CHAPTER 7

Managing Project Costs

In this chapter, you will

• Plan for project cost management

• Estimate the project costs

• Administer the project budget

• Manage project cost control

• Work with earned value management

Money. Cash. Greenbacks. Dead presidents. It’s all the same thing when you get down to it: Projects require finances to get from start to completion, and it’s often the project manager’s job to estimate, control, and account for the finances a project demands. Projects consume the project budget during execution, when all of those project management plans we’ve discussed are put into action, and the project budget is monitored and controlled during, well, the monitoring and controlling processes.

What’s that you say? You don’t have any control over the monies your project requires? Management gives you a predetermined budget, and it’s up to you to make it all work out? Yikes! While this book centers on your Certified Associate in Project Management (CAPM) and Project Management Professional (PMP) examinations, that’s always one of the scariest things I hear. Or is it? If management’s decision is based on previous projects, business analysts’ research, or should-cost estimates from experts, then it’s not so scary. I’ll give you this much: A predetermined project budget is always a constraint, and it’s rarely fun for the project manager.

And what about those projects that don’t have any monies assigned to the project work? You know… the projects where the project scope is completed just by the project team’s work, and there really aren’t any materials or items to purchase. That’s okay— there are still costs associated with the project, because someone, somewhere, is paying for the project team’s time. Salaries can also be considered a project cost. After all, time is money.

VIDEO For a more detailed explanation, watch the Using Earned Value Management video now.

VIDEO For a more detailed explanation, watch the Using Earned Value Management video now.

Finally—and here’s the big whammy—it doesn’t really matter where your project monies come from, whether you actually control them, and the processes your organization uses to spend them. Your Project Management Institute (PMI) exam makes you understand all of the appropriate processes and procedures of how projects are estimated, budgeted, and then financially controlled. And that’s what we’ll discuss in this chapter.

You know by now, I’m assuming, that there are 47 project management processes. Guess how many of them center on cost? Four: planning cost management, cost estimating, cost budgeting, and cost controlling. Isn’t that reassuring? Your PMI exam will, no doubt, have questions on costs, but so much of the content of this chapter refers to your enterprise environmental factors. (Remember that term? It’s how your company does business.) Your cost management plan defines and outlines your organization’s and project’s procedures for cost management and control. I’ll not pass the buck anymore. Let’s go through this chapter like a wad of cash at an all-night flea market.

Planning for Project Cost Management

You need a plan just for project costs. You need a plan that will help you define what policies you and the project team have to adhere to in regard to costs, a plan that documents how you get to spend project money, and a plan for how cost management will happen throughout your entire project. Well, you’re in luck! This plan, a subsidiary plan of the project management plan, is the project cost management plan.

Like most of these subsidiary plans, you can use a template from past projects, your project management office, or your program manager to build the plan that’s specific to your project. Or, if you really have to, you can create a project cost management plan from scratch. It’s not much fun, but I’ll show you how to do it. You’ll also need to know the business of preparing this cost management plan for your PMI examination—you’ll certainly have some questions about what’s included in the plan and how you and the project team work together to build the plan and execute it throughout the project.

Preparing the Project Cost Management Plan

In order to prepare to complete the process of cost management planning, you’ll need four inputs:

• Project management plan

• Project charter

• Enterprise environmental factors

• Organizational process assets

Now don’t let the idea of the project management plan scare you. Remember that planning is an iterative activity. You’ll have some elements of the project management plan already completed when you start this cost management planning—and some parts of the project management plan won’t be completed yet. As more and more information becomes available, you can return to this cost management plan and adjust it as necessary. For example, you may not know the specific rules about how your company can purchase materials. You might need to go speak with your project sponsor, the purchasing department, or your program manager to confirm these rules and then you could return to the cost management plan and update the information accordingly.

You’ll also need the project management plan and its scope baseline to help the cost management planning. Recall that the scope baseline is the WBS, the WBS dictionary, and the project scope statement. The WBS will help you determine what resources you need to purchase, how estimating the expenses relate to the project’s deliverables, and the time accountability for nonexempt project team members such as contractors.

NOTE You’ll reference the project charter for just one reason: the summary budget. Remember, the project charter includes a summary budget for the project so you’ll use that amount as a foundation for project cost management.

NOTE You’ll reference the project charter for just one reason: the summary budget. Remember, the project charter includes a summary budget for the project so you’ll use that amount as a foundation for project cost management.

The actual creation of the cost management plan relies heavily on meetings. Nothing like some meetings about the project budget, right? You’ll need meetings specifically with your key stakeholders and subject matter experts. These people can help guide and direct you about the organization’s environment, tell you about similar projects they’ve worked on or sponsored, and help with the enterprise environmental factors and organizational processes you’ll have to adhere to in cost management.

These meetings will likely include some analytical techniques to analyze the anticipated cost of the project, the return on investment, and how the project should be funded. Self-funding means the organization pays for the project expenses from their cash flow. Funding with equity means the organization balances the project expenses with equity they have in their assets. Funding with debt means the company pays for the project through a line of credit or bank loan. There are pros and cons to each approach, and an analysis of the true cost of the project, the cost of the funding, and the risk associated with the project is examined as part of the decision.

NOTE The time value of money was covered in Chapter 4. Present value, future value, net present value, and the internal rate of return are all applicable here, too.

NOTE The time value of money was covered in Chapter 4. Present value, future value, net present value, and the internal rate of return are all applicable here, too.

Examining the Project Cost Management Plan

Once you’ve created the cost management plan, you have a clear direction on how you’ll estimate, budget, and manage the project costs. This plan defines, much like the schedule management plan, the level of accuracy defined for the project and the units of measurement. For example, you might round financial figures to the nearest $100 or keep track of costs to the exact penny. Your unit of measurement isn’t just dollars, yen, or euros, but also things like a workday, hours, or even weeks for labor. Keep in mind, some organizations do not include the cost of labor in the project, while other companies do.

If you’re using control accounts in your WBS, you’ll reference those control accounts in your cost management plan. Recall that a control account is like a “mini-budget” for a chunk of the WBS. For example, a house project may have a control account for the basement, the first floor, the second floor. Or you could get more specific and have a control account for the kitchen in the house project. Whatever approach you’re using, you’d reference that information in the cost management plan—the PMBOK Guide calls this an organizational procedure link.

Just as you defined control thresholds for your schedule, you’ll do the same for your project costs. Control thresholds, as a reminder, are the limits of variance before a corrective action is needed in the project. For example, a project may have a control threshold of 10 percent off budget before a predefined action is taken. Or the control threshold could be any cost variance greater than $5,000 requires project management action. The action could be a corrective action, but also may include an exceptions report or variance report to management.

Determining the Project Costs

One of the first questions a project manager is likely to be asked when a project is launched is, “How much will this cost to finish?” That question can only be answered through progressive elaboration. To answer the question, the project manager, or the project estimator as the case may be, first needs to examine the costs of the resources needed to complete each activity in the project. Resources, of course, are people, but also things: equipment, material, training, even pizza if the project demands it.

On top of the cost of the resources, there’s also all the variances that must be considered: project risks, fluctuations in the cost of materials, the appropriate human resources for each activity, and oddball elements like shipping, insurance, inflation, and monies for testing and evaluations.

Estimates, as Figure 7-1 depicts, usually come in one of three flavors through a series of refinements. As more details are acquired as the project progresses, the estimates are refined. Industry guidelines and organizational policies may define how the estimates are refined.

• Rough order of magnitude (ROM) This estimate is rough and is used during the initiating processes and in top-down estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –25 percent to +75 percent.

• Budget estimate This estimate is also somewhat broad and is used early in the planning processes and also in top-down estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –10 percent to +25 percent.

