13

Blueprint your Structure

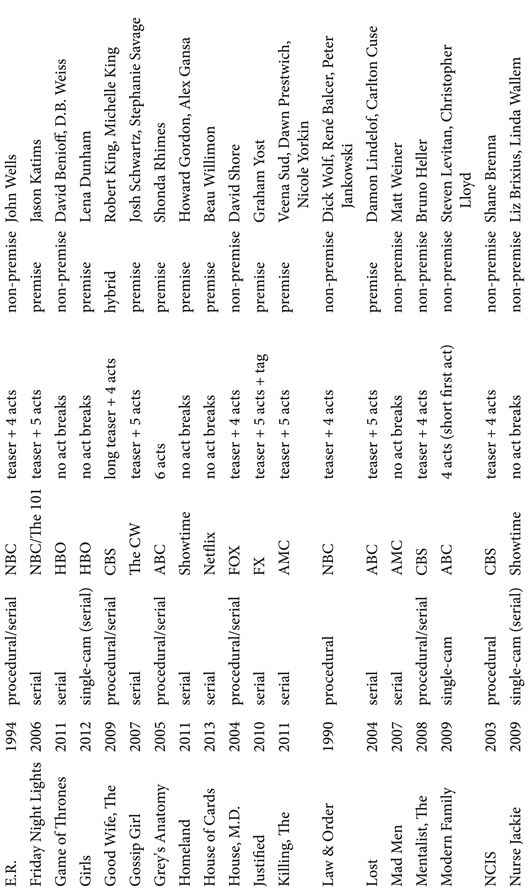

Television scripts vary in numbers of acts depending upon the type of show—sitcom, one-hour drama, single-camera dramedy, MOWs (“movies of the week” made for television), and so on. Broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and FOX) and basic cable networks (such as AMC, A&E, FX, TNT, and USA) are supported by advertising, with commercial breaks interrupting the drama or comedy. Premium cable networks (HBO, Showtime, and Starz) are subscriber supported and have no commercial breaks.

Up until about ten years ago, virtually all sitcoms were two acts and all one-hour drama series were structured with four acts. In 2013, these basic templates have changed in order to satisfy network programming, advertisers, and viewers’ shorter attention spans.

It’s not difficult to predict where this is all going as more viewers are watching their favorite shows online—via computer, iPad, smart phone— thus enabling them to skip over commercials. “Binge viewing” is also becoming more prevalent. House of Cards premiered and made available its entire first season simultaneously. Over the next few years, we’ll start seeing fewer commercials and more product placement or embedded advertising (as part of the content of a show). And eventually, you’ll be able to “like” an item of clothing or accessory, “click” on that item while the series is playing, and immediately be linked to a website to purchase the items—all with a stored credit card and another click on your mouse or remote. Before you know it, a TV set will become as obsolete as a typewriter or VCR. Your computer will be your window to all entertainment. Stay tuned.

Structural Formats

Each show fits into a particular format that allows it to be easily identified. Dramas are generally classified as either procedurals or serials. Procedurals, such as Law & Order, CSI, The Mentalist, and House, M.D., deal with a new case each week. At the end of the episode, the cops will catch the bad guy, the lawyers will win their case (or not), or the doctors will save their patient (or not). Even though procedurals are much more plot-driven, sometimes they break format and deal with more personal stories. In the season 6 finale of Law & Order titled “Aftershock,” the entire episode showed how the cops and lawyers spent a personal day after witnessing an execution, a big departure from the follow-the-string, investigatory backbone of the series.

Serials contain more complex storylines that span multiple episodes or even seasons. Most serials use a direct pickup (or DPU) in which each new episode starts exactly where the previous episode ended (examples: Weeds, House of Cards, and the latter part of season 2 of Scandal).

Other serials, such as Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and Homeland, are looser and begin new episodes in what might be the next day or week or month. Mad Men jumped ahead a year between seasons. Season 5 of Desperate Housewives made a quantum leap five years after the previous season and used flashbacks to bring the audience up to speed.

In the first season of The Wire, the cops’ mission is to arrest drug kingpin Avon Barksdale (Wood Harris), but they don’t even know what he looks like! It’s not until the third episode that the police are able to locate an old photo of him. In a procedural where plots move much quicker, Avon would have likely been captured in one or two episodes.

