The militaristic hubris that took Japan blindly into the Second World War found its counterpart in the speculative hubris of the Bubble Economy. History was repeating itself, except this time a stock market farce replaced the tragedy of war.

During the 1980s, Japan experienced an extraordinary speculative boom that resulted in a bust that has plagued the island nation for the last 20 years. This chapter describes the events that transpired during the 1980s and some of the resulting extremes witnessed in the course of unbridled speculation. The impact of the bust, which continues as this book is being written, is briefly considered as well, and the boom and bust are then evaluated via the five lenses presented in Part I.

Japanese society emphasizes harmony. The primary religions in Japan, Buddhism and Shintoism, are heavily oriented toward collectivism. The heavy influence of Confucian ideals also strengthens the primacy of group harmony over individual success. Further, theJapanese, not unlike many other homogenous groups, genuinely think of themselves as unique and different from other societies and cultures. The Japanese hold a deep belief that they are unlike other races, religions, or frankly, humans. This belief is not one restricted to behavior, for as noted in Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation, it actually begins with a notion that Japanese physiology is unique:

Japanese intestines were said to be different from those of Westerners and therefore unsuited to foreign beef and rice. It was even claimed that American skis were useless in Japan because the snow was different. At other times, pointing out such differences became a barely concealed expression of Japanese cultural nationalism and xenophobia: the Japanese brain was said to have a heightened sensitivity to the sounds of nature and a more intricate understanding of social relationships. The Japanese distrusted Western-style rationalism as being incompatible with the preservation of social harmony.... Japanese reason was described as "wet," like the cloying rice of the national diet (which formed the glue of the community), while Western reason was "dry" and individualistic. Even in the ethical sphere, the Japanese were said to be different. They did not feel guilt, only shame on public revelation of misdeeds. At the root of all these differences, both real and spurious, lay a profound distrust of individualism, which found its counterpart in a strong attachment to community and deference to authority.[215]

This deep cultural focus on community (relative to the Western focus on individuals) manifests itself throughout Japan's political-economic systems. Although the West has historically[216] focused on a limited role for government in business, markets, and industry, the Japanese believed in an active role for government in delivering administrative guidance to companies and industries. Likewise, although Westerners distrust monopolies, Japanese seek industrial champions. Finally, Western distinctions between business matters and individual relationships have no counterpart among the Japanese. In Japan, relationships and social harmony supersede virtually all else.

Many Japanese assert that their society is less selfish and more long-term-oriented than the West. Perhaps due to their feudal roots[217] and collectivist culture, hierarchy reigned supreme. Samurai values emphasized frugality, and savings rates were high. Administrative guidance helped channel these savings into the most appropriate investments. Market share was deemed a better objective than profits as it aligned the organization toward long-term success.

Given the limited individual role in virtually all matters economic, a long-term orientation, cultural values oriented around frugality and thrift, and a system designed around governmental guidance, Japan was a highly unlikely place for a speculative bubble to form. Yet a speculative bubble driven by individualistic short-term pursuit of profits is exactly what Japan experienced in the mid- to late 1980s. The collective shock to Japan of the bubble and its subsequent bursting was monumental and continues to be felt today.

Japan had been absolutely devastated by the Second World War. In the aftermath, during which the United States and other nations provided meaningful economic support, Japan implemented numerous policies to promote savings. These savings, it can be argued, ultimately enabled banks to feel more "flush" and therefore effectively encouraged the expansion of credit—credit that fueled much of Japan's economic growth after the war.

The massive economic transformation that transpired between 1953 and 1973 generated tremendous confidence in the country. According to Paul Krugman, "in the space of two decades a largely agricultural nation became the world's largest exporter of steels and automobiles, greater Tokyo became the world's largest and arguably most vibrant metropolitan area, and the standard of living made a quantum leap."[218] As a further illustration (albeit less direct) of the resignation that "Japan had won," Krugman went on to author The Age of Diminished Expectations in which he effectively stated the United States was potentially losing the economic race to government/private partnerships like Japan.

