4

Tailoring Your Communication to Your Goal

Though you should always consider your intent when you're crafting a communication, sometimes you can build on that exercise by using specific media, formatting, language, or information ordering to meet specific goals. The more measurable and specific your goal, the better you'll be able to customize your communication to meet the needs of your audience. Here are some of the most frequent use cases we encounter at Stanford and beyond.

Pitching

Any time we try to gain buy-in for an idea, even one as simple as where to meet a friend for lunch, we're pitching: proposing the merit of an idea for others’ support and collaboration. But in this chapter, we're going to focus on the type of pitching that challenges entrepreneurs every day: pitching your business venture or collaboration. From the thousands of pitches we have seen at the GSB and beyond, we've gathered our best tips for creating meaningful, memorable content and for tightening your message to engage your audience. We'll lead you through identifying the problem your idea is solving, the solution you're offering, the market you're targeting, and the business you're planning. Then I'll give you a step-by-step look at a pitching exercise I offer my students to refine their message for presentation.

Creating Your Pitch Content: Problem, Solution, Market, and Business

For as long as I've been teaching presentation skills—and I confess it's been quite a long time—I've encouraged entrepreneurs to start with content when creating an engaging, memorable pitch. I think one of the finest resources out there right now about creating pitch content is Chris Lipp's The Startup Pitch. Chris has taken a survey of the thousands of pitches he's seen here in Silicon Valley and beyond to analyze what exactly entrepreneurs include to ensure an effective pitch. From that analysis, he's devised a very simple four-part structure to an effective pitch (Figure 4.1).

First, we must convince the audience of the problem. Then, we have to present our solution—and its direct connection to the details of the problem we've just outlined. Next, we must demonstrate that there's a market for solving this problem. It's not simply that we have a problem parking in downtown San Francisco, for example, but that many people share this San Francisco parking problem … and that many cities share this issue and would benefit from the solution we're offering. (And not only would they benefit, but they'd pay for that solution!) Finally, we need to demonstrate that we have a viable business model: that by solving this problem for this market, your investors stand to receive revenue. Whether that model is an ad model, a subscription model, direct sales, or B2B sales, we need to demonstrate that we have a clear plan to extract value.

Figure 4.1 Chris Lipp's pitch formula

Source: From Startup Pitch by Chris Lipp. SpeakValue 2014.

Let's look individually at each of these four areas.

Problem As you begin by describing the problem, it's important to describe it clearly, making sure that your audience understands the pain of the problem. Why is this such an issue? What are the repercussions of this problem and why do they matter? If the problem is familiar and widespread, it may not take you long to establish the stakes. But if the problem is lesser known or more nuanced, you may need to share video, graphs, or testimonies about why it needs to be solved. Raise the stakes by noting any trends you see for this problem. Is it getting worse as the population ages? Do environmental, economic, or time-based factors increase its impact over time? If that's true, then you can make the point that the need for your solution will only increase over time. Be sure that your audience understands the immediacy of the problem before you move on to phase two: your solution.

Solution Chris Lipp opens his conversation of solution by addressing the importance of your USP, or unique selling proposition. Why are you able to solve this issue in a way that others haven't been able to yet? What's going to set your startup apart from anyone else who's trying to work in that space? In other words: why you, why this, why now?

If you have the opportunity to lead us through a demo of your solution, or to take us to your app or your site, the benefits of that hands-on experience with your offering can only serve your pitch.

Finally, be sure that you talk about the benefits of your solution to your stakeholders. Make sure we understand why your solution to this problem will be of use to us, your audience. Too often people are tempted to speak only about the features of their product, but they're leaving out an important pitching factor when they do so. Think of Steve Jobs introducing the iPod Nano: He didn't tell us it had 16GB of memory or that it was two inches wide by three inches deep. Instead, he said, “Imagine a thousand songs in your pocket.” He described the features of the iPod Nano by talking about the benefit to the user. Outlining the benefits of your solution is absolutely crucial to gaining investment in your product.

Market As you move your focus to market concerns, you'll want to talk about the initial target market you've identified as well as any expansions you anticipate beyond that initial market. Share an estimate of the market size. Here's where you demonstrate to us that you've done your research—not only about what the market is, but what potential it holds. As you discuss the market, you'll want to effectively capture the advantages of serving this market of consumers that you're targeting. Perhaps this is a group of high-net-worth individuals to whom other products could be introduced. Perhaps this is an underserved market for whom your offering could be a gateway to other products and services. Be certain that you establish not only that you know your market well, but that serving the market you have in mind offers explicit benefits.

Business Last, you'll want to cover the details of the business itself. What is your go-to-market strategy? Specifically, you'll want to share when and how you're planning to bring this product or service to the market. It's important to share your model for earning revenue and to offer some clarity around when you think that revenue model will begin to be profitable for you. Familiarize your investors with some milestones at which they could expect to see some return on their investment.

As I look at this model—Problem, Solution, Market, Business—I often think of it as a baseball diamond. First, I have to get to first base, where I explain the problem and convince investors that the problem needs to be solved. Second base is where I reveal my solution to this problem: my unique selling proposition. Third base: There is a market for this solution, an opportunity that needs to be captured. But the home run, where we score an investor, is demonstrating that I have a business model that will capture revenue to serve this market, offering a solution to this problem.

