5

Surpass Your Limits

PERSONAL ABILITY

It’s a funny thing, the more I practice the luckier I get.

—Arnold Palmer

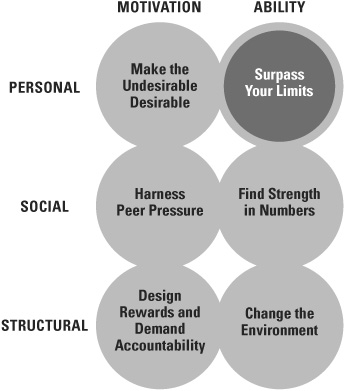

In Chapter 4 we examined ways to tap into personal passions as a way of influencing vital behaviors. To that we add that we can limit our success when we assume that any influence failure is exclusively a motivation problem. We commit what psychologist Lee Ross calls the fundamental attribution error.” We assume that when people don’t change, it’s simply because they don’t want to change. In making this simplistic assumption, we lose an enormous lever for change.

Even when we do realize that people may lack the ability required to enact a vital behavior, we often underestimate the need to learn and actually practice that behavior. Corporate leaders make this mistake when they send employees to an intensive day of leadership training that consists of flipping through a binder or listening to engaging stories—but not actually trying any of the skills being taught. Participants mistakenly assume that knowing the leadership content and doing it are one and the same. Of course, they aren’t the same at all, so participants usually return to the office and apply only a fraction of what they studied.

When leaders and training designers combine too much motivation with too few opportunities to improve ability, they don’t produce change; they create resentment and depression. Influence masters take the opposite tack. They overinvest in strategies that help increase ability. They avoid trying to solve ability problems with stronger motivational techniques.

To see how easy it is to confuse motivation and ability problems, let’s return to Henry—our friend who is trying to lose weight.

THERE’S HOPE FOR EVERYONE

One of Henry’s vital behaviors—snacking on mini carrots rather than chocolate—is at risk. At this very moment, Henry is pulling the foil back on a partially eaten, two-pound chocolate bar. In Henry’s defense, he didn’t buy it. A colleague who knew of his deep affection for chocolate gave it to him. The tempting bar sat on his desk for over a week.

Moments ago Henry decided to heft the plank-sized confection merely to see what two pounds felt like. When he did, he noticed that the adhesive holding the wrapper around the inner foil lining had failed. It appeared as if it was about to fall away, seductively revealing the beautiful red, shiny foil beneath it—the last defense before the chocolate itself.

Henry tugged at the wrapper playfully, and with almost no effort it came free. The next few seconds were almost a blur. Without thinking, Henry’s hands peeled back the top flap of the foil and exposed the rich chocolate. In a rush, chocolate-filled childhood memories poured through his head as his fingers pried loose a single dark brown section—a modest, harmlessly small packet of pleasure. He brought the treat to his lips—and then it was over. The chocolate began its inexorable transformation from cocoa, fat, and sugar to cellulite.

Here’s the problem. At the moment when Henry should be enjoying one of his secret pleasures, he’s depressed. As he now gobbles down the chocolate, with each bite he’s convinced that he strayed from his diet because he lacks the proper strength of character. It’s clear that he doesn’t have moxie or willpower. In short, he’s a weak person. Up until this sad indulgence, he had valiantly cut back on calories while sincerely promising himself to start an exercise regime. This new, iron-willed Henry ruled for eight full days. And then the mere touch of the red foil lining brought him to ruin.

Henry wonders if he can overcome the genetic hand that he’s been dealt. He has neither self-discipline to diet nor the athletic prowess to exercise effectively. Surely he’s doomed to a life of huffing and puffing. But then again, unbeknownst to Henry, a long line of research suggests that maybe he isn’t doomed at all. There’s a good chance that he can actually learn what it takes to withstand the temptations of chocolate as well as how to improve his ability to exercise properly.

In fact, many of the stories Henry has been carrying in his head since he was a young man may be equally wrong. When his mother once told him that he wasn’t exactly a gifted speaker and later when his father suggested that leadership “wasn’t his thing,” Henry believed that he hadn’t been born with “the right stuff.” He wasn’t born to be an elite athlete; that’s for certain. Later he learned that music wasn’t his thing, and his interpersonal skills weren’t all that strong. Later still he discovered that spending in excess, getting hooked on video games, and gorging on Swiss chocolate were his thing. But none of this is going to change because Henry, like all humans, can’t fight genetics.

