Questionnaire Design

Below, you will find Part II of the Infinity Insurance Case Study. This section of the Case Study includes several concepts from the current chapter, and is meant to provide a real-world example of the processes outlined in this text. As you read along, consider some of the “Food for Thought” questions and decide for yourself how one might answer these questions. If desired, you may compare your answers with the “Possible Answers” section at the end of the chapter that was developed while working with Infinity Insurance, keeping in mind there are multiple ways of answering each question.

Infinity Auto Insurance—Administering a Survey

Part II—Infinity Case Study

After identifying the required sample size, and the number and types of questions that could help Infinity Insurance better understand their market, the researcher must then determine the most effective way to acquire this information. Researchers must balance using a sound survey methodology with the practical constraints under which business research often operates. That is, how can you implement the best practices outlined in this book, while simultaneously operating within the financial, logistical, and practical realities of conducting survey research?

Infinity Insurance wanted to specifically target less-acculturated Hispanics and Millennial Hispanics. It was decided that a telephone survey would best reach the less-acculturated Hispanic population. To access the Millennial Hispanic population, on the other hand, it was decided that an electronic, web-based survey would be best. Outlined below are considerations to make to arrive at a practical, scientific, and methodologically rigorous approach to help Infinity Insurance better understand their market. Responses to these considerations are provided at the end of this chapter.

Food for Thought:

- If you were working for Infinity Insurance, how would you go about gathering a valid sample?

- What type of survey administration might be most beneficial? (e.g., online, telephone, mixed mode, etc.)

- Should you incorporate incentives into the survey?

- Should you pilot the survey?

- What issues would help create, or hinder you from creating a statistically valid sample?

This chapter provides a framework for effective questionnaire design. All statistical analyses require high-quality data input. The first step in collecting unbiased, reliable, and valid survey data is having an unbiased, reliable, and valid survey instrument. Outlined below are the major decisions that must be made during the survey design process. Throughout the chapter, we will discuss several examples of effective survey design, as well as some of the more common pitfalls to avoid.

Major Decisions on Questionnaire Design:

- What should be asked?

- How should each question be phrased?

- In what sequence should questions be arranged?

- What questionnaire layout will best serve the research objectives?

- How should the questionnaire be pretested? Does the questionnaire need to be revised?

A Survey Is Only as Good as the Questions It Asks

Because questions are the main component of any survey, learning how to ask questions in both written and spoken form is essential. A survey researcher’s goal is to create a clear, concise, and straightforward question which communicates the desired information and the desired format for a response. These unambiguous questions should, in turn, extract accurate and consistent information from respondents. The best survey questions are purposeful, use correct grammar and syntax, and call for a response on one construct at a time (i.e., questions should be mutually exclusive).

The specific questions that will be asked are a function of the survey objectives, the type of information the researcher would like to collect, and the constraints under which the research must be conducted. The later stages of the research process will have an important impact on the wording of the questionnaire. When designing the questionnaire, the researcher must also consider what types of statistical analyses will be conducted, since the wording and format of survey questions can limit the types of statistical analyses that can be performed. The most obvious example is the difference between qualitative and quantitative questions; however, a more complex example includes whether one can interpret the statistical or numerical meaning of a bipolar scale that has positive and negative response options.

The design of your questionnaire is one of the most critical stages in the survey research process. Unfortunately, new survey researchers who do not yet know the complexity of survey design, learn the hard way that common sense and good grammar are not the only determinants of an effective questionnaire.

Where Do Survey Objectives Originate?

Survey objectives often originate from a defined need. For example, suppose a company is interested in determining the causes of workplace dissatisfaction in their sales department. The company calls on the Human Resources Department to design and implement a survey of its employees. The objective of the survey (i.e., to find out why sales associates are less engaged at work) is defined for the surveyors and is based on the company’s needs.

The objectives of a survey can also come from a review of both existing literature and previously administered surveys. Here, existing literature refers to all published and unpublished public reports on a topic. These reports can come from academic journals, business magazines, doctoral dissertations, and so on. A systematic review of existing literature can help you better understand what is currently known about a topic or construct. This can either serve as a foundation for your current survey, or can help you identify gaps in the literature that you may want to investigate.

