CHAPTER 8

GOVERNMENT AS ACTOR

AND AS INSTITUTION

Collaboration has become a popular idea touted by governmental and nongovernmental actors alike as a means to foster better environmental management through decentralization and public involvement. Although numerous studies have focused on collaborative environmental management, none have explored systematically the role of government in these processes. The six case studies of environmental planning processes and outcomes presented in this book provide greater insight into collaborative environmental management. Using a consistent set of factors to guide this inquiry, the case chapters explored how government as actor and as institution affected collaborations across situations where government took the lead, encouraged collaboration, or followed the efforts of nongovernmental actors.

IMPACT OF GOVERNMENT

Governments can play many roles in collaborative environmental management. In the cases examined, government participation and commitment helped shape the formation, functioning, and maintenance of collaborative endeavors. As actors, government personnel often took the role of stakeholders and frequently were just one voice among many. These individuals sometimes acted independently of their governmental agencies. At other times, they served as agency representatives, and thus the roles they played as actors in the process were bounded by institutional mandates and forces. As a set of institutions, government established rules and norms that influenced many facets of collaboration. Each case in this volume examined the ways that government as actor and as institution influenced issue definition, resources for collaboration, group structure and decision-making processes, and collaborative outcomes. Cross-case analysis of these factors provides a basis for understanding how governmental actors and institutions leave their mark on collaborative environmental management.

Issue Definition

Issue definition refers to the biophysical scale and the way that a particular problem is framed. Together, these two elements of issue definition provide a rationale for action and a foundation on which collaborative initiatives are built. In instances where government encouraged or led the collaboration, governmental institutions established the biophysical scale of the collaborative efforts (see Table 8-1). In the cases of the Ohio Farmland Preservation Planning Program (OFPPP), Albemarle–Pamlico Estuarine Study (APES), and Animas River Stakeholder Group (ARSG), institutional stipulations required that funds be spent on planning focused at a particular scale (county, estuary, and watershed, respectively). In the case of habitat conservation plans (HCPs), federal institutions did not specify the scale, either in funding HCPs or in other rules governing the process. Thus participants could conceptualize HCPs at any scale within the habitat of a threatened or endangered species. But because federal officials provided technical assistance, based on scientific evidence about habitat extent, government influenced the biophysical scale of the collaborative planning effort in the form of actors, not institutions. In the Applegate and Darby cases, tensions existed between institutional conceptualizations of the appropriate management scale and the views maintained by governmental actors. With Applegate, for instance, the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) were organized into discrete units that reflected structural decisions made many years earlier within these agencies. The existing structures did not facilitate interagency coordination at the scale of a watershed, even though many governmental actors believed that this was the appropriate management unit. The result was that agency officials associated with the partnership held a different view of the appropriate biophysical scale than what was being advanced by their institutions.

Table 8-1. Summary of Governmental Impact on Issue Definition

Biophysical scale |

Issue framing |

|||

Case study |

Actor | Institution | Actor | Institution |

Applegate |

BLM and Forest Service personnel worked to manage resources at watershed scales |

Forest Service and BLM organized into non-watershed-based management units |

Forest Service and BLM personnel framed issue as need to increase public participation, reduce conflict, and undertake ecosystem management |

Forest Service and BLM reinforced hierarchical and segmented approaches; federal rules allowing Partnership One to be appealed led the group to broaden its issue focus |

Darby |

Governmental actors viewed scale as ecosystem rather than political jurisdiction |

Little impact, although scale coincided with existing HUA government program |

Governmental actors framed issue as problem with institutional water management practices |

Little impact: Partners broadened issues beyond traditional government focus |

HCP |

FWS personnel advised how much habitat each HCP should cover |

Little impact, as HCPs can cover a subset of habitat area |

Local and state governmental actors (like private actors) developed HCPs as means to comply with federal endangered species rules |

Federal ESA and implementing rules framed issue as need to protect listed species and their habitat |

OFPPP |

No impact |

State program set scale based on county boundaries |

No impact |

State program framed issue as need to encourage collaborative approach to farmland conservation; local governmental zoning rules affected feasible alternatives |

APES |

Federal and state actors in Policy Committee helped refine aspects of estuary focus |

Federal program set scale as estuary |

State and local governmental actors in Policy Committee helped frame issue as need to reduce scientific uncertainty through collaborative effort |

Federal program framed issue as need for greater collaboration and ecosystem approach to protect threatened estuaries |

ARSG |

State and federal governmental actors set scale at the watershed level |

WQCD set scale as watershed to match UAA requirements in federal law and state regulations |

Federal and state actors argued that Superfund designation could be avoided by taking a collaborative approach to watershed management |

Clean Water Act required use designation; federal Superfund regulations framed unappealing alternative to collaboration |

Similarly, the cases demonstrate that the way an issue is framed by governmental institutions is not always aligned with the way it is framed by affiliated governmental actors. In both the Applegate and Darby Partnerships, institutional pressures reinforced ingrained management practices. Nongovernmental actors were free to take an alternative stance, asserting that management practices should be directed toward an ecosystem scale and that the issue should be reframed as a problem with highly fragmented approaches to forest or watershed management promoted by the prevailing institutions. By embracing this problem definition, the governmental actors who participated in these collaborations, at times, placed themselves at odds with or went beyond their institutions.

In contrast, in the government-led and government-encouraged collaborations, government institutions and actors were more closely aligned in their views and actions. The HCP program, for example, provided explicit parameters for acceptable HCPs. Rather than take independent action and initiative, federal officials implemented the program by granting permits only to those applicants whose plans fell within these parameters, though the officials still had discretion to recommend that HCP participants consider certain things within these parameters. Governmental actors also demonstrated independence in some instances as they refined and extended the way their institutions framed the problem. For example, in the case of the ARSG, federal regulations established a basis for Superfund designation. Rather than support the adoption of this designation, governmental actors promoted the formation of the collaboration as an alternative means for improving water quality in the Animas River.

