CHAPTER 5

Defusing Conflict and Overcoming Roadblocks

Why is the potential for conflict in the virtual world so great? The lack of structure compared with the traditional workplace creates many more opportunities for misunderstandings, inconsistencies, communication barriers, and ways to fly under the radar. Managerial oversight is spread thin, and members from different cultures who may speak other languages work in complex situations. Unfortunately, the conditions for conflict to arise appear all too easily.

Here’s what your peers say about conflict in the virtual world:

“The main source of virtual conflict occurs when people don’t have the same expectations about outcomes or goals. Confusion occurs around who is doing what, who is allocated how many hours, and personality differences.”

—VIRTUAL LEADER, INVESTOR RELATIONS

“The biggest virtual conflict involves communication or lack thereof: How come I wasn’t told? How come no one communicated with me? Other conflicts between virtual team members happen when people don’t pull their weight. Generally, they don’t talk to each other. They go to the project manager, and the project manager has to deal with it.”

—PROJECT MANAGER, PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY

“Since you don’t have body language and eye contact, which are so much a part of how we communicate, verbal or e-mail messages can be easily misinterpreted. There are many more misunderstandings in the virtual environment. For example, e-mail blasts across the organization can be more risky than yelling down the hallway. Conflict can arise from misinterpreting an e-mail sent out of emotion or not fully thought through.”

—FIELD OPERATIONS MANAGER, GOURMET FOOD COMPANY

Are these situations familiar to you? Conflict happens. Regardless of work arrangements, confusion and obstacles are bound to occur. However, by its nature, the virtual environment lends itself more easily to situational conflicts than traditional work arrangements. When colleagues aren’t in close contact they can “hide,” and so conflicts may be overlooked or may lie under the surface for a long period of time before problems are noticed. As a virtual leader, you want to be a little more vigilant about detecting the early warning signs that friction is bubbling up or that a breakdown in communication is imminent.

Conflicts, even minor ones, need to be addressed early or they tend to spiral out of control, especially in the virtual environment. For example, conflicts can arise from simple e-mail miscommunications that turn into challenging situations. In essence, the potential for conflict exists whenever people perceive a concern or preference differently, and each person champions his or her own position.

There are four typical types of virtual conflicts: performance conflict, identity conflict, data conflict, and social conflict.

Performance Conflict: What Am I Supposed to Do and How Should I Do It?

There are many instances in the virtual world that lend themselves to performance conflict. Reasonable people may differ about work-related issues: What tasks need to be performed—and how should they be carried out? What resources are needed to move a project forward? Who needs what from a colleague or team? How do we clarify processes and procedures for those who need to know, but whose language skills make communication difficult? What is the best way to solve problem X? Although unresolved conflicts may lead to lower performance, some conflict can energize performance and actually increase team success (achievement), especially if the issue is quickly resolved.

“There is always some virtual conflict about performance. The greatest conflict comes out of not having a clearly defined mission or purpose, [with] no way to measure the group’s performance or to hold people accountable. And if the manager doesn’t have a strong statement about what the team is set up to do—no clearly defined objectives/deliverables—that’s where conflicts lie.”

—VT LEADER, MEDICAL DEVICES

“The main source of conflict on my teams is the different perspectives and differences in priorities. It occurs all the time, every day. I have 100 people, each wanting something right away. Because they are not aware of each other’s needs and they can’t be told for reasons of confidentiality, it’s very hard. I have to share resources, share ideas, share lessons learned from one country’s program with another, but it’s tough to set priorities, respond quickly, and perform. It’s a lot of pressure.”

—VIRTUAL MANAGER, NGO HUMANITARIAN RELIEF

Identity Conflict: Where Do I Belong?

Virtual team members are often placed in situations in which they report to multiple managers in matrixed organizations. Tension and confusion regarding priorities occur when colleagues switch back and forth between assignments. Many people serve on several project teams simultaneously and may have an identity crisis when they must switch between multiple priorities and projects. Often, virtual members are committed to multiple projects and simultaneously report to both a local on-site manager and a virtual manager, making it difficult to figure out priorities.

“Many people have dual accountability to their local manager and their functional manager and struggle with ways to handle two bosses who may not be in agreement regarding results. The problem isn’t that multiple managers ask the team member to do too many things; it’s that they ask [the team member] to do so many things at the same time. You have to make sure that work efforts aren’t duplicated.”

—VT LEADER, PHARMACEUTICAL FIRM

“Given that virtual teams have many skill sets, you need roles defined for them. In the United States, we defined three roles—team lead, database administrator, and communication specialist—and we understood that this arrangement was based on American experience. We ran into situations where the team in India redefined the role for database administrator—theirs served different projects while ours served one client. Their understanding was, ‘I have fifteen hours/week dedicated to project X and then I focus on other ones.’ So we ran into identity crises problems.”