The objectives of a survey can also originate from interactions/conversations with other experts. Two types of meetings that often give rise to new survey objectives, research questions, and research hypotheses are focus groups and consensus panels. A focus group typically consists of 8 to 10 people. Among them is a trained leader who conducts a carefully planned discussion and cultivates an open and nonjudgmental atmosphere to obtain participants’ honest opinions on a topic of interest.

A consensus panel, on the other hand, may contain up to 10 subject matter experts (SMEs) and is intended for larger organizations. If you are conducting a consensus panel, you should ensure the panel is led by a skilled leader (or moderator) in a highly structured setting. The trained leader ensures important techniques on group dynamics are used, which encourage discussion and consensus. SMEs who participate in these types of discussions are knowledgeable about the survey topic. SME’s may also be willing to contribute to the development of the survey because they may be affected by the survey’s outcomes, they may be able to implement some resulting change, or they may benefit in some other way from the study’s findings. If desired, SMEs can be surveyed by mail, telephone, or in person as a group or individually. Consensus participants, for example, may be required to read documents and rate or rank their preferences, which can be conducted in any three of these formats. Exhibit 4.1 illustrates how focus groups and consensus panels can be useful in identifying survey objectives.

Exhibit 4.1

Identifying Survey Objectives: Focus Groups and Consensus Panels

Focus Groups

A 10-member group—6 sales associates, 2 managers, and 2 HR representatives—were asked to help identify why sales associates were exhibiting a recent decrease in job engagement. The group met for two hours at an onsite location. The group was told that the overall goal of the survey was to identify which aspects of their work, their environment, and the organizational systems could be changed to increase engagement and productivity. What information should the survey collect? What types of questions should be asked in the survey? How can the sales staff be encouraged to provide honest and forthright feedback, and not just provide socially desirable answers? This survey has two main objectives:

- Identify what specific job characteristics are impacting the job engagement of sales department employees.

- Identify to what extent sales department employees feel supported by their organization, their supervisor, and their coworkers.

Consensus Panels

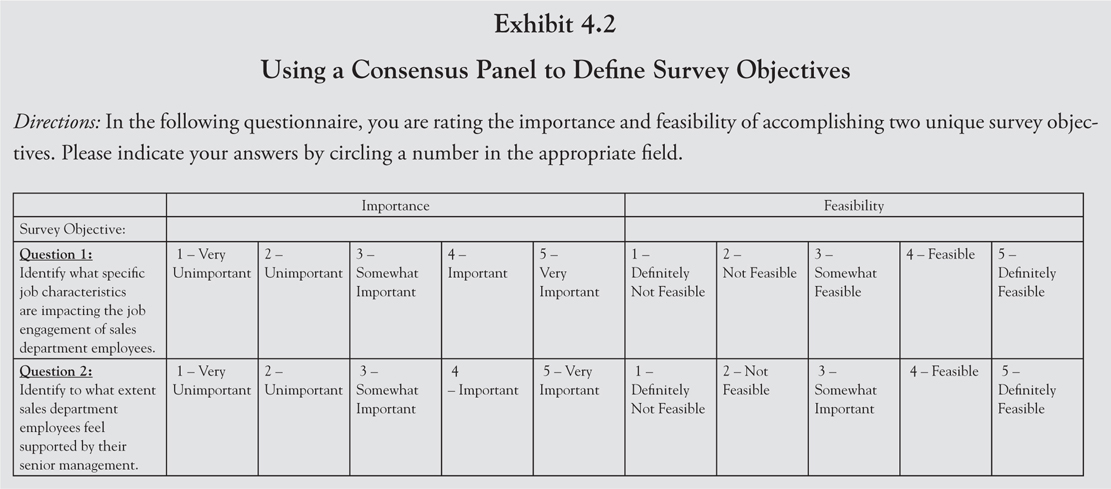

Two rounds of consensus panels were conducted to help determine the major objectives of a survey. The survey will investigate why sales associates are exhibiting a recent decrease in job engagement. The panel consisted of 10 members with expertise in survey research, organizational behavior, sales, and human resource management. In the first round, panelists were provided with a list of potential survey objectives and were asked to rate each on two dimensions: importance and the feasibility of implementing a practical solution. The data collected from the panelists were analyzed to identify objectives based on two criteria, importance and feasibility. Exhibit 4.2 shows a portion of the rating sheet.

In the second round of the consensus process, panelists met for a half-day and discussed the first round’s ratings. After their discussion, the panelists rated the objectives a second time. Objectives were chosen for the survey that at least 8 of the 10 panelists agreed were “very important” and “definitely feasible.”

