1 Developing a strategy for human resources

One issue dominates the subconscious thinking of both individuals and organisations — survival. And for organisations to survive in today’s environment they must be successful. Survival and success dominate the thinking of chief executives, top management, and strategic planners. ‘Strategy’ is a concept borrowed from the military, where it denotes the art of war, and hence military survival. In business it denotes the art of economic survival.

When developing their strategies, companies in the private sector normally place their emphasis on financial, marketing, and operational considerations. In the public sector strategies have additionally had to take account of political matters. Until recently it was rarely thought necessary to consider human resource when strategies were developed. While the need for a productive and cooperative workforce was generally acknowledged, it was assumed that this could be comfortably achieved subsequent to the development of corporate strategy.

As indicated in the introduction to this book, the strategic significance of human resources has been increasingly recognised by Western corporations over the last decade. Factors that have contributed to this recognition have included the manifest success of Japanese industry that has paid great attention to people, their values and their skills, technological change which has increased the need for a well-educated and highly skilled workforce, and the positive example provided by a number of world-class Western organisations that have a coherent strategy for human resources.

1.1 The nature of corporate strategy

Faulkner and Johnson see corporate strategy as being concerned with the long-term direction and scope of an organisation.1 It is crucially concerned with how an organisation positions itself in its environment and in relation to its competitors. By taking a long-term perspective in preference to a short-term tactical manoeuvre, competitive advantage is promoted.

The application of strategy to the public sector and ‘not for profit’ organisations maintains this long-term perspective, but has to be framed in different terms: the emphasis is not on achieving competitive advantage but on providing a public service of appropriate quality within budgeted cost restraints (although the distinction between public and private organisations has been blurred in recent years by government pressures for ‘internal markets’ and competitive tendering). The Local Government Board recommended in their 1991 report that ‘Authorities adopt a strategic approach … traditional structures, practices and procedures are being re-examined to find new ways of improving service to their communities.’2

The best manner in which to formulate and execute strategy has been the subject of considerable debate. Whittington found 37 books in print bearing the title Strategic Management3. Until recently a rational planned approach has been the norm, with an emphasis on ‘aims’ and ‘missions’, and a systematic evaluation of alternative ways of achieving these. This has then been followed by selection and statement of the best way forward, and detailed plans extending several years into the future. Once approved by the chief executive these plans are ‘cascaded’ down through the organisation in hierarchical fashion.

In what has become a classic definition, Chandler in 1962 defined strategy as ‘the determination of the long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources of action and the allocation of the resources necessary to carry out these goals’.4 Popular approaches in the 1970s and 1980s placed emphasis on an appraisal of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (as typified by SWOT analysis and the Boston Consulting Group’s portfolio) as an aid to determining strategy. Both approaches appealed to top management in Western organisations, convinced that they held a monopoly of intelligence and wisdom.