During the 1980s, Japan's economy grew by leaps and bounds. The period was characterized by fast growth, low unemployment, and big profits. Although these conditions were highly supportive of rising asset prices, the property market raced ahead at unsustainable rates. The property bubble reached truly extraordinary heights, particularly when compared with America, and ultimately served as the foundation of the entire "Bubble Economy," as it has since been known. Consider the following facts, as summarized by journalist-turned-strategist Christopher Wood:[219]

America is twenty-five times bigger than Japan in terms of its physical area. Yet Japan's property market at the end of 1989 was still reckoned by sober people in the government's Management and Coordination Agency to be worth over ¥2,000 trillion, or four times the estimated ¥500 trillion value of American property. This is truly history's greatest accumulation of wealth in one country. It creates ludicrous anomalies. In early 1990 Japan in theory was able to buy the whole of America by selling off metropolitan Tokyo, or all of Canada by hawking the grounds of the Imperial Palace.[220]

Crazy as the absolute land valuations might seem, the actively traded market that developed for golf course memberships is perhaps more noteworthy as another extreme of the land bubble. Wood's commentary captures the spirit of the times better than any other:

Not surprisingly, given the national obsession with golf, this became a ludicrously overheated market in the late 1980s. An estimated 1.8 million people own golf club memberships in Japan; the prices of these memberships, which are traded like securities, range from a few million yen up to the ¥250 million range. At the peak, Japan's 1,700 golf courses were estimated to have a total membership market value of some $200 billion.[221]

There are three primary reasons that land values in Japan were so high: physical scarcity, feudal tradition, and government policies. The following discussion will examine these three causal factors of the property bubble in greater detail, but for now, it is important to note that they created a market that was not particularly liquid.

Very few transactions (compared to what one might expect from such a highly valued market) actually took place. Although this might mean such high property values were meaningless, the fact that they served as collateral for a significant portion of bank lending meant that prices, regardless of their true "accuracy," were very meaningful. In addition to supporting loans, much of the credit created through and supported by Japanese property price gains ultimately found its way into various assets and foreign property investments.

Trophy properties in the United States soon dominated the attention of the Japanese. New York's Rockefeller Center and the Exxon Building were two prized properties for which the Japanese paid handsomely. Japan's Mitsui Real Estate Company paid $625 million for the Exxon building on Sixth Avenue, well above Exxon's $310 million asking price, solely to be listed in the Guinness Book of World Records.[222] In 1990, a medium-sized Japanese company purchased America's most famous golf course, Pebble Beach, for $831 million. Hawaii also became a target for Japanese investor interest. Between 1985 and early 1991, Japanese investors purchased or financed the building of all but two of the main hotel resorts in Hawaii.[223] The Grand Hyatt Wailea Resort and Spa on Maui (which opened its doors in 1991) was built for a total cost of over $600 million, which equated to a per room investment of over $760,000. According to Anthony Downs, former chairman of the Real Estate Research Corporation and a current Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, the hotel needed to charge over $700 per room per night (in the 1990s) and maintain occupancy of at least 75 percent in order to just break even.

As the Japanese infatuation with property was bubbling to ever-higher heights, their interest in art gained tremendous momentum. Edward Chancellor's description summarizes the phenomenon extraordinarily well: "In the 1980s, the combination of ambitious Western auctioneers, promoting art with every trick in the book, and Japanese speculators, their wallets swollen with bubble profits, created the most extravagant art market on record."[224] Peter Watson, in his book From Manet to Manhattan: The Rise of the Modern Art Market, described the 1988–1990 period, driven primarily by Japanese buyers, as "the most sensational that the art world has ever seen."

The New York Times reported on the results of a Christie's art auction that took place in late March 1987 in London.[225] In the highest price ever paid for a painting, van Gogh's Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers had been sold to an unidentified foreign buyer for $39.9 million, well above the previous auction record for a painting of $10.4 million for Andrea Mantegna's Adoration of the Magi. The foreign buyer was later identified as Yasuo Goto of Yasuda Fire & Marine, a Japanese insurance company.