Comedies are generally classified as either multi-camera or single-camera sitcoms. Multi-cam sitcoms, the more traditional format, are filmed (but usually videotaped) with four cameras running simultaneously on a stage in front of a studio audience, for example, The Big Bang Theory, 2 Broke Girls, Friends, and Two and a Half Men. (I Love Lucy was one of the pioneers of this format, with Desi and Lucy shooting each episode in chronological order for a live, in-studio audience to enjoy each episode like theater.) Many classic sitcoms (Taxi, Cheers, Happy Days) were shot on 35 mm film for a rich, movie look, but that’s a rarity in 2013 due to efficiency and expense.

Single-cam sitcoms such as The Office, Modern Family, and 30 Rock, employ one camera and tend to shoot more characters, scenes, and locations. Single-cam shows are more prevalent today.

To wrap your brain around the difference between multi-camera and single camera sitcoms, here’s an example I like to use.

On a multi-camera sitcom, we’re generally inside one of two or three main locations: the hangout/workplace, the apartment/house, and one “swing set” (optional interior location) depending on the story. If a character on a multi-camera gets mugged in the park, he will rush into a room out of breath, very distraught with ripped clothing, and explain to whoever’s present what just happened.

On a single-camera sitcom or dramedy, we would probably get to go outside to the park and see the mugging take place, along with the chase, and maybe even the race back to the apartment where he would then recount the story but with far less detail because we would have already seen it—unless it’s revisionist history for comedic effect.

Multi-camera sitcoms are more contained and primarily shot indoors on the same sets week after week. We come to view these places as familiar and iconic. The bar in Cheers was our bar, too. In fact, for the first two seasons of Cheers, we never left the bar. We went into the backroom, Sam Malone’s (Ted Danson) office, and maybe a bathroom or alcove. There were stairs leading up to a restaurant above the bar, but we didn’t actually go there for many seasons.

Single-camera comedies and dramedies (Modern Family, Louie, Parks & Recreation, Weeds, Girls) take us everywhere: inside, outside, up in the air, in the ocean—wherever the story needs to go, we get to go there as well. Animated comedy series (The Simpsons, Archer, Family Guy) can take us anywhere the writers can imagine without limitation; if it can be drawn, it can be done. There is also the hybrid sitcom, which blends multi-cam and single-cam characteristics, such as How I Met Your Mother.

The ABCs of Episodic Structure

The A Story

Primarily services the central concept of the series—known as the franchise. This dominant plotline concerns the principal character(s) and contains the most scenes (or “beats”) within the episode. The franchise also serves as the signature—or “sweet spot”—of the series, and offers the most possible evolving plotlines (known as story engines) from episode to episode.

In The Mentalist, the A story revolves around Patrick Jane (Simon Baker) using his exceptional powers of perception and persuasion to help the California Bureau of Investigation solve a case.

In Dexter, the franchise usually deals with vigilante serial killer Dexter Morgan (Michael C. Hall) hunting a vile criminal who eluded justice.

In the sitcom Arrested Development, the A story typically consisted of Michael Bluth (Jason Bateman) attempting to keep his eccentric family afloat after his father plunges the family into financial ruin by committing fraud.

The B Story

If the A story services the case and higher external stakes, the B story is usually a personal story, with more internalized, emotional stakes. The B story serves to make the main character relatable and vulnerable.

In Castle, Richard Castle (Nathan Fillion) is a multi-millionaire playboy crime novelist who shadows NYPD detectives to get research for his next book. These A stories involve mystery, suspense, and danger. However, he’s also a devoted family man, providing for his mother and teenage daughter who both live with him. The B story concerns Castle’s interactions with them.

In Sons of Anarchy, Jax Teller (Charlie Hunnam) is one of the leaders of the felonious Sons of Anarchy motorcycle club. While the franchise deals with club business (murder, trafficking, etc.), the B story follows Jax’s relationship with his girlfriend/wife Tara (Maggie Siff) and his two young sons.

Runners. Shows may also contain less significant C and even D storylines called runners. They might consist of a semi-trivial conflict that’s secondary to the franchise, a personal story involving the supporting characters, or a running gag. In a recent episode of Mad Men, Peggy Olsen’s (Elisabeth Moss) apartment is invaded by a big rat. She struggles throughout the episode to get rid of it. But when the pesky rodent gets caught in a trap and leaves a bloody trail, Peggy desperately calls coworker Stan (Jay R. Ferguson) in the middle of the night for help—even offering him sexual favors in return, but Stan is in bed with another woman and declines. By the end of the episode, the rat problem is solved when Peggy gets a cat. Actually, we don’t see her acquire the cat; it’s just sitting beside a much calmer Peggy on the sofa at the end of the episode—a good example of elliptical storytelling (telling the story “in the cut”). Other Mad Men runners include Don and Betty’s daughter Sally’s (Kiernan Shipka) crush on a teenaged neighbor boy; Don’s new actress wife Megan’s (Jessica Paré) blossoming soap opera career; Pete’s (Vincent Kartheiser) brazenly senile mother. And what about mysterious new colleague Bob Benson (James Wolk)—who may or may not have a crush on Pete—or is he just a passive-aggressive opportunist?