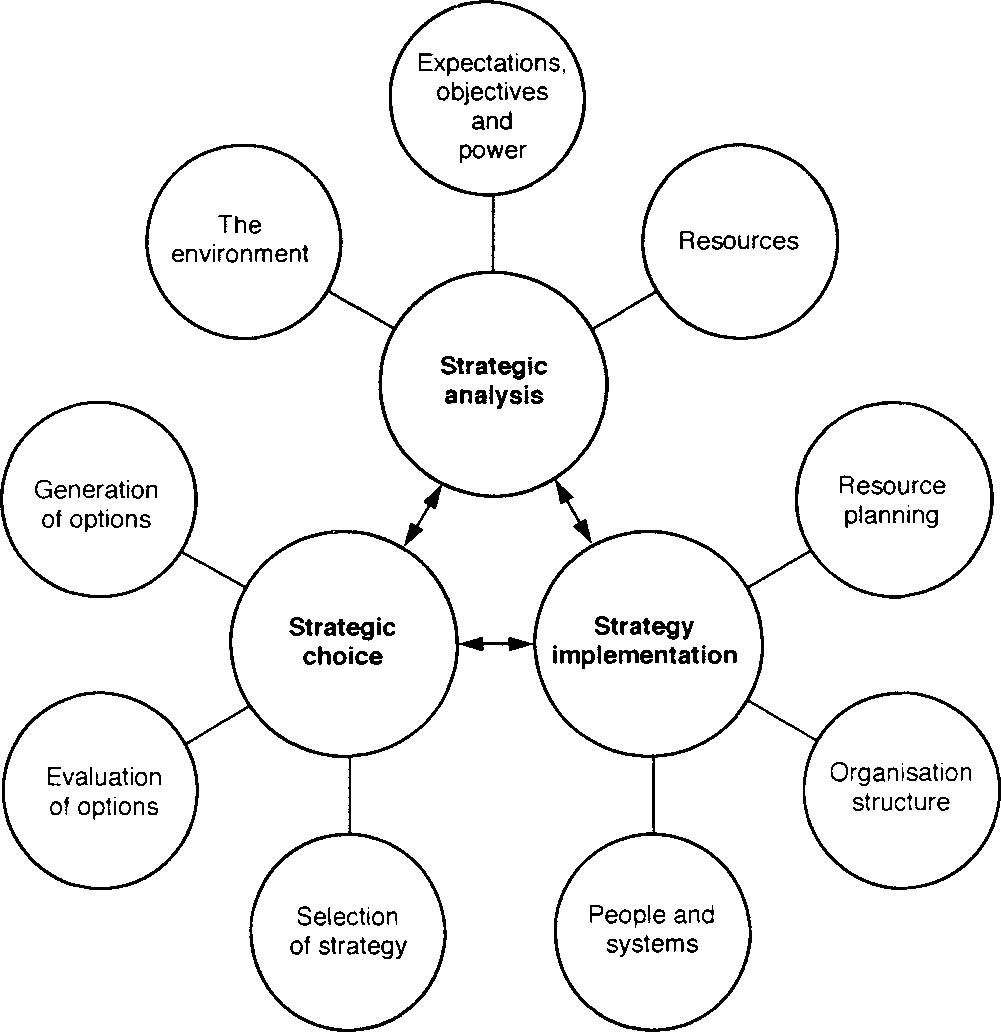

Research has challenged both the validity and practicality of this approach.5,6 All too frequently, decision-making in boardrooms has been found to reflect power structures and group dynamics rather than rational analysis. The ability to predict events several years into the future has also been questioned, given the rapidity of change in the contemporary business environment. In consequence, authorities such as Mintzberg advocate an incremental approach which treats strategy formulation and implementation as a ‘craft’, and he comments that ‘formulation and implementation merge into a fluid process of learning through which creative strategies emerge’. In his view, effective strategies combine deliberation and control with flexibility and organisational learning. Ansoff, however, considers this ‘emergent’ approach as unsuited to a turbulent environment, as strategies are produced that are out of date before they can be implemented.7 Johnson and Scholes8 see corporate strategy as ‘the matching of the activities of the organisation’s activities to its resource capability’, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The elements of strategic management

Source: Johnson, Scholes, Exploring corporate strategy

1.2 Corporate strategy and human resource strategy

A human resource strategy can likewise be developed as a matching process, concerned with the manner and extent to which the stock of manpower should be varied to match predicted changes in the environment, and integrated continuously into corporate plans.

The model in Figure 1.1 highlights five areas where the analysis and planning of human resources are significant in the strategic management process, namely, ‘environment’, ‘organisation structure’, ‘people and systems’, ‘resources’, and ‘resource planning’. The relevant aspect of the environment in this context is the labour market, which determines the supply of labour and impact on wage costs and employee attitudes. A good organisation structure is a strategic imperative, because without it the organisation will lack synergy. The right people and systems will deliver high productivity and quality, building on the human resources put in place by careful human resource planning. These factors will be considered in some detail later in this book.

While conventional wisdom now supports the integration of human resource strategy and corporate strategy, the evidence unfortunately is that only limited progress has so far been achieved. In a study of European companies Chris Brewster found the highest degree of integration among firms in Sweden, Norway, and France, and the lowest degree of integration in Germany and Italy.9 The UK lagged behind Switzerland, Spain, Finland and the Netherlands in this respect. In a study in the USA, Paul Butler found variable degrees of integration in a sample of large corporations, and commented that

In companies with two-way linkage, top management and corporate planners recognise that business plans affect — and are affected by — human resources … in these firms, consequently line managers, business planners, and human resources staff members relate to one another as strategic partners.10

Corporate strategy can also be envisaged as taking place at lower levels in the organisation. John Purcell has identified three levels of strategic decision-making.11 At the top of the organisation ‘first-order’ strategies consist of decisions on long-term goals and the scope of activities, ‘second-order’ strategies lead to decisions on the way the enterprise is structured to achieve its goals, and human resource management decisions are included in ‘third-order’ strategies tied to annual budgets, where mechanisms for making things happen are put into place. Research by Shaun Tyson using this taxonomy and based on a sample of 30 large British companies found ‘strong’ evidence that divisional management creates detailed strategies, and in many cases the role of main boards was to coordinate and shape these strategies in support of the published vision and values.12 HR directors were found to play an important role at divisional level, even though main boards frequently did not include an HR director, and Tyson concludes that HR divisional directors play an important role in the development of second- and third-order strategies. It is interesting to compare this apparent subordination of HR strategy to second- or third-level decision-making with the Japanese approach as expounded by Kenichi Ohmea that ‘The Japanese company starts with people, trusting their capabilities and potential.’13

