Chapter 16

Understanding How Lawsuits Work

In This Chapter

Considering pre-suit issues

Preparing and filing the paperwork for your lawsuit

Getting a judgment against the debtor

Handling a contested lawsuit

Getting ready to go to court

What’s the strongest way to express your dissatisfaction over a debtor not paying a bill? How do you pull out all the stops and enforce collection of an unpaid balance? You file a lawsuit, obtain a judgment, and then enforce that judgment.

Though some lawyers tell you that the process of litigating a case is beyond the scope of what a layperson can do, the fact is that you can learn the process of suing and enforcing judgments. And with that knowledge, you may be able to do part or all of it yourself. This chapter guides you through process of litigation against a debtor, from the initial filing right up through the entry of a judgment. You may need some help along the way, but we present these materials in enough detail to get you through a simple collections suit. (For more on taking a suit to trial, check out Chapters 17 and 18.)

Knowing What Lawsuits Entail

According to the dictionary, a lawsuit is a case you file in a court, alleging that somebody has caused you harm and asking for a legal remedy. From your perspective as a credit and collections professional, a lawsuit is the strongest measure you can take to enforce collection of an unpaid balance. It involves filing a summons and a complaint with the court; the defendant/debtor then has some options, such as:

![]() Contesting your case by filing an answer and perhaps also a counterclaim against you. (See the templates provided on your CD as Forms 16-3 and 16-4). The section “Understanding the defendant’s answer to the complaint” later in this chapter discusses answers and counterclaims in more detail.

Contesting your case by filing an answer and perhaps also a counterclaim against you. (See the templates provided on your CD as Forms 16-3 and 16-4). The section “Understanding the defendant’s answer to the complaint” later in this chapter discusses answers and counterclaims in more detail.

Making arrangements for payment, which when complete results in a dismissal of the case (Form 16-5 on your CD) or entering into a settlement agreement (Form 16-8 on the CD).

Ignoring the lawsuit, which results in the court entering a default judgment in your favor. (A sample default judgment appears on your CD, as Form 16-6. The court you’re in may offer a standard form for a default judgment, and if so you should use the standard form instead.) A typical lawsuit progresses as follows:

1. You select a court to file your lawsuit in. Chapter 17 describes how to select a court, as well as factors that influence that decision.

2. You file legal pleadings, written documents formally stating a legal claim. Specifically, you file a summons and a complaint (along with the required filing fee) with the civil clerk, a process we describe in “Drawing up the paperwork” later in this chapter.

3. The civil clerk of the court issues the summons, filling in a case number and a few other details, and either returns it to you to serve on the defendant or turns it over to its own process server (a person authorized to serve court papers) to be formally served. Check out “Serving a Lawsuit: Taking the Suit to the Debtor/Defendant” later in this chapter for more details.

4. After the defendant has been served, one of two things happens.

• The defendant files an answer, placing the case at issue. The clerk then sets the matter for a hearing (see “Dealing with a Contested Lawsuit” later in this chapter for a description of this process).

• The defendant doesn’t file an answer (or other acceptable response) with the court, and you ask the court to enter a default judgment in your favor. Head to “Obtaining a Judgment by Default” later in this chapter for more on these proceedings.

5. After the period for filing an appeal (usually 28 days) expires, the judgment becomes final, and you may proceed with postjudgment collections as detailed in Chapter 19. And take a look at Chapter 12 for tips on locating assets of the defendant’s that you may be able to attach to satisfy the judgment

If a defendant answers your complaint but is unwilling to settle, a trial is held, followed by an entry of a judgment by the court. If you win, your judgment will describe the specific amount of money the defendant owes you and establish your legal right to collect that money from him.

Furthermore, your judgment accrues interest at a rate defined by the laws of your state. Translation: The longer the defendant takes to pay, the more money you get. You have the opportunity to enforce the judgment, using the tools and techniques described in Chapter 19.

Considering Case Complexity and Cost

When you choose whether to handle a case yourself, two factors usually dominate your decision-making process:

Cost: How much will it cost to litigate your case, with or without a lawyer?