While both methods can be effective in generating survey objectives, these slightly different approaches may result in different objectives. It is important to consider which method is most appropriate for your survey before deciding which to use in your organization. Focus groups are especially effective for idea generation. Gathering a group of individuals together, and implementing brainstorming techniques can help your survey more effectively gather information on broad topics from multiple perspectives. Comparatively, consensus panels can help researchers confirm the information generated during a focus group. In this instance, experts help to reinforce the accuracy, validity, and usefulness of the survey objectives generated during the focus group. These techniques can be applied independently, or in concert with one another. For example, a researcher may hold a focus group during the first half of the day, and subsequently conduct a consensus panel with outside experts during the second half of the day. This allows the individual or group conducting the survey to efficiently gather large amounts of information that can be used to generate concrete and specific survey objectives.

Survey Objectives: Identifying/Measuring Desired Outcomes

What should the survey ask? What information should it collect? You must know the survey’s objectives to answer these questions. In this instance, it is helpful to have a specific objective or a statement of the survey’s desired outcomes. Exhibit 4.3 contains three objectives for a survey investigating low levels of job engagement among sales department employees.

Exhibit 4.3

Illustrative Objectives for an Engagement Survey

- Identify what specific job characteristics are impacting the job engagement of sales department employees.

- Identify to what extent sales department employees feel supported by their organization, their supervisor, and their coworkers.

- Determine the characteristics of employees who experience the lowest levels of job engagement.

A specific set of objectives such as these suggest a survey that asks questions about the following:

- Objective 1: Impact of Job Characteristics (e.g., feedback)

- Sample survey question: Employees at Company XYZ, Inc. receive timely, specific, and actionable feedback from the organization.

- Objective 2: Perceived Organizational Support

- Sample survey question: The organization provides resources that make you feel supported at work.

- Objective 3—Part 1: Demographic Characteristics

- Sample survey question: What is your gender? What is your age? How many individuals do you report to? How many individuals report to you?

- Objective 3—Part 2: Tenure

- Sample survey question: What is your official job title? How long have you been working at Company X? How long have you been working in the sales industry?

Suppose you decide to add several additional objectives:

- Determine employee’s satisfaction with current compensation structures.

- Determine if employees are being recognized/rewarded for their work.

If you add objectives to the survey, you may need to add questions to the instrument. To collect information on the new objectives listed above, for example, you would need to ask questions regarding employees’ affective reactions to their compensation formats, perceived fairness, frequency of positive feedback, frequency of recognition for a job well done, and so on.

Designing Questions with Relevance and Accuracy

Relevance and accuracy are the two most basic criteria for a questionnaire to achieve the researcher’s purpose. A questionnaire is relevant when all the information collected is necessary and helps accomplish the survey’s objective. To ensure information relevance, the researcher must be specific about data needs—that is, there should be a rationale for each survey item. Accuracy, on the other hand, means that the information gathered is reliable and valid. It is generally believed that researchers should use simple, understandable, unbiased, unambiguous, and nonirritating words. Respondents tend to be most cooperative when the subject matter is interesting; so, if questions are lengthy, difficult to answer, or threatening in some way, the probability of acquiring biased answers is much higher.

Question Objectives

Purposeful Questions: Purposeful questions are those that are logically related to the survey’s objectives, meaning, the respondent can readily identify the relationship between the intent of the question and the objectives of the survey. Sometimes, it is necessary for the researcher to draw a connection for the respondents to help them understand why the question is relevant in the context of the survey. This is illustrated in Exhibit 4.4.

Purposeful Questions—The Relationship between the Question and the Survey’s Objectives

Survey Objective: To determine why employees in the sales department are not engaged at work.

Survey Question: How long have you been working in the sales industry?

Comment: The relationship between the objective and question is not clear. In these instances, the surveyor should place a statement just before the question that says something like:

As part of this survey, we would like to identify how experience and organizational tenure impact employee attitudes. To do this, we may need to compare responses based on individual characteristics, such as tenure. Therefore, the next five questions will ask you about your age, education, and experience.

