The great Asian slump is one for the record books. Never in the course of economic events—not even in the early years of the Depression—has so large a part of the world economy experienced so devastating a fall from grace.

In many ways the seeds of economic success in Asia were sown in the early aftermath of World War II. In an effort to rebuild societies and generate long-term economic growth, many Asian countries adopted export-oriented development policies designed to utilize their abundant (and therefore cheap) labor to meet global demands. Combined with increased opportunities for trade, the economic strategies caught a massive tailwind in the early 1990s and asset markets took notice, rising to lofty heights. The resulting bubble eventually collapsed in 1997 and 1998, with the ripple effects being felt around the world.

The early to mid-1990s were a spectacular time for many East Asian economies (Japan, as we have just learned, was an exception). A 1993 book titled the East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy, began with this summary:

East Asia has a record of high and sustained economic growth. From 1965 to 1990 the twenty-three economies of East Asia grew faster than all other regions of the world. Most of this achievement is attributable to seemingly miraculous growth in just eight economies: Japan; the "four Tigers"—Hong Kong, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, China; and the three newly industrializing economies of Southeast Asia—Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand.[250]

Against this backdrop of economic performance, it is not surprising that booms might develop across the region's asset markets. According to Robert Barbara, "the booms were initially sensible, reflecting sound investment opportunities. The dynamics were straightforward. The collapse of the former Soviet Union and China's newfound willingness to interact with capitalist nations supercharged trade and capital flows between the developed world and emerging Asian economies."[251]

Rapid growth was taking place throughout the entire region, albeit with slightly nuanced and different driving factors in each country. South Korea, which had been devastated by the war, embarked on a remarkable period of economic growth that utilized high savings rates, cheap labor, an inexpensive currency, and strong industrial policy to produce products needed by global consumers and corporations. Singapore, which was literally a swamp in the 1950s, embarked on a strategy to become a corruption free, rule-of-law oriented outpost in a land of crony capitalists and in so doing, elevated itself to first-world status. Deng Xiaoping's rise to power in China resulted in an economic revival that opened the country up to international trade and global investment, as well as an economic reform agenda more typically found in capitalist nations. For many years following this policy shift, China grew its GDP in excess of 10 percent per year. Hong Kong transformed into a regional, if not global, financial center. Manufacturing activity surged in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia as globalization took hold, trade barriers were lowered, and protectionism retreated.

Many stock markets in the region rose at rapid rates. In 1993, for instance, many East Asian countries saw their stock markets double in value, with growth continuing into 1994. Figure 9.1 graphs the performance of the Philippine, Thai, Malaysian, and Indonesian markets in 1993. Real estate prices rose throughout the region as the optimistic outlook combined with inexpensive capital to create significant demand. In sum, Asian economies and asset markets boomed.

In essence, what occurred was simple: Abundant capital combined with cheap labor to produce competitive economies. The developed world (or more precisely, the rich world) got excited about these prospects and began pouring money (primarily dollars) into the East Asian markets. As a result, many Asian currencies appreciated quite rapidly and banks and local corporations borrowed significant sums of U.S. dollars (i.e., not local currency). Kindelberger and Aliber note the importance of the interconnections that began to form between East Asian countries and the developed world:

China, Thailand, and the other East Asian countries were on the receiving end of outsourcing by American, Japanese, and European firms that wanted cheaper sources of supply for established domestic markets. Rapid economic growth was both the result and cause of the inflow of foreign capital, especially from Japan. Japanese investment initially took the form of construction of manufacturing plants to take advantage of lower labor costs...from there a large part of the production would be exported, some to the United States, some to Japan, and some to third countries.... The buzzword was export-led growth, which was almost always based on a low value for the countries' currency in the foreign exchange market.[252]

The system fed upon itself, and soon Americans were outsourcing jobs to Korea, and in turn the Koreas were outsourcing jobs to China and Indonesia, where labor was even cheaper. In many ways, the whole chain was based on two primary enabling factors in the production country: inexpensive labor, and cheap currencies. As part of this "game," countries sought to constantly keep their currencies undervalued. In fact, on January 1, 1994, the Chinese government effectively devalued their currency relative to the U.S. dollar by ~50 percent. Might this action have provided a tremendous boost to Chinese exporters (at the expense of other Southeast Asian exporters)? In fact, it's possible that the 1994 Chinese devaluation may have in fact been one of the primary catalysts for the Asian financial crisis.

