: “Flight controllers are looking very carefully at the situation. Obviously a major malfunction. We have no downlink. We have a report from the flight dynamics officer that the vehicle has exploded” (Lewis, 1988, p. 21).

Recovery efforts were begun immediately by Naval and Coast Guard ships which had been in place for the planned recovery of the twin solid rocket boosters. Ultimately, 31 ships, 52 aircrafts, and 6,000 workers would be employed in recovery efforts over the next 4 months (Dowling, 1996). It would become the “largest salvage operation in world maritime history” (Lewis, 1988, p. 142); about one third of the entire shuttle would be recovered. Christa McAulliffe’s lesson plans, intact and dry within a plastic bag, were recovered within the first few days, the crew compartment and bodies, 2 months later (Thomas, 1986).

Investigation Into Cause Within 3 days of the explosion, information gleaned from close review of film and telemetry data turned the focus of NASA’s investigation toward a defective field joint on the right solid rocket booster. The field joint was part of the assembly, completed at the Kennedy Space Center, of the 149.5' rocket booster following manufacture of the solid rocket fuel and four motor segments in Utah by Morton Thiokol Inc. Reagan appointed The Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident on February 3. Led by William P. Rogers, former Secretary of State under Nixon, and popularly known as the Rogers Commission, it moved control of the investigation away from NASA and pledged to make all information about the explosion available to the public. Televised public hearings began within days. From internal NASA documents leaked to the press and examined publicly by the Commission panel soon thereafter, it quickly became apparent that NASA had noted problems with the rubber O-rings in the solid rocket booster joints as early as 1981, 5 years before the explosion.

The Rogers Commission ultimately determined that, within the first second of launching, hot gas at a temperature of 5,600°F had escaped past a lower O-ring of the right solid rocket booster, quickly melting or severing the attachment brace between the booster and the external liquid fuel tanks. Based on visual inspection of the recovered parts of the right booster, it was determined that over 6 square feet of joint had been burned away. Freed from its brace, the end of the booster had rotated outward, smashing its nose into the external tank, which then ruptured. Escaping liquid propellant ignited into a fireball. The Commission also reported that the low temperatures prior to and at the time of launch, which made the O-rings less resilient and less able to contain gases as designed, contributed to the malfunction (Lewis, 1988).

The Commission concluded that the explosion was the result of a flawed design unacceptably susceptible to a number of factors including outside temperature, deterioration following multiple usage, and probable water seepage at the joint. Challenger had been on the launch pad for over 37 days while a total of 7 inches of rain fell. The report found Morton Thiokol Inc. blameworthy of poor engineering and lack of verification of design specifications and pointed critically to the lack of specific safety monitoring within NASA. Further, the Rogers Commission pointed out what it termed “managerial rashness” for NASA to have set up an overly demanding launch schedule for 1986 which only served to increase scheduling pressures and to decrease prudent decision making. “The committee is not assured that NASA had adequate technical and scientific expertise to conduct the space shuttle program properly” was a final Commission censure (Lewis, 1988, p. 232).

Immediate Responses to the Challenger Disaster

News media coverage of the Challenger disaster was extensive, focusing both on the technological failure and on its emotional impact. But from the beginning, the failure of the Challenger was recognized as having a broad and serious impact on the nation as a whole and numerous related subgroups. Wrote one reporter, “The shuttle explosion left a psychological wake that ripples from those closest to the astronauts and NASA to our entire American people” (Goleman, 1986, A11). Both at the time of the explosion and in 10th anniversary remembrances, many Americans likened the event to their experience of the assassination of President John Kennedy in 1963. People across the country noted a silence that immediately overcame workplaces and schoolrooms of children, and the stopping of classes or regular routines. Many talked about being in stunned disbelief. The public’s strong need to know the cause and to have an explanation of why the unthinkable could happen was explained by one trauma researcher as a way to “assuage such insecurities” arising from an unexpected disaster (Goleman, 1986, A11).

Next-of-Kin Family members who witnessed the explosion in the reviewing stands at the Kennedy Space Center were quickly removed from the view of cameras and reporters’ questions and put on waiting buses. They were some time later taken back to hotel rooms. None of the articles reviewed mentioned whether these families received a formal debriefing or not. Vice President Bush, at the request of President Reagan, returned to Cape Canaveral to speak with the families of the crew. He was joined by two U.S. Senators, John Glenn of Ohio and Jake Garn of Utah, both of whom had previously flown in space, and the acting Administrator of NASA, William Graham (Boyd, 1986). Within days, NASA flew family members back to their homes, each family accompanied by an astronaut who would be on hand to answer their questions, assist with immediate arrangements, and handle the inpouring of mail and requests for interviews. Thousands of cards and letters were sent to immediate family members of the crew. Within a week, memorial funds were established across the country for the 11 children of crew members.

National Response At the national level, President Reagan addressed the country by TV late Tuesday afternoon, within hours of the explosion. In a brief statement, Reagan set the tone for national mourning. He identified each of the crew members by name and praised their courage. He acknowledged the grief of immediate family members but added that “we mourn their loss as a nation together,” and spoke directly “to the school children of America who were watching the live coverage of the shuttle’s takeoff” (“President Expresses,” 1986, p. A9). Reagan affirmed that the nation had become complacent about NASA successes and so had been taken by surprise, but he pledged a continuation of the space program in saying that “the Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we’ll continue to follow them” (“President Expresses,” 1986, p. A9). Reagan postponed the annually delivered State of the Union address scheduled for that night. Speaker Tip O’Neill recessed the House of Representatives on Capitol Hill.

Across the country, recognition of the loss of the Challenger was immediate and diverse, and many ritual observances occurred. Common was the lowering of flags to half-staff and shared moments of silence (Rimer, 1986). In Atlanta, daytime motorists turned on their headlights. In Los Angeles, the Olympic torch was relit. The Governor of Illinois asked his citizens to turn on their porchlights as a tribute to the lost crew. In New York City, the outside lighting of the Empire State Building was dimmed. Along the Florida coast, over 20,000 citizens shone flashlights into the sky on Friday night (Magnuson, 1986a).