• Definitive estimate This estimate type is one of the most accurate. It’s used late in the planning processes and is associated with bottom-up estimating. You need the work breakdown structure (WBS) in order to create the definitive estimate. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –5 percent to +10 percent.

EXAM TIP The range of variance percentages are pretty typical of these estimate types, but there’s no steadfast rule that the estimates must follow these ranges. Your organization may use entirely different ranges of variance for each estimate type.

EXAM TIP The range of variance percentages are pretty typical of these estimate types, but there’s no steadfast rule that the estimates must follow these ranges. Your organization may use entirely different ranges of variance for each estimate type.

While project managers typically think of project estimates as some unit of measure such as dollars, euros, or yen, it’s possible and often feasible to estimate project costs based on labor. Consider the number of hours the project team must work on creating a new piece of software. You could even estimate based on the number of full-time employees assigned to the project for a given duration.

EXAM TIP If your organization doesn’t use a cost estimator, the project manager and the project team work together to estimate the project costs.

EXAM TIP If your organization doesn’t use a cost estimator, the project manager and the project team work together to estimate the project costs.

Estimating the Project Costs

Assuming that the project manager and the project team are working together to create the cost estimates, there are many inputs to the cost-estimating process. For your PMI exam, it would behoove you to be familiar with these inputs because these are often the supporting details for the cost estimate the project management team creates. Let’s have a look, shall we?

Referencing the Cost Management Plan

You’ve created the cost management plan, so might as well use it. The plan is used as an input for cost estimating because it defines the level of detail needed in the cost estimates you’re creating. You’ll follow the cost management plan’s requirements for cost estimating, rounding, and adherence to enterprise environmental factors.

Including the Human Resource Plan

If your organization includes an accounting of the cost of labor, you’ll obviously need this project management subsidiary plan. The human resource plan, which is covered in Chapter 9, defines the cost of labor, contracted labor rates, and the budget allotted for rewards and recognition for the project. You’ll need this information to predict what the costs of the project will be.

Using the Project Scope Baseline

You’ll need the project scope baseline often enough. First, the project scope statement is an input to the cost-estimating process. What a surprise! The project scope statement is needed because it defines the business case for the project, the project justifications, and the project requirements—all things that’ll cost cash to achieve. The project scope statement can help the project manager and the stakeholders negotiate the funding for the project based on what’s already been agreed upon. In other words, the size of the budget has to be in proportion to the demands of the project scope statement.

While the project scope statement defines constraints, it also defines assumptions. In Chapter 11, which discusses risk management, we’ll discuss how assumptions can become risks. Basically, if the assumptions in the project scope statement prove false, the project manager needs to assess what the financial impact may be.

Consider all of the elements in the project scope statement that can contribute to the project cost estimate:

• Contractual agreements

• Insurance

• Safety and health issues

• Environment expenses

• Security concerns

• Cost of intellectual rights

• Licenses and permits

Last, and perhaps one of the more important elements in the project scope statement, is the requirements for acceptance. The cost estimate must reflect the monies needed to attain the project customer’s expectations. If the monies are not available to create all of the elements within the project scope, then either the project scope must be trimmed to match the monies that are available, or more cash needs to be dumped into the project.

Next, you’ll need the second part of the scope baseline: the work breakdown structure (WBS). The WBS is needed to create a cost estimate, especially the definitive estimate, because it clearly defines all of the deliverables the project will create. Each of the work packages in the WBS will cost something in the way of materials, time, or often both. You’ll see the WBS as a common theme in this chapter, because the monies you spend on a project are for the things you’ve promised in the WBS.

Finally, you’ll need the WBS’s pal, the WBS dictionary, because it includes all of the details and the associated work for each deliverable in the WBS. As a general rule, whenever you have the WBS involved, the WBS dictionary tags along.

Examining the Project Schedule

The availability of resources, when the resources are to do the work, when capital expenses are to happen, and so on are needed for cost estimating. The schedule management plan can also consider contracts with collective bargaining agreements (unions) and their timelines, the seasonal cost of labor and materials, and any other timings that may affect the overall cost estimate. The project schedule can help you determine not only when resources are needed, but when you’ll have to pay for those resources.

Referencing the Risk Register

A risk is an uncertain event that may cost the project time, money, or both. The risk register is a central repository of the project risks and the associated status of each risk event. Some risks the project team can buy their way out of, while other risks will cost the project if they come true. We’ll discuss risks in detail in Chapter 11, but for now, know that the risk register is needed because the cost of the risk exposure helps the project management team create an accurate cost estimate.

EXAM TIP Risks may not always cost monies directly, but could affect the project schedule. Keep in mind, however, that this could in turn cause a rise in project costs because of vendor commitment, penalties for lateness, and added expenses for extra labor.

EXAM TIP Risks may not always cost monies directly, but could affect the project schedule. Keep in mind, however, that this could in turn cause a rise in project costs because of vendor commitment, penalties for lateness, and added expenses for extra labor.

Relying on Enterprise Environmental Factors

Every time I have to say or write “enterprise environmental factors,” I cringe. It’s just a fancypants way of saying how your organization runs its shop. Within any organization, “factors” affect the cost-estimating process. Surprise, surprise, there are two for your exam:

• Marketplace conditions When you have to buy materials and other resources, the marketplace dictates the price, what’s available, and from whom you will purchase them. We’ll talk all about procurement in Chapter 12, but for now, there are three conditions that can affect the price of anything your project needs to purchase:

• Sole source When there’s only one vendor that can provide what your project needs to purchase. Examples include a specific consultant, a specialized service, or a unique type of material.

• Single source When there are many vendors that can provide what your project needs to purchase, but you prefer to work with a specific vendor. They are your favorite.

• Oligopoly This is a market condition in which the market is so tight that the actions of one vendor affect the actions of all the others. Can you think of any? How about the airline industry, the oil industry, or even training centers and consultants?

• Commercial databases One of my first consulting gigs was for a large commercial printer. We used a database—based on the type of materials the job was to be printed on, the number of inks and varnish we wanted to use, and the printing press we’d use—to predict how much the job would cost. That’s a commercial database. Another accessible example is any price list your vendors may provide so that you can estimate the costs accurately.

EXAM TIP Here’s a goofy way to remember all the market conditions for your PMI exam. For a sole source, think of James Brown, the Godfather of Soul. There’s only one James Brown, just as there’s only one vendor. For a single source, think of all the single people in the world and how you only want to date your sweetie instead of all the others. With a single source, you consider all the different available vendors, but you have your favorite. And for oligopoly? It sounds like “oil” which we know is a classic example of an oligopoly market. Hey, I warned you these were goofy!

EXAM TIP Here’s a goofy way to remember all the market conditions for your PMI exam. For a sole source, think of James Brown, the Godfather of Soul. There’s only one James Brown, just as there’s only one vendor. For a single source, think of all the single people in the world and how you only want to date your sweetie instead of all the others. With a single source, you consider all the different available vendors, but you have your favorite. And for oligopoly? It sounds like “oil” which we know is a classic example of an oligopoly market. Hey, I warned you these were goofy!

Using Organizational Process Assets

Here’s another term that makes my teeth hurt: organizational process assets. These are just things your organization has learned, created, or purchased that can help the project management team manage a project better. When it comes to cost estimating, an organization can use many assets:

• Cost-estimating policies An organization can, and often will, create a policy on how the project manager or the cost estimator is to create the project cost estimate. It’s just their rule. Got any of those where you work?

• Cost-estimating templates In case you’ve not picked up on this yet, the PMI and the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) love templates. Templates in project management don’t usually mean a shell in the way that Microsoft Word thinks of templates. We’re talking about using past similar projects to serve as a template for the current project.

• Historical information Beyond the specific costs of previous projects, historical information is just about anything that came before this project that can help the project manager and the project team create an accurate cost estimate.

