How to focus on your first goals

In the previous chapter you found out that the secret of getting massive results is to work out the 20% of your work or your leisure time that gives you the greatest benefit, and to spend more time doing that, and less time doing the 80% of things that give you less value. Once you know what that vital 20% is, you can set goals that will speed you towards success. But if you’ve tried setting goals in the past you may find this a discouraging prospect because you don’t yet know the two fatal flaws in most goal-setting approaches. In this chapter, you’re about to find out not only what these flaws are, but also how to overcome them.

How to set SMART goals

Focusing requires being specific about what you want to achieve, which is where SMART goals come in. First, let’s look at the process of setting goals, so then you can apply it to the areas you identified in the last chapter.

What are SMART goals? S stands for specific. Goals like “lose some weight” or “make more money” or “be more popular” aren’t very useful because they are so vague; if you lose one ounce, you’ve lost weight but aren’t likely to be satisfied, so it makes sense to set a specific weight target. The same applies to money and even to a personal quality like being more popular. What, exactly, would being more popular look like? Does it mean having two more close friends? Or having another half a dozen casual friends? If you have trouble coming up with specifics, just ask yourself, what will you see and hear when the goal has been reached, which is different from what you see and hear now?

When you make these decisions be sure that you are using criteria that are meaningful to you, not ones you think other people expect from you. Trying to fulfil someone else’s expectations is a fool’s errand, not least because if we do happen to fulfil them, they can be changed in an instant to something else that will keep us struggling.

It’s also better to be positive – so rather than having the goal of “losing 10 pounds”, it would be better to “achieve a healthy weight of X”. Otherwise you will constantly have your mind on the negative.

M stands for measurable. Once you have been specific, the way to measure whether or not you have reached the goal usually is implied. If it’s about weight, you’ll use the scales or a bodyfat monitor; if it’s about money, your bank balance will tell the tale. In fact, whether or not you can measure a goal is a good test of whether you have been specific enough. If not, go back and adjust the goal.

The next two goals, A and R, are for attainable and realistic. I’m not a big fan of emphasising these too much. Goals need to be ambitious and glorious if they’re going to motivate you to do the work necessary to reach them, and the most exciting goals tend to be the ones you’re not 100% sure are attainable and realistic. Can your book become a best-seller even though you’ve never written one before? Can you start a business that makes enough money within the next five years to allow you to stop working and devote yourself to your hobby or to charitable work? Well, lots of people have done those things. And there’s only one way to find out: write the book or start the business and see what happens.

The only real question is whether the sacrifices you are willing to make match the scope of the goal. If the answer is yes, go for it. If you give it your all, you’ll probably get there.

By the way, if you want to consult someone about whether to embark on your big plan, please ask someone who has done it, not someone who hasn’t. The former is an expert on how it can be done, the latter is an expert on how it can’t be done.

The T in SMART is for timely, which usually is interpreted to mean that you have to have a deadline for reaching the goal. This is the one that destroys a lot of hopes and plans.

Beware the deadly deadline

Here’s the way it usually goes: you set a goal with a deadline, something like, “I will weigh 10 stone by 1 March”, or “I will get an agent to represent my book by the end of September”, or “I will start my new internet-based business by 15 February”.

Then you do whatever you think will allow you to reach the goal by your deadline or target date. And, if you’re like most of us, quite often you fail. Either you actually gain weight, or you stay the same, or you lose some weight but don’t reach the target. Or you don’t get an agent by the end of September, and because of a problem with your website, your online business isn’t actually ready to go by mid-February.

You’ve failed, and when we fail we feel disappointed or depressed and we’re likely to give up on the goal. Furthermore, we are a bit less likely to try to reach another goal in the future.

There are two fatal weaknesses in this traditional approach to setting goals. The first is setting the deadline. The self-development gurus would be aghast at that statement. They say that a goal without a deadline is just a wish. To that I would say, often a goal with a deadline is a prescription for failure. Here’s why. When you set out to reach a goal, generally you don’t yet know how you’re going to do it. You may have some idea about the strategies you will use and the tasks you will implement, but you can’t know whether or how well it will work. The second flaw is that in many cases reaching the goal requires the cooperation of other people. You can influence their responsiveness but not control it. Therefore, how can you possibly set a time limit for success?