How much time you spend on each of these components depends on the familiarity and intricacy of the problem you're solving and the solution you're offering, and the context that your investors already possess. You'll customize the proportion of time you spend on each element, depending on the concerns of your business and the level of knowledge that your audience has. But I urge you not to skip any of these important steps. They work together to offer your audience a clear picture of why they should help you to bring your idea to life.

Building the Bridge: An Exercise to Tighten Your Pitch

Much of the pitch work I've done at Stanford has been with teams of entrepreneurs preparing to deliver a pitch together. Most of this has been through Stanford's highly successful Ignite Program, started by Garth Saloner and now led by Yossi Feinberg. This certificate program is offered on campus in the summer as a full-time four-week session and in the winter as a part-time three-month experience. Each summer, we also invite a group of military veterans to campus for a tailored version of Ignite, addressing their distinct needs as they transition from the military to civilian life as entrepreneurs.

In these team settings, one participant acts as the “idea generator”—the person who proposes the product or innovation for the entire team's work, from the creation of the business plan to the pitch. I visit the participants early in the course to provide the basics of effective pitching; then, about a week before their final pitches to an invited group of VCs, I return to provide coaching for the teams.

These coaching sessions serve as a gating function for the teams. Almost always, it's clear that few groups have actually rehearsed as a team before meeting me. They often present five or six “individual presentations” on the same topic. There may be a clear delegation of duties, but not a sense of cohesion. They've worked in silos to prepare the material. Some teams even show “frankendecks”—a slide deck stitched together with inconsistent formatting, colors, and fonts, giving a sense that the presentation is not a single entity, but rather a collection of mismatched parts. While the pitches are rocky in this state, they're certainly not without potential. Walking through my bridge exercise often helps create the alignment needed (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Building the bridge, no pillars

To begin, I approach a full whiteboard in the classroom. On the left side, I draw one bank of a river and on the right, the opposite bank. I start on the left side, explaining, “This is Point A, where your investors begin: disengaged, uninformed, potentially even resistant.”

Then I move to the far right side: “And here is Point B, where you want them to arrive: engaged, enrolled, committed, maybe even ‘invested’ in the idea so much that they open their address books or checkbooks to help you succeed. To get from Point A to Point B, you need to construct a bridge through your team presentation to get them across the river.”

Next I draw the arch supports stretching from Point A to Point B. The arch represents the “big idea” for the innovation. I ask the students, “If you had to synthesize the pitch into seven to eleven words, few enough to fit on a billboard, what would you say?” We wordsmith for a while on this and ultimately settle on a working theme for the pitch that encompasses problem, solution, and opportunity. That idea becomes the bridge connecting Point A to Point B (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Building the bridge, with pillars

Still, even with a bridge scaffold from A to B, we need a platform on which to walk from one side to the other. Each speaker provides a “little idea,” which edges us from the first words of the pitch (capturing attention) to the final words of the pitch (inviting participation). In this portion of the activity, students begin to see how their pieces connect to the others. Team members will begin to trade content elements with one another. This more holistic view of the presentation starts to take on value.

Figure 4.4 shows one example of a bridge completed by 2019 Veterans Ignite Program team. They generously allowed me to use this to illustrate the concept. A team of six came together around one member's startup idea, Amissa, an innovative wearable device to help track Alzheimer patients who've wandered away. Jon Corkey, a 25-year Navy veteran, founded the firm based in Charlotte, North Carolina. After beginning the startup process on his own, he came to Stanford to flesh it out more fully and build his skills as an entrepreneur. Once I had sketched out the bridge exercise on the whiteboard, Jon's team struggled to define the big idea or overarching theme for the presentation. Usually, I try to encourage a team to capture the essence of this theme in seven to eleven words (like a billboard or bumper sticker). We settled on “Alzheimer's sucks! We support patients, families, caregivers, and researchers with a tracking companion.”

Figure 4.4 Building the bridge, totally filled out but no CTA

Next I went to each member of the team and asked them to similarly articulate the “little idea” that they were contributing to the larger presentation. Each little idea would fit into the big idea with the same constraints (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.5 Building the bridge, totally filled out with CTA

But the real magic came when Jon synthesized his closing call to action, which connects the bridge back to the other shore (Figure 4.5): “We have traction. We need contacts and capital to succeed.”

A few days after our work together, the Amissa team delivered their final pitch to a group of VCs who found the team's work and Jon's innovation impressive. The team shared with me that the bridge helped them to be more compelling and more cohesive. Jon's now back in North Carolina pursuing the venture even further. You can follow his progress at Amissa.com.

Pitching on CUE: Curiosity, Understanding, and Evangelism

Before we end this section on pitching, there's one final framework you may find helpful. Our colleague Burt Alper, who teaches pitching in several settings, reminds his entrepreneurs to remember the acronym CUE. He suggests that all pitches have three primary segments: curiosity, understanding, and evangelism.

During the curiosity phase, an entrepreneur should capture the audience's attention. Make the potential investors or partners curious, ideally dying to know more. You can achieve this curiosity by presenting compelling research, asking insightful questions, or sharing vivid stories. However you decide to do so, draw your audience in and inspire them to want to know more.

The next stage, Burt explains, is where you must create understanding. You might create understanding by providing technical details, sharing sketches, or conducting a demo of your product. Standing on the platform you've built in the first phase, you must explain the innovation in a clear and simple fashion so that your audience truly understands it.