Fortunately, Henry is dead wrong. Henry is trapped in what Carol Dweck, a researcher at Stanford, calls a “fixed mindset.” If he believes he can’t improve, then he won’t even try, and he’ll create a self-fulfilling prophecy. But Henry is in luck. Genes don’t play the fatalistic role scholars once assumed they played in determining physical prowess, mental agility, and yes, even self-discipline. Characteristics that had long been described by scholars and philosophers alike as genetic gifts or lifelong personality traits appear to be learned, much the same way one learns to walk, talk, or whistle. That means that Henry doesn’t need to accept his current status. He can adopt what Dweck refers to as a “growth mindset.” Henry simply needs to learn how to develop a set of high-level learning skills and techniques that influence masters use all the time. He needs to learn how to learn. Henry, like most of us, was actually born with the right stuff; he just hasn’t figured out how to get it to work for him yet.

To illustrate, let’s consider the lengthy hunt researchers conducted in a quest to find the all-important trait of self-discipline. Here was a personality trait worth studying. If the ability to withstand the alluring smell of chocolate or the siren call of buying shiny new products before you have the cash to pay for them—the ability to delay gratification—isn’t a reflection of one’s underlying character, then what is?

Professor Walter Mischel of Stanford University, curious about people’s inability to withstand temptations, set out to explore this issue. Did certain humans have the right stuff while others didn’t? And if so, did the right stuff affect lifelong performance? What Mischel eventually came to understand altered the psychological landscape forever.

MUCH OF WILL IS SKILL

When “Timmy,” age four, sat down at the gray metal table in an experimental room in the basement of Stanford’s psychology department, the child saw something that caught his interest. On the table was a marshmallow—the kind Timmy’s mom put into his cup of hot chocolate. Timmy really wanted to eat the marshmallow.

The kindly man who brought Timmy into the room told him that he had two options. The man was going to step out for a moment. If Timmy wanted to eat the marshmallow, he could eat away. But if Timmy chose to wait a few minutes until the man returned, then Timmy could eat two marshmallows.

Then the man exited. Timmy stared at the tempting sugar treat, squirmed in his chair, kicked his feet, and in general tried to exercise self-control. If he could wait, he’d get two marshmallows! But the temptation proved too strong for little Timmy, so he finally reached across the table, grabbed the marshmallow, looked around nervously, and then shoved the spongy treat in his mouth. Apparently Timmy and Henry are kindred spirits.

Actually, Timmy was one of dozens of subjects Dr. Mischel and his colleagues studied for more than four decades. Mischel was interested in learning what percentage of his young subjects could delay gratification and what impact, if any, this character trait would have on their adult lives. Mischel’s hypothesis was that children who were able to demonstrate self-control at a young age would enjoy greater success later in life because of that trait.

In this and many similar studies, Mischel followed the children into adulthood. He discovered that the ability to delay gratification had a more profound effect than many had originally predicted. Notwithstanding the fact that the researchers had watched the kids for only a few minutes, what they learned from the experiment was enormously telling. Children who had been able to wait for that second marshmallow matured into adults who were seen as more socially competent, self-assertive, dependable, and capable of dealing with frustrations; and they scored an average of 210 points higher on their SATs than people who gulped down the one marshmallow. The predictive power was truly remarkable.

Companion studies conducted over the next decade with people of varying ages (including adults) confirmed that individuals who exercise self-control achieve better outcomes than people who don’t. For example, if high schoolers are good at self-control, they experience fewer eating and drinking problems. University students with more self-control earn better grades, and married and working people have more fulfilling relationships and better careers. And as you might suspect, people who demonstrate low levels of self-control show higher levels of aggression, delinquency, health problems, and so forth.

Apparently, Mischel had stumbled onto the mother lode of personality traits. Kids who had been blessed with the innate capacity to withstand short-term temptations fared better throughout their entire lives. The fact that a four-year-old’s onetime response to a sugary confection predicts lifelong results is at once exciting and depressing—depending on whether you are a “grabber” or a “delayer.” You’re either well fitted to take on the temptations of the world or doomed to a lifelong fate of enjoy now, pay later—as might well be the lot of our friend Henry.

But is this what’s really going on in these studies? Are some people wired to succeed and others to fail?

One thing was clear from these studies: The ability to delay gratification did predict a large number of long-term results. That part of the marshmallow research nobody was arguing about. However, for years scientists continued to debate the cause of this strong effect. Did self-control stem from an intractable personality characteristic or something more malleable and thus learnable?

In 1965, Dr. Mischel collaborated on a study with Albert Bandura who openly challenged the assumption that will was a fixed trait. Always a student of human learning, Bandura worked with Mischel to design an experiment to test the stability of subjects who had delayed gratification. In an experiment similar to the marshmallow studies, the two scholars observed fourth- and fifth-graders in similar circumstances. They placed children who had not demonstrated that they could delay gratification into contact with adult role models who knew how to delay. The greedy kids observed adults who put their heads down for a nap or who got up from the chair and engaged in some distracting activity. The original “grabbers” saw techniques for delaying gratification. And to everyone’s delight, they followed suit.