Complexity: Is the case too difficult or too time-consuming to handle yourself?

Ideally, before you file your case, you should have a pretty good handle on the cost of getting a judgment and whether the case is simple enough for you to handle without a lawyer. At a superficial level, the question of cost seems easy, but cost increases with the complexity of a case. The following sections detail how these considerations affect how you decide to handle your case.

Deciding whether to hire a lawyer

What do you call the person who passes the bar exam with the lowest possible score? A lawyer. If he can learn how to try a case, so can you. In fact, you can handle a collection lawsuit yourself in many instances. Whether you file your lawsuit in small claims court or in a regular trial court (see discussion of the types of court in Chapter 17), you may choose to proceed without a lawyer if the issues aren’t too complicated (such as a small claims case, described in Chapter 18) and you’re comfortable with court procedures.

Some courts use a lot of jargon and tricky language in some of their required court forms, but don’t let that deter you. Although you inevitably encounter a learning curve, you can learn the ropes and may even discover that you enjoy the challenge of litigating. And if you find that the case becomes complicated (or you’re overwhelmed by unfamiliar jargon), you’re free to hire an attorney.

Sometimes you may want to bring in a lawyer from the start, or after developments suddenly make your case more complex. You should consider hiring a lawyer in the following situations:

The defendant files a counterclaim lawsuit against your company or persons within your company, asking for an award of damages against you, your company, or those named individuals. See “Dealing with a Contested Lawsuit (You Can Do This)” later in this chapter.

The defendant files a cross claim bringing additional parties into the lawsuit.

The defendant brings up complex issues you aren’t totally comfortable handling yourself.

The defendant hires an attorney. Battling a lawsuit where the defendant is represented by an attorney and you’re not can feel kind of like playing a pick-up basketball game against the Harlem Globetrotters.

You can’t afford to lose. Even if you think the case is really simple, when the stakes are great you may want the extra assurance.

Looking at costs and fees (both with and without an attorney)

Filing a lawsuit by yourself, particularly in small claims court, is relatively inexpensive. In most instances, you can spend $100 or less to file your case and have it served. Your local small claims court can fill you in on the costs, which typically consist of a filing fee, a service fee (to have a court officer serve your lawsuit on the defendant), and possibly some kind of hearing fee or trial fee. Some small claims courts may require that your case go through an alternative dispute resolution process (described in Chapter 15), which can increase your costs a bit.

Some lawsuits cost more than others. Factors that make a lawsuit more expensive include

The amount of money you’re seeking: The more money you claim in your lawsuit, the more expensive your filing fee is likely to be. Most states have a progression of filing fees, with fees jumping up after your claim passes a specific dollar amount.

The type of case you’re filing: Landlord–tenant matters may have a different filing fee schedule in your state courts. In addition to the filing fee for your eviction case, you may have to pay an additional fee to make a claim for a money judgment if you seek damages for unpaid rent or damages caused by a tenant.

The complexity of your case: Complicated legal actions generally cost more than simple collection cases. They often involve larger amounts of money, include multiple defendants, and require formal pretrial proceedings. One or more of the parties to a complex case is also more likely to hire a lawyer. (See the preceding section for more on deciding when to hire an attorney.) You avoid a lot of expense in attorney fees if you can handle your lawsuit yourself. Collection lawyers usually handle cases on a contingency fee, where you pay the court costs and pay the lawyer a fee consisting of a percentage of the money they recover for you. In some cases, a lawyer requires a non-contingent suit fee, a sum of money you pay her upfront in case the suit goes badly and she doesn’t end up earning a contingency fee.

Squaring Away Your Suit with the Court

You want to sue your debtor, but how do you go about filing a lawsuit? That depends on what kind of court you file in (see Chapter 17 for more on making that decision). Small claims courts usually offer simple forms for you to fill out and file; regular trial courts make things more complicated. Filing a lawsuit can seem overwhelming the first time you do it, but after you know the steps (probably the second time around), you’ll find it much easier.