There is only one true goal deadline

Above, I mentioned how the process usually goes. Here is how it should go, if you really want to achieve the goal:

- You set the goal. For our example, we’ll stick with reaching a target weight.

- You do whatever you think will get you there. Let’s say that you decide to walk a mile three times a week in order to burn up calories, with the intention of losing one pound per week.

- You monitor how well the process is working. If what you’re doing gives you the results you want (for example, you find you’re a pound per week closer to your goal), you just keep doing it until you reach your goal.

- If what you’re doing isn’t giving you the results you want, you brainstorm alternatives and commit to doing something different. This may be just a small adjustment, or it may be a total change of strategy. For instance, you might find that you’re losing only a tiny amount of weight, so you decide that in addition to the extra walking, you will have only fresh fruit for snacks and dessert. Or you may decide that you will try working out with a personal trainer twice a week.

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 until you reach the goal. Your deadline becomes “whenever I have achieved what I set out to achieve”. Your commitment is just to keep on doing something different, until you find what works. With some goals you’ll get there fast, with others it will take longer. But with this approach there is no failure, only a learning process.

I want to repeat for emphasis: in this approach, there is no failure! The only way you could fail would be to give up.

This also helps you avoid the “faster and more” syndrome. That happens when a deadline approaches and the methods you are using aren’t working very well. The impulse is to try to meet the deadline by doing whatever you’re doing faster and/or doing more of it. But doing more of what doesn’t work, or doing it faster, obviously isn’t really the answer. Without the pressure of the deadline, you are more likely to be open to considering alternative strategies.

THE STUDY THAT NEVER WAS

Many self-development books include the story of a study that was done at Harvard (or sometimes they say Yale) back in the 1950s, in which students were asked whether they had written goals. Thirty years later, the 3% who said yes had earned more than the other 97% put together. The only problem is that the study never existed. No one is sure how the story got started, but there is no evidence that such a survey ever took place. However, many successful people do say they had written goals.

This doesn’t mean that you can’t set deadlines for tasks under your control within the goal. For example, if your goal is to find someone to design your website for your new internet business, you can resolve to research candidates and contact the top three by the end of the week. If your goal is to find an agent, you can write to three of them by tomorrow. If you decide to work out at a gym, you can set yourself the deadline of joining one by Monday.

Grand goals are great but break them into chunks

Grand goals pull you forward into the future you want for yourself. At the same time, it’s important to break them down into smaller chunks that allow you to have a continual feeling of progress and achievement. Don’t put off celebrating until you reach the ultimate goal. Establish milestones and celebrate those as well.

Planning is good, doing is better

The steps of the process require a little planning on your part, but beware of getting caught up in the fun of planning to the exclusion of actually taking action. If you love coming up with elaborate plans, diagrams, flow charts, mind maps, etc. (I know whereof I speak), consider cutting back on the planning and putting more attention on achieving. By all means use charts and other visual aids to help you focus on what you need to do, but make sure they are not a substitute for actually doing the tasks. In business, the two parts of the process are referred to as planning the work and working the plan.

The fact that things are changing more quickly than ever also means that we have to be more flexible. These days, having a five-year plan that we consider set in stone is not realistic. You have to be ready to pay attention to clues along the way that might point you in a better direction, either about where you’re going or how to get there.

There’s a good analogy for this in an experiment conducted in the field of art. The work of two sets of skilled art students was compared. The first set knew the outcome they wanted, planned it carefully, and moved towards it step by step, with minimal changes. The second group had only a rough idea of what they were going for, and they changed their designs an average of 17 times. At the end, judges evaluated the two sets of paintings, and found the second set to be more creative. The lesson is that leaving enough flexibility for variation and experimentation will give you better results.

Your strategy for persistence

So far, so good. But there is a second hidden obstacle that you need to overcome. Often we commit to a strategy (for example, go walking three times a week) and we do well keeping it up for the first week or even the first month. Then life gets in the way and we find that we’re going only once a week, or not at all. The outcome: failure. Every gym counts on this. In January, lots of people sign up for an annual membership (the effect of New Year’s resolutions) but by March most of the new members stop showing up. Great if you’re the gym; not so great if you’re the member!

We not only need a strategy for reaching a goal, we also need a strategy for making sure that we follow through with our own strategy. As I said above, the only way you can fail is if you stop. But often we do stop implementing the strategy. As soon as you notice that happening, you can implement Plan B:

- Decide whether you stopped because it wasn’t working after you’d given it a fair trial. If yes, then it’s time to brainstorm a new strategy and implement that one. The same is true if you stopped because whatever you were doing is too hard to implement. For example, maybe you resolved to go to the gym seven days a week, but you’re finding that this isn’t realistic. You could decide that you’ll go three days a week, and see how that works.

- If you stopped just because you forgot, or it was inconvenient, or you got lazy, then it’s time to brainstorm a strategy for how you can make it easier, more pleasant, and more likely to be on your mind. In our example, this could be by finding a workout buddy, or hiring a personal trainer, or promising to give your teenager a sum of money every time you miss your appointment at the gym.

LEARNING EXPERIENCES

By considering a temporary failure as just a step towards eventual success, you remove its stigma. If you find this difficult, take an inventory of the skills you have now, in every part of your life. Then consider how many mis-steps or learning experiences you had on the way to mastering these skills. Most likely you will have to think hard, because once we reach a goal we tend to forget the obstacles we overcame in the process. That will also be the case when you have reached the goals that may at the moment seem distant.

You can’t focus on what you don’t see

Studies have shown that you are likely to snack more when sweets are in a transparent container than in an opaque one, and when the container is within easy reach rather than when you have to get up to get to it. These results are not exactly earth-shaking, but they do remind us of an important principle: namely, out of sight, out of mind (as well as “in sight, in mind”).

If you want to be sure to spend time every day working on something that is important to you, keep a symbol of it visible or audible. This could be a photo or drawing, a word or a phrase, or a piece of music. It helps to change this symbol periodically to refresh its power to remind you to take action.

Time to focus on your top three goals

With this understanding of how goal setting really works, you’re ready to set your own top goals. Look back at your 80/20 lists, give some thought to what goals you would find most exciting and fulfilling, and then write down the three that you would most like to achieve:

Which of these are you ready to commit to, starting right now? You can choose one, two, or all three. If you can tell that doing all three would be extremely time-consuming, then start with just one or two. Succeeding at one will give you greater energy and satisfaction than struggling to achieve three at the same time. If you do want to go for more than one, it helps if they’re not all in the same sector of your life. For instance, you might choose one goal that relates to your career, one that relates to fitness and health, and one that is about improving an important relationship.

For each of the goals get a nice notebook that you will enjoy writing in. You can use the blanks and forms in this book, but you’ll also want more space to record all the actions you take, the milestones you pass, the strategies that work really well and that you can apply in the future to other goals, and so on.

Start with these questions

For the goal that you consider most important, answer the questions below (if you need more space, use your notebook). For our examples, let’s say that you realised in your 80/20 evaluation that you make the most money doing design work, but your lack of expertise in using the Photoshop software program is holding you back. One of your goals could be to acquire those skills.

- Identify what the situation is like now. Be as specific as possible.

Example: I bought Photoshop instructional DVDs but have never used them. - What did you do (or not do) that is responsible for how this situation is now?

Example: I never scheduled time to learn the program. - What will you do differently in order to get the outcome you want?

Example: I will spend four hours a week learning the program. - What do you need to have or do in order to be sure that you can actually do what you have specified in the previous step?

Example: I have to decide what I’m doing for four hours a week currently that I will replace with four hours of learning. - What resources (time, money, help from others) do you need? How will you get them? Is there anything you need to give up or stop doing in order to free these resources?

Example: The resource I need is time. I will cut back by four hours a week on watching TV. I also need to put in place a system that reminds me to do the lessons. - Do the different things and conduct an ongoing evaluation of whether they are working. If not, consider what you might do differently to get the results you want. Keep doing this until you have reached the goal.

Example: If you find yourself consistently unable to spend four focused hours at home learning the program, you might want to consider taking your laptop to a library or other place where you won’t be interrupted. Or you may find that self-instruction doesn’t work so well for you and that it would be better to do a course.

If you want to commit to more than one goal, answer the same questions for each one.

Rev up your passion with a Top Ten list

Particularly if your goal is an ambitious one, you may feel daunted by the prospect of starting to aim for it. Maybe you’re familiar with talk show host David Letterman’s Top Ten List. You can adapt it to get yourself off to a rousing start. Make up a list of the Top Ten reasons why you believe each goal is important to your future, or why you really want to achieve it. This list will help motivate you if you run out of steam along the way. It can even be useful to make up big Top Ten posters to display in your office or meeting room, to remind yourself of these key motivations. Try this now for one of your goals.

Top Ten reasons I want to achieve this goal:

BE PREPARED

If you find your motivation faltering, put your Top Ten list on a slip of paper and carry it with you in your wallet or purse and review it frequently. It may also be a useful antidote to the ease with which other people come up with reasons why your goal will be hard to reach. Most people’s default setting is negativity, so being ready to counter it will help you.

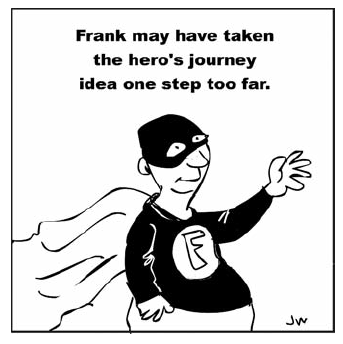

See yourself as the hero you are

Another great way to gain confidence in your ability to reach your goal is using the hero’s journey as a template for your actions. The idea of the hero’s journey stems from the work of Joseph Campbell, who was one of the world’s foremost students of mythology. He found that in many cultures there were myths that had basically the same structure: a hero going on a quest.

Along the way the hero finds a mentor, but the mentor can go along for only part of the journey, and then the hero has to proceed alone. The hero faces various tests and challenges, and goes deeply into the world of his adventure.

At some point he confronts the greatest challenge and may despair of succeeding or even surviving. At this stage, he discovers a new strength or sense of purpose, and he goes on to triumph.

Often the treasure the hero wins is symbolic – that is, something real like a gem or golden goblet that also represents some new knowledge or wisdom he has gained as a result of his journey. Sometimes this treasure benefits not only the hero but also the people around him or even his whole tribe or country.

If this pattern sounds familiar, that’s not surprising, because it is a story structure also used in many novels and films. George Lucas used it for his first three Star Wars movies and struck up a friendship with Campbell.

Even more interesting, though, is that it is a pattern that fits many of our real-life adventures. When I conduct my Create Your Future workshop, I invite participants first to use this structure to describe how they have handled a challenge in the past – for example, going to college, starting a career, or learning a new skill. Often, people are surprised to realise they’ve been heroes.

Then I ask them to use this structure to describe how they could accomplish something they haven’t done yet. The result is always interesting and sometimes profound. Not only is the hero’s journey a useful planning tool, but the effect of thinking of ourselves as heroes and heroines on a journey of adventure can have a fantastic motivational effect. Switching from “I have a problem” or even “I have a goal” to “I am on a quest” is a big shift.

Try it yourself with one of your big goals. Fill in the blanks below, and whenever you’re not sure of what the answer is, just take a guess. If you relax and let answers come to you, you may be surprised that your subconscious mind offers up more about this journey than you knew you knew.

Your heroic journey

- The hero is introduced in their ordinary world. (What are you doing now, just before you embark on your heroic journey?)

- The call to adventure. (What is the thing that made you realise that you have a problem or challenge, or that you want to start a new adventure?)

- The hero is reluctant at first, and has a fear of the unknown. (What is your greatest fear about embarking on this new adventure?)

- The hero is encouraged by the Wise Old Man or Wise Old Woman. (Who is your mentor or role model who can give you some kind of guidance or inspiration? It can be a real person from the past or present, or even a character from fiction.)

- The hero passes the first threshold and fully enters the world of the new story. (At what point will you make – or did you make – a full commitment to your adventure?)

- The hero encounters tests and helpers. (What do you think will be some of the early challenges you will face? Who can give you support and help?)

- The hero reaches the innermost cave – a dangerous place. (What do you think will be the point of greatest challenge – a time when you might ordinarily have considered giving up?)

- The hero endures the supreme ordeal, appears to die and be born again. (What quality will allow you to survive the greatest challenge? What will be the signal of your rebirth?)

- The hero seizes the sword and takes possession of the treasure. (What is the treasure you will win? It could be knowledge and experience or something more tangible.)

- The road back and the chase. (Once you have reached your goal, what smaller difficulties might still need to be overcome?)

- The hero returns with the treasure back to the ordinary world. (What will be different in your world when you have achieved the goal? How will it affect others in your circle?)

JOSEPH CAMPBELL (1904–87)

Campbell was a professor of mythology, writer and orator. His books include The Hero with a Thousand Faces and the four-volume The Masks of God, but the general public became aware of him via his series of interviews with Bill Moyers, called The Power of Myth. It was first broadcast on PBS in the USA in 1987, the year after Campbell’s death, and has been repeated many times as well as being available

on DVD.

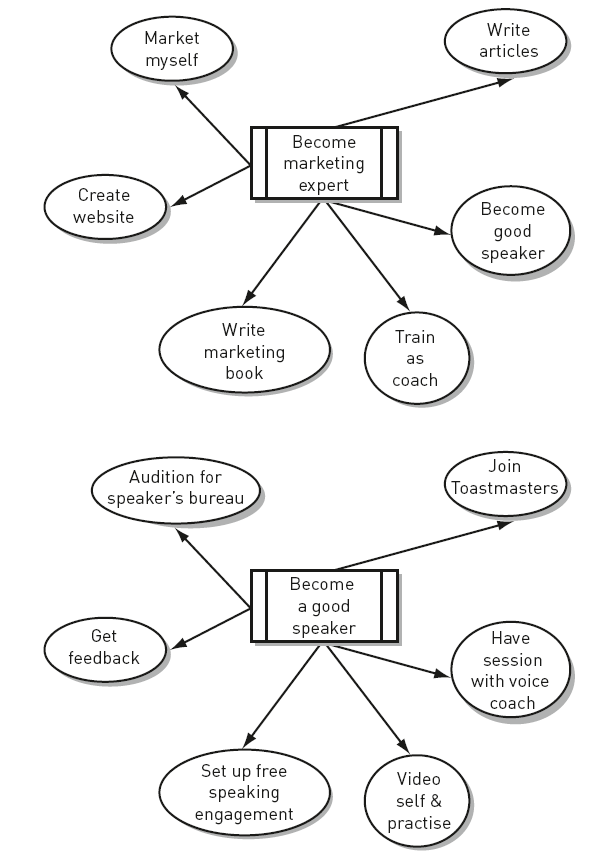

Your visual focus: map your goals

This next step is the creation of a goal map on which you plot all the major steps towards your goal. If it’s a big goal you will want to break it down into a series of additional maps for sub-goals. For example, let’s say that your big goal is to be a publicly recognised expert on marketing, with at least £100,000 a year coming from several streams of income. The steps to that goal might include writing articles on marketing, becoming a polished public speaker, training to be a business coach, writing a book on marketing, creating a website and marketing yourself.

MAPPING PROGRAMS

The goal maps in this chapter were created with a software program called Inspiration (see www.inspiration.com). Another program you might like is called Goal Enforcer (see www.goalenforcer.com). Another mind-mapping program, this one free, is Freemind (see www.freemind.sourceforge.net).

The goal map below indicates these steps in brief form (you’d also want to work out more specific versions). Maps like this are usually organised clockwise, starting at the top right. So, in this case, your first task would to write articles, the next would be to become a good speaker and so forth (although, of course, some of these tasks would actually overlap). While this chapter has emphasised not getting too hung up on deadlines, in this case most of the steps are within your control so you could attach some target dates or time frames.

You can also treat each of the steps towards that big goal as a project, and create a project map for each one. A sample for the step “Become a good speaker” is shown below the “Marketing expert” map, with the first task being “Join Toastmasters”, the next “Have session with voice coach.” Again, you could add dates and more detail.

Time to draw your goal map

Your turn. Whether you use software or just draw the map on a sheet of paper with pen or pencil, rough out a goal map for the goal that excites you the most. You can harvest all the information that you came up with in this chapter to help you plot out the key sub-goals you will need to achieve in order to reach the main goal. Then, as you continue to work through the book, draw goal maps for each of these sub-goals, being more and more specific about exactly what you need to do, how, and when. If you prefer, you can read the rest of the book and then do your goal maps as part of the final chapter, “Putting it all together”, but I highly recommend doing at least a rough version now.

What’s next?

By identifying one or more of your goals and understanding how to overcome the usual flaws in goal setting, you have taken a crucial first step in bringing a laser-like focus to your trip towards success. In the next chapter you’ll learn how to change your time patterns so they totally support your progress.

Website chapter bonus

At www.focusquick.com you’ll find an audio “future interview” guided visualisation. By imagining what things will be like when you have achieved your goal, and in your imagination answering a few questions, you will get important clues about the best way to move forward.