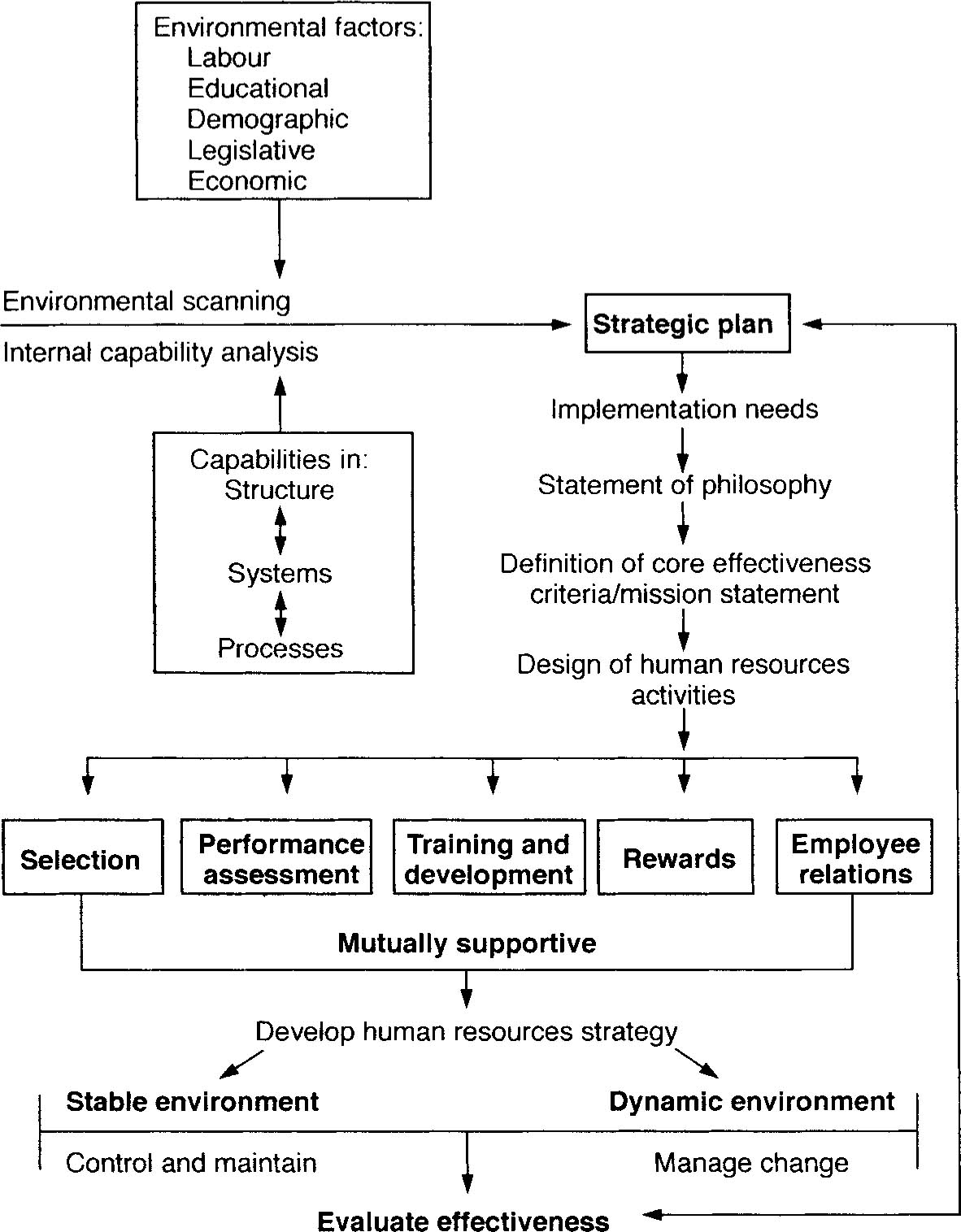

A comprehensive model of strategic human resource management has been developed by Olive Lundy, as illustrated in Figure 1.2.14

This model indicates progressive stages in developing a human resource strategy that is integrated with corporate strategy, and subsequently finds expression in third-order strategies, processes, and actions in key HRM areas such as selection, performance assessment, training and development, rewards and employee relations.

Figure 1.2 Strategic human resource management: a comprehensive model

Source: Lundy, Cowling, Strategic Human Resource Management

1.3 Structure and strategy

Designing and revising the structure of an organisation are key aspects of first-order strategy. Decisions on structure are normally taken at the highest level, usually by the chief executive advised by the board of directors. Advice is frequently taken from management consultants, but rarely from the human resource department, principally because the HR department is perceived by most chief executives as lacking the necessary expertise and influence in this area.

Creating the right kind of organisation and ensuring that it is properly staffed requires considerable planning. Organisations cannot be changed overnight, and it is important to get the structure right. ‘Structure follows strategy’ has been a much quoted maxim of corporate planners in the past. The first priority has therefore usually been to decide on a strategy encompassing markets, products, services and finance, leaving structure to later on, on the grounds that it can be designed subsequently in furtherance of the desired strategy. However, thinking is changing on this order of priorities and structure is now becoming a primary concern. Asked to state his order of priorities on this issue Tom Peters assigned top weighting to structure, followed by systems and people.15 Strategy, he argues, should then be set subsequently at strategic business unit level. ‘Top management’, he adds, ‘should be creative of a general business mission.’

To decide on the most appropriate structure, a number of basic questions have to be answered, including the following:

• How centralised or decentralised should we be in our operations and decision-making?

• How many layers do we really need?

• How formal or informal should our manner of operations be?

• Should staff report to only one supervisor?

• What should be the spans of control?

• Should staff be grouped by specialism, or in project or process teams?

• Can business processes be re-engineered, creating new and better ways of working together?

A range of options is available once these questions have been answered.

Option 1 Traditional hierarchical structures

Traditional hierarchical structures are based on theories developed in the first quarter of this century in accordance with so-called ‘scientific management’ principles. These principles have influenced the design of most medium to large-scale organisations for the first 60 years of this century.

• Decision-making is located at the top of the organisation.

• All staff report to only one superior.

• Spans of control are limited where possible to less than 10 people.

• Commands and official information must be transmitted through ‘proper’ channels of information, from the top to the bottom of the organisation.

• Staff are grouped by specialism into departments and sections.

• Authority derives from status in the organisation’s hierarchy.

• Jobs are precisely defined in written job descriptions.

• The so-called line departments are those which directly generate revenue (e.g. sales and production), whereas the so-called ‘staff’ departments provide a support and advisory service to the line departments (e.g. human resources and accounts).