"Ground zero" in this Asian export-oriented game was Thailand. It typified everything about the boom and also served as the catalyst for the regional bust. Let us now turn to Thailand to understand what occurred within it and how it illustrates the boom dynamics of the region.

On the surface, it seems odd that a country like Thailand could be responsible for a global economic meltdown that resulted in debt defaults in Russia, the collapse of perhaps the world's largest hedge fund, and economic and currency contractions to rival the largest in history. In The Return of Depression Economics, Paul Krugman explains:

The world economy is almost inconceivably huge, and in the commercial scheme of things, Thailand is pretty marginal. Despite rapid growth in the 1980s and 1990s, it is still a poor country; all those people have a combined purchasing power no greater than that of the population of Massachusetts. One might have thought that Thai economic affairs, unlike those of an economic behemoth like Japan, were of interest only to the Thais, their immediate neighbors, and those businesses with a direct financial stake in the country. But the 1997 devaluation of Thailand's currency, the baht, triggered a financial avalanche that buried much of Asia.[253]

It was the devaluation of the Thai baht that eventually snowballed into a global mess, but before the bust, there had been a great boom. From 1985 to 1996, Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda enacted policies that opened the doors of the economy to the outside world. During this time, Thailand was one of the world's fastest growing economies and averaged annual GDP growth of 9.4 percent. Cheap labor, fiscal conservatism, and natural resources formed a powerful cocktail that modernized the formerly agricultural-dominated economy into a manufacturing-led, export-oriented powerhouse.

Foreign capital came to Thailand in droves in the early 1990s, and with its arrival, the country's financial self-sufficiency began to rapidly erode. Although it had basically self-funded its growth from domestic savings through the early 1990s[254], Thailand grew increasingly dependent on foreign capital, most of which was being lent in U.S. dollars.[255]

Several factors contributed to the rapid inflow of capital into Thailand during the early to mid-1990s, including several external factors. To begin, the resolution of the Latin American debt crises and the fall of the Soviet Union made investing in riskier places in the world more fashionable. Second, the sharp drop of interest rates in the developed world drove investors on a global search for better yields. Third, development agencies like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank began rapidly increasing their funding into emerging Asian countries like Thailand. And finally, there was the rapid growth of emerging markets funds (due in no small part to the name change—see "Third World Becomes Emerging Markets") that began allocating capital in a diversified manner to developing countries like Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the like.

As foreign inflows began coming into Thailand in greater and greater volumes, the stock market rose simultaneously. Might this have been a sign that capital was being recycled into speculative investing in shares? Krugman describes the phenomenon as follows:

As more and more loans poured in from abroad, then, the result was a massive expansion of credit, which fueled a wave of new investment. Some of this took the form of actual construction, mainly office and apartment buildings, but there was a lot of pure speculation too, mainly in real estate, but also in stocks.[256]

As the credit-fueled boom continued, non-bank finance companies sprung up everywhere. These institutions were usually controlled by a relative of a government official and were believed to have implicit government guarantees—enabling them to raise money at advantageous rates from respected banks and foreign lenders. These finance companies could then re-lend the capital to riskier projects or speculative ventures at higher rates to capture the spread. The implication of these relationships is that the government would backstop any losses, but that gains would accrue only to the finance company. Such "crony capitalism," as this system was later named, was widespread in Asia. Some have argued that this crony capitalism was in fact a very rational way of doing business as it enabled transactions in the absence of strong contract law.[257]

In the winter of 1996, against this backdrop of inefficient capital allocation via relationship lending practices, a dramatic concern emerged that began to spook foreign investors. Consumer finance companies began reporting large losses. Might this have been a manifestation of the 1994 Chinese devaluation that decreased the competitiveness of Thai exports (relative to Chinese exports)? Many of these companies had been set up by large domestic banks to circumvent regulations that prevented them from growing their consumer lending practices as rapidly as they would like. Foreign inflows began to slow, and eventually reversed.[258] Although capital inflows into the emerging Asian countries had been approximately $93 billion in 1996, by 1997 that number had turned into an outflow of approximately $12 billion.[259]

