Organizing the Shoot with the First Assistant Director

In an average one-hour single-camera production, you have about 52 pages of script that must be shot in 7, 8, or 9 days, depending on the budget. With a half-hour single camera show, you have about 38 pages that usually must be shot in 5 days. How do you decide what to shoot on what day? How do you fit it all in?

Those decisions are made during prep. There are many factors to juggle, and you—the director—are mostly focused on the creative aspect of blocking and shot listing, so you need someone to focus instead on the logistics. That person is the first assistant director, or 1st AD. (There is also a 2nd assistant director, and a 2nd 2nd assistant director, and there are production assistants on staff, too. But more on that later.) He is your right hand, the person who has your back, the one to whom you tell every thought and plan you have, the one who disseminates the information and gets everything you need in place so that you can actually do your job. The 1st AD is the conduit between production and you who makes sure that every department head knows what you require ahead of time. You can and will have those kinds of conversations directly with the department heads, but the AD will follow up and make sure that the crane or the car or whatever you need is there for you on the shooting day.

THE SERVANT OF TWO MASTERS

Your AD will also serve as your sounding board, your sympathetic shoulder (though hopefully you will do no crying on it), and will ideally be your friend—in the sense that he will tell you the truth. Because there are so many personalities at play in the course of prep and production, there is sure to be some interpersonal drama. The AD is usually tuned in to those undercurrents and can help you navigate them. You need someone to be your eyes and ears, someone who tells you what’s really going on because everyone else will defer to your position as director. The AD is the one in the middle, the one who is considered part of the crew, yet is close to you, too.

Everyone knows that the AD is the gateway to accessing the director, so—in addition to logistics—the most important function of the AD is to keep the communication flowing in both directions, that is, to the director and from the director.

The AD also communicates with the producer, basically reporting what is happening with you and your decisions. Be aware that the AD is hired by the producer and therefore is loyal first and foremost to that boss. (Again, the entity with the money is the ultimate boss.) And in episodic television, the AD is hired for the whole season; a director comes in for just one episode at a time. So the AD may find him- or herself between a rock and a hard place: between the needs of production and the needs of the director, if they are not in sync. (In a feature or a long-term one-off, like a TV movie or pilot, the synergy between the director and AD is more pronounced. The AD will truly be the right hand of the director. In episodic television, however, the AD’s loyalties may be more divided.) Basically, the AD is hired to be helpful to you, but he is also hired to keep an eye on you.

Everyone knows that the AD is the gateway to accessing the director, so—in addition to logistics—the most important function of the AD is to keep the communication flowing in both directions, that is, to the director and from the director.

The strength of your relationship with your 1st AD is dependent on your personalities and whether you have a symbiosis of philosophy. Essentially, do you get along? Do you see eye to eye?

If you are hired to be a director on a new project, you will have the final say in hiring the 1st AD. You can then look for an assistant with whom you feel comfortable in representing your interests, as that is essentially what an AD does. If, however, you are one of many directors to work with an AD within the schedule of a season, you will be meeting a stranger and hoping to quickly create a respectful working relationship that functions with clear communication. If you work to make an ally of the AD, you will be glad you did so during production. If, on the other hand, you two are at odds, it will be detrimental to you, because the crew perceives the AD as one of them, and relationships can quickly deteriorate into an “us vs. them” confrontational paradigm. There are many of “them” (the crew) and one of you. So regardless of whether you hired the AD, it is in your best interest to create a good partnership with that person.

Basically, what we’re saying here is that the AD is hired to be helpful to you, but he is also hired to keep an eye on you.

If you are a freelance director, you will be introduced to your AD on the first day of prep. Together, you will proceed to the concept meeting, hopefully having had an opportunity to discuss your thoughts on that script. The 1st AD runs all of the meetings; that is, he is the moderator. The 1st AD will say, “Welcome to the concept meeting for (name of show) episode # _________________, written by ____________________, directed by (you). Let’s begin with scene one.” And you and all the department heads, along with the producer, start at the beginning. You proceed, with the 1st AD leading the meeting, to work your way through the script, discussing potential solutions to the script requirements. You can interject information as the 1st AD leads the meeting if it is needed. The department heads will also have questions that only you can answer. The 1st AD will defer to you when these kinds of inquiries come up.