After a single exposure to an adult model, children who previously hadn’t delayed suddenly became stars at delaying. Even more interesting, in follow-up studies conducted months later, the children who had learned to delay retained much of what they’d learned during the brief modeling session. So what about those hardwired genetic characteristics or traits that had predicted so much?

The answer to this important question is good news to all of us and most certainly offers hope to Henry. When Mischel took a closer look at individuals who routinely held out for the greater reward, he concluded that delayers are simply more skilled at avoiding short-term temptations. They didn’t merely avoid the temptation; they employed specific, learnable techniques that kept their attention off what would be merely short-term gratification and on their long-term goal of earning that second marshmallow.

So maybe Henry can learn how to delay gratification—if he learns tactics that will help him do so. But will that be enough to transform him into the physically fit person he’d like to become? After all, he’s not good at jogging or weight lifting either. In fact, he’s horrible at all things athletic. Surely factors as hardwired as body type, lung capacity, and musculature are predictors of good athletic performance. Henry has no hope of ever becoming one of those chiseled hunks you see hanging out at health clubs. Or does he?

MUCH OF PROWESS IS PRACTICE

Psychologist Anders Ericsson offers an interesting interpretation of how those at the top of their game get there. He doesn’t believe for a second that elite-level performance stems from zodiacal forces or, for that matter, from enhanced mental or physical properties. After devoting his academic life to learning why some individuals are better at certain tasks than others, Ericsson has been able to systematically demonstrate that people who climb to the top of just about any field eclipse their peers through something as basic as deliberate practice.

We’ve all heard the old saw that practice doesn’t make perfect, perfect practice makes perfect. Ericsson has spent his life proving this to be true. While most people believe that they are born with inherent limits to their athletic ability, Ericsson argues that there is little evidence that people who achieve exceptional performance ever get there through any means other than carefully guided practice—perfect practice. His research demonstrates that prowess, excellence, elite status—call it what you like—is not a matter of genetic gifts; it’s a matter of knowing how to enhance your skills through deliberate practice.

For instance, Ericsson describes how dedicated figure skaters practice differently on the ice: Olympic hopefuls work on skills they have yet to master. Club skaters, in contrast, work on skills they’ve already mastered. Amateurs tend to spend half of their time at the rink chatting with friends and not practicing at all. Put simply, skaters who spend the same number of hours on the ice achieve very different results because they practice in very different ways. In Ericsson’s research, this finding has held true for every skill imaginable, including memorizing complex lists, playing chess, excelling at the violin, and conquering every extant sporting skill. It also applies to more complex interactions such as giving speeches, getting along with others, and holding emotional, sensitive, or high-stakes conversations.

Before we move on, let’s take care to avoid a very large and dangerous trap. The fact that improvements in performance come through deliberate practice makes all the sense in the world when it comes to activities such as figure skating, playing chess, and mastering the violin. However, few people, if any, would think of practicing with a coach to learn how to get along with coworkers, motivate team members to improve their quality measures, emotionally connect with a troubled teen, or talk to a physician about a medical error. Most of us don’t even think that soft and gushy interpersonal skills are something you need to study at all, let alone something you’d study and practice with a coach.

But that’s precisely what should be going on. Consider a common problem at hospitals. A surgeon has just committed a medical error. While performing a mastectomy, she’s accidentally ripped a tiny muscle guarding the patient’s chest cavity. The anesthesiologist sees a gauge jump, so it appears as if one lung is no longer taking in air. Two of the nurses assisting the operation see similar signs of distress. If the medical team doesn’t start corrective action soon, the patient could die. But before this happens, either the surgeon needs to take responsibility or one of the other professionals needs to raise an alarm.

Let’s focus on staff members who are assisting and predict what they might do. Most would certainly hesitate for a few seconds before suggesting that the surgeon has just made a mistake. They’ll hesitate because if they don’t handle the situation well, they’ll come off as flippant or even insubordinate. There are legal issues at play, and that only makes the discussion that much more delicate. Worse still, they’ve seen colleagues who’ve expressed a concern, turned out to be wrong, and then received a tongue-lashing. Better to let someone else take the risk. Precious seconds continue to pass.

This and tens of thousands of similar medical errors continue to happen because individuals who may have practiced drawing blood or moving a patient or reading a gauge dozens of times haven’t studied and practiced how to confront a colleague—or even more frightening—a physician. They aren’t exactly sure what to say and how to say it. They certainly lack the confidence that comes from having practiced.