• Project files Project archives and files from past projects can help with the cost-estimating process. Specifically, the project manager is after the performance of past similar projects in areas of cost control, the cost of risks, and quality issues that could affect costs.

• Project team knowledge Your project team usually consists of the experts closest to the project work and can be a valuable input to the project cost-estimating process. Be forewarned—for the real world and your PMI exam, project team recollections are great, but aren’t the most reliable input. In other words, Marty’s war stories about how Project XYZ was $14 billion over budget don’t compare with historical information that says Project XYZ was $14 over budget.

• Lessons learned It’s always good to rely on lessons learned as an input during planning. After all, it’s better to learn from someone else’s mistakes.

EXAM TIP Sometimes an organization has two projects, or opportunities, and they can only choose one of the projects to complete. For example, Project A is worth $75,000, and Project B is worth $250,000. The organization will likely choose Project B because it is worth more, and let Project A go because it is worth considerably less. Opportunity cost is a term to describe the total amount of the project that was let go in lieu of the project that was selected. In this instance, the opportunity cost is $75,000: the worth of Project A.

EXAM TIP Sometimes an organization has two projects, or opportunities, and they can only choose one of the projects to complete. For example, Project A is worth $75,000, and Project B is worth $250,000. The organization will likely choose Project B because it is worth more, and let Project A go because it is worth considerably less. Opportunity cost is a term to describe the total amount of the project that was let go in lieu of the project that was selected. In this instance, the opportunity cost is $75,000: the worth of Project A.

Creating the Cost Estimate

All of the cost inputs are needed so that the project cost estimator, likely the project management team, can create a reliable cost estimate. The estimates you’ll want to know for the CAPM and PMP exam, and for your career, reflect the accuracy of the information the estimate is based upon. The more accurate the information, the better the cost estimate will be. Basically, all cost estimates move through progressive elaboration: as more details become available, the more accurate the cost estimate is likely to be. Let’s examine the most common approaches to determining how much a project is likely to cost.

Using Analogous Estimating

Analogous estimating relies on historical information to predict the cost of the current project. It is also known as top-down estimating and is the least reliable of all the cost-estimating approaches. The process of analogous estimating uses the actual cost of a historical project as a basis for the current project. The cost of the historical project is applied to the cost of the current project, taking into account the scope and size of the current project, as well as other known variables.

Analogous estimating is considered a form of expert judgment. This estimating approach takes less time to complete than other estimating models, but is also less accurate. This top-down approach is good for fast estimates to get a general idea of what the project may cost. The trouble, or risk, with using an analogous estimate, however, is that the historical information that estimate is based upon must be accurate. For example, if I were to create a cost estimate for Project NBG based on a similar project Nancy did two years ago, I’d be assuming that Nancy kept accurate records and that her historical information is accurate. If it isn’t, then my project costs are not going to be accurate, and I’m going to be really mad at Nancy.

Determining the Cost of Resources

One of the project management plans needed for cost estimating is the human resource management plan, which defines all of the attributes of the project staff, including the personnel rates. Armed with this plan and a determination of what resources are needed to complete the project, the project manager can extrapolate what the cost of the human resource element of the project will likely be.

Resources include more than just the people doing the project work. The cost estimate must also reflect all of the equipment and materials that will be utilized to complete the work. In addition, the project manager must identify the quantity of the needed resources and when the resources are needed for the project. The identification of the resources, the needed quantity, and the schedule of the resources are directly linked to the expected cost of the project work.

There are four variations on project expenses to consider:

• Direct costs These costs are attributed directly to the project work and cannot be shared among projects (airfare, hotels, long-distance phone charges, and so on).

• Indirect costs These costs are representative of more than one project (utilities for the performing organization, access to a training room, project management software license, and so on).

• Variable costs These costs vary depending on the conditions applied in the project (the number of meeting participants, the supply and demand of materials, and so on).

• Fixed costs These costs remain constant throughout the life cycle of the project (the cost of a piece of rented equipment for the project, the cost of a consultant brought onto the project, and so on).

And yes, you can mix and match these terms. For example, you could have a variable cost based on shipping expenses that is also a direct cost for your project. Don’t get too hung up on these cost types—just be topically familiar with them for your PMI exam.

Using Bottom-Up Estimating

Bottom-up estimating starts from zero, accounts for each component of the WBS, and arrives at a sum for the project. It is completed with the project team and can be one of the most time-consuming methods used to predict project costs. While this method is more expensive because of the time invested to create the estimate, it is also one of the most accurate. A fringe benefit of completing a bottom-up estimate is that the project team may buy into the project work since they see the value of each cost within the project.

Using Parametric Estimating

“That’ll be $465 per metric ton.”

“You can buy our software for $765 per license.”

“How about $125 per network drop?”

These are all examples of parameters that can be integrated into a parametric estimate. Parametric estimating uses a mathematical model based on known parameters to predict the cost of a project. The parameters in the model can vary based on the type of work being completed and can be measured by cost per cubic yard, cost per unit, and so on. A complex parameter can be cost per unit, with adjustment factors based on the conditions of the project. The adjustment factors may have several modifying factors, depending on additional conditions.

There are two types of parametric estimating:

• Regression analysis This is a statistical approach that predicts future values based on historical values. Regression analysis creates quantitative predictions based on variables within one value to predict variables in another. This form of estimating relies solely on pure statistical math to reveal relationships between variables and to predict future values.

• Learning curve This approach is simple: The cost per unit decreases the more units workers complete, because workers learn as they complete the required work (see Figure 7-2). The more an individual completes an activity, the easier it is to complete. The estimate is considered parametric, since the formula is based on repetitive activities, such as wiring telephone jacks, painting hotel rooms, or other activities that are completed over and over within a project.

EXAM TIP Don’t worry too much about regression analysis for the exam. The learning curve is the topic you’re more likely to have questions on.

EXAM TIP Don’t worry too much about regression analysis for the exam. The learning curve is the topic you’re more likely to have questions on.

Using Good Old Project Management Software

Who’s creating estimates with their abacus? Most organizations rely on software to help the project management team create an accurate cost estimate. While the CAPM and PMP examinations are vendor neutral, a general knowledge of how computer software can assist the project manager is needed. Several different computer programs are available that can streamline project work estimates and increase their accuracy. These tools can include project management software, spreadsheet programs, and simulations.

Examining the Vendor Bids

Sometimes it’s just more cost-effective (and easier) to hire someone else to do the work. Other times, the project manager has no choice, because the needed skill set doesn’t exist within the organization. In either condition, the vendors’ bids need to be analyzed to determine which vendor should be selected based on their ability to satisfy the project scope, the expected quality, and the cost of their services. We’ll talk all about procurement in Chapter 12.

Implementing Three-Point Estimating

A three-point estimate uses three factors to predict a cost: pessimistic, optimistic, and most likely. A three-point estimate can use a simple average of the three factors or it can use a weighted factor for the most likely factor. For example, a project manager predicts the pessimistic cost to be $5,600, the most likely cost to be $4,800, and the optimistic cost to be $3,500. With the simple average, you’d just add up the three amounts and divide by three for a value of $4,633.

With the weighted average, you’ll consider all of the same costs, but the most likely amount is multiplied by four, and then you’ll divide the sum of the three values by six. Here’s what this looks like with the same costs ($5,600 + (4 × 4,800) + 3,500)/6 = $4,716. So in this instance the weight average leans more toward the most likely amount than does the simple average.