This model assumes that employees at work are dominated by their individual interests and not by group considerations, and the primary source of their motivation is money. Because it treats the organisation as if it were a machine it is frequently termed ‘mechanistic’.

A version of this option is a ‘bureaucratic’ structure, widespread in the past in public sector organisations. To the above principles it adds a degree of impersonality whereby staff are selected by a central unit, possess security of tenure, and are expected to work strictly within the limits of their job descriptions. The advantages of this type of structure are stability, conformity and control; the disadvantages are inflexibility, inability to change, poor communications, and lack of cooperation between departments and different levels in the organisation.

Option 2 ‘Organic’ structures

An ‘organic’ structure is in many ways the opposite of a ‘mechanistic’ structure, and has influenced thinking on the design of organisations for the last 30 years as the limitations of the traditional model were exposed.16

• Decision-making is delegated to those with relevant knowledge, irrespective of formal status.

• Staff do not have precise job descriptions, and adapt their duties to the needs of the situation.

• Information is informal, and all channels of information are used.

• There is high interaction and collaboration between staff, irrespective of status or department.

• There is an emphasis on flexibility, cooperation, and informality.

Because of its inherent flexibility, it is not possible to capture an organic structure in an organisation chart or simple diagram. The possible advantages of this type of organisation are flexibility, capacity for change, good communications and concerted team effort. The possible disadvantages are lack of structure and inability to mass-produce articles requiring repetitive and boring work routines.

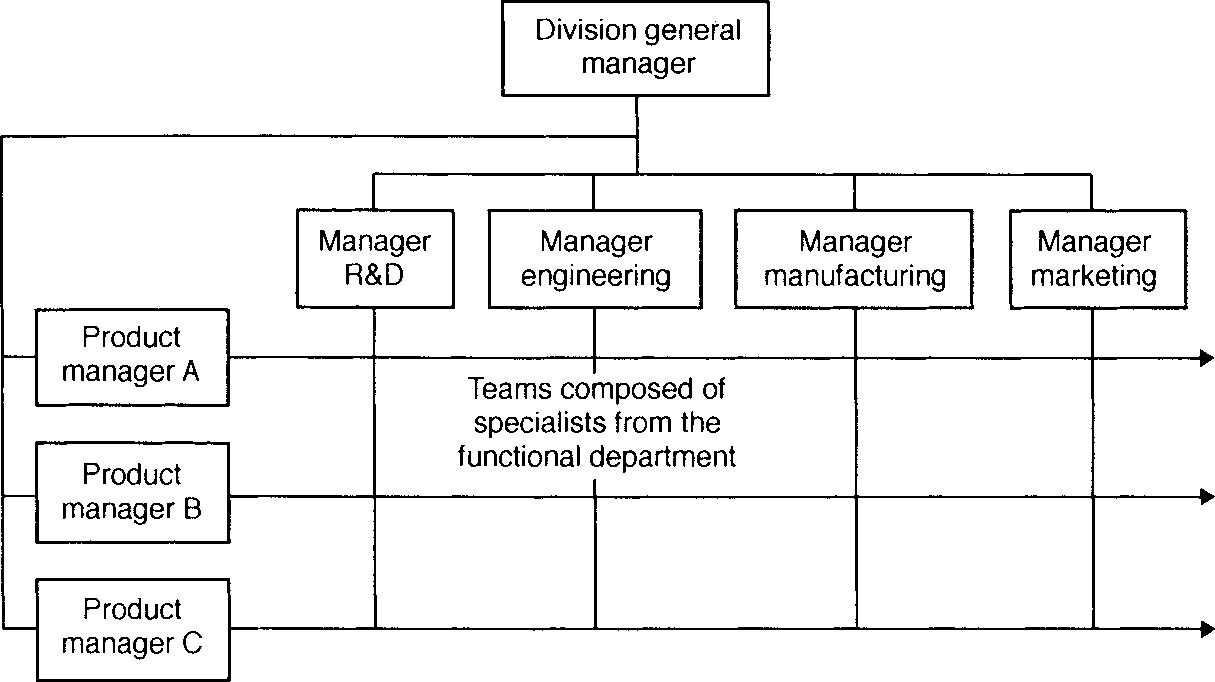

Option 3 Matrix structures

Matrix structures are an attempt to overcome the rigidities imposed on organisations by an exclusive allegiance to one department and ‘one boss’. Individual members of staff are allocated to a specialist department, representing their ‘home’ base, but spend most of their time working in mixed teams with staff from other specialist departments on projects, under the day-to-day control of one or more project leaders. There can be further dimensions to a matrix, as when staff also report to a geographically located head office, as in a multinational organisation. A matrix ‘project’ structure is depicted diagrammatically in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 A simple matrix organisation structure

The advantages are good team working, good communications, and a focus on the tasks to be accomplished. The disadvantages are possible confusion created by different reporting relationships, lack of job security when projects are completed, and lack of career development as specialisation gives way to team working.17

Option 4 Process-based structures

Chiefly under the recent impact of process re-engineering projects (sometimes termed ‘business process re-engineering’, or BPR), organisations have formed work teams around the basic processes essential to their business. This can then lead to a radical redesign of the organisation.18

An example of the redesign of an individual process is provided in the provision of mortgages. In a bank or building society the ‘process’ of providing a mortgage can be carefully mapped out from start to finish, leading to the elimination of stages that slow down the execution of the process and of any unecessary paperwork. Applied throughout an organisation, this can lead to a totally new structure, as is illustrated in Figure 1.4, based on work undertaken in the former National and Provincial Building Society.

