Optimism built on optimism to drive prices up. Then came the crash and the eventual discovery of the severe mental and moral deficiencies of those once thought endowed with genius and their consignment, at best, to oblivion, but, more grimly, to public obloquy, jail, or suicide.

The Great Depression began in October 1929 with the U.S. stock market crash and quickly became a severe worldwide economic contraction.[182] Before the Great Crash, however, a significant boom and bust sequence took place in Florida, one that revealed the speculative tendencies of the time. In this chapter, we'll discuss the Florida land boom that took place during the mid-1920s and the rapid ascent of the stock market in the late 1920s before evaluating the events via the five lenses presented in Part I of the book.

The great Florida real estate bubble of the 1920s was a revelatory manifestation of the speculative tendencies that were sweeping through America following World War I. Confidence was running high, and by the mid 1920s, an unsustainable boom in Florida land was underway. In fact, to many, the rapid boom and bust of Florida real estate was thought to be like castles built in sand. It only took high tide to wash them away. One of the most prominent developers of the times, Carl Graham Fisher, was also a promoter of the Indy 500 and helped create some of the first transcontinental roads. Fisher was one of the primary reasons that Florida transformed into the hottest market during a great bull market. Fisher successfully converted portions of South Florida into a heavenly combination of golf, polo, deep sea fishing, luxury hotels, and glamour.

Although property fever spread throughout Florida, migrating up the state's east coast and west coast, Miami represented ground zero of the speculative tendency. Consider the following passage from a chapter titled "Home, Sweet Florida" in the book Only Yesterday, written in 1931:

There was nothing languorous about the atmosphere of tropical Miami during the memorable summer and autumn of 1925. Miami had become one frenzied real estate exchange. There were said to be 2,000 real estate offices and 25,000 agents marketing house-lots or acreage.... The city fathers had been forced to pass an ordinance forbidding the sale of property in the street, or even the showing of a map, to prevent inordinate traffic congestion.... A traveler caught in a traffic jam counted the license-plates of eighteen states among the sedans and flivvers waiting in line. Hotels were overcrowded. People were sleeping wherever they could lay their heads, in station waiting-rooms or in automobiles. The railroads had been forced to place an embargo on imperishable freight in order to avert the danger of famine; building materials were now being imported by water and the harbor bristled with shipping. Fresh vegetables were a rarity, the public utilities of the city were trying desperately to meet the suddenly multiplied demand for electricity and gas and telephone service, and there were recurrent shortages of ice.[183]

Not exactly a description of sparsely attended Sunday afternoon open houses in suburban settings! As the description reveals, there was an intense flurry of activity that had drawn many from near and far and swirled them into a speculative frenzy. The other prevalent component of the times was the effective use of leverage via the 10 percent down payments made to "buy" land. This facilitated sales and postponed the tiresome formalities of recording deeds, etc. An executive of the Retail Credit Company of Atlanta described the sales process quite succinctly:

Lots are bought from blueprints, they look better that way.... Reservations are accepted. This requires a check for 10 per cent of the price of the lot the buyer expects to select. On the first day of sale, at the promoter's office in town, the reservations are called out in order, and the buyer steps up and, from a beautifully drawn blueprint, with lots of dimensions and prices clearly shown, selects a lot or lots, get a receipt in the form of a "binder" describing it, and has the thrill of seeing "SOLD" stamped on the blue-lined square which represents his lot, a space usually fifty by a hundred feet of Florida soil or swamp.[184]

Allen continues his description of the speculative frenzy, noting that few actually intended to purchase the land:

The binder, of course, did not complete the transaction. But few people worried much about the further payments which were to come. Nine buyers out of ten bought their lots with only one idea, to resell, and hoped to pass along their binders to other people at a neat profit before even the first payment fell due at the end of thirty days.[185]

Allen cites seven primary causes for the speculative land boom that took place in Florida during the mid-1920s: (1) the climate, (2) accessibility to the populous northeast United States, (3) the automobile, which Allen notes "was making America into a nation of nomads, teaching all manner of men and women to explore their country..." (4) abounding national confidence inspired by years of economic prosperity under the Coolidge administration, (5) the backlash against "the very routine and smoke and congestion and twentieth century standardization of living" that created a desire for country club living, (6) the success of Southern California's resort-image developments, and (7) the belief that Florida offered a chance to develop sudden wealth (i.e., one could get rich quick!).

