Below the Line

The classification of “below the line” refers to the staff, crew, and equipment suppliers who are literally below a line on a production budget. The people who are above the line are the writer, producers, director, and actors. The “above the line” costs are—once negotiated—set in stone. The below-the-line costs are malleable (although there are union minimum salaries established) until production starts, and therefore the producer and unit production manager (UPM) will do their best to maintain cost control.

Yet those people are no less valuable. They are the ones with whom the director works during production and postproduction on a daily basis. They are your crew—the ones who make your vision become a physical reality. They light the set, they carry in the dolly track, they hold microphones above the actors’ heads, they download your footage. They work very hard, over very long hours, and we couldn’t make any wide-distribution media product without them (except for you making a YouTube video at home with your mom running the camera).

YOUR BACKUP TRIO

The three crew people who “have your back” the most are your 1st AD, the DP, and the script supervisor. In postproduction, the editor is your partner in the editing process, and we will talk more about that in Chapter 14. Each of these people fulfill very specific functions under your direction with the goal of helping you achieve the best possible outcome. We talked about the 1st AD in Chapter 5, recounting how a good 1st AD is your logistics assistant in prep, and the lieutenant to your general on set. The AD position is not generally perceived to be a “creative” one, but rather a nuts-and-bolts one. However, there certainly are creative individuals who take on this task and can offer you suggestions as to how to shoot something more efficiently or even just … better. Those ADs have a director’s sensibility. Be forewarned though, that if you are an AD hoping to move into the director’s chair, the industry bias is against ADs: many believe that they can’t be leaders and don’t have the creative vision component because they’re below the line and they’ve spent their careers dealing with logistics without final authority.

The script supervisor’s job is to keep track of the correlation between the script and what is shot. She describes each shot, either on paper or on a laptop, and indicates which takes are preferred after consulting with you. The “scriptie” also makes note of the lens size, the camera roll number, and the sound roll number, so if a shot gets “lost” on its journey from production to postproduction, it will be easier to locate. But the most important facet of the script supervisor’s role, as it relates to the director, is as a “second eye,” another person watching the shot. She is usually someone who has been on a multitude of sets, has observed much filmmaking, and knows when something is good or not. In terms of quality, she will not express an opinion unless you ask for it. But if you need to talk something through, the script supervisor is an informed and helpful resource.

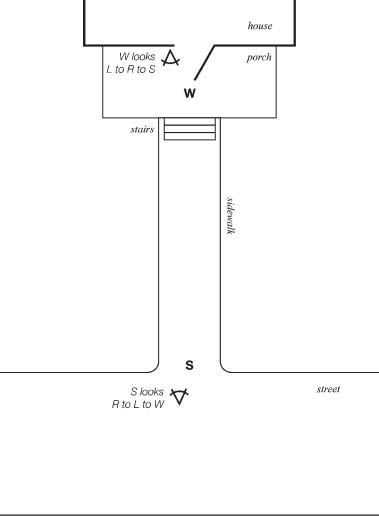

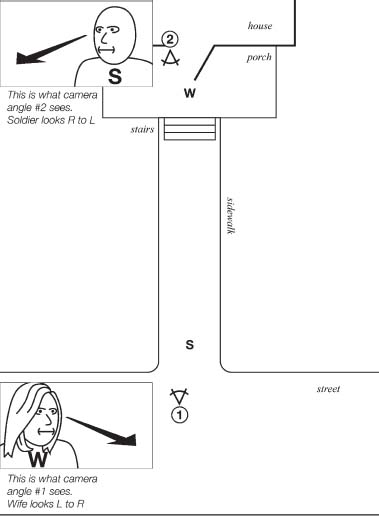

The other function she performs is the technical one of making sure you don’t cross the line when shooting. The “line” is a figurative one that ensures that when your footage is cut together, it will appear that Character A and Character B are actually looking at one another. This is more difficult than it sounds, because each shot is recorded separately—perhaps not even in the same space and time. Picture two people facing each other, and in the rectangle of your frame, Character A (let’s call her Alice) is looking left-to-right to Character B (Bob) who is looking right-to-left. See Figure 11-1.