Concrete Questions: A concrete question one that is precise and unambiguous. Questions are precise and unambiguous when, without prompting, two or more potential respondents can agree on the exact same meaning and interpretation of the same question. For example, suppose you want to examine how the relationship between an employee and their supervisor impacts their job engagement. An employee who has had generally positive interactions with their supervisor, but recently had a disagreement with them, might answer differently from another individual who has had generally negative interactions with their supervisor, but recently participated in a successful team-building exercise. To help make a question more concrete, add a specific time period:

Less Concrete: How would you describe your relationship with your supervisor?

More Concrete: In the past three months, how would you describe your relationship with your supervisor?

Detailed questions help produce more reliable answers. For example, if you are surveying affective reactions to compensation systems, decide on the components of the compensation package that are the most important to the survey, as in these examples:

Less Concrete: Do you like the way you are compensated at Company X?

More Concrete: Are the compensation structures at Company X easy to understand?

Even More Concrete: Do the incentive systems (e.g., sales bonuses/commission) at Company X motivate you to attain your sales goals?

Guidelines for Asking Survey Questions

The following section discusses guidelines for asking survey questions. You may find that for your survey, some of these guidelines are more relevant or important than others.

Types of Questions

Carefully designing survey questions is a very important step for conducting survey research. To determine the types of questions your survey requires, start by defining the survey objectives. A common pitfall survey researchers encounter is gathering inaccurate and non-essential information because they did not ask the right questions (i.e., questions that directly tie to the survey’s objectives). Another common pitfall is forgetting to ask demographic questions (e.g., tenure, seniority, age, ethnicity). Demographic information can be critical in analyzing results, as different demographic groups may be impacted by the same issue in different ways.

There are a multitude of ways to phrase your survey questions, but before creating questions from scratch, consider first the many standard formats for questions that have been developed in previous research.

Questions can first be categorized into two basic question types, based on the amount of freedom respondents are given in answering.

- Open-ended response questions are free response questions. They often pose some problem or topic and ask the respondent to answer in their own words. Open-ended questions are most beneficial when the researcher is conducting exploratory research. By gaining free and uninhibited responses, the researcher may find a trend in reactions that was unanticipated toward the project; these responses can provide a rich source of feedback. Open-ended response questions may be particularly useful at the beginning of an interview-based survey, as they allow the respondent to warm up to answering questions, and they provide an opportunity for respondents to voice their opinions. The cost of open-ended response questions is substantially higher than that of close-ended questions, since open-ended responses need to be edited for input errors or consistency, and then, coded across responses. Needless to say, analyzing open-ended response data is quite extensive, not to mention, open-ended response questions allow for potential interviewer bias. Interviewers may knowingly or unintentionally influence the respondent’s answer; even trained interviewers sometimes take shortcuts in recording answers.

- Close-ended questions, however, give respondents a specific and limited number of response options, often asking the respondent to choose the response closest to his or her viewpoint. Close-ended questions require less interviewer skill, take less time, and are easier for the respondent to answer. There are various types of close-ended questions, explained in detail below.

- Single-dichotomy or dichotomous-alternative questions require that the respondents choose one or two alternatives. The answer can be a simple “yes” or “no” or a choice between “right-handed” or “left-handed.”

- Multiple-choice question types:

- Determinant choice: These questions ask a respondent to choose one and only one response from among several possible alternatives.

- Frequency determination: These questions ask a respondent to indicate the general frequency of an occurrence.

- Likert scale: These questions ask respondents to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with a series of statements. This is one of the most widely used scale formats.

- Checklist: These questions allow respondents to provide multiple answers to a single question (e.g., check all that apply). In many cases, the choices are adjectives that describe a particular object. There should not be any overlap among categories in the checklist—each alternative should be mutually exclusive.

- The researcher should strive to ensure there are sufficient response choices for respondents; however, a continuum of categories reduces potential bias caused by respondents avoiding an extreme category.

- Respondents should select clear choices; however, they may select an alternative response among those presented. Or, as a matter of convenience, they may select a given alternative, rather than thinking of the most correct alternative. See Exhibit 4.5 for example question types.

Exhibit 4.5

Example Question Types

- Determinant Choice: Many people are using dry-cleaning less because of improved wash-and-wear clothes. How do you feel the quality of your wash-and wear clothes have affected your use of dry-cleaning facilities in the past four years?

_____ Use Less _____ No Change _____ Use More

- Likert Scale: In light of today’s savings and loan crisis, it would be in the public’s best interest to have the federal government offer low-interest, insolvent loans.