GENERATING AND JUGGLING THE SHOOTING SCHEDULE

After that first concept meeting, the next job of the 1st AD is to create a shooting schedule, which tells everyone involved in the production what is to be shot each day, and what elements are necessary. Which set will you be on? What props are needed? What actors are working? Of course, the shooting schedule can be created only if the script exists because that is the template from which everyone works. Very often, in episodic TV, the script is not yet written on the first day of prep. Obviously, the more time that everyone has to prepare, the better the shoot will go. If the writers are late in delivering the script, the preparation time will be condensed. Of course this shouldn’t happen, and in fact the DGA has guidelines specifically to avoid this kind of situation in order to protect the director when she works. The reality is that scripts are often delivered late. But once the script is delivered, the first order of business is to determine what will be shot and when.

The 1st AD breaks down each page of the script into eighths, so a scene might be listed as being “one and three-eighths of a page,” or 2 5/8, or whatever it is. He then “names” each scene by number and a one-phrase description (Larry and Jane meet, Larry and Jane kiss, Larry and Jane break up). He chronicles what specifics are called for in sets and locations, props, wardrobe, special effects, stunts, transportation, and so on.

The ideal shooting day would be 12 hours or less (excluding lunch), and everything would be organized to create flow and the least amount of disruption.

The 1st AD then uses a software program such as Movie Magic to create a schedule by putting groups of scenes together to shoot over the course of each day, which is called boarding the script (because it used to be done by hand, using cardboard strips mounted on a folding board). Once the 1st AD has a tentative board, he will bring it to you for discussion and approval. There are usually many editions of a board as factors emerge during the prep time, which force a reordering of the shooting days. But by the last day of prep, there will be a board/shooting schedule released to staff, cast, and crew that tells everyone what will be shot and when. You will see an example of one in Chapter 8.

The ideal shooting day would be 12 hours or less (excluding lunch), and everything would be organized to create flow and the least amount of disruption. There are many factors for the 1st AD to take into consideration when putting a board together. They are:

Actor availability

Cast regulars are committed for the duration of the shoot, though they may request time off for personal or publicity reasons. If the producers grant a request, then the actor cannot be scheduled to work during that time. Guest actors are booked according to the shooting schedule, so it is incumbent upon the 1st AD to group a guest actor’s work together so that they are paid for the fewest days.

Set or location availability

If you want to shoot at Staples Center, but in the week that you want to shoot, they already have a Lakers game, a concert, and a Kings game, you’ll have to fit in when they have an open time. Or if you want to shoot in a restaurant that is busier as it gets closer to the weekend, you’ll probably have to shoot there on Mondays when they’re closed. If the production designer is building a set, you can’t shoot in it until it’s constructed and decorated. The more locations and swing sets (sets that are new and specifically for this script), the more complicated this juggling act becomes.

Actor turnaround

By SAG and AFTRA agreements, actors are given 12 hours off between completing work on one day and beginning work on the next day. This is called turnaround. So if you finish one day at 7:00 p.m. with Actress A, you can begin with her again at 7:00 a.m. the following day. But if she needs two hours at the beginning of the day in hair and makeup, then the crew call (time of day when the work begins) would have to be when that precall work in the hair and makeup trailer is finished, at 9:00 a.m. If that happened every day of the week, you would be starting your day on Friday at 5:00 p.m. and working through the night. So the 1st AD will try not to end on Monday and begin on Tuesday with the same actress. This sort of thing is a particular challenge on a show with one main lead who is in most of the scenes. Multiply this conundrum by the number of actors in the cast, and you can see that it’s quite a jigsaw puzzle. Appreciate the organizational skills that your AD must have to juggle all this.

Company move

Every time a crew has to pack up their equipment and move from one place to another, it takes time. And time is money. A company move from one stage to another generally requires a half hour. If you have to load everything onto the trucks and move across town, that could take two hours or more. And that is two hours you are not shooting, when you’re trying to complete your scheduled scenes for the day. Two hours of overtime could cost a production company anywhere from $15,000 to $75,000 (or more), depending on many factors. So when putting a shooting schedule together, the 1st AD will try to consolidate company moves by putting all of one location together, then all of the next location together, and so on.