In communities and within institutions that had special connections with individual crew members, special ceremonies and memorial services were held within the first few days. At Framingham State College in Massachusetts, from which Christa McAuliffe received her undergraduate degree, a service of over 1,000 people was addressed by the state Governor and concluded with the release of seven black balloons. The Governor of Ohio spoke at services held in the temple attended by the Resnik family. At North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro, Rev. Jesse Jackson addressed a memorial service for its alumnus, Ron McNair. The National Education Association announced that it would seek memorial funds to underwrite a special projects program in McAuliffe’s honor

Concord High School, where Christa McAulliffe had taught, and, indeed, the entire town of Concord, received particular attention. Even though reporters, who had been assigned to cover student reactions to the launch at McAulliffe’s high school, had been immediately asked to leave following the explosion, interviews with Concord students and McAuliffe neighbors were frequently reported (Wald, 1986a). Students tied black ribbons to a tree outside Concord High. Hundreds of floral wreaths lined the school halls. President Reagan sent a letter of condolence to the high school which was read at a special assembly held on that Friday, January 31st (“President’s Letter to Concord,” 1986). The mayor of Concord, who led a memorial service held at the Statehouse Plaza in Concord, accepted hundreds of letters, poems, artwork, and cards on behalf of the town (Wald, 1986c).

The major national memorial service was held in Houston at the Johnson Space Center late on Friday morning, January 31st. President and Mrs. Reagan, along with over 90 members of the U.S. Congress, attended the ceremony. The President and his wife met with family members of the deceased crew before the service and escorted them to the front rows of the outdoor seating. Witnessed by an estimated 6,000 NASA employees and 4,000 family members and guests at the service itself and by millions of Americans via live television broadcast, President Reagan’s presentation echoed themes he had drawn in his initial response on the day of the explosion (Weintraub, 1986). On behalf of the nation, he expressed his sorrow to the families and noted “the brave sacrifice of those you loved and we so admired.” He emphasized the national sense of grief, generated and expressed through public media: “Last night, I listened to a call-in program on the radio. People of every age spoke of their sadness…. Across America, we are reaching out, holding hands and finding comfort in one another.” Reagan also drew strong analogies to the pioneering history of America and the new frontiers of space, promising the lost crew that “their dream lives on; that the future they worked so hard to build will become a reality” (“Transcript,” 1986, A11). Following Reagan’s address, NASA T-38 jets flew in missing man formation over the audience while an Air Force band played “God Bless America” (Weintraub, 1986).

NASA Response Both President Reagan and Vice President Bush recognized NASA as a group particularly affected by the shuttle misfortune. Reagan addressed the agency directly in his immediate response to the nation on Tuesday, when he said that he wished he “could talk to every man and woman who works for NASA or who worked on this mission” and tell them that both their past professionalism and present pain were recognized (“President Expresses,” 1986, A9). Bush talked with about 200 NASA workers at the Kennedy Center following his visit with the families of crew members late on the afternoon of the explosion (Boyd, 1986). Schoolchildren in numerous classrooms took time to send sympathy notes to the agency. So, too, did Soviet cosmonauts (Magnuson, 1986a). A memorial service was conducted within view of the Challenger launch pad on the Sunday following the explosion at the Kennedy Space Center. Over 3,000 NASA employees and family members were in attendance as the Director of the Center, Richard G. Smith, pledged to honor the Challenger crew with a minute of silence every January 28th at 11:39 a.m. At the appointed time, taps were played for those in the reviewing stands and a large floral wreath was dropped by helicopter 2 miles out to sea (Schmidt, 1986).

Outside Response International response reflected world recognition of the significance of the Challenger accident for the United States. Numerous international leaders sent letters of condolences to the White House. One newspaper in the Soviet Union wrote that “America is frozen in shock. It seems that the flow of time in this country has been broken for several days. As Americans themselves say, at no time since the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963 has the country been so tragically benumbed” (Schmemann, 1986, p. 16). On Sunday, the Soviet Union announced that it would name two of the craters on Venus after Judith Resnick and Christa McAulliffe. In Vatican City, Pope John Paul II led thousands in prayer for the astronauts. In Japan, national TV news was expanded and devoted to the explosion coverage.

Later Memorialization

The immediate response to a major crisis is not always the truest measure of its significance. The magnitude of an event can be measured and, at the same time, enhanced by the creation of more permanent memorializations. Many occurred in the weeks and months that followed the explosion of the Challenger.

Next-of-Kin In an effort led by June Scobee, widow of the Challenger commander, family members of the crew founded and continue to help direct a foundation that promotes Challenger Centers for Space Science Education. The Centers, designed to serve as “living memorials” to the crew, offers hands-on education to schoolchildren, allowing them to participate in simulated space missions and space science experiments (Dowling, 1996). The original $30 million dollar fundraising effort was started with contributions from Morton Thiokol Inc. and other space-related private companies. The first Challenger Center was opened in 1988 in Houston, Texas, at the Museum of Natural Science. As of 1995, 25 centers had been opened across the United States and Canada, with another half-dozen centers in the planning stage. Serving as center educators are many of the 114 finalists in the Teacher-in-Space Program. One of the earliest centers was located at Framingham State College, McAuliffe’s alma mater.

Grace Corrigan, mother of Christa McAuliffe, raises money for the Challenger Centers through hundreds of lectures and from profits from her 1993 book, A Journal for Christa (Dowling, 1996) The brothers of Ronald McNair manage a nonprofit foundation in his name aimed at increasing children’s exposure to science (Swarns, 1996). The parents of Gregory Jarvis are involved with the Astronaut Memorial Foundation at the Kennedy Space Center near where they live.

National Response Across the country, especially in the communities of individual astronauts, buildings and community sites were named after the crew. The name of Challenger was given to dozens of elementary and middle schools built in the ensuing years. There is the Michael J. Smith Airport in Beaufort, North Carolina. In Lake City, South Carolina, in addition to the Ronald McNair Junior High School, there is a McNair Memorial and a McNair Boulevard (Swarns, 1996). In California, the Air Force named their satellite control center in Sunnyvale after Mission Specialist Ellison S. Onizuko. In Florida, fees from commemorative automotive license plates raised the $16 million needed to establish the Astronauts Memorial Foundation which financed a granite monument to all 16 Americans who have died while working on space projects and an educational center as well. Both are located at the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral (“We Remember,” 1996). Another national monument was erected at Arlington National Cemetery, near the Capital in Washington, DC. In mid-1987, the U.S. Geological Survey Board on Geographic Names approved a request to name a high ridge of the Kit Carson Mountain in Colorado “Challenger Point.” A plaque was laid on the ridge, “In Memory of the Crew of Shuttle Challenger” a few months later (Eberhard, 1994).

In the city of Concord, The Christa McAulliffe Planetarium offers free admission and special workshops for teachers and their families (“Christa McAulliffe Remembered,” 1996). The Christa Corrigan McAulliffe Center for Education and Teaching Excellence, also in Concord, supports innovations in science teaching.