But creating curiosity and providing understanding is not enough. The third phase is to inspire the audience to become evangelists. He advises entrepreneurs to talk about future potential, massive scale, or significant value the product or service will provide. You want to create a reaction like “I can't wait to tell my partners about this” in the minds of those you pitch. As we have shared elsewhere in this book, you'll be most effective if you can “sell” in a way that feels authentic to you, yet still effective for the situation. Don't hesitate to “ask for the order.” Invite the listeners to take an action that moves them closer to being engaged and enrolled.

If you have made your audience curious, allowed them to understand your proposition, and evangelized through a clear ask, you will have met the main criteria of a successful pitch. If this pared-down model appeals, consider the CUE model another tool in your pitching toolbox.

Storytelling

At bedtime, I tell my children Roma and Joshua stories. No matter how many stories I tell them, they always ask for “just one more.” Even from a young age, it seems we're hard-wired to enjoy a well-told story—and for good reason. As adults, we know that stories can do the work that other types of language can't. Sometimes stories are the best way to persuade, to activate emotions, or to illustrate an important point. And they're also a way to connect with audiences through the personal, the visual, the surprising, and the memorable details we share.

Whether you're telling a story in a presentation, a business meeting, or at a networking event, the principles of good storytelling remain the same. Over our years teaching future leaders how to connect through story, we've identified some best practices that will help you make sure that your story moves people, holds their interest, and makes your message stick.

Crafting Your Story

Remember that every good story charts a change—even a subtle one—in the conditions, attitude, actions, or feelings of the characters. What is the change your story charts? “We changed our environmental practices” is not yet a story, because it doesn't reveal any change. But “We were using three hundred plastic straws a day. One day, we saw a presentation on the effect of our waste. Then we changed our practice and eliminated plastic straws completely” is indeed a story (if a bare-bones one!). It shows a change over time. Once you're clear on the change your story reveals, experiment with how the techniques below can bring your story to life.

Parachute in The best storytellers drop us right into the action without preamble. Rather than starting with, “I'd like to tell you a story about a time when I …,” place us directly in the scene of action to set the tone for the story. You can include your takeaways and learned lessons later in the narrative.

Choose your first and final words carefully Just as you'll parachute in with a hook that grabs the audience's attention, you'll want to conclude your story with an image, reflection, or call to action that leaves them thinking about your story after it's done. Be intentional when choosing your opening and your closing.

Follow the “Goldilocks Theory” of details Not too many, not too few. If you offer us too many details, we may get lost, or worse, bored. If you don't offer enough details, we may lack the context to grasp the story fully or to see ourselves inside your tale. Here are some of the tips Kara and I often share for how to get just the right amount of detail.

To offer less detail: Look for descriptors that are doing the same work and see whether you can eliminate doubles. Is the room both “crowded” and “claustrophobic”? These words are telling you the same information about how the room feels. Doubles can describe how something looks, feels, tastes, sounds, or smells—keep an eye out for them, and limit yourself to just one of each category for every item you're describing.

To offer more detail: Use the five senses. Is there a spot in your story where you see a lack of detail? Ask yourself, “How did this look, sound, smell, taste, feel?” You can also ask yourself, “What was the main character thinking at this moment?” These questions are prompts that may help you to populate your story with details that will help your reader connect.

Know your why A good story has a job to do: it illustrates a point, convinces someone of an idea, or reveals something true. Why are you telling the story you're telling? What do you hope your audience will know or feel as a result? Think of this part of your brainstorming process as the “I tell you this because …” section. Often, in a business context, it's valuable to articulate to the audience what you want their takeaway to be. But whether you choose to share the takeaway verbally or not, it's essential to know the takeaway yourself. If you need a place to start, you can return, as always, to the AIM framework.

Delivering Your Story

From our conversation about verbal, vocal, and visual communication, you know that crafting your story's narrative is only part of the storytelling opportunity. A great storyteller also considers how to deliver the story to best effect, capturing and holding the audience's attention throughout.

Focus your delivery on “one person with one thought” When speaking to a group, focus on one person at a time, for four to seven seconds. As you tell your story, try to connect with each individual if possible. Don't wash your eye contact over the crowd like a lighthouse, but actually connect with individuals. Consider even “casting” a member of the audience as a character in your story as you tell it.

Consider the power of poetry Use fewer words to carry more meaning. My high school English teacher, Mr. Wessling, used the analogy of the “magic grain truck” to educate us about poetry. He invited us to imagine: What if a magic truck allowed a farmer to haul seven times the amount of grain that a normal truck usually holds? (Can you tell I grew up in Kansas?) We developed a long list of benefits such a truck would provide: fewer trips, less fuel, more free time. Then he concluded: “Well, that's what poetry is. Using just a few carefully chosen and arranged words to carry much more meaning than their usual weight.” That imagery from over three decades ago reminds me of the power of poetry.

Use silence for impact and emphasis When a composer writes the score for a symphony, she places a rest in the music when silence is called for. That rest is as much a part of the music as the notes. Silence is a powerful and underutilized storytelling tool. Intentional silence draws emphasis to what was just said or what is about to come—and allows others to contribute their own interpretations.

Delivering Your Story with Data

Have you ever had the experience of seeing data that you knew you'd never be able to unsee? When that story was told so well, and the data was so rich, that you knew you'd never forget what that data meant to you? For me, that moment was in August of 1999, when my best friend, Javier, twisted my arm to get me to sign up for the Alaska AIDS Vaccine Ride. For six days, 2,500 of us rode our bikes from Fairbanks to Anchorage, Alaska, raising money for the AIDS vaccine.