Eventually, however, the greater fools stopped showing up and the boom turned into a bust. The land boom began to collapse during the late spring and summer of 1926 when binder-holders began defaulting on the payments they were supposed to make. Rapp notes how the embedded leverage combined with other developments, including two hurricanes, to put the finishing touches on the bust:

Many of those with paper profits found that the properties they owned were preceded by a series of purchases and sales, all at 10% down, and as many of these defaulted, the only options were to either hold onto the land at a great loss, or default. The land was often burdened with taxes and assessments that amounted to more than the cash received for it, and much of the land was blighted with a partly constructed development. As the deflation expanded, two hurricanes added the finishing touches to the bursting bubble. The hurricanes left four hundred dead, sixty-three hundred injured, and fifty thousand homeless.[186]

Following the bust, Henry Villard described the images he saw as he drove into Miami in The Nation:

Dead subdivisions line the highway, their pompous names half-obliterated on crumbling stucco gates. Lonely white-way lights stand guard over miles of cement sidewalks, where grass and palmetto take the place of homes that were to be.... Whole sections of outlying subdivisions are composed of unoccupied houses, past which one speeds on broad thoroughfares as if traversing a city in the grip of death.[187]

Allen highlights the economic impact on Miami by citing bank clearings data (see Table 7.1). After rising steadily during the early 1920s and crossing $1bn in 1925, bank clearings steadily fell.

Table 7.1. Miami Bank Clearings

Year | Bank Clearings |

|---|---|

1925 | $1,066,528,000 |

1926 | $632,867,000 |

1927 | $260,039,000 |

1928 | $143,364,000 |

1929 | $142,316,000 |

Noting that this economic distress took place during "the very years when elsewhere in the country prosperity was triumphant," Allen eloquently summarizes the Florida land bust: "Most of the millions piled up in paper profits had melted away, many of the millions sunk in developments had been sunk for good and all, the vast inverted pyramid of credit had toppled to earth, and the lesson of the economic falsity of a scheme of land values based upon grandiose plans, preposterous expectations, and hot air had been taught in a long agony of deflation."[188]

It is impossible to understand the Great Depression without understanding the Roaring Twenties. The economic boom of the 1920s is perhaps as significant a development in the history of booms as the Great Depression is in the history of busts. While lots of attention has been given to the Great Depression, it seems unlikely that it would have been as significant without the less-addressed boom of the 1920s.

There are numerous factors that help explain the 1920s boom. To begin, not unlike the Dutch military successes, the United States and its allies had just won the First World War, and not unlike the Dutch following their victory over Spain, American confidence was running high. WWI had helped the country accelerate its transition from an agricultural economy to an industrial nation. The Federal Reserve system, which had been created in 1913, was seen by many as the solution to the business cycle problem (i.e., the Federal Reserve would be able to steer the economy with such precision that booms, busts, and blowups would never again occur).

Mass production had been gaining prominence and reduced the costs of many goods, productivity soared[189] while unit costs sank, and several industries appeared poised to change the world. In particular, cars and radios were the "new thing" of the day, and there seemed to be limitless demand for these goods. Automobiles were increasingly commonplace, and by the 1920s, more than 50 percent of Americans owned cars.[190] Transportation was being revolutionized, and trains and cars provided the means for domestic commerce to boom with increasingly lower frictional costs. Taxes were low, consumer optimism ran high, and electricity distribution was now so widespread that most Americans were "on the grid." Most industries (agriculture being a primary exception) were booming as consumption and investment were supported by a massive tailwind of hope and optimism.