FIGURE 11-1 Character A (Alice) looking left-to-right to Character B (Bob) who is looking right-to-left.

The “line” would run through the center of their figures, best seen if you imagine that you are looking at them from overhead. See Figure 11-2.

In its most basic form, the important thing to understand is when you are cutting between the close-ups of Alice and Bob, they need to look at opposite sides of the frame to create the illusion they are talking to each other. So Alice looks right, and Bob looks left, and the audience believes they are facing each other and talking. See Figure 11-3. When you shoot the close-up of Alice, put Bob on the right side of camera (“camera right”) and vice versa. See Figure 11-4. Seems simple enough, until Alice and Bob move around the set, and leave their cozy face-to-face position. Then how do you know where the line is?

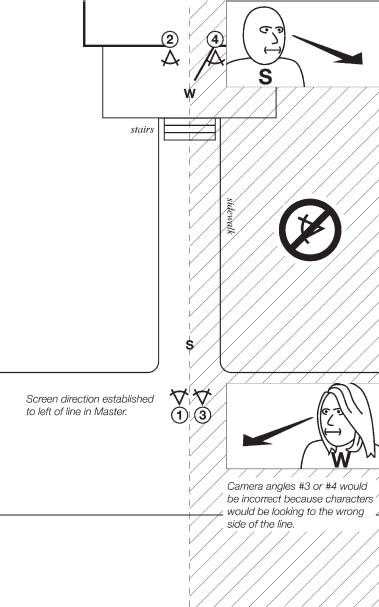

What you have to do is cut the scene together in your head while you are shooting it, so you know which shot you will be cutting from and which shot you will be cutting to. If a character looks camera right to the other character, you would set up the reverse shot in the opposite direction. (Character A looks right, Character B looks left.) For example, in our ongoing story of the Soldier and Wife from Chapter 7, we know the line was set up in the master so the Wife looked right to the Soldier, and the Soldier looked left to the Wife. See Figure 11-5.

The camera angles on the diagram show that although the first shot is next to (or over the shoulder [OS]) of the Soldier, the lens is seeing the Wife, who looks camera right, and the camera next to/OS the Wife depicts the Soldier looking camera left. See Figure 11-6. So it would be incorrect to place a camera on the other side of the line, because then the Wife would look left and the Soldier would look right. (Stick withus here; we know it’s confusing, but once you get this, it’s easy.) See Figure 11-7.

FIGURE 11-2 An aerial view of Character A (Alice) looking at Character B (Bob) with an imaginary line running through their bodies.

FIGURE 11-3 Character A (Alice) looking left-to-right.

FIGURE 11-4 Character B (Bob) looking right-to-left.

FIGURE 11-5 The camera and actors’ positions and in which direction they are looking.

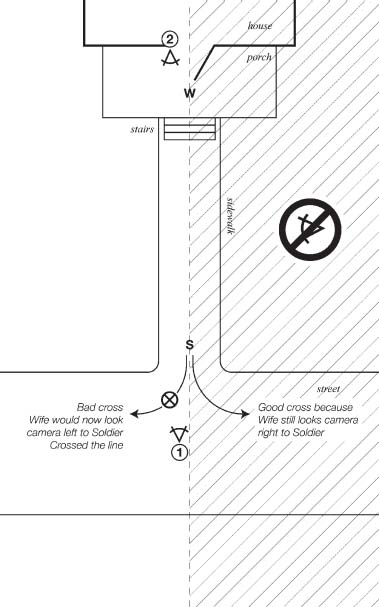

But what if the story took a turn, and the Soldier decided he wasn’t ready to reunite with his Wife, and he wanted to walk away? He could turn 180 degrees and exit, and because he’s on the same plane/trajectory, nothing would change. The Wife would still look camera right to him. He could choose to walk off down the sidewalk to his right (which is also camera right). Again, because the Wife would still look right to him, that is acceptable blocking. But if the Soldier went to his left and crossed camera, the Wife would no longer be looking camera right. She’d be looking camera left, and that is crossing the line. See Figure 11-8.