____ Strongly Agree ____ Agree ____ Uncertain

____ Disagree ____ Strongly Disagree

Most questionnaires include a mixture of open-ended and close-ended questions. Both forms have their own unique benefits, and the change of pace offered by the mixture of question types helps mitigate respondent boredom and fatigue. Exhibit 4.6 is a brief checklist to assist in deciding what types of questions to ask respondents.

General Guidelines for Asking Survey Questions

In brief, these guidelines will help improve the quality of the inferences you can draw from a survey:

- Avoid complexity; use simple, conversational language

- Avoid leading and loaded questions

- Avoid ambiguity; be as specific as possible

- Avoid double-barreled items

- Avoid making assumptions

In developing a questionnaire, there are no hard and fast rules. These guidelines have been developed to help avoid some common mistakes and pitfalls of both novice and experienced survey researchers.

- Avoid complexity: Use conventional language that is appropriate for the target audience. To get accurate information, survey questions rely on standard grammar, punctuation, and spelling conventions. Write with a sixth-grade reading level in mind, and limit the length of each question. This will help ensure your questions are easy to comprehend and will maximize respondent understanding. This is not always easy to do, nor is it intuitive. It is suggested that the survey be reviewed and tested by individuals who are proficient in both reading and speaking the language in which the survey is written. You should also consult with content experts and potential respondents before administering the survey. See Exhibit 4.7.

- Avoid leading and loaded questions: Asking leading and loaded questions is a major source of bias in questionnaire wording. Leading questions suggest or imply certain answers or responses over others. Such questions may introduce systematic bias into your data because the wording of the question causes participants to believe there is a “better/best” answer, invalidating their responses. A question may be leading because it is phrased to reflect either the negative or positive aspects of an issue. To control this bias, a split-ballot technique may be used. This technique reverses the wording of attitudinal questions for 50 percent of the sample to help reduce the positive or negative influence of a particular topic.

Loaded questions influence respondents to respond in a socially desirable way, or are worded in an emotionally charged way. For example, some questions invite only positive answers. Other questions might be worded to make respondents feel they should answer in a socially acceptable or desirable way. Thus, the respondent’s answers may not portray their true attitudes or feelings. One method for mitigating the respondent’s urge to respond in a socially desirable manner is to offer a counter-biasing statement. A counter-biasing statement is an introduction to the question which encourages respondents to answer truthfully. The statement may, for example, reassure respondents that behavior they may consider “embarrassing” is ok and normal. This slight nudge for respondent honesty can help yield more truthful responses. Additionally, assuring respondent anonymity can help elicit their honest responses. Remember, there may be some limitation in providing complete anonymity to your respondents. Be sure you have made all ethical considerations prior to promising their anonymity.

- Avoid ambiguity: Items can be ambiguous if they are too general. Your survey questions should be as specific as possible. Indefinite words such as “frequently” or “often” have different meanings to different people and should be avoided. Exhibit 4.8 illustrates good examples of unambiguous survey questions.

- Avoid double-barreled items: A question covering several items at once is referred to as a double-barreled question and should always be avoided. There is no need for the confusion that results in double-barreled questions. Exhibit 4.9 illustrates poorly designed double-barreled survey questions.

- Avoid making assumptions: The researcher should not place the respondent in a bind by including an implicit assumption in the question. Another mistake that question writers sometimes make is assuming that the respondent has previously thought about an issue; research that induces people to express attitudes on subjects that they do not ordinarily think about is meaningless.

Exhibit 4.7

Avoid Lengthy Items

Recently, there has been a lot of discussion about the potential threat to nonsmokers from tobacco smoke in public buildings, restaurants, and business offices. How serious a health threat to you personally is the inhaling of this secondhand smoke, often called “passive smoking”: Is it a very serious health threat, somewhat serious, not too serious, or not serious at all?

_____ Very Serious

_____ Somewhat Serious

_____ Not Too Serious

_____ Not Serious At All

_____ (Don’t Know)

Exhibit 4.8

Avoid Ambiguous Items

How often do you feel that you can consider the alternatives before making a decision to follow a specific course of action?

_____ Always _____ Fairly Often _____ Occasionally

_____ Seldom _____ Never

Which of the following best describes your working behavior?