If there are individual scenes in multiple locations, the best thing would be to try to find them all in one basic area, so that base camp (where the trucks park) doesn’t have to move. The equipment could be loaded onto stakebeds (smaller trucks) or the crew could roll the carts to each location. (Equipment is always stored on handcarts that can be wheeled short distances.) On the ABC show Brothers & Sisters, Bethany had one location day in South Pasadena that was a good example. The scenes in the script were a baby products store, a coffee house, an interior college president’s office, and an exterior (night) Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. All were shot within two blocks of each other, and the work was completed in under 12 hours. The baby products store and the coffee house already existed in proximity, and the company created the interior set inside the lobby of the nearby public library, whose steps also served for the night exterior scene. A company move would have rendered that day unshootable.

Amount of work

The 1st AD will divide the shooting days into groups of scenes he thinks can be accomplished in a 12-hour day. The factors taken into account include the speed at which the crew works, the stamina of the actors, the physical demands of the space, and the number of shots planned by the director. If it all adds up to more than can be done in one day, then there are two choices. You can either take more than one day to shoot at a location (perhaps it will be scheduled for numerous days) or you can go to the writers and suggest moving the location of a scene. What you cannot do, as a responsible director, is think that somehow it will just turn out all right. You have to plan during your preparation time how you will make the day, that is, complete the scheduled work on time and on budget.

Important note: More characters require more shots, which require more lighting, which requires more time.

For example, if a script has 11 pages in a restaurant over 5 scenes, that does not seem like a doable day (within the 12 hours). So you might suggest to the writer that one two-and-a-half page scene be relocated to somewhere else. That would make it four scenes, eight-and-a-half pages. That’s still a lot. How many characters are in each scene? If it’s only two, that might be possible. But if it’s more than that, the complications increase. More characters require more shots, which require more lighting, which requires more time.

On a TV schedule, you can usually shoot a maximum of eight pages, though the salient factor is really the number of scenes (and therefore, the number of setups, or individual shots, for each scene) and not page count. If you have more than 25 setups planned, then the day is probably overloaded. When you go to a writer to say, “This day is unmakeable,” the most constructive thing is to propose a solution. Look at your other shooting days. Is there one that’s lighter to which this orphan scene might be moved? Could the scene be moved to a standing (already existing) set? Or could it become a different type of scene and still accomplish the scene’s objectives? For example, could the characters have left the restaurant and finish their conversation walking up to the front door of their house? As long as the intent of the scene remains the same, it is often possible to move locations. Doing so sometimes forces the writer and director to think more creatively about this particular area of production problem solving, which makes for a better show in the end.

Day or night

The top of every call sheet (the day’s schedule and its requirements) lists the exact time for sunrise and sunset because, though film people think they’re in charge of everything, we have not yet figured out how to control the sun. If you have three scenes of exterior day work and one of night work scheduled, you’d better make sure to complete the day scenes before the sun goes down. (You can, however, shoot interior night scenes during the day by blacking out the windows.) The 1st AD will estimate how long each scene might take to shoot and schedule it accordingly. But if there’s a miscalculation, or it takes longer to shoot than you anticipated, you’ll be in a mad race to light a scene with the sinking sun, counting down the moments until you’re forced to concede to a greater authority.

The intuitive

When putting a schedule together, the 1st AD has to take into account this final aspect, which generally has to do with the effort and impression a scene will make. Often, you’ll want to start with the meat of the day (the biggest and hardest scene). As the saying goes, “You’ll be shooting Gone with the Wind in the morning and Dukes of Hazzard in the afternoon.” You’ll take a lot of time shooting an important scene, and the less important one is done at the end of the day in a single, uncomplicated shot as you’re running out of time. The director and the 1st AD will discuss which scenes hold special meaning and which may be more complex than they seem. Although the 1st AD can take into account what is on the page, he can’t read your mind. If you plan a particularly difficult shot or you think it will take longer to achieve the performance you’re looking for, you need to let the 1st AD know so that the appropriate amount of time is scheduled. Peter Weir shared a story about this in an interview in the DGA Quarterly.1 Talking about his movie Fearless, he recalled a moment that stood out for him as he read the screenplay. “There are two men flying on a plane that’s in trouble, that’s going to go down, and one of them, the Jeff Bridges character, says to his partner, ‘I’m going to go forward and sit with that kid up there.’ And then the script says, ‘He moves down the aisle and sits beside the boy.’ It’s maybe an eighth of a page. That was the line that struck me…. When we came to schedule it, I told the AD I wanted half a day to shoot it, which I think was a bit of a surprise. It’s always hard to speak about what interested you in a piece, because it’s often something unknowable. It’s the nonintellectual, the unconscious that’s most important to me.”