10th-Anniversary Commemorations

While brief tributes were held annually to mark the date of the Challenger explosion, particularly at the Challenger Space Centers and at NASA space facilities, the 10th anniversary was commemorated by numerous special ceremonies to mark the occasion of the loss. Speaking the day before the decade anniversary, January 27, 1996, President Bill Clinton, in his regular Saturday radio broadcast, asked Americans “to remember together a tragedy … that tore at our nation’s heart” (“Clinton Remembers,” 1996). He spoke of the sacrifice of the Challenger crew “not in the name of personal gain, but in the pursuit of knowledge that would lead to the common good.” Mrs. Corrigan, Christa’s mother, made herself available to the public in a chatroom that evening on an international on-line service, saying that this was “the type of thing Christa herself would do” (“Christa McAuliffe’s Mom,” 1996).

Memorial ceremonies were held at 11:39 a.m. Sunday morning at the Johnson Space Center in Houston and at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, where Gregory Jarvis’s father was the keynote speaker. Seventy-three seconds of silence were observed at both sites. In Florida, a wreath was again dropped into the Atlantic off-shore, this time by James Harrington, a NASA manager who had worked on the Challenger 51-L mission. (“Media Coverage,” 1996). In Houston, at a NASA observance closed to the general public, seven bells tolled for the crew, flags were at half-staff, and family members left flowers around a central flagpole. Watched by millions of Americans on TV, a special tribute was held just prior to SuperBowl XXX in Tempe, Arizona, when Air Force F-16 fighters flew over the stadium in missing man formation. Captain Rich Scobee, son of the Challenger shuttle commander, piloted the lead plane. Events and exhibits dedicated to individual crew members were held in various parts of the country.

At Christa McAuliffe’s grave in Concord, New Hampshire, visitors left flowers, gifts, and apples. Students at Concord High walked the mile from their school to the Capital Center for the Arts to hear a presentation by a Concord alumna who had been a news reporter covering the launch 10 years before. A new exhibit on the life of McAuliffe was unveiled at the planetarium in Concord (“Christa McAuliffe Remembered,” 1996).

Much attention was paid to how the families of the crew had fared over the ensuing decade. Lengthy articles appeared in magazines and newspapers describing remarriages of spouses and current interests of their children (Dowling, 1996; “Their Families Today,” 1996). And, according to a list of anniversary events maintained on the internet by the Ontario Challenger Centre, the families made themselves available to the public, appearing on over a dozen TV news shows and granting interviews for national and local newspapers (“Media Coverage,” 1996).

GROUP SURVIVORSHIP AND THE LOSS OF CHALLENGER

“The nation came together yesterday in a moment of disaster and loss,” wrote one New York Times reporter the day after the explosion (Rimer, 1986). For younger Americans, the Challenger explosion was seen as a national event that took away innocence and faith and brought in a heavy dose of reality. On the 10th anniversary, the Houston Chronicle invited its readers and Houston Chronicle Interactive internet service users to share their memories of the Challenger explosion. Amy Chen, a graduate student at University of California at Berkeley, wrote:

Many people consider the assassination of President John F. Kennedy as the one moment in history that they will never forget. Since I was not even born at that time, I could never truly understand the emotions and memories of that tragedy, until the Challenger accident. For me, Challenger will always be the one defining moment in history that I will remember. (“We Remember,” 1996)

What factors contributed to this tragedy becoming such a notable marker in recent American history? This section of the chapter will examine why the Challenger explosion was such a significant historic event and will analyze how the reactions of diverse groups of survivors are reflected by one model of group survivorship.

A NODAL LOSS FOR THE UNITED STATES

Trust in NASA and in Space Technology NASA’s solid reputation, built on a string of well-publicized successful missions, contributed to the shock and disbelief engendered by the news of the Challenger failure. NASA had been known as an organization that exemplified open communications and nonhierarchical organization, allowing for the free flow of innovative ideas so necessary to the building of a cutting-edge space program (Schwartz, 1987). Under its administration, NASA had made the wonders of space travel commonplace. Even the near disaster in April 1970 of Apollo 13, whose moon-bound mission was brought safely back to earth despite the explosion of oxygen tanks on board, only served to increase belief in NASA know-how (Wainwright, 1986).

The Challenger disaster marked the first time that an astronaut had died while in flight, although other space employees had died while working in the space program. Most publicly known were the deaths of Apollo I astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee in a 1967 fire while in a training session on the launch pad at the Kennedy Space Center. But school-age children had no memory of this early tragedy, occurring as it did just 9 months before the assassination of Robert Kennedy.

Shuttle flights had become routine. Even the word shuttle implied a certain ordinariness. No longer considering shuttle technology to be experimental, NASA had declared the shuttle “operational” in July 1982, following the fourth test flight of the space shuttle Columbia (Lewis, 1988). Not surprisingly, the launch of Mission 51-L drew relatively limited coverage despite the publicity over its teacher crew member, with only CNN and NBC’s Today Show, in its West Coast early morning broadcast, providing live coverage of the launch (Wright, Kunkel, Pinon, & Huston, 1989). The shuttle was both an impressive accomplishment of American technology and something relegated to the inside pages of the nation’s newspapers.

Special Attributes of the Crew Despite the fact that the shuttle flights had become somewhat routine, Americans developed a special connectedness and identification with Mission 51-L and its crew members. NASA had created the idea of a “citizen observer-participant” who would be chosen to fly into space as a shuttle crew member, with the clear aim of building public support for space program funding. President Reagan was credited with insisting that the first “ordinary person” selected for space be a teacher (Magnuson, 1986a). Christa McAuliffe became “the national focus of the last Challenger mission— the apple-cheeked schoolteacher who was going to teach a lesson from space. If people cannot remember any other name from the crew, they do remember hers” (Cobb, 1996, p. 1). She was called “a public relations natural” (Magnuson, 1986a), and, indeed, media attention to the flight was greatly increased. Over 800 reporters, five times the usual number, were at the Kennedy Space Center on launch day. That number increased to 1,200 within hours after the explosion (Murphy, 1986a).

The rest of the crew became much more widely known from media coverage following the explosion. The seven-person crew was shown to be made up of broadly talented, dedicated professionals, six married, five with children, who had a love of science and space exploration. The crew was seen as “good people” whose untimely death was especially unjust (Goleman, 1986). The racial and gender diversity of the Mission 51-L crew offered role models for almost every group in America.