Eventually, the outflow of currency created downward pressure on the currency, something the government sought to prevent. On July 2, 1997, after expending significant reserves in an attempt to defend the currency, the Thai baht was allowed to depreciate and moved from a price of 25 baht per U.S. dollar to more than 55 baht per dollar in early 1998. Such a currency move could have a devastating effect on those with misalignment between their earning currency and their borrowing currency; to illustrate the point, consider the following hypothetical example.

Mr. T is a Thai businessman who decides to borrow $10,000,000 to expand his business. He doesn't need dollars, but because the rate to borrow them is cheaper and the bank is willing to lend to him at a good rate, he takes the $10 million loan and converts it to Thai baht. At the time, 25 baht = 1 US$, so he gets 250 million baht for his loan. He is not concerned about the loan because his business is healthy (but his earnings are all in baht). His business continues to grow, and Mr. T uses the cash flow to reinvest in the business rather than to repay the loan. Then disaster strikes. For simplicity of math, let's say that the baht is now worth 50 baht = 1 US$. Now, in order to repay the $10 million loan, Mr. T must come up with 500 million baht. The loan value doubled in local currency terms, effectively bankrupting Mr. T.

This is exactly what happened to thousands of individual entrepreneurs, banks, and big businesses in Thailand during the Asian financial crisis. Because foreign capital sources feared that they might not get paid back, they all retrenched and began recalling capital whenever possible, thereby creating an effective bank run on Thailand. Everyone wanted their money back at the same time, creating a self-fulfilling vicious cycle of selling assets at depressed values to repay loans, but also further depressing values in the process. The largest Thai finance company, Finance One, which was worth over $5.5 billion at one point, collapsed completely.[260]

To complicate the situation, in order to prevent the currency from continuing to fall, Thai authorities began to sharply raise interest rates to attract capital. Although the strategy worked to stabilize the currency (the baht was trading at ~36 baht = 1 U.S. dollar by the end of 1998), it increased the cost of doing business and slowed the economy so dramatically it entered a recession, with GDP shrinking by approximately 2.2 percent in 1998. Needless to say, confidence in the Thai economy was shattered. This loss of confidence led to less economic activity, which fulfilled fears of a slowing economy, which hurt companies, banks, and consumers, which led to lower confidence. The feedback loop was nasty.

But the question remains: How and why did the problems in Thailand create a financial tsunami that engulfed so many other, seemingly unrelated countries and organizations? Although Thailand's trading partners would be hurt because of the economic slowdown in Thailand, an important new mechanism through which Thailand's contagious disease spread were the same emerging markets funds that had enabled its boom. When bad news and financial losses came in from Thailand, fund managers needed to reduce holdings throughout the region to meet redemption requests from investors. Regardless of how countries may have differed, they were linked in the portfolios of these fund managers and hence were all vulnerable to self-validating panics.

To illustrate this concept in action, consider the following simplified scenario. A fund manager has chosen to invest in five countries and has spread his money equally between them (20 percent of the portfolio to each). Now, because of economic hardships in Country A, the stock market of Country A has fallen 50 percent. Now, instead of having 20 percent in each of five countries, our fund manager has 11.1 percent in Country A and 22.2 percent of his portfolio in each of the other countries. Assuming he wants to return to his prior country weightings, he must now sell shares of companies in Country B, Country C, Country D, and Country E—despite the fact that these countries have not had the same economic difficulties as Country A. This contagion effect is further complicated by the risk that our fund manager faces investor redemptions, in which case he might indiscriminately be selling all countries. Thus, even though the spark started in Country A, the flames might eventually engulf all five countries.