The morning that we set out on our first ride, the organizers gathered us all together for an event meant to inspire us—not just to keep riding, but also to keep fundraising and collecting pledges on behalf of the vaccine long after our ride was over. As we sat there in our bike gear ready to take off, the organizers brought 34 people up onto the stage, all in jerseys bearing the logo of the ride. Twenty-eight of them were wearing black jerseys, and six of them were wearing yellow jerseys. Those 34 people represented the 34 million people affected by AIDS and HIV throughout the world at that time. The people in black jerseys represented the 28 million people in that group without access to the anti-retroviral drugs that we have access to here in the west. The six people in yellow jerseys represented the six million affected people—mostly living in the developed world—who had access to the drugs. Then 12 children stepped up onto the stage, all wearing red jerseys. These kids represented the 12 million children—mostly orphans living in Sub-Saharan Africa—who had lost both mother and father to the disease.

That example of storytelling with data still chokes me up 20 years later. And I can remember the numbers because someone was thoughtful about designing that story in a way where the numbers made a difference to me. This type of visual storytelling with data may not be available for most of the communication you do day to day, but I want to offer it as an aspirational touchpoint for thinking about what data can do for your audience when you position into an effective, compelling story.

Albert Einstein famously said, “Make everything as simple as possible, but no simpler.” That's precisely what we're aiming for with the following tools for crafting data into story.

Develop the story before you develop the graphics If you've ever seen an unintelligible slide, squinted at meaningless curves across confusing axes, or tried to make sense of what a scattergraph was trying to tell you—and we are sure you have!—you've witnessed the phenomenon of graphics preceding story. Not only is this approach hard to understand, but it fails to tell a story that will drive outcome for your audience. Thus the critical importance of developing your story before you develop your graphics. Think of your graphics as the tip of your communication iceberg: a tip of an iceberg represents only 10 percent of the total mass; fully 90 percent lies beneath the surface. Your graphic isn't your whole story—it's a representation of a small part of it.

So rather than starting by looking at your chart to find a story, start by looking at the data. Do some analysis within your idea to identify the themes, takeaways, and trends that are worth highlighting. Once I'm clear on the story I want to tell, sometimes I find it's helpful to test several different charts, graphs, or ways of visualizing the story to see which one works best.