On November 30, 1989, Tomonori Tsurumaki, a Japanese real estate developer, won an auction for Picasso's Pierrette's Wedding (Les Noces de Pierrette) that took place at the Paris auction house Drouot. Tsurumaki was bidding from the New Otani hotel in Tokyo while he was hosting a party launching his newest real estate development project—a $500 million auto racing resort to be called "Nippon Autopolis." After winning the Picasso, Tsurumaki noted that "One highlight of Autopolis will be a museum featuring works by such famous artists as Monet, Renoir, Chagall, and Magritte—and now, of course, this world famous Picasso."[226] The height of the Japanese art craze was reached when Ryoei Saito, chairman of Daishowa Paper Manufacturing, paid $82.5 million for van Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Gachet and over $78 million for Renoir's Le Moulin de la Galette in May 1990. He then proceeded to shock the art world by stating he would cremate the paintings along with his body upon his death.[227]

Not surprisingly, Japanese investors found a receptive and fertile opportunity to speculate in the stock market. In attempting to summarize the magnitude of the stock market bubble, Krugman noted that "at the beginning of 1990, the market capitalization of Japan—the total value of all the stocks of all the nation's companies—was larger than that of the United States, which had twice Japan's population and more than twice its gross domestic product."

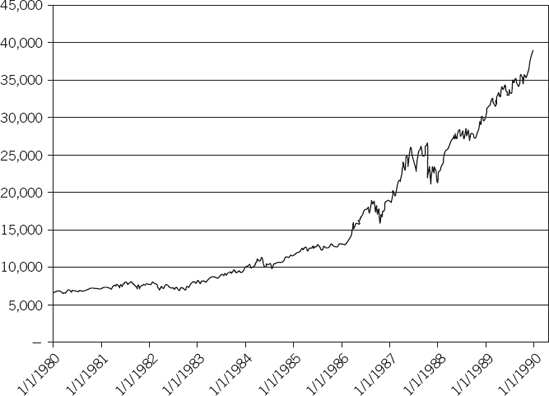

Before describing the phenomenon in greater depth, a quick glance at Figure 8.1 demonstrates the tremendous boom the Japanese stock market experienced during the 1980s.

As is clear from the increasingly vertical move in share prices in the late 1980s in Japan, speculative juices were flowing rapidly. One stock that captures the spirit of the times perhaps better than any other is Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT), the national telephone company. After being privatized in 1985 to encourage competition, NTT shares were floated to the public in several tranches. By November 1987, when the company did a further listing of shares valued at over $38 billion, the company had a total market valuation of approximately $300 billion. To provide some context for this figure, the New York Times suggested at the time that NTT was worth more than the stock markets of Switzerland and France combined.[228] Incidentally, Chancellor noted that NTT was worth more than the entire value of the West German and Hong Kong stock markets, combined. Suffice it to say, NTT was a very highly valued company!

On top of this already ebullient market, the fact that most Japanese companies owned land provided justification for highly priced shares as professional and amateur analysts alike highlighted the "hidden" real estate values that were not fully reflected in official financial statements. Such land and property valuation was commonplace. Chancellor notes "even NTT was valued primarily for its land assets rather than as a telecommunications company. Propelled by its extensive landholdings, the market value of Tokyo Electric Power increased by a greater value than that of all the stocks listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange."[229] Even airlines were considered land plays, with All Nippon Airways rising to 1,200 times earnings and Japan Airlines at 400 times (it was thought to have less land).

To eliminate the noise originating from individual extremes, let us take a look at some of the valuations placed by the market on various sectors. Table 8.1 highlights the heights to which several sectors rose.