The following sections walk you through the process of getting your suit in order with the court.

Drawing up the paperwork

Of course, any lawsuit involves filling out some kind of paperwork. Your lawsuit consists of a summons and complaint, backed up with exhibits such as an affidavit of account and copies of unpaid invoices. Here’s a breakdown:

The summons: The summons notifies the defendant that the you’re suing him and provides basic information such as the court location, court telephone number, case number, and your name and phone number. It also states how much time the defendant has to file an answer to your complaint (typically 28 days).

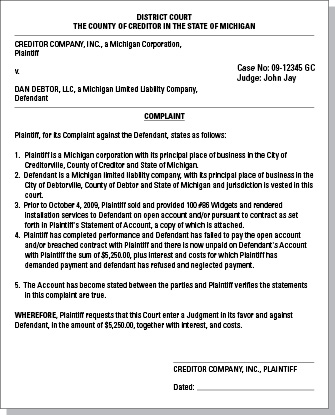

The complaint: The complaint informs the defendant of your cause of action (your specific factual and legal claims) and concludes with a request for money damages. A collection complaint is often only three or four paragraphs long, particularly when a creditor is suing on an unpaid account. Figure 16-1 shows an example collection complaint.

The exhibits: You also attach relevant exhibits to the complaint, such as the invoices and a statement showing the outstanding balance, delivery receipts showing that the goods were delivered, and the credit application and any contract involved, especially if either one of those documents establishes your right to collect interest or the costs of collection.

If you make a mistake when preparing your lawsuit, such as stating the wrong amount of money or misspelling the name of defendant, quickly file an amended complaint, making the corrections. In most courts, you may file an amended complaint before the other party is served, or within a narrow window of time (such as 14 days) after you’re served with the defendant’s answer. Rules vary by state and also by court, so check the court rules to see what specific time limits apply in your court and when you must get the court’s permission before you can amend your complaint. A sample motion to amend a complaint is provided on the CD as Form 16-24.

Filing your lawsuit with the court

If you’re representing yourself, your best bet is to hand-carry your first lawsuit to the court instead of shoving it into an envelope and trying to file it by mail. If you go to the court in person, you can talk to the civil clerk when you file your case, find out immediately whether you’ve made a mistake, and ask questions about court procedure or recommended process servers. The court clerk can’t give you legal advice, but she can provide a lot of information about court forms, filing documents, and court procedures.

Figure 16-1: A collection complaint.

In most courts, the process of filing a lawsuit works like this:

1. Take your prepared summons, complaint, and exhibits to the court.

Have at least three copies of your complaint and exhibits, one for the court, one for yourself, and one for the defendant. If your case involves more than one defendant, take along another complete set of paperwork for each additional defendant.

Take two copies of the summons for each defendant, in addition to a copy for the court and one for your own file. The summons is normally prepared on an official court form and usually includes a “proof of service” on the back of the form for your process server to complete. Your process server leaves one copy with each defendant and files the other copy with a completed proof of service to the court. (See the preceding section for more on these forms.)

2. Give the documents to a court clerk to get a case number.

The clerk assigns a case number to your case and then stamps the summons and complaint with that case number.

![]() All documents you file in your case must include the case number — that’s how courts keep track of the documents for your case. Some courts use sticky labels to add case numbers to documents. If your court uses labels, you should use them on all documents you file (and get some labels to use on future filings). Otherwise, write the number clearly on all the copies of the summons and all copies of the complaint.

All documents you file in your case must include the case number — that’s how courts keep track of the documents for your case. Some courts use sticky labels to add case numbers to documents. If your court uses labels, you should use them on all documents you file (and get some labels to use on future filings). Otherwise, write the number clearly on all the copies of the summons and all copies of the complaint.

3. If the court has its own process server, leave the defendants’ copies of the lawsuit with the court clerk.

The court server takes care of serving the defendant with the suit; otherwise, you have to serve it yourself. Head to “Serving a Lawsuit: Taking the Suit to the Debtor/Defendant” later in this chapter for more on serving your lawsuit.