Of course, health care isn’t the only field in which a lack of interpersonal know-how has caused serious problems. Every time a boss expresses a half-baked, even dangerous, idea and subordinates bite their tongues for fear of being chastised, good ideas remain a secret and teams make bad decisions. Speaking up to an authority figure requires skill, and skill requires practice. The same is true for confronting a mentally abusive spouse or dealing with a bully at school or—here’s a hot one—just saying no to drugs. Try that without getting ridiculed or beat up. Interpersonal interactions can be extraordinarily complicated, and most will improve only after individuals receive instruction that includes deliberate practice.

Consider the problem Dr. Wiwat Rojanapithayakorn faced when attempting to encourage young, poor, shy, female sex workers to deny services to older, richer male customers if the customers refused to use a condom. At first the young girls mumbled their disapproval, only to be intimidated by their vocal clients. Not knowing what to say or how to say it, they’d quickly give in and put themselves and thousands of others at risk.

Eventually Wiwat asked more seasoned sex workers to train young girls on how to defend their health. They shared actual scripts that helped them avoid offending the customer while at the same time holding a firm line. Equally important, the young women actually practiced the conversation until they had gained confidence in what they were going to say and how they would say it. They continued to practice and receive feedback until they had mastered their scripts well enough to actually use them at work. In this particular case, providing detailed coaching and feedback helped compliance with the strict condom code rise from 14 percent to 90 percent in just a few years—saving millions of lives.

Many of the profound and persistent problems we face stem more from a lack of skill (which in turn stems from a lack of deliberate practice) than from a genetic curse, a lack of courage, or a character flaw. Self-discipline, long viewed as a character trait, and elite performance, similarly linked to genetic gifts, stem from the ability to engage in guided practice of clearly defined skills. Learn how to practice the right actions, and you can master everything from withstanding the temptations of chocolate to holding an awkward discussion with your boss.

PERFECT COMPLEX SKILLS

Let’s return to a point we made earlier. Not all practice is good practice. That’s why many of the tasks we perform at work and at home suffer from “arrested development.” With simple tasks such as typing, driving, golf, and tennis, we reach our highest level of proficiency after about 50 hours of practice; then our performance skills become automated. We’re able to execute them smoothly and with minimal effort, but further development stops. We assume we’ve reached our highest performance level and don’t think to learn new and better methods.

With some tasks, we stop short of our highest level of proficiency on purpose. The calculus we perform in our heads suggests that the added effort it’ll take to find and learn something new will probably yield a diminishing marginal return, so we stop learning. For instance, we learn how to make use of a word processor or Web server by mastering the most common moves, but we never learn many of the additional features that would dramatically improve our ability.

This same pattern of arresting our development applied over an entire career yields fairly unsatisfactory results. For example, most professionals progress until they reach an “acceptable” level, and then they plateau. Software engineers, for instance, usually reach their peak somewhere around five years after entering the workforce. Beyond this level of mediocrity, further improvements are not correlated to years of work in the field.

So what does create improvement? According to Dr. Anders Ericsson, improvement is related not just to practice, but to a particular kind of practice—something Ericsson calls deliberate practice. Ericsson has found that no matter the field of expertise, when it comes to elite status, there is no correlation whatsoever between time in the profession and performance levels.

The implications are stunning. A 20-year-veteran brain surgeon is not likely to be any more skilled than a 5-year rookie by virtue of time on the job. Any difference between the two would have nothing to do with experience and everything to do with deliberate practice. Time is required (most elite performers in fields such as music composition, dance, science, fiction writing, chess, and basketball have put in 10 or more years), but it is not the critical variable for mastery. The critical factor is using time wisely. It’s the skill of practice that makes perfect.

Most of us already have all the evidence we need to confirm that deliberate practice can have an enormous effect on performance levels. Just look at what’s happened to our capacity to teach everything from mathematics to high jumping. Roger Bacon once said that it would take a person 30 to 40 years to master calculus—the same calculus that is taught in most high schools today. Today’s musicians routinely match and even surpass the technical virtuosity of legendary musicians of the past. And when it comes to sports, the records just keep falling. For example, when Johnny Weissmuller of Tarzan fame won his five Olympic gold medals in swimming in 1924, nobody expected that years later high school kids would post better times.

What, then, is deliberate practice? And how can we apply the techniques to our vital behaviors and thus strengthen our influence strategy?

Demand Full Attention for Brief Intervals

Deliberate practice requires complete attention. Deliberate practice doesn’t allow for daydreaming, functioning on autopilot, or only partially putting one’s mind into the routine. It requires steely-eyed concentration as students watch exactly what they’re doing, what is working, what isn’t, and why.

This ability to concentrate is often viewed by students as their most difficult challenge, enough so that elite musicians and athletes argue that maintaining their concentration is usually the limiting factor to deliberate practice. Most can maintain a heightened level of concentration for only an hour straight, usually during the morning when their minds are fresh. Across a wide range of disciplines, the total daily practice time of elite performers rarely exceeds five hours a day, and this only if students take naps and sleep longer than normal.

Provide Immediate Feedback Against a Clear Standard

The number of hours one spends practicing a skill is far less important than receiving clear and frequent feedback against a known standard. For example, serious chess players spend about four hours a day comparing their play to the published play of the world’s best players. They make their best move, and then compare it to the move the expert made. When their move is different from the master’s, they pause to determine what the expert saw and they missed. As a result of comparing themselves to the best, students improve their skills much faster than they would otherwise. This immediate feedback, coupled with complete concentration, accelerates learning. Players know quickly when they are off course, and they learn from their own poor moves.

As you might imagine, sports stars require rapid feedback to improve performance as well. They tend to focus on small but vital aspects of their play and scrupulously compare one round to the next. Swimming gold medalist Natalie Coughlin completes each leg of her races with fewer strokes than her opponents, giving her a tremendous advantage in stamina. Her practice is focused on the minute details of each stroke. She explains: “You’re constantly manipulating the water. The slightest change in pitch in your hand makes the biggest difference.” At the conclusion of each lap, Natalie is acutely aware of the number of strokes she took to complete it, and she adjusts her hand position for the next lap. This kind of focused, deliberate practice enhances performance more rapidly than does merely swimming laps.

This concept of rapid feedback stands traditional teaching methods on their heads. Many teachers believe that tests are painful experiences that should be given as infrequently as possible so as not to discourage students. Research reveals that the opposite is true. Ethna Reid taught us that one of the vital behaviors for effective teachers is extremely short intervals between teaching and testing. When testing comes frequently, it becomes familiar. It’s no longer a dreaded, major event. It provides the chance for people to see how well they’re doing against the standard.

Think about how deliberate practice with clear feedback compares with the way we currently train our leaders. Rarely do business school and management faculties think of leadership as a performance art. Faculty members typically teach leaders how to think, not how to act. So when would-be executives take MBA courses or graduate executives attend leadership training, they’re routinely asked to read cases, apply algorithms, and the like, but there’s a good chance that they’ll never be asked to practice anything.

Granted, business schools typically offer a course in giving presentations and speeches where the performance components that students are asked to practice are so obvious. But this is not the case with other important leadership skills, such as addressing controversial topics, confronting bad behavior, building coalitions, running a meeting, disagreeing with authority figures, or influencing behavior change—all of which call for specific behaviors, and all of which can and must be learned through deliberate practice.

Break Mastery into Mini Goals

Let’s add another dimension to deliberate practice. We start with a test. How would you motivate patients to take pills that one day might prevent them from experiencing a stroke? If they’ve already had one stroke, you’d think it would be easy to get them to take the lifesaving pills. But let’s add a confounding factor. The pills often cause leg cramps, painful rashes, loss of energy, constipation, headaches, and sexual dysfunction. So patients take a pill, and they will most assuredly suffer short-term results, but maybe they won’t have a stroke sometime way out in the future. This is going to be a hard sell. In fact, for years many stroke patients didn’t take their pills because they didn’t like the odds.

This all changed when researchers stopped focusing on long-term goals (avoiding another stroke) and created a regimen that helped patients set mini goals and then provided rapid feedback against them. Researchers gave patients packets of pills, a blood pressure monitor, and a log book. Every day they took the pills, monitored their blood pressure, and recorded changes in the log book along with other achievements. The change was dramatic and immediate. By setting small goals (daily monitoring and recording) and meeting them, patients now focused on something they could see and control. This enhanced their sense of efficacy, clarified the effect of the medicine, and motivated compliance. Now these patients take their pills.

Influence masters have long known the importance of setting clear and achievable goals. First, they understand the importance of setting specific goals. People say that they understand this concept, but few actually put the concept into practice. For example, average volleyball players set goals to improve their “concentration” (exactly what is that?), whereas top performers decide they need to practice tossing the ball correctly—and they understand each of the elements in the toss.

As part of this focus on specific levels of achievement, top performers set their goals to improve behaviors or processes rather than outcomes. For instance, top volleyball performers set process goals aimed at the set, the dig, the block, and so on. Mediocre performers set outcome goals such as winning so many points or garnering applause. In basketball, players who routinely hit 70 percent or more of their free throws tend to practice differently from those who hit 55 percent or less. How? Better shooters set technique-oriented goals such as, “Keep the elbow in,” or, “Follow through.” Players who shoot 55 percent and under tend to think more about results-oriented goals such as, “This time I’m going to make ten in a row.”

This difference in focus is also borne out when players blow it. Researchers stopped players who missed two free throws in a row and asked them to explain their failure. Master shooters were able to cite the specific technique they got wrong. (“I didn’t keep my elbow in.”) Poorer shooters offered vague explanations such as, “I lost concentration.”

The role of mini goals in maintaining motivation also deserves attention. With certain skills, people are deathly afraid that they won’t succeed. And once they do fail, they fear that bad things will happen to them. As you might imagine, when people predict that their actions will lead to catastrophic results, these failure stories lead to self-defeating behavior. Individuals begin with the hypothesis that they will never succeed and that the failure will be costly, and then they look for every shred of proof that they’re about to fail so they can bail out early before they suffer too much—which they do anyway.

When fear dominates people’s expectations, not only do you have to improve their actual skill, but you have to take special care to ensure that their expectations of success grow right along with their actual ability. But how? As we learned earlier, simply using verbal persuasion isn’t enough to convince them. (“Go ahead, the snake won’t bite!”) For example, in one line of research scholars learned that you can teach dating skills to shy sophomores, but the students need to see proof of constant progress before they’re willing to admit that they’ve learned anything useful or before they put the new skills into practice.

And where do people find this proof of progress? From progress itself. Nothing succeeds like success. As people succeed, they learn through personal experience (the real deal for changing understanding, which can be a powerful tool for changing minds) that they actually can achieve their goals. Unfortunately, skeptical people aren’t likely to attempt behaviors that they perceive to be risky, so they never succeed. Now what’s a person to do?

Dr. Bandura points out that to encourage people to attempt something they fear, you must provide rapid positive feedback that builds self-confidence. You achieve this by providing short-term, specific, easy, and low-stakes goals that specify the exact steps a person should take. Take complex tasks and make them simple; long tasks and make them short; vague tasks and make them specific; and high-stakes tasks and make them risk free.

If you want to see how to put short-term, specific, easy, low-stakes goals into play on a much grander scale, take a look at our friends at Delancey Street. The entering criminals and societal castoffs that Dr. Silbert works with are typically illiterate and completely unskilled. Not only do they not have job expertise or academic talent, but they also lack interpersonal and social survival skills.

So what do you do when you have to teach residents dozens or even hundreds of skills? You eat the elephant one bite at a time. You select one domain, say a vocational skill such as working in a restaurant, then choose a small skill in that area. For example, on the very first night you teach the nervous newcomer how to set a table—maybe just the forks. Then, this novice who is very likely to be suffering from drug withdrawal along with culture shock and other physical and emotional problems practices placing the fork until he or she gets it right. Next comes the knife.

Prepare for Setbacks; Build In Resilience

As important as it is to use baby steps to ensure short-term success during the early phases of learning, if subjects experience only successes early on, then failures can quickly discourage them. A short history of easy successes can create a false expectation that not much effort is required. Then if subjects run into a problem, they become discouraged.

To deal with this problem, people need to learn that effort, persistence, and resiliency are eventually rewarded with success. Consequently, the practice regime should gradually introduce tasks that require increased effort and persistence. As learners overcome more difficult tasks and recover from intermittent defeats, they see that setbacks aren’t permanent roadblocks, but signals that they need to keep learning.

This capacity to tell ourselves the right story about problems and setbacks is particularly important when we’re already betting against ourselves. When faced with a setback, we need to learn to say, “Aha! I just discovered what doesn’t work,” and not, “Oh no! Once again I’m an utter failure.” We need to interpret setbacks as guides, and not as brakes.

Initially, failure signals the need for greater effort or persistence. Sometimes failure signals the need to change strategies or tactics. But failure should rarely signal that we’ll never be able to succeed and drive us to pray for serenity. For instance, you find yourself staring at a half-eaten ice cream cone in your hand. Should you conclude that you’re unable to stick with your eating plan so you might as well give up? Or should you conclude that since it’s hard to resist when you walk past the ice cream parlor on your way home from work, you should change your route? The first conclusion serves as a discouraging brake on performance, whereas the second provides a corrective guide that helps refine your strategy.

BUILD EMOTIONAL SKILLS

Let’s end our exploration into self-mastery where we began. Henry is staring down at his half-opened chocolate bar. His eyes, lips, and taste buds are prodding his brain to satisfy their demands. He wants chocolate. To see if Henry is doomed—or if he can learn a skill to help him delay gratification—let’s turn to research that helps us better understand the original marshmallow study.

Contemporary research reveals that human beings operate in two very different modalities, depending on the circumstances. However, as Mischel and Bandura informed us, these modalities or systems are viewed less as character traits or impulses and more as behaviors that can be regulated through skill. The first of these two operating modalities is referred to by contemporary theorists as our “hot” or “go” system. It helps us survive. We stumble upon something threatening—say a tiger—and as our “go” system takes over, our brain sends blood to our arms and legs, our heart rate and blood pressure increase, and, like it or not, we start producing cholesterol—just in case we face blunt trauma.

More intriguing still, as our “go” system kicks in and blood flows out of the brain and toward our arms and legs, we start relying on a much smaller part of our brain (the amygdala) to take over the job of “thinking.” When the amygdala takes control, we no longer process information in a cool, calm, and collected way. Rather than cogitating, ruminating, and completing other high-level cognitive tasks, the amygdala or “reptilian brain” is made for speed. It’s wired for quick, emotional processing that, when activated, triggers reflexive responses including fight and flight. The amygdala instinctively moves us to action. We see a tiger and bang, we’re off and running. This hot/go system develops very early and is most dominant in the young infant.

The second system, known as the “cool” or “know” system, serves us well during more stable times. It’s emotionally neutral, runs off the frontal lobe, and is designed for higher-level cognitive processing. Consequently, it helps us thrive, rather than survive. It’s the part of the brain we’re using as we’re calmly picking blackberries while chatting with a friend. This system is very ill suited to dealing with the tiger that is just about to appear around the corner. Our “know” system is slow and contemplative and begins to develop at around age four—just about the time children are first able to delay gratification.

As terrific as it is to have two very different operating systems, each perfectly suited to its own unique tasks, when you have two of anything, you always run the risk of employing the wrong one given your circumstances. For instance, a tiger appears, and you remain emotionally neutral, marveling at the cat’s amazing speed, while you carefully contemplate your options. “Let’s see, if I climb that tree, there’s a chance …” Too late—you’re tiger food. Too bad your “know” system had wrestled control away from your “go” system.

To be honest, calling up our “know” system when it’s our “go” system that would serve us better isn’t all that common. It’s the “go” system we call into service every chance we get. After all, it’s better to run at the first sign of danger than remain mired in the “know” too long. Consequently, the “go” system often turns on at the mere hint that you’re about to fall under attack. Heaven forbid you think complexly and clearly in such a case.

For example, an accountant who works with you makes fun of an idea you offer up in a meeting. This ticks you off. How dare this knuckle-dragging bean counter mock your idea! Of course, this isn’t exactly a life-threatening circumstance you face; it’s an accountant, not a tiger. Nevertheless, better safe than sorry. So, like it or not, your “go” system kicks in. In fact, it does so without your even asking for help. As your blood starts rushing to your arms and legs where it can do some good, your brain will just have to run off the amygdala. You’re hot, you’re ready to go, you’re not the least bit contemplative, and you verbally tear into the poor fellow from accounting like an early human on a fallen woolly mammoth. What were you thinking? More to the point, what part of your brain were you thinking with?

This inappropriate emotional reaction is exactly the same thing that happens whenever your appetites or cravings kick in at a moment you would prefer that they remain less active. Your “go” system isn’t designed merely for fight or flight; it’s also designed to take charge whenever a quick, reflexive, survival behavior might suit you. For example, you smell fresh donuts as you walk by the company cafeteria, and an urge from within whispers, “Eat now before it’s too late.”

So there you have it. Sometimes we switch into the wrong version of our two operating systems, and this change causes us huge problems. That’s why in spite of the fact that we’re committed to a vital behavior, we often crumble at stressful moments. If only we could learn how to wrestle control away from the amygdala when it’s kicking in hard at the wrong time. Then perhaps we could be ruled by reason, and not let passion take charge. The good news is that this powerful self-management skill is learnable. And if you want to equip yourself or others to survive the tide of opposing emotions, this skill is pivotal.

KICK-START OUR BRAIN

To learn how to take charge of our “go” system, let’s return to the marshmallow studies. Once Mischel and others had divided their research subjects into “grabbers” and “delayers,” they turned their attention to transforming everyone into a delayer. What would it take to help people survive immediate temptations in order to achieve long-term benefits? More importantly, they wanted to avoid the mistake of relying on verbal persuasion by simply telling people to gut it out, or to “show some self-control!” Instead, they wanted to teach people the skills associated with emotional management. But what were these skills?

Mischel discovered through a series of experiments with varied age groups and rewards that if subjects didn’t trust that the researcher would actually return and give them the longer-term reward, they wouldn’t delay. Why hold out only to be disappointed? Similarly, if subjects believed that they wouldn’t be able to do what it took to withstand the short-term temptation, they also wouldn’t delay. In short, Mischel confirmed what Bandura taught us earlier. People won’t attempt a behavior unless: (1) they think it’s worth it, and (2) they think they can do what’s required. If not, why try?

In his original experiments, Mischel had observed that children who were able to delay gratification were better at distracting themselves from thinking about either the short- or the long-term reward. Delayers managed their emotions by distracting themselves with other activities. They avoided looking at the marshmallows by covering their eyes, turning their chairs away, or resting their heads on their arms. Some even created their own diversions by talking to themselves, singing, and inventing games with their hands and feet. One clever kid stood and traced the mortar seams in the wall with her finger. In short, delayers invented clever ways of turning aversive and boring waiting time into something that was more like a game.

When Mischel taught other children these same tactics—and thus helped them take their minds off the rewards and place them on something else—subjects routinely increased their ability to delay gratification. In similar studies where subjects were given specific tasks that would help them earn their long-term rewards, subjects who focused on the tasks as opposed to the rewards delayed longer. In contrast, individuals who glanced at the reward the most often were the least persistent. Researchers also found that distracting individuals by having them focus on the cost of failure, or thinking bad thoughts, did not enhance delay.

Finally, asking subjects to employ “willpower” by directing their attention to tasks that were difficult, aversive, or boring didn’t work. Despite the fact most people are convinced that individuals who show poor self-control merely need to exert a stronger will—demanding that subjects dig down, suck it up, or show strength of character—research found the opposite. Telling people to hunker down didn’t improve performance.

The far better strategy was to transform the difficult into the easy, the aversive into the pleasant, and the boring into the interesting. We examine methods for doing exactly this in Chapter 9 Suffice it to say that when industrial engineers began to find ways to help employees and others make their tasks easier and more pleasant, leaders learned that they didn’t have to continually harangue people to stick to their unpleasant or boring tasks. And when leaders began to learn how to measure and focus on short-term goals, it took the pressure off having to continually motivate people into hanging on until the end.

Another effective way to manage emotions is to argue with your feelings. Psychologists call this particular strategy cognitive reappraisal. When emotions come unbidden through the “go” system, they can be dragged into the light of the “know” system by activating skills only the “know” system can do. To do this, call out to your frontal lobe by asking it to solve a complex problem. That’s right. If you ask your brain to work on a question that requires more brain power than the amygdala can muster, this mental probe can help kick in the know system and restore normal thought.

To start the reappraisal process, distance yourself from your need by labeling it. (I have a craving for a cream-cheese-covered bagel. Bad.) Debate with yourself about it by introducing competing thoughts or goals (What I really want is to be proud of myself after lunch when I write down what I ate). Distract yourself (conjure up a potent image of the feeling you have when your belt feels loose). Or delay. That’s right—the “go” system can often be outwaited.

For example, as a strategy to help obsessive-compulsives cope with their tendencies, therapists teach them to wait 15 minutes before giving in to a maddening mental demand—such as washing their soap-worn hands for the hundredth time in eight hours. In the moment, we often believe that our emotions will not subside until they’re satisfied. This turns out not to be true. If you delay your urge, within a fairly short period of time the brain returns control to the “know” system, and different choices become easier.

Active strategies such as classifying, debating, deliberating, and delaying can help change what you think. They do so by changing where you think. Your “know” system starts to kick in, and you transfer control from the amygdala to the frontal lobe. Once you change where you think, you change how you think, which in turn changes what you think. You’re now able to carefully contemplate, ruminate, and take a longer-term view.

So, if, like Henry, you find yourself obsessing over the possibility of gorging yourself on chocolate—or maybe gambling or spending obsessively to the point where you can scarcely think straight—realize that there’s a set of skills you can call into play if you want to take control of your urges.

SUMMARY: PERSONAL ABILITY

When it comes to complex tasks that matter a great deal to you in your quest to resolve persistent problems, don’t suffer from arrested development. Demand more from yourself than the achievement levels you reach after minimal effort. Instead, set aside time to study and practice new and more vital behaviors. Devote attention to clear, specific, and repeatable actions. Ensure that the actions you’re pursuing are both recognizable and replicable. Then seek outside help. Insist on immediate feedback against clear standards. Break tasks into discrete actions, set goals for each, practice within a low-risk environment, and build in recovery strategies. Finally, make sure that you apply the same deliberate practice tactics to physical, intellectual, and even complex social skills. Many of the vital behaviors required to solve profound and persistent problems demand advanced interpersonal problem-solving skills that can be mastered only through well-researched, deliberate practice.

With instinctive demands and quick emotional reactions, don’t let the “go” system take control from your “know” system unless you’re facing a legitimate risk to life and limb. To regain emotional control over your genetically wired responses, take the focus off your instinctive objective by carefully attending to distraction activities. Where possible, completely avoid the battle to delay gratification by making the difficult easy, the averse pleasant, and the boring interesting. When strong emotions take over because you’ve drawn harsh, negative conclusions about others, reappraise the situation by asking yourself complex questions that force your frontal lobe to wrest control away from the amygdala.

Remember the good news here. Overcoming habits or developing complex athletic, intellectual, and interpersonal skills are not merely functions of motivation, personality traits, or even character. They all tie back to ability. Develop greater proficiency at deliberate practice as well as the ability to manage your emotions, and you significantly increase the chances for turning vital behaviors into vital habits.