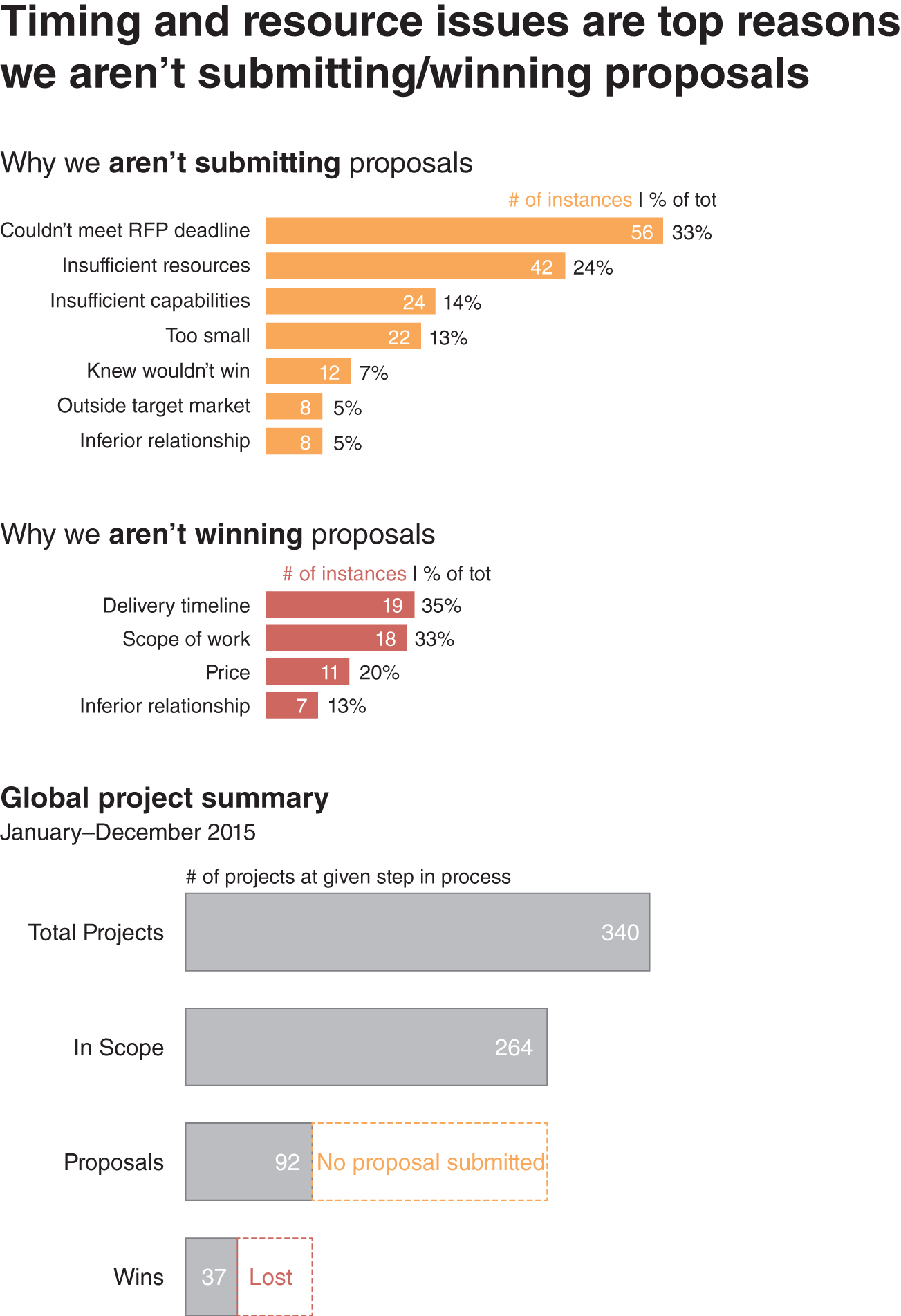

Anytime we sit down to craft a narrative, it's valuable to consider the structure of a well-told story. In her 2011 TEDx East talk, Nancy Duarte references Freytag's pyramid to illustrate a structure I find particularly useful (Figure 4.6).

This model is over 100 years old, but we still refer to it today for good reason. It contains the most important elements of a story well told. Take a look at the beginning of the story path—notice how short the section devoted to opening and exposition is. Nine out of ten times, we don't need nearly as much windup as we think we do. Rather, we can keep the momentum of the story moving forward by moving to the central conflict as soon as possible. That conflict or inciting moment will create the action of our story, lead to its climax, and depending on what kind of story you're telling, to the falling action and the resolution.

Figure 4.6 Freytag's pyramid as referenced by Nancy Duarte

Think of any great film you've seen in the past few decades. As a parent of a toddler, I'll admit the first movie that comes to mind is Moana. (Hey, it's good!) The setup of the movie is concise and the conflict arrives almost immediately: Moana's island lacks vegetation and the community doesn't have enough food. Most of the movie is devoted to the action as Moana sets out to find the all-powerful Heart of Te Fiti, finally finds it, and brings it back to her island. The quick resolution that follows shows vitality returning to the island.

This is the same kind of arc you can find in your data. What's the conflict? What's the action being taken to resolve or change the conflict? Your story may end at the climax if you're trying to get people to take action. Either way, be thoughtful about your story's arc.

Know and honor your audience Well, here we are, back at AIM again. That's because to tell your best story, you'll need to be thoughtful about who your audience is. What's the appropriate level of data and type of illustration that will make sense to them? How sophisticated is your audience? Will they understand regression analysis? Will they be served by synthesized information, or will they appreciate having data broken down for them in a more step-by-step fashion? Think about the level of detail and sophistication you want to apply to the data you share.

Avoid the food charts (pies, donuts, and spaghetti) The classic pie, donut, and spaghetti charts are rarely your best choice for telling a story with data, not only because, if you're like me, they're likely to make you hungry. These charts rarely format data in a way that is accessible to your audience—they make your data very difficult to interpret. Take a look at what I mean in Figures 4.7, 4.8, and 4.9.