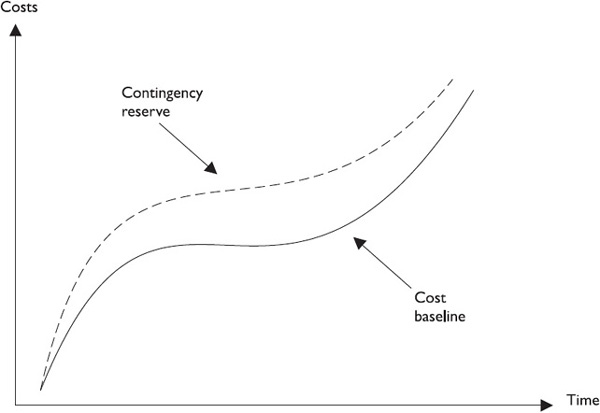

Creating a Reserve Analysis

Do you think it’ll snow next December in Michigan? I do, too. But do we know on what exact date? That’s a quick and easy example of a known unknown. You know that something is likely to occur, but you just don’t know when or to what degree. Projects are full of known unknowns, and the most common unknown deals with costs. Based on experience, the nature of the work, or fear, you suspect that some activities in your project will cost more than expected—that’s a known unknown.

Rather than combating known unknowns by padding costs with extra monies, the PMBOK suggests that we create “contingency allowances” to account for these overruns in costs. The contingency allowances are used at the project manager’s discretion to counteract cost overruns for scheduled activities. In Chapter 6, we discussed the concept of management reserve for time overruns. This is a related concept when it comes to the cost reserve for projects. This reserve is sometimes called a contingency reserve and is traditionally set aside for cost overruns due to risks that have affected the project cost baseline. Contingency reserves can be managed in a number of ways. The most common is to set aside an allotment of funds for the identified risks within the project. Another approach is to create a slush fund for the entire project for identified risks and known unknowns. The final approach is an allotment of funds for categories of components based on the WBS and the project schedule.

Considering the Cost of Quality

The cost of quality, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 8, defines the monies the project must spend to reach the expected level of quality within a project. For example, if your project will use a new material that no one on the project team has ever worked with, the project team will likely need training so they can use it. The training, as you can guess, costs something. That’s an example of the cost of quality.

On the other side of the coin (cost pun intended, thank you), there’s the cost of poor quality, sometimes called the cost of nonconformance to quality. These are the costs your project will pay if you don’t adhere to quality the first time. In our example with the project team and the new materials, a failure to train the team on the new materials will mean that the team will likely not install the materials properly, take longer to use the materials, and may even waste materials. All of these negative conditions cost the project in time, money, team frustration, and even loss of sales.

Examining the Cost Estimate

Once all of the inputs have been evaluated and the estimate creation process is completed, you get the cost estimate. The estimate is the likely cost of the project—it’s not a guarantee, so there is usually a modifier—sometimes called an acceptable range of variance. That’s the plus/minus qualifier on the estimate—for example, $450,000 + $25,000 to –$13,000, based on whatever conditions are attached to the estimate. The cost estimate should, at the minimum, include the likely costs for all of the following:

• Labor

• Materials

• Equipment

• Services

• Facilities

• Information technology

• Special categories, such as inflation and contingency reserve

It’s possible for a project to have other cost categories, such as consultants, outsourced solutions, and so on, but the preceding list is the most common. Consider this list when studying to pass your exam.

Along with the cost estimate, the project management team includes the basis of the estimate. These are all the supporting details of how the estimate was created and why the confidence in the estimate exists at the level it does. Supporting details typically include all of the following:

• Description of the work to be completed in consideration of the cost estimate

• Explanation of how the estimate was created

• What assumptions were used during the estimate creation

• The constraints that the project management team had to consider when creating the cost estimate

A project’s cost estimate may lead to some unpleasant news in the shape of change requests. I say “unpleasant,” because changes are rarely enjoyable. Changes can affect the scope in two primary ways when it comes to cost:

We don’t have enough funds to match the cost estimate, so we’ll need to trim the scope.

We have more than enough funds to match the cost estimate, so let’s add some stuff into the scope.

All change requests must be documented and fed through the integrated change control system, as discussed in Chapter 4. What the project manager wants to be leery of is gold plating. Gold plating is when the project manager, the project sponsor, or even a stakeholder adds in project extras to consume the entire project budget. It’s essentially adding unneeded features to the product in order to use up all the funds allocated to the project. While this often happens in the final stages of a project, it can begin right here during the project cost estimating. Gold plating delivers more than what’s needed and can create new risks and work, and can contribute to a decline in team morale.

If changes are approved, then integrated change control is enacted, the project scope is updated, the WBS and WBS dictionary are updated, and so on, through all of the project management plans as needed. The cost management plan needs to be updated as well to reflect the costs of the changes and their impact on the project cost estimate.

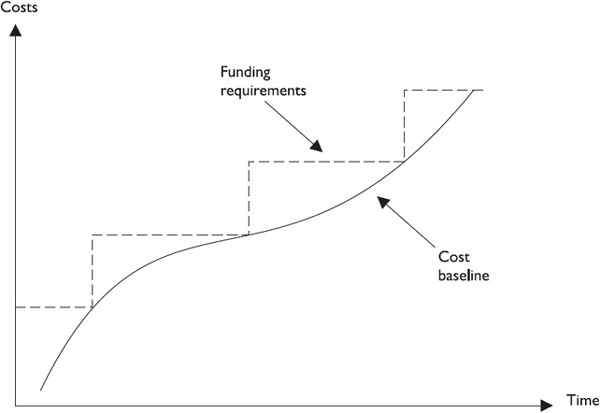

Budgeting the Project

Now that the project estimate has been created, it’s time to create the official cost budget. Cost budgeting is really cost aggregation, which means the project manager will be assigning specific dollar amounts for each of the scheduled activities or, more likely, for each of the work packages in the WBS. The aggregation of the work package cost equates to the summary budget for the entire project. This process creates the cost baseline, as Figure 7-3 shows.

Cost budgeting and cost estimates may go hand in hand, but estimating is completed before a budget is created—or assigned. Cost budgeting applies the cost estimates over time. This results in a time-phased estimate for cost, which allows an organization to predict cash flow, to project return on investment, and to perform forecasting. The difference between cost estimates and cost budgeting is that cost estimates show costs by category, whereas a cost budget shows costs across time.

Creating the Project Budget

Good news! Many of the tools and techniques used to create the project cost estimates are also used to create the project budget. The following is a quick listing of the tools you can expect to see on the CAPM and PMP exams:

• Cost aggregation Costs are parallel to each WBS work package. The costs of each work package are aggregated to their corresponding control accounts. Each control account is then aggregated to the sum of the project costs.

• Reserve analysis Cost reserves are for unknown unknowns within a project. The contingency reserve is not part of the project cost baseline, but is included as part of the project budget.

• Historical relationships This is kind of a weird term. Historical relationships in cost estimating describe the history of costs in a given industry. For example, construction uses a cost per square foot, while software development can charge a fee per hour depending on the type of resource being used. This approach uses a parametric model to extrapolate what costs will be for a project (for example, cost per hour and cost per unit). It can include variables and the additional percentage of fee points based on conditions.

• Funding limit reconciliation Organizations only have so much cash to allot to projects—and no, you can’t have all the monies right now. Funding limit reconciliation is an organization’s approach to managing cash flow against the project deliverables based on a schedule, milestone accomplishment, or data constraints. This helps an organization plan when monies will be devoted to a project rather than using all of the funds available at the start of a project. In other words, the monies for a project budget will become available based on dates and/or deliverables. If the project doesn’t hit predetermined dates and products that were set as milestones, the likelihood of additional funding becomes questionable.

Examining the Project Budget

As with most parts of the PMBOK, you don’t get just one output after completing a process, you get several. Creating the project budget is no different because there are three outputs to know for the PMI examination: cost baseline, project funding requirements, and project documents. The following sections look at these in detail.

