China’s private equity market

Abstract:

A significant development in China’s capital market since 2009 is the rapid development of China’s private equity (PE) industry, which is closely related to the developing China Growth Enterprise Market. This chapter provides an overview of China’s private equity sector and explains why it took more than ten years to develop private equity in China. It compares foreign and Chinese PE firms in their performance, development and investment strategies, and explores how to develop a successful PE firm in China. The chapter also describes the main players of China’s PE field and their behaviors. China Sovereign Wealth Fund and RMB-denominated PE funds are also introduced. In addition, the problems of Chinese PE fund development and the government’s policies to manage the PE industry are discussed.

Recent development of China’s PE market

The development of China’s PE industry can be roughly divided into two stages. The first stage was before 2009, during which foreign PEs dominated the field with US dollar-denominated PE funds. The second stage is from 2009. It is Chinese RMB-denominated PE funds that now dominate the field.

It was foreign PE funds that brought the concept to China. In 2004, when Newbridge Capital, the Asian unit of TPG Capital, acquired a 17.89 percent stake of Shenzhen Development Bank for RMB 1.253 billion Yuan, Chinese investors were introduced to the concept of PE. That was the first time in China that a foreign investor had purchased equities of a Chinese bank, which shocked China’s capital markets. In the following year, when a famous American PE, Carlyle, tried to buy 85 percent equity of Xugong Group Construction Machinery, China’s largest maker of building machinery, the concept of PE once again caught the Chinese public’s eyes. Although Carlyle did not make the deal, due to public concern over economic security, PE investment became widely known to Chinese investors. These two events dramatically drove development of the PE industry in the mainland. Since 2005, PE fundraising in China has been more than $57 billion. In 2011, the PE funds in China raised RMB 422.478 billion Yuan in total. Their total investments hit RMB 254.281 billion Yuan, creating a new high in China’s PE market.

In the first stage, most famous global PE funds, such as Carlyle, KKR, and Blackstone, entered China. They raised funds abroad; invested in China; then exited (mainly by IPO) abroad. In the second stage, fast-growing Chinese personal wealth, loose monetary policy and lack of investment channels contributed to the fast development of China’s PE sector. In particular, the launch of China’s GEM in 2009 provided local PEs with a great exit channel in China. The very high P/E ratio of GEM drove China’s PE industry to reach its first peak. Some PEs even achieved more than 100 times return in 2 or 3 years. The life of a PE fund investment in China is normally 2 to 3 years, much shorter than that of Western funds, which is typically between 4 and 6 years. Most Chinese PE funds are IPO funds rather than buyout funds, which are popular in the Western PE industry. There is another important reason for the boom in China’s PE industry. China’s financial system makes it easy to finance SOEs, while a large number of small and medium-sized private firms often find it difficult to obtain financing. The great demand for financing of private firms provides great development potential and promising prospects for PEs. Since 2009, China’s PE industry has entered so-called all-people times, meaning that everyone talks about PE funds and wants to do PE investment. In 2010, Chinese local PE capital accounted for 67 percent of the whole industry in market value, while foreign PE capital accounted for 33 percent. But in 2007, Chinese PE capital had been only 18 percent of the market value. The main players of the industry include Chinese local governments, private firms, SOEs, foreign investors and Chinese listed companies. PE funds established by securities companies have become a significant phenomenon. In 2011, at least 22 IPOs in China involved PE funds established by Chinese securities firms.

In China, local governments have many favorable policies to encourage PE development and attract PE funds. Four cities, Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Shenzhen, are the main bases of PEs. Shenzhen is the southern center of PEs. According to Mr Sheng Bin (2012), a senior officer of the Shenzhen government, by 2011, there were 1895 PE management companies in Shenzhen managing PE capital of RMB 214.87 billion Yuan. Since there are too many PE funds, good investment opportunities or projects are becoming limited. So, competition between PE investments has been dramatically intensified. To compete for a good investment project or opportunity, some PE funds have developed a competitive advantage of value-added service. Creating value for the operating company after the PE’s investment has been a slogan and trend of China’s PE industry. Since 2011, the industry has experienced a turning point and entered a restructuring and cooling down period due to China’s poor economic performance and the global financial crisis. Many PE funds have started to take an exit strategy. The first Chinese PE investment cycle is approaching its end. But the PE industry still remains in its infancy in China.

Main players in China’s PE industry

Foreign PEs in China

China’s economic reform and growth provide foreign PEs with great investment opportunities. There have been two strategic opportunities for them in the past 10 years in China. The first one was in reforming SOEs. When China reformed SOEs to establish a corporation system from the late 1990s, there was a strong demand for capital, management experience and human resources. A huge opportunity thus emerged. Global PEs, such as Carlyle and KKR, entered China in the late 1990s. Some of them invested in China’s SOE reforms. For example, Carlyle Group, the famous global PE, entered China in June 2000. It focused on investing in SOEs. Carlyle has made more than 50 investments with an aggregate equity expenditure of $2.5 billion in China, the biggest single foreign PE investment. In 2005, it invested US$ 410 million in China Pacific Life Insurance for 24.975 percent equities. The investment was converted into a stake in its parent company, China Pacific Insurance, in 2007. When China Pacific Insurance was listed in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2009, Carlyle received about six-fold profits. Mr Rubenstein, the CEO of Carlyle, constantly says that the Chinese market today is more favorable for PE capital than most other markets, and even much more favorable than the US. He even visited China three times within 4 months. Carlyle is now starting to cooperate with Chinese local governments to establish RMB-denominated PE funds. In 2010 it cooperated with the Beijing municipal government for PE investments.