Multiple Group Ownership of the Challenger Mission and Crew The popularity of the crew and the awareness and interest of the public, all fueled by broad media coverage following the explosion, resulted in many groups feeling that they were actively involved in the mission, the crew, and their destruction. The interest of no group was more frequently recognized than American schoolchildren. Both Reagan and Bush had directed comments to America’s schoolchildren in their initial addresses to the nation. Part of the success of the Teacher-in-Space Program was in eliciting youth participation and enthusiasm about the mission. This was the “schoolchildren’s shuttle.” Science classrooms across the country were provided with special teaching plans related to Mission 51-L in preparation for Christa McAuliffe’s two live broadcasts from space, which were to be carried by the educational broadcasting system (Wald, 1986a).

Millions of schoolchildren were witnesses to the explosion. Later studies showed that most children experienced “substantial emotional distress” following the loss of Challenger. A New York Times/CBS News Poll of over 200 children, ages 9–17, 2–3 days after the accident found 52% of teens and 30% of late elementary schoolchildren reporting being upset “a lot” by the accident. The majority of students in both groups reported knowing that a teacher was on board Mission 51-L, and the majority felt that the teacher was much like their own. A smaller majority reported that their school had discussed the accident in class (Clymer, 1986). As for older students, a study on the impact of the explosion on college students conducted soon after the disaster revealed that the Challenger explosion was named as the “most shocking” major news story in their lives. Seventy-eight percent of those interviewed reported “strong” or “very strong” emotional reaction to the tragedy; almost 90% predicted that they would never forget where they were when they heard about it (Kubey & Peluso, 1990). Follow-up studies over a year later revealed that the memories of the event were still clear in the minds of both young and older students (Terr et al., 1996). The majority of students interviewed could recall where they were and how they came to learn about the explosion. However, almost a third of those students interviewed had retained false details based on initial misconceptions about the event.

The emotional impact of the crew death was magnified for students of all ages by McAuliffe’s presence. Said one teacher finalist, “A teacher in space becomes your teacher. Do you know an astronaut? Everyone knows a teacher” (Magnuson, 1986a, p. 30). But it seemed that groups everywhere knew someone on the crew. Hometowns, home states, high schools, undergraduate and graduate schools, times seven, could and did claim strong connection to the “heroes” of Mission 51-L. More so than at the time of the Kennedy assassination, a diverse array of survivor groups mourned the loss of “their” astronaut. Moreover, that loss was uncontaminated by the feelings of revenge that may accompany a terrorist act or any divisions of race, religion, nationality, or political beliefs, as have followed other U.S. disasters and tragedies (Morrow, 1986).

A “shared sense of mourning” was the situation described in many news articles in the days following the explosion, and this communality was significantly enhanced by the media. The New York Times devoted an unprecedented 10 full pages, including the entire front page, to the disaster. The Miami Herald produced a special 8-page section that needed to be added to the already printed daily edition of January 28th. All 67,000 copies of an extra edition of Denver’s Rocky Mountain News sold out; no other extra edition had been printed by the Rocky Mountain News since V-J day, more than 4 decades before (Murphy, 1986a).

But it was television that would provide the most vivid coverage of the explosion and the impact of the loss by showing the faces of those who witnessed it. A survey conducted by the National Science Foundation determined that 95% of Americans had viewed some of the Challenger explosion coverage by the end of the day of the loss (cited in Wright et al., 1989). All three network channels were on-air with coverage within 6 minutes of the explosion, and they provided continuous reporting for more than 5 hours. Each offered special evening broadcasts. The blow-up of the Challenger was repeated hundreds of times, in regular speed, slow motion, and stop action. ABC’s news anchor, Peter Jennings, recalled, “We all shared in this experience in an instantaneous way because of television. I can’t recall any time or crisis in history when television has had such an impact” (Murphy, 1986a, p. 42). Jennings received over 10,000 letters thanking him for his coverage during such a difficult time (Kaye, 1989). The role television played in both intensifying reactions to the disaster and in providing a surrogate grief processing group has been the topic of discussion of mass communication professionals (see Kubey & Peluso, 1990). It is clear that television furnished the American public with pictures of the loss itself, cues to emotional reactions and interpretation of the event through interviews and commentaries, and front-row seats to memorial ceremonies and investigative hearings—all “up front and personal.”

The Survivor Groups

The idea of group survivorship permits the examination of the impact of a death on aggregates of individuals beyond the family and friends of the deceased and promotes the explorations of ways to help groups respond positively to the death. A positive response would be one that assists members in acknowledging the loss as a group and serves to facilitate adjustment to the loss. A model outlining rights and obligations of survivor groups will be described in greater detail later in the chapter. But even a cursory review of the events that took place following the Challenger disaster reveals that many groups, from the United States as a nation to the crew members’ families as a unit, were identified and identified themselves as distinct aggregations of people uniquely touched by the loss of Challenger. That so many groups would want to claim a connection to the disaster is not surprising in light of the high profile of the event that resonated so much with America’s image of itself and its history. Moreover, President Reagan provided an immediate and powerful guide at the national level that could be readily copied by those community and state leaders who wished to express their special connection to individual astronauts.

Following the death of a member within a typical organization, such as a school or business, some group members or classes, departments, or sections of the organization will be more directly affected by the member’s death than others. The degree of connectedness of a particular group or subgroup to a crisis often determines the need for group response or the consequence for group members if such commemorative responses are not undertaken. This is the idea and impetus of the concept of levels of survivorship (Zinner, 1985).

At the primary level of survivorship are the family members and intimates of the deceased. But anyone who identifies strongly with the deceased may experience the grief ordinarily ascribed to family members. Secondary-level survivors are those individuals who have intermediate-level knowledge and interaction with the deceased through work or neighborhood association. Friends and acquaintances might readily be considered secondary-level survivors. Their grief level might be anticipated to be more moderate than that of primary survivors, but there may be some expectation of their taking part in postdeath ceremonies or, at least, directly contacting family members of the deceased.

Tertiary survivors are those who share a significant social characteristic with the deceased, such as occupational or recreational activity or geographic or ethnic identity, but who may have had little or no interaction with the deceased. These “socially ascribed” survivors may experience strong but relatively temporary feelings of loss because someone “like” them has died. Finally, quartenary or fourth-level survivors are those individuals who share one particularly broad and general characteristic, again, such as geographic or ethnic identification. Such groups of survivors may or may not feel connected to the deceased and may or may not be or wish to be incorporated into postloss activities.

Identification of specific survivor groups and their degree of connectedness to the loss of Challenger is a complex undertaking given the number and size of so many self-identified groups and the high emotional involvement of so many of their members. The cultural nodality of the explosion, no doubt, also impelled some groups to want to be associated with this historic event. The following groups and subgroups may be seen as survivor groups spanning all levels of survivorship.