—MANAGER, TELECOM COMPANY

Data Conflict: What Should I Focus on First?

Since virtual teams rely on technology as a communications vehicle more than their traditional counterparts do, there is a greater potential for information overload with the sheer volume of simultaneous communication that can bombard team members. Conflict occurs because individuals cannot handle so much data at once; they may unintentionally forget or miss important details. Not only does information overload cause stress, but the potential to lose track of certain important details can cause conflict if it results in certain tasks being neglected.

“The biggest problem with getting too much information and, in particular, using e-mails is that they can easily become overwhelming. Although you can set some standards about writing, proofreading, and sending e-mails, it’s easy to go overboard and hit ‘reply all’ or ‘cc:’ everyone. I get over 1,000 e-mails a day, and I must go through them [all] or risk missing important information.”

—VT LEADER, COMPUTER SOFTWARE COMPANY

Not long ago I had the following experience with a coaching engagement for a senior executive at a financial services firm: After several preliminary meetings, we set a time to begin the sessions right after the executive’s planned and much-needed vacation. We met the afternoon of his return, and when I walked into his office he immediately pointed out that his in-box had more than 10,000 messages (apparently, he vacationed at a remote location with limited e-mail access), so there was no way he could take time for our session. The memory is still vivid. When he tried to explain why he wouldn’t, or couldn’t, concentrate on the coaching session, he started crying, literally crying. “How can I get through this mountain of data?” he said. “What should I focus on first? It will take me days to sort through this information and I have meetings to attend and work to do. Even if I work at night, it will take time from my family and personal life.”

Clearly, his emotional state precluded a typical coaching session about leadership style, team dynamics, and other issues that we agreed to address. Instead, we sat at his computer and I helped sort through his in-box. For two hours we looked at messages. E-mails that did not require a response were deleted, simple requests were addressed, and short e-mails were sent to colleagues who wanted updates to explain that they would be forthcoming as soon as possible. We also came up with a better system for incoming e-mails, including organizing messages by subject lines and creating subfolders for lower-priority items.

Here, then, was an example of data conflict. Despite the fact that technology is an essential tool in modern business, it also creates situations where any one of us can swim in a sea of data overload.

Social Conflict: Who Are the People on My Team and What Are Their Personalities?

Social conflict can be defined as personality clashes or the tensions that arise between people because of differing interpersonal styles. Social conflict often arises on a virtual team because members do not have the time or opportunity to create strong relationships with teammates, which tend to minimize the impact of misunderstandings. The flexibility inherent in face-to-face contact, with direct (verbal) and nonverbal communication cues, is missing here, and so an opportunity to understand why people act a certain way is lost.

Instead of giving someone else the benefit of the doubt, we may retreat deeper into our own point of view, because it is easier to ignore or circumvent unpleasant situations. Even if we choose to ignore the conflict (“He’s so far away, I really don’t have to deal with him most of the time”), we tend to harp on negative feelings. Conflict can surface and lead to intense exchanges, but more commonly it is ignored until a flash point causes an explosion. In any case, work product is affected, with potential negative consequences down the road.

“Personality conflicts between people via e-mail can affect the entire team. This happened on my team between two people who were on different continents and interpreted e-mail differently. It was exhausting because they jumped on every word and it became worse because of their philosophical difference. It became a ‘flaming e-mail’ that went back and forth for weeks. Each person misunderstood and misinterpreted the written word. I finally had to jump in and conduct a mediation call.”

—SOFTWARE IPO STRATEGY OFFICER

“When there is no sense of an intact project team or any team camaraderie, it can create a lack of empathy on the virtual team. This sounds touchy-feely, but it’s about being unable to take the other person’s perspective, see their point of view, or even understand why they do what they do, because the social element is missing.”

—CONSULTANT, INTERNATIONAL REDEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION

What Type of Conflict Is It?

A problem that occurs in all teams, and especially in virtual teams, is that members often do not really know the form of conflict with which they are dealing. What may appear to be social conflict is really performance conflict. To clarify misunderstandings early on, you need to be aware of differences and how to overcome conflict roadblocks. Team members need time together and the experience of communicating with each other to develop trust, so they can open up and speak about difficult issues. If not, misunderstandings are more likely to end in conflict about inconsistencies, mismatched wishes, or conflicting desires and disagreements.

Adding the Cultural Factor

Cross-cultural workplace conflicts resemble car crashes. Sometimes they are minor events involving a couple of cars, and sometimes the damage is greater. Conflict situations are hard for all of us. But in the daily rush hours of our lives, when we add cultural differences to the constant traffic of heavy workloads, multiple deadlines, and occasional roadblocks, “crashes” are inevitable.

What happens when employees from different cultures react to conflict situations differently? How do these situations get resolved so that goals are accomplished and long-term working relationships are not negatively impacted?

Several virtual managers I spoke with said that the biggest source of conflict in the virtual environment centered on understanding the meaning of certain phrases. They refer to this type of conflict as “overcoming differences.” In other words, they would walk people through examples, give specific instructions, and still certain phrases were misinterpreted. One virtual leader from a major insurance company described a situation: “I had a half-hour phone conversation with English-speaking colleagues from Asia, but I couldn’t understand them and their accent,” he told me. “The technology we used made it hard to hear [each other]. People weren’t always saying the same thing in the same way, so I always had to clarify: ‘John, did you say A, B, and C?’ He would answer, ‘No, no, B, C, and D.’ I then followed up: ‘So, you said B, C, and D?’ Finally he said, ‘No, no, B, D, and F.’ That’s how I learned to overcome our differences and communicate.”

In addition to language barriers, different cultures handle conflicts in their own way. For example, Asians place a high priority on saving face. Americans value direct communication and there is less reliance on nonverbal behavior. When team members are from different cultures, there is, then, a potential for greater conflict, and managers need to know how to handle the situation. These cross-cultural factors/elements are explored further in Chapter 7, but for now this chapter focuses on overcoming obstacles in the virtual environment, regardless of whatever cultural misunderstandings might occur. Figure 5-1 summarizes the main conflict types and how to recognize them.

Figure 5-1. Questions to consider concerning conflict types.

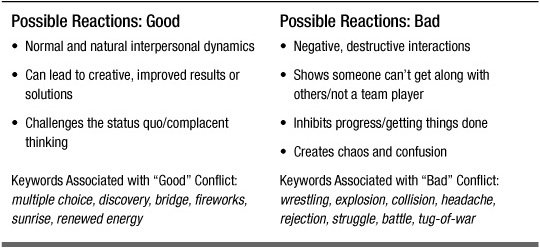

Reacting to Conflict

During many workshop presentations I have given over the years, I would post a picture of a man and a woman seated at a table, facing each other, right hands clasped in an arm-wrestling posture. Then I would ask participants, “What is your reaction to this picture? Is it good or bad conflict?” Invariably I would get a mixed reaction. Some participants viewed conflict in a positive light because they saw two individuals playfully engaged in a tug-of-war, while others viewed it more negatively, seeing a struggle. These common reactions are outlined in Figure 5-2. The point I made was that conflict is not good or bad; it’s how you approach it that matters.

Then I would explore the real question: Why is it important to deal with and manage conflict?

Figure 5-2. Common reactions to conflict situations.

What is your reaction to conflict? Is it good or bad conflict?

Differences in opinions are common among teammates, friends, family members, organizations, and people, in general. Some level of disagreement is healthy because it can generate ideas and build innovation. When everyone always agrees, it is difficult to come up with creative solutions. Many times conflicts result from simple mismatches in perception. These misunderstandings can contribute to more serious conflict issues around speed, results, or personalities, and they may have reverberations that are felt beyond the immediate department or work unit. When stress levels are high (as they often are in the virtual environment), conflicts are more likely to arise. Sudden changes in organizational policy or company direction can cause confusion and lead to conflict. A quick e-mail can spark conflict, as can a casual comment or suggestion during a telephone conference. Virtual team members often feel indifferent toward each other unless they previously took the time to explore commonalities, beginning the process of team bonding. That is why I highly recommend conducting a Team Setup session early in the team’s life cycle. Often the common bonds formed in those early days help to defuse conflict situations later on.

Common reactions to conflict include feelings of betrayal and missed expectations or a simple avoidance of dealing with the issue—any of which may lead to decreased productivity. Virtual employees might avoid a conflict because they do not know how to constructively handle it or they may be afraid of what confronting conflict would do to their reputation. While conflict avoidance seems the easier choice, I’ve seen many negative consequences in the long term when that happens. Sometimes employees become disengaged and don’t speak up, or they wait until things escalate to the boiling point. Subtle examples of conflict avoidance include hitting the mute button and multitasking while on a conference call; not paying attention when a question is asked; and, finally, total disengagement. These actions often result in loss of work quality and indifference; however, the greatest cost is the human cost. Morale and energy suffer because employees are angry and frustrated. Some people may internalize what they hear and start backbiting or plotting to “one-up” another person. What started as a molehill can become an overwhelming mountain.

How can you prevent paying the huge price of conflict and instead reap the benefits of a productive work environment in which teammates work effectively with each other? The first step is to lower barriers to communication and motivation by learning how to handle conflict reactions and turn conflicts into problem-solving opportunities. This chapter includes several tips for resolving conflicts, particularly those common to the virtual environment. First, though, let’s focus on the productive and destructive dimensions of conflict, levels of conflict, aspects of conflict, and explore a real-life case study that combines all these elements.

Dimensions of Conflict

Although the word conflict tends to connote something negative, it does not necessarily have to be destructive. Conflict situations, when appropriately handled, can yield productive results. If virtual teammates can recognize and defuse potential conflict situations before harm is caused, they provide growth opportunities. Figure 5-3 gives examples of the productive and destructive characteristics of conflict.

Figure 5-3. Productive and destructive characteristics of conflict.

Levels of Conflict

According to Richard De George’s Ethical Displacement Theory, there are three levels to conflict: interpersonal, organizational, and societal/cultural.*

Some conflict dilemmas must be resolved at a level other than the level at which they are manifested. For example, an interpersonal conflict between an employee and his or her manager (e.g., a disagreement over a performance appraisal) may need to be handled at the organizational level (in this case by company policy) or across physical boundaries.

*De George, Richard, Business Ethics, 7th ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2009).

Here’s a quick scenario based on an actual conflict situation that I was called in to help resolve. After reading the case study, please reflect on how you would act in a similar situation. Later on in this chapter, I’ll offer specific tips and steps for handling conflict and undertaking mediation.

CASE STUDY

Hurt Feelings Lead to Hurting the Business

William, the vice president of accounting for his division, works at corporate headquarters in London and has a dotted-line responsibility for a global accounting team that spans three other locations—Cape Town, Seoul, and Houston. He has committed this team to standardizing all financial reporting for the division because sales and marketing could no longer project inventory accurately using an “apples and oranges” approach to global customers. The target date for replacing the old system was the end of the current fiscal year, and until that time, all centers would have to run dual systems. Although the company was based in London (mainly because its founder was British), by far the largest operation was in Houston. Leo, Houston’s top finance manager, previously spent more than a year in London working on a complex project. While on this assignment he formed tight bonds with many key managers and gained a comprehensive understanding of the business at the granular level. He assumed that he was next in line for the vice presidency. When William was selected, Leo either ignored him or communicated solely on a need-to-know basis.

The relationship never warmed, and unfortunately, the stakes kept getting higher. Starting with small differences on how to report data, the two men’s disagreements spread to issues about revamping the larger, complex financial system. Leo believed (as did his day-to-day boss, Jack, the head of Houston’s operation) that since Houston generated well over 50 percent of the profits for the division, any major, division-wide change should be approved by managers at that location. He directed his staff to continue to rely on the old system, did not devote adequate resources to test the new system, and communicated as little as possible with William. William found out indirectly that Leo was not supporting his efforts and set up a videoconference to discuss progress (or lack of) on testing the new system. Leo explained that he did not have sufficient staff to run parallel systems; the new system required more resources than were available. Then he exploded, letting loose these comments: “You picked this darn system because it’s based in Liverpool, not because it was robust enough to handle the business, especially over here. If you want it tested, send some of your people here on assignment. I don’t have the time, and neither do my people. If that’s not good enough, deal with Jack.” With that, Leo turned off the video and walked away.

Situations with similar issues and consequences to the one described occur far too frequently in business. What type of conflict is involved here? Standardizing financial reporting for the division across all locations was mandated, and parallel systems needed to be run. Performance conflict arose when William made testing the new system his priority, but Leo refused to commit the resources needed to run dual systems, to test the new one, and to meet the year-end deadline. More important, social conflict was involved as well. The root of this type of conflict is twofold: Leo resented William for getting a promotion he believed he deserved and did not cooperate with him from the beginning. William was not sensitive to Leo’s resentment and ignored the fact that this key player’s support was critical to his own success.

The situation could have been turned around with sensible, practical actions such as planning regular status meetings, during which the key players could have continually addressed deadline issues, and then putting in place relentless follow-up procedures. In addition, each team member should have had clear roles and responsibilities, with communication guidelines understood by all. Finally, accountability mechanisms needed to exist to build trust within the team. Both leaders made this situation worse by ignoring their differences, which were small at first, but grew to have larger implications for the entire division. Without communicating with each other their difficulties grew to the point that a key project was threatened. William should have understood earlier that Leo was not forthcoming or cooperative and tried to make him an ally through ongoing communications. Leo, as a key manager, should have seen the “larger picture” and put aside personal resentments to address business concerns. He could have asked William to work more closely with him to gain an understanding of what resources were available and how the finance area could best support the business, especially since Leo’s location was the most profitable in the division.

The social conflict elements are more difficult to defuse because they often simmer below the surface, and in business situations people prefer to avoid touchy-feely behavior. However, when one person is promoted over another, it makes sense for the new leader to recognize that it is in everyone’s best interests to reach out, build a bridge, and make the other party a partner. How to build that bridge depends on the flexibility of both individuals.

Resolution of the Conflict

What actually happened in this case? Text messages went flying across both sides of the Atlantic, and Jack quickly realized that this conflict would have a negative impact on the bottom line. At this point he called me in to help mediate the situation, which I diagnosed as involving both performance and social conflict.

To assess the situation I had individual videoconferences with Jack and Leo in Houston, and William in London. The facts I gleaned from these conversations were as follows: London HQ had committed to installing a new system; Leo was not committing the needed resources to test this system, with Jack’s tacit approval; William mandated an aggressive time line without securing necessary buy-in from key players at the location that drove the most revenue.

I then had several conversations with Jack (whose overriding concern was his location’s continued success) to teach him effective mediation techniques in the virtual world. I’ve learned that friction often occurs when people make their own assumptions that go unchallenged, especially when colleagues work virtually. When colleagues can walk into each other’s offices, issues often get resolved through face-to-face discussion—which is not an option in the virtual workplace.

In these circumstances, a structured approach is necessary. It was important for Jack to understand the big picture as well as Leo’s and William’s individual points of view. He spoke with each of them several times, making note when the two disagreed on specific situations. After Jack and I reviewed the overall situation, he was ready to hold the mediation call by videoconference. I sat in on this call as a consultant/partner, and my role was to watch the mediation process, monitor it, and keep things on track. First, Jack set the ground rules for the call. He explained that as the mediator, his responsibility was to make sure both Leo and William had the opportunity to present their perspectives. They were to keep emotion outside of the conversation and focus on what was in the division’s best interest. This is difficult to do, of course, when feelings are running high. This initial virtual meeting lasted over two hours. During this time both men stated their position, and when disagreements arose as to deadlines and available resources, Jack kept probing until they both agreed on what was possible. Finally, both Leo and William restated their positions, and Jack summarized the priorities. Another call was scheduled for the following week to resolve their differences, giving Leo and William time to align possible solutions with the goal of having the new financial system up and running by the new fiscal year.

During the next call, both men presented their plan for action. William agreed to assign several employees from headquarters to Houston for the next few months, and Leo agreed to devote more time to this key project. William also agreed to visit Houston to meet Leo and key managers within the next few weeks, providing an opportunity to establish a better working relationship with Leo. It was also agreed that a weekly videoconference would take place until the end of the fiscal year to monitor deadlines. The result was that the deadline was met and the new system was in place at all locations, simplifying global sales projections and analysis. Leo and William never became close friends, but they did overcome personal differences to meet organizational goals. And that, after all, is the aim of any successful mediation: to ensure that personal differences and underlying conflict do not derail organizational objectives.

Turning Lemons Into Lemonade—Productive Conflict Management

Lemons can taste sour, but added to water and sweetener, they are transformed into a wonderful beverage. Similarly, if you practice productive conflict management, you can turn potentially treacherous and risky situations into successful outcomes.

There are many ways for virtual managers to help mitigate conflict in their teams. The goal is to reduce conflict as soon as a problem is suspected, or before it begins to manifest itself. Anticipating conflict before it surfaces saves time later on, as well as potential expenses caused by work disruptions.

Tips for Handling Conflict Management in Virtual Teams

![]() Prepare employees for conflict; invest in training so that employees will be ready and willing to take ownership of their conflict situations.

Prepare employees for conflict; invest in training so that employees will be ready and willing to take ownership of their conflict situations.

![]() Make sure you schedule one-on-one time with each team member on a regular basis, and invite feedback.

Make sure you schedule one-on-one time with each team member on a regular basis, and invite feedback.

![]() Accept conflict as part of organizational life. Observe and acknowledge what has happened. Make it a point to notice what is going on.

Accept conflict as part of organizational life. Observe and acknowledge what has happened. Make it a point to notice what is going on.

![]() Make the first move toward resolving the conflict (i.e., take responsibility) because you do not want the situation to fester or become a stalemate.

Make the first move toward resolving the conflict (i.e., take responsibility) because you do not want the situation to fester or become a stalemate.

![]() Refer back to your Team Setup report (Chapter 2) and the Rules of the Road that you established earlier. You may want to revisit those rules from time to time and refresh the conflict behaviors for which you hold team members accountable.

Refer back to your Team Setup report (Chapter 2) and the Rules of the Road that you established earlier. You may want to revisit those rules from time to time and refresh the conflict behaviors for which you hold team members accountable.

![]() Communicate about the conflict. Don’t hold it in or be afraid to speak up. Express how the conflict makes you feel and how you see it. Reframe the conflict experience in terms of the bigger picture and not just the particular situation.

Communicate about the conflict. Don’t hold it in or be afraid to speak up. Express how the conflict makes you feel and how you see it. Reframe the conflict experience in terms of the bigger picture and not just the particular situation.

![]() Encourage employees to speak up and ask for help in resolving conflicts. Coach them to put themselves in the other person’s shoes to understand their coworker’s point of view.

Encourage employees to speak up and ask for help in resolving conflicts. Coach them to put themselves in the other person’s shoes to understand their coworker’s point of view.

![]() Use a structured approach and common language to address conflicts, and be flexible about possible resolutions.

Use a structured approach and common language to address conflicts, and be flexible about possible resolutions.

![]() Take care not to confront someone in public (during a conference call, for instance). Address conflicts in private with the appropriate individuals first.

Take care not to confront someone in public (during a conference call, for instance). Address conflicts in private with the appropriate individuals first.

![]() Learn from the conflict experience so that you can improve your skills in this area for the future.

Learn from the conflict experience so that you can improve your skills in this area for the future.

![]() Above all, choose your battles carefully. Don’t let the urgency of a request push you into giving an emotional response. Stay in control of yourself and calmly evaluate requests.

Above all, choose your battles carefully. Don’t let the urgency of a request push you into giving an emotional response. Stay in control of yourself and calmly evaluate requests.

Four Steps for Personally Handling Conflicts

1. Pause before responding.

2. Acknowledge the other person’s feelings/reactions.

3. Ask questions. Questioning gives you time to think and gain control. It also may provide you with new data and more clarity on what the other person is saying.

4. Suggest taking a break or continuing the conversation at a later point if you feel you need it.

Note: While your personal response is important, don’t take the situation personally. That is, acknowledge your emotions without acting on them, and focus instead on understanding and solving the problem.

Virtual Team Mediation Techniques

Virtual teams have a heightened awareness about the need to pay attention to their processes. In the traditional world, when conflict exists between two team members, you get them in the same room talking about an issue. In the virtual world, you are somewhat limited in your options. Most solutions rely on building virtual bridges to overcome physical distance. Your interactions are limited to phone or video communication, and the connection is surely not as immediate. As one virtual leader in a high-tech company said, “When you have a problem with someone who works in the same building or with a colleague in an intact team vs. a cross-functional team member, you handle it differently because the former is like a family. The solution might be the same [because you still have to bring the team together either face-to-face or virtually to work through the conflict issues], but your approach might change.”

One of the themes that I hear repeatedly, both through my consulting work and from the many interviews conducted for this book, is that virtual managers have to learn to become mediators. “I often act as a moderator when there is an argument between team members,” says a team leader at a global financial company. “One aspect of being virtual is that people use e-mail instead of the phone and create truth-avoiding conflict. If you were in an office, people would stop by your desk. In the virtual world, people can hide. So I solve problems over the telephone,” says a virtual manager at a consumer products company.

When conflict arises between virtual team members, it often has to be mediated over the telephone, a medium that offers advantages as well as disadvantages, as shown in Figure 5-5.

Although conducting a sensitive discussion by telephone is not the first choice, it is the best choice when it is not possible to meet in person. It still allows some level of sincerity and establishes real and direct (verbal) communication with those on the other end of the phone line.

Figure 5-5. Telephone conference call mediation.

Mediating Conflict Through a Conference Call

There are several effective virtual mediation tips that I recommend. Before the scheduled conference call, set ground rules for the conversation and be involved as the mediator in the discussion. Your role is to act as a moderator/facilitator/referee, helping people get to their own solutions. You can help prioritize and create alignment between their actions and goals. Many of the managers I interviewed have used the same technique. They hold one-on-one conversations with each team member before holding a joint conference call. These individual conversations are useful for clarifying issues, building trust, and minimizing politics.

Here are some further examples. You do not need to use all of them with your team. Choose the methods that can work for everyone.

Before the Conference Call (Setting Ground Rules)

![]() Recognize that everyone has an opinion about almost everything.

Recognize that everyone has an opinion about almost everything.

![]() Deal with realistic issues that are solvable.

Deal with realistic issues that are solvable.

![]() Acknowledge differences of opinion.

Acknowledge differences of opinion.

![]() Listen to other team members first; then decide how to respond.

Listen to other team members first; then decide how to respond.

![]() Express feelings and thoughts openly.

Express feelings and thoughts openly.

![]() Use I statements and specific examples.

Use I statements and specific examples.

![]() Be sure that labeling or insulting is off-limits.