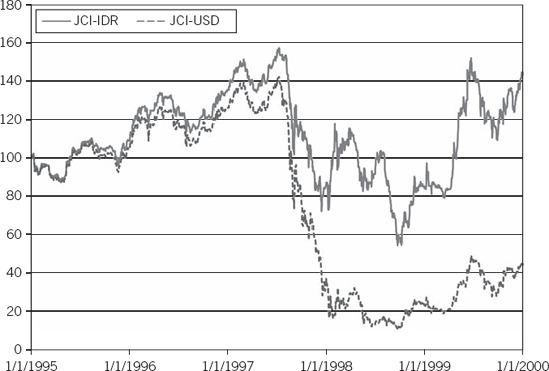

Through such capital market linkages, the panic spread from Thailand and eventually engulfed most of Asia, Russia, most other emerging markets, and the famed U.S. hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. To appreciate the magnitude of the capital markets impact, particularly when combined with currency impacts, consider Figure 9.2, which illustrates the performance of the Jakarta Stock Exchange Composite Index from January 1, 1995 through December 31, 1999 in U.S. dollar and Indonesian rupiah terms. Note that the U.S. dollar–denominated chart reflects what most emerging markets managers experienced. Peak to trough declines during this period were 65 percent in local currency terms and 93 percent in U.S. dollar terms. Over the 5-year period displayed in the chart, the index actually rose 44 percent in Indonesian rupiah terms (granted, the currency fell a great deal) but fell more than 55 percent in U.S. dollar terms.

Given the complexity of the East Asian financial crisis in terms of number of countries, governments, nongovernmental organizations, and currencies involved, it is impossible in several pages to utilize the five lenses of Part I in a comprehensive manner. Instead, this section will highlight a handful of illustrative issues.

As the rapid transmission of bank losses into a reversal of foreign fund flows and a self-validating panic demonstrated, the events in Asia during 1997 and 1998 were highly reflexive. They were not self-correcting in the traditional sense of efficiency. The primary cause of this reflexivity was the use of borrowed money that was collateralized by assets—assets which had their values inflated by the excess purchasing power generated through borrowed money. Because these are not self-correcting dynamics, they become quite disruptive and tend toward disequilibria.

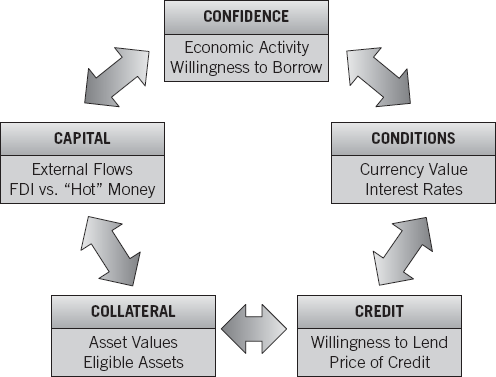

The dynamics leading to disequilibrium can be summarized as a self-reinforcing, self-validating reflexive feedback loop that connects what I label the five Cs—confidence, collateral, credit, conditions, and capital, as shown in Figure 9.3. During the boom phase of the cycle, confidence inspires credit, credit improves collateral values, which generates confidence and better economic conditions via increased activity. The improved conditions drive more confidence and attract capital, which results in greater availability of credit. The greater availability of credit broadens the universe of acceptable collateral, which generates better conditions, and on it goes.

Unfortunately, the world discovered that these highly interconnected and reinforcing five Cs can also work in reverse. So, during the bust phase of the cycle, reduced confidence led to less credit, credit contraction hurt collateral values, which hurt confidence and conditions. Deteriorating conditions further hurt confidence, which caused capital to flee, while further reducing access to credit. The contraction in credit tightens collateral standards, which further hurts conditions, and so on.

A classic example of a positive feedback loop and the role of signal strength can be found with a microphone in an auditorium. If the signal is too strong, then the speakers will generate noise sufficiently loud enough that the microphone will pick it up, with the speakers amplifying that feedback even more, generating even greater feedback, and so on. If the signal is dampened by other noises or interference of any sort, then the signal strength does not multiply. If, however, the feedback loop combines with a strong signal, the result is that utterly offensive nails-on-a-chalkboard, toe-curling screeching noise.