Paying the necessary fees

To start your lawsuit, you have to pay some fees:

Filing fee: When you file your case, the civil clerk of the court tells you the exact amount of money you must pay to file your lawsuit. The cost of filing a lawsuit usually depends upon the amount of money you seek to recover from the defendant. Keep in mind that many courts don’t accept personal checks.

Service fee: This fee is the amount paid to a process server to hand a copy of the summons and complaint to the defendant.

The exact fees and amounts you have to pay vary by court, so check in with your local court for more details. Also keep in mind that you may have to pay other sorts of fees (such as motion fees, case evaluation fees, or judgment fees, among others) as your case progresses.

Serving a Lawsuit

The law requires that you serve the defendant with legal papers in such a way that you can later prove that the defendant actually received them. This process is sometimes easier said than done when your defendant dodges all attempts to give him the papers. This section shows you some options for ensuring that your paperwork gets served so that your case can proceed.

Ensuring your lawsuit is properly served

After you get a default judgment against a defendant who never responded to your suit, the defendant often complains that she didn’t even know she was being sued. You can avoid and overcome claims of non-service by making sure that your lawsuit is properly served.

A good way to cover all your serving bases is to make three copies of the summons, complaint, and exhibits for each defendant in the case and then serve each of your defendants in three separate ways:

Service by regular mail: Send a copy of the paperwork to each defendant by regular first-class mail.

Service by certified mail: Send another copy of the documents to each defendant by certified mail and request a return receipt. Use restricted delivery, instructing that your letter may be delivered only to the defendant. Keep the certified mail card when it comes back from the post office; this slip is crucial because it contains the defendant’s signature and proves that he received and signed for the certified mail.

Service by a process server: For each defendant, you give a copy of all the forms to a process server, along with an extra copy of the summons. The process server hand-delivers a copy of the documents to the defendant and then completes a proof of service (indicating that she did in fact serve the papers) on the second copy of the summons and files it with the court. The court may have its own server, or you can get your own. See the following “Hiring a process server” section for more on going this route.

After service is complete, you should also file a proof of service with the court describing how you served the defendant (by mail, by process server, and so on).

Hiring a process server

In some states, a party to the lawsuit (one of the plaintiffs, also known as you) isn’t permitted to serve process upon the defendant, but even if that’s allowed you’re better off using a third-party process server. At first blush, you may think that anyone can be a process server (how hard is it to hand someone a bunch of papers?), but the responsibility is much greater than that. Check the court rules to see who may permissibly serve your documents. You can ask the court clerk whether the court maintains a list of approved or recommended process servers. If you’re lucky, the court has a process server, and you don’t have to worry about finding and hiring your own. But if not, you must exercise care in selecting your process server.

You generally want to stick with a professional despite the fee (which usually isn’t even that bad). Most process servers are responsible and ethical, but a few engage in what’s known as gutter service, figuratively (or literally) tossing your documents in the gutter, submitting a false proof of service to the court claiming to have served the defendant, and sending you a bill.

Plus, if the defendant denies being served, you want your process server to be somebody the court can believe. Your process server may end up testifying in court about how she made service, and you need the judge to believe the testimony. Feel out the process server’s reputation in the local legal community, or get references from the court clerk, lawyers, or collections professionals.

Serving the suit to a hiding defendant

What happens if you just can’t get your defendant served? Mail comes back marked “return to sender” (or “address unknown,” or “no such number”). The defendant refuses to sign for certified letters. Your process server can’t find the defendant, or reports that she’s hiding, keeping the lights out at home, is always absent from her place of business. You have to get those documents served in order to move forward, right?

Not necessarily. The court can grant you an order for alternate service, also called substituted service. After hearing evidence about why the defendant can’t be served by conventional means, the court may authorize you to serve the defendant through public postings, service on the defendant’s last known address, publication of a legal notice in the newspaper, or some combination of methods that the court believes is reasonably likely to provide the defendant with notice that she’s been sued.