In aggregate, the asset price boom that took place in Japan during the late 1980s was perhaps the world's most spectacular (and ephemeral) wealth creation event (up to that date).[230] As asset markets sprinted to unsustainable levels, Japanese authorities grew increasingly concerned and attempted to dampen speculative behavior. The Bank of Japan's incoming governor feared high housing prices might erode social harmony. (Separately, it is interesting to note that such social harmony was so highly valued by society that banks began designing products to allow such harmony to coexist with lofty valuations. One such product, according to Kindelberger and Aliber, was a hundred-year, three-generation mortgage!) In 1989, the Bank of Japan issued new regulations limiting the growth of real estate loans to the growth rate of total loans and began raising rates. The Bank of Japan raised the interest rate from 2.5 percent in May 1989 to 6.0 percent in August 1990 over the course of five incremental policy actions—undoing the reduction of interest rates from 5 percent in January 1986 to 2.5 percent by February 1987.[231]

Figure 8.2 below, taken from Richard Koo's The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics: Lessons from Japan's Great Recession, visually demonstrates the magnitude of the correction in the stock market, land market, and even the golf course market.

Given the magnitude of the wealth created and the unsustainable heights to which asset prices had risen, the bursting of the bubble economy was inevitably going to have a massive financial and economic impact on corporations, investors, consumers, and perhaps most importantly, the banks that had fueled the surge and accepted inflated assets as collateral. Kindelberger and Aliber eloquently summarize the bust:

Figure 8.2. Bursting of the Bubble Economy Source: Richard Koo, The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2009). Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Once the rate of growth of bank loans slowed, some recent buyers of real estate developed a cash bind; their rental income was still smaller than the interest payments on their mortgages, but they could no longer obtain the cash needed... from new loans. Some of these investors then became distress sellers. The combination of the sharp reduction in the rate of growth of credit for real estate and these distress sales caused real estate prices to decline; the cliché that the price of land always rises was tested and found to be false.

Stock prices and real estate prices began to decline at the beginning of 1990; stock prices declined by 30% in 1990 and an additional 30% in 1991. The stock price trend in Japan was downward... and at the beginning of 2003, stock prices in Japan were at the same level they had been 20 years earlier, even though the real economy was much larger....

Now the perpetual motion machine began to work in reverse. Property sales led to declines in property prices. The decline in real estate prices and stock prices meant that bank capital was declining; banks were now much more constrained in making loans....

Bankruptcies increased, and the banks and other financial institutions incurred large loan losses. Those nonbank financial institutions that specialized in making real estate loans were in great distress.[232]

The Japanese boom and bust sequence exhibited many unique elements and took place in the most unlikely of locations—an administratively guided economy in which thrift and long-term thinking combined with market share prioritization over profits and the desire for social harmony at the expense of individual success. The application of the five lenses in this context will build the framework's relevance across the cultural spectrum and will help with the formulation of a generic framework through which to think about booms and busts.

At the very root of the bubble economy was a tremendous boom and bust sequence in the property market. Land was, simply put, the foundation upon which the entire rickety system was built. By lowering rates to 2.5 percent in 1986, the Bank of Japan threw fuel on the already-burning speculative fire. Consider the reflexive dynamic eloquently described by Wood:

This sparked a liquidity boom to beat all others. At its center lay the economy's main engine of credit creation, the banks. They were able to use a rising stock market to literally create bank capital and thus boost their lending. That extra credit was funneled back into two main markets (shares and property), boosting the value of banks' favored collateral (shares and property) against which to lend still more money.[233]

Further, the utter dominance of property as a source of collateral (some estimates indicate that real estate may have served as the backing for around 80 percent of all loans outstanding in Japan[234]) virtually assured that any dynamic that transpired (boom in the case of rising prices or bust in the case of falling prices) was surely going to tend away from any equilibrium condition that might theoretically exist.

Nevertheless, one might argue that the origin of the boom was a sound economic success story in which corporate Japan began growing profits as they took market share from global competitors. Over time, however, this initial fundamental development transformed into a reflexive, self-fulfilling and self-sustaining asset boom that ultimately exceeded its own capabilities and imploded upon itself.