Working with the Cost Baseline

The cost baseline, shown in Figure 7-3, is actually a time-lapse exposure of when the project monies are to be spent in relation to cumulative values of the work completed in the project. Most baselines are shown as an S-curve, where the project begins in the left and works its way to the upper-right corner. When the project begins, it’s not worth much and usually not much has been spent. As the project moves toward completion, the monies for labor, materials, and other resources are consumed in relation to the work. In other words, the monies spent on the project over time will equate to the work the project is completing.

Some projects, especially projects that are of high priority or are large, may have multiple cost baselines to track cost of labor, cost of materials, even the cost of internal resources compared with external resources. This is all fine and dandy, as long as the values in each of the baselines are maintained and consistent. It wouldn’t do a project manager much good if the cost baseline for materials was updated regularly and the cost baseline for labor was politely ignored.

EXAM TIP Monies that have already been spent on a project are considered sunk into the project. These funds are called sunk costs—they’re gone.

EXAM TIP Monies that have already been spent on a project are considered sunk into the project. These funds are called sunk costs—they’re gone.

Determining the Project Funding Requirements

Projects demand a budget, but when the monies in the project are made available depends on the organization, the size of the project, and just plain old common sense. For example, if you were building a skyscraper that costs $850 million, you wouldn’t need all of the funds on the first day of the project, but you would forecast when those monies would be needed. That’s cash-flow forecasting.

The funding of the project, based on the cost baseline and the expected project schedule, may happen incrementally or may be based on conditions within the project. Typically, the funding requirements have been incorporated into the cost baseline. The release of funds is treated like a step function, which is what it is. Each step of the project funding allows the project to move on to the next milestone, deliverable, or whatever step of the project the project manager and the stakeholders have agreed to.

The project funding requirements also account for the management contingency reserve amounts. This is a pool of funds for cost overruns. Typically, the management contingency reserve is allotted to the project in each step, though some organizations may elect to only disburse contingency funds on an as-needed basis—that’s just part of organizational process assets.

To be crystal clear, the cost baseline is what the project should cost in an ideal, perfect world. The management contingency reserve is the “filler” between the cost baseline and the maximum funding. In most cases, the management contingency reserve bridges the gap between the project cost baseline and the maximum funding to complete the project. Figure 7-4 demonstrates the management contingency reserve at project completion.

The Usual Suspects

There are three more outputs of the cost-budgeting process. The outputs are:

• Cost baseline The cost baseline is the budget of the project—usually in ratio to when the funds are needed and how far along the project has progressed. In other words, in larger projects you don’t get all of the project budgeting at the start, but rather the monies are spent throughout the project. This is where you might see an S-curve of how much the project is predicted to spend in relation to the progress the project is to make. Ideally, you’ll run out of money right when the project reaches its conclusion.

• Project funding requirements Part of the project’s budget is a prediction of when you’ll need the money: capital expenses, monthly labor burn rates, contractual obligations, and project liabilities. You will need to consider the total budget requirements as part of the funding requirements. This includes the cost baseline and any management reserves for risk events.

• Project document updates You may need to update the risk register, cost estimates, and delete project schedule.

Controlling Project Costs

Once a project has been funded, it’s up to the project manager and the project team to work effectively and efficiently to control costs. This means doing the work right the first time. It also means, and this is tricky, avoiding scope creep and undocumented changes, as well as getting rid of any non-value-added activities. Basically, if the project team is adding components or features that aren’t called for in the project, they’re wasting time and money.

Cost control focuses on controlling the ability of costs to change and on how the project management team may allow or prevent cost changes from happening. When a change does occur, the project manager must document the change and the reason why it occurred and, if necessary, create a variance report. Cost control is concerned with understanding why the cost variances, both good and bad, have occurred. The “why” behind the variances allows the project manager to make appropriate decisions on future project actions.

EXAM TIP Variance reports are sometimes called exception reports.

EXAM TIP Variance reports are sometimes called exception reports.

Ignoring the project cost variances may cause the project to suffer from budget shortages, additional risks, or scheduling problems. When cost variances happen, they must be examined, recorded, and investigated. Cost control allows the project manager to confront the problem, find a solution, and then act accordingly. Specifically, cost control focuses on:

• Controlling causes of change to ensure that the changes are actually needed

• Controlling and documenting changes to the cost baseline as they happen

• Controlling changes in the project and their influence on cost

• Performing cost monitoring to recognize and understand cost variances

• Recording appropriate cost changes in the cost baseline

• Preventing unauthorized changes to the cost baseline

• Communicating the cost changes to the proper stakeholders

• Working to bring and maintain costs within an acceptable range

Managing the Project Costs

Controlling the project costs is more than a philosophy—it’s the project manager working with the project team, the stakeholders, and often management to ensure that costs don’t creep into the project, and then managing the cost increases as they happen. To implement cost control, the project manager must rely on several documents and processes:

• Cost baseline You know this one already. The cost baseline is the expected cost the project will incur and when those expenses will happen. This time-phased budget reflects the amount that will be spent throughout the project. Recall that the cost baseline is a tool used to measure project performance.

• Project funding requirements The funds for a project are not allotted all at once, but stair-stepped in alignment with project deliverables. Thus, as the project moves toward completion, additional funding is allotted. This allows for cash-flow forecasting. In other words, an organization doesn’t have to have the project’s entire budget allotted at the start of the project. It can predict, based on expected income and predicted expenses, that the budget will be available in incremental steps.

• Performance reports These reports focus on project cost performance, project scope, and planned performance versus actual performance. The reports may vary according to stakeholder needs. We’ll discuss performance reporting in detail in Chapter 10 and everyone’s favorite, earned value management, in just one moment.

• Change requests When a change to the project scope is requested, an analysis of the associated costs to complete the proposed change is required. In some instances, such as when removing a portion of the project deliverable, a change request may reduce the project cost. (I know, that’s wishful thinking. But in the PMI’s world, it’s possible.)

• Cost management plan The cost management plan dictates how cost variances will be managed. A variance is a difference between what was expected and what was experienced. In some instances, the management contingency reserve allowance can “cover” the cost overruns. In other instances, depending on the reason why the overrun occurred, the funding may have to come from the project customer. Consider a customer who wanted the walls painted green, and after the work was completed, changed his mind and wanted the walls orange. This cost overrun is due only to a change request and not to a defect.

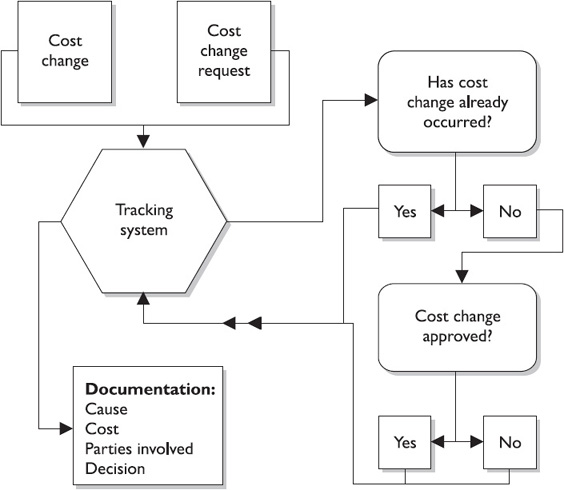

Creating a Cost Change Control System

Way, way back in Chapter 5, I discussed the scope change control system. Whenever some joker wants to add something to the project scope, or even take something out of our project scope, the scope change control system is engaged. Similarly, the cost change control system examines any changes associated with scope changes, the costs of materials, and the cost of any other resources you can imagine.

When a cost change enters the system, there is appropriate paperwork, a tracking system, and procedures the project manager must follow to obtain approval on the proposed change. Figure 7-5 demonstrates a typical work flow for cost change approval. If a change gets approved, the cost baseline is updated to reflect the approved changes. If a request gets denied, the denial must be documented for future potential reference. You don’t want a stakeholder wondering at the end of the project why his or her change wasn’t incorporated into the project scope without having some documentation as to why.