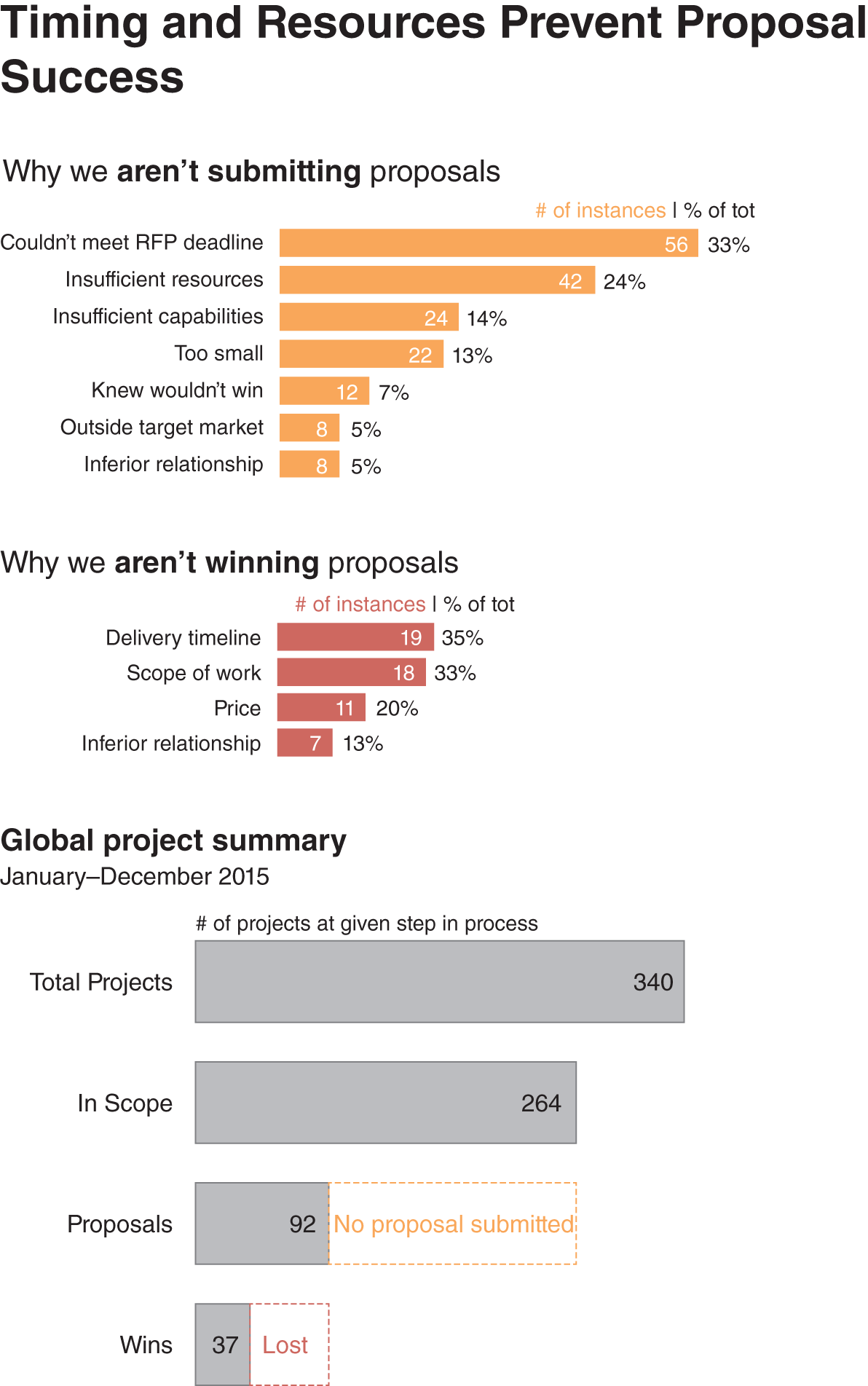

Anyone trying to interpret the pie chart in Figure 4.7 would be hard-pressed to come up with a story. Is the bottom half of the pie chart meant to indicate some cautionary content? What should it mean? It's a lot of work to try to figure out what the presenter is telling us.

Now take the bar graph in Figure 4.8. This first bar graph shows exactly the same data, visualized differently. Can you interpret the data more easily now? You should be able to have a better sense of the takeaway your presenter has in mind when looking at the data in this different format. Especially when your data has many components or slices, you don't want to represent it in a pie, as the small visuals that result will be confusing.

Figure 4.7 Original pie chart

Source: Storytellingwithdata.com

Figure 4.8 Revision showing bar chart instead

Source: Storytellingwithdata.com

Figure 4.9 Further revision with stronger, tighter title

Source: Storytellingwithdata.com

Break a complex story into multiple slides or reveals But you can simplify your slides even further. That leads us to another solution to the problem of a complicated slide: consider breaking it into multiple slides or reveals. You don't have to fit your whole story in a single chunk. Notice how in Figure 4.8, she broke the data into three separate pieces: “Global Project Summary,” “Why we aren't submitting proposals,” and “Why we aren't winning proposals,” making it even easier to understand.

I've noticed that using some simple animation to dole out information piece by piece can also make it easier for your audience to follow your story. Even if your whole team has the deck in front of them, if you animate the slide that's up on the screen, they'll follow the movement and be more likely to match the pace of your story. Slowing it down can make it easier for others to follow.

Create strong headings with power verbs As my students well know—and by this point in our book, you do too—I have a strong bias against weak verbs like is, are, was, were, has, have, had. During our discussion of strong writing, we covered the reasons that stronger words can be more specific, foster concision, and inspire action. But they're just as important when you're applying data to story, or story to data. In Appendix A, you'll find a list of 156 power verbs that you can use instead of these frequent offenders. Those words will inform and compel your audience in a way that the “basic seven” can't. Most importantly, your headings for every slide or every section of your data should tell the story for that slide or section. Don't make your audience do the hard work of deciphering the story from among a cluster of unclear words—they may not be motivated or able to do so. Be a generous presenter by offering your story in your heading using clear language.

Simplify graphics for greater impact When we offer the audience a complex image, we have less control over where they focus and what they take away. Keeping an image simple allows the audience to focus on the message we want them to remember. If you have backgrounds and borders, removing those is a good place to start. Eliminate legends and axis labels if possible; any time we include those, we're forcing our audience to look down or to the side, away from our central focus.

Then, go on to highlight the data point that matters. If your data story is about how bacon has the most calories of other foods in its category, consider adding a color to your bacon column, but leaving the comparison columns in gray.

Of course, the process of simplification can go too far. As we mentioned before, you do want to make things as simple as possible—but no simpler! But making a few small tweaks to the way you visually present your data can make it easier for your audience to identify the story you want it to tell.

Drill with real data The best way for you to become proficient at storytelling with data is to practice these skills using real data. Take some data you or your company are working with right now. What stories can you uncover from the data you have? What conclusion is it leading you to draw? How could you use the techniques above to reveal those conclusions to your audience?

This is the exact assignment I offer to my students at Stanford. I break up the group into cross-functional teams and give each group an identical data set. I then provide them with an intended audience and instruct them to craft a compelling story from the data. They should illustrate that story in no more than three slides (keeping it simple!). Finally, I provide a “campfire setting” where each group shares the stories they crafted.

As with every other theme in this book, practice is what will get you closer to mastery. But practicing with real data will make your practice relevant, interesting, and unique.