According to John Kenneth Galbraith, the real economic gains in the 1925–1929 period were substantial. GNP was up 13 percent in five years, auto production was up 23 percent in three years, industrial production was up 64 percent in seven years. He says, "Throughout the twenties, production and productivity per worker in manufacturing industries increased by about 43 percent. Wages, salaries, and prices all remained relatively stable."[191]

Although economic progress was indeed substantial and based on genuine increases in productivity, asset prices—specifically, the stock market—eagerly reflected these developments and likely more. It is hard to know when exactly the stock market began to distance itself from the extraordinary fundamental developments and entered the realm of speculative excess, but Galbraith eloquently notes that "early in 1928, the nature of the boom changed. The mass escape into make-believe, so much a part of the true speculative orgy, started in earnest.... The time had come, as in all periods of speculation, when men sought not to be persuaded of the reality of things but to find excuses for escaping into the new world of fantasy."[192]

Galbraith goes on to note how the market's quiet winter months of 1928 were followed by stock prices rising "not by slow, steady steps, but by great vaulting leaps."[193] Figure 7.1 demonstrates the magnitude of the leaps by plotting the real S&P Composite Index divided by the 10-year moving average of real earnings. By using inflation-adjusted numbers and a 10-year earnings period, the data measure how expensive the market is relative to corporate profit-generating abilities and is not subject to single year surges (or depressions) in profits. Note the chart goes back to 1881 and stops in October 1929, right before the market crash.

Lest you think that the index was the only manifestation of the market's upward jaunt, Table 7.2 summarizes the movement in share price of 12 very popular and widely held stocks between March 3, 1928 and September 3, 1929.

The beginning of the economic bust is widely believed to be the October 1929 crash of the stock market. Although most students of the Great Depression focus on the events of Tuesday, October 29, 1929, much can be learned by studying the three prior trading sessions—back to and including the prior Thursday.

Figure 7.1. Real S&P Composite Index as a Multiple of 10-Year Moving Average Earnings, January 1881–October 1929 Source: Robert Shiller. Data accessed via www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data

Table 7.2. The Big Bull Market

Company | Opening Price (3/3/28) | High Price[a] (9/3/29) | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

Source: Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1931). | |||

American Can | 77 | 181 7/8 | 136.2% |

AT&T | 179 7/2 | 335 5/8 | 86.9% |

Anaconda Copper | 54 1/2 | 162 | 197.3% |

Electric Bond & Share | 89 3/4 | 203 5/8 | 126.9% |

General Electric | 128 3/4 | 396 3/4 | 208.2% |

Montgomery Ward | 132 3/4 | 466 1/2 | 251.4% |

New York Central | 160 1/2 | 256 | 59.5% |

Radio (RCA) | 94 1/2 | 505 | 434.4% |

Union Carbide | 145 | 413 5/8 | 185.3% |

US Steel | 138 1/8 | 279 1/8 | 102.1% |

Westinghouse | 91 5/8 | 313 | 241.6% |

Woolworth | 180 3/4 | 251 | 38.9% |

[a] Adjusted to reflect the effects of stock splits and rights issues. | |||

On Black Thursday, as October 24, 1929 has since been known, the market entered a serious state of panic—with no immediate or palpable cause. Historian Edward Chancellor notes, "Unlike former stock market panics, it was not preceded by tightness in the money market. No banking, brokerage, or industrial failures served as a trigger—and yet panic there was."[194] Many stocks were dropping more than several percentage points between trades, and the market appeared to be in the midst of a complete meltdown—until calm was restored by JP Morgan and others who jointly entered the market and began publicly buying to support share prices. By the end of the day, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had recovered most of its losses and closed down 6 points to 299. Nearly 13 million shares had been traded on the NYSE, which was almost triple the "normal" volume.

Friday was a relatively calm day, and many brokers worked through the weekend to catch up on trades and to calculate margin calls that needed to be sent out to clients. The market fell 38 points to 260 on Monday, and by Tuesday, the market was in complete panic. Chancellor describes the events as follows: "On the floor of the Stock Exchange, a broker grabbed a messenger by his hair, another fled the floor screaming like a madman, jackets were torn, collars dislodged, and clerks in their frenzy lashed out at each other..... On Black Tuesday, the glamour stocks of the bull market suffered the worst damage."[195] Table 7.3 summarizes the magnitude of the one-day fall among these glamour stocks.

The slide into depression that followed the stock market crash was likely caused by numerous factors, including (but definitely not limited to) the presence of bank failures[196], "sticky wages,"[197] adherence to the gold standard[198], the unsustainable growth of consumer credit,[199] and high leverage levels among consumers, corporations and other organizations.[200]

Allen cites seven economic diseases that plagued businesses around the world and contributed to the conversion of the Great Crash in America into the global Great Depression: (1) overproduction of capital and goods, (2) artificial commodity prices, (3) collapse of silver prices and the corresponding drop in purchasing power of Asian consumers, (4) the international financial derangement caused by the shifting of gold to France and the United States, (5) unrest in foreign countries, (6) the self-generating and vicious feedback loops of confidence that affected the economy, and (7) "the profound psychological reaction from the exuberance of 1929" and corresponding destruction of consumer and corporate confidence.