Resources for Collaboration

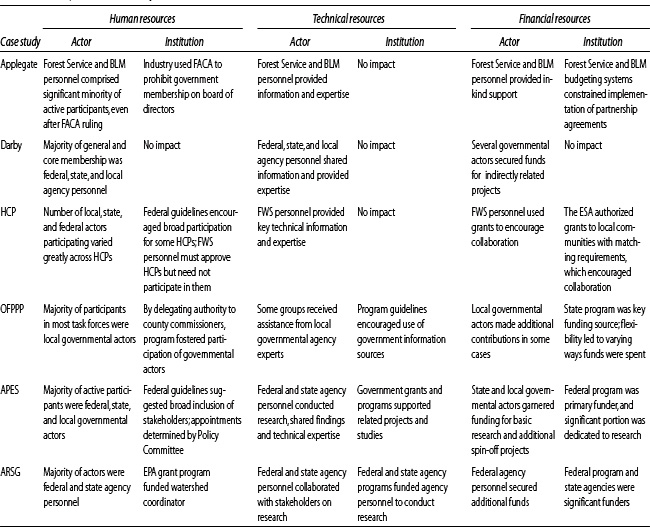

Other investigations and discussions of collaboration have emphasized the importance of resources, particularly funding and human capital (e.g., Wondolleck and Yaffee 2000; Steelman and Carmin 2002). The cases in our analysis suggest that such resources are important for sustaining an initiative over time and can determine what outcomes realistically can be accomplished. Regardless of their role, governmental actors and institutions influence the availability and character of human, technical, and financial resources in these endeavors (see Table 8-2).

Table 8-2.Summary of Governmental Impact on Resources

Human Resources. Human resources consist of personnel and the capabilities that they bring to the collaboration. Participation in the collaborative endeavors described in this book ranged from small groups consisting of 9 individuals in one OFPPP task force to 600 participants at the first public meeting in the APES process. Voluntary and paid staff participation are central to collaboration (Wondolleck and Yaffee 2000), with governmental actors often being significant human resources for the group.

Governmental institutions can, but do not always, influence the makeup of the collaborative group and the degree to which agency personnel are involved. In all of the government-led and government-encouraged cases, institutions in the forms of agency processes, programs, and official guidelines established the rules for membership selection and determined the degree to which governmental actors could become involved in the collaboration. At one extreme is the APES case, where the National Estuary Program (NEP) established a collaborative structure and made recommendations about the inclusion of specific groups of stakeholders. At the other extreme is the ARSG case, where agencies delegated membership selection to the group.

In most of the government-led and government-encouraged cases, governmental actors formed the majority of collaborative group membership. Governmental actors were present and active in the government-followed cases to varying degrees. In the Applegate case, they made up a minority of the participants. The composition of the general membership was somewhat fluid, as individuals from diverse stakeholder groups elected to come and go as they deemed appropriate. In the Darby case, governmental actors constituted three-fourths of the general membership and about two-thirds of the core group members.

Governmental actors are embedded in the institutions that they represent. As a result, their participation in collaborative environmental management initiatives can be constrained by policies, procedures, and politics. The impact of institutions on governmental actors was clearly seen in the Applegate case, where personnel from the Forest Service and BLM serving on the partnership's board were forced to resign from their board positions because of concerns over the Federal Advisory Committee Act.

Technical Resources. Technical resources refer to information and knowledge about the natural resource and its management that are available to the collaboration. In the government-led cases, governmental institutions provided a foundation for technical support. In the APES case, agency programs funded technical studies, whereas in the ARSG case, federal and state agencies funded government personnel as well as technical studies to conduct research. Similarly, in the OFPPP, a government-encouraged case, the program established guidelines that encouraged task force participants to use governmental information sources. In the HCP case, also government-encouraged, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) published technical guidelines for HCP participants. In contrast, governmental institutions had less impact on the availability of and emphasis placed on the use of technical resources in the government-followed cases.

Although the roles of institutions in providing technical resources varied greatly, individual governmental actors played consistent roles across the cases. In all instances, they provided technical knowledge and information that helped the collaborative groups work toward their goals. Government representatives provided the ARSG with water quality data and understanding of chemical processes, state and federal agency technical staff conducted research for APES, and agency representatives provided technical advice and assistance to the Applegate and Darby Partnerships. In the HCP process, federal officials used technical resources not only to achieve goals, but also as a means to promote collaboration itself, by framing a collective-action problem based on information about the distribution of habitat and knowledge about the causal mechanisms of extinction. Finally, in some of the OFPPP task forces, governmental employees, especially local government officials, provided technical information about farmland and land-use planning.

Financial Resources. Financial resources consist of the funding that a collaborative environmental management initiative receives or is able to generate. Governmental institutions established the basis for the disbursement of financial resources in all of the government-led and government-encouraged cases, with each drawing from different combinations of federal, state, and local funding. The financial resources also were distributed in different ways. In some cases, government provided funds for planning but not for implementation, as in the OFPPP and APES. Distribution of government funds also may be tied to formal matching grant requirements, such as in the OFPPP (100 percent local match of state funds), APES (25 percent state match of federal funds), and HCP (variable matches). In the government-followed cases, institutional impacts on funding differed. In the Darby Partnership, governmental institutions had no impact on funding, whereas in the Applegate Partnership, the lack of financial support from the Forest Service at times hindered the ability to implement agreements.

Governmental financial resources can benefit collaboration by facilitating research, covering operating expenses, supporting staff, and creating plans. Although the quantity of financial contributions is certainly important, the cases suggest that governmental actors also exert substantial influence by controlling the collaborative effort's use of funds. In the OFPPP, the state of Ohio provided financial support for the task forces but placed few limitations on their activities and use of funds. Consequently, how these funds were used, and what they accomplished, varied greatly across groups. In contrast, a significant percentage of the funding received from the government for APES was dedicated to research. As a result, nongovernmental participants had little influence on the degree to which research versus nonresearch activities could be supported. Although the presence of substantial levels of funding for research was useful, some participants were frustrated at the lack of support available for management actions. At the same time, governmental actors in all of the cases helped locate and secure additional financial or in-kind resources. As with human and technical resources, governmental actors may be constrained by their institutions, but they may exercise some discretion toward supporting and sustaining the collaboration financially.

Group Structure and Decision-Making Processes

Group structure refers to the ways in which the activities of members are organized and administered. Structure influences collaborative processes not only by shaping interactions, but also by establishing a framework for coordinating activities. In the government-led and government-encouraged cases, governmental institutions defined parameters for the way the collaborative had to be organized (see Table 8-3). In the APES planning process, the NEP recommended several model committee structures and what types of stakeholders should be included in the membership. The ARSG was required to form a single stakeholder group, the OFPPP was organized around task forces, and HCPs were oriented to planning groups. In these cases, institutions provided a general framework for the group structure but then granted autonomy to the groups to determine many aspects of the membership and internal organization.

Scholars suggest that collaboration should provide equal, if not greater, opportunities for nongovernmental actors to participate in and influence decision making (Gray 1989; Mandell 1999; Milward and Provan 2000). The case studies suggest that governmental institutions play an influential role in how decision making is structured. Although it is clear that collaborative approaches afford new opportunities for involvement, governmental institutions still define how the participatory process will unfold and the extent to which power and influence are shared. In all of the cases, institutions determined the degree of policy authority that was held by the collaboration. Similar to traditional approaches to participation, opportunities were granted for input, but in most cases authority was not delegated and decisions were not binding.

Table 8-3. Summary of Governmental Impact on Group Structure and Decision Making

Structure |

Decision making |

|||

| Case study | Actor | Institution | Actor | Institution |

Applegate |

Forest Service and BLM personnel shared leadership with other members of partnership |

Little impact, although FACA did require federal personnel to step down from formal leadership positions |

Forest Service and BLM personnel had same influence as other stake-holders; encouraged informal process |

Federal laws and regulations gave no policy authority to the group |

Darby |

Governmental actors followed NGO leadership |

No impact |

Governmental actors had same influence as other stakeholders; encouraged informal process |

Existing laws and policies gave no policy authority to the group |

HCP |

Leadership varied, with some HCPs led by private actors and others by local or state actors |

FWS guidelines gave discretion to private actors and local and state governmental actors in designing group structures |

Little influence by federal governmental actors; local and state actors had great influence in those HCPs for which they led the planning process |

HCP regulations and guidelines delegated authority to private actors and local and state officials to develop and implement plans; once a permit is issued pursuant to the plan, the plan bears legal obligations |

OFPPP |

Local governmental actors assumed leadership role in many task forces |

State grant program did not specify structure;allowed local flexibility |

Local governmental actors played key role in some task forces |

State grant did not specify decision processes;decisions were nonbinding |

APES |

Governmental actors on Policy Committee participated in final decisions on structure |

Federal rules mandated general committee structure |

Governmental actors were dominant on Policy Committee and TAC but not on CACs |

Program delegated authority to the group to develop plan; left decision processes flexible; granted no policy authority to implement plan |

ARSG |

State and federal actors shared leadership and responsibility for establishing formal committee structure |

Federal and state institutions encouraged stakeholder group formation but did not specify structures |

State and federal actors had same influence as other stakeholders |

No institutional specification of decision-making processes; ARSG was to recommend water quality standards to agencies with authority |

The cases illustrate a wide range of contributions by governmental actors to moderate the impact of institutions on decision-making processes. Various governmental actors implemented, interpreted, extended, and confronted existing institutional mandates and perspectives. Many of them demonstrated independent thought and action and influenced both group structure and decision-making processes. Across the cases, even when governmental actors were the leaders and when institutional parameters placed limitations on the policy authority of group decisions, these individuals often mediated institutional influence by working to foster genuinely collaborative efforts. With the exception of the APES case, these efforts made it possible for stakeholders to have relatively equal levels of input and influence in group decision-making processes. In the ARSG, for example, governmental and nongovernmental group members alike participated in establishing the water quality standards for the watershed. It appears that the key to making the transition from traditional forms of participation to truly collaborative styles of environmental management may be rooted in the way decision making is enacted and the degree to which power and influence are distributed between governmental and nongovernmental actors.

Collaborative Outcomes

In the environmental arena, the process of collaboration is important, but achieving outcomes is essential. For some practitioners and researchers, collaborative environmental management holds the promise of better environmental solutions through the early and ongoing input of multiple stakeholders. For others, the social outcomes of collaboration are just as important, because the hope is that they will enhance social capital and civic discourse to strengthen democracy.

Because of the limited number and types of cases, our analysis does not indicate whether collaboration is more or less likely to achieve better outcomes than other approaches to environmental management. Further, the time frame is too short to evaluate the long-term ecological outcomes of these collaborations. The cases do, however, illustrate some of the environmental and social outcomes that can result from these and similar types of collaborative efforts (see Table 8-4) and provide insight into the various ways in which governmental actors and institutions affect these planning processes.1 For example, HCP collaborators were required to implement the plans they designed as a condition for receiving incidental take permits, and members of the Applegate Partnership completed restoration projects.

Table 8-4. Summary of Environmental and Social Outcomes

Case study |

Environmental outcomes |

Social outcomes |

Applegate |

Restoration projects; alternative approaches to traditional land management |

Increased social capital; new spin-off community groups tackling variety of problems |

Darby |

Environmental education;new information; new cooperative projects;more proenvironmental behavior by governmental actors |

Forum for discussion and learning about other perspectives; increased collaborative capacity |

HCP |

Creation and implementation of HCPs, incidental take permits, implementation agreements, and a wide variety of conservation activities |

Increased trust among participants on successful HCPs, with collaborative capacity carried over to other collaborative efforts in one documented case;reduced legitimacy of the ESA among some environmental groups |

OFPPP |

Plans with varying sophistication across the counties; public education about farmland preservation |

Most counties built new social networks and encouraged community discussions to address issues |

APES |

Plan development; basic research; spin-off projects |

Improved networks and coordination but increased conflict and distrust among some participants |

ARSG |

New standards; new restoration projects;improved fisheries; improved water quality |

Increased trust and understanding among diverse participants; denser social networks; created sense among some citizens that decisions were not legitimately community based |

Environmental Outcomes. The environmental management activities in the cases centered largely on planning, but they also included monitoring, implementation, and enforcement. In addition, activities included standard setting, research, analysis, and education. For example, the OFPPP and APES created natural resource plans, the ARSG established water quality standards, and the Darby Partnership provided education on watershed management. In addition to its restoration efforts, the Applegate Partnership used meetings and outreach activities to address a wide variety of issues, including county-level land-use planning and agricultural and small-business development.

The internal dynamics of collaboration pose challenges to participants and place limitations on what the initiatives realistically can achieve. Most of the collaborative initiatives studied here satisfied their mandates and produced acceptable environmental management tools. Although the evidence is anecdotal, many of these initiatives appear to have produced tangible and consequential environmental quality changes. The Applegate Partnership promoted changes in forest management practices and ecosystem restoration projects. Participants in the Darby Partnership maintain that the education they received altered their behaviors and limited their negative impacts on the ecosystem while in APES, basinwide planning has been implemented. In the ARSG, in addition to establishing new standards, research findings helped target remediation efforts. Preliminary evidence from this remediation work suggests that there have been improvements in water quality and the fisheries in the watershed. Although we cannot demonstrate from any of these case studies that collaboration leads to particular environmental quality outcomes, it is apparent that collaborative activities can produce environmental management tools and promote environmental change.

Plans, standards, and educational activities are essential aspects of environmental management. Although the cases suggest that collaborative endeavors can achieve their goals, they also raise questions about the extent to which collectively generated recommendations, plans, and standards provide an appropriate foundation on which environmental management practices should be built and sustained, particularly as the quality of these outcomes was highly variable. Similar to challenges that arise with traditional approaches to environmental protection, a number of the groups had difficulty satisfying their mandates in the time period allocated. In the case of collaboration, this may be a reflection of the challenges of achieving agreement, let alone consensus, as well as the additional time required when participants lack expertise and experience. The OFPPP case suggests that the participation of diverse stakeholder groups contributed to a high level of variation in plan quality, and members of the ARSG found that the standards they developed were not as acceptable to regulators as to local stakeholders.

Social Outcomes. Although creating changes in environmental quality and management is the motivation for most collaborative environmental management endeavors, another consequence of these activities is that they can generate social outcomes which, in turn, are expected to indirectly influence future environmental outcomes. Social outcomes such as trust, enhanced communication, and improved policy awareness have previously been attributed to collaboration (e.g., Wondolleck and Yaffee 2000; Cortner and Moote 1999; Beierle 1999). Across the cases studied here, relatively consistent social outcomes emerged, including the building of trust, increased knowledge and understanding, network ties, and enhanced communication among different stakeholder groups. As a result, many of the cases, including Applegate, the ARSG, and the OFPPP, showed that collaborative efforts generated good relations and provided a first step for developing new and enduring partnerships.

Social outcomes such as new network ties, enhanced communication, greater knowledge, and better understanding of the policy process all suggest that collaborative environmental management can promote participatory democracy and deliberative practice. For example, in the Applegate Partnership, citizens and agency officials had been in conflict. In coming together, they began to learn about their differences in perspectives, and in the process, they were able to promote genuine communication that ultimately led to cooperative efforts. Similarly, members of the Darby Partnership, APES, and the ARSG reported that they developed greater insight into, and respect for, each other's views. Through the process of open and engaged exchange, these and other groups have been able to foster awareness of multiple perspectives and use them to make informed decisions.

Although collaborative participants expressed many positive sentiments related to the social outcomes of collaboration, feelings about collaboration were diverse, even within a given case. Some participants in the OFPPP reported that they were encouraged by the process and would participate in future collaborations, but others were far less enthusiastic. In the APES case, numerous participants were disappointed with the outcomes of collaboration and maintained that they now had a more realistic—and pessimistic—understanding of how policy processes work. This case shows that democratic practice can be enhanced through collaboration, but when participation takes place without empowerment or authority for implementation, it also can undermine trust in the system.

By focusing on governmental roles in the case studies, this analysis demonstrates that collaborative environmental management can alter the balance of power between communities and government officials. For example, the Applegate Partnership changed the nature of relationships between community members and governmental agencies. By promoting meaningful dialogue, members of the partnership were able to overcome conflict and promote working relationships and agreements. Similarly, members of the ARSG found that the process helped them understand and trust officials. Rather than resort to ingrained responses to each other, both community and government participants found that they were more open to each other's perspectives and, as a result, better able to respect and incorporate each other's views. By working in a collaborative fashion, the balance of power was altered to provide greater equity of input and influence. Such a result can have important “spillover” effects, fostering subsequent collaboration. For example, in the HCP case, collaboration in the Coachella Valley Fringe-Toed Lizard HCP built social capital that carried over to a larger, multiple-species HCP effort.

Governmental Impacts on Outcomes. The various environmental and social outcomes are linked to governmental roles. In all cases, governmental institutions and actors affected outcomes in important, though varied, ways.

As institutions, governmental mandates and guidelines substantially influenced environmental outcomes. For the government-led and government-encouraged collaborations, governmental institutions determined specific criteria or mandates that the collaborative effort was supposed to meet, such as the level of detail contained in plans, the final form of recommendations, and the authority (or lack thereof) to implement the plans (see Table 8-5). These institutions fostered collaboration in the four cases. Conversely, the lack of a mandate to work collaboratively in the two cases of government-followed collaboration constrained what the efforts were able to accomplish environmentally.

Across all six cases, governmental actors contributed to the efforts’ environmental outcomes by helping participants be innovative, providing information, securing resources, or carrying forward collaborative plans to be implemented. This is not to say that their actions always fostered greater environmental outcomes. In the APES case, for example, the focus of agency members on basic science may have distracted the program from producing information relevant for making on-the-ground environmental improvements. Importantly, governmental actors contributed even in the cases where government was following an effort developed by nongovernmental actors. For instance, the Darby Partnership encouraged governmental actors to incorporate watershed management concepts into their ongoing management programs. Additionally, governmental actors across the cases served as key voices for the agencies and institutions they were representing, as well as conduits between the collaborative efforts and those agencies and institutions.

Table 8-5. Summary of Governmental Impacts on Environmental and Social Outcomes

Environmental outcomes |

Social outcomes |

|||

| Case study | Actor | Institution | Actor | Institution |

Applegate |

Forest Service and BLM personnel helped create innovative approaches to land management |

Agency structures designed to support traditional approaches to land management impeded collaborative projects |

Forest Service and BLM personnel Top-down approach limited increased community involvement development of social capital in public land management |

Top-down approach limited development of social capital |

Darby |

Federal, state, and local governmental actors provided information and fostered cooperative projects to restore watershed health |

Lack of formal mandate to participate limited outcomes |

Federal, state, and local governmental actors participated in discussion and learning |

Agencies allowed, and in some cases encouraged, participation by staff leading to better understanding among fellow participants |

HCP |

FWS personnel sometimes encouraged collaborators to adopt specific plan components |

Federal guidelines provided broad outlines of planning process and expected content of plans |

Some local, state, and federal governmental actors increased social capital and trust by bringing their expertise to the planning process |

Incidental take permits allowed economic activities where they would not otherwise be permitted under the ESA |

OFPPP |

In many task forces, local governmental actors provided resources that affected plan contents |

Program funding and guidelines shaped quality of data and analysis;local zoning influenced plan recommendations |

Local governmental actors in some task forces contributed to the development of new network ties |

Grant program promoted interaction among local stakeholders |

APES |

State governmental actors contributed to plan development and improved scientific understanding; actors’ focus on science may have prevented more substantive environmental outcomes |

Federal guidelines required comprehensive plan development but relied on local and state implementation |

State and local government actors promoted networking and coordination among other participants; created conflict between different levels of government |

The NEP promoted development of networks across governmental and nongovernmental actors |

ARSG |

Federal and state governmental actors ensured that data collection and regulations were relevant to government; participated in remediation projects that improved water quality and fish populations |

Federal regulations shaped final form of water quality recommendations |

Prevalence of state and federal actors in collaboration led to questions of legitimacy of effort; state and federal actors worked together with other participants to foster understanding, and working relationships |

Delegation of group formation, operation of stakeholder group without undue influence from institutions allowed social capital to flourish |

Governmental institutions left their mark on social outcomes. In the two government-followed cases, the perceived inadequacy of governmental institutions was what spurred nongovernmental actors to initiate collaborative efforts. The Applegate Partnership experienced continuing institutional barriers that limited social outcomes, such as community-wide trust of the agencies. The Darby Partnership enjoyed changes in agency norms that allowed or encouraged staff participation in the collaborative effort, which facilitated the building of understanding among participants.

Institutions played a somewhat different role in spurring collaboration in the remaining cases. For the HCP program and the ARSG, the desire to avoid existing governmental institutions—Endangered Species Act prohibitions on taking listed species and Superfund designation, respectively—provided a strong incentive for stakeholders to try to work things out collaboratively. For APES and the OFPPP, a government program promising funding provided the major impetus for collaboration, spurring interactions among stakeholders who otherwise might not have communicated. In these four cases, governmental institutions not only spurred collaboration, but also drove issue definition, which affected the breadth of stakeholders who worked together. One of the government-led cases, the ARSG, is notable because although it represented a high degree of governmental leadership, in practice the governmental agency delegated facilitation to reduce its impact and allow social capital to flourish.

With ubiquitous governmental actor involvement in the collaborative efforts, it comes as no surprise that these individuals had substantial impacts on social outcomes across the cases. In the government-followed cases, governmental actors facilitated collaboration through efforts to increase community involvement, even in the face of institutional barriers that made this difficult (especially the Applegate case), or by their willingness to participate and learn from open discussions (highlighted in the Darby case). In a number of cases, governmental officials increased social capital and trust by bringing their expertise to the collaborative efforts, including scientific understanding (as in the HCP and ARSG cases) and regulatory knowledge (especially the ARSG and Applegate cases). In several instances, governmental actors provided the group with access to key networks beyond the group, as well as new networks with fellow group members that persisted outside the collaborative effort. At the same time, governmental actors’ roles sometimes harmed social capital. For instance, because the ARSG community of government personnel worked largely with each other, this led to perceptions of low legitimacy among some citizens. With APES, the confluence of diverse federal, state, and local governmental actors led to conflicts both among government actors and with nongovernmental participants.

PATHWAYS AND VARIATIONS IN GOVERNMENTAL INFLUENCE

Across all six cases, government personnel participated in the collaborative efforts and demonstrated individual levels of commitment. Because of their institutional ties, however, government personnel varied in the level of independent action they could take, including the extent to which they comfortably could maintain positions that were distinct from prevailing institutional norms. At the same time, governmental institutions had a significant and pervasive impact on all of the collaborative endeavors. Consequently, these institutions not only limited the autonomy of governmental actors, but also extended across all aspects of the processes and outcomes of the collaborations studied. The cases examined here represent a range of activities along a spectrum from government-followed to government-led collaborations. Even though governmental institutions made their mark on all of the collaborations, the extent of this imprint depends on where a case is situated on this continuum.

Government as Follower

In both the Applegate and Darby cases, government participated actively, though not as conveners of the collaboration. The Applegate Partnership formed in response to the spotted owl crisis and timber harvest injunction in the Pacific Northwest. An individual who recognized the importance of having industry, interest groups, governmental agencies, and area residents work together to manage the Applegate Valley spearheaded the partnership. Governmental agency members assisted with meeting facilitation and contributed time and other resources. Throughout the process, governmental actors served as both official representatives and interested individuals, assuming leadership roles at times and acting as engaged participants in other instances. Although highly collaborative, the Applegate Partnership was not without its conflicts and power imbalances, particularly because federal land managers had decision-making authority, expertise, and financial resources. Nonetheless, government actors generally shared the vision that collaboration would lead to better outcomes for everyone in the Applegate Valley. This perspective helped foster a “culture of good faith participation,” with agencies, organizations, and individuals adopting a problemsolving perspective. At the same time, governmental institutions were wedded to traditional approaches to forest management and organized in ways that made coordination difficult. The result was that, although individual governmental actors were responsive to community concerns and local residents were attentive to the constraints and needs of the agencies, tension between actors and institutions characterized this collaboration.

By contrast, the Darby Partnership involved governmental actors as participants in a more limited way. In this case, a nonprofit organization, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), approached a variety of stakeholders and encouraged them to work together to address environmental issues in the watershed. TNC typically purchased land to promote conservation, but the area was too large for acquisition, so the organization tried a different tactic: inviting governmental agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and private landowners to join it in a collaborative venture dedicated to protecting the watershed. Although a nonprofit organization initiated and sustained the partnership, governmental agency members were among the most highly involved actors in the process. Rather than government serving as a catalyst for the process or using the meetings to promote a particular view, TNC provided a forum to disseminate information and to promote exchange and interaction among all parties, including government representatives. Although governmental actors did not take leadership positions, a wide range of agency representatives maintained consistent participation and were actively involved and highly committed to the watershed.

In both of these government-followed cases, we see a reversal of the stereotypical roles that characterize many public participation processes and interactions between government representatives and nongovernmental actors. The traditional approach to public participation is that governmental agencies create plans and policies and serve as enforcement agents. Along the way, organizations and individuals may be invited to provide input or attend information sessions. Many of the interactions that ensue between government and nongovernmental representatives often are characterized by conflict, contention, and distrust. The Applegate and Darby cases demonstrate several important alternatives to these approaches and styles of interaction.

First, the cases show that individual citizens and nonprofit organizations can be the initiators and facilitators of collaborative processes. In both cases, nongovernmental actors recognized a void in environmental practices that needed to be filled. Rather than see this as a point of contention, they took the initiative and developed a means through which collaboration could take place. Second, the cases suggest that governmental actors can benefit by participating actively in collaboration. Tensions still may be present between governmental and nongovernmental actors and between the collaborative group and governmental institutions. Government participation in these types of collaborations can, however, provide access to new information and other forms of local knowledge, and foster community support for agency activities. Further, these cases demonstrate that governmental and nongovernmental actors can work as partners, engaging in collaborative problem solving and cooperative exchange.

In both the Applegate and Darby cases, governmental inaction created a vacuum into which nongovernmental actors stepped, taking the lead and forging bonds with governmental actors. Although the efforts of governmental actors were constrained by institutional parameters, the influence of these institutions was relatively limited. This meant that there was more room for flexibility and creativity. Members of the Applegate Partnership developed a new conception of how public lands could be managed, and members of the Darby Partnership envisioned integrated watershed management. At the same time, the very absence of institutional commitments and mandates constrained the outcomes of collaboration. For instance, the Applegate Partnership sought to transform the governmental institutions that defined public land management, but because governmental actors within the partnership also were situated within the governmental institutions that participants sought to change, they were limited in their ability to carry out the plans they devised. Without a broader mandate to effect change, the Applegate Partnership was unable to execute its vision. Thus the presence and absence of governmental institutions creates opportunities as well as limits in cases where government follows the lead of nongovernmental actors.

Government as Encourager

Governmental actors and institutions can serve as catalysts that foster collaboration among multiple stakeholders. The HCP case provides an important vantage point for viewing how governmental incentives offset traditional regulatory approaches to environmental management. The Endangered Species Act (ESA) is the critical piece of legislation for protecting endangered species because it limits uses of habitat on both public and private property. The ESA reflects elements of a traditional command-and-control framework. The establishment of the HCP program, however, has afforded government officials a means for promoting collaboration. Developing an HCP offers landowners, resource users, and local and state governments the opportunity to obtain a permit that will allow them to do what is otherwise prohibited by the ESA—develop part of the habitat of a listed species—provided that the HCP specifies in advance how sufficient habitat will be protected to maintain the long-term viability of the species. Although collaboration is not required by the rules governing the program, collaboration may benefit those seeking a permit as they prepare and implement an HCP, particularly in instances where habitat crosses multiple private parcels and public jurisdictions. One way that agency officials promote collaboration is by providing technical assistance that demonstrates to permit applicants the nature of interdependencies and how applicants can benefit from collective actions such as pooling land and resources for a common preserve system. Financial assistance also serves as an incentive for collaboration, as federal funds typically are disbursed to collaborative HCPs. While the ESA is often viewed as an institution that places the federal government in its traditional command-and-control role, the HCP program under the ESA expands the government's role from simply writing and enforcing command-and-control rules to creating incentives for collaboration. The program also shifts government's role as an actor from one of enforcement agent to that of expert advisor.

The OFPPP is a second example of how governmental institutions can offer incentives to foster collaboration. This state-level program provided grants to counties with the requirements that they match the grant amount either with funds or in-kind contributions and establish a task force including stakeholders with a cross section of interests. In addition to funding, the state government defined the program's objectives and established the overall structure of the planning process. Although governmental institutions offered incentives for initiating the process by providing funds and some basic guidelines, the internal dynamics of the task forces remained flexible. The groups were self-organized, going about their activities in a variety of ways. Governmental actors on the task forces included local officials from counties and townships as well as conservation districts. They worked alongside a handful of citizens and nongovernmental organizations, especially ones with agricultural interests.

These two cases suggest that in government-encouraged collaborations, governmental institutions structure the general design of a program and determine funding criteria, such as matching requirements, as well as access to governmental actors. Although consistent with top-down approaches to environmental management, these types of collaborations offer some levels of flexibility in the way the efforts are planned and executed. In the HCP program, for example, groups were empowered to develop their own decision-making processes and structures, which might have included steering committees, advisory boards, or existing organizations such as councils of local government. In the OFPPP case, a governmental institution, the state grant program, provided financial resources and structured the collaboration but placed few limitations on task force activities. Government representatives on the task forces served as equal participants, however, assuming leadership positions in some instances. In both the HCP and OFPPP cases, government as institution supplied incentives for collaboration, and then government as actor helped sustain and implement a planning process. Governmental institutions instigated these processes and also delegated overall control to governmental participants, who aided and assisted rather than adopted the more traditional roles of leader and manager.

A clear distinction between the influence of governmental actors and institutions emerged in these cases of government-encouraged collaboration. Unlike the government-followed cases, in which governmental institutions had relatively little influence on how collaborative activities played out once under way, governmental institutions had significant impacts on the contours of the HCP and OFPPP programs. The patterns that emerged from the case comparisons suggest that government incentives do more than just spark collaboration; they may leave an institutional imprint on all facets of collaborative structure and action. This is a critical finding, because grant activities supported by governmental agencies often are perceived as relying on market approaches and consequently are thought to be a hands-off tactic. In contrast, the OFPPP program illustrates that the financial incentives used to promote collaboration were tied to guidelines about program design and goals. Likewise, incentives in the HCP program promoted participation as a means to avoid the regulatory hammer of the ESA, but once the support was accepted, collaborative groups had to conform to institutionally defined outcomes, even as they were empowered to select their own structures and decision-making processes.

Government as Leader

Governmental institutions and actors loomed large in their influence on the two cases of government-led collaboration. The NEP defined the issues and provided financial resources for APES. State and federal governmental actors along with marine scientists in the Policy Committee defined the issue so that they could focus on the reduction of scientific uncertainty in the watershed. This issue definition suited the Policy Committee well, but not the Citizen Advisory Committees (CACs). Access to the Policy Committee by the CACs initially was funneled through the Technical Advisory Committee (TAC), which was dominated by government actors, although later in the program this changed at the insistence of the CACs. Members of the CACs were frustrated with their inability to influence the overall issue definition of the estuarine planning effort, let alone the research agenda dominated by the Policy Committee and the TAC. Whereas governmental institutions established a basis for the collaboration, governmental actors controlled the way that issues were defined within the initiative and ultimately prohibited it from attaining more significant environmental and social outcomes.

The final case, the ARSG, demonstrates that a governmental regulatory agency can initiate and sustain collaboration without dominating the group decision-making process. In the early 1990s, the CWQD indicated that the quality of the waters in the Animas River could be improved. The CWQD decided that the agency could either impose new standards on the community or develop them by means of a collaborative process with local stakeholders. In electing the latter approach, the CWQD set out to initiate an agency-driven collaborative process. Local residents initially were skeptical of this idea, but they ultimately came to regard the proposed collaboration as a better alternative to the agency determining the standards unilaterally. In this case, government proposed the collaborative process and took measures to ensure that it would be developed and implemented. The stakeholder group included numerous representatives from federal, state, and local agencies in addition to representatives from local nongovernmental organizations. The ARSG also received funding and other forms of governmental support. Governmental actors were instrumental in initiating and sustaining the collaboration, but they also regarded themselves as participating stakeholders. Consequently, rather than rely on a traditional top-down approach to environmental management, the government participants were flexible, delegating authority to the stakeholder group.

Governments led both the APES and ARSG processes, but there were critical differences in the roles that government representatives played in each case. Government officials structured and coordinated most aspects of the APES planning processes. Local scientists generally supported APES, but the program had authority only to plan, so the implementation of APES rested with government. Similarly to APES, governmental actors formed and provided resources for the ARSG. To overcome initial resistance to the proposed collaboration, they acted in a way that appeared to be more coercive than participatory. Once the process was under way, however, government representatives in the ARSG relinquished control and participated as informed partners rather than retaining a dominant position. These cases provide further evidence of the variations in governmental roles in collaborative environmental management. Importantly, they also suggest that even in situations where the government has relied on top-down approaches, collaboration took root and replaced some aspects of these more traditional environmental planning and management processes.

CONCLUSIONS

Patterns from our cross-case analysis can be viewed in light of trends in citizen participation and governmental environmental management. Beginning in the 1960s, governmental agencies began to create alternatives to regulatory, technical, and bureaucratic approaches to environmental policy, planning, and management. Driven by societal expectations for improved environmental quality and citizen desires to have input into public decisions, policymakers expanded opportunities for public participation in environmental decision making. Many of these approaches relied on formal methods for disseminating knowledge and on public comment on pending plans and policies. This style of input met with criticism, however, being perceived as tokenism rather than an empowered form of participation (Arnstein 1969; King et al. 1998). In response, collaborative approaches to environmental management were adopted in the late 1980s and 1990s. The desire to move environmental management closer to affected communities and to incorporate community sentiments and views into decisions more fully, in combination with increased awareness that environmental issues span geographic, organizational, and institutional boundaries, has led many governmental agencies to perceive collaboration as an appropriate management option. At the same time, many private firms and nonprofit organizations have altered their positions, maintaining that cooperation rather than conflict will result in more productive outcomes.

The shift in focus from participation to collaboration places new demands on governmental institutions and actors. As an institution, government embodies the rules, norms, and strategies that establish the institutional context of collective efforts. Many of the cases demonstrate the sweeping influence that governmental institutions have on collaborative efforts. Governmental institutions leave their mark on how issues are defined, what resources are used or are available, the structure of collaborative processes, and the outcomes that these endeavors produce. In many instances, institutional provisions determine the timing of the process and the degree of authority granted to participants. For example, in the ARSG, a governmental mandate served as a catalyst for initiating the group and established a time line for the project. Although the state agency ultimately could reject standards the ARSG created, the group did have the authority to recommend standards. Similar provisions and constraints were present in the OFPPP. In this situation, the agency program determined the time frame for the development of the plans and established basic guidelines for which issues the plans had to include.

Institutional provisions in statutes and regulations establish whether collaborative decisions and recommendations will be legally binding. Collaborative groups were given policy authority in just two of our cases: the HCP program and the ARSG. In the HCP program, participants were given legal authority to both plan and implement HCPs, subject to the conditions of the permit for each HCP. Although similarly subject to agency rejection, the ARSG was charged with establishing standards. In the remaining four cases, collaborative decisions did not carry any legal authority. The APES case illustrates tensions between making recommendations and implementation. In this instance, the initiative was centered around the development of a management plan. Collaborative planning without the authority to implement left many people disappointed and disillusioned with the process.

Whereas some cases illustrate the restrictions governmental institutions can place on collaboration, others reveal how these institutions can serve as a key resource and the spark that ignites collaboration in the first place. In the HCP and ARSG cases, the threat of existing statutes and administrative rules was the catalyst. In the Applegate case, institutions were the source of conflicts that led to the formation of the partnership. The injunction that prevented federal timber harvest led to a battle among interest groups and generated a virtual stalemate in federal forest management. In response, the partnership was formed to create economic opportunities and reestablish federal land management activities. As these examples suggest, institutions can establish limitations as well as create opportunities.

Government-led and government-encouraged collaborative efforts appear likely to have access to more resources than do government-followed efforts. The case studies suggest that resource availability is tied closely to the institutional commitment of government to a given collaborative effort. At the same time, however, government-followed efforts have greater autonomy over the use of their resources, as governments play a less prominent role in determining their group processes and decision-making structures. This autonomy, combined with broader goals, can stimulate government-followed efforts to innovate with new projects, ideas, and practices. Thus government as an institution providing resources and structuring processes generates a series of trade-offs. On one hand, institutional rules may help move an initiative toward a tangible result within a bounded period of time, and resources may ensure that a project can endure. On the other hand, by placing limitations on participants, rules and the associated resources may constrain the potential a collaborative initiative has for heading in new directions and generating creative solutions to environmental problems.

The pervasive influence of institutions calls into question whether a change has taken place in the effort to move from participation to collaborative forms of environmental management. Although institutions may constrain processes and outcomes, the six case studies in this volume demonstrate that governmental actors may moderate the impact of governmental institutions. Governmental actors are tied to the agencies they represent. At the same time, they have opportunities to act in ways that can foster equality in power and influence among stakeholder groups. The roles governmental actors played and their influence in determining group structure and decision-making processes suggest that these individuals largely determine the character of the collaboration.

One way they do so is by their willingness to engage stakeholder groups. It is often assumed that collaborative environmental management is initiated and sustained by nongovernmental actors and developed only in response to conflict. But as the Darby case demonstrates, citizen-initiated collaborations are not always rooted in conflict. Even though frustrations and tensions were present, rather than serving as the basis for interaction, this collaboration was rooted in a desire to proactively manage environmental resources. Moreover, both the Applegate and Darby cases show that government representatives can be willing and responsive participants even when local community members initiate interactions. In contrast to the antagonistic posture that has come to characterize many relationships between nongovernmental and government actors, these cases demonstrate that both sets of actors can collaborate and use their diverse perspectives and skills to promote the achievement of environmental and social outcomes.

A second way that governmental actors affect the nature of collaboration is the point at which they begin to interact with nongovernmental actors or work across agencies. In general, traditional government-sponsored initiatives tend to invite involvement late in the process. Frequently, governmental experts draft a plan or develop a project, and citizens are invited to comment or offer input on the documents that have been generated. It has been argued that this approach creates barriers to collaboration (Cortner and Moote 1999; Meidinger 1997). The four cases of government-encouraged and government-led collaboration suggest that collaborative environmental management efforts rely on comprehensive participation by relevant stakeholder groups from the earliest stages of development onward. Further, the HCP, OFPPP, APES, and ARSG cases demonstrate that rather than impede collaboration, governmental actors can be the catalyst for these endeavors, constructively developing planning and management programs that encourage stakeholder involvement.

Previous studies (Gray 1989) maintain that genuine forms of collaboration will be based on equal partnerships among all actors rather than be dominated by a single stakeholder. In some of the cases examined in this book, governmental actors served as agents who routinely implemented and enforced institutional mandates or took control of the collaborative process. The APES case, for instance, illustrates how government personnel and scientists constrained the framing of the problem to one of scientific uncertainty, thereby limiting input from a broad range of stakeholders and dominating the process of creating the estuarine management plan. In other instances, however, such as the Applegate and ARSG cases, governmental actors not only exhibited independent action and framed issues in ways that were distinct from institutional perspectives, but also worked as equal partners with other stakeholders. The patterns in the cases suggest that governmental institutions have a pervasive influence on collaborative endeavors. At the same time, genuine collaboration can emerge when governmental institutions delegate decision-making authority and when governmental actors respond to institutional requirements while promoting equal influence among stakeholder groups.