Next-of-Kin Over time, the private grief of family members became the subject of numerous newspaper and magazine articles (Dowling, 1996; Swarns, 1996). Although crew spouses continued to be publicly supportive of NASA, and all families were represented on the board of the Challenger Centers for Space Education, family members reported the continued difficulty they experienced with the repeated showings of the Challenger explosion. Pilot Michael Smith’s younger brother explained, “On any given moment, on any given day, I can turn on the television and see my bother and the shuttle crew die.” The frequent ceremonies held in honor of crew members brought mixed feelings to some. “Every new year brings another anniversary of the disaster, another flurry of publicity and another wave of what [Gregory] Jarvis’ stepmother, Ellen, describes as ‘dreadful, shattering pain’” (Swarns, 1996) (p. 21). In Beaufort, North Carolina, the Michael Smith family requested that the annual ceremony honoring their son be called off. In this instance, at least, a conflict seemed to have developed between the larger social group’s need to identify with the loss of a heroic member and the family’s need to put the public aspects of the event behind them.

NASA At first, NASA received many expressions of sympathy from outsiders who recognized the personal and professional effort represented by the shuttle and the impact of the loss on the organization. NASA, second only to the families in level of intimacy with the crew, was mourning the loss of its own. But the Rogers Commission blamed NASA and its management style for allowing what the Commission saw as an avoidable accident. The strong conflict of feelings among NASA employees and between subgroups within NASA became known through news articles and interviews. “‘There’s more outrage here than in the public because of what might have been seen but not acted on,’ one unidentified source close to the Johnson Space Center in Houston was quoted as saying a month after the accident” (Martz, 1986, p. 19). Although both the Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral held private ceremonies following the explosion and both continue to carry out annual rituals in memory of the crew and mission, NASA itself was on trial during the Commission hearings, and this fact, along with the complex bureaucractic divisions and multigeographic locations, could be expected to complicate the grief process of the organization and its employees.

In addition to NASA, other groups closely associated with the space program and with the shuttle missions, such as the private contracting companies, tended to see themselves as survivor groups as well. Also affected were the communities of Florida’s Space Coast, such as Titusville, Cocoa, Rockledge, and Palm Bay, towns in which space talk is common, and every fast-food restaurant displays shuttle pictures.

Concord The town of Concord, New Hampshire, the smallest state capitol in the nation and the home of Christa McAuliffe, clearly identified itself as a “close” survivor group. When she was alive, the city newspaper, the Monitor, called McAuliffe “this city’s shining example” (Wald, 1986c, p. 17). She was asked to serve as grand marshall in Concord’s 1986 New Year’s Day parade. It was the town’s big send-off for its most famous citizen. After the disaster, the editor of the Monitor, Mike Pride, wrote a piece for Newsweek magazine (Pride, 1986) which he entitled, “There had been a death in the family.” He described his joy and civic pride when the crew member to represent the Teacher-in-Space Program had been selected from his home town. He wrote that “Christa made Concord proud. The people in our city saw in her the best that we have to offer” (Pride, 1986, p. 42). Said the Rev. Daniel Messier, at a Catholic service for McAuliffe the morning following the explosion: “She was Concord. When she stepped on that shuttle, Concord stepped on that shuttle” (Wald, 1986b).

All of Concord—McAuliffe’s students, her fellow teachers, her neighbors, and members of her church—took her death quite hard. Newspaper articles described a town that had closed ranks against outside reporters and any interference with the McAuliffe family’s privacy. “The state memorialized McAuliffe by building a planetarium and space museum. But many locals say they’ve never been there. Some say they prefer to remember McAuliffe as a friend or a teacher, not as a subject of media hoopla” (Larrabee, 1996). Ten years later, no streets have been renamed in her honor and no plaques honoring McAuliffe hang in Concord city buildings (Larrabee, 1996).

Other Survivor Groups Other identifiable groups of individuals who could be seen as connected to the loss of the shuttle were American schoolchildren; primary and secondary school teachers, especially science teachers; the hometown and universities of all of the astronauts; and the United States as a nation. Whether any or all of these groups responded positively as a survivor group depended greatly on whether group leaders existed and acted in a way that clearly identified the link between the group and Mission 51-L. The largest of the survivor groups mentioned, the United States, benefited from the leadership provided by President Reagan in his two public addresses. In his speeches on the afternoon of the explosion and at the national memorial service on the following Friday, Reagan acted as “chief national mourner” (Adler, 1986, p. 26). He offered words of consolation to family members both privately and publicly. He invoked the image of pioneers in describing the bravery and courage of the astronauts. He pledged to continue their “dream” and to continue the idea of “ordinary citizens” being a part of the manned space program. In doing so, he provided affirmation of the shared pain and offered direction for finding meaning in the loss. Reagan was acknowledged as a “healer” in the media (Apple, 1986).

A Model of Group Survivorship

Postdeath rituals focused on the next-of-kin serve many purposes. Primary aims of such rituals are the necessary disposal of the body in a culturally prescribed manner designed to show respect for the body, affirmation of the loss and the subsequent pain for the survivors, and, often, a community-focused expression of support for the bereaved. Postdeath rituals also provide direction for immediate and longer term behavior of family survivors. Condolence rituals, such as the sending of flowers and sympathy notes and the printing of obituaries, often acknowledge the significance of the deceased to the family and community in general and offer salutary explanations of the meaning of life and death. In sum, postdeath rituals are designed to propel and facilitate the bereavement process. The structure of culturally sanctioned postdeath rituals is fairly universal because the need for the family to grieve and to adjust is universal following the loss of a member.

Bereaved groups of individuals, beyond the family unit, often have a similar need for directed response and adjustment when the group organization is disrupted by the loss of a significant member. Unfortunately, norms for group survivorship are not as culturally established, nor are their purpose as intentionally described. But not to consider and encourage a response from a group following the death of a member is to give a public indication of the minor impact of the loss and, by extension, the minimal worth of the absent member or of any other member.

An articulated model of group survivorship would serve as a sensitizing paradigm to alert group members, particularly group leaders, to those actions and needs that would facilitate group adjustment in times of significant loss. It could also guide policy planning for organizations such as schools, where deaths of group members must be anticipated and planned for, given the unfortunate frequency of their occurrence. Such a model, too, would be useful in assessing the appropriateness and completeness of those actions that are taken following a group loss so as to better prepare for any future circumstances.