Figure 1.4 Process-based organisation structure (based on National and Provincial Building Society)

This is sometimes termed a ‘horizontal’ organisation, for as Figure 1.4 illustrates, the result is a replacement of the traditional hierarchical structure by one based on work flows. Transition to this type of structure can be painful because it requires a radical change in the manner in which people work together, but it can result in a leaner and more effective organisation, provided the process is well managed, particularly the human resource aspects.19

1.4 Variations on the basic models

Each model is capable of being varied to some degree by different measures. Let us consider some of these.

Divisionalisation

An organisation can be split up into divisions. Divisions can be based either on geography, e.g. a ‘Midlands’ or ‘Northern’ division, or by product and market, e.g. a ‘Chemicals’ or ‘Petroleum’ division. Divisions are coordinated from a central headquarters.

The possible advantages of divisionalisation are that staff are closer to their customers and centralised bureaucracy can be reduced, allowing staff to work better together for a common purpose. The possible disadvantages are loosening of control and a weakening of identification with the present organisation.

Decentralisation

Decision-making is delegated as far down the organisation as possible. This enables decisions to be made by those with relevant technical expertise, and who are closer to customers. One version of decentralisation in the private sector is the creation of strategic business units, or ‘SBUs’.

The possible advantages of decentralisation are that decisions are made at the point of operation and delivery, and the possible disadvantages are that the centre may lose control and there may occur a degree of anarchy.

Delayering

The number of levels between top management and the shop floor are drastically reduced, frequently with a target of less than five layers. Possible advantages include improved communications, cutting out of bureaucratic layers that slow down decision-making, cost savings, and better relationships between management and workers. Possible disadvantages include negative impact on career prospects as promotion prospects are restricted, and stress created by enlarged job boundaries.

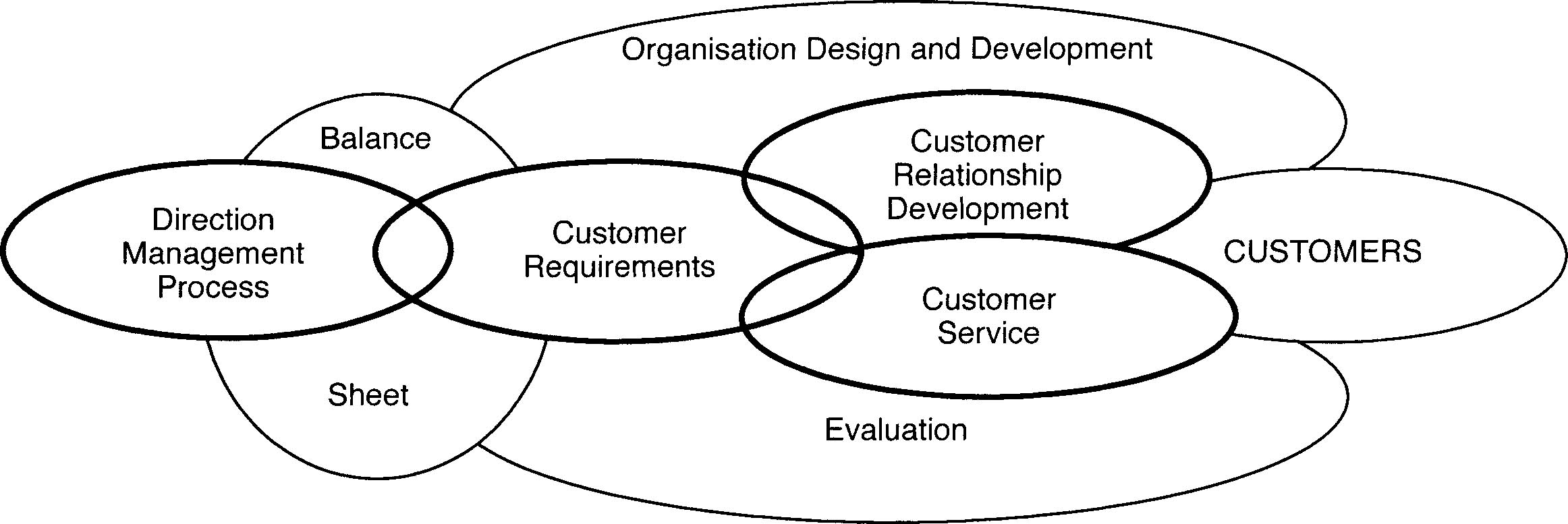

Inverting structures and including customers

In order to make the point that organisations exist to serve customers, and that head office staff exist to support the operating line management, organisation structures are now sometimes portrayed in an inverted form, as shown in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5 Inverted organisation structure, emphasising customers and values

1.5 Factors influencing the choice of organisation structure

There is no one correct model with universal applicability. Organisations must introduce the structure most relevant to achieving their corporate goals, and to the prevailing circumstances, and must be prepared to change these structures as circumstances change. Some indicators which should assist in making this choice are provided below.

Stability of the environment

The environment relevant to the organisation should be analysed in terms of factors such as markets, clients, economic and financial circumstances, technology, legal constraints, power and politics. Stability in the environment indicates a stable formalised organisation structure; change in the environment indicates a more flexible decentralised form of structure. Today most organisations are facing change and require flexible structures.