The full impact of the Great Depression that followed the stock market crash of 1929 is hard to understand for Americans born and raised following the end of World War II. Robert Samuelson summarized the massive impact it had on the American economy, the world economy, and the world that emerged after the Great Depression:

The Great Depression of the thirties remains the most important economic event in American history. It caused enormous hardship for tens of millions of people and the failure of a large fraction of the nation's banks, businesses, and farms. It transformed national politics by vastly expanding government, which was increasingly expected to stabilize the economy and to prevent suffering. Democrats became the majority party. In 1929 the Republicans controlled the White House and Congress. By 1933, the Democrats had the presidency and, with huge margins, Congress (310–117 in the House, and 60–35 in the Senate). President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal gave birth to the American version of the welfare state. Social Security, unemployment insurance, and federal family assistance all began in the thirties.

It is hard for those who did not live through it to grasp the full force of the worldwide depression. Between 1930 and 1939 U.S. unemployment averaged 18.2 percent. The economy's output of goods and services (gross national product) declined 30 percent between 1929 and 1933 and recovered to the 1929 level only in 1939. Prices of almost everything (farm products, raw materials, industrial goods, stocks) fell dramatically. Farm prices, for instance, dropped 51 percent from 1929 to 1933. World trade shriveled: between 1929 and 1933 it shrank 65 percent in dollar value and 25 percent in unit volume. Most nations suffered. In 1932 Britain's unemployment was 17.6 percent. Germany's depression hastened the rise of Hitler and, thereby, contributed to World War II.[201]

Applying the five disciplinary lenses developed in Part I of the book proves fruitful in trying to understand the 1920s and 1930s from a bubble-spotting perspective. Let us now begin by evaluating the (lack of) equilibrium tendencies during the Florida real estate boom and the Roaring Twenties, as well as the subsequent Great Depression.

How is it that individuals and institutions that found it logical and rational to pay one price for a security one day would not be willing to pay 50 percent of that price the next day? Surely, such developments do not occur in a totally "efficient" market. In fact, the tendency toward equilibrium is one of the major tenets of microeconomics that seems to have broken down during both the booming 1920s and the busted 1930s.

The procyclical nature of leverage enabled consumers to buy more during good times as credit was easily obtained in a rising market. Financial innovations such as installment purchases (i.e., buy now, pay later) effectively increased consumer demand as the market boomed. When such credit contracted, not only did such credit-fueled buying slow, but so too did normal buying demand disappear as it had been "brought forward" into the 1920s by access to this credit.

Perhaps the most obvious example of the self-reinforcing nature of the times is found in Florida. Allen captures the essence of the dynamic quite eloquently in describing the fate of an individual who experienced both the boom and bust as well as the accompanying joy and pain: "One man who had sold acreage early in 1925 for twelve dollars an acre, and had cursed himself for his situation when it was resold later in the year for seventeen dollars, and then thirty dollars, and finally sixty dollars an acre, was surprised a year or two afterward to find that the entire series of subsequent purchases was in default, that he could not recover the money still due him, and that his only redress was to take his land back again."[202] Thus, just as higher prices induced more buyers, so too did lower prices generate more sellers. Not surprisingly, this dynamic generally failed to produce an equilibrium.

The economic bust that followed the Great Crash had a very reflexive component to it, with a very self-reinforcing element to the dynamics of business during the 1930s. As described in Only Yesterday, "each bankruptcy, each suspension of payments, and each reduction of operating schedules affected other concerns, until it seemed almost as if the business world were a set of tenpins ready to knock one another over as they fell; each employee thrown out of work decreased the potential buying power of the country."[203] Again, the snowballing effect here seems to resemble a reflexive dynamic connected by confidence.

Recall that one of the primary beliefs of the Austrian school of economics is that inappropriately cheap money results in malinvestment and overcapacity, which must be "cured" via capital destruction, deflation, and a general working-through of the excesses. Austrian economists believe that the meddling of central banks in setting the price of money distorts the economy and exacerbates the likelihood of booms and busts. Could this criticism be applied to the Great Depression? What role did the price of money play during the 1920s and 1930s?