One theoretical model of group survivorship, described by Zinner (1985), proposes that survivor groups have certain social rights and obligations, analogous to those afforded family survivors. While groups differ in size and cohesiveness and even in awareness of their being (e.g., a temporary grouping of football fans at a stadium), recognition of the rights and obligations of members who experience a crisis as a group is hypothesized to facilitate the immediate, as well as long-term, well-being of all those associated with the loss. Conversely, if no coordinated response to a member’s death is forthcoming, the lack of group response suggests a lack of leadership or awareness of group needs— a common occurrence in this society.

Social Rights (SR) of Survivor Groups A survivor group can be seen as having certain social rights conferred on it, ideally, by those outside the group.

(SR/1) The first right is to be acknowledged and recognized as a survivor, as having suffered a significant loss. When outsiders react to group members as a group that has endured a loss through a member’s death, it serves as public affirmation that the deceased was not just any isolated individual but, indeed, a member of that group. Following the explosion of Challenger, social condolences were directed to a number of survivor groups. Certainly, spouses and parents of the crew received many expressions of concern and sympathy, but social condolences were also clearly bestowed upon the United States, NASA, Concord High School, and the town of Concord. These groups were perceived as secondary-level survivor groups or perhaps as symbolic secondary-level survivors in the case of the American nation. Others saw these groups as being especially distressed by the crew loss and responded accordingly. This right did not appear to be extended to other communities or universities historically associated with the crew.

(SR/2) A survivor group has the right to be informed of facts concerning the death and subsequent actions taken. This claim is fairly obvious and presupposed in the instance of family survivors. When a family member dies, close relatives expect to be fully informed as to the cause of death and to be permitted to participate in any postdeath ritual. Not to be so treated would be a breach of cultural expectations and would be received with bewilderment and anger in most cases. In instances of terrorist acts, this may create conflict when issues related to national security prevent full disclosure to relatives of the deceased. Indeed, one of the earliest issues typically addressed by survivors is the question of how and why a death took place.

Initially, NASA approached the issue of the cause of the Challenger explosion with much public reticence, refusing during the first few days following the explosion even to release information on the temperature at the launch pad (Marbach, 1986b). Within the first week of the investigation, The New York Times had disclosed internal NASA documents that had warned about problems with the O-rings of the solid rocket boosters. After only 7 days of hearings before the Roger Commission, evidence emerged that pointed to problems in the O-ring of the right solid rocket booster. But NASA publicly ignored leaks to the press about its prior knowledge of such problems and the evidence that was mounting before the Commission. Commission Chair Rogers found sufficient NASA dereliction in the decision-making process for him to excuse all NASA officials involved in the mission launch from participating in the investigation (Murphy, 1986b)

Over the months of the Commission’s investigation, no NASA employee who appeared before the Rogers Commission conceded that he would have altered his decision to launch, given the same set of circumstances (Magnuson, 1986c). Lawrence Mulloy, manager of the solid rocket booster project and seen by many as bearing a significant amount of responsibility for the accident, had been alerted the night before the launch of serious reservations on the part of Morton Thiokol engineers who only reluctantly signed off on the go-ahead for launch. Before the Commission, Mulloy stated, “I regret the accident, but I don’t feel guilty about it. In hindsight, it was a very bad decision to launch. Wish we hadn’t done that. But … given the same data, given the same history and following the same rules, one would have to make the same decision again” (Burkey, 1997, p. 2). Mulloy maintained that everyone, from astronauts to top managers, was aware of the problems related to the O-rings; all had accepted what would be considered a calculated risk.

Where an apology can do little in reality to make up for a disaster, the lack of an apology will outrage those most affected by a tragedy. Even the corps of astronauts, a survivor group about which little was written following the disaster, expressed disillusionment and anger. John Young, chief astronaut, sent a strongly worded letter berating NASA for allowing internal and external pressures to lower safety standards, putting the ship and lives at serious risk (Marbach, 1986a). Christa McAuliffe’s mother remembered her husband being most upset because “no one ever said they were sorry” (Cobb, 1996, p. 1).

NASA’s reputation was further damaged by revelations that Rockwell International also had objected to the Challenger launch because of the presence of ice on the launch pad structure. Their reservations were also ignored by NASA officials although, in fact, the ice proved not to be contributory to the accident (Magnuson, 1986c). Public confidence in NASA in 1986 was further eroded when, in April, a Titan 34-D rocket carrying a military reconnaissance satellite for an Air Force mission not related to NASA and, in May, a Delta 3920 rocket carrying a weather satellite, both exploded soon after launching (Lewis, 1988). The Delta rocket was struck by lightning and destroyed by NASA seconds after being launched during a severe rain storm. It would be almost 3 years before the shuttle program would resume flights.

A second issue of fact that proved troublesome to the public had to do with the timing and cause of the crew members’ deaths. From the beginning, NASA had maintained that the crew had died instantly in the explosion. Given a projected force of 20-Gs occurring when the cockpit section separated from the orbiter after the explosion, it does seem unlikely that anyone would be conscious after experiencing this type of shock. What is more, the cockpit section continued upward to an altitude of 80,000 feet after separation, and the cabin would have experienced explosive decompression that would have proved lethal to the crew members who were not wearing pressure suits.

Still, NASA was not to be believed on this point by many Americans. This alleged deception is explained by some to not only have been undertaken to protect the feelings of next-of-kin but also as a political maneuver to keep the public from learning that the crew most probably survived the explosion only to die in the subsequent fall of the shuttle into the ocean. Several news agencies sued in court, under The Freedom of Information Act, for access to the tape recordings of cabin conversation in order to verify the transcript released by NASA. A federal appeals court sided with NASA’s contention that voice records would be a serious invasion of the privacy of the families (“Challenger: The final words,” 1990). When the crew compartment was discovered within a month of the disaster, NASA would not confirm or deny the find (Magnuson, 1986b).

Eventually, a NASA official did report to the Rogers Commission that the “crew survived the fireball and the breakup of the orbiter and perished of either decompression shortly thereafter or impact with the water” (Lewis, 1988, p. 175). Three of the four individual crew member air packs found in the recovery effort had been manually turned on. But because of extensive damage to the bodies of the crew members, the cause of death could not be determined. No discussion appears in the Commission report on the bodies of the astronauts and no forensic evidence was ever given to the public. Even the request from the Journal of the American Medical Association to examine the autopsy report was denied by NASA, which cited Exemption 6 of the 1977 Freedom of Information Act, a clause permitting government agencies to withhold information which would represent an unnecessary invasion of privacy (Lewis, 1988). Whether the pubic had a “right” to know the disturbing details of the crew’s deaths is reasonably debatable; that the public wanted to have full knowledge of the details in order to comprehend fully what had occurred is clear. The review of the Challenger tragedy shows that it is this aspect of this particular model of group survivorship that appears most seriously violated.