Because of a savings-oriented culture and the Bank of Japan's decision to lower the official discount rate from 5 percent to 2.5 percent between January 1986 and February 1987, banks were flush with cash and money was close to free. As noted in the previous section, this reduction of rates ignited a liquidity boom that fed upon itself in an unrivaled manner.

Another factor that proved to be quite important was the deregulation and liberalization of the financial sector that enabled Japanese banks to increase the amount of loans guaranteed by property. Although this was initially a result of international lobbying to enable foreign banks to compete for Japanese business, the largest beneficiaries of the liberalization process were probably the Japanese banks.

A third factor was the Japanese yen. Because of external influences on the Japanese government to moderate the rate of Japanese currency appreciation, the Bank of Japan was active in the foreign exchange markets by constantly selling yen. Although the direct result of these efforts was a slower appreciation in the yen, the indirect result of it was a flooding of the system with yen. According to Kindelberger and Aliber:

The result of extensive intervention was that money supply in Japan began to increase at an exceptional rate—that is, the monetary base was increasing. The increase in reserves of the Japanese banks meant that they were able to increase their loans at a rapid rate.[235]

Was the Japanese government's desire to control the currency the ultimate reason for many of these boom–bust oriented policies? Though it is not clear, it does seem stopping and/or slowing a rising yen, and the pressure that it puts on export industries in the country, was the target of policy efforts. Might the government have sought to induce speculation in a quest to get asset markets to support real economic activity?

The following quote, attributed to an unnamed executive at the Bank of Japan, suggests that asset price inflation may in fact have been the Bank of Japan's goal:

We intended first to boost the stock and property markets. Supported by this safety net—rising markets—export-oriented industries were supposed to reshape themselves so they could adapt to a domestic-led economy. This step was then supposed to bring about an enormous growth of assets over every economic sector. This wealth effect would in turn touch off personal consumption and residential investment, followed by an increase of investment in plant and equipment. In the end, loosened monetary policy would boost real economic growth.[236]

In discussing the observation made by Charles Mackay in Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds that "men think in herds, go mad in herds, but only recover their senses one by one,"[237] Wood notes that "as a group culture that discourages individualistic thinking, the Japanese are even more vulnerable than most to this decidedly human trait."[238] The cultural values that dominated pre-1980s Japan were uniquely communal in that social harmony was valued more highly than individual happiness. In a society focused on conformity and not being different, the mere introduction of the slightest differences can be quite destabilizing.

An analogy with preschool appears apt here. My daughter goes to a Montessori school in Boston. Virtually all the kids in her class (they're mostly 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds) simply go with the flow. With the exception of the random tantrum that inevitably arises among children of this age, the group is quite harmonious. However, there are some key moments during the day when an individual opinion snowballs rapidly into group thinking. Arriving one afternoon shortly before snack time to pick up my daughter, I patiently (and covertly) observed the classroom dynamic. The teacher was about to put out some fruit and crackers when one young boy yelled, "I don't like crackers." In an almost comical sequence of events that left the teacher confused, probably frustrated, and definitely busy, all the other kids started agreeing. Nobody wanted crackers, despite the fact that I have seen virtually all of the kids voraciously eating crackers on other afternoons. It was as if a domino had fallen, knocking over all other opinions.

Not unlike this pre-primary classroom, Japan—a consensus-oriented, thrifty society focused on long-term economic development—found itself rapidly pursuing conspicuous consumption (in the form of art and trophy properties) and short-term individual gain despite harmful long-term implications.