The other intuitive part of scheduling has to do with making a good impression. When the producers (and studio, and network) see the dailies (the raw, unedited footage) of your first day of directing, you want them to see scenes that are dynamic with good performances. But you know that on the first day, you won’t yet have a strong working relationship with the actors because you’ll just be figuring each other out, not quite yet committed to trusting each other. You also won’t yet have the kind of working relationship with the crew that allows for shorthand communication and a shared vision of the way you shoot. So those first scenes need to be ones that have strong energy but are not overly ambitious or overly interpretative. They need to be fairly straightforward yet creative. And of course those first scenes need to fit all the other requirements, too, like having available actors and sets!

The shooting schedule lists all the elements needed for each day of shooting. But it is also broken down into more succinct documents that characterize particular needs. The one-liner is a short version of the shooting schedule that lists the scene numbers, the page count, the scene description, the actors needed, and what script day it is in the continuity of the story. (A story may take place in a short time span such as one day, or it may take place over many years. All department heads need to have the same understanding of when the daybreaks are, to plan accordingly. If it’s script day 3 in scene 22, the lead actress should not be wearing the wardrobe from script day 2, scene 21, if the daybreak was at the end of that scene.) The day-out-of-days (DOOD) is a chart that specifies which days of the schedule each actor will work. The AD may also generate a special needs chart, which shows what special equipment or personnel must be ordered for each day (that the company does not normally carry, like a technocrane or a choreographer).

Creating a One-Liner

![]()

Even though this is a 1st AD’s job, try creating a one-liner for a movie you know. Using the script, describe each scene in one short line. Group together scenes that are in the same location or set and have the same actors. Look at the page count for each day. Could that day be made? If not, divide those groups of scenes into the number of days required for shooting. Don’t forget to be aware whether it’s a day scene or a night scene. How many days of shooting do you think the movie required? In what order would those scenes be shot, according to your one-liner?

While you, the director, are spending your nonmeeting times of the prep period blocking and shot-listing, your 1st AD is spending that same time creating the shooting schedule and arranging for the logistics of making that schedule come to pass. But the rest of the prep time is spent together, as you go on location scouts, walk the sets, and attend meetings. (However, the 1st AD is not present for casting sessions.) You will have conducted dry runs of any big set pieces, that is, a large event in the script that requires special advance planning. For example, if you have a scene with a big car crash, you might ask the art department for a scale model of the location and use toy cars to plan your blocking and shot placement. (Don’t laugh! That works really well, as it’s a physical/tactile way of “seeing” the set piece before you have to shoot it.) The 1st AD will gaffe (arrange) anything you need—whether it’s assembling people or toy cars—to make your prep the most thorough it can be.

You and your 1st AD will get to know each other well during prep and develop a relationship that fosters a strong connection during the shooting and production periods.

YOUR RIGHT ARM WHILE SHOOTING

For a one-hour episode, you have seven days of prep. For a TV movie or small feature, you will have three or four weeks of prep. But the day eventually comes when it’s time to begin shooting. You and the 1st AD have made everyone aware of your intentions, and everyone and everything has been scheduled and arranged. If you have done your prep well, you are ready for any foreseeable difficulties. You know how you intend to shoot the script; you have broken down the script for story and character; you know the whole thing inside and out. You are ready, and your 1st assistant director is there to help you begin.

What is important to know now is that the 1st AD is in command of the set, by virtue of being the one to give instructions. We could use a military metaphor here and say that you, the director, are the general, and the 1st AD is your lieutenant, the one who communicates your desires.

Just as the 1st AD runs the meetings in preproduction, the AD also runs the set during shooting. That means the 1st AD will call out what’s to be done and the crew and cast will react accordingly. So the first thing that happens on your first day is for the AD to call out (both loudly and on the walkie-talkie radio), “First-team rehearsal.” The first team is the actors, and the second team is their stand-ins, the people who stand on the actors’ marks (or locations) while the set is being lit. We talk about this more in Chapter 13. What is important to know now is that the AD is in command of the set, by virtue of being the one to give instructions. We could use a military metaphor here and say that you, the director, are the general, and the 1st AD is your lieutenant, the one who communicates your desires.

The 1st AD is the troubleshooter, to whom all departments report regarding ongoing work flow and the obstacles to it. This includes you, the director. If you are facing any difficulties, it warrants discussion with the 1st AD, so he may act as your sounding board and/or your “bad cop” to make things happen. This strategy allows you to continue to be the “good cop” and function as the nurturing leader you are.

So when you are ready for rehearsal, or you want to speak to someone specifically, or you want to begin shooting, you communicate that to the 1st AD, who then in turn communicates it to the relevant parties. Although it may seem dubiously roundabout—why not just call it out yourself?—it’s actually more streamlined. The AD has the radio and can tell the entire crew with one command what you want, and it’s important for the AD to know what’s happening as you think of it, because everyone else will ask him. It’s the way the power structure is set up, and it’s effective.

During the shooting day, the 1st AD is always on set, right by the camera. The 1st AD is aware of everything that is going on and is the point man for all communications, including that from the producers. The 1st AD will make the producers aware of shooting progress or lack thereof and be included in discussions about how to make the day. The 1st AD is the troubleshooter, to whom all departments report regarding ongoing work flow and the obstacles to it. This includes you, the director. If you are facing any difficulties, it warrants discussion with the 1st AD, so he may act as your sounding board and/or your “bad cop” to make things happen. This strategy allows you to continue to be the “good cop” and function as the nurturing leader you are.

The 1st AD is your assistant. And just as you have people above you (the ones with the money; the showrunner/studio/network) and below you (those whom you direct), within the power structure, so does the 1st AD. He reports to the unit production manager (UPM), who is responsible for the day-today operations of the crew, with direct supervision of those below the line. On a production budget, there is a literal dividing line. Above the line people (and therefore, costs in a budget) are the producer, writer, director, and actors. Everyone else and their equipment are below the line. The UPM is in charge of maintaining operating costs per the budget below the line. The UPM is a DGA member, as are you and the rest of the directing staff.

Although productions are shot without being a DGA signatory, it is not recommended for any professional production. The DGA provides a framework for your protection, with legal agreements binding the producing company to abide by negotiated rules. These rules keep you and the rest of the DGA members (and consequently, the rest of the crew) safe from physical risks and poor working conditions. The DGA also negotiates salary minimums and provides health insurance and pension benefits. When you are working with a DGA staff, you know they are well trained in all aspects of production and will capably assist you in every way to achieve a creative final product done in a professional manner.

The 2nd AD needs to be someone with strong attention to detail and a facility for communication. And she is rarely on set, due to the intensity of pulling tomorrow’s call sheet together.

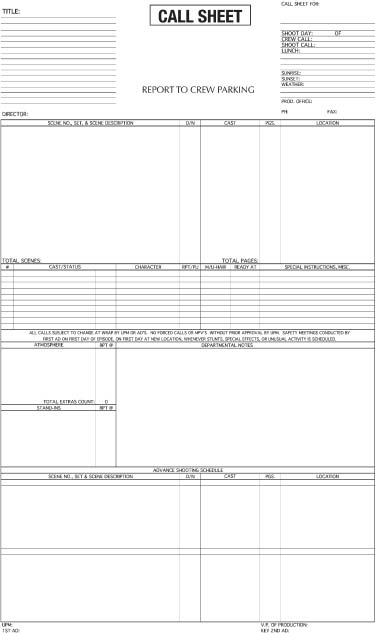

The 1st AD is, in turn, assisted by the 2nd AD, the 2nd 2nd, and production assistants (PAs). The 2nd AD is always looking toward the next day’s shoot, preparing the call sheet, which lists the call (beginning of the day) time, the scenes to be shot, and the personnel and equipment required. See Figure 5-1. This means a lot of time on the phone (in all its incarnations, especially texting) and communicating with the production office. The 2nd AD’s initial preparation is taken from the 1st AD’s shooting schedule and then augmented by whatever daily changes are made due to shifting circumstances (somebody got sick, the director dropped a scene from yesterday, ordering a third camera, etc.). The 2nd AD needs to be someone with strong attention to detail and a facility for communication. And she is rarely on set, due to the intensity of pulling tomorrow’s call sheet together. At the end of the day, she also completes the production report, which is an accounting of what took place: which scenes were actually shot, who worked, what equipment was used, how much film/tape/digital memory was expended.

FIGURE 5-1 The front side of a blank call sheet.

The 2nd 2nd AD is in training to move up the ladder; this job takes place primarily on set. The 2nd 2nd helps the 1st AD set background, which means placing the daily hires of “extras” or “background artists,” who populate the frame to create the human environment of the film. They are the people in the theatre seats surrounding the principal actors or the office people rushing by as the leading lady walks with her leading man. The ADs tell them where to start, where to go, and what “job” they’re doing. For example, a background artist in a lawyer’s office set will be instructed to walk from point A to point B carrying files and a coffee cup and to play the part of a harried underling who is late for a meeting. In short, walk fast, look like you belong there, and arrange to be on camera consistently from take to take when the principal actor is saying a specific line. The 1st AD is in charge, but the 2nd 2nd does the first pass at setting background, training to do it well by the time they are promoted through the ranks to become a 1st AD.

The AD staff also facilitates production in any way necessary: by calling for quiet when the camera is going to roll, by communicating with other departments who need to know how the day is going, like transportation or catering, and by mediating interdepartmental misunderstandings. The PAs also assist in these tasks, and any others—like making a run to Starbucks—that are required. There is also one PA (or sometimes an additional 2nd AD) who mans the base camp. That is, she informs the actors when it’s time to come to set and communicates with wardrobe, makeup, and hair as to what is needed and when. This is a job that requires extremely well-developed people skills and is a great training ground for the vicissitudes of working with 100 highly creative, passionate crew and cast over long hours in condensed spaces. The PAs and the 2nd ADs report to the 1st AD, who is ideally aware of everything happening during the production day.

Though there may be a large AD staff, depending on the show’s budget and size of cast and crew, the director’s primary interaction is with the 1st AD, in part because the AD assists the director during prep as well as production. For the length of time it takes to go from script to completed production, the director and the 1st AD are a team. It is a partnership that is built to serve the director well on a practical level, and a superb AD will be indispensable by backing you up creatively and personally as well.

Insider Info

How Do You Interact with the Director?

The relationship will differ with each project and each director. A director who wrote the script and managed to get the project greenlighted will not have exactly the same needs as a director fulfilling an episodic TV assignment. But in either case, the moment we start working together, my actions and general attitude must be all about figuring out what those needs might be. I do that simply by asking them but also by observing and listening to them very carefully, feeling out who they are and how they like to work. Some directors love the rehearsal process, for example, and some shun it all together, looking for spontaneity instead. Some love the preparation process, spending hours making shot lists and storyboards and taking meetings with department heads; others prefer to keep all that to a minimum, and expect me to handle everything they don’t absolutely have to be there for.

It didn’t take long for me to embrace the idea there are many ways to skin a cat, and I should not judge directors by their methods. Even though directors differ, my job stays the same—with the script as a guiding light, and the budget and schedule as parameters: (1) learn how the director envisions turning that script into sounds and images, (2) communicate that to the cast and crew, (3) monitor as everyone proceeds to facilitate this vision, and (4) rebound whenever an obstacle surfaces, be it the weather, losing a location, or unexpected script rewrites.

Personality very much comes into play as well. None of us can really change who we are, so I warn prospective directors about my relaxed and friendly nature. Some prefer to hire an AD that operates more like a Marine sergeant, but I run the set using humor and empathy, which I find far more productive than shouting orders. When interviewing with a director, I make sure they see the real me, hoping a kindred spirit will recognize and hire me, but I also assess who they are, gauging whether I want to work for them, because in the end, the relationship will be a two-way street, very much like a temporary marriage, and will produce the best results when it works for both us. As in a marriage, trust and respect are the key elements. Regardless of the specific dynamic at play with each director, I make sure to show them the utmost respect and always try my best to tell the truth. It’s admittedly difficult in certain cases, but it’s the only road I know that leads to a good working relationship. When it works, it can be immensely rewarding for both of us and for the project. When it doesn’t, at least you know you gave it your best shot.

What Things Do You Wish Directors Knew About the AD’s Job?

That the best results can be achieved only if they trust us. Most ADs—certainly the good ones—don’t have an individual agenda. We’re here to serve the big picture. We don’t have a line-item budget to spend or outside vendors to please, overtime means little to us, and we don’t get meal penalties. Our only beacons are the script, the budget, and the schedule—in that order, the order they were created. Yes, we came up with the schedule and are keen to defend it, but are also ready to change it in a heartbeat if we see an opportunity to better serve the script. Although others in the crew are responsible for only a specific aspect of the project, the 1st AD is responsible for overseeing everything—just like the director and the producers. It’s something we have in common; it’s what makes us a team, the fact that we’re the only ones focused not on any one aspect of the project but on the entire picture.

But although directors can focus on their vision, we ADs have to actually get on the ground and make it happen, and we can do that well only when the director trusts us to handle it how we see best. When I go to a crewmember to implement something that the director wants, I may not put it to them the same way the director put it to me. The same is true the other way: when I bring a concern to the director, I may not say it the same way it was told to me. I call it English-to-English translation. ADs may act as the set’s nervous system, collecting and sending information up and down, keeping everyone informed of what’s going on at any given moment. But that doesn’t mean we should parrot everything exactly as it was told to us. Good ADs use experience and discretion to relay information in the manner that will most likely lead to the best results. Good directors recognize that and let us go about our business the way we know best. It’s very hard to make a movie—even harder to make a good one—and maintaining a solid trust between the director and AD can only tilt the odds your way.

What Advice Might You Give a Director Who has not Worked in Television Before?

I’ve often heard that film is a director’s medium, and TV belongs to the writer. But I disagree with that perception. There are three storytellers involved in making a movie: writers, directors, and editors, and all three are equally important. The writers are the source: they come up with the story in the first place—without them, you have nothing. The editors are the end user and give the film its final shape: they decide what goes on screen and what is left out. Both are determining steps, the beginning and the end, but it is the director who connects them and who in doing so may have the most important job: to dissect the writer’s words into short individual pieces and then oversee their creation as sounds and images in a way that allows the editor to put the story together in the best way possible. In television, a lot of the groundwork is done by a writer/showrunner, but that’s only because of schedule and financial constraints. Yes, the director’s role is somewhat limited: the lead actors have been cast, the main locations picked, and the permanent sets built. But it’s still left to the director to turn that script into great footage, into what Peter Bogdanovich called “pieces of time.”

The role of the AD is also different in episodic television. Because we are present from beginning to end, guest directors depend on us to get them up to speed and keep them true to the course that the showrunner has set. Trust becomes doubly important during prep days, which are preciously few and during which there is no time to waste. The process may appear to be more challenging than in a movie because here, the director cannot choose who the AD is, but I actually find it liberating—we’re stuck with each other, so why not make the most of it. Veteran TV directors know this and are easier to work with. As in a movie, it’s still my job to quickly assess who they are and what they want, and the director is still very much in command. But in episodic TV, I will often know things about the cast, the crew and the script that they don’t, and by putting their trust in me, they only stand to benefit. It’s still the same basic relationship, but the balance of information is different, and the AD’s role is by default a stronger one.

Ricardo Mendez Mattar

First Assistant Director

The Gardener, The Lost City, Bread and Roses

Vocabulary

above the line

base camp

below the line

boarding

call sheet

company move

crew call

dailies

daybreaks

day-out-of-days (DOOD)

first assistant director (1st AD)

first team

gaffe

make the day

marks

meat of the day

one-liner

production report

roll the carts

script day

second team

set background

set piece

setups

shooting schedule

special needs chart

stakebeds

standing set

swing set

turnaround

unit production

manager (UPM)

1. Rafferty, Terrence, “Uncommon Man,” DGA Quarterly, Summer 2010, pp. 35–36.