After service: What happens next

After you file your lawsuit, the suit goes in one of two directions:

The fast track: The fast track occurs when the defendant doesn’t file an answer and you can take a quick default judgment.

The slow track: The slow track occurs when the defendant does file an answer and the process goes through a series of hearings and possibly even a trial.

Figure 16-2 provides a timeline of how lawsuits are resolved, both on the fast track and on the slow track.

Service of the summons and complaint usually takes between 10 and 90 days (see the preceding section for more on serving the lawsuit). If the defendant fails to answer in the amount of time indicated by the summons (see “Drawing up the paperwork” earlier in this chapter), you can put the case on the fast track by requesting that a default judgment be entered.

Obtaining a Judgment by Default

After you’ve served the summons and complaint on the defendant, you should be able to request a default judgment against the defendant if the period of time for her to answer your complaint (typically 28 days) passes without her filing an answer. Depending on your court, this process may have up to three parts:

Filing a default: You file a document with the court confirming that the defendant hasn’t served you with an answer and requesting that a default be entered.

Getting a default judgment: The court confirms whether an answer is on file with the court; if no answer is on record, the court grants the default judgment.

Holding a hearing on damages: This step is probably not necessary if you’ve requested a specific dollar figure in damages. If the court needs to determine the amount of damages to be paid, it does so at a hearing. The defendant is entitled to notice of the hearing and to appear and participate.

Figure 16-2: Diagram of a lawsuit.

When you petition for a default judgment, many courts require that you file two separate documents: a default and a default judgment. The court may have standard forms for you to use. You can check with the court clerk to confirm local procedures and to find out whether forms are available.

Prepare the default entry and the default judgment by filling in the blanks, updating the amount of interest due and the total amount of your court costs. Submit the documents to the civil clerk of the court, either by mail or by hand delivery, along with any fee for the entry of a default judgment.

After a default judgment has been entered against your defendant (or defendants), you must wait until the appeal period expires (typically another 28 days) before you may take action to collect the amount owed. After the appeals period expires, you may use postjudgment collection tools such as execution, garnishment, creditor’s exam, and so forth. We’ve got you covered there. The full post-judgment collection process is discussed in detail in Chapter 19.

Dealing with a Contested Lawsuit (You Can Do This)

If the defendant files an answer to your lawsuit, the court clerk places the case on the court’s trial docket. You receive a copy of the answer either from the civil clerk or directly from the defendant.

Understanding the defendant’s answer to the complaint

The defendant’s answer should follow along with the complaint. In other words, if the defendant has filed a proper answer, each paragraph of the answer corresponds to a paragraph of your complaint. Although the defendant may add some factual claims or vary a bit from the standard, most responses are pretty simple:

Admitted: The defendant admits a particular claim is true.

Denied: The defendant denies the claim, asserting that it’s not true.

Neither admitted nor denied for lack of information, knowledge or belief as to the truth of the matter asserted: How’s that for a mouthful? That type of answer is a dressed-up way of saying “I don’t know.”

For example, if in paragraph one of your complaint you state “Defendant purchased 2,000 blue widgets at $1 each” the defendant is likely to reply either “admitted,” conceding that he did make the purchase, or “denied,” asserting that he didn’t make the purchase. In this case, the defendant probably won’t claim not to know whether he made the purchase; unless he has amnesia, there’s no good reason why he shouldn’t know.

If in your next paragraph you assert, “The plaintiff’s accounts show that the defendant owes $2,000,” the defendant may take that third option, answering “Neither admitted nor denied, as the defendant has no information, knowledge, or belief as to what’s in the plaintiff’s accounts.” (You’re more likely to get a direct admission or denial if you instead state, “The defendant owes the plaintiff $2,000.”)

Sometimes the defendant may respond to one of your assertions by breaking it into parts and separately addressing each part. For example, if you allege “The defendant purchased 2,000 blue widgets from us at $1 per widget, and now owes $2,000,” the defendant may answer, “Admitted that the defendant purchased 2,000 widgets; denied that the defendant owes the plaintiff money.”

Read the answer carefully so that you can determine the defendant’s specific objections. Sometimes the defendant admits that the entire debt is owed and simply wants time to pay it. Other times, the defendant may offer minor denials such as denying that one invoice is unpaid when you’ve sued over twenty. If she’s admitting most of the amount you’re claiming, consider waiving the difference and entering a settlement or seeking a judgment for the amount she admits is due.

Some defendants deny to the point of absurdity. They deny their address, the locations where they do business, and even their name. That behavior suggests the defendant is going to be difficult to work with in court. Fortunately for you, judges usually recognize when a defendant is in deny-everything mode, and that can work to your advantage if it paints you as the reasonable party.

Affirmative defenses

In addition to answering your complaint, the defendant may raise affirmative defenses, claims that if true overcome the defendant’s obligation to pay you. Affirmative defenses are normally stated after the answer, sometimes in a separate document. The term affirmative refers to the fact that the defendant raising an affirmative defense has the burden of proving that defense. The most common affirmative defenses include claims by the defendant of

Payment: The amounts you claim have already been paid.

Satisfaction: The dispute has been resolved through your acceptance of an amount less than what you claim is owed. This defense is sometimes called accord and satisfaction.

Discharge: The amount claimed has been discharged in bankruptcy.

Release: You entered into a contract that releases the defendant of any obligation for the amounts you claim, for example when you and the defendant signed a release agreement to resolve a prior lawsuit.

Fraud: The amount claimed is based upon an act of fraud by you (such as your billing for goods you know you haven’t delivered) and is thus not recoverable.

Statute of limitations: You waited too long to file your lawsuit, and the law now prevents you from recovering the money.

Void agreement: The contract was totally contrary to law.

Failure of consideration: A situation arises after the contract’s creation that alters the rights of the parties and deprives one side of the benefit of the deal. For example, your right to collect the purchase price for goods you sell depends on those goods not being defective. If you provide defective goods, you haven’t provided anything of value so your customer can rightfully withhold payment on the basis of failure of consideration.

Depending on your state’s rules of procedure, you may be required to file an answer to the defendant’s affirmative defenses. If you don’t know whether you must respond with a separate pleading, ask the civil clerk (keeping in mind that not all are willing to answer this type of question) or an attorney familiar with litigation in the same court.

Counterclaims

Sometimes a defendant files a counterclaim (a lawsuit by the defendant against you, the plaintiff). You absolutely must defend against the counterclaim by filing an answer within the prescribed period of time, usually 28 days.

What’s the defendant alleging in the counterclaim? Did your simple collection case just get complicated? When faced with a counterclaim, many do-it-yourselfers consult a lawyer for help with the issues or have a lawyer take over the case.

The discovery stage: Asking questions of the defendant before trial

In regular trial courts, most courts schedule a period of time for the parties to engage in discovery, the formal exchange of information and evidence. Typical forms of discovery include

Interrogatories: Written questions that the other party is required to answer.

Request for admissions: A demand that the other party admit or deny specific facts.

Request for production of documents: Asking that the other party either provide you with copies of documents or make them available for copying. Similar discovery requests can be made to examine physical evidence or real estate.

Depositions: Questioning a witness under oath in front of a court reporter who transcribes the proceeding. Depositions can be quite costly, so use this option judiciously.

Discovery helps you avoid surprises at trial by allowing you to gather facts beforehand. The knowledge you gather can help you present your case more clearly and may help you reach a settlement without going to trial. Note: Formal discovery is usually not allowed in small claims court, although some courts have simple discovery documents you may ask the other party to complete.

Courts may limit discovery, such as by forbidding it or requiring permission to conduct discovery on cases involving smaller amounts of money. Ask a civil clerk or an attorney familiar with litigation in that particular court about how it conducts discovery. If your case is in a regular trial court, also check the court rules for the court you’re in.

When a court does allow discovery, you can use that process to seek evidence and admissions that help your case. The defendant has the same discovery rights that you have.

Filing motions in court

A motion is a formal request for the court to take action. Note that motions usually aren’t allowed in small claims court. The following sections give you the skinny on your various motion options and how to file them.

Different motions to file

You normally submit motions in writing before the trial, often backed up by a brief that expands upon legal issues you’re asking the court to decide. Motions can focus on issues of fact (for example, whether the signature on a contract is in fact that of the defendant) or issues of law (for example, whether a clause of a contract is legally enforceable). When an issue of law is the focus, the court rules usually require a brief. You or your opponent may file a motion for many different purposes. Examples of motions include

Motion for change of venue: A motion by the defendant asking the court to declare that you should have filed the lawsuit somewhere else. In criminal cases, change of venue motions are usually based on negative pretrial publicity, but that’s a claim rarely made in civil cases. Instead, civil arguments tend to revolve around the proper interpretation of the statutes that define proper venue, or claims that litigating in the location where the case was filed would be unduly burdensome to the defendant. Chapter 17 tells you how to determine proper venue for your lawsuit.

Motion to dismiss: A motion by either party asking the court to dismiss the lawsuit/counterclaim.

Motion for summary judgment: A motion by either party asking the court to declare that that party is entitled to prevail in the lawsuit (or part of the lawsuit) as a matter of law. For example, if the defendant admits most of your allegations, you may file a motion for summary judgment against the defendant asking that the admissions provide a legally sufficient basis for the court to rule that the defendant owes the money you claim in your lawsuit.

Motion in limine (lim-in-nee): A motion asking the court to rule on the admissibility of evidence before trial.

Filing and answering motions

Filing a motion with a court typically follows the following steps:

1. Compose a written motion and, if desired or required by the court, a brief supporting your motion.

2. Contact the court to ask which days it hears the type of motion you’re filing and to confirm that it has room on its docket on the day you choose.

Some courts prefer to schedule their own hearing dates after you file your motion.

3. Prepare your motion for filing:

• Create a notice of hearing describing the exact date and time that the motion hearing is to take place. The court may have a standard notice of hearing form for you to use, possibly combined with a praecipe (see the following bullet).

• Fill out a praecipe (preh-suh-pee), a document traditionally used by courts to schedule cases and manage the docket.

• Make copies of your motion (and brief, if you wrote one — see the preceding section) for filing. Some courts require a hand-signed original and may also require a copy for the judge. When you file the motion, ask whether the clerk can put the judge’s copy in his mailbox or whether you should take it to his chambers.

Procedures for scheduling and filing motions vary widely from court to court, so be sure to find out your court’s procedures and any forms it requires or prefers you use when filing your motion. Court clerks are usually quite helpful at explaining how to file a motion.

4. Prepare a proof of service describing how and when you provided a copy of your motion and other documents (such as the notice of hearing and praecipe) to the defendant.

![]() An example proof of service is provided on the CD as Form 16-25.

An example proof of service is provided on the CD as Form 16-25.

5. Go to court on the scheduled day and argue your case.

Be there on time!

What if your case involves three or more parties? Regardless of whether the motion is addressed to them, serve copies on everybody.

Answering a motion is a lot less complicated. You prepare your answer, a brief in support of your answer (if you choose or if required by the court), and a proof of service; serve the documents on the court and opposing party just as you file a motion; and appear in court on time to argue your side.

Talking to the Judge before Trial

If you read a lot courtroom fiction or watch lawyer shows on TV, you may have heard about ex parte communication, and that it’s prohibited. In a contested case, one where a defendant has shown up (there’s no ex parte communication concerned where a defendant hasn’t appeared) to answer the plaintiff’s complaint, communication with a judge is ex parte when either the plaintiff or the defendant isn’t included in the conversation. But pretrial conversations can occur with the judge when both parties participate, and both sides have the opportunity to talk to the judge and hear what the other side has to say.

As a matter of routine before trial, a judge in a regular trial court schedules some type of hearing, probably called a pretrial conference or settlement conference. The judge may schedule a pretrial conference to try to resolve the matter so that the case doesn’t have to go to trial.

A pretrial conference may focus on scheduling events in your case, such as when you must exchange witness and exhibit lists, when discovery may be conducted, when (or whether) you want to go through alternative dispute resolution before trial, and how long a trial is expected to last. Hearings focusing on scheduling and the progress of your case may also be called status hearings.

A settlement conference gets the parties together to try to resolve the case without the need for a trial (and judges can put a lot of pressure on you to settle). You should anticipate questions that probe (and perhaps exaggerate) any weaknesses in your case. The court may

Meet with the parties together in chambers (in the judge’s office) to try to help them reach a settlement

Provide the parties with a conference room where they can meet privately to try to work out their differences

If you end up in settlement negotiations, follow the procedures in Chapter 9 for negotiating a settlement and then enter a written settlement agreement or a judgment as described in Chapter 10.

These two kinds of hearings aren’t mutually exclusive. Within a single hearing, the court may attempt to settle the case or get a sense for the likelihood of settlement, and then schedule future events based upon whether or not the case is likely to settle.

Going to Trial

If your case doesn’t settle, the judge sets it for trial. Your trial can take one of two forms:

Bench trial: You try the case before a judge alone. All arguments are addressed to the judge, who makes all decisions, both of law and fact. At the conclusion of the case, the judge makes a decision, often supported by a document formally reciting his findings of fact and conclusions of law. A bench trial is also called a non-jury trial.

Jury trial: In a jury trial, the judge decides questions of law, such as deciding the parties’ motions and resolving objections to questions or evidence, and instructs the jury about what the law means. The jury decides the facts and, at the end of the trial, renders a decision.

Juries aren’t available in small claims court, but for most other cases you can to go trial with or without a jury. Generally speaking, you must formally request a jury in your complaint and pay a jury fee when you file your complaint. You may be able to request a jury later, but make sure you know the deadline. If you don’t request a jury for a matter eligible to be tried by a jury, the defendant can request one. Keep in mind that jury trials are more complex to handle than bench trials. If you’re considering requesting a trial by jury or if the defendant demands a jury, you may benefit from consulting or hiring a lawyer.

If no party requests a jury, your case is scheduled for a bench trial. The court may still appoint a jury, but that rarely happens. (But I do know a judge who always appoints a jury regardless of whether any of the parties want one.) The trial process is fully described in Chapter 18.

If you request a jury trial, the court expects you to provide proposed jury instructions, the information the judge presents to the jury explaining the law and what the parties must prove in order to prevail in the case. Typical instructions in a collection case inform the jury about contracts and collection law so that after the trial is over they can make an informed determination of whether a contract existed and whether it was breached.

Know the expectations of the court, particularly if you’re in a regular trial court. A regular trial court may expect you to file a lot of documents:

You’ll most likely have to file witness and exhibit lists and other documents (such as the aforementioned jury instructions) well before trial.

The court may request a trial brief, basically a summary of the facts of your case and the law you intend to rely on in court.

After a bench trial, the court may ask you to submit findings of fact and conclusions of law, describing the conclusions you want the court to reach regarding what happened and why your side should win under the law.

In small claims court, procedures are simplified, and you should feel comfortable and confident presenting your case as a witness. (Chapter 18 guides you through your role as a witness and how to present a case in court.) To read about how small claims cases proceed in your state and county, get a copy of the small claims brochure for your court (most courts have them) or check the court Web site to see whether you can get the information online. If the matter is rather complicated you may benefit from consulting or hiring an attorney.

Filing an Appeal

What if you lose? If you’re not satisfied with the final outcome of the trial, you can appeal. A few small claims courts don’t permit appeal, but pretty much every other court gives you the right to appeal the verdict.

Chapter 17 describes the appellate process. Taking on an appeal can be daunting. It requires filing paperwork on certain time lines, paying a filing fee, and preparing a complex appellate brief. For most appeals, you probably want to hire a lawyer.