The second great opportunity is from Chinese fast-growing small and medium-sized private firms and from China’s fast-developing capital markets, particularly the launch of GEM in 2009. China has plenty of small and medium-sized private firms, which have a strong demand for financing. Investing in them and exiting in 2 or 3 years by IPO on China’s stock markets with considerable returns is not difficult. Carlyle’s failed investment in Xugong Group Construction Machinery, a large Chinese SOE, has caused Carlyle and other foreign PEs gradually to switch their favorite investment from SOEs to Chinese private firms. Chinese private firms could be a gold mine for foreign PEs. Goldman Sachs Strategic Investments (Delaware) L.L.C., part of the Goldman Sachs Group, invested in Western Mining (601168: SSE) for RMB 96.15 million Yuan in 2006. Three years later, in 2009, it received returns of nearly 100 times. Goldman Sachs Direct Pharma Ltd, which is also part of the Goldman Sachs Group, invested US$ 4.9176 million in Hepalink (002399: SZSE), a pharmaceutical company in Shenzhen, for 12.5 percent stakes in 2007. The return was 103.7 times in 4 years. KKR, the famous global PE, made its first investment in 2007 through its subsidiary Titan Cement. It invested $115 million in China Tianrui Group Cement Company Limited, a leading clinker and cement producer in China in terms of production capacity and production volume. Tianrui was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on 23 December 2011, and raised funds of HK$ 91.6 million. It can be seen that foreign PEs prefer to invest in Chinese traditional industries. That may be explained by China’s advantages in traditional industries. In 2010, the PE investment in food and agriculture industries reached $2.6 billion, three times that in 2009.

To explore investment opportunities in private firms, localization is becoming more important than before for PEs. To obtain local resources, a good choice for PEs is to cooperate with local giant companies. Carlyle is starting to partner with domestic entrepreneurs. In 2010 Carlyle teamed up with Fosun Group, one of China’s largest privately owned conglomerates, to sign a strategic cooperation agreement. They jointly sponsor a RMB PE fund of $100 million, which focuses on SME company investments.

It should be noted that the size of foreign PEs’ capital is not large: 46 percent of them are below $1 billion. Those whose capital size is between $1 billion and $4.9 billion accounted for about 30 percent of the total PE funds. But, some foreign PEs are developing fast in China. Beijing-based Hillhouse Capital, for example, which was established in 2005 with only $30 million from the Yale Endowment, now manages almost $6 billion, largely from top university endowments in the US, due to its great performance. Hillhouse has a record of 52 percent compounded annual returns since it was founded. In general, foreign PE funds perform well in China. IPO is a main and popular exit strategy in China. From 2009 to 2011, the exit through IPO increased more and more after the launch of Chinese GEM (Table 4.1). The exit value increased from RMB 3.64 billion Yuan in 2009 to RMB 19.46 billion Yuan in 2011. Foreign PEs’ IPO in China’s A-share accounted for 11 percent of the total.

Table 4.1

Foreign exit cases and value from 2009 to 2011

| Year | Exit cases | Exit value |

| (Yuan RMB, billion) | ||

| 2009 | 6 | 3.64 |

| 2010 | 13 | 19.9 |

| 2011 | 16 | 19.46 |

Source: ChinaVenture (www.chinaventure.com.cn)

Foreign PE investments’ return in China is tending to increase, while the Chinese PE market’s average return is tending to decline (Table 4.2). In 2009, the average book return for Chinese PE industry exiting through IPO on China’s main board was 13.8 times, while foreign PEs’ average book return in China was 6.9 times, which was much lower. However, in 2011, the average book return for the industry had declined to 7.6 times, while foreign PEs’ average book return reached 8 times. In the first half of 2012, foreign PEs’ book return exiting through IPO on China’s stock market reached 12 times, compared with 5.1 times for the Chinese PE industry.

Table 4.2

Comparing foreign PEs’ average book returns in China with Chinese PE industry performance from 2009 to 2011 (exit through IPO in Chinese main board)

Source: ChinaVenture (www.chinaventure.com.cn)

Foreign PE funds have advantages in management team and management experiences, while Chinese PE funds have the advantages of understanding Chinese conditions and rich local resources. Having realized their weaknesses, some foreign PEs, such as Carlyle, have started to localize their operations and develop good relations with local governments. Carlyle was the first foreign PE to set up an office on the mainland to handle public relations, strengthen communication with local media and reshape its corporate image in China. However, foreign PE funds face some restrictions on investing in China. They are not allowed to invest in some sensitive industries, or investment may be restricted. Their investments sometimes cause concern to the public and central government. For example, in 2007, Carlyle’s investment in Xugong Group Construction Machinery was rejected by the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). Carlyle also failed to invest in Guangzhou Development Bank and Chongqing Commercial Bank. The establishment of foreign PEs should obtain approval from the central government. In March 2009, the MOF decided that, for those PEs whose capital size was no more than $100 million, local approval was enough; approval from the central government was no longer necessary.

The PEs with local and central government background

Both Chinese central government and local governments support the developing PE industry. They have financed the establishment of many PE funds. Local governments normally have two ways of sourcing capital to establish PE funds. One is through fiscal budget; the other is to cooperate with national policy banks. On 28 November 2010, China Development Finance, part of China Development Bank, established a fund of fund, or FOF, in cooperation with Suzhou Industrial Park Government. The total capital is RMB 60 billion Yuan for 12 years, of which RMB 40 billion Yuan would be focused on investing in growing companies and RMB 20 billion Yuan on startup companies. The fund takes limited partnership and is registered in Suzhou City.

Some Chinese local governments have established guiding PE funds. Since 2006, local governments have established about 90 funds in 24 provinces; