Bill Gates was standing in the right place in the early 1980s when IBM's fledgling personal computer business came looking for an operating system. Gates didn't have one, but his partner, Paul Allen, knew someone who did. Gates paid $75,000 for QDOS (Quick and Dirty Operating System) in the deal—or steal—of the twentieth century. Gates changed the name to DOS and resold it to IBM, but shrewdly retained the right to license it to anyone else. DOS quickly became the primary operating system for most of the world's personal computers. Gates himself was on the road to becoming one of the world's richest men (Manes and Andrews, 1994; Zachary, 1994).

Windows, a graphic interface riding atop DOS, fueled another great leap forward for the Microsoft empire. But by the late 1980s, Gates had a problem. He and everyone else knew that DOS was obsolete and woefully deficient. The solution was supposed to be OS/2, a new operating system developed jointly by Microsoft and IBM, but it was a tense partnership. IBMers saw "Microsofties" as undisciplined adolescents. Microsoft folks moaned that "Big Blue" was a hopelessly bureaucratic producer of "poor code, poor design, and poor process" (Manes and Andrews, 1994, p. 425). Increasingly pessimistic about the viability of OS/2, Gates decided to hedge his bets by developing a new operating system to be called Windows NT. Gates recruited the brilliant but crotchety Dave Cutler from Digital Equipment to head the effort. Cutler had led the development of the operating system that helped DEC dominate the minicomputer industry.

Gates recognized that Cutler was known "more for his code than his charm" (Zachary, 1993, p. A1). Things started well, but Cutler insisted on keeping his team small and wanted no responsibility beyond the "kernel" of the operating system. He figured someone else could worry about details like the user interface. Gates began to see a potential disaster looming, but issuing orders to the temperamental Cutler was as promising as telling Picasso how to paint. So Gates put the calm, understated Paul Maritz on the case. Born in South Africa, Maritz had studied mathematics and economics in Cape Town before deciding that software was his destiny. He joined Microsoft in 1986 and became the leader of its OS/2 effort. When he was assigned informal oversight of Windows NT, he got a frosty welcome:

As he began meeting regularly with Cutler on NT matters, Maritz often found himself the victim of slights. Once Maritz innocently suggested to Cutler that "We should—" Cutler interrupted, "We! Who's we? You mean you and the mouse in your pocket?" Maritz brushed off such retorts, even finding humor in Cutler's apparently inexhaustible supply of epithets. He refused to allow Cutler to draw him into a brawl. Instead, he hoped Cutler would "volunteer" for greater responsibility as the shortcomings of the status quo became more apparent [Zachary, 1994, p. 76].

Maritz enticed Cutler with tempting challenges. In early 1990, he asked Cutler if he could put together a demonstration of NT for COMDEX, the industry's biggest trade show. Cutler took the bait. Maritz knew that the effort would expose NT's weaknesses (Zachary, 1994). When Gates subsequently seethed that NT was too late, too big, and too slow, Maritz scrambled to "filter that stuff from Dave" (p. 208). Maritz's patience eventually paid off when he was promoted to head all operating systems development:

The promotion gave Maritz formal and actual authority over Cutler and the entire NT project. Still, he avoided confrontations, preferring to wait until Cutler came to see the benefits of Maritz's views. Increasingly Cutler and his inner circle viewed Maritz as a powerhouse, not an empty suit. "He's critical to the project," said [one of Cutler's most loyal lieutenants]. "He got into it a little bit at a time. Slowly he blended his way in until it was obvious who was running the show. Him" [p. 204].

Chapter Nine's account of the Columbia and Challenger cases drives home a chilling lesson about political pressures sidetracking momentous decisions. The implosion of firms such as Enron and WorldCom shows how the unfettered pursuit of self-interest by powerful executives can bring even a huge corporation to its knees. Many believe that the antidote is to get politics out of management. But this is unrealistic so long as politics is inseparable from social life. Enduring differences lead to multiple interpretations of what's true and what's important. Scarce resources trigger contests about who gets what. Interdependence means that people cannot ignore one another; they need each other's assistance, support, and resources. Under such conditions, efforts to eliminate politics are futile and counterproductive. In our search for more positive images of the manager as constructive politician, Paul Maritz's deft combination of patience, persistence, and diplomacy offers an instructive example.

Kotter (1985) contends that too many managers are either naive or cynical about organizational politics. Pollyannas view the world through rose-colored glasses, insisting that most people are good, kind, and trustworthy. Cynics believe the opposite: everyone is selfish, things are always cutthroat, and "get them before they get you" is the best survival tactic. Brown and Hesketh (2004) documented similar contrasting stances among college job seekers. The naive "purists" believe that hiring is fair and that, if they present themselves honestly, they'll be rewarded on their merits. The more cynical "players" game the system and try to present the self they think employers want. In Kotter's view, neither extreme is realistic or effective: "Organizational excellence ... demands a sophisticated type of social skill: a leadership skill that can mobilize people and accomplish important objectives despite dozens of obstacles; a skill that can pull people together for meaningful purposes despite the thousands of forces that push us apart; a skill that can keep our corporations and public institutions from descending into a mediocrity characterized by bureaucratic infighting, parochial politics, and vicious power struggles" (p. 11).

Organizations now more than ever need "benevolent politicians" who can find a middle course: "Beyond the yellow brick road of naïveté and the mugger's lane of cynicism, there is a narrow path, poorly lighted, hard to find, and even harder to stay on once found. People who have the skill and the perseverance to take that path serve us in countless ways. We need more of these people. Many more" (Kotter, 1985, p. xi).

In a world of chronic scarcity, diversity, and conflict, the nimble manager has to walk a tightrope: developing a direction, building a base of support, and cobbling together working relations with both allies and opponents. In this chapter, we discuss why this is vital and then lay out the basic skills of the manager as politician. Finally, we tackle ethical issues, the soft underbelly of organizational politics. Is it possible to be political and still do the right thing? We discuss four instrumental values to guide ethical choice.

The manager as politician exercises four key skills: agenda-setting (Kanter, 1983; Kotter, 1988; Pfeffer, 1992; Smith, 1988), mapping the political terrain (Pfeffer, 1992; Pichault, 1993), networking and forming coalitions (Kanter, 1983; Kotter, 1982, 1985, 1988; Pfeffer, 1992; Smith, 1988), and bargaining and negotiating (Bellow and Moulton, 1978; Fisher and Ury, 1981; Lax and Sebenius, 1986).

Agenda Setting

Structurally, an agenda outlines a goal and a schedule of activities. Politically, an agenda is a statement of interests and a scenario for getting the goods. In reflecting on his experience as a university president, Warren Bennis arrived at a deceptively simple observation: "It struck me that I was most effective when I knew what I wanted" (1989, p. 20). Kanter's study of internal entrepreneurs in American corporations (1983), Kotter's analysis of effective corporate leaders (1988), and Smith's examination of effective U.S. presidents (1988) all reached a similar conclusion: whether you're a middle manager or the CEO, the first step in effective political leadership is setting an agenda.

The effective leader creates an "agenda for change" with two major elements: a vision balancing the long-term interests of key parties, and a strategy for achieving the vision while recognizing competing internal and external forces (Kotter, 1988). The agenda must convey direction while addressing concerns of major stakeholders. Kanter (1983) and Pfeffer (1992) underscore the intimate tie between gathering information and developing a vision. Pfeffer's list of key political attributes includes "sensitivity"—knowing how others think and what they care about so that your agenda responds to their concerns: "Many people think of politicians as arm-twisters, and that is, in part, true. But in order to be a successful arm-twister, one needs to know which arm to twist, and how" (p. 172).

Kanter adds: "While gathering information, entrepreneurs can also be 'planting seeds' —leaving the kernel of an idea behind and letting it germinate and blossom so that it begins to float around the system from many sources other than the innovator" (1983, p. 218). Paul Maritz did just that. Ignoring Dave Cutler's barbs and insults, he focused on getting information, building relationships, and formulating an agenda. He quickly concluded that the NT project was in disarray and that Cutler had to take on more responsibility. Maritz's strategy was attuned to his quarry: "He protected Cutler from undue criticism and resisted the urge to reform him. [He] kept the peace by exacting from Cutler no ritual expressions of obedience" (Zachary, 1994, pp. 281–282).

A vision without a strategy remains an illusion. A strategy has to recognize major forces working for and against the agenda. Smith's point about U.S. presidents is relevant to managers at every level:

The paramount task and power of the president is to articulate the national purpose: to fix the nation's agenda. Of all the big games at the summit of American politics, the agenda game must be won first. The effectiveness of the presidency and the capacity of any president to lead depend on focusing the nation's political attention and its energies on two or three top priorities. From the standpoint of history, the flow of events seems to have immutable logic, but political reality is inherently chaotic: it contains no automatic agenda. Order must be imposed [1988, p. 333].

Agendas never come neatly packaged. The bigger the job, the harder it is to wade through the clutter and find order amid chaos. Contrary to Woody Allen's dictum, success requires more than just showing up. High office, even if the incumbent enjoys great personal popularity, is no guarantee. In his first year as president, Ronald Reagan was remarkably successful following a classic strategy for winning the agenda game: "First impressions are critical. In the agenda game, a swift beginning is crucial for a new president to establish himself as leader—to show the nation that he will make a difference in people's lives. The first one hundred days are the vital test; in those weeks, the political community and the public measure a new president—to see whether he is active, dominant, sure, purposeful" (Smith, 1988, p. 334).

Reagan began with a vision but without a strategy. He was not gifted as a manager or a strategist, despite extraordinary ability to portray complex issues in broad, symbolic brushstrokes. Reagan's staff painstakingly studied the first hundred days of four predecessors. They concluded that it was essential to move with speed and focus. Pushing competing issues aside, they focused on two: cutting taxes and reducing the federal budget. They also discovered a secret weapon in David Stockman, the only person in the Reagan White House who understood the federal budget process. "Stockman got a jump on everyone else for two reasons: he had an agenda and a legislative blueprint already prepared, and he understood the real levers of power. Two terms as a Michigan congressman plus a network of key Republican and Democratic connections had taught Stockman how to play the power game" (Smith, 1988, p. 351). Reagan and his advisers had the vision; Stockman provided strategic direction.

Mapping the Political Terrain

It is foolhardy to plunge into a minefield without knowing where explosives are buried, yet managers unwittingly do it all the time. They launch a new initiative with little or no effort to scout and master the political turf. Pichault (1993) suggests four steps for developing a political map:

Determine channels of informal communication.

Identify principal agents of political influence.

Analyze possibilities for mobilizing internal and external players.

Anticipate counterstrategies that others are likely to employ.

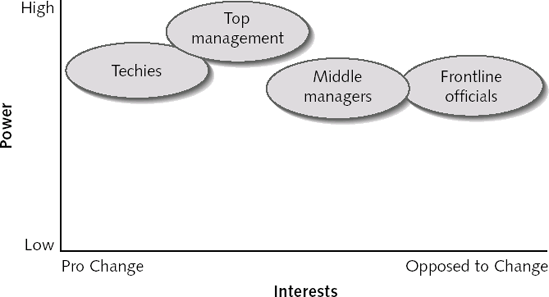

Pichault offers an example of planned change in a large government agency in Belgium. The agency wanted to replace antiquated manual records with a fully automated paperless computer network. But proponents of the new system had virtually no understanding of how work got done. Nor did they anticipate the interests and power of key middle managers and frontline bureaucrats. It seemed obvious to the techies that better data meant higher efficiency. In reality, frontline bureaucrats made little use of the data. They applied standard procedures in 90 percent of cases and asked their bosses what to do about the rest. Their queries were partly to get the "right" answer, but even more to get political cover. Since they saw no need for the new technology, frontline bureaucrats were likely to ignore or work around it. After a consultant clarified the political map, a new battle erupted between unrepentant techies, who insisted their solution was correct, and senior managers who argued for a less ambitious approach. The two sides ultimately compromised.

A simple way to develop a political map for any situation is to create a two-dimensional diagram mapping players (who is in the game), power (how much clout each player is likely to exercise), and interests (what each player wants). Exhibits 10.1 and 10.2 present two hypothetical versions of the Belgian bureaucracy's political map. Exhibit 10.1 shows the map as the techies saw it. They expected little opposition and assumed they held all the high cards; that implied a quick and easy win. Exhibit 10.2, a more objective map, paints a very different picture. Resistance is more intense and opponents more powerful. This view forecasts a stormy process with protracted conflict. Though less comforting, the second map has an important message: success requires substantial effort to realign the political force field. The third and fourth key skills of the manager as politician, discussed in the next two sections, include strategies for doing that.

Networking and Building Coalitions

Managers often fail to get things done because they rely too much on reason and too little on relationships. In both the Challenger and Columbia space shuttle catastrophes (discussed in Chapter Nine), engineers pitched careful, data-based arguments to their superiors about potentially lethal safety risks—and failed to dent their bosses' resistance (Glanz and Schwartz, 2003; Vaughn, 1995). Six months before the Challenger accident, for example, an engineer at Morton Thiokol wrote to management: "The result [of an O-ring failure] would be a catastrophe of the highest order—loss of human life" (Bell and Esch, 1987, p. 45). A memo, if it is clear and powerful, may work, but is often a sign of political innocence. Kotter (1985) suggests four basic steps for exercising political influence:

Identify relevant relationships. (Figure out which players you need to influence.)

Assess who might resist, why, and how strongly. (Determine where the leadership challenges will be.)

Develop, wherever possible, links with potential opponents to facilitate communication, education, or negotiation. (Hold your enemies close.)

If step three fails, carefully select and implement either more subtle or more forceful methods. (Save your big guns until you really need them, but have a Plan B in case Plan A falls short.)

These steps underscore the importance of developing a power base. Moving up the managerial ladder confers authority but also creates more dependence, because success requires the cooperation of many others (Kotter, 1985, 1988; Butcher and Clarke, 2001). People rarely give their best efforts and fullest cooperation simply because they have been ordered to do so. They accept direction better when they perceive the people in authority as credible, competent, and sensible.

The first task in building networks and coalitions is to figure out whose help you need. The second is to develop relationships so people will be there when you need them. Successful middle-management change agents typically begin by getting their boss on board (Kanter, 1983). They then move to "preselling," or "making cheerleaders": "Peers, managers of related functions, stakeholders in the issue, potential collaborators, and sometimes even customers would be approached individually, in one-on-one meetings that gave people a chance to influence the project and [gave] the innovator the maximum opportunity to sell it. Seeing them alone and on their territory was important: the rule was to act as if each person were the most important one for the project's success" (p. 223).

Once you cultivate cheerleaders, you can move to "horse trading": promising rewards in exchange for resources and support. This builds a resource base that helps in "securing blessings," or getting the necessary approvals and mandates from higher management (Kanter, 1983). Kanter found that the usual route to success in securing blessings is to identify critical senior managers and to develop a polished, formal presentation to nail down their support. The best presentations respond to both substantive and political concerns. Senior managers typically care about two questions: Is it a good idea? How will my constituents react? Once innovators get a nod from higher management, they can formalize the coalition with their boss and make specific plans for pursuing the project.

The basic point is simple: as a manager, you need friends and allies to get things done. To sew up their support, you need to build coalitions. Rationalists and romantics sometimes react with horror to this scenario. Why should you have to play political games to get something accepted if it's the right thing to do? One of the great works in French drama, Molière's The Misanthrope, tells the story of a protagonist whose rigid rejection of all things political is destructive for him and everyone close by. The point that Molière made four centuries ago still holds: it is hard to dislike politics without also disliking people. Like it or not, political dynamics are inevitable under three conditions most managers face every day: ambiguity, diversity, and scarcity.