(SR/3) A final right of a survivor group is to be allowed to participate in traditional or in creative leave-taking ceremonies. Funeral rites exist universally to give direction to the bereaved in their efforts to acknowledge and cope with loss. In western society, many occupational groups who experience high mortality rates (such as law enforcement agencies, fire departments, military organizations) and male-dominated groups in general (such as adult fraternal organizations and sports associations) have developed traditional observances which are carried out when a member dies. Funeral rituals that are either attended by a survivor group or its representatives or created by and for the survivor group offer confirmation of the group’s association with the deceased and an opportunity for surviving group members to “pay their respects.”

Live television coverage of the memorial services on Friday, January 31, provided an opportunity for Americans to attend the national tribute to the astronauts and mission payload specialists of the shuttle Challenger. With the President at the podium, all Americans were duly represented. Group survivors from NASA, from Concord, from Concord High School, and from the crew’s home states and universities all were able to be a part of commemorative efforts that spoke of both the courage of the crew members and the relationship of each of these survivor groups with Mission 51-L.

Social Obligations (SO) of Survivor Groups While survivor groups may be afforded certain social rights by those outside the group in recognition of their bereavement status, survivor groups are also required to respond in particular ways. Thus, specific social obligations coexist with the social rights previously described.

(SO/1) An important social obligation is for the group to acknowledge publicly the group’s survivorship status. Without an outward display to indicate that a loss has occurred, others cannot know or respond to a group’s loss. On an individual level, the American society has abandoned many of its earlier symbols of bereavement such as the draping of a home with black materials or the wearing of a black arm band or widow’s weeds. However, it is not uncommon to find a sports team wearing black arm bands, or a police station flying a flag at half-mast, or high school students tying ribbons to a tree in recognition of another student’s death. These actions alert all who see them that the group has suffered a significant hurt. Indeed, when no externally directed action is taken by a group or subgroup within a larger organization, a business-as-usual impression is created which is increasingly perceived as heartless as opposed to stoic.

Almost all of the survivor groups previously discussed in relation to the Challenger explosion reacted in a manner that alerted others (and their own members as well) that they had been directly affected by the death of Challenger’s crew members. There are two notable exceptions. One is the group composed of American schoolchildren. This group might be seen at first to be merely an aggregation of individuals based on a given age range and occupational similarity of sorts. An organized response perhaps could not really be expected. But an organized response was created on behalf of the American people. Flags were lowered at all government buildings; national memorial services were arranged; a national marker was erected at Arlington Cemetery. NASA did receive small donations of money from many schoolchildren who hoped to contribute to the rebuilding of the shuttle (Magnuson, 1986a). The difference between the survivor group of American children and the survivor group of the America people was one of leadership. There was no leadership structure in place or assumed (for example, by a national council of PTAs, scouting organizations, or even a fast-food chain) which might have served to guide a response symbolizing the impact of Christa McAuliffe’s death, in particular, on school-aged children. Students across the country might have been encouraged to wear an apple-red ribbon on the day of the Friday national service or to have “their” representative speak at the service itself or to have the front doors of all primary and secondary schools trimmed in some appropriate manner by student leaders; but none of these was done.

The other group which did not outwardly identify itself as a survivor group was the corps of astronauts who may well be considered a near primary-level survivor group, both in their personal association with the astronauts and payload specialists who died and in their identification of the tragedy with their own professional role. It may be that, like the family members of the crew, their group behavior and personal grief was kept as private as possible. There was little mention of the astronaut corps in the public documents examined for this chapter.

(SO/2) A second obligation connected to a survivor group is to make a tangible response to the defined immediate/family survivors on behalf of the group. It is assumed that the next-of-kin are most bereft following a death and are in most need of consolation. A show of support of the family through the sending of sympathy cards, attendance at the funeral, or the establishing of memorials to the deceased by the group and/or its representatives is a traditional mechanism used by groups to pay due respect to the next-of-kin and to show attachment. Clearly, family members were recognized by many in an outpouring of written words of sympathy received by all families of the Challenger crew, both from individual Americans and from recognized groups.

An obstacle to adequately meeting this social obligation arises frequently when group leaders express their commiseration to family members on behalf of the group but overlook the need to inform their own group members of such actions. Any action taken in the name of a survivor group which is generally unknown to group members does not serve the bereavement needs of the whole.

(SO/3) Finally, a survivor group is obliged to make a tangible response within the group to benefit group members. The deceased member is known to the group in ways distinct from how the family or other associated groups know the deceased. Group-centered ceremonies or memorials can be created in a way that honors this idiosyncratic relationship and that simultaneously reflects the special attributes, goals, or achievements of the group. Typical in our culture is the naming of a government building after an influential leader or creating a memorial playground in honor of a student who has died. These are ways in which members of an affiliated group can signify their special remembrance of a member. Often, these unique commemorations also provide a way of formulating a meaningful interpretation of the loss.

The founding of Challenger Centers for Space Science Education by the families of the Mission 51-L crew not only provided an educational benefit to schoolchildren but, just as importantly, created a living tribute which could give purpose and meaning to the loss of the crew. So, too, special projects and memorials established by NASA via the Astronaut Memorial Foundation, by the National Education Association, and by the state of New Hampshire, to name a few, lent poignant expression to the examination of the meaning of the Challenger tragedy.

It is an interesting exercise to research and write about the Challenger explosion and its aftermath given that I, too, am a group survivor, an American who witnessed the events being described. Friends and colleagues who were aware of my professional interest in constructing this piece seemed compelled to tell me where they were when they first heard about the accident. And I felt the same compulsion to confess that I had been sequestered that momentous day, assisting in a neuropsychological assessment of a sailor at the Portsmouth Naval Base, and felt as if the world had somehow changed when I learned, hours later, that the Challenger and its crew had been lost. My interest in the issues of supporting bereaved groups of individuals preceded the tragedy but was always somewhat influenced by it.