Serials often have several runners because there are more characters to service. In the pilot for The Sopranos, Tony (James Gandolfini) passes out from a panic attack during a backyard barbecue, and soon thereafter begins therapy with his psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi(Lorraine Braco). Meanwhile, Tony’s wife Carmela (Edie Falco) and their daughter Meadow (Jamie-Lynn Sigler) grow further apart; Tony tours an assisted living community with his overbearing mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand); and Tony has a tryst with his mistress. On The Sopranos, the A story is usually a mafia crime story that begins and ends with Tony; the B story is usually a personal domestic Sopranos story; and the C and D runners might involve Tony’s nephew Christopher Moltisanti (Michael Imperioli), or sister Janice (Aida Turturro), or Uncle Junior (Dominic Chianese) or a more personal story about one of his other relatives.

In a subsequent episode, Dr. Melfi’s personal life becomes more prominent as she starts seeing her own therapist. In a powerful memorable story arc, Dr. Melfiis raped in a parking garage, and even though she would like nothing more than to tell her client, Tony, about her ordeal so he could hunt down the rapist and exact revenge, she maintains her professional distance and keeps her secret. This is also a good example of how the path of characters from different spheres can intersect in surprising or even shocking ways—which leads us to…

Crossover. A, B, and C stories are clearly delineated, but sometimes they intersect. In the two-part season 5 finale of CSI (co-written and directed by Quentin Tarantino), the “case of the week” becomes personal when Nick (George Eads), one of the crime scene investigators, gets kidnapped and buried alive. In The X-Files, sometimes the paranormal “case of the week” deals directly with Fox Mulder (David Duchovny) and his personal journey to find out what happened to his sister whom he believes was abducted by aliens. In The Mentalist, some of the cases lead Patrick one step closer to finding “Red John,” the notorious serial killer who murdered his wife and daughter years earlier.

Sometimes B stories or runners become bigger stories. In Burn Notice, Michael Westen (Jeffrey Donovan) is a former CIA agent who was framed as a rogue spy. The franchise deals with Michael and his friends (an ex-Navy SEAL and a former IRA member) utilizing their training to help people get out of dangerous situations. The B story tracks Michael’s quest to find out who framed him and why. However, there are a few episodes which deal primarily with the overarching mystery of who “burned” Michael.

In Terriers, private investigator Hank Dolworth (Donal Logue) tells his partner Britt (Michael Raymond-James) that he thinks he’s losing his mind because sometimes things are randomly out of place in his house. It’s a runner that begins as passing dialogue, but then escalates when the audience learns someone is sneaking around his house at night. The runner grows again when the mysterious person is revealed to be Hank’s schizophrenic sister Stephanie (Karina Logue) who’s been secretly living in his attic. The runner grows yet again when the audience discovers that Stephanie is a brilliant MIT graduate who helps Hank solve the big mystery of the show.

In Breaking Bad, DEA agent Hank Schrader (Dean Norris) tirelessly searches for the mysterious meth dealer Heisenberg, who is actually his brother-in-law Walter. The storyline of Hank and Walt’s ironic relationship has its peaks and valleys…until [SPOILER ALERT] mid-season 5 when Hank gets wise to Walt’s alter-ego.

Storyline intersections work best when they occur with thematic links. In Burn Notice, Michael helps people who’ve been wronged while he attempts to rectify the injustice done to him. Family is always a strong thematic link. In The Sopranos, Tony must balance his mob family and his actual family. In Sons of Anarchy, Jax must balance his biker gang family with his actually family. In Modern Family, different portraits of nuclear families deal with similar issues.

Tentpoles. Within these format and pilot guidelines exist various structural models. Each model has a different number of tentpoles, which are teasers, act breaks, and tags (a very brief scene/sequence at the end of the episode). Dramas can be four acts, five acts, six acts or even longer (sometimes pilots are extended to properly set up the show), with or without a teaser and a tag. Comedies can be two acts, three acts, or four acts, with or without a teaser and a tag.