FIGURE 11-6 The camera and actors’ positions as well as what the camera sees.

FIGURE 11-7 The incorrect camera placement. It demonstrates “crossing the line.”

At that point, the director has three options. The first is to let it be incorrect. We advise against this option, because it’s jarring for the audience when the scene is cut together. The audience registers subconsciously that the Wife always looked camera right to the Soldier, so to have her suddenly look left makes it seem wrong. The second option is to move the camera (dolly) left with the Soldier, always keeping him on camera right. So the looks stay in the same direction, even though the actors have moved. The third option is to show the Soldier crossing the lens, and then shoot another shot of the Wife’s close up and have her look camera left. That way, when it’s cut together, and the audience sees the Soldier cross the lens, and then the next shot is of her looking left, it still cuts together, and everyone follows the flow and the story.

FIGURE 11-8 The two ways the Soldier might cross and why one cross maintains the correct screen direction and the other does not.

Most directors will choose option 2 when shooting a scene in which the actors move so as to maintain the established screen direction. Remember, as long as the characters are looking in the same directions (Wife looks right, Soldier looks left) throughout the scene, it will cut together seamlessly. It doesn’t matter so much exactly where they are but rather that the looks are consistent. So while you are shooting, keep in mind how the scene will cut together—which shot you are cutting from, which shot you are cutting to, and know that as long as your characters are consistent—or you show the change in screen direction—all will be well.

It sounds complicated, and it can be—especially when you are shooting a party scene, or a Thanksgiving dinner scene, or any scene with multiple characters who move around within the set. One of Mary Lou’s mentors, Michael Lembeck, told her, “You’re not a director until you’ve shot a poker game.” But you will have done your blocking and shot listing in prep, and you’ll feel confident that you have a handle on it because you have indicated in your script which shot you anticipate using on every line. And your script supervisor will help you keep track of this line, or screen direction, especially if the blocking deviates from the way you have planned.

The other person who can assist you in this is the DP, who is—in addition to other skills—very aware of screen direction. If you question whether you’ve crossed the line, it warrants discussion with your script supervisor and DP. The DP will also help you place the cameras and the actors to get the shot with the correct screen direction. For example, if you need a character to look camera right (as the Wife does), then you would put the actor playing the Soldier to the right side of the camera, which means the camera is on the actor’s left. Or if it’s an OS shot, the camera would again be on the actor’s left side, looking over his shoulder and incorporating his body in foreground (fg), but most of the frame would be filled by and focused on the Wife. See Figure 11-9. If, however, you make a mistake, and put the camera on the right side of the actor, that would make the Wife look left to the Soldier, which would be crossing the line. See Figure 11-10.

Your script supervisor will help you keep track of this line, or screen direction, especially if the blocking deviates from the way you have planned.

FIGURE 11-9 The camera placement for the over the shoulder (OS) shot.

FIGURE 11-10 The correct and incorrect camera placement for the close-up in order to maintain correct screen direction.

No matter how long a person has been directing, these questions of crossing the line continue to come up, especially in a scene in which the blocking is complex. When that happens, imagine cutting the scene together and what the previous shot screen direction is. The difficulty happens when you haven’t yet shot the previous shot because in the shooting order, lighting takes precedence. As you may remember from Chapter 8, you ask your DP to light the widest shot (probably the master) in one direction and then continue lighting in that same direction. After you and the crew have lit and shot everything in one direction, you’ll turn around to shoot in another direction. If, however, you are not on one axis, but looking in all four directions, the screen direction becomes complicated. Just know that you can discuss it with your script supervisor and DP and agree on the correct looks. But sometimes you end up shooting a close-up “both ways,” meaning that you do it twice, once with the actor looking right, and once with the actor looking left. Then you know that in the editing room, you are protected and the film will cut together.