If confidence is the root of our signal, then the shock to one's confidence is what tips the balance and turns our virtuous cycle into a vicious one. How intensely might Mr. T's confidence have been shaken when he woke up one day and found he was effectively bankrupt? Quite seriously, I assume. How intensely might the foreign bank's confidence have been shaken when it learns that it lent money out to borrowers that suddenly appear highly unlikely to repay, even though last month those very same loans appeared quite safe? Again, one can only assume quite severely. Thus, the highly iterative and self-reinforcing loop is very reflexive and can lead the system to extremes of instability, rather than any resemblance of a calm equilibrium.

In an aptly timed essay published in Foreign Affairs at the end of 1994, Paul Krugman warned that Asia's economic success was more likely to be a mirage than a miracle. His essay, "The Myth of Asia's Miracle," began by describing the supposed economic success story of the Soviet Union. He describes how the idea of central planning and the prioritization of collective objectives over individual pursuits was considered by some as a better alternative to Western market-dominated individualism. Of course, his writing of such thoughts in 1994 after the Soviet Union had imploded upon itself was intentional.

His example provided a powerful reminder that growth by itself is meaningless, but rather, one needs to consider the sources of economic growth and their sustainability. The Soviet Union, claimed Krugman, was able to outgrow the United States in the 1950s and 1960s not because it had a more sustainable system, but rather because it had been very efficient at mobilizing inputs. Productivity, he noted, holds the key to long-term sustainable growth.

In order to fully appreciate Krugman's argument and its applicability to the East Asian story, we need to understand the basics of growth accounting. The term was first introduced by MIT professor Robert Solow in a 1957 paper published in the Review of Economics and Statistics. The basic framework suggested that there are two primary sources of growth: a change in inputs and a change in the productivity of those inputs. Inputs can further be broken down into capital and labor. Isolating each of these three variables (capital, labor, and total productivity) helps to understand how each affects economic growth.

Suppose for a moment that a country has 100 people and only one revenue-generating activity—picking apples. Fifteen of the people are too old to work, and fifteen are too young, so the working population is 70 people. Suppose on any given day, only 30 of those 70 are actually working. One very obvious way to grow the output of the economy is to have some of the 40 idle workers begin working. If the average worker can pick 1,200 apples a year, then our initial output was 36,000 apples. Now after adding additional workers (suppose another three workers join the effort), our production will grow to 39,600 apples, representing 10 percent growth. In this case, because the input of labor grew by 10 percent and output grew by 10 percent, we can say 100 percent of our growth is accounted for by labor inputs.

Now suppose we are able instead to purchase some machines (cost = 1,200 apples per machine, paid for 100 percent from savings) that help us gather more apples per worker. The machine (a handheld apple-picking arm extender that eliminates the need for climbing trees) is able to help each worker pick 1,320 apples per year. Assuming that we have added no new workers, but that each worker now has the machine, annual production will rise to 39,600 apples—exactly 10 percent higher than previously. But how can we account for this new growth, since it comes at a cost of the machines? One method is to weight the cost of the machine by the return it generates and consider that our capital investment. In our case, the machine costs 1,200 apples and generates 120 apples per year of additional production. Capital thus produced a 10 percent return. In this example, because capital grew by 10 percent and output grew by 10 percent, we can say that 100 percent of our growth is accounted for by capital inputs.

Finally, let us consider a third scenario in which our 30 workers neither get additional colleagues in the fields or new equipment to help them. Instead, they are able to grow output by simply increasing their productivity. In this case, 100 percent of the growth in output can be accounted for by efficiency gains.

Because neither capital nor labor inputs can be grown indefinitely, growth from inputs is ultimately unsustainable. Krugman argued in 1994 that the supposedly miraculous growth rates of Asia were destined to fall. They were unsustainable because they were based on growth of inputs. He highlights the case of Singapore:

Between 1966 and 1990, the Singaporean economy grew at a remarkable 8.5% per annum, three times as fast as the United States; per capita income grew at 6.6%, roughly doubling every decade. This achievement appears to be some kind of economic miracle. But the miracle turns out to have been based on perspiration rather than inspiration: Singapore grew through a mobilization of resources that would have done Stalin proud. The employed share of the population surged from 27 to 51 percent. The educational standards of that work force were dramatically upgraded: while in 1966 more than half the workers had no formal education at all, by 1990 two-thirds had completed secondary education. Above all, the country had made an awesome investment in physical capital: investment as a share of output rose from 11% to more than 40%...

Singapore's growth has been based largely on one-time changes in behavior that cannot be repeated. Over the past generation the percentage of people employed has almost doubled; it cannot double again. A half-educated work force has been replaced by one in which the bulk of workers has high school diplomas; it is unlikely that a generation from now most Singaporeans will have PhDs. And an investment share of 40% is amazingly high by any standard; a share of 70% would be ridiculous. So one can immediately conclude that Singapore is unlikely to achieve future growth rates comparable to those of the past.[261]

Similar stories, albeit less extreme, can be found across Asia. Because money was being thrown at countries like Thailand by external investors and the five Cs were in a virtuous phase, capital was easy to come by. Combined with the overconfidence developed through the prior years of spectacular economic performance, it is conceivable that money was allocated to projects with unrealistic return expectations. In an outcome that would not have shocked Austrian economists, malinvestment seemed not only likely, but inevitable.

One of the great financial industry disclaimers is that "past performance is no guarantee of future results." I've always found this statement a bit odd, even misleading. Perhaps it should be modified to "past performance is not related to future performance" or "insofar as past performance indicates a replicable skill and the future looks like the past, then we might think it possible that future results might or might not resemble past results," or something like that. In any case, just because something has happened, doesn't mean it will continue to happen. Likewise, just because something has not happened, does not mean it cannot or will not happen. In fact, underestimation of the probability of events that have not happened is a common cognitive bias. It is the natural result of employing an availability heuristic. Obviously, images and stories of an event that has not happened are less available.

Many Thai individuals, companies, banks, and government officials did not spend much time thinking about the currency mismatches that plagued their financial structures. Given the role that such mismatches played in the rapid unraveling of the economy, let us consider how the decision-making biases discussed in Chapter 3 might have affected Thai thinking.

From a psychological perspective, why were major movements in the currency not seen as possible by lenders or borrowers? Perhaps it was because the Thai currency had been very stable prior to the crisis. Perhaps it was because there was not any available data on Thai currency volatility. (Surely, however, foreign lenders would have been aware of the recent Mexican depreciation.) Perhaps they were anchored on the current ratio of ~25 baht per dollar and made insufficient adjustments for the range of likely outcomes. Might lenders and borrowers alike have thought the baht might move by ~10 percent?

There are clearly dozens upon dozens of questions that one can ask about the decision-making processes that led to the currency mismatch, but one thing remains certain—the decision to borrow in dollars while earning in baht created vulnerabilities, risks that were inappropriately considered (likely for one of the many psychological reasons discussed in Chapter 3) in the course of making that decision.

Another indicator of overconfidence (as well as excess liquidity and loose monetary conditions driven by foreign inflows) was the construction of Malaysia's Petronas Towers. The twin skyscrapers, which were completed in 1997 and almost perfectly marked the top of Asian financial markets prior to the Asian financial crisis, were the tallest buildings in the world. Chapter 11 will discuss the skyscraper indicator in greater detail.

Although there are hosts of political issues and policies that one can consider through a political lens, this section will focus on the idea of rights and prices (the two primary elements presented in Chapter 4). Let us begin with property rights, which are, across most emerging markets, less well developed than those in the United States or the "first" world. Nevertheless, property rights did exist in many emerging Asian countries, but were significantly less well protected and infringements on them less well enforced. How might individuals and companies attempt to cope with such an environment?

One way to gain greater comfort in your claim for certain property is to have strong relationships (even blood-based relationships, i.e., family) with those with whom you might end up having a dispute. Harvard University Professor Dwight Perkins summarizes the issue at hand:

Societies made up of self-contained villages or autonomous feudal estates do not have to worry much about the security of economic transactions. The village elders or the feudal lord can enforce whatever rules they choose. However, when trade takes place over long distances, local authority can no longer guarantee that a transaction will be carried out in accordance with a given set of rules.... A general authority must provide security along the road or river; each individual trader should not have to provide it on his own....

In Europe and North America, the required security was supplied by laws backed up by a judiciary that over time became increasingly independent of the other functions of government. This development of the rule of law backed up by an independent judiciary took place over centuries, and the process was well along by the eighteenth century.... There was no comparable development of this kind of legal system in East and Southeast Asia. There was, however, the development of long-distance commerce both within and between economies in Asia, and that commerce had to have something that substituted for the rule of law. That substitute drew on one of the strengths of East Asian culture: close personal relationships based on family ties, as well as ties that extended beyond the family.[262]

Thus, it seems at least reasonably likely that the lack of strong institutional structures to enforce property rights led to the mass adoption of lending based on noneconomic considerations. Perhaps the simple lack of well-defined property rights should have been an alarm bell for foreign lenders.

In terms of price considerations, perhaps the greatest government-inspired distortions took place in the currency markets. Given the export-oriented nature of most of the region's economies, most governments worked to keep their currencies cheap relative to their trading partners. The result of these efforts was an increase in the country's relative dependence on exports as cheap currencies supported exporter profits. Likewise, it hurt importers and therefore discouraged the generation of domestically oriented industries. The managed foreign exchange rates also drove, as discussed previously in the example involving Mr. T, significant currency mismatches in the financial structures of domestic companies. Thus, by interfering with the price mechanism's efforts to determine the price of a currency, many Southeast Asian governments magnified their vulnerability to currency volatility.

Our epidemic lens provides little value here. As is evident by the now common reference to the East Asian financial crisis (not boom or bubble), the story here is really one of a bust. Sure, stories exist of property prices and stock prices going through the roof, but there are few stories of taxi-drivers, housewives, and gardeners investing in the market. Rather, it was a story of global capital flows (some might argue "hot money") that filled the void and provided the fuel for the boom to take place.

The emergence lens, however, does provide insight. As we found in our study of the Japanese boom and subsequent bust, Asian philosophies tend to be less individualistic and more communal. They emphasize social harmony and group cohesion over individual pursuits. The impact of this pack mentality is that markets become highly tippable in one direction or another. Just as was discussed in the previous chapter about Japan, so too is the swarm/herd framework applicable with respect to Asia. We won't recount the same logic here, but it might make sense to review Chapter 8 in light of the East Asian scenario. It will seem eerily pertinent.

Another "herd" that emerged during the early 1990s was the group of fund managers focused on emerging markets. Inherent in their design as diversified managers was a linkage and coupling of very different economies into one bucket. Further, given they merely allocate other people's money, these fund managers became herdlike in their behavior because of client flows. Thus, in good times (think early 1990s), flows into their funds would likely be positive and the herd would stampede in—bringing capital along. However, if the herd changed direction, the stampede would occur in the opposite direction, with capital flight from the country.

Table 9.1. The Five-Lens Approach to the Asian Financial Crisis

Lens | Notes |

|---|---|

Microeconomic | Pro-cyclical capital flows Reflexivity of confidence |

Macroeconomic | Hot money inflows providing cheap capital Financial innovation (finance companies to hide leverage) Moral hazard motivated lending |

Psychology | Anchoring on currency values, insufficient adjustment World's tallest skyscraper (Petronas Towers) New era thinking ("miracles" and "tigers") |

Politics | Crony capitalism inspired moral hazard Political focus on undervalued currencies |

Biology | Silent Leadership (communal philosophies) Herd of emerging markets funds |

In discussing the Asian crisis, Michael Lewis described this phenomenon bluntly: "The collapse of the Thai baht in July 1997 caused the people who had invested in places that reminded them a bit of Thailand (South Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia) to take their money and go home."

Given the East Asian financial crisis was really a set of many different crises that fell like dominoes, this chapter attempted to focus on the case of Thailand as representative of the situation. The five-lens approach to thinking about the events that unfolded yields some striking similarities to other booms and busts. Table 9.1 provides a quick summary of the chapter via the lenses discussed.