Just as this harmonious society found itself drifting rapidly toward overconfidence and economic hubris during the boom phase of the cycle, so too did the bust phase of the cycle lead to a consensus of dejection, underconfidence, and utter despair. In referencing the dishonor that spread among Japan's financial services employees during the 1990s and onward, Wood notes that "this demoralization matters because it can become self-feeding. In a consensus society where there are few contrarians, yesterday's collective euphoria can too easily degenerate into tomorrow's collective panic."[239]

As this collectivist, consensus-oriented approach to life combined with the extraordinary confidence that emerged as a result of Japan's postwar economic success, textbook versions of cognitive biases soon emerged and were clearly recognizable. Might a society that had experienced great economic success (such success that books such as Japan as Number One were published) develop a collective sense of overconfidence? Would the availability bias lead to the extrapolation of most recent trends (land prices have been rising for a long time) into future projections (land prices will continue rising for a long time)? Might the public stories of grandiose global accomplishment such as the purchase of Rockefeller Center or prized Picasso paintings be seen as representative of Japanese society's new global economic status more than as examples of conspicuous consumption? In thinking about contractions, might anchoring and insufficient adjustment lead to the belief that a multiyear asset price deflation was particularly unlikely?

Although the number of political and regulatory factors that influenced the boom and subsequent bust are too numerous to fully describe here, there are several policies that seem vital to understanding the bubble economy. Given the root cause of the bubble economy was an unsustainable, credit-fueled rise in property prices, this section will focus on two main types of political and regulatory considerations that directly affected property prices: tax policies and financial de-regulation and credit controls.

In terms of tax policies, two taxes likely influenced the incentives to own property. The first tax, which might be deemed penal property taxation, was designed to discourage short-term trading of properties. The policy was straightforward, albeit very distortionary: "If land is sold within two years of its purchase, then 150 percent of the capital gain is added to the seller's annual income and taxed accordingly. If sold within five years, then 100 percent of the gain is added to income and taxed."[240] What effect might this have on purchasers who owned real estate that appreciated rapidly in the first five years of ownership? What might such taxes do to the trading volume and liquidity of these assets? By distorting the supply of housing that was available for purchase each year, these policies created a false sense of scarcity, resulting rapidly rising prices. Further, this impact might also have created "house money" effects in which owners were not as disturbed or concerned about initial housing losses.

Another Japanese tax that seemed to affect real estate prices by artificially increasing the demand for property was the inheritance tax. The tax had a marginal rate structure in which mortgages were fully deductible from assessed property values, and property assessments (for tax purposes) were often well below market values (as is the case in much of America). Thus, it was possible to create negative asset value by purchasing a property with significant leverage. This negative value could offset other positive asset values and thereby reduce the tax burden. Citing this as a "well-known bequest strategy," Takatoshi Ito described the process as follows: "Those who were planning a bequest to their heirs were alarmed as their real estate values went up. In order to avoid high taxes, they purchased more real estate with high leverage, so that they could lessen the bequest tax burden. The higher prices generated more demand....[which may] have created an upward spiral in prices."[241]

Financial deregulation might also have contributed to the upward property price spiral, and its subsequent reversal. Initially due to pressure to open up the banking sector to foreign competition (the Americans wanted the ability to compete for business in Tokyo on comparable terms to the Japanese ability to compete for business in New York), Japanese financial deregulation was ultimately about decreasing administrative guidance.

As noted by Kindelberger and Aliber, "interest rate ceilings on deposits and loans were raised. Window guidance became much less extensive. The restrictions on the foreign investments of Japanese firms were relaxed."[242] The overarching philosophy is best summarized as follows: "Traditional banks were safe, but also very conservative; arguably, they failed to direct capital to its most productive uses. The cure, argued reformers, was both more freedom and more competition: let banks lend where they thought best, andallow more players to compete for public savings."[243] As a result of this deregulation wave, banks began increasing the amount of money they lent against property.