EXAM TIP There are four specific change control systems in project management: the scope change control system, the schedule change control system, the cost change control system, and the contract change control system.

EXAM TIP There are four specific change control systems in project management: the scope change control system, the schedule change control system, the cost change control system, and the contract change control system.

Using Earned Value Management

When I teach a PMP Boot Camp, attendees snap to attention when it comes to earned value management and their exam. This topic is foreign to many folks, and they understandably want an in-depth explanation of this suite of mysterious formulas. Maybe you find yourself in that same position, so here’s some good news: It’s not that big a deal. Relax—you can memorize these formulas, answer the exam questions correctly, and worry about tougher exam topics. I’ll show you how.

First, earned value management (EVM) is the process of measuring the performance of project work against what was planned to identify variances, opportunities to improve the project, or just to check the project’s health. EVM can help predict future variances and the final costs at completion. It is a system of mathematical formulas that compares work performed against work planned, and measures the actual cost of the work your project has performed. EVM is an important part of cost control since it allows a project manager to predict future variances from the expenses to date within the project.

Learning the Fundamentals

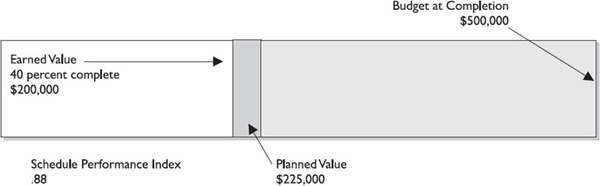

EVM, in regard to cost management, is concerned with the relationships among three formulas that reflect project performance. Figure 7-6 demonstrates the connection between the following EVM values:

• Planned value (PV) Planned value is the work scheduled and the budget authorized to accomplish that work. For example, if a project has a budget of $500,000 and month 6 represents 50 percent of the project work, the PV for that month is $250,000.

• Earned value (EV) Earned value is the physical work completed to date and the authorized budget for that work. For example, if your project has a budget of $500,000 and the work completed to date represents 45 percent of the entire project work, its earned value is $225,000. You can find EV by multiplying the percent complete times the project budget at completion (BAC).

• Actual cost (AC) Actual cost is the actual amount of monies the project has required to date. In your project, your BAC, for example, is $500,000, and your earned value is $225,000. As it turns out, your project team had some waste, and you spent $232,000 in actual monies to reach the 45-percent-complete milestone. Your actual cost is $232,000.

That’s the fundamentals of earned value management. All of our remaining formulas center on these simple formulas. Just remember that earned value is always the percent of work complete times the given budget at completion. On your PMI exam, you’ll always be provided with the actual costs, which are the monies that have already been spent on the project. You’ll have to do some math to find the planned value, which is the value your project should have by a given time. The formula for planned value is the percentage of project completion based on how complete the project should be at a given time. For example, let’s say you’re supposed to be 80 percent complete by December 15. If your budget is $100,000, in this instance your planned value is $80,000.

Finding the Project Variances

Out in the real world, I’m sure your projects are never late and never over budget (haha—pretty funny, right?). For your exam you’ll need to be able to find the cost and schedule variances for your project. I’ll stay with the same $500,000 budget I’ve been working with in the previous examples and as demonstrated in Figure 7-7. Finding the variances helps the project manager and management determine a project’s health, set goals for project improvement, and benchmark projects against each other based on the identified variances.

Finding the Cost Variance

Let’s say your project has a BAC of $500,000 and you’re 40 percent complete. You have spent, however, $234,000 in real monies. To find the cost variance, we’ll find the earned value, which is 40 percent of the $500,000 budget. As Figure 7-7 shows, this is $200,000. In this example, you spent $234,000 in actual costs. The formula for finding the cost variance is earned value minus actual costs. In this instance, the cost variance is –$34,000.

This means you’ve spent $34,000 dollars more than what the work you’ve done is worth. Of course, the $34,000 is in relation to the size of the project. On this project, that’s a sizeable flaw, but on a billion-dollar project, $34,000 may not mean too much. On either project, a $34,000 cost variance would likely spur a cost variance report (sometimes called an exceptions report).

Finding the Schedule Variance

Can you guess how the schedule variance works? It’s basically the same as cost variance, only this time, we’re concerned with planned value instead of actual costs. Let’s say your project with the $500,000 budget is supposed to be 45 percent complete by today, but we know that you’re only 40 percent complete. We’ve already found the earned value as $200,000 for the planned value.

Recall that planned value, where you’re supposed to be and what you’re supposed to be worth, is planned completion times the BAC. In this example, it’s 45 percent of the $500,000 BAC, which is $225,000. Uh-oh! You’re behind schedule. The schedule variance formula, as Figure 7-8 demonstrates, is earned value minus the planned value. In this example, the schedule variance is $25,000.

Finding the Indexes

In mathematical terms, an index is an expression showing a ratio—and that’s what we’re doing with these indexes. Basically, an index in earned value management shows the health of the project’s time and cost. The index, or ratio, is measured against one: the closer to one the index is, the better the project is performing. As a rule, you definitely don’t want to be less than one because that’s a poorly performing project. And, believe it or not, you don’t want to be too far from one in your index, as this shows estimates that were bloated or way, way too pessimistic. Really.

Finding the Cost Performance Index

The cost performance index (CPI) measures the project based on its financial performance. It’s an easy formula: earned value divided by actual costs, as Figure 7-9 demonstrates. Your project, in this example, has a budget of $500,000 and you’re 40 percent complete with the project work. This is an earned value of how much? Yep. It’s 40 percent of the $500,000, for an earned value of $200,000.

Your actual costs for this project to date (the cumulative costs) total $234,000. Your PMI exam will always tell you your actual costs for each exam question. Let’s finish the formula. To find the CPI, we divide the earned value by the actual costs, or $200,000 divided by $234,000. The CPI for this project is .85, which means that we’re 85 percent on track financially, not too healthy for any project, regardless of its budget.

Another fun way to look at the .85 value is that you’re actually losing 15 cents on every dollar you spend on the project. Yikes! That means for every dollar you spend for labor, you actually only get 85 cents worth. Not a good deal for the project manager. As stated earlier, the closer to 1 the number is, the better the project is performing.

Finding the Schedule Performance Index

The schedule performance index (SPI) measures the project schedule’s overall health. The formula, as Figure 7-10 demonstrates, is earned value divided by planned value. In other words, you’re trying to determine how closely your project work is being completed in relation to the project schedule you created. Let’s try this formula.

Your project with the $500,000 budget is 40 percent complete, for an earned value of $200,000, but you’re supposed to be 45 percent complete by today. That’s a planned value of $225,000. The SPI for this project at this time is determined by dividing the earned value of $200,000 by the planned value of $225,000, for an SPI of .88. This tells me that this project is 88 percent on schedule, or, if you’re a pessimist, the project is 12 percent off track.

Predicting the Project’s Future

Notice in the preceding paragraph I said, “at this time.” That’s because the project will, hopefully, continue to make progress, and the planned value and earned value numbers will change. Naturally, as the project moves toward completion, the earned value amounts will increase, and so will the planned value numbers. Typically, these indexes, both schedule and costs, are measured at milestones, and they allow the project management team to do some prognosticating as to where the project will likely end up by its completion. That’s right—we can do some forecasting.

EXAM TIP The forecasting formulas are swift and easy to calculate, but they’re not really all that accurate. After all, you never really know how much a project will cost until you’ve completed all of the project work.

EXAM TIP The forecasting formulas are swift and easy to calculate, but they’re not really all that accurate. After all, you never really know how much a project will cost until you’ve completed all of the project work.