_____ I never work alone.

_____ I work alone less than half the time.

_____ I work alone most of the time.

Exhibit 4.9

Avoid Double-Barreled Items

- Please indicate your degree of agreement with the following statement: “Wholesalers and retailers are responsible for the high cost of meat.”

____ Strongly Agree ____Agree ____Uncertain ____Disagree

____Strongly Disagree

- Between you and your husband, who does the housework (cleaning, cooking, dishwashing, laundry) over and above that done by any hired help?

_____ I do all of it.

_____ I do almost all of it.

_____ I do over half of it.

_____ We split the work fifty-fifty.

_____ My husband does over half of it.

Specific Guidelines for Asking Survey Questions

The following guidelines are useful to consider when asking survey questions. You may find that in your survey, some of these guidelines are more relevant or important than others.

- Use Time Periods That Are Related to the Importance of the Question:

Asking respondents “how often” leads them to generalize about their behavior, and they are more likely to portray their ideal behavior than their average behavior in reality. Periods of a year or more can be used for major life events such as the purchase of a house, occurrence of serious illness, birth of child, or death of a parent, since these events happen very infrequently. Periods of a month or less should be used for questions that involve regular/daily events, because this provides a frame of reference that makes it easier to recall. Asking people to remember relatively unimportant events over long periods of time leads to too much guessing; however, you do not want the period to be too short because the event in question may not have occurred during that timeframe. Exhibit 4.10 illustrates good and poor use of time periods in survey questions.

Exhibit 4.10

Poor: How long has it typically taken you to fall asleep during the past six months?

Comment: Too much time has probably elapsed for the respondent to recall this information accurately. Furthermore, the amount of time to fall asleep has probably varied considerably over the course of six months, making general estimation a truly difficult task.

Better: How long has it typically taken you to fall asleep during the past two weeks?

Poor: In reference to your car accident a year ago, how many visits have you made to a physician in the past six weeks?

Comment: The number of visits made to the physician in the past six weeks is probably different from the number made in the first weeks after the accident.

Better: In reference to your car accident a year ago, how many visits have you made to a physician?

- Use Complete Sentences:

Complete sentences, whether as statements or questions, express a clear and complete thought, as illustrated in Exhibit 4.11.

Exhibit 4.11

Using Complete Sentences and Questions

Poor: Place of residence?

Comment: Place of residence means different things to different people. For example, some participants might answer Los Angeles, but another respondent might say California, the United States, or 15 Pine Road.

Better: What is the name of the city where you currently live?

Poor: Accidents among children are . . .

Comment: The statement is unclear. A respondent might say “terrible,” “the leading cause of death among children under the age of 12 years,” “underreported,” “a public health problem,” and so on.

Better: Indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statement: “Accidents among children are a public health problem in the United States.”

Exhibit 4.12

Avoiding Abbreviations

Poor: In your view, does USC provide an education in liberal arts that is worth its yearly tuition?

Comment: If this question is being asked of many Californians, USC will stand for the University of Southern California. But for others, USC can mean University of South Carolina or University of Southern Connecticut.

Better: In your view, does the University of Southern California provide an education in liberal arts that is worth its yearly tuition?

- Avoid Abbreviations:

Abbreviations should be avoided unless they have been previously defined, or are commonly understood. For example, most people are probably familiar with the abbreviations USA and FBI. Conversely, abbreviations specific to state or industry may be confusing for individuals outside of that community. If in doubt, spell it out, as shown in Exhibit 4.12.

- Avoid Slang, Colloquial Expressions, and Offensive Terms:

Slang and colloquialisms should be avoided because their meanings change frequently and people can disagree about their meaning. The problem in using slang and colloquialisms is that if you plan to report the results of the survey to a general audience, you need to translate the slang accurately. Anything less than an expert translation may result in loss of meaning.

- Be Careful of Jargon and Technical Expressions:

Survey questions should avoid jargon and technical terms (see Exhibit 4.13). If you have reason to believe that your group is homogeneous and familiar with the terms, it may be acceptable to use them; however, you must then be concerned with how understandable a broader audience will find the results.

Exhibit 4.13

Avoiding Jargon and Technical Terms

Poor: Should a summative evaluation of “Head Start” be commissioned by the U.S. government?

Comment: The term “summative evaluation” is used among some specialists in program evaluation. It means a review of the activities and accomplishments of a completed program or of one that has been in existence for a long time.