According to Chancellor, "The Federal Reserve in Washington—the institution that had supposedly abolished panics—had inadvertently ignited the stock market boom by lowering rates in 1925." This was explicitly intended to help Britain manage the accelerating outflows of gold after their return to the prewar gold standard. Although this action might have been useful to the Brits, it had an extraordinary effect (i.e., increasing it) on the American appetite for risk.

Although such low-priced money found its way into increased corporate capital expenditures and increased consumer purchasing of both durable and consumable goods, one of its most powerful outlets was via margin loans used to enable the purchase of additional securities. Margin loans, which enable the purchase of financial securities with borrowed money, had grown concomitantly with the stock market's climb. By October 1928, credit extended by banks, brokerage firms, and other financing sources to investors had risen to nearly $16 billion, which equated to approximately 18 percent of the total stock market capitalization of the entire market.[204]

If inappropriately low rates had created the boom that manifested itself most evidently in the stock market, might more "normal" but higher rates be responsible for the bust that immediately followed the Great Crash? According to Shiller, "On February 14, 1929, the Federal Reserve Board raised the rediscount rate from 5 percent to 6 percent for the ostensible purpose of checking speculation. In the 1930s, the Fed continued the tight monetary policy and saw the initial stock market downturn evolve into the deepest stock market decline ever, and a recession into the most serious U.S. depression ever."[205]

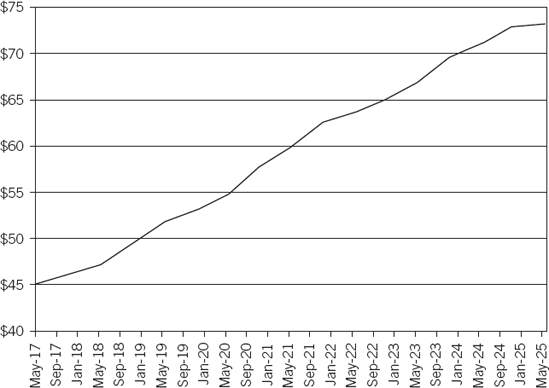

Perhaps the supply of money might help account for the boom–bust sequence. Figure 7.2 summarizes total money supply from June 1921 through June 1929. Might some of this money have found its way into asset markets?

Although it is very difficult to establish causality, it does appear that money supply was correlated with asset prices. These procyclical liquidity conditions likely exacerbated underlying boom and bust tendencies as asset prices correlated with the money supply.

The psychological state of market participants during the 1920s was characterized by optimism and confidence inspired by self-reinforcing virtuous market developments. Might some of this optimism and confidence have translated into a sense of overconfidence and investor invincibility? Consider the following passage from Only Yesterday:

As people in the summer of 1929 looked back for precedents, they were comforted by the recollection that every crash of the past few years had been followed by a recovery, and that every recovery had ultimately brought prices to a new high point. Two steps up, one step down, two steps up again—that was how the market went. If you sold, you had only to wait for the next crash (they came every few months) and buy in again. And there was really no reason to sell at all: you were bound to win in the end if your stock was sound. The really wise man, it appeared, was he who 'bought and held on.'[206]

Figure 7.2. Total Money Supply during the 1920s Source: Murray Rothbard, America's Great Depression (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000) Table 1, 92.

"New era" thinking was clearly present, as noted by the prominent emergence of the automobile and radio industries. Aerospace and movie production played supporting roles among investors' foci. The automobile soon replaced the railroads as the engine of commerce and "it transformed the culture and geography of the nation; roads were surfaced, highways built, and garages erected to accommodate the increasing number of passenger cars, which rose from seven million to twenty-three million during the 1920s."[207] Not surprisingly in this climate, General Motors' share price increased by more than 10 times between 1925 and 1928.

The radio, launched by Westinghouse in 1920, also began to fascinate the investor with unlimited possibilities of information dissemination. The industry was dominated by Radio Corporation of America (RCA), often referred to by investors of the time as "Radio." Known as the "General Motors of the Air" by investors,[208] Radio climbed from under $2 per share in 1921 to over $110 by 1929. In 1929, it was the most heavily traded stock on the New York Stock Exchange.

Aerospace also provided a believability to the new era thinking of the times, spurred in large part by Charles Lindbergh's solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927, and the replacement of silent movies with "talkies" captured investor imagination.

The vision of the future held by most Americans in 1929 was one of unbridled optimism, a vision that likely generated and validated the (over)confidence that permeated investor sentiment. In describing the average American, Allen said he

visioned an America set free from poverty and toil. He saw a magical order built on the new science and new prosperity: roads swarming with millions upon millions of automobiles, airplanes darkening the skies, lines of high-tension wire carrying from hilltop to hilltop the power to give life to a thousand labor-saving machines, skyscrapers thrusting above one-time villages, vast cities rising in great geometrical masses of stone and concrete roaring with perfectly mechanized traffic—and smartly dressed men and women spending, spending with the money they had won by being far-sighted enough to foresee, way back in 1929, what was going to happen.[209]

As an additional manifestation of the (over)confidence of the times, 40 Wall Street reigned as the tallest building in the world in 1929, only to be outdone by the Chrysler Building in 1930, which itself was unseated from the throne by the Empire State Building eleven months later. Chapter 11 will develop this "tallest building" indicator a bit further. John Kenneth Galbraith succinctly and eloquently summarized the spirit (and literal construction activity!) of the times and the dynamic it imposed on prices: "Optimism built on optimism to drive prices up."[210]

A large part of consumer, business, and national confidence sprang from the ending of WWI and the redeployment of industrial efforts toward commercial, rather than military, ends. The Coolidge administration was particularly hands-off in its approach to handling markets, and prosperity was widespread.

Prohibition also played a role in the Florida land boom. Although unintended, the government's prohibition of the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages led money to flow to Florida, what William Johnson Frazer called "one of the countries leakiest spots on the country's dry border." The result was a surge in revenue that was deposited in Florida banks, which, due to banking regulation at the time (i.e., banks had been granted state charters and mandated to conduct business only within the state), effectively mandated that they lend this money out within Florida.

Every aspiring politician yearns for an opportunity to blame incumbents and the existing system for the ills faced by society, and the Great Crash and economic slowdown that followed provided such an opportunity. The early 1930s typify this spirit, and Roosevelt's 1932 campaign for the presidency touted the failure of market economics and Wall Street's self-seeking greed. In fact, his inaugural address captures this spirit:

Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.... In such a spirit on my part and on yours we face our common difficulties. They concern, thank God, only material things. Values have shrunken to fantastic levels; taxes have risen; our ability to pay has fallen; government of all kinds is faced by serious curtailment of income; the means of exchange are frozen in the currents of trade; the withered leaves of industrial enterprise lie on every side; farmers find no markets for their produce; the savings of many years in thousands of families are gone. More important, a host of unemployed citizens face the grim problem of existence, and an equally great number toil with little return. Only a foolish optimist can deny the dark realities of the moment.

Yet our distress comes from no failure of substance. We are stricken by no plague of locusts. Compared with the perils which our forefathers conquered because they believed and were not afraid, we have still much to be thankful for. Nature still offers her bounty and human efforts have multiplied it. Plenty is at our doorstep, but a generous use of it languishes in the very sight of the supply. Primarily this is because the rulers of the exchange of mankind's goods have failed, through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men.

True they have tried, but their efforts have been cast in the pattern of an outworn tradition. Faced by failure of credit they have proposed only the lending of more money. Stripped of the lure of profit by which to induce our people to follow their false leadership, they have resorted to exhortations, pleading tearfully for restored confidence. They know only the rules of a generation of self-seekers. They have no vision, and when there is no vision the people perish.

The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

Happiness lies not in the mere possession of money; it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort. The joy and moral stimulation of work no longer must be forgotten in the mad chase of evanescent profits. These dark days will be worth all they cost us if they teach us that our true destiny is not to be ministered unto but to minister to ourselves and to our fellow men.