The teaser sets up the hook. The first act establishes the problem that the main characters will face. In the middle acts, the problem complicates, the stakes intensify, and the solution seems impossible. In the final act, the story reaches its climax and resolves. The tag is as an epilogue that puts a button on the episode. It may be a runner that pays off, or it could be a cliffhanger that services the franchise or the B story.

Each act generally has four or five beats, and ideally ends on the A story about the main character’s dilemma. The franchise (A story) tracks throughout every act, while the B story and runners can be sparse. Occasionally, you might elect to end an act on a potent B story. It’s extremely rare to end an act on a C story. If the story is worthy of an act break, then it’s not your C story—it’s probably more of your A or B story.

In the pilot for Breaking Bad, {the teaser} opens with Walter White’s madcap dash through the desert in an RV-turned-meth lab. Amid the growing sound of sirens, Walter prepares himself for a police confrontation {the hook}. Act 1 jumps back three weeks earlier to orient the audience in Walter’s normal world. He’s turned fifty years old, he has a pregnant wife, a teenage son with cerebral palsy, and he needs money {the problem}. He supplements his high school chemistry teacher salary by working at a carwash. His problems complicate when he’s diagnosed with terminal cancer {problems and stakes intensify}. Now Walter needs money for his family before he dies. After watching news footage of a DEA meth lab drug bust worth $700,000, Walter asks his brother-in-law Hank if he can go on a ride-along so he can surreptitiously learn how a drug operation works. During the ride-along, Walter encounters Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul), a former student of his who narrowly escapes a DEA raid. Walter convinces Jesse to team up. “You know the business, and I know the chemistry.” Walter and Jesse cook meth, but they have no distribution in place. Jesse goes to former partners in crime to sell the product, but the former partners think Jesse double-crossed them, so they intend to kill Jesse and Walter {impossible solution}. Walter improvises and kills the former partners in the RV with a chemical mixture. A fire begins to rage in nearby shrubbery because one of Jesse’s former partners had tossed his cigarette out the window. Walter drives the RV as far away from the fire as possible, which brings the episode full circle back to the teaser. As the sirens approach, Walter discovers the sirens were from fire trucks racing toward the blaze created by the cigarette, not police cars {climax}. Jesse and he are off the hook—for now {resolution}. The pilot wraps up with Walter withholding information from his wife about his new business as well as his cancer. This sets up the rift that slowly grows in his marriage {the epilogue1}.

The franchise is Walter building his drug business. The B story is Walter’s struggle to balance family life with his secret enterprise. Some of the runners include Walter dealing with his cancer, gleaning (and hiding) information from Hank, and working with his impetuous new partner Jesse.

Some showrunners of premium cable series still use act breaks in their scripts—even though there will be no commercials. Why? Because writing in act breaks can be highly beneficial to telling a story that’s at once riveting on the plot level and fits in the allotted time slot. Pick up a script from the HBO series Deadwood (created/written/showrun by David Milch) and you’ll see four clearly delineated acts. On the other hand, examine a script for the Showtime series Homeland and lo and behold: no act breaks.

Here’s a quick, random sampling of different structural breakdowns.

One-Hour Dramas

Breaking Bad: teaser + 4 acts

CSI: teaser + 4 acts

The Good Wife: long teaser + 4 acts

Grey’s Anatomy: no teaser. 6 acts.

Justified: teaser + 5 acts + tag

The Mentalist: teaser + 4 acts

Once Upon a Time: no teaser. 6 acts.

Parenthood: teaser + 5 acts

Royal Pains: 7 acts

Scandal: 6 acts. Short first act functions as teaser, followed by title card.

Sitcoms

The Big Bang Theory: cold opening + 2 acts + tag

Modern Family: 4 acts (short act one functions as a teaser)

Two and a Half Men: cold opening + 2 acts + tag

The Teleplay: Basic Guidelines

Most half-hour, multi-camera sitcoms are written in double-spaced sitcom format and run around fifty pages.

Most half-hour, single-camera comedies and dramedies are written in single-spaced screenplay format and run approximately thirty pages.

Most one-hour drama series teleplays run between forty-eight and sixty-three pages. However, many pilot episodes run longer and then get cut down during the production process, especially in post-production. Teleplays for Moonlighting, The West Wing, and E.R. could run eighty-five pages or more due to their fast pacing and rapid-fire dialogue. But even at that higher page count, the produced show would fit into its one-hour time slot.

It’s not always easy to gauge the actual length of an episode until it’s shot. The rhythm of the actors’ deliveries, the pacing of scenes, editing styles, and musical interludes (such as on Glee) can impact actual length versus page length. For this reason, once a show is up and running and becomes a well-oiled machine, a series’ script supervisor will read the script and do a “timing” or estimate of the actual length of the episode. For a writer who’s trying to sell an original pilot script, it’s usually best to work within the basic page length guidelines (see “basic guidelines”). Aaron Sorkin gets to break the rules and do his own thing because he’s won Emmys and Oscars and is a genius.

When writing a pilot for a sitcom or one-hour drama, I advise you to study current, successful series that have the same tone, rhythm, and pacing that you’d like your series to have—and study the structure. Does it use a “teaser”? How many act breaks? How many scenes per act? Is there a “tag” or epilogue?

For script formatting—that is, how the words need to look on the page, line spacing, indentation, pagination, please read as many teleplays as you can and emulate the script format. I also recommend an excellent book that delves into this area with specific examples: Write to TV by Martie Cook.

Writing a teleplay without an outline is like going on a road trip without a map. But, in the TV biz, the schedule necessitates the most direct, expeditious route. If you’re hoping to succeed as a TV writer, learn to embrace the outlining process; it’s not only a valuable GPS to keep your script on track, but it’s also compulsory (for the studio and network to sign off on the script). No outline, no paycheck. Never bite the hand that feeds you.

Glen Mazzara Credits

Best known for:

-

The Walking Dead (Executive Producer/Writer) 2010–2012

WGA Nominated (New Series) 2011

- Hawthorne (Executive Producer/Writer) 2009–2011

- Criminal Minds: Suspect Behavior (Consulting Producer/Writer) 2011

- Crash (Executive Producer/Consulting Producer/Writer) 2008–2009

- Life (Co-Executive Producer/Writer) 2007

- The Shield (Executive Producer/Supervising Producer/Co-executive Producer/Writer) 2002–2007

- Nash Bridges (Writer) 1998–2000

NL: The Walking Dead is based upon comic books. In plotting your series, how much are you basing on the source material, and how much are you inventing?

GM: We invent most of the story we have here whole cloth. We crib major characters and plot points or settings from the comic books. So, for example, in the upcoming season, we introduce two major settings: one is the prison that Rick (Andrew Lincoln) and the core group of survivors we’re following discover and decide to take over and set up shop there. There are two major characters that are being introduced. One is Michonne (Danai Gurira) who is an African American woman. We consider her a soldier. She carries a Katana sword and she’s a fan favorite. So we’ve now worked her into the show.

We also have The Governor (David Morrissey), who is an arch villain in the comic book and he is the leader of a walled community called Woodbury. Our version of The Governor is very different. Our version of Michonne is very different. The way our characters are introduced. What they say. That’s all original to the show. We are doing our takes on these characters because we feel the fans want to see those characters dramatized, but we really make that material our own.

NL: In season 1, the first six episodes move very quickly. It seems like each one was almost like a feature film, and as much as I liked it, I thought it might be difficult to sustain that. So my next question is about pacing. How do you gauge the pace of the storytelling?

GM: That’s a great question because I think when the show first came out I was only a freelance writer that first season. I think there was a need to tell as much and to grab the audience because they only had a six-episode order. When we went to thirteen for the next year, we decided to slow down the pace and push in to examine some of the characters’ lives. This show developed into a character-driven cable drama that fit nicely into that paradigm. However, there’s a larger audience wanting to watch the show and those are horror fans and comic book fans. It’s a lot of youth. We have a much more eclectic audience than the typical cable drama audience. So when I became showrunner in the middle of season 2, my natural tendency was to put more story in. This is something that I really learned on The Shield and the first show I started on, Nash Bridges, where I was writing partners with Shawn Ryan. And Nash Bridges became a great training ground for other showrunners: Shawn and Damon Lindelof. So I wanted to move up the story and pack it in. At the time we started doing that in the second half of the season, we were airing the first half of the season, while we were already shooting the second half. And the feedback from the audience came in that it was very frustrating, frustratingly slow. That pacing was not something that the audience was responding to.

So when the second half of the season came out and I was responsible for all of those scripts, it seemed to answer an audience need, but we were already ahead of the audience. I believe we were responding to something we felt slowed the brakes on a little too much. I think we had to define what is the story we’re telling. We’re talking about an apocalypse. We’re talking about a civilization. We’re talking about desperate survivors. So the stakes are higher than a living room drama, and we were doing a little bit too much of a living room drama. So we started increasing the pace, and by the end of the season, it was pretty much where I wanted it to be. Moving forward, it’s interesting because I do want to pack a lot of story in and the risk is that you reach a tipping point where it’s too unrealistic or too fantastic or too shocking for the audience. It’s my job as a showrunner to say what is too much. I have to go with my gut. We do have episodes that I describe as a pool in a rainstorm, it’s just about at that level, but it’s not spilling over yet. I feel that it’s my job to both push the material and to make it exciting and surprising and satisfying the horror element which is unique to this show. This is the first show that I’ve worked on with a horror element. And yet, you want it to stay grounded and for it to feel real. This is really a debate that I have every day with our cast, our directors, our producers, and our network and studio, AMC. I would say that is one of the biggest challenges of my job right now.

NL: It’s a balancing act.

GM: Right. And the way I approach that is that I do have an overall arc for the season. But I focus on each individual episode and there are elements that I want to have associated with the show or incorporated into the show, but I can’t fit every thing in every episode. So instead I have sixteen episodes where some episodes can be a little more character focused and others could be a little more horror focused or action focused. Some could have some comedy. By the end of the season, I think the total experience will be satisfying.

NL: How vital to you is an overarching central mystery? Because in season 2, you had a few mysteries going. You had “What happened to Sophia (Madison Lintz)?” You had “What did Dr. Jenner (Noah Emmerich) whisper to Rick?” Etc.

GM: In a genre show like this that has a horror and science fiction element, the fans in the audience are very, very interested in mysteries. They want to know the rules of the game. They want to be convinced that this is a worthwhile ride. That the end of this experience will be satisfying. And there have been other genre shows that have not necessarily delivered a satisfying experience and that is disappointing to a very, very dedicated fan base. I’m aware of that. However, I am not that type of a writer. I don’t feel that the mysteries are why people watch TV. Because my bottom line rule of TV is that it’s cool people doing cool shit every week. That’s it. Let’s break down that sentence. Cool people doing—doing—cool stuff every week. Not learning cool stuff every week. They need to be active. To have their backs against the wall. To be in dire straits. They need to made desperate choices. David Mamet says that drama is basically a decision between two horrible choices. That is certainly something that we use on this show. I’ve worked on a number of other TV shows in which writing staffs try to go for the big payoff and revelation. That only works sometimes. I actually think there’s too much emphasis on revealing the answer to a mystery as being satisfying to an audience. We didn’t do it on The Shield, I’m not really interested in doing it here. For example, “What caused the outbreak?” is a question that people ask a lot. Who cares? That’s not part of the original comic book. So, what do you do with the information that you have? If you look at the episodes in the back half of season 2, I think that that’s important. That’s the type of storytelling that I’m very interested in.

Let’s look at the major revelation of season 2 that Sophia’s in the barn. Sophia steps out of the barn. We could have stopped the show there. Instead everyone is paralyzed by the horror that she was right under their noses and Rick, who doesn’t know what to do, steps forward into a leadership position and does what no one else is able to do. This revelation led to character action and then the show ended. So to me, that was a scene of character action, not revelation.

NL: What about the role of theme? The first six episodes seemed to very much be about the theme of survival.

GM: Yes.

NL: In season 2 what emerged for me were the themes of hope and faith. There’s a whole episode where they go to a church. Then there’s thematics where the A, B, and C stories connect. How aware and deliberate are you about thematic links between the stories?

GM: When we are trying to achieve something artistic, you let some type of energy or spirit flow through you. You have to be able to listen and you let the work reveal itself to you. And the minute you try to inject your ego into that, it actually screws things up. The Walking Dead is the first show for me where theme is important as we’re developing it. On other shows, particularly The Shield, the theme became apparent very, very late in the game. When we sat down to break season 3, we had some ideas and I had some larger themes that I wanted to examine. When I pitched it out to all of the other, non-writing producers and then to AMC, I did approach it thematically and usually when I’ve done that, it usually feels like horseshit. It feels like something I’m just telling an executive so that get what box the show is in. But it turned out to be true and there were certain themes on season 3 that we keep coming back to. It just works. What we try to do is focus on the story, and then when we step back, we see that the theme is there. And now we have confidence in the story. We do not try to construct the story to fit the theme.

We broke this season in detail for eight episodes and then we went off and wrote them. And then when we came back in to fill in those next episodes, the theme still applied and was still connecting. We’ve had two themes for this season, and they’ve both been very necessary lifelines to get through all the confusion of the daily making of the show.

NL: Are Rick stories always going to be your A stories?

GM: There are different forms to tell a TV story. And in an ensemble piece like this, you’d usually have the Rick character as the A story, someone else would be the B story, and someone else would be the C story and then you would intertwine those stories. That doesn’t always equal a theme. It just pushes the ball further on each one. That is the case with Game of Thrones. When you watch an episode, you watch an installment where all of your characters advance, but that episode may or may not be a total story within itself. We do have elements of that A, B, C story here, but I think for the most part we reject it. I think we look at each episode as having a beginning, middle, and an end—and whatever fits to that theme for that episode. For instance, the episode when the girl steps out of the barn and when the herd overruns the farm at the end. Each character has a place in that larger story. This is the first time I’ve ever worked on a show that’s rejected the traditional A, B, and C story format—and gone for more of just “What is this episode about?” What gets lost in that is perhaps the opportunity to examine particular characters. Sometimes minor characters just stay minor characters. That’s a risk, but I feel the story drive of the engine is strong enough that it will be satisfying to the audience.

NL: In season 2, you started to introduce some flashback elements.

GM: When I joined the writing staff, there was a tendency to try to embrace those flashbacks. I have rejected those flashbacks, so in the episodes where I’ve been a showrunner—and I’m open to doing flashbacks—but I’ve rejected them here because I don’t believe that flashbacks are an element of horror films. They’re an element of science fiction films. When you introduce flashback, you start playing with the space-time continuum. I think it takes you away from the visceral and immediate horror. At the end of the day, I feel that The Walking Dead has to be a horror show—that’s what’s unique about it. I don’t find flashbacks scary. They were just giving more information or explaining the rules. Part of the difference between the first half of the season and the second half is that I focused on the horror elements.

NL: If you’re not identifying things as A, B, and C stories, what’s the process of doing outlines and beat sheets?

GM: I don’t use outlines. I’ve been taught to react or follow my gut from reviewing a written script. An outline is an interesting tool, but I can’t shoot an outline. It’s really about the script and the execution of the script. I really feel like outlines take up a lot of valuable writing time and that they are used to engage TV and studio executives. So that they can cover their asses and know what’s being written. None of their notes are applicable to script. So we write a two- to three-page story document and send it over to the network. It’s written in paragraph form. It’s what we’re going for in the episode and what the major set pieces are. I leave it to the individual writer to write it. What I do is work offof the beat sheet, I can work offof two or three words per beat. For example, “Rick kills Shane.” I don’t need to flesh that out. All script problems, for me on The Walking Dead, come down to structure problems. But if the structure is right and you start in a linear fashion, I have confidence in the writing staff that we can execute it. There was one scene I wasn’t happy with and I went back in to re-beat it and discovered that it was a structure problem. And a beat sheet for me is a piece of scrap paper with ten words.

NL: In the pilot episode, there weren’t any act breaks. It was regular screenplay format. But now you’re using four acts, correct?

GM: We use five acts actually. They split us into a teaser and five acts. There were four acts—good catch. AMC wanted an additional commercial break. Let me say this though, I absolutely love TV. I’m a student of TV. I loved TV when I was a kid. I’m more of a TV guy than a film guy. So when I first joined the show, those act breaks were not important, and I feel that those act breaks are an important part of the viewing process. What do you go off of?

I learned this from Nash Bridges and Th e Shield, which had very, very good act breaks. It forces you to make choices. It’s about compression. We pack in a tremendous amount of story into forty-two minutes. People have that expectation, and yet you don’t want to do it in a way that it feels like an assault—you need breathing room.

Look at our season finale last year [in 2011], there was a huge zombie attack in the first half, and yet in the second half, there was very little zombie stuff except for Andrea (Laurie Holden) in the woods. That’s very different, so you really have to make all those act breaks count.

I do find that TV shows that embrace the TV form embrace the act break. There are some people who say, “Our TV show is not really TV. It’s like making a film every week.” Which I find disparaging to the art of TV, and I could certainly say if you look at all the great TV shows on TV today, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, Homeland, hopefully, The Walking Dead, and you count the total number of hours that those shows produce, you’ll probably come up with seventy or eighty hours. In turn, name fifty feature films this year. So the action is all in TV right now, it’s all in TV. And yet, there’s this snooty attitude in TV that when it’s good, it’s rejecting itself as TV. “It’s not TV, it’s HBO.” No, it’s TV and it’s very well done.

People really, really care about this show. They feel emotionally invested. So much so that they cry when our characters die. But name a horror film when you cried when a character died. That doesn’t happen. You never cry in a horror film.

NL: What are the biggest challenges of running a show?

GM: I’m sure a lot of people tell you time management. I don’t think that’s necessarily true. I think one of the biggest challenges for me is to not settle. There are a lot of people, including myself, I have fifteen producers on this show. They’re all talented. They’re all smart. Some write, some don’t. They all have strong opinions. It’s hard for me to get fifteen people to agree. It’s hard to listen to all of their notes. I have a very open door policy, in which I invite everyone’s notes, from the cast, from the director, and hopefully, I get a lot of input while the script is being written and I can then use the best ideas. It’s hard to (1) not take a barrage of criticism and feedback personally and (2) to make sure that everyone feels heard and yet not lose my vision as the showrunner by trying to make everyone else happy. I still have to realize that I have to be the singular vision for the show—that’s my job and that’s how the show will hopefully be successful. The rule that I’ve been following is that I only do something if I love it. If I absolutely love it, I believe it will work, and right now, I’m in that position. I think in the past on other shows, I tried to be too amenable to other people, too accommodating, and perhaps I didn’t stick to my guns. But you never want to be a tyrant or a dictator or shut down someone else’s creative voice.

The other challenge is to keep the show grounded—to keep it real. And yet, to deliver something that has a horror element. Part of horror and science fiction is that there’s a sense of high adventure. You want action, but you never want it to tip over into something unreal or ludicrous. If you have a clear direction, all the other stuff works itself out. And you go for a vacation at the end. Showrunners don’t sleep.

NL: Do you do a polish or a final pass of each script?

GM: I do an extensive polish on every script, if needed. There are many times that I will say I write a lot of each script. I don’t put my name on it. I have several scripts this year that I’ve written every word of and have not put my name on them. I have an executive producer credit on all of those. It’s my job as the showrunner. When I first became a showrunner on Crash, I didn’t rewrite some of the writers because I liked them. But then, I realized that part of my responsibilities as a showrunner is to be the voice of the show. So if a show comes out and it’s not necessarily my voice, the producers, the cast, and the crew might feel that it’s off. So no matter how well written—we do have a very, very talented writing staff. I’m very proud of them. But I also have a very specific thing in mind. I also try to push the material. I very often write stuff that people don’t think is going to play because I have a very stripped down writing style. So when people read it, it feels sparse and a little awkward and yet what I’m doing is writing directly for camera. I write the way I know the scene is going to be edited. So when you read my writing, you say, “Wow, I saw that.” You see everything there—including the silences and the looks from the actors. I’m writing less and less dialogue. I’m just letting the picture tell the story. I’ve gotten better at suppressing my ego and letting the story reveal itself through the writing.

One of the scenes I was really happy with is when Rick finds Carl (Chandler Riggs) sitting in a hayloftand he gives him a gun. He says, “I wish I had more to say, my dad was good like that.” You just get a whole sense of who this man’s father was. We know that Carl has lost his grandfather and that Rick is an inarticulate hero. And he gives him a gun which ends up being the gun that will kill Shane (Jon Bernthal). It’s a very underwritten scene, and if you look at how it’s filmed, we just set up a camera. Man enters frame and sits next to his son. Push in for a little coverage and get out. It’s very simple. On the page, when you read it, it might read a little flat, but then when it comes together, it plays, it’s right. I’m very careful not to overwrite, particularly on this show where things can get overwritten.

NL: What’s the best thing about being a showrunner?

GM: I have two answers. One, I realize how lucky I am and that I have a great giftin the sense that I get to do what I want and tell stories and work with talented writers and directors and that some studio puts up millions of dollars to make each episode. There are so many filmmakers and artists around the world trying to figure out how to do their art. I can’t take that for granted. I get to come to work every day and whatever I am passionate about will get made right now. And that’s very, very exciting. So I see being a showrunner as a gift. Last week, I went to Atlanta and I screened our season premiere for the cast and crew. Everybody cares so much about this show. Every part of the organization just loves The Walking Dead. And I’m the one person in the entire organization that gets to see everybody else do their best work. So I get to see the writer who’s excited about the fact that they found a great scene or they’ve got a great pitch. I get to see the casting agents excited because we got the perfect person. I get to see the director excited and the cameraman excited because he’s going to get the best take. And it goes all the way through special effects and the music. The composer, Bear McCreary, is fantastic. It goes all the way to this little studio at Warner Bros.—this little sound mixing room— and you walk in there and there are three guys and they say, “We just love this episode. It’s the best show we’ve worked on.” And they’re so excited. I’m the only person who gets to go through the whole process from inception to completion. That’s really special. That’s what’s unique about being a showrunner.

Note

1 In a sitcom, the epilogue is known as the “tag.”