Eventually, the rapid rise in asset prices caught the attention of policy makers. In an effort to deflate the bubble, the government began reversing some of these pro-compeititon policies. Credit policies were reconsidered, with the idea that slowing access to property financing might defuse the rising inequality resulting from skyrocketing prices. The government implemented credit controls in April 1990 stipulating that any increase in bank lending for property must be smaller than the increase in a bank's overall loan book. Given the high percentage of lending that had been collateralized using property prior to this mandate, credit effectively stopped flowing toward property. Deregulation of the bond market also ensured that this mandate had teeth as corporate nonproperty borrowing (a very traditional role for Japanese banks) was slowly shifting away from banks to the bond market, a trend that accelerated concomitantly with financial deregulation.[244] The market rapidly swung from "an illiquid market where no one wants to sell (the traditional condition of this land-worshipping society) to an equally illiquid market where no one wants to buy."[245]

The two lenses of Chapter 5 are quite powerful in evaluating theJapanese bubble economy. The epidemic model provides a view of the bubble economy's maturity and the relative proximity of a bust. The Far Eastern Economic Review noted in 1988 that "stocks have become a national street-level preoccupation" and near the top of the best-seller list was a Japanese comic book about the economy and the stock market.[246] By the late 1980s, more than 22 million people were investing in the stock market, up from around 13–14 million in the mid 1980s. Nomura Securities, the largest of the domestic brokerage firms, had more than 5 million customers, mainly Japanese housewives, who regularly invested with Nomura salesmen. Speculation was encouraged, and through broker "guidance," more than a third of stocks held in private accounts were held in margin accounts.[247]

Given the high proportion of the infectable population that appeared infected, an imminent slowdown of infections seemed likely. In fact, the rapid acceleration in the number of brokerage accounts opened by individual investors was a spectacular early warning indicator of the beginning of the end of the bubble economy.

Any consensus-oriented collection of individuals is highly prone—like the bees in a swarm—to the silent leadership of a seemingly informed individual. Consider the earlier preschool example, in which the establishment of the "we don't like crackers" conclusion in the classroom is not dissimilar to the movement of ants described in Chapter 5. The investment climate in Japan through the middle of the 1980s was a stable equilibrium with everyone "tied," in an opinion sense, to everyone else. Social harmony, conformity, and consensus ruled the day. For whatever reason, once the balance tipped[248] toward the pursuit of immediate individual gain, the whole swarm of formerly long-term-oriented social beings became speculators. The cohesive power of communal thinking that had stabilized Japanese society for so long was now creating a speculative frenzy. The result was a spectacular manifestation of herd behavior in speculation, despite the view that gambling was a Chinese vice from which the Japanese were immune:

The Japanese were particularly susceptible to the lure of the stock market....[because] they have a tendency to exhibit herdlike behavior when pursuing a certain activity, whether at work or play. This was said to stem from the communal demands of rice farming, which had fostered a national shudankizoku ishiki (group consciousness). During the war, Japan was portrayed in government propaganda as "one hundred million hearts beating as one." After the October crash, the president of a securities house boasted that Japan had survived the period of volatility because it was "a consensus society—a nation that likes to move in one direction."[249]

Table 8.2. The Five-Lens Approach to the Japanese Boom and Bust

Lens | Notes |

|---|---|

Microeconomics | Reflexive credit/collateral dynamic Higher prices induced buyers Lower prices induced sellers |

Macroeconomics | Inappropriately cheap money Financial innovation (100 year mortgages) |

Psychology | New era thinking (economic power) Conformity-driven social harmony Conspicuous consumption (trophy art) Economic overconfidence |

Politics | Supply/demand distortions (penal property taxation) De-regulation of the banking industry Credit regulations that distorted incentives |

Biology | Amateur investors (housewives) Silent Leadership (communal philosophies) Popular Media (Japan as Number One) |

Being a consensus society is definitely a two-edged sword, for if consensus were organized around a stable equilibrium, all would be well. However, if the accepted perspective was one of disequilibrium, short-termism, or speculative behavior, then instability would dominate and the former stability would evaporate.

As the discussion above has demonstrated, the five lenses presented in Part I were able to shed light on the bubble economy of Japan in the late 1980s and the subsequent bust during the 1990s in a manner not possible with the use of only one lens. Table 8.2 summarizes the five lens approach to thinking about the "Bubble Economy." The next chapter utilizes the fives lenses to evaluate the Asian financial crisis that emerged in the mid 1990s and the contagion effects it had on the rest of the world.