Consider the biblical overtones invoked by using "money changers" rather than "speculators" and the overwhelming sense that someone must be blamed. Chancellor notes that "in place of market forces came federal welfare, housing and work programmes, bank deposit insurance, prices and incomes policies, minimum wage legislation, and a number of other measures. Speculation, whether in stocks, bonds, land, or commodities, was no longer to play such a key role in economic life."[211]

The sweeping set of government programs were organized around the three Rs of relief, recovery, and reform. The economic policies of the Roosevelt administration were based on getting Americans back to work and alleviating economic hardships (i.e., relief), helping the American economy to recover toward full potential, and providing a new regulatory framework, complete with appropriate government authorities, to oversee the economy and prevent a repeat of the Great Depression. The New Deal policies produced a plethora of new government programs and agencies, including major programs such as Social Security and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as well as the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Although such regulatory reform was designed to promote stability and prevent future hardships, it laid the roots of future troubles by creating issues of moral hazard through deposit insurance, a potentially unsustainable program of entitlements such as Social Security, labor market distortion via price floors (i.e., minimum wages), and the general growth of the government. The magnitude and impact of these programs by themselves suggest the 1920s and 1930s boom–bust sequence threatened the very fabric of the U.S. capitalist system. Though property rights were never directly threatened, the intention of Social Security and other programs was to redistribute from those who had, to those who needed.

One of the most important elements of a boom–bust sequence that helps one identify where in the cycle one might be is, to use language from epidemiology, the population of unaffected or unexposed individuals. When one hears that everyone, including those not traditionally active or invested in the market, is "in the market," then one might naturally (and accurately) assume that the boom cycle is far along and very mature (perhaps approaching expiration), with a limited population of infectable participants.

Consider Allen's description of the market in 1929:

Grocers, motormen, plumbers, seamstresses and speakeasy waiters were in the market. Even the rebellious intellectuals were there: loudly as they might lament the depressing effects of standardization and mass production upon American life, they found themselves quite ready to reap the fruits thereof.... The Big Bull Market had become a national mania.... The speculative fever was infecting the whole country. Stories of fortunes being made overnight were on everybody's lips.[212]

Table 7.4. The Five-Lens Approach to the Great Depression

Lens | Notes |

|---|---|

Microeconomics | Reflexive credit/collateral tendencies Higher prices induced buyers Lower prices induced sellers |

Macroeconomics | Inappropriately cheap money Financial innovation (leverage via "binders") |

Psychology | New era thinking (new industries) World's tallest skyscrapers (40 Wall, Chrysler, Empire State Building) |

Politics | End of war Prohibition inspired money flows Re-regulation, blame game |

Biology | Amateur Investors ("national mania") Silent Leadership (Florida governor, JP Morgan) |

Further, the development of financial products such as investment trusts to meet the desires of ordinary individuals to get involved in the market boomed: "During the first nine months of 1929, a new investment trust appeared for every working day and the industry issued over two and a half billion dollars worth of securities to the public."[213] These two elements—namely the broad involvement in the market and the tremendous boom in products designed to meet the needs of the previously uninvested—clearly tip the scales in favor of a very mature boom.

The epidemic lens also yields some insight into the aftermath of the Great Depression and subsequent speculative tendencies. The magnitude of the bust was such that a large percentage of the American population was negatively affected (some might say scarred) by the economic and financial implosion. Perhaps this "immunized" most citizens from the speculative fever that drives booms and busts? Might this be the reason that the United States did not have any major financial bubbles for decades after the Great Depression?

The logic of swarm leadership described in Chapter 5 is also helpful in understanding the 1920s and 1930s. For instance, the Florida land boom had lots of "informed" investors that drew the attention of the uninformed masses. John Martin, then governor of Florida, was quoted as having said "marvelous as is the wonder-story of Florida's recent achievements, these are but heralds of the dawn...." and S. Davies Warfield, president of the Seaboard Air Line Railway, supposedly talked of Miami's population exceeding 1 million within the next ten years.[214] Such informed members were able to lead the swarm of uniformed investors into the mid 1920s Florida land boom.

The list of similarly informed individuals that led the uninformed into the Great Crash is too long to mention, but the most famous quote is from Yale University professor Irving Fisher, who stated, "Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau" just weeks before the stock market crash in 1929.

This discussion of the Great Depression was intended to demonstrate the power of a multidisciplinary framework through which to analyze financial extremes. A summary of the discussion is listed in Table 7.4. The next chapter will similarly illustrate the power of this five-lens framework during the Japanese boom and bust.