Be sure that labeling or insulting is off-limits.

![]() Acknowledge that everyone takes responsibility for creating, promoting, or allowing the conflict.

Acknowledge that everyone takes responsibility for creating, promoting, or allowing the conflict.

![]() Work together on solutions.

Work together on solutions.

Establishing Your Role

![]() Clarify your role as referee/mediator/moderator.

Clarify your role as referee/mediator/moderator.

![]() Clarify your expectations.

Clarify your expectations.

![]() Encourage everyone to be honest.

Encourage everyone to be honest.

![]() Be fair and impartial—don’t take sides.

Be fair and impartial—don’t take sides.

Guiding the Process

Step 1. Open the discussion effectively without blaming anyone. The goal is to find commonalities and set the stage for open communication and motivated change. Acting as a referee, you are there to call things as you see them. You are not to take sides, but rather be the neutral party and clarify any misunderstandings.

Step 2. Get each person’s ideas and input first. Acknowledge all ideas without agreeing or disagreeing with them. Clarify the issues people have and help individuals share information.

Step 3. Present and compare ideas to foster discovery/dialogue and move toward action. Discuss the main virtual conflict issues (e.g., missing information, budget issues, communication style, work product). Clarify what is going on and have people take responsibility, even partial ownership of the issues.

Step 4. Specify actions and gain commitment to plans. Get greater involvement by building cohesiveness; focusing on the issues at hand (not on the people or personalities); and affirming direction, priorities, and plans. Remind teammates that they don’t have to be best friends, but they do need to work together. Confirm your support and promote learning from this experience.

Toward the end of the conference call, make sure that you reach some level of problem solving and that all conversations tie back to the goal of the team/project/result. Although their approaches or styles might differ, people actually want similar things. They may argue on the call because they are ambitious or competitive. They may even raise their tone a bit or ignore (back away from) the conflict, but most of the time people want to be part of something, they want to solve the problem, and they want to be successful. As a manager, you are there to facilitate: Engage the conversation; ask the parties to respond; and then, together, find a solution. Here are a few additional tips for handling the call itself:

![]() Pay extra attention to your tone of voice, to be sure you are conveying the right message.

Pay extra attention to your tone of voice, to be sure you are conveying the right message.

![]() Confirm with the other people on the call that your intention is being heard, and do so frequently during the call.

Confirm with the other people on the call that your intention is being heard, and do so frequently during the call.

![]() Eliminate distractions that can take your focus away from the conversation.

Eliminate distractions that can take your focus away from the conversation.

![]() Do not multitask while on the call.

Do not multitask while on the call.

![]() Listen for cues that may be inconsistent with the words the other person is saying (e.g., Do people hesitate or lower their tone of voice? Do you detect uncertainty in someone’s voice? Is anyone saying yes too quickly?).

Listen for cues that may be inconsistent with the words the other person is saying (e.g., Do people hesitate or lower their tone of voice? Do you detect uncertainty in someone’s voice? Is anyone saying yes too quickly?).

CASE STUDY

Can Oil and Water Ever Mix?

One client, a virtual manager at a software company, shared this story of virtual mediation:

“Two of my employees had different approaches to getting the work done and a strong lack of tolerance for each other. Mark was a task-oriented project manager: Type A personality, a go-getter, a ‘just do it and get it done’ guy. Gary was a software developer, a ‘wait a minute’ personality who was very careful and methodical in his work. They clashed and the relationship deteriorated. Mark kept saying that Gary was not performing, and Gary complained that due diligence was not getting done and mistakes were bound to happen. At first I thought that work was not getting done. I called both of them to find out what each thought the problem was. It turned out that the work was getting done, but there was unnecessary friction along the way. Both individuals stressed that they had trouble getting their message across to the other. Gary, the software developer, didn’t express himself in the [way] that Mark, the project manager, wanted him to. I realized that their different communication styles led to this rift. These two people were flamed up with each other.

“Here’s the process I took to resolve this situation. First, I conducted several one-on-one sessions with each employee. Second, I then mediated a conference call with both [of them], which began with both employees stating what they wanted to accomplish. Fortunately, they agreed on the end result—a successful project. Third, they discussed the work and agreed that wasn’t the issue: The disagreement was about the means to achieving this end; that is, the approach. Fourth, we talked about communicating in ways that [would allow them to] help each other. I said to Mark, ‘Okay, when you ask Gary about [a specific issue], it affects him in such and such a way.’ Mark then said, ‘When Gary says [a specific thing], I think he is not doing the work.’ So we had to get beyond the styles and understand how to communicate intentions so that the conversation could improve.”