The DP is really your creative partner on set, helping you bring to life what was previously just in your head. He may use a viewfinder to set up a shot prior to bringing the camera to set or may use an application, like Artemis, for the same purpose. But you will discuss what the shot is exactly, based on your vision. You do not have to tell the DP which lens to use. Just describe how you “see” it. You might say something like, “I see this as starting with an empty frame, then when Character A enters, dolly back with her to pick up Character B in foreground, becoming an over. Long lens, kind of moody.” Your DP may have questions or suggestions. But at that point, you step out of the way to allow the DP to get the grip, electric, and camera crews working on setting up the shot. Once you see that cameras are in place, step back on set to watch the shot and refine it with the camera operator. After the lighting is complete, you’ll do a “second team and background” rehearsal, so the camera crew practices the shot, the DP can check lighting, and you can make sure that when the actors are called to set, all the physical elements are in place and ready.

Prior to working together on set, you will have interacted with the DP in prep. As you begin to block and shot list, you can talk to the DP about what you’ve planned and solicit an opinion. You should consult with your DP about your planned camera placement and whether you need to order special equipment to achieve the shots. The DP will also, hopefully, have the time (if not currently shooting the previous episode) to survey locations with you, in order to talk about logistics and staging the scene in backlight. This means the actors are facing away from the sun, and the DP can light their faces in individual and subtle ways—for the sun is definitely not a subtle front light. It flattens the planes of faces and makes the actors squint. Not a pretty sight. But when the sun is behind the actor, it gives a “hair light,” or glow on the shoulders and top of the head, which is attractive and separates the actor from the background in this two-dimensional presentation. The DP and the gaffer will either work with an old-fashioned compass on the technical scout, or use some new smartphone applications, like Helios, which gives you precise information when you’re asking a specific question, such as, “This scene shoots next Thursday, third scene up. We anticipate arriving at this location at 2:00 p.m. Where will the sun be then?” Once you have that information, you may want to adjust your planned blocking so that the actors are in the best light, and the shoot goes more quickly and easily because it is staged in backlight.

The main thing is to foster a creative partnership with your DP, who will be the one lighting the set and helping you achieve your desired look. The DP will take your idea and “make it happen,” using knowledge and experience to light the set appropriately, communicating with the lighting and grip crews to place lamps and then flag them off to be extremely specific about each light. Because here—just as in every other aspect of filmmaking—more specificity means better work.

The DP is responsible for the “picture” part of “motion picture,” which is where this visual medium started. The DP creates mood by lighting and oversees the framing of the shots. If you are not strong in using the camera well, the DP can be an invaluable asset. Most DPs advance to their position after having previously been a camera operator, so they are extremely familiar with the equipment and what it can do, plus they are artistic in nature themselves. If, on the other hand, you feel confident in this area, it may work out that the DP is simply suggesting refinements and backing you up in the case of a mistake in crossing the line or forgetting a shot. The DP also supervises the camera operator’s framing and the 1st assistant cameraperson’s focus ability. If you are the type of director who is on set with the actors, not sitting at the video monitors (which we hope is true), the DP will watch the monitor and let you know if there are any technical difficulties, like soft focus. The DP continues to oversee the picture quality in postproduction, when he supervises the color correction of the digital final product to make sure that the show is finished in the intended way.

If the AD is your lieutenant, the DP is a captain, because many of the crewmembers report to directly to the DP. The electric, grip, and camera departments are under his supervision. No one in those departments is hired without the DP’s consent and all consider him to be their boss. So in order for you to command the set, it is necessary to have a good working relationship with the DP and share creative sensibilities.