Disclosing Personally

From time to time a leader may choose to share something with an audience that crosses over the line from business to personal. Steve Jobs did this when he disclosed his terminal illness. His successor, Tim Cook, did this when he chose to come out of the closet as gay. Sometimes a leader is proactive and chooses what and when to share something of a personal nature, while at other times, particularly with a scandal or misdeed, leaders don't control the narrative. There are countless examples of this in business, politics, and entertainment: Anthony Weiner, Harvey Weinstein, and Al Franken to name but a few. In fact Wikipedia has a list that runs several pages of such names.

In the LOWKeynotes program, students have chosen to share a wide range of personal facts from their own lives, ranging from struggles with depression, to sharing less visible disabilities, to being fired from their own startups, to learning of a parent's addiction to crack cocaine. I'm not sure there's a right way to do this, but I'm pretty sure many “wrong ways” exist to do this. In this section, let me provide some best practices to consider for such vulnerable self-disclosure.

No conversation about vulnerability today can begin without a reference to Brené Brown and her remarkable work on shame and vulnerability. Perhaps no individual has done more to untangle the stigma of shame from the power of vulnerability. Her initial TEDx Houston talk in 2010 has amassed over 42 million views, leading to a subsequent TED talk and a New York Times best-selling book, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. If you've not read her book or seen her TED and TEDx talks, do so. They may change your life, as they have for so many others. Vulnerability is not a means to an end, but rather a choice in and of itself. If it's a choice you've made (or are weighing), consider these suggestions.

Know Your Intent and Check Your Motives

At its heart, Brown believes that vulnerability is the best treatment for shame. In Daring Greatly she writes: “Shame derives its power from being unspeakable.” As leaders we can expand our influence if we can effectively harness the distinct power of vulnerability. Yet, proceed with caution. A leader who is trying to manipulate a team or client through “the act of vulnerability” will likely not succeed in the long run. That level of inauthenticity will, sooner or later, rise up and trip that leader. Recall the AIM model from Chapter One: “As a result of this communication what do I want the audience to think, feel, say, or do?”

If your motives for self-disclosure are self-serving, reconsider your choice to share. If, on some level, you are trying to meet a personal need by sharing, this may not be the time, place, or setting. Brown goes on to say, “I only share when I have no unmet needs I'm trying to fill. I firmly believe that being vulnerable with a larger audience is only a good idea if the healing is tied to the sharing, not to the expectations I might have for the response I get.”

Share with Your Confidants First, and Take Their Counsel

It's crucial that your significant other, business partner, direct supervisor, or other key confidants know your news before you make it public. In fact, a careful conversation with such a trusted partner may be the best way to assess your intent and motivation. If people you trust and who know you well do not think it's wise to divulge the information you're considering, it may at least be worth disclosing with caution. At the extreme, you don't want these trusted people to “learn the news when everybody else finds out.”

Those who've seen Hamilton know well the scene where Eliza learns of her husband's infidelity when he self-publishes a manuscript (the blogs of the late 1700s!) offering a political defense for the affair. While torching each love letter Hamilton ever wrote to her, Eliza sings, “In clearing your name you've ruined our lives.” While dramatized for the stage, the point is well made: First, tell those you care for most. Then decide (if you have a choice), in concert with them, whether it still makes sense to share the information more widely.

Consider the Setting and the Medium

Just as you want to try to control the narrative, you likewise want to consider where and how to disclose this information. While it can be very powerful to deliver personal news in person, that may be more challenging for you and your recipients. It can be harder to process news while facing the person who is delivering it. Consider all the avenues at your disposal: handwritten note, typed email, phone call, individual meeting over a meal, small group meeting, large audience—yes, even the TED stage. If you are clear in your intent and clean with your motives, the choice of setting and medium may be fairly straightforward.

At Stanford I teach a case (written by Reynoldo Roche while an MBA student at UVA) profiling Mark Stumpp, a chief investment officer for QMA, a division of Prudential. Mark chose to undergo surgery to transition from male to female, becoming Maggie Stumpp. In 2002, when this took place, there was very little guidance for firms on how to communicate news of this kind, but Prudential did a remarkably solid job. When it was time for Maggie to return to work, her supervisor first called colleagues with close proximity to tell them the news. The supervisor called them on their home phones over the weekend before Maggie returned. Then, for other employees in the firm, a memo was sent.

Plan in Advance How to Field Questions

If you opt to deliver your information orally, you should also choose whether you will take questions about this announcement or not. If you choose to merely share in one direction, without taking questions, you should provide a resource or avenue people can use to find out more.

I vividly recall when, in January 2009, the GSB was forced to lay off over 60 people in one day due to the financial crisis. Dean Bob Joss and Senior Associate Dean Dan Rudolph were clear on this point. All of the laid-off employees were notified on a Tuesday morning before noon. At 2:00 p.m. that day, Joss and Rudolph held a town hall to share the news with everybody at the school. They provided the evidence of the loss of endowment revenue, the rationale for the cuts they made, and the process moving forward without these staff members. Yet, knowing how emotional this might be for many people, they chose to not take any questions at this time. Rather, smaller team and department meetings were set up in the coming weeks to field questions. The clarity of this choice struck me as clear and completely appropriate. You must have some way for people to pursue answers if they have questions following your disclosure.

Prepare for the Consequences

It's best to have a “best/average/worst case” plan in place before the disclosure. It's entirely possible the news may have little to no impact; it may be more valuable for you to share than for the audience to hear. Yet, it's equally possible that it will have a greater impact than you would ever have imagined. The news could go viral (literally or figuratively) and you may have many more eyes and ears in the conversation than you ever dreamed. Quite often I find that having “planned for the worst,” the worst doesn't come to pass, but your confidence is heightened just knowing you have a plan.