Finding the Estimate to Complete

So your project is in a pickle, and management wants to know how much more this project is going to cost. They’re after the estimate to complete (ETC) equation. There are three flavors of this formula, based on conditions within your project.

ETC Based on a New Estimate Sometimes you just have to accept the fact that all of the estimates up to this point are flawed, and you need a new estimate. Imagine a project where the project manager and the project team estimate that the work will cost $150,000 in labor, but once they get into the project, they realize it’ll actually cost $275,000 in labor because the work is much harder than they anticipated. That’s a reason for the ETC on a new estimate.

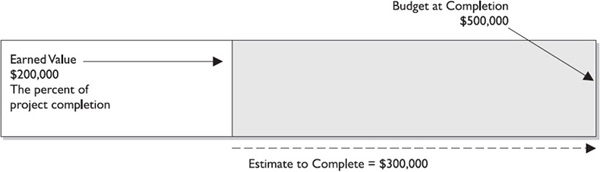

ETC Based on Atypical Variances This formula, shown in Figure 7-11, is used when the project has experienced some wacky fluctuation in costs, and the project manager doesn’t believe the anomalies will continue within the project. For example, the cost of wood was estimated at $18 per sheet. Due to a hurricane in another part of the country, however, the cost of wood has changed to $25 per sheet. This fluctuation in the cost of materials has changed, but the project manager doesn’t believe the cost change will affect the cost to deliver the other work packages in the WBS. Here’s the formula for atypical variances: ETC = BAC – EV.

Let’s say that this project has a BAC of $500,000 and is 40 percent complete. The earned value is $200,000, so our ETC formula would be ETC = $500,000 – $200,000, for an ETC of $300,000. Obviously, this formula is shallow and won’t be the best forecasting formula for every scenario. If the cost of the materials has changed drastically, a whole new estimate would be more appropriate.

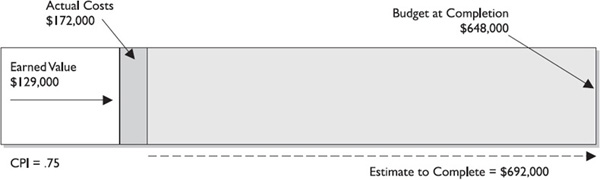

ETC Based on Typical Variances Sometimes in a project, a variance appears and the project management team realizes that this is going to continue through the rest of the project. Figure 7-12 demonstrates the formula: ETC = (BAC – EV)/CPI. For example, consider a project to install 10,000 light fixtures throughout a university campus. You and the project team have estimated it’ll take 12,000 hours of labor to install all of the lights, and your cost estimate is $54 per hour, which equates to $648,000 to complete all of the installations.

As the project team begins work on the install, however, the time to install the light fixtures actually takes slightly longer than anticipated for each fixture. You realize that your duration estimate is flawed and the project team will likely take 16,000 hours of labor to install all of the lights.

The ETC in this formula requires that the project manager know the earned value and the cost performance index. Let’s say that this project is 20 percent complete, so the EV is roughly $129,000. As the work is taking longer to complete, the actual cost to reach the 20 percent mark turns out to be $172,000. The CPI is found by dividing the earned value, $129,000, by the actual costs of $172,000. The CPI for this project is .75.

Now let’s try the ETC formula: (BAC – EV)/CPI, or ($648,000 – $129,000)/.75, which equates to $692,000. That’s $692,000 more that this project will need in its budget to complete the remainder of the project work. Yikes!

Finding the Estimate at Completion

One of the most fundamental forecasting formulas is the estimate at completion (EAC). This formula accounts for all those pennies you’re losing on every dollar if your CPI is less than one. It’s an opportunity for the project manager to say, “Hey! Based on our current project’s health, this is where we’re likely to end up at the end of the project. I’d better work on my resume.” Let’s take a look at these formulas.

EAC Using a New Estimate Just as with the estimate to complete formulas, sometimes it’s best just to create a whole new estimate. This approach with the EAC is pretty straightforward—it’s the actual costs plus the estimate to complete. Let’s say your project has a budget of $500,000, and you’ve already spent $187,000 of it. For whatever reason, you’ve determined that your estimate is no longer valid, and your ETC for the remainder of the project is actually going to be $420,000—that’s how much you’re going to need to finish the project work. The EAC, in this instance, is the actual costs of $187,000 plus your ETC of $420,000, or $607,000.

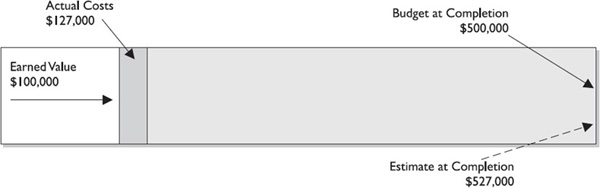

EAC with Atypical Variances Sometimes anomalies within a project can skew the project estimate at completion. The formula for this scenario, as Figure 7-13 demonstrates, is the actual costs plus the budget at completion minus the earned value. Let’s try it. Your project has a BAC of $500,000, and the earned value is $100,000. However, you’ve spent $127,000 in actual costs. The EAC would be $127,000 + $500,000 – $100,000, or $527,000. That’s your new estimate at completion for this project.

EAC Using the CPI If a project has a CPI of .97, you could say the project is losing three pennies on every dollar. Those three pennies are going to add up over time. This approach is most often used when the project manager realizes that the cost variances are likely going to continue through the remainder of the project. This formula, as Figure 7-14 demonstrates, is EAC = AC + ((BAC – EV)/CPI). Don’t you just love nested formulas? Let’s try this one out.

Your project has a BAC of $500,000, and your earned value is $150,000. Your actual costs for this project are $162,000. Your CPI is calculated as .93. The EAC would be $162,000 + (($500,000 – $150,000)/.93), or $538,344. Wasn’t that fun?

EXAM TIP There won’t be as many questions on these EVM formulas as you might hope, but knowing these formulas can help you nail down the few questions you’ll likely have.

EXAM TIP There won’t be as many questions on these EVM formulas as you might hope, but knowing these formulas can help you nail down the few questions you’ll likely have.

Calculating the To-Complete Performance Index

Imagine a formula that would tell you if the project can meet the budget at completion based on current conditions. Or imagine a formula that can predict if the project can even achieve your new estimate at completion. Forget your imagination and just use the To-Complete Performance Index (TCPI). This formula can forecast the likelihood of a project to achieve its goals based on what’s happening in the project right now. There are two different flavors for the TCPI, depending on what you want to accomplish:

• If you want to see if your project can meet the budget at completion, you’ll use this formula: TCPI = (BAC – EV)/(BAC – AC).

• If you want to see if your project can meet the newly created estimate at completion, you’ll use this version of the formula: TCPI = (BAC – EV)/(EAC – AC).

Anything greater than 1 in either formula means that you’ll have to be more efficient than you planned in order to achieve the BAC or the EAC, depending on which formula you’ve used. Basically, the greater the number is than 1, the less likely it is that you’ll be able to meet your BAC or the EAC, depending on which formula you’ve used. The lower the number is than 1, the more likely you are to reach your BAC or EAC (again, depending on which formula you’ve used).

Finding Big Variances

Two variances relate to the entire project, and they’re both easy to learn. The first variance you don’t really know until the project is 100 percent complete. This is the project variance, and it’s simply BAC – AC. If your project had a budget of $500,000 and you spent $734,000 to get it all done, then the project variance is $500,000 – $734,000, which equates, of course, to –$234,000.

The second variance is part of our forecasting model, and it predicts the likely project variance. It’s called the variance at completion (VAC), and the formula is VAC = BAC – EAC. Let’s say your project has a BAC of $500,000 and your EAC is predicted to be $538,344. The VAC is $500,000 – $538,344, for a predicted variance of –$38,344. Of course, this formula assumes that the rest of the project will run smoothly. In reality, where you and I hang out, the project VAC could swing in either direction based on the project’s overall performance.