The academic and clinical fields of grief and bereavement and of trauma are only now coming together after years of investigation in both areas. The Challenger disaster serves as but one broad example of how the deaths of individuals can affect the identity and emotions of organized groups of people. The Challenger explosion stands out in American history as an event that captured the attention and heart of a diverse number of groups. Clearly, the conduct of many of Challenger’s survivor groups met the social rights and obligations noted by the model of group survivorship that was presented. Whether actions taken on behalf of these groups over the intervening 10 years successfully met the needs of their many members is not answerable based on public documents. But observing the model applied, even in a particularly broad-scale instance, may assist intervenors and group leaders in directing responses in new situations of group loss and in evaluating the efficacy of those responses.

“The Shuttle Explodes,” ran the banner headline of The New York Times on January 28, 1986. Clearly, the images of that explosion endure in the American psyche a decade later.

Adler, J. (1986, February 10). We mourn seven heroes. Newsweek, 26.

Apple, R. W., Jr. (1986, January 29). President as healer. The New York Times, p. A7.

Boyd, G. M. (1986, January 29). Bush offers his solace and urges nation to ‘press on’ with exploration of space. The New York Times, p. A9.

Broad, W. J. (1986, January 27). Shuttle launching delayed again over weather fears. The New York Times, p. A14.

Burkey, M. (1997, June 10). “I was playing by the rules.” [On-line]. Available: http://www.htimes.com/today/Challenger/part2.htlm

Challenger: The final words. (1990, December 24). Time, 15.

Christa McAuliffe remembered by hometown. (1996). Associated Press [On-line]. Remembering Challenger Index. Available: http://www.infoseek.com

Christa McAuliffe’s mom speaks out on Challenger disaster to Prodigy members. (1996, January 26). Prodigy Services Company [On-line]. Available: http://pages.prodigy.com:8987/mservice/pn012696.xbm

Clinton remembers ‘explorers’ of Challenger crew. (1996, January 27). Nando.Net [On-line].Available: http://www.nando.net/newsroom/netn/nation/012796/national12-24463.html

Clymer, A. (1986, February 2). Poll finds children still enthusiastic about space. The New York Times, pp. A1, A16.

Cobb, K. (1996, January 27). Challenger families wrestled with loss shared by the world. Houston Chronicle, p. 1ff.

Cook, W. J. (1996, January 29). Shuttling cautiously ahead, 10 years later. U.S. News & World Report, 11.

Dowling, C. G. (1996, February). Ten years ago seven brave Americans died as they reached for the stars. Life, 38–40, 42–43.

Eberhard, J. (1994, January). Challenger Point, 14080', memorial plaque [On-line]. Trip report. Newsgroups: rec.aviation.stories, rec.aviation.misc.

Goleman, D. (1986, February 1). Anger, confusion, and fear in the nation’s grief. The New York Times, p. A11.

Kaye, E. (1989, September). Peter Jennings. Esquire, 158–176.

Kubey, R. W., & Peluso, T. (1990). Emotional response as a cause of interpersonal news diffusion: The case of the space shuttle tragedy. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 34(1). 69–76.

Larrabee, J. (1996, January 26). For New Hampshire students, a difficult memory. USA Today, p. 3A.

Lewis, R. S. (1988). Challenger: The final voyage. New York: Columbia University Press.

Magnuson, E. (1986a, February 10). They slipped the surly bonds of earth to touch the face of God. Time, 24–31.

Magnuson, E. (1986b, February 17). A cold soak, a plume, a fireball. Time, 25.

Magnuson, E. (1986c, March 10). A serious deficiency. Time, pp. 38–39, 42.

Marbach, W. D. (1986a, March 24). No cheers for NASA. Newsweek, 18–19.

Marbach, W. D. (1986b, February 24). Closing in on calamity. Newsweek, 58–59.

Martz, L. (1986, March 3). Days of decision: A countdown. Newsweek, 16–19.

Media coverage of Challenger 10th observance. (1996, January 23). Challenger Learning Centre [on-line]. Available: http://www.osc.on.ca

Morrow, L. (1986, February 10). A nation mourns. Time, 22–23.

Murphy, J. (1986a, February 10). Covering the awful unexpected. Time, 42–43.

Murphy, J. (1986b, February 24). Zeroing in on the O rings. Time, 58.

President expresses his sorrow at the astronauts’ deaths. (1986, February 29). The New York Times, p. A9.

President’s letter to Concord High School. (1986, February 1). The New York Times, p. A11.

Pride, M. (1986, February 10). There had been a death in the family. Newsweek, 42.

Rimer, S. (1986, January 29). After the shock, a need to share grief and loss. The New York Times, pp. A1, A3.

Schmemann, S. (1986, February 2). Soviet Union to name 2 Venus craters for shuttle’s women.The New York Times, p. A16.

Schmidt, W. E. (1986, February 2). Memorial wreath dropped into the sea. The New York Times, p. A16.

Schwartz, H. S. (1987, Spring). On the psychodynamics of organization disaster: The case of the space shuttle Challenger. Columbia Journal of World Business, 59–67.

Swarns, R. L. (1996, January 28). Challenger disaster 10-year anniversary. The New York Times, p. 21.

Terr, L. C., Bloch, D. A., Michel, B. A., Shi, H., Reinhardt, S. A., & Metayer, S. (1996).Children’s memories in the wake of Challenger. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(5), 618–625.

Their families today. (1996, January). Houston Chronicle [On-line]. Available: http://www.chron.com/ content/interactive/special/Challenger

Transcript of the President’s eulogy for the seven Challenger astronauts. (1986, February 1). The New York Times, p. A11.

Wainwright, L. (1986, March). After 25 years, an end to innocence. Life, 15ff.

Wald, M. L. (1986a, January 29). Cheers turn to numbness as Concord High School mourns one of its own. The New York Times, p. A3.

Wald, M. L. (1986b, January 29). In Concord, McAuliffe’s neighbors mourn loss of a ‘shining example.’ The New York Times, p. A17.

Wald, M. L. (1986c, January 31). A day of grief and praise for McAuliffe. The New York Times, p. A15.

Weintraub, B. (1986, February 1). Reagan pays tribute to ‘our 7 Challenger heroes.’ The New York Times, pp. A1, A11.

We remember. (1996). Houston Chronicle Interactive [On-line]. Available: http:www.chron.com/ content/interactive/special/Challenger/response/response.html

Wolfe, T. (1986, February 10). Everyman vs. Astropower. Newsweek, 40–41.

Wright, J. C., Kunkel, D., Pinon, M., & Huston, A. C. (1989). How children reacted to televised coverage of the space shuttle disaster. Journal of Communication, 39(2), 27–45.

Zinner, E. S. (1985). Group survivorship: A model and case study application. In E. S. Zinner (Ed.), Coping with death on campus (pp. 51–68). New Directions for Student Services, No. 31. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.