Here, again, rely on the counsel of others. Find somebody you trust who has made a similar disclosure and see whether they can help you map out the potential ramifications. I don't know Chip Conley very well, but he took time to counsel me over the phone as I was considering doing my TED talk. He had similarly shared some of his own struggles in a TED talk and was generous, and candid, with his advice to me.

A Personal Story: My Own Journey of Self-Disclosure with My 2011 TED Talk

Many of you may have seen my TED talk, “Break the Silence for Suicide Attempt Survivors.” If not, please take four minutes now and watch the talk before you read the back story of this pivotal moment in my life. While the talk went live in 2011, a few months after I delivered it, the story begins at TED 2010. There, I heard a short three-minute talk by fellow participant Glenna Fraumeni that changed my life. She shared her struggles with a malignant brain tumor and her determination to persevere despite the diagnosis. She began the talk by saying the doctors had only given her three years to live; she ended by saying, “By Christmas 2011, I will probably be gone. Where will you be?”

Her probing question haunted me. I wrote in my journal, “When will I tell my story? Maybe next year?” When it came time to register for TED 2011, I saw a separate registration for TEDYou, where leaders get a chance to deliver a talk on stage. I discussed the idea with my husband, Ken, and a trusted advisor, Roger, and decided to register to speak. As a survivor of a fairly dramatic suicide attempt in 2003 (and several smaller attempts going back as far as the seventh grade), I believed strongly that we need to be more supportive of those who've survived such an attempt on their own lives.

I worked on my talk for several weeks and, again relying on trusted advisers, hit upon the structure of telling my own story in the third person. I spoke about myself as though I were someone else, a man named John. I did not know whether I would want to reveal who John truly was. So I composed a paragraph about two and a half minutes into the four-minute talk that began, “I know John's story well because I'm John.” I crafted this piece of the talk in such a way that if I chose not to, I could decide not to deliver that paragraph and the talk would still make sense. The impact would be less, but the paragraph was not necessary structurally. I had designed an “exit ramp” that I could choose to take or not take in the moment.

I prayed before walking out on stage, and knew that I would know whether to disclose when I got to that point in the talk. Today, I'm so glad that I did disclose, because I know the talk has made a much larger impact on the world with my own vulnerability visible and shame diminished. The reaction from the audience in Palm Springs was encouraging. I received a standing ovation and throughout the week people kept grabbing me for a coffee or a meal or just a hug. I was glad I disclosed.

But then TED wanted to put the talk up online. I was not sure I was ready for that much exposure. I was up for faculty reappointment at Stanford, and I didn't know how my tenured peers would feel about me admitting my struggles with depression and suicide. More urgently, I was not sure how I could face my class if the talk was seen and shared among the student body. I asked for time to decide. Even Chris Anderson himself reached out to me by email. He thoughtfully emphasized the choice was mine, saying:

In my opinion this talk would have a big impact if we release it on ted.com. With your permission, we'd very much like to. I think you will connect with a large number of people feeling the way you once did. And with people who know people in that situation. I also understand it's hard letting yourself be vulnerable in this way. I think that anyone with an ounce of humanity who sees this will find their respect for you rising. But even knowing that, it doesn't make it an easy decision. I do hope, though, that you'll be willing to do this. I think it will be a real gift to all of us.

As I considered, I reached out to my friend and faculty colleague, Jennifer Aaker, for advice. She's a well-regarded expert on meaning, purpose, and the power of story, and the author of The Dragonfly Effect: Quick, Effective, and Powerful Ways to Use Social Media to Drive Change. She not only knew the power of story and its ripple effects in social media, but also understood how such a step might impact my role in the institution and reappointment in particular. She said, “JD, you don't need to worry about the impact of a TED talk within the school. But are you sure you are ready for the attention you might face going so public with this? It could become quite intense.”

I took about another month to decide. During that time I lost another friend to suicide—someone with whom I'd attended school from childhood and graduated high school. If the intent of my talk was to “break the silence,” then it felt like posting a talk on TED was a pretty powerful way to do that. Together with the team at TED we chose June 11, 2011, as the date to launch. This marked the eighth anniversary of my suicide attempt and brought light to a day that had previously held shame and darkness. TED's support in this effort was incredible; they had extra staff online that weekend and went to great lengths to be sure that if viewers were triggered by the talk, they could be directed to the right resources to get help.

To date my TED talk has over 1.8 million views and has been translated into 39 languages. Many of my students did indeed see it, but I never had to deal with any negative repercussions in or beyond the classroom because of my choice to be vulnerable and transparent. I was reappointed (twice) at the GSB and now hold a senior leadership role at Stanford's Knight-Hennessy Scholars program. It all worked out. I've even started working on my next book dedicated just to this subject. My working title is The Bridge Back to Life: How One Man Came from the Edge of Death to the Center of Life.

My own lived experience sourced my five tips in this section, from checking my motives, seeking the counsel of my husband and advisors, to preparing for the consequences. Over the years, when others come to me and say, “JD, I just don't know that I can share this,” I respond much as Chris Anderson did when I was making my decision: If you're not sure, you may not yet be ready. Check your motives and know why you are disclosing before you attempt to take action. But if you do, be sure you're not doing it for your own self-motivated reasons. Disclose personally for the benefit of others.