The Five EVM Formula Rules

For EVM formulas, the following five rules should be remembered:

1. Always start with EV.

2. Variance means subtraction.

4. Less than 1 is bad in an index, and greater than 1 is good. Except for TCPI, which is the reverse.

5. Negative is bad in a variance.

The formulas for earned value analysis can be completed manually or through project management software. For the exam, you’ll want to memorize these formulas. Table 7-1 shows a summary of all the formulas, as well as a sample, albeit goofy, mnemonic device.

DIGITAL CONTENT These aren’t much fun to memorize, I know, but you should. While you won’t have an overwhelming number of EVM questions on your exam, these are free points if you know the formulas and can do the math. I have a present for you—it’s an Excel spreadsheet called “EV Worksheet.” It shows all of these formulas in action. I recommend you make up some numbers to test your ability to complete these formulas and then plug in your values to Excel to confirm your math. Enjoy!

DIGITAL CONTENT These aren’t much fun to memorize, I know, but you should. While you won’t have an overwhelming number of EVM questions on your exam, these are free points if you know the formulas and can do the math. I have a present for you—it’s an Excel spreadsheet called “EV Worksheet.” It shows all of these formulas in action. I recommend you make up some numbers to test your ability to complete these formulas and then plug in your values to Excel to confirm your math. Enjoy!

Chapter Summary

Projects require resources and time, both of which cost money. Projects are estimated, or predicted, according to how much the project work will likely cost to complete. There are multiple flavors and approaches to project estimating. Project managers can use analogous estimating, parametric estimating, or, the most reliable, bottom-up estimating. Whatever estimating approach the project manager elects to use, the basis of the estimate should be documented in case the estimate should ever be called into question.

When a project manager creates the project estimate, he should also factor in a contingency reserve for project risks and cost overruns. Based on the enterprise environmental factors of an organization, and often the project priority, the process to create and receive the contingency reserve may fluctuate. The contingency reserve is not an allowance to be spent at the project manager’s discretion but more of a safety net should the project go awry. Variances covered by the contingency reserve can’t be swept under the rug, but must be accounted for and hopefully learned from.

Cost budgeting is the aggregation of the costs to create the work packages in the WBS. Sometimes, cost budgeting refers to the cost aggregation as the “roll-up” of the costs associated with each work package. Cost budgeting effectively applies the cost estimates over time. Most project managers don’t receive the entire project funding in one swoop, but rather in step functions over the life of the project.

Once the project moves from planning into execution, it also moves into monitoring and control. The project manager and the project team work together to control the project costs and monitor the performance of the project work. The most accessible method to monitor the project cost is through earned value management. Earned value management demonstrates the performance of the project and allows the project manager to forecast where the project is likely to end up financially.

Key Terms

Actual cost (AC) The actual amount of monies the project has spent to date.

Analogous estimating An approach that relies on historical information to predict the cost of the current project. It is also known as top-down estimating and is the least reliable of all the cost-estimating approaches.

Bottom-up estimating An estimating approach that starts from zero, accounts for each component of the WBS, and arrives at a sum for the project. It is completed with the project team and can be one of the most time-consuming and most reliable methods to predict project costs.

Budget estimate This estimate is also somewhat broad and is used early in the planning processes and also in top-down estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –10 percent to +25 percent.

Commercial database A cost-estimating approach that uses a database, typically software-driven, to create the cost estimate for a project.

Contingency reserve A contingency allowance to account for overruns in costs. Contingency allowances are used at the project manager’s discretion and with management’s approval to counteract cost overruns for scheduled activities and risk events.

Cost aggregation Costs are parallel to each WBS work package. The costs of each work package are aggregated to their corresponding control accounts. Each control account then is aggregated to the sum of the project costs.

Cost baseline A time-lapse exposure of when the project monies are to be spent in relation to cumulative values of the work completed in the project.

Cost budgeting The cost aggregation achieved by assigning specific dollar amounts for each of the scheduled activities or, more likely, for each of the work packages in the WBS. Cost budgeting applies the cost estimates over time.

Cost change control system A system that examines any changes associated with scope changes, the cost of materials, and the cost of any other resources, and the associated impact on the overall project cost.

Cost management plan The cost management plan dictates how cost variances will be managed.

Cost of poor quality The monies spent to recover from not adhering to the expected level of quality. Examples may include rework, defect repair, loss of life or limb because safety precautions were not taken, loss of sales, and loss of customers. This is also known as the cost of nonconformance to quality.

Cost of quality The monies spent to attain the expected level of quality within a project. Examples include training, testing, and safety precautions.

Cost performance index (CPI) Measures the project based on its financial performance. The formula is CPI = EV/AC.

Cost variance (CV) The difference of the earned value amount and the cumulative actual costs of the project. The formula is CV = EV – AC.

Definitive estimate This estimate type is one of the most accurate. It’s used late in the planning processes and is associated with bottom-up estimating. You need the WBS in order to create the definitive estimate. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –5 percent to +10 percent.

Direct costs Costs are attributed directly to the project work and cannot be shared among projects (for example, airfare, hotels, long-distance phone charges, and so on).

Earned value (EV) Earned value is the physical work completed to date and the authorized budget for that work. It is the percentage of the BAC that represents the actual work completed in the project.

Estimate at completion (EAC) These forecasting formulas predict the likely completed costs of the project based on current scenarios within the project.

Estimate to complete (ETC) An earned value management formula that predicts how much funding the project will require to be completed. Three variations of this formula are based on conditions the project may be experiencing.

Fixed costs Costs that remain constant throughout the life of the project (the cost of a piece of rented equipment for the project, the cost of a consultant brought on to the project, and so on).

Funding limit reconciliation An organization’s approach to managing cash flow against the project deliverables based on a schedule, milestone accomplishment, or data constraints.

Indirect costs Costs that are representative of more than one project (for example, utilities for the performing organization, access to a training room, project management software license, and so on).

Known unknown An event that will likely happen within the project, but when it will happen and to what degree is unknown. These events, such as delays, are usually risk-related.

Learning curve An approach that assumes the cost per unit decreases the more units workers complete, because workers learn as they complete the required work.

Oligopoly A market condition where the market is so tight that the actions of one vendor affect the actions of all the others.

Opportunity cost The total cost of the opportunity that is refused to realize an opposing opportunity.

Parametric estimating An approach using a parametric model to extrapolate what costs will be needed for a project (for example, cost per hour and cost per unit). It can include variables and points based on conditions.

Planned value (PV) Planned value is the work scheduled and the budget authorized to accomplish that work. It is the percentage of the BAC that reflects where the project should be at this point in time.

Project variance The final variance, which is discovered only at the project’s completion. The formula is VAR = BAC – AC.

Regression analysis This is a statistical approach to predicting what future values may be, based on historical values. Regression analysis creates quantitative predictions based on variables within one value to predict variables in another. This form of estimating relies solely on pure statistical math to reveal relationships between variables and to predict future values.

Reserve analysis Cost reserves are for unknown unknowns within a project. The management reserve is not part of the project cost baseline, but is included as part of the project budget.

Rough order of magnitude This rough estimate is used during the initiating processes and in top-down estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –25 percent to +75 percent.

Schedule performance index (SPI) Measures the project based on its schedule performance. The formula is SPI = EV/PV.

Schedule variance (SV) The difference between the earned value and the planned value. The formulas is SV = EV – PV.

Single source Many vendors can provide what your project needs to purchase, but you prefer to work with a specific vendor.

Sole source Only one vendor can provide what your project needs to purchase. Examples include a specific consultant, specialized service, or unique type of material.

Sunk costs Monies that have already been invested in a project.