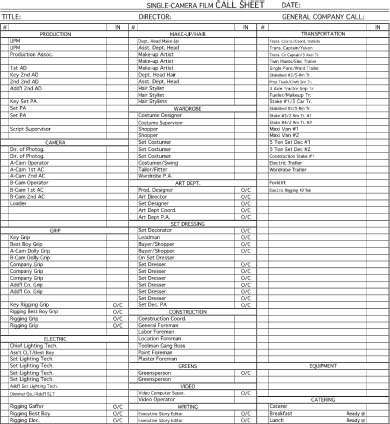

Everyone on the crew and staff is listed on the daily call sheet. We discussed the front of the call sheet in Chapter 5, when we talked about how the 2nd AD lists actors’ call times and daily script requirements such as props and wardrobe. The back of the call sheet lists every position needed for that day, and the name of the person who will be doing the job. See FIGURE 11-11.

Call everyone by their name. Smile at them and interact in a personal and interested way. Ask their opinion when you have a question pertaining to their area of expertise. Gather them in; enlist their support in achieving your vision. Convince them to have the same enthusiasm for this wonderful adventure that you do.

For a standard TV show or feature film, the staff and crew listed there total about 120, including some of the writing and postproduction staff. It is to your advantage to learn everyone’s names and positions in order to communicate clearly and inspire everyone to feel like a vital part of the organization—which they are. Bethany always conceives of this concept as a long line of interconnected cogs. The director is the one at the front, pulling everyone along and leading the way. But the director is the same size cog as everyone else, because if any one cog falls out of the line, it can go nowhere. So everyone is of the same importance. When that is your philosophy, it will be demonstrated by your actions: you will call everyone by their name. Smile at them and interact in a personal and interested way. Ask their opinion when you have a question pertaining to their area of expertise. Gather them in; enlist their support in achieving your vision. Convince them to have the same enthusiasm for this wonderful adventure that you do.

FIGURE 11-11 The back side of a blank call sheet.

So let’s talk about these “cogs” and what they do. We have already discussed ADs, the DP, and the script supervisor. Here are the rest of those positions, listed by call sheet order.

Camera Department

Camera operator: Composes and executes the shot using the picturerecording device, whether the medium is film, tape, or digital. Figure 11-12 shows Bethany discussing the composition of a shot with A-Cam operator Ben Spek on the set of Brothers & Sisters.

1st Assistant Camera: Focuses the camera lens during the shot; supervises the physical operation of the camera.

2nd Assistant Camera: Keeps the camera log, noting duration of each shot and the physical statistics (type of lens, focal length), does the slate (you know, the board that is slapped shut to identify and signal the beginning of the take), organizes and protects the equipment.

Loader: Makes sure there is film (or whatever) in the camera, also known as “stuffing the turkey”; makes sure the recorded medium gets to the transportation department at the end of the shooting day so that it may begin to be processed.

Digital Technician: Watches monitors to make sure the picture quality is acceptable, adjusts gain and balance on the hard drive as necessary; this is an optional position if the DP wants to handle this himself.

Trainee: Someone who wants to learn!

FIGURE 11-12 Bethany discussing the composition of a shot showing actor Cantrell Harris with A-Cam operator Ben Spek on the set of Brothers & Sisters. (Brothers & Sisters trademarks and copyrighted material have been used with the permission of ABC Studios.)

Gaffer: Oversees the electrical crew and sets lights; the DP’s second-in-command.

Best Boy: Executes gaffer’s instructions; may scout locations on behalf of the electrical crew and prepares accordingly, ordering equipment and manpower; next in command to the gaffer.

Lamp Operator: Moves lights into position; may be four or more on crew.

Genny (Generator) Operator: Supervises the power source.

Rigging Crew: Lays cable and prepares sets and locations electrically ahead of time; hangs and prerigs lights in the pattern dictated by the DP; consists of a gaffer, best boy, and lamp ops.

Grip Department

Key Grip: Supervises the “workmen” of the crew; building and facilitating camera and electric crew requirements (for example, flag lamps and lay dolly track for the camera); is the go-to guy for set problem solving.

Best Boy: Second in command, may scout and prepare locations, ordering equipment and manpower.

Dolly grip: Physically pushes, pulls, and otherwise manipulates the dolly to achieve the shot.

Grips: Does any physical labor on set, can be known as “hammers,” may be four or more on crew.

Rigging crew: Prepares locations and sets ahead of time, often by “hanging blacks” to block out windows.

Sound Department

Mixer: Operates the recorder to capture the dialog separately from the video or picture, supervises the sound crew.

Boom operator: Physically holds a pole (boom) with a microphone attached over the actors’ heads, sound is carried via cable to the recorder; can apply and adjust wireless microphones (“mics”) to the actors if that is the method chosen by the mixer.

Cable operator: Facilitates the cabling necessary to connect the various sound equipment pieces.

Playback operator: Plays whatever music or video is required for the scene.

Coordinator: Choreographs scripted stunt action in consultation with the director; hires the stunt performers, supervises for safety, and effectiveness during the shoot.

Casting

Director(s): Consults with director/producers on casting concepts, sends out casting breakdown, listing which parts are available and their physical requirements, initiates contact with talent agents and sets up auditions, culls the best choices, supervises producer session, point person for network/studio approvals, negotiates actors’ deals.

Assistants: Researches actors’ availability, runs camera during sessions, answers inquiries, and files submissions.

Background Casting

Coordinator: Casts extras, or background artists who populate the scenes with the actors.

Wrangler: Supervises the extras cast during the shooting day.

Choreography

Choreographer: Designs dance sequences and teaches it to the actors/dancers.

Associate: Illustrates the moves for the dancers and supervises their physical welfare during the shoot.

Special Effects

Supervisor: Designs and creates unique physical happenings of the script; often uses water, fire, smoke, blood, explosives; generally a team of multiple SPFX (special effects) artists are needed. (Known as the “wizards” of filmmaking, the SPFX team works in and with production and their contributions are on set, not in postproduction.)

Visual Effects

Producer/Supervisor: Designs and creates VFX (visual effects) of which just one element is in production and the other half of the equation will be created in postproduction; often uses “green screen” or “blue screen” in production, which in post becomes an artistic rendering of whatever background or environment is needed, which is joined to the production footage. (Depending on the project, the VFX team could be three people or three hundred. There are many subspecialties of skills on the team, depending on the methods used. For example, if your VFX uses miniatures, your team could be comprised of modelers who sculpt or build the tiny set piece. If you’re making a product like Lord of the Rings or Avatar, your specialty crewmembers would include computer artists and animators.)

Makeup and Hair

Artist: Designs appropriate look and style in consultation with actors and director to augment character presentation; generally, there is a head of each department and assistants reporting to the head; besides being skilled artisans, makeup and hair crewmembers must be ad hoc psychologists who interact with the egos and vulnerabilities presented to them by the actors every morning in the makeup trailer.

Costumes/Wardrobe

Designer: Creates the clothing “look” for each character; head of the department, will shop or originate designs.

Supervisor: Oversees logistics, including most communications with production.

Costumers: Dresses the actors; often assigned to individuals, so a large cast requires many costumers; some specialize in prep and being “on the truck,” that is, keeping track of inventory and cleaning, others are “on set.”

Seamstress/Tailor: Performs repairs and fitting adjustments to the costumes.

Art Department

Production Designer: Designs the sets and coordinates the overall “look” and color scheme of a production.

Art Director: Oversees communication to and from the art department; may coordinate research.

Set Designer: Creates the blueprints and double-checks dimensions and other set requirements.

Coordinator: Facilitates communication.

Graphic Designer: Designs any logos, specialized identification needs, video displays and prop paperwork.

Set Decoration

Decorator: Chooses all furniture and decorative objects in a set in consultation with the director and production designer.

Set Dec Buyer: Shopper.

Leadman: Responsible for the logistics and physically getting the set ready.

Dressers: Move furniture and place set dressing; prepare sets which have been previously shot so everything matches.

On Set Dresser: Works in production to move furniture and objects to make way for the camera or equipment and then reset to match.

Properties

Prop Master: Procures or has made any object that an actor/character physically touches; consults with director for choices.

Assistants: Handle props and reset them after takes; often called upon to creatively rig or find props when it’s a last-minute request; can be two or more on set.

Buyer: Shopper.

Paint

Coordinator: Works with the production designer to obtain and furnish sets with required paint.

Leadman: Oversees crew that paints the sets.

Scenic: Specializes in designs (murals, etc.).

Greens

Head: Supplies and oversees care of plants, flowers, trees, and grass, whether natural or synthetic; places greens on sets.

Locations

Manager: Seeks and finds practical locations that visually tell the story and fit within the producer’s budget, negotiates all contracts and supervises any preparation.

Assistants: Troubleshoots on set during production; handles logistics in prep.

Crafts Service

Head: Provides food and drink to cast and crew; cleans up any spill or mess on set; may provide first aid service if medic is not specifically assigned.

First Aid

Medic: Provides first line of defense in case of injuries.

Production Office/Accounting

Coordinator: Oversees staff and logistics.

Assistant: Helps the coordinator.

Production Assistants (PAs): Do diverse tasks from getting coffee to copying scripts to answering phones.

Accountant: Supervises all expenses and income; writes the budget.

Payroll Accountant: Cuts and delivers checks—the one the whole crew likes to see on Thursdays!

Clerks and assistants: Do office work; bigger budget shows need more manpower.

Producer assistants: Answer directly to individual producers and assist them in any way necessary.

Transportation

Coordinator: Procures “picture cars,” which will be seen on film, oversees the department, making sure the trucks that carry a production’s equipment are where they’re supposed to be on time; choreographs pickups of others who may need transportation, especially actors, directors, and producers when on a distant location.

Captain: Coordinates schedules and equipment; immediate boss of all the drivers.

Drivers: Drives assigned truck, also ferry actors and crew from place to place; can be a crew of ten (minimum) to thirty.

Catering

Chef: Cooks and supplies whatever meals are needed; typically both breakfast and lunch.

Assistants: Prepares and serves under the chef’s direction.

Coordinator: Oversees the building of sets; works closely with production designer.

Foreman: Responsible for workers’ safety and daily output.

Carpenters: Builds the sets; usually at least four on crew.

Additional Labor

Teachers and social workers (if child actors are working), and animal wranglers (to supply and train animal actors); could also be specialized labor such as a crane driver.

Whose Job Is It Anyway?

![]()

Choose a partner. Make flashcards from the duties column in the previous list of jobs. Put them in a hat. Play a game to see whether you or your partner can name the right job title to go with the job description. To play a more advanced version of this game, describe scenarios of things going wrong on the set. Your partner has to figure out which person or persons will be needed to resolve these problems.

Often, crewmembers are identified literally and figuratively by their job description. First, they often own the equipment and rent it to the production company as a means of augmenting their income and controlling the viability of the product. So the transportation coordinator may own the trucks, and the Steadicam operator may own his own rig. (If a crewmember does not own the equipment a production wants to use, it can be rented from a company that specifically provides material to the production industry.) Second, most crewmembers are known by their first name, and their new last name is their position. So you may find yourself on set calling out for “Frank Greens” or “Joe Props.” People take pride in what they do. No disrespect is intended by referring to them this way; it’s just a shorthand communication method used on set.

As you can see, it takes many cogs in our lineup of crewmembers working together to turn out the finished product that serves your vision. You—the director—cannot do it alone. You need the help of all of these departments—all of these people. They are all experts in their specialized fields; once they have been enlisted to service your vision, they will work very hard to make it a reality. And when you appreciate their efforts, you truly are a team.

Most crewmembers are known by their first name, and their new last name is their position. So you may find yourself on set calling out for “Frank Greens” or “Joe Props.”

Insider Info

How Do You Interact With the Director?

I can’t tell you how happy it makes me that Bethany and Mary Lou are introducing you to the role of the script supervisor. Many film courses don’t teach what the script supervisor does, so as a new director, when you first arrive on set, you may find yourself wondering, “Who is this person and why are they still talking to me?” I am the person who sits next to you. I am your extra set of eyes and ears: the recorder and the reporter!

As a script supervisor, it is my intention to make the director’s life easier. It is my duty to ensure that we maintain the continuity and integrity of the script, keeping clear and concise logs, as well as noting your preferences and comments after each take or setup.

Before I meet you on set, I will have been given the script in order to do a breakdown, which will be distributed to all key departments—wardrobe, hair, makeup, props—so that we are literally “all on the same page.”

I track the specific days in which the story takes place (Day 1, Night 1, Day 2, Night 2, etc.) as well as the time of day. This tracking keeps us in agreement and is critical for maintaining the continuity. For example, if the script says, “The clock strikes midnight,” it’s my responsibility and that of the prop department to make sure that the clock reads midnight!

Once on set, I note dialog changes, screen direction, and camera angles, as well as wardrobe, hair, makeup, and prop details for matching. Some matching notes, for example, would be: “Hair style changes—in front of the ear, behind the ear? Costume changes or alterations—buttons up, buttons down? Specific props—gun in the right hand, gun in the left hand?” Or say there’s an accident. At this point in the storyline, would the bandages be on, or would the bandages be off? If the director turns to me, I have the answer.

The director’s work method and temperament dictate the general tone on set. A lot of my interaction becomes intuitive as I get to know the director better. My general rule for working with a director for the first time is to ask, “How do you like to work with the script supervisor?” More often than not, most directors don’t have too many specifics, except for, “Make sure we’re covered before we move on.” Equally as important is the question of the handling of the dialog. If an actor speaks a line incorrectly, I let the director know. I always ask the director, “Do you prefer to give the actor the note or should I?”

Besides the script breakdown, on-set matching and continuity, script marking, and various logs, I am also responsible for reporting to the Production and Postproduction departments an account of the day’s work, what has been completed, and what we owe.

What Do You Wish Directors Knew About Your Job?

Again, it’s my job to ask questions. I’d rather feel stupid asking a question than be stupid by not asking! More often than not, the thing I’m questioning is a legitimate concern.

As the director, you’ll be bombarded with multiple questions at one time. You may look to your script supervisor for an answer. As we furiously refer to our notes, may I kindly remind you that generally we only get a few days to prep. Be patient with us. The script supervisor’s job is far more complicated than you may have imagined.

What Advice Would You Give a Director Who is Starting Out?

When you’re first developing your craft as a director, it’s safe to assume you’ll be directing low-budget/no-budget “labor of love” projects. When you are told you don’t have the money to hire a script supervisor, I implore you to emphatically respond, “Find the money.” Trust me, you’ll save money in postproduction, and if you’re saying to yourself, “I am post,” again, trust me on this one.

Also, as we move further and further from film into digital, there are no “circles” or “print takes” per se. You’ll want to see everything—and that is the beauty of digital. Here’s where the script supervisor can be of great service to you. Give specific notes of what worked, what didn’t, and what your favorite “starred (best) take” was, before you move onto the next setup.

And my biggest piece of advice is to recognize and appreciate your cast and crew. I can’t tell you how much a simple “Thank you, and good job!” inspires us to work harder for you.

Nila Neukum

Script Supervisor

South of Nowhere, Hellraiser: Revelations

Vocabulary

boom

cross camera

cross the lens

cross the line

cut together

extras

looks

screen direction

slate

SPFX

viewfinder

VFX