Better: Should the U.S. government commission a history of “Head Start” to review its activities and accomplishments?

- Have the Questions Reviewed by Experts:

Experts are individuals who are knowledgeable about either survey question writing or the subject matter of the survey. Experts can tell you which survey questions appear too complex, or too long or difficult to be answered accurately.

- Have the Questions Reviewed by Potential Respondents:

A review by potential respondents helps guarantee that the survey’s questions are understandable, clearly communicated, and if relevant, use appropriate jargon. For example, if you plan to survey teens in high school to find out about their eating habits, then the reviewers should be high school teenagers.

- Adopt or Adapt Questions That Have Been Used Successfully in Other Surveys:

There are several databases that provide survey questions to the public. Among these are questions asked by the U.S. Census Bureau. These sample questions have already been reviewed and have been shown to collect accurate information. Use them for your survey when appropriate.

Guidelines for Asking Questions on Vital Statistics and Demographics

- Learn the Characteristics of The Survey’s Targeted Respondents:

To ensure the response categories you’re using make sense, it’s important to research and know the characteristics of your target audience. You can find out about characteristics of respondents by checking census data, interviewing the respondents, asking others who know about the respondents, and reviewing recent literature.

- Decide on The Appropriate Level of Specificity:

An appropriate level of specificity is one that meets the needs of the survey, but is not too cumbersome for the respondent. Remember, a self-administered survey and telephone interview should have no more than four or five response categories.

- Ask for Exact Information in an Open-Ended Format:

One way to avoid having many response categories is to ask respondents to tell you in their own words the answers to demographic questions. Respondents can give their date of birth, age as of a specified date, income, zip code, area code, and so on; however, it is important to prompt respondents with a desired response format to make cleaning and interpreting this information easier for the researcher. For example, if you are asking respondents their date of birth, use the response prompt “DD/MM/YY” or “DD/MM/YYYY.” This decreases the frequency with which respondents will provide incomplete answers such as “June 30th,” omitting critical information and requiring the researcher to rewrite their response into a desired and consistent format.

- Use Current Words and Terms:

The words used to describe people’s backgrounds change over time. Outmoded words are sometimes offensive. For example, individuals who participated in research studies were previously referred to as “subjects”; however, contemporary scholars now refer to these individuals as “participants.” If you borrow questions from other sources, check to see if they use words in a contemporary way. Terms such as “household” and definitions of concepts such as wealth and poverty also change over time.

- Decide If You Want Comparability:

If you want to compare one group of respondents with another, consider borrowing questions and response choices from other surveys. For example, if you want to compare the education of people in your survey with the typical Americans in 1990, then use the questions that were asked in the 1990 Census. If you borrow questions, check to see that the word terms are still relevant and that the response choices are meaningful.

What Is the Best Question Sequence?

The order of questions may serve several functions for the researcher. For example, if the respondent’s curiosity is not aroused at the outset, they can become disinterested and terminate the interview or provide quick responses to questions to which they haven’t given proper thought or attention. Order bias can result from the order in which answer choices are presented, or from the sequencing of questions. Randomization of questionnaire items helps to minimize order bias. When using attitude scales, the first concept measured tends to become a comparison point from which subsequent evaluations are made (i.e., anchoring effect). Randomization can also help minimize the effects of this.

More specific questions tend to influence more general ones; thus, it is advisable to ask the more general questions before specific ones. This technique is known as the funnel technique, and it allows researchers to understand the respondent’s frame of reference before asking more specific questions about the respondent’s intensity of opinion or amount of knowledge about the subject.

Filtered questions minimize the likelihood of asking questions that are inapplicable. These questions may be used to obtain information which the respondent may be reluctant to provide. For example, a respondent is asked “Is your family income over $30,000?” If the respondent answers “no” to this question, the respondent will be filtered to the question “Is your family income over or under $10,000?” If they responded “yes” to the previous question, the respondent will be filtered to the question “Is your family income over or under $50,000?”

What Is the Best Layout?

The layout and attractiveness of the questionnaire can help greatly increase response rates. It is worth considering using a portion of your budget—which might have been used as an incentive—to improve the attractiveness and quality of the questionnaire. Questionnaires should be designed to appear as short as possible. Experienced researchers have also found success in carefully phrasing the title of the questionnaire, special instructions, and other tricks of the trade.

How Much Pretesting and Revising Is Necessary?