Size

Sheer size has frequently in the past led to centralisation and bureaucracy. Because bureaucracy mitigates against successful change, many organisations now aim to decentralise into smaller accountable operating units and divisions.

Culture

Cultures are difficult to change, although change may be essential. The prevailing culture (i.e. norms and values attached to work) and the practical problems of changing it must be taken into account when planning change to structures. Culture is examined in more detail in the next section.

Internal labour market

The complexity and nature of work and the levels of education and professionalism of the workforce are important. A highly qualified professional workforce can by and large be left to get on with things; indeed, full professionals expect a high degree of autonomy, and prefer to work within a looser organisation structure. However, clear objectives and effective leadership are still necessary.

Technology of operations

Technology is changing fast, and a case in point is information technology, which can facilitate decision-making. An example of this is electronic point of sale (EPOS) in stores and supermarkets. Information on precisely what is being purchased is immediately transmitted to warehouses and head office, permitting centralisation of purchasing decisions.

Power

The five factors already discussed are rational factors. Power is not a rational factor, but is so important it must be mentioned. Internal power and politics, with individuals or groups attempting to gain or maintain control of an organisation, mean that structures are designed which reinforce the position of the most powerful group or groups. However, should this conflict too much with the rational needs of the organisation to survive and change in a dynamic environment, the power elite may lose their jobs.

1.6 Culture

Culture is now treated as a first-order strategy in many large organisations, and clearly involves human resources. ‘Culture’ became something of a buzz word during the 1980s in management circles, when it became fashionable to talk about changing an organisation’s culture. The primary cause of the interest in culture was the success of Japanese manufacturers, and the assumption that their superiority was in part due to a supportive national and corporate culture. The book which more than any other publication helped to foster this interest in corporate culture was In Search of Excellence, by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman.20 Based on a study of so-called ‘excellent’ American corporations, Peters and Waterman concluded that the key to excellence lay in achieving a state of shared values among all employees in an organisation. They also concluded that Western management had been placing far too much emphasis on what were perceived as the ‘hard’ factors of strategic decision-making, namely, structure, systems, and strategy. Excellent American (and Japanese) firms, however, placed equal emphasis on the ‘soft’ factors of staff, style and skills, with a special emphasis on shared values. This is illustrated in Figure 1.6 describing McKinsey’s 7S model adapted and used by Peters and Waterman.

Figure 1.6 McKinsey’s 7S framework

A number of the American companies portrayed as ‘excellent’ in 1982 could no longer be deemed to be excellent a few years later. For example, Walt Disney went through a period of producing unsuccessful films, Caterpillar lost a major share of its market for heavy plant machinery, Atari, well known for its computer games, suffered severe losses, and the jury is still out in the case of IBM. However, these failures did not diminish the interest in corporate culture as a key to achieving success.

As well as placing an emphasis on shared values, Peters and Waterman promulgated a number of ‘rules of thumb’ for achieving excellence, many of which have passed into the vocabulary of managers everywhere. These include:

• a bias for action;

• close to the customer;

• autonomy and entrepreneurship;

• productivity through people;

• hands on, value-driven;

• stick to the knitting;

• simple form, lean staff;

• simultaneous loose-tight properties.

While these can be deemed to be simple ‘motherhoods’, they do underline certain home truths, for example, that productivity can only come through people. Whether these home truths have been fully understood and applied by top management in the UK is another matter. Only a handful of British companies reach international standards of excellence and quality.

A major criticism of the Peters and Waterman approach is that it fosters a continuation of the ‘one best way’ of managing philosophy perpetrated by scientific management writers in the first half of this century.21 All the evidence from major studies of the connection between ways of organising and management, from Joan Woodward’s classic study in the 1960s until the present day, show clearly that what may be the right approach for one organisation may be the wrong approach for another.22

Two well-known definitions of organisation culture illustrate alternative approaches relevant to strategy formulation:

Corporate culture is the pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration.

(Schein)23

The way we do things around here.

(Marvin Bower, managing director of a firm of management consultants (quoted by Deal and Kennedy))24

So management may attempt to change ‘the way things are done around here’ by direct intervention, orders, rewards, and personal example. Or they may attempt to alter patterns of basic assumptions by, for example, informing, educating, and advising.

Roger Harrison25 described four types of prevailing organisation culture:

1. role culture;

2. power culture;

3. achievement culture;

4. support culture.

A role culture emphasises order, stability and control, and is based on a quest for security. Typical of a role-culture might be an old-fashioned public sector bureaucracy. A power culture emphasises strength, decisiveness, and determination, and is based on a quest for control. Power cultures are found in some large private sector organisations where a handful of senior executives exert a large amount of power in an autocratic manner, and in privately owned smaller organisations where the controlling family may wield considerable power. Achievement cultures emphasise success, growth and distinction, and are based on self-expression. They may be found in some modern progressive organisations that encourage autonomy and self-expression. Support cultures are based on mutual service, integration and values, and are based on a sense of community. Charles Handy adapted this approach to come up with four types of organisation culture which correspond to conceptual ‘maps’ of organisation structures.26 These are Power Cultures, Role Cultures (similar to Harrison’s categories), Task Cultures and Person Cultures. Task Cultures place emphasis on the successful achievement of tasks and Person Cultures refer to organisations designed to create space for individuals to operate in and be creative.

Both these approaches link the predominating value system or culture to the design of the organisation, suggesting a match between structure and culture. This provides a useful reminder that if an organisation makes major changes to its structure it will need to promote a new and more congruent culture, and vice versa.

1.7 Human resource planning

First-order strategy is implemented through second- and third-order strategies. Third-order strategies in the HR area then find expression in human resource planning. It is frequently said of the Japanese that their success comes about through careful planning.27 When the Nissan plant in the North East of England decided to build the new Micra model, they took on new employees up to nine months before production got under way in order to ensure that adequate training and team developments had taken place. This followed very careful selection of new employees.

This process has traditionally been referred to as manpower planning, but is now generally termed human resource planning. It aims to provide answers to questions such as:

• How many employees will we need next year?

• What skills and competencies will we need?

• What employee relations will we need?

• What is our current stock of human resources and skills?

• At what rates do we lose staff because of turnover?

• What sort of age structure do we have, and do we want?

• Should we train our staff, or buy them in?

The penalties for not carrying out human resource planning can be costly. Heavy costs can arise from not having staff ready and trained to operate new equipment and machinery, having to buy in staff at short notice, hire temporary staff, being faced with the consequences of a spate of unanticipated retirements, and probably most important of all, being unable to deliver a quality service to customers.

The simplest way of tackling human resource planning is by thinking of it in terms of demand and supply. Demand can be forecast from corporate plans. Supply can be forecast by working out the stock of manpower currently employed, calculating the likely shortfalls and surpluses, and planning accordingly.

Forecasting the likely demand for human resources should be a cooperative exercise between the corporate planners, line managers, and the HR department. Departmental heads should estimate their staffing needs and staffing budgets, a process which normally takes place at least once a year in medium and large organisations. Corporate planners then look at these estimates across the board and propose modifications to take account of forecast changes in markets and technology. At this stage the HR function can make an input in terms of proposed organisation change programmes and on the basis of information held on staffing needs.

Demand forecasting can normally be carried out with some degree of precision up to a year ahead, in other words, for as long ahead as markets and services to clients can be accurately forecast. However, longer-term forecasts of two to five years are also needed in order to plan expansion, recruitment, and ‘downsizing’ programmes and the appropriate training programmes for apprentices, graduates, and multi-skilling initiatives. These longer-term forecasts can be revised every year on a ‘rolling’ basis.

The supply side of human resource planning starts by ensuring accurate and up-to-date information is available on the current labour force. This requires good personnel records which provide easily retrievable data on human resources. Organisations employing more than 50 staff should as a rule use computerised personnel information systems (CPIS) to facilitate data retrieval and analysis.

1.8 Human resource information

Data on individual employees should include all the obvious information required for day-to-day purposes such as grade or status, address, sex, date of birth, insurance number, payroll number, next of kin, marital status, employment record, educational qualifications, ethnic origin, disabilities and fluency in foreign languages.

Keeping records accurately and up-to-date is essential. Employees are notoriously lax in notifying changes in their personal situation. One way of counteracting this is to supply individual employees with a print-out of their personal information at least once a year so that they can check and correct it if necessary.

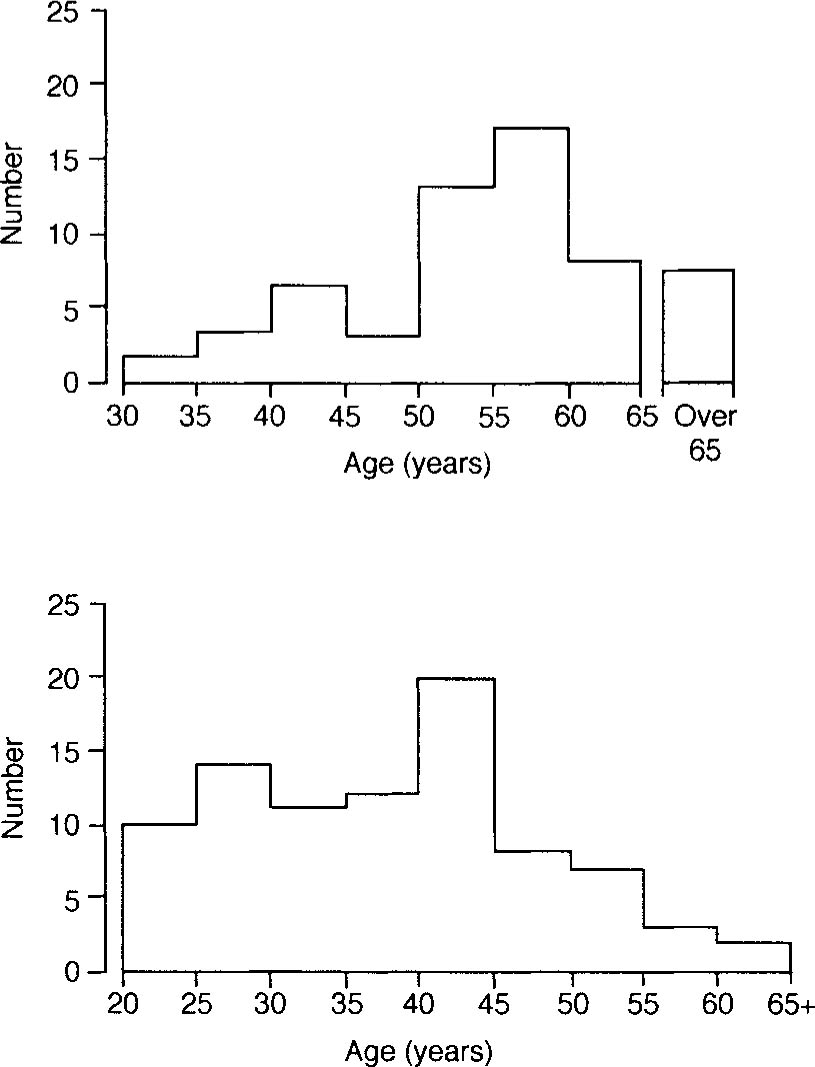

Computerised personnel information systems facilitate the analysis of trends and the presentation of ‘snapshots’ or profiles of sections of the workforce. An example is provided by age profiles. These indicate whether an organisation, a department, or a group of employees sharing a common skill are ‘top heavy’ with a high proportion of staff rapidly approaching retirement age, ‘bottom heavy’ with a high proportion of young and less experienced staff, or well balanced in their age distribution. Examples are shown in Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.7 Two age profiles demonstrating a lack of balance and a need for planning

It may of course be advantageous to have a top heavy group of employees if ‘downsizing’ is being planned, because they can be offered early retirement coupled with an early pension (in accordance with current income tax regulations). A bottom heavy profile may or may not be advantageous, depending on current circumstances; younger employees may be more energetic, but less experienced and more prone to leave.

Forecasts of labour wastage and absenteeism also need to be taken into account at this stage. Both these issues are examined in detail in the next chapter, in the context of recruitment and retention.

1.9 Putting the plan together

An examination of supply forecasts in the light of demand forecasts will indicate the areas where special initiatives are required to achieve balance. It is normal to draw up plans for action under a conventional list of functional headings, for example:

• Recruitment and selection: in which key areas should recruitment take place over the next twelve months?

• Training: what are the training and development priorities, and how should they be phased?

• Redundancies: where are redundancies likely to occur, and how should we set about consulting interested parties and arranging our placement or retraining activities?

• Employee relations: how should we maintain good relations with various worker representative groups and improve consultation and communication?

• Motivation: what new reward management initiatives and other measures to improve motivation are called for?

• Productivity and flexibility: what measures to improve productivity and flexibility, such as team working, are called for?

• Performance management: how can performance be managed better? Do appraisal schemes require review?

• Management development: what management development programmes are needed to develop appropriate competencies in managers in pursuit of new performance targets?

Clearly, there is overlap between these areas, but that is the way it should be. Human resource plans must be integrated into a concerted drive by line and HR managers to achieve organisational goals.

1.10 References

1. Faulkner D, Johnson G. The challenge of strategic management. London: Kogan Page, 1992.

2. Local Government Board. Strategies for success. London: HMSO, 1991.

3. Whittington R. What is strategy, and does it matter? London: Routledge, 1993.

4. Chandler AD. The history of the American industrial enterprise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962.

5. Quinn JB. Strategies for change: logical incrementalism. Homewood, II: Richard D. Irwin, 1980.

6. Mintzberg H. Crafting strategy. Harvard Business Review 1987; July-August: 66–75.

7. Ansoff HI. Critique of Henry Mintzberg’s ‘The design school — reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management’. Strategic Management Journal 1991; 12(6): 449–461.

8. Johnson G, Scholes K. Exploring corporate strategy. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice-Hall, 1989.

9. Brewster C, Larsen HH. Human resource management in Europe: evidence from ten countries. International Journal of Human Resource Management 1993; 3(3): 409–434.

10. Butler PF. HR and strategic planning in eight top firms. Organizational Dynamics 1995: Summer.

11. Purcell J. The impact of corporate strategy on human resource management. In: Storey J ed. New perspectives on human resource management. London: Routledge, 1989.

12. Tyson S. Human resource strategy. London: Pitman, 1995.

13. Ohmae K. The mind of the strategist. London: Penguin, 1983: 224.

14. Lundy O, Cowling A. Strategic human resource management. London: Routledge, 1996.

15. Peters T. Liberation management. London: Macmillan, 1992.

16. Burns R, Stalker GM. The management of innovation. Welwyn Garden City: Tavistock Publications, 1961.

17. Bartlett CA, Ghoshal S. Matrix management: not a structure, a frame of mind. Harvard Business Review 1990; July-August: 138–145.

18. Hammer M, Champy J. Re-engineering the corporation. London: Brealey, 1994.

19. O’Brien R, Wainwright J. Winning as a team of teams — transforming the mindset of the organisation at National and Provincial Building Society. Business Change and Re-engineering 1993; 1(3), Winter: 19–25.

20. Peters T, Waterman RH. In search of excellence. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

21. Wilson D, Rosenfeld R. Managing organisations. London: McGraw-Hill, 1990.

22. Woodward J. Industrial organisation: theory and practice. London: Oxford University Press, 1965.

23. Schein E. Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1985.

24. Deal TE, Kennedy A. Corporate culture: the rites and rituals of corporate life. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1982.

25. Harrison R. How to describe your organization. Harvard Business Review 1972; Sept.-Oct. 119–128.

26. Handy C. Understanding organisations. Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1993.

27. Wickens P. The Road to Nissan. London: Macmillan, 1987.