Introduction

Financial resources can be managed, and are managed, to good effect. Physical and technological resources can likewise be managed to good effect and so can human resources. Human resources are composed of individuals working for an organisation, employed these days on a variety of contracts, some as ‘core’ long-term staff, some as temporary staff, some as contracted staff, but collectively making up the most important of an organisation’s resources. People are the only resource that can put financial, physical, and technological resources to best use. Managed well, success should follow; managed badly, failure will sooner or later result. To describe people as resources is not to dehumanise them, as some have asserted, but to recognise that they are valuable, and therefore should be treated as human beings. Old-fashioned terminology such as ‘labour’ or ‘personnel’ unfortunately did not always command such respect.

The first edition of this book, as outlined in the original preface (1980), sought to pioneer the idea in Britain that employees could and should be managed as a valuable resource. Today most managers are comfortable with the term ‘human resources’. A few still prefer to refer to ‘people’ or ‘employees’ or ‘staff’, and to use the term ‘personnel management’. At one level the terminology is less important, because it is practice that really counts. But at another level it does matter because ways of managing people at work have come a long way in the last 15 years, and a refusal to use the modern term ‘human resources’ can be an indication of a failure to recognise and utilise recent developments. A greater danger lies in the adoption of the new terminology while sticking with outdated policies and procedures, and too many examples of this arc still to be found in companies today.

The term ‘human resources’ gained popularity in the United States some 15 to 20 years ago, and subsequently crossed the Atlantic a few years later. Recognition in the United States by leading organisations and writers on management of the importance of the contribution that could be made by employees to achieving corporate goals (including in the case of ‘for profit’ organisations to market share and the ‘bottom line’, and in ‘not for profit’ organisations to the quality of service), created great interest in new ways of managing people at work. This interest was heightened by an appreciation of the attention paid by Japanese corporations to employees and corporate value systems,1 and evidence that the most successful corporations in the West also paid careful attention to the management of human resources.2

Before these developments, the term ‘personnel management’ was widely used to describe the process of managing people at work. Personnel management was not perceived as having strategic significance, nor indeed as a special concern of line management. Rather, it was seen as a necessary function. The primary concern of the personnel department was to cope with hiring and firing, signs of trade union militancy, organisation of training programmes, administration of wages, and the delivery of welfare programmes. The 1966 edition of Functions of a Personnel Department, published by the then Institute of Personnel Management, stated that:

the term personnel management is used in its broadest sense to describe the function of management primarily concerned with what is commonly called the human factor. The personnel department is a division within the management structure where men and women are employed to help to evolve and to help in carrying out various policies of a company in matters affecting its employees.3

Today the management of human resources is generally accepted to be a primary responsibility of all managers, line or staff, facilitated and supported by a lean and competent human resource department. The thinking that has helped to bring about this change can be traced back to that doyen of management writers, Peter Drucker. In his classic text The Practice of Management, written over 40 years ago, he charged management with three functions: economic performance, managing managers, and managing workers and work. ‘Man alone of all the resources available to man’, he said, ‘can grow and develop’, and then added, ‘It implies the consideration of human beings as a resource …’.4