Informal networks perform a number of functions that formal structure may do poorly or not at all—moving projects forward, imparting culture, mentoring, and creating "communities of practice." Some organizations use measures of social networking to identify and manage who's connected to whom. When Procter & Gamble studied linkages among its twenty-five research and development units around the world, it discovered its unit in China was relatively isolated from all the rest—a clear signal that linkages needed to be improved to corner a big and growing market (Reingold and Yang, 2007).

Ignoring or misreading people's roles in networks is costly. Consider the mistake that undermined John LeBoutillier's political career. Shortly after he was elected to Congress from a wealthy district in Long Island, LeBoutillier fired up his audience at the New York Republican convention with the colorful quip that Speaker of the House Thomas P. O'Neill, was "fat, bloated and out of control, just like the Federal budget." Asked to comment, Tip O'Neill was atypically terse: "I wouldn't know the man from a cord of wood" (Matthews, 1999, p. 113). Two years later, LeBoutillier unexpectedly lost his bid for reelection to an unknown opponent who didn't have the money to mount a real campaign—until a mysterious flood of contributions poured in from all over America. When LeBoutillier later ran into O'Neill, he admitted sheepishly, "I guess you were more popular than I thought you were" (Matthews, 1999, p. 114). LeBoutillier learned the hard way that it is dangerous to underestimate or provoke people when you don't know how much power they have or who their friends are.

Bargaining and Negotiation

We often associate bargaining with commercial, legal, and labor relations transactions. From a political perspective, though, bargaining is central to decision making. The horse trading Kanter describes as part of coalition building is just one of many examples. Negotiation is needed whenever two or more parties with some interests in common and others in conflict need to reach agreement. Labor and management may agree that a firm should make money and offer good jobs to employees but part ways on how to balance pay and profitability. Engineers and managers in the NASA space program had a common interest in the success of the shuttle flights, but at key moments differed sharply on how to balance technical and political trade-offs.

A fundamental dilemma in negotiations is choosing between "creating value" and "claiming value" (Lax and Sebenius, 1986). Value creators believe that successful negotiators must be inventive and cooperative in searching for a win-win solution. Value claimers see "win-win" as naively optimistic. For them, bargaining is a hard, tough process in which you have to do what it takes to win as much as you can.

One of the best-known win-win approaches to negotiation was developed by Fisher and Ury (1981) in their classic Getting to Yes. They argue that people too often engage in "positional bargaining": they stake out positions and then reluctantly make concessions to reach agreement. Fisher and Ury contend that positional bargaining is inefficient and misses opportunities to create something that's better for everyone. They propose an alternative: "principled bargaining," built around four strategies.

The first strategy is to separate people from the problem. The stress and tension of negotiations can easily escalate into anger and personal attack. The result is that a negotiator sometimes wants to defeat or hurt the other party at almost any cost. Because every negotiation involves both substance and relationship, the wise negotiator will "deal with the people as human beings and with the problem on its merits." Paul Maritz demonstrated this principle in dealing with the prickly Dave Cutler. Even though Cutler continually baited and insulted him, Maritz refused to be distracted and persistently focused on getting the job done.

The second strategy is to focus on interests, not positions. If you get locked into a particular position, you might overlook better ways to achieve your goal. An example is the 1978 Camp David treaty between Israel and Egypt. The sides were at an impasse over where to draw the boundary between the two countries. Israel wanted to keep part of the Sinai, while Egypt wanted all of it back. Resolution became possible only when they looked at underlying interests. Israel was concerned about security: no Egyptian tanks on the border. Egypt was concerned about sovereignty: the Sinai had been part of Egypt from the time of the Pharaohs. The parties agreed on a plan that gave all of the Sinai back to Egypt while demilitarizing large parts of it (Fisher and Ury, 1981). That solution led to a durable peace agreement.

Fisher and Ury's third strategy is to invent options for mutual gain instead of locking on to the first alternative that comes to mind. More options increase the chance of a better outcome. Maritz recognized this in his dealings with Cutler. Instead of bullying, he asked innocently, "Could you do a demo at COMDEX?" It was a new option that created gains for both parties.

Fisher and Ury's fourth strategy is to insist on objective criteria—standards of fairness for both substance and procedure. Agreeing on criteria at the beginning of negotiations can produce optimism and momentum, while reducing the use of devious or provocative tactics that get in the way of a mutually beneficial solution. When a school board and a teachers' union are at loggerheads over the size of a pay increase, they can look for independent standards, such as the rate of inflation or the terms of settlement in other districts. A classic example of fair procedure finds two sisters deadlocked over how to divide the last wedge of pie between them. They agree that one will cut the pie into two pieces and the other will choose the piece that she wants.

Fisher and Ury devote most of their attention to creating value—finding better solutions for both parties. They downplay the question of claiming value. Yet there are many examples in which shrewd value claimers have come out ahead. In 1980, Bill Gates offered to license an operating system to IBM about forty-eight hours before he had one to sell. Then he neglected to mention to QDOS's owner, Tim Paterson of Seattle Computer, that Microsoft was buying his operating system to resell it to IBM. Gates gave IBM a great price: only $30,000 more than the $50,000 he'd paid for it. But he retained the rights to license it to anyone else. At the time, Microsoft was a flea atop IBM's elephant. Almost no one except Gates saw the possibility that consumers would want an IBM computer made by anyone but IBM. IBM negotiators might well have thought they were stealing candy from babies in buying DOS royalty-free for a measly $80,000. Meanwhile, Gates was already dreaming about millions of computers running his code. As it turned out, the new PC was an instant hit, and IBM couldn't make enough of them. Within a year, Microsoft had licensed MS-DOS to fifty companies, and the number kept growing (Mendelson and Korin, n.d.). Twenty years later, onlookers who wondered why Microsoft was so aggressive and unyielding in battling government antitrust suits might not have known that Gates had always been a dogged value claimer.

A classic treatment of value claiming is Schelling's 1960 essay The Strategy of Conflict, which focuses on how to make a credible threat. Suppose, for example, that I want to buy your house and am willing to pay $250,000. How can I convince you that I'm willing to pay only $200,000? Contrary to a common assumption, I'm not always better off if I'm stronger and have more resources. If you believe that I'm very wealthy, you might take my threat less seriously than if I can get you to believe that $200,000 is the furthest I can go. Common sense also suggests that I should be better off if I have considerable freedom of action. Yet I may get a better price if I can convince you my hands are tied—for example, I'm negotiating for a very stubborn buyer who won't go above $200,000, even if the house is worth more. Such examples suggest that the ideal situation for a bargainer is to have substantial resources and freedom while convincing the other side of the opposite. Value claiming provides its own slant on the bargaining process:

Bargaining is a mixed-motive game. Both parties want an agreement but have differing interests and preferences, so that what seems valuable to one is insignificant to the other.

Bargaining is a process of interdependent decisions. What each party does affects the other. Each player wants to be able to predict what the other will do while limiting the other's ability to reciprocate.

The more player A can control player B's level of uncertainty, the more powerful A is. The more A can keep private—as Bill Gates did with Seattle Computer and IBM—the better.

Bargaining involves judicious use of threats rather than sanctions. Players may threaten to use force, go on strike, or break off negotiations. In most cases, they prefer not to bear the costs of carrying out the threat.

Making a threat credible is crucial. A threat works only if your opponent believes it. Noncredible threats weaken your bargaining position and confuse the process.

Calculation of the appropriate level of threat is also critical. If I underthreaten, you may think I'm weak. If I overthreaten, you may not believe me, may break off the negotiations, or may escalate your own threats.

Creating value and claiming value are both intrinsic to the bargaining process. How does a manager decide how to balance the two? At least two questions are important: How much opportunity is there for a win-win solution? And will I have to work with these people again? If an agreement can make everyone better off, it makes sense to emphasize creating value. If you expect to work with the same people in the future, it is risky to use scorched-earth tactics that leave anger and mistrust in their wake. Managers who get a reputation for being manipulative, self-interested, or untrustworthy have a hard time building the networks and coalitions they need for future success.

Axelrod (1980) found that a strategy of conditional openness works best when negotiators need to work together over time. This strategy starts with open and collaborative behavior and maintains the approach if the other responds in kind. If the other party becomes adversarial, however, the negotiator responds accordingly and remains adversarial until the opponent makes a collaborative move. It is, in effect, a friendly and forgiving version of tit for tat—do unto others as they do unto you. Axelrod's research discovered that this conditional openness approach worked better than even the most fiendishly diabolical adversarial strategy.

A final consideration in balancing collaborative and adversarial tactics is ethics. Bargainers often deliberately misrepresent their positions—even though lying is almost universally condemned as unethical (Bok, 1978). This leads to a tricky question for the manager as politician: What actions are ethical and just?

Block (1987), Burns (1978), Lax and Sebenius (1986), and Messick and Ohme (1998) explore ethical issues in bargaining and organizational politics. Block's view asserts that individuals empower themselves through understanding: "The process of organizational politics as we know it works against people taking responsibility. We empower ourselves by discovering a positive way of being political. The line between positive and negative politics is a tightrope we have to walk" (1987, p. xiii).

Block argues that bureaucratic cycles often leave individuals feeling vulnerable, powerless, and helpless. If we confer too much power on the organization or others, we fear that the power will be used against us. Consequently, we develop manipulative strategies to protect ourselves. To escape the dilemma, managers need to support organizational structures, policies, and procedures that promote empowerment. They must also empower themselves.

Block urges managers to begin by building an "image of greatness" —a vision of what their department can contribute that is meaningful and worthwhile. Then they need to build support for their vision by negotiating a binding pact of agreement and trust. Block suggests treating friends and opponents differently. Adversaries, he says, are simultaneously the most difficult and most interesting people to deal with. It is usually ineffective to pressure them; a better strategy is to "let go of them." He offers four steps for letting go: (1) tell them your vision, (2) state your best understanding of their position, (3) identify your contribution to the problem, and (4) tell them what you plan to do without making demands. It's a variation on Axelrod's strategy of conditional openness.

Although this strategy may work in favorable conditions, it can backfire with a formidable, hard-headed opponent in a situation of scarce resources and durable differences. Bringing politics into the open may make conflict more obvious and overt but offer little hope of resolution. Block argues that "war games in organizations lose their power when brought into the light of day" (1987, p. 148), but wise managers will test that assumption against their circumstances.

Burns's conception of positive politics (1978) draws on examples as diverse and complex as Franklin Roosevelt and Adolph Hitler, Gandhi and Mao, Woodrow Wilson and Joan of Arc. He sees conflict and power as central to leadership. Searching for firm moral footing in a world of cultural and ethical diversity, Burns turned to Maslow's (1954) theory of motivation and Kohlberg's (1973) treatment of ethics.

From Maslow, he borrowed the hierarchy of motives (see Chapter Six). Moral leaders, he argued, appeal to higher-order human needs. Kohlberg supplied the idea of stages of moral reasoning. At the lowest, "preconventional" level, moral judgment is based primarily on perceived consequences: an action is right if you are rewarded and wrong if you are punished. In the intermediate or "conventional" level, the emphasis is on conforming to authority and established rules. At the highest, "postconventional" level, ethical judgment rests on general principles: the greatest good for the greatest number, or universal moral principles.

Maslow and Kohlberg intertwined gave Burns a foundation for constructing a positive view of politics: "If leaders are to be effective in helping to mobilize and elevate their constituencies, leaders must be whole persons, persons with full functioning capacities for thinking and feeling. The problem for them as educators, as leaders, is not to promote narrow, egocentric self-actualization, but to extend awareness of human needs and the means of gratifying them, to improve the larger social situation for which educators or leaders have responsibility and over which they have power" (1978, pp. 448–449).

Burns's view provides two expansive criteria: Does your leadership rest on general moral principles? And does it appeal to the "better angels" in your constituents' psyches? Lax and Sebenius (1986) see ethical issues as inescapable quandaries but provide a concrete set of questions for assessing leaders' actions:

Are you following rules that are mutually understood and accepted? In poker, for example, everyone understands that bluffing is part of the game but pulling cards from your sleeve is not.

Are you comfortable discussing and defending your choices? Would you want your colleagues and friends to know what you're doing? Your spouse, children, or parents? Would you be comfortable if your deeds appeared in your local newspaper?

Would you want to be on the receiving end of your own actions? Would you want this done to a member of your family?

What if everyone acted as you did? Would the impact on society be desirable? If you were designing an organization, would you want people to follow your example? Would you teach your children the ethics you have embraced?

Are there alternatives you could consider that rest on firmer ethical ground? Could you test your strategy with a trusted adviser and explore other options?

Although these questions may not tally up to a comprehensive ethical framework, they embody four important principles of moral judgment. They are instrumental values—guidelines about right actions rather than right outcomes. Four solidly anchored principles do not guarantee success, but they reduce ethical risks of taking a particular course of action.

Mutuality. Are all parties to a relationship operating under the same understanding about the rules of the game? Enron's Ken Lay was talking up the company's stock to analysts and employees even as he and others were selling their shares. In the period when WorldCom improved its profits by cooking the books, it made its competitors look bad. Top executives at competing firms such as AT&T and Sprint felt the heat from analysts and shareholders and wondered, "Why can't we get the results they're getting?" Only later did they learn the answer: "They're cheating, and we're not."

Generality. Does a specific action follow a principle of moral conduct applicable to comparable situations? When Enron and WorldCom violated accounting principles to inflate their results, they were secretly breaking the rules, not adhering to a broadly applicable rule of conduct.

Openness. Are we willing to make our thinking and decisions public and confrontable? As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes observed many years ago, "Sunlight is the best disinfectant." Keeping others in the dark was a consistent theme in the corporate ethics scandals of 2001–2002. Enron's books were almost impenetrable, and the company attacked analysts who questioned the numbers. Enron's techniques for manipulating the California energy crisis had to be clandestine to work. One device involved creating the appearance of congestion in the California power grid and subsequently getting paid for "moving energy to relieve congestion without actually moving any energy or relieving any congestion" (Oppel, 2002, p. A1).

Caring. Does this action show concern for the legitimate interests and feelings of others? Enron's effort to protect its share price by locking in employees so they couldn't sell the Enron shares in their retirement accounts, even as the value of the shares plunged, put the interests of senior executives ahead of everyone else's.

The scandals of the early 2000s were not unprecedented; such a wave is a predictable feature of the trough following every business boom. The 1980s, for example, gave us Ivan Boesky and the savings and loan crisis. There was another wave of corporate scandals in the 1970s. In the 1930s, the president of the New York Stock Exchange went to jail in his three-piece suit (Labaton, 2002). There will always be temptation whenever gargantuan egos and large sums of money are at stake. Top managers too rarely think or talk about the moral dimension of management and leadership. Porter notes the dearth of such conversation:

In a seminar with seventeen executives from nine corporations, we learned how the privatization of moral discourse in our society has created a deep sense of moral loneliness and moral illiteracy; how the absence of a common language prevents people from talking about and reading the moral issues they face. We learned how the isolation of individuals—the taboo against talking about spiritual matters in the public sphere—robs people of courage, of the strength of heart to do what deep down they believe to be right [1989, p. 2].

If we choose to banish moral discourse and leave managers to face ethical issues alone, we invite dreary and brutish political dynamics. An organization can and should take a moral stance. It can make its values clear, hold employees accountable, and validate the need for dialogue about ethical choices. Positive politics without an ethical framework and moral dialogue is as unlikely as bountiful harvests without sunlight or water.

The question is not whether organizations are political but what kind of politics they will encompass. Political dynamics can be sordid and destructive. But politics can also be a vehicle for achieving noble purposes. Organizational change and effectiveness depend on managers' political skills. Constructive politicians know how to fashion an agenda, map the political terrain, create a network of support, and negotiate with both allies and adversaries. In the process, they will encounter a predictable and inescapable ethical dilemma: when to adopt an open, collaborative strategy or when to choose a tougher, more adversarial approach. In making the decision, they have to consider the potential for collaboration, the importance of long-term relationships, and, most important, their own values and ethical principles.