What was the outcome? According to the manager, “They worked on this project until it was completed, and the work continued to get done. They knew they disagreed about style, and it took a continuous effort to keep the communication going. We did that through multiple calls. Once the project ended successfully, Gary and Mark moved on to another virtual project.”

What If Your Best Efforts at Mediating Conflict Fail?

If you try to mediate a conflict but cannot resolve it, you may have to separate the parties. Blaming yourself or others wastes energy; sometimes resolution is not possible. If the virtual conflict has festered too long, the parties may not be willing to put the effort into working out the issue, or the project starts moving in a different direction. You may need to find another role for a team member, or even transition an individual out of the team. As one virtual leader at a global consumer products company commented, “If the problem person keeps doing things in the same way after the mediated calls, I separate [the individual] or even manage the person out of the group.”

If a toxic conflict still exists, estimate its true cost, including the cost of not meeting deadlines or missing a target date to launch a new product. Compare this cost with the expense of bringing everyone together for an in-person meeting. After you complete the evaluation, if it is appropriate, schedule your meeting.

In a Nutshell—Reducing Virtual Team Conflict

The most productive approach to dealing with conflict in virtual teams is to take steps that actually reduce the potential for conflict before it occurs. Teams do this in a number of ways: Team members sensitize each other to their individual preferences; they cross-train to learn and appreciate each other’s perspective on tasks; they produce and follow guidelines (Rules of the Road and a Team Code) on how to operate. This last method is simple yet very successful. If team members know, understand, and agree on a set of rules for diffusing conflict, then they will be more effective as a team.

Along with the many other lessons offered throughout the chapter, here are some final tips for reducing virtual team conflict:

![]() Continually monitor, manage, and diffuse potential conflict situations.

Continually monitor, manage, and diffuse potential conflict situations.

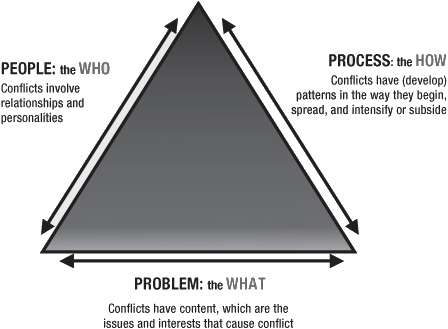

![]() Use the three Ps of conflict resolution to understand the People and the Process involved and the Problem to be solved.

Use the three Ps of conflict resolution to understand the People and the Process involved and the Problem to be solved.

![]() Don’t pass work on to another team member in a form you wouldn’t want to receive it.

Don’t pass work on to another team member in a form you wouldn’t want to receive it.

![]() Don’t accept such work from someone else.

Don’t accept such work from someone else.

![]() Assumptions are risky; make them only when you have to.

Assumptions are risky; make them only when you have to.

![]() Clarify where your responsibility starts and stops, and how it fits with that of other team members.

Clarify where your responsibility starts and stops, and how it fits with that of other team members.

![]() Update people who need to know what you know.

Update people who need to know what you know.

![]() If you have an issue or a point of disagreement with a team member, tell that person, not others.

If you have an issue or a point of disagreement with a team member, tell that person, not others.

![]() Try to resolve conflicts early (as soon as you sense some tension or misunderstanding).

Try to resolve conflicts early (as soon as you sense some tension or misunderstanding).

![]() Take time to explain and talk with others about the issues.

Take time to explain and talk with others about the issues.

![]() Seek to understand first before being understood.

Seek to understand first before being understood.

![]() Strive for open and honest team relations.

Strive for open and honest team relations.

![]() Turn conflicts into problem-solving opportunities.

Turn conflicts into problem-solving opportunities.

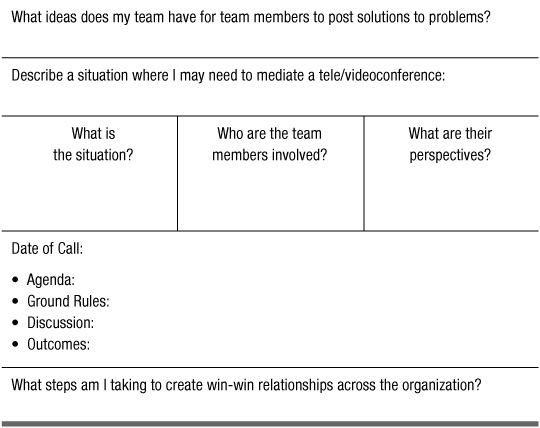

Use the following Virtual Roadmap exercise, written as a series of questions, to review the lessons in proactive conflict management offered in this chapter. These questions will help you plan ways to solve problems in the virtual world.

YOUR VIRTUAL ROADMAP TO PRODUCTIVE CONFLICT MANAGEMENT