Usually, the questionnaire is tested on a group of individuals who are selected on a convenience basis or because the individuals are similar to those who will ultimately be sampled. It is not necessary to get a statistically valid sample for pretesting. Pretesting allows the researcher to determine if the respondents have any difficulty understanding the questionnaire, or if there are any ambiguous or biased questions, which can help catch any mistakes before the survey is administered to the population of interest.

Additionally, a preliminary tabulation of the pretest results often illustrates that although a question may be easily understood and answered, it may still be inappropriate if it does not address the problem or original objective of the survey.

Pretests are typically conducted to answer questions about the questionnaire, such as:

- Can the questionnaire format be followed by the interviewer?

- Does the questionnaire flow naturally and conversationally?

- Are the questions clear and easy to understand?

- Can respondents answer the questions easily?

- Which alternative forms of questions work best?

Pretests provide the means for testing the sampling procedure and may also provide estimates for the response rates for the mail surveys and completion rates for telephone surveys.

Survey Design Checklist:

____ Have the objectives of the survey been defined?

____ Does each survey item relate to an objective?

____ Is there appropriate use of rating and/or written-response questions?

____ Is each question simple, concise, and easy to understand?

____ Does each item assess only one concept?

____ Are double negatives avoided?

____ Are definitions provided, when necessary?

____ Are as few items as possible used?

____ Are the questions in a logical order (grouped together, where appropriate)?

____ Are background questions (such as pay code) used only if necessary?

____ Does the survey appear easy to complete (aesthetics, length)?

____ Is the survey pretested before administration?

____ Have plans been made for data entry and analysis?

____ For sampling, is the correct sample used? (See Chapter 5)

Part II—Infinity Case Study Possible Answers

Possible Answers:

If you were working for Infinity Insurance, how would you go about gathering a valid sample?

Use a random sampling technique by gathering a database of potential respondents from a variety of public record sources and randomly selecting individuals from this list. Given that Infinity Insurance is interested in targeting two specific market populations, one might consider a stratified random sample (subdividing a population into items into separate subpopulations, or strata), breaking down market segments by age, and randomly sampling from each strata. To ensure a representative and equivalent sample is collected from each strata, one could also use quota sampling (which requires that representative individuals are chosen out of a specific subgroup. For example, a researcher might ask for a sample of 100 females, or 100 individuals between the ages of 20 and 30).

What type of survey administration might be most beneficial?

Given that Infinity Insurance is targeting two specific market segments, one might consider a multimode approach using several techniques. By leveraging public record resources, the researcher may be able to acquire a representative database of potential respondents. The first contact with participants might be a postcard/letter communicating the intent of the study, rewards for participation, and inviting respondents to complete an online survey. After this initial contact, a follow-up phone call might be made using an address-based sampling approach and random digit dialer. This phone call would give potential respondents the option to complete the survey via the telephone or online. Thus, it gives both target populations the opportunity to complete the survey through a medium that they are most comfortable with, in the hopes of boosting response rates. Furthermore, using this multimode approach might encourage respondent’s participation by overcoming inattention to a particular survey mode. When using this multimode approach, however, it is important that the branding between various modes of administration be consistent (i.e., color, graphic design, and logos).

Should you incorporate incentives into the survey?

Research by Dillman and colleagues1 has demonstrated that incorporating cash or token rewards can help boost response rates; however, they suggest offering these incentives only after making initial contact with the respondent via another modality. For example, one might consider making initial contact with respondents via telephone or mailed postcard, inviting them to participate in the survey. After initial contact has been made, you could reach out to participants a second time, offering a cash/token incentive. It may be cost-effective to see how many responses can be garnered for free before paying participants.

Should you pilot the survey?

Generally, it is considered best practice to pilot your survey, both for pragmatic and financial reasons. Pragmatically, piloting helps the researcher ensure the questions are correctly understood by participants, allows the researcher to determine if questions are unintentionally leading participants to respond in a certain way, and helps determine an estimated average time for survey completion. Financially, this can be beneficial to help ensure a minor mistake doesn’t invalidate the accuracy of an entire data set. For these reasons, it was decided to pilot the survey.

What issues might hinder you from creating a statistically valid sample?

Nonresponse error, nonrandom sampling, coverage error, measurement error.

1D.A. Dillman, J.D. Smyth, and L.M. Christian. (2014). Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons).