Case 26. Waste to Wealth—A Distant Dream?: Challenges in the Waste Disposal Supply Chain in Bangalore, India

† Loyola Institute for Business Administration, Chennai, India; [email protected]

‡ Loyola Institute for Business Administration, Chennai, India; [email protected]

Introduction

Bruhat Bangalore MahanagaraPalike (BBMP), a Karnataka state government authority, had recently set an ultimatum that waste segregation at the source will be compulsory for all Bangalore citizens beginning October 1, 2012. But the mandate received a very poor response. According to BBMP data, 3,281 tons of total waste was generated that day, out of which the segregated garbage accounted for 515 tons. The response was particularly poor in southern zones.

Palike publicized in different areas of Bangalore to meet the October 1, 2012 deadline. However, the efforts did not yield the desired result because Palike failed to provide enough awareness to citizens regarding the necessity of segregation of waste at the source. There were neither door-to-door campaigns to educate the masses nor any meetings with local residents’ welfare associations or voluntary organizations to create the necessary awareness. Monisha Ghoshbag, a Bangalore resident, noted:

But the pourakarmika who comes to my street does not understand the concept of segregated waste. I have started giving her only wet waste daily. Once the dry waste accumulates I give it separately. On days when I give her both, she does not understand and ends up mixing them in her “dabba” (box). My week’s efforts are wasted with her one minute’s act of waste mixing. She says no one instructs her like I do in that area and yet at the end of it all, she ignores what I say.

If a tepid response to the BBMP’s call is a concern on one hand, the failure of the existing landfill model is another. Even while the BBMP started experimenting with the new system, residents in villages on the city’s periphery were angry because they bore the brunt of tons of unprocessed waste being piled up in the nearby landfills for years.

During the month of August, the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) caved in to years of protests by residents of Mavallipura, where the city’s largest landfill is located, and was forced to shut down the solid waste management site.

If the reports from KSPCB are to be believed, instead of processing the waste, the site had simply been piling on mountains of garbage without processing. This action by KSPCB also meant that the loads that were sent to other landfills that were already running well over capacity doubled and tripled overnight. These issues are only indicative of a bigger problem the city is confronting.

Bangalore: City Statistics1

Bangalore is spread over an area of 800 sq. km. As of 2008, the population of Bangalore was 78 lakhs (7.8 million). There are 2.5 million houses and 350,000 commercial properties in the city. According to BBMP administrative classification, Bangalore has been divided into 8 zones and further into 198 wards. The estimated municipal solid waste generation during 2009 from all sources was 3000 tons/day.

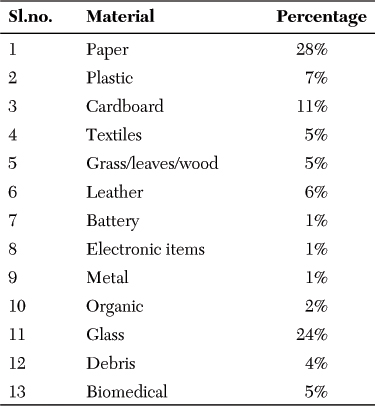

Out of this, the domestic waste per capita turns out to be 350 g/day. Households alone contribute 54%, with the next major contributor being commercial establishments. Table 26-1 displays a typical composition of municipal solid waste.

Table 26-1. Typical Physical Composition of Municipal Solid Waste

Collection of Waste

The system of waste collection is handled by both BBMP (35%) and contractors (65%). The contractors are selected after calling for a tender, which is basically a sealed bid lowest price auction mechanism. This process usually takes two to three months. There are about 4200 pourakarmikas (sweepers) from BBMP and 9500 pourakarmikas from contractors who perform the door-top-door collection and sweeping activities. There are some areas in Bangalore where this door-to-door collection activity is entrusted to women’s self-help groups (SHGs). The members of these SHGs live below the poverty line. Even the local residential welfare associations are involved in these collection and disposal activities.

It is generally accepted that quantification of solid waste is the single most important activity in proper waste disposal. However, BBMP does not have a mechanism with which the waste can be quantified in all of the zones.

Exhibit 26-1 displays a mapping of the waste collection supply chain.

Door-to-Door Collection

Door-to-door collection is the primary means of waste collection in Bangalore, followed by the community bin method. In the community bin method, waste is stored in large, concrete circular bins. There are a lot of concerns raised for the community bin storage. For instance, bin designs are standardized and in many places are not proportional to the amount of waste generated.

In door-to-door collection, pushcarts and auto tippers are used for collecting the waste from each household. There are approximately 10,000 pushcarts and 600 auto tippers available for the door-to-door collection. It should be observed that until September 30, 2012, the waste was collected in an unsegregated format.

Secondary Collection and Transportation

The waste collected by the BBMP and contractors is brought to a common aggregation point. Vehicles such as compactors, tipper lorries, dumper placers, and mechanical sweepers are used by both BBMP and contractors. At this point, many waste pickers collect solid materials, such as plastic, polythene bags, papers, card boards, and PET bottles from the dumped garbage. Waste pickers sell these materials to junk dealers to earn money. Some of the contract workers are also involved in this commercial activity. From here, the waste is transported to the decentralized processing plants, dry waste collection centers, and landfills.

Recycling

Waste pickers form part of larger network of waste recycling in the country. They carry out the valuable economic activity of collecting different kinds of solid waste from streets and dumping grounds, cleaning/sorting/segregating them into different materials, and selling these to junk dealers. Waste pickers collect all solid materials from municipal waste wherever it is available. They collect up to 10 to 15 kgs. of each material per day. Materials collected at the waste picker level are classified into different qualities or grades while moving up the recycling supply chain.

Most of the value-added activities such as segregation, breaking materials, and some cleaning are done by waste pickers. But they are the lowest-paid members of the chain. The working conditions of these waste pickers are appalling. They do not have sufficient protection and are sometimes exposed to hazardous waste. A study carried out in 2003 revealed that most of the rag pickers have some kind of a respiratory disease.

Subsequent to the primary step in the recycling process, materials are sorted into low-value, medium-value, and high-value material when they are bought by junk dealers and wholesalers, and prices also vary accordingly. Junk dealers add value to material by means of better storage, accumulation, and some sorting. Wholesalers add value to material by converting waste material into a form that can be used by recyclers. Sometimes the number of stages in the chain increases and hence the efficiency decreases. For example, a small junk dealer may sell all his material to a large junk dealer. In this case, the number of stages increases to five from four. With more intermediate stages, the total supply chain cost increases.

Materials such as cardboards are sold to factories in the nearby state, TamilNadu, which uses them for printing newspapers. Wholesalers normally deal with few materials such as paper and cardboard or plastic. Even metals are traded by wholesalers to industry.

In addition to composting methods, technologies such as anaerobic digesters and incineration are used as a means of disposal of organic waste. However, these methods have not taken off successfully. For instance, although composting is a popular method, it is not economically viable because of the required maintenance. Successful composting requires continuous feeding of the organic waste, and it has been difficult to sustain the feeding. Anaerobic digesters have appeared on a small scale, but there are not many large-scale digesters in all of India.

Landfilling

Prior to closing the Mavallipura site, BBMP, using a public-private-partnership model, had been operating four landfill waste disposal sites. Various technologies are used for processing waste at landfills such as vermi composting and biomethanization. Special mention has to be made of uncontrolled landfilling, because it is the most popular method of waste disposal in India. There are systematic ways in which waste could be dumped, but to save money these are not being followed at the dumping sites.

Role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

NGOs fill an important void in the waste management process. A variety of activities are carried out by NGOs that are instrumental in efficient functioning of the system:

• Public grievances are collected during the meetings organized by NGOs, and the complaints received are routed to the proper authorities for suitable action.

• They are involved in helping local authorities with the primary collection of waste.

• Training and awareness programs for waste pickers are conducted by NGOs.

• Some NGOs are also engaged in setting up and operating decentralized waste processing plants.

Conclusion

The waste management process is a lengthy and complex process that is the primary responsibility of BBMP and its associated contractors. This process is aided by waste pickers who form an important entity in the system. They not only collect waste, but they also perform the important activity of sorting and segregation before selling the materials. However, they are the lowest-paid and most-neglected entities in the process. The current system of waste management by BBMP has failed to efficiently implement and manage the entire process. BBMP and the contractors focus only on economic benefits and do not look at the social costs. Also, the recent move to adopt source segregation has faulted primarily because of failure on the part of BBMP to create necessary awareness in society. Such issues can only be addressed if one thinks beyond the economic benefits for the waste management operators.

2. What are the various roles of stakeholders in this waste recycle supply chain?

3. Can this supply chain be improved, and through this can all benefit?

4. How should waste pickers be integrated with the system, particularly if private corporations get involved?

5. How can NGOs help identify solutions to these problems?

6. What steps can BBMP take to improve the current system?