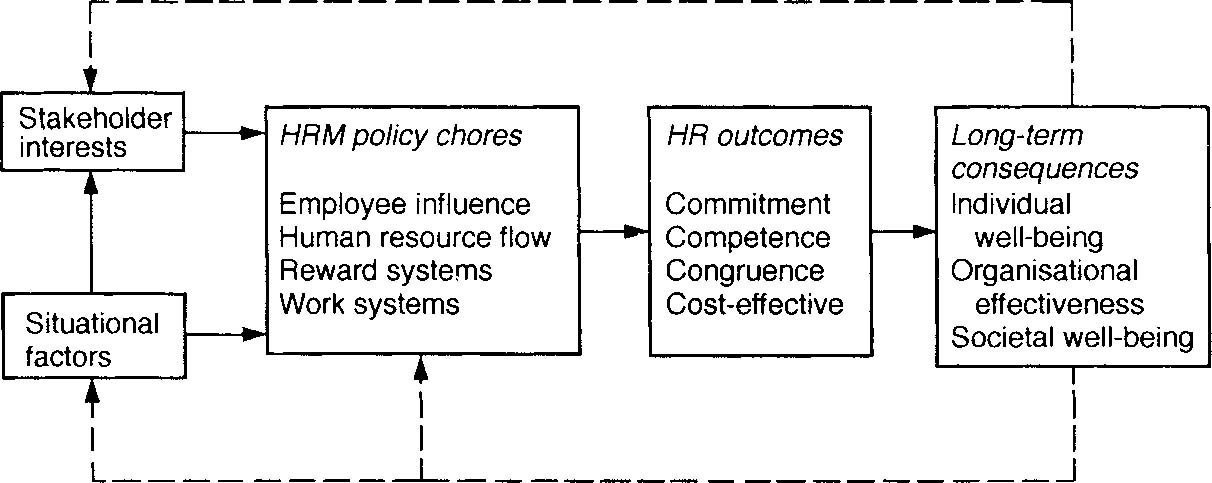

A significant and more recent contribution towards understanding human resource management (HRM) has been made by the Harvard Business School, who in 1980 introduced a human resource management syllabus onto their MBA programme. A research colloquium organised by Harvard in 1984 bringing together leading academics and business men considered the future character of HRM, which led to the analytical framework illustrated in Figure 0.1.

Figure 0.1 Harvard framework for human resource management

The concepts contained in Figure 0.1, such as ‘stakeholder interests’, ‘situational factors’, and ‘HR outcomes of commitment, competence, congruence and cost effectiveness’, are still in the process of being worked through by contemporary organisations.5

In further developing this line of thinking in the USA, Walton has contrasted old and new assumptions and approaches to the management of human resources, underlying the radical move from old-fashioned ‘control-based’ policies to new ‘commitment-based’ policies and systems.6 This is illustrated in Table 0.1.

Table 0.1 Contrast between control-based and commitment-based HRM systems

Source: Walton, Towards a strategy

These new philosophies and policies on managing human resources have been more readily accepted by senior practising managers in the UK than by academics. Senior managers have had to respond to a shift to a global market and greater international competition, and the consequent need for a better educated and trained workforce, total quality practices, and lean decentralised organisation structures. Academics strongly influenced by the legacy of an industrial relations philosophy which emphasised conflict and espoused a pluralistic view of the workforce have had difficulty in coming to terms with a new scenario based on a unitary frame of reference.7,8 Fortunately such introspection has now largely given way to studies of these new organisational developments, leading to the development of a recent literature which recognises the significance of new-style HR policies, and helps our understanding of the circumstances in which they may or may not succeed.9,10,11

The chapters in this book successively outline recent thinking on human resource policies and practices, applying a critical approach. The authors aim to provide a good understanding and a sound knowledge base that will contribute to greater competence at work. Reference is made to the respective roles of line managers and human resource specialists as appropriate, but there is an assumption throughout that responsibility is shared for the effective management of human resources.

References

1. Pascale R, Athos A. The art of Japanese management. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

2. Peters T, Waterman R. In search of excellence. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

3. Moxon G. Functions of a personnel department. London: Institute of Personnel Management, 1966: 3.

4. Drucker P. The practice of management. London: Heinemann, 1961.

5. Lundy O, Cowling A. Strategic human resource management. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.

6. Walton RE. Towards a strategy of eliciting employee commitment based on policies of mutuality. In: Walton RE and Lawrence PR eds. HRM trends and challenges. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1985.

7. Keenoy T. Human resource management: rhetoric, reality, and contradiction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1990; 1(3): 363–384.

8. Storey J. Introduction: from personnel management to human resource management. In: Storey J ed. New perspectives on human resource management. London and New York: Routledge, 1989.

9. Guest D. Personnel management: the end of orthodoxy? British Journal of Industrial Relations 1991; 29(2): 149–175.

10. Storey J. The take-up of human resource management by mainstream companies: key lessons from research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1993; 4(3): September: 529–553.

11. Schuler R. Strategic human resource management: linking the people with the strategic needs of the business. Organisational Dynamics 1992; Summer: 18–31.