© Joy Absalon

We live in a litigious society, like it or not. People want to protect what they have, and on occasion this goes beyond what is prudent or even reasonable. Nonetheless, photographers must work within the confines of legality and must not only protect their work but also protect to the rights of others. Because a photograph is so potentially revealing, it has a special place in the legal world, and in the wrong hands, it can be very damaging.

Sports photographers must be aware of legal issues in their efforts to ensure that they are protecting the rights of others as well as themselves. In addition, especially because their work takes place almost exclusively in the field, they must be prepared for the legal restrictions placed upon them by the organizations and individuals they encounter and with whom they work.

Some people love having their photos taken, and others — especially in light of how broadly images can bedisseminated on the Web — are highly concerned and suspicious of their images appearing without their permission or knowledge. Every photography situation differs in its legal implications, and this aspect of amateur as well as professional work must be realized and kept in mind.

This said, I'm a photographer and not a lawyer. I do everything I can to protect myself and adhere to the legal restrictions placed on me in various situations and by various organizations. In this chapter, I offer some guidance and advice based on the law and standard practices, as I understand them. You should do the same; the more public your images, the more you should protect yourself as well as your subjects, and if necessary you should consult with an attorney to ensure that you're doing the right thing.

Note

For a really great and thorough source of helpful legal information for photographers, check out Law in Plain English for Photographers by Leonard D. DuBoff. This covers a wide range of legal issues that you will find useful.

As part of working on this book, I set out to take some soccer photos. I contacted the state soccer organization, which, as it turned out, was having a state youth championship. I applied to them as a media photographer, telling them I was looking for images for my book on sports photography.

For the championship, the state organization required that I submit a written request to them as a member of the media, to send them a photograph of myself, and to fill out a state patrol document indicating whether I had been convicted of any felony. Further, I had to include my name, address, phone number, social security number, and driver's license number.

Once approved, they sent me a media credential in the mail — a badge to wear at the event — as well as an e-mail confirmation I also received a card in the mail for my state patrol approval The state organization was very friendly and seemed pleased that I was attending.

When I went to the event, which perhaps had about 100 spectators, I was the only photographer aside from the company taking professional shots and selling them (which I was not doing) I approached the organizers and let them know I was there. The state commissioner introduced himself and immediately told me that no one had told him I was coming, and he seemed surprised. I explained what I was doing.

We discussed that I wanted to take shots of soccer players (in this case, 17- and 18 year-old girls) playing at this state final to publish in a book. I also indicated that I would probably like to get model releases from individuals who might appear in the book.

The commissioner immediately expressed concern about this, and to make a rather long story a bit shorter, told me that I would have to go through the state organization to contact the teams, and then the teams would have to contact the parents of the athletes, and that it could be a very long, drawn-out process.

In addition, the commissioner told me that he was limiting me to taking images from no closer than wherever the spectators were sitting and standing — at least 30 yards from the field — and that the closer spots on the huge and wide-open spaces surrounding the field were limited to the commercial photographers shooting the event.

"Your legal limitations here are more rigid than the Olympic Games," I told him "Yes, we like to keep a very sterile environment," he replied Figures 13-1 and 13-1 illustrate how I made the most of a restrictive situation by taking shots that show the soccer game from perspectives that do not reveal any specific players personally.

If you decide you want to try to get media credentials for an event, make sure to ask what allowances it gives you and if officials will be notified of your attendance ahead of time. However, even if you do all this, you still aren't guaranteed the best access or great shots.

Every organization is responsible for protecting its youth players while they play in very public places, ranging from their safety on the field to who has access to them. But, you have to protect yourself, so work with your chosen organization as best you can and follow the rules they've set.

Sports photographers must understand legal limitations and what's asked of them in any setting. You may be taking a photograph of an individual skateboarder, a catcher and batter at a Little League baseball game, a parasailer soaring above the trees, or players from two basketball rivals playing against each other on a court. Each of these situations presents different legal scenarios, and you should know what to do for each.

Figure 13-1. To avoid significant hassles in getting permissions, I chose to take some photos that had a larger scope in which no athlete could be recognized.

Figure 13-2. Shots of the action going away, where subjects are not facing you, are also a good work around.

Furthermore, each situation differs depending on what you intend to do with the photos. If you're publishing the photos in your personal Web gallery, that's much different than just showing them in a slide show in your living room. If they're going to be published somewhere, or you're going to sell them, you're again dealing with different legal issues.

Let's say that you take a photo of a nice couple sitting in the stands of a hockey game, and you publish the image on your public Web site all about ice hockey. Have you violated the couple's right to privacy?

Most right-to-privacy laws focus on photographs of individuals "in seclusion," not at a public event However, singling out a non-performing subject at a sports event, such as a screaming fan, and publicizing it may potentially present a case that you've infringed on their right to privacy. If possible, you should get that person's written permission to use his photo for anything other than private use. This applies doubly if the subject is a minor.

Our commissioner friend, while making the media photographer's life difficult and preventing his sport from being better publicized, certainly had the protection of young soccer players in mind. Kids represent a special category in the law, and those who come into contact with them — whether as a coach, a parent driving someone else's children, a referee, or a sports photographer — become responsible for protecting and respecting them individually and collectively. Their protection is (or at least should be) more important than anything else. At the same time, everyone has a job to do.

If you're a parent shooting your child while he or she competes on a playing field and other kids are in the photo, especially at an event open to the public, there's no problem if you print these images, give them to friends, and even put them on the Web to share with others on a service like Kodak Image Gallery or Snapfish. You're not publishing the images commercially, and the event was taking place where anyone could come and take photos.

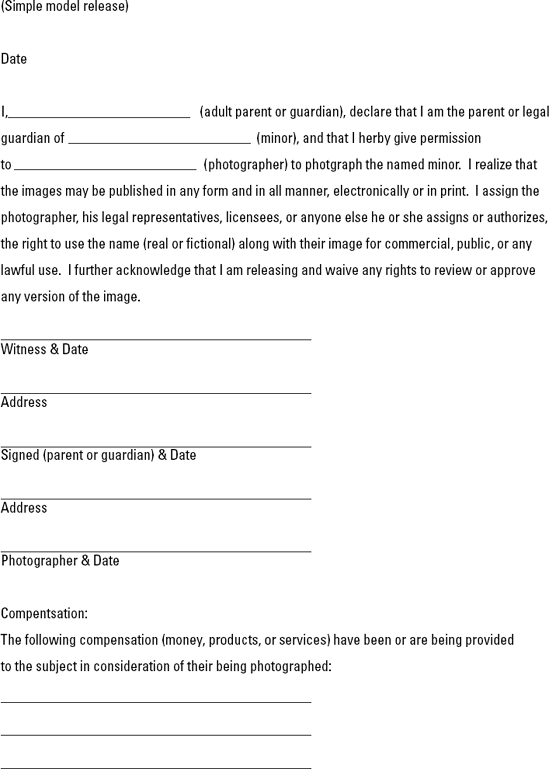

However, this gets a little different if you've singled out a particular player — presumably not your own child — and taken several photos of her and then published the images on your own without a particular reason to do so. Even if that child was the leading scorer in the game, when you're taking kids' photos for any kind of publication, it's best to get written permission in the form of a model release, from someone in authority — at the least, a coach or organizer, but it would be best to have a parent's or guardian's signature. If you plan to use the images on your Web site, or have them displayed publicly (such as in a photo presented in a gallery), or used commercially — such as in a magazine ad — you must get a release. If the player is being compensated for having his photo taken, then that should also be stated in the release and the amount/type of compensation specified.

If the players are not recognizable — meaning that you can't see their faces or something else that obviously identifies them (like a name on a shirt), then no release is necessary Figure 13-3, for example, shows some soccer players' feet on the field; even if these players recognize themselves in the image, there is no legal issue with the image because no one will know who they are.

Tip

In some cases, players and those responsible for them — their parents, typically — sign a publicity and photo release before an event as part of their registration. If so, the organization can tell you that this is the case if you are working for the organization or if you are going to use the images for media or other purposes. However, this usually does not include commercial usage.

Many sports organizations are very intent upon protecting their images. Typically, in a photo of a large, public sports scene where many players are visible but appear only as a small part of the shot, concern about using the image at the individual player level is minimal. Using it as a fine art image — such as in an art gallery, on a Web gallery, or in a similar fashion — may be acceptable and of little consequence. However, the organization putting on the event or the teams themselves may not approve of the photo being used for commercial purposes, which means that you are using it to promote something such as a product or a company; selling the image(s) as fine art or as stock, generic shots are distinguished from this use.

Figure 13-3. No one can tell who these soccer players are, where they are, or even what team they're on, so there's no legal issue with them being used commercially or publicly. Additionally, this image has been treated creatively with the Photoshop Cutout filter for an interesting effect.: © Alexander A. Timacheff

If you've engaged the organization or team to shoot the players and to sell them team and/or player photos, then you're in a different situation Presumably, everyone coming to have her photo taken knows the images will be printed and probably used on a public Web gallery or in some other way Some Web services offer the option of having the photos password-protected, which is something you may want to offer parents. You don't need a release for this kind of photography because it's a personal service and everyone is giving you implied permission to take the photos by being there for the shoot. If you decide some of the images from the shoot are ones that you'd like to use to promote your business, however, such as on your Web site or in a brochure, then you should get a parental release And, obviously, if you intend to sell the image to another entity such as for stock or commercial purposes, then you definitely need a release.

With adult athletes, the same general rules apply as with youth sports:

For images where no one is recognizable, you don't need a release.

Know and respect the organization's and the teams' legal restrictions.

If you're taking photos for any purpose other than as a family member or friend, let the organization know you're there and what you're doing.

Images just for your own private use don't require any special permission (usually, unless someone notices you taking photos of them and objects to having photos taken).

Using an image for the media, as fine art, or commercially are legally different, and each situation may require you to do different things, such as obtaining a model release.

If in doubt, get a model release (obviously, the athlete and/or subject can sign it himself).

Model releases are most often meant to protect the photographer. They allow you to do whatever you need to do with a photo and indicate that the subject (as well as the parents or guardians, if the subject is a minor) has given you unrestricted permission to use and own the photos you take of them.

Not everyone, of course, is willing to sign a model release. Every photographer has encountered — or will encounter — situations where a great shot can be or has been taken and the subject refuses to allow it to be used. In these situations, you can do little to get someone to sign a release if he's not happy about his image being displayed somewhere. Furthermore, even if the image could arguably be used without a release, if you know the person may have a problem with it, it's probably not worth the risk.

The bottom line in youth as well as adult sports photography is that getting a release is often desirable and sometimes a necessity Figure 13-4 shows a typical, simple release that you can use for these purposes.

You should keep signed model releases in a safe and accessible place where you can get to them if it ever becomes an issue I hope it won't.

As a sports photographer, you probably don't want to use lengthy, jargon-ridden model releases to distribute at sports events. If you're doing a commercial shoot with models for a specific client, that's a different story. But if you want to be able to use images on your Web site, for fine art, or other less commercial endeavors, simple releases work because they are plain, clear, short, and still legally binding. A person in the midst of a sporting event — whether a player or a spectator — is far more likely to sign a short, simple release.

Whether it's a local Little League team or an NFL giant, every structured sports organization has a concern for how its team is portrayed in photographs. Although some large organizations, such as Major League Baseball or the National Hockey League, may, along with various stadiums, limit you just as a spectator in what kinds of photos you may or may not take, you can easily attend most sports events and shoot photos for your own use. You can even share images on Ofoto or another service without concern.

However, if you plan to publish, sell, or use the images in any commercial way, or sell or even give them to a media organization, then most teams require that you get their permission to do so. Fortunately, it's easy to get credentials for the vast majority of sports events other than the big professional ones, because most teams and organizations want as much publicity as possible.

Another limitation that is important to consider is that of the school sports organizations, and, in particular, the NCAA Responsible for managing collegiate athletics, the NCAA is very restrictive when it comes to maintaining the amateur standing of their athletes. They cannot receive compensation of any kind for photos taken of them, and photographers are discouraged from using the photos unless they're officially sanctioned and credentialed by the NCAA or are members of a recognized media organization.

If you're attending a game and you want some photos of your favorite player, or family member, there's no issue However, if the photos are used in any other way, then the college will want to apply its limitations in accordance with how it interprets NCAA regulations; not doing so can potentially cost the college as well as individual athletes the eligibility to compete in NCAA events —or to be fined.

For example, you may have heard the story of a college athlete at one U.S. university who was banned from competition for a period of time because he allowed a sorority at his school to use his photograph in a fundraising calendar. Although he received no compensation for the image, it was still considered a violation.

There's a distinction made between how you intend to use the images: to sell them commercially and publicly (such as for stock or specific advertising purposes); to sell them to the media (for publication in a news-oriented newspaper, magazine, or Web site); or for private use (such as fine art and individual ownership of the image). Various sports entities sometimes stipulate how you can use your images based upon these different uses and will give you credentials accordingly.

A tremendous amount of personal photography was shot at the Olympic Games, and a Kodak photo center on-site allowed spectators to develop, process, and print their film and digital photos, but anything commercial was restricted. The International Olympic Committee goes to great lengths to protect its image in many ways, and photography is one of them.

In an official capacity at the Olympics, I was subject to a commercial usage limitation, meaning that my photography was to be used for media and private use only. Also, because official photographers get special access to areas where others cannot enter, they must have special security credentials Months before the games, I had to apply using a detailed process and set of forms. It doesn't matter if it is the Olympics or the local soccer tournament, some form of credentials may be needed.

Other big sports organizations, such as major-league sports, also greatly limit and usually completely prohibit any commercial photography that they haven't commissioned Media photographers get special credentials through their publications or news/sports bureaus, and getting a media pass isn't easy Space is limited on the sidelines (see Figure 13-5) and in the photographer areas, so even the qualified photographers have a pecking order.

Figure 13-5. All of the photographers on the sidelines of this pro football game have obtained media credentials well in advance of the game.: © Terrell Lloyd

For any sports organization beyond a small, local team, and for any photography other than for your own private use, you should contact the organizers ahead of time to get credentials for the event — or, at the very least, to let them know you'll be there and learn about any limitations they may have. By contacting the organization, you may get special access; the organization probably wants to have its event photographed and may go out its way to provide you with the opportunity to take some really great shots.

Copying pictures has never been easier. A digital photograph on the Web is vulnerable to being duplicated with a couple of mouse clicks, and it can instantly be sent anywhere in the world to be used in a manner over which the photographer has no control or knowledge. So, you must protect your work.

A photograph I took of a jumping fencer from the Olympic games has become so popular that I often hear that it has been taken and used — even though the only copies that I provided were watermarked, meaning that that they have added text and/or graphics displayed as part of the image. At a recent fencing championship in Tokyo, a referee told me that his brother was using the image as a background screen for his mobile phone!

My knowing about it or having no control over what happens doesn't make it any more legal, of course When you take a photograph, you own it, unless you're doing it on assignment for an organization and you've given permission for the organization to own the photos You don't have to apply to the federal government to lay claim to owning the image, although there is a way to file images with the U.S. Copyright Office (there is a fee, so it can be pricey if you have lots of images).

You can put your name, a copyright statement, and other personal information into the metadata of an individual image (the embedded information in an individual digital image, which shows camera and exposure information automatically as well as information you can add), which at the very least identifies you as the originator of the image. Figure 13-6 shows metadata being added to a photo in Photoshop Elements. If you haven't added your own information to the metadata tag, someone else can put his name in it and claim it for his own — sort of a "finders-keepers" concept of digital photography, but a disturbing one. Many image-editing packages let you add metadata tags to large numbers of photos in a batch process, which is an advisable thing to do if your images are getting passed around digitally. Metadata isn't necessarily permanent, however, other than the camera/exposure information, which you can't easily change. Theoretically, someone could go into a file and change the information — so it's merely a deterrent, not a definitive way of preventing the file from being misused.

To see the metadata, and to add your own, in Photoshop Elements, open a photo, such as a JPEG or TIFF file. Once the image is open, choose File

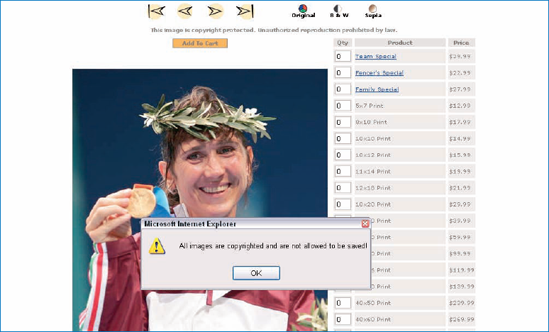

Images that appear in photo-sharing and storefront services are often in danger of being copied as well, unless the company has protected them through software (if you right-click on an image in Printroom com, for example, instead of seeing a menu with the option to copy, a dialog box appears telling you the image is copy protected, as shown in Figure 13-7).

Another way to protect images is by watermarking them Removing the watermark would irreparably damage the photo Some online services offer this as an option All stock agencies watermark their photos, and various image-editing packages allow it as well. Another way to do it is to add text across an image in your image-editing package — your name, for example — and then save the image as a flattened JPEG file. When you flatten an image, you remove the separate layers of text and the image; all the elements are merged as one layer, as demonstrated in Figure 13-8. You can then put this image on your Web site or offer for distribution, unless it's specifically destined for final display.

Tip

If you watermark an image yourself, don't just place the watermark in a small corner of the photo. Someone could still crop out the watermark and use the photo without it!

Yet another way of protecting images has to do with prints. Many professional photographers use back printing on prints, which means that their studio and/or personal information is printed on the back of the photograph by the lab. If you're using a lab or an online service, you can ask whether this is an option; usually it's offered for free or for a small fee per image. If someone were to take that print to another lab and ask that it be scanned and copied, most professional labs will refuse to do so if they see a copyright statement or even a photographer's name.

Tip

If you're selling your work, many people will want to buy digital photos from you, and not just prints Some photographers won't sell digital images; if you decide that you will, make sure that you have metadata tags on the images and don't sell the full-sized images unless the customer has paid a price for them that reflects their value — remember, once they have the digital images, chances are you won't be selling them prints of the image! Also, organizations such as the Professional Photographers of America offer small copyright leaflets that you can include with your order.

The very nature of digital photography demands that you do everything you can to prevent your images from being copied; if you're reasonably prolific and you've distributed your photos to others, it's likely that you'll encounter copying at some point. The best defense is a good offense, as they say, so do whatever you can to prevent problems It's much easier than fixing problems after they happen.

Sports photographers of all types must understand the legal implications of digital photography Shooting at sports events often requires letting the organizers know that you're there, and they may require you to have some credentials or be pre-approved to photograph the event. Other photographers may have contractual arrangements allowing them to be there, and if you appear to be a commercial threat to them, you'll hear about it. Getting permission from event organizers is important and may require that you sign documents; however, this may give you access to being able to take photographs from angles you may not otherwise have had.

If you're shooting images that will end up in print or on the Web — especially in any commercial or highly visible way — then you need to get model releases from your subjects. This becomes increasingly important when it involves minors, and then you'll need to involve parents or guardians. The basic rule: If in doubt, get a release.

Protecting your work is the flip side of the legal issue in photography. Your images are your personal property, and you should know how and when to have them watermarked, as well as how to add metadata that helps identify them as yours. Although it's probably impossible to completely protect your work from others taking it — and the more visible and interesting your work is, the more likely it is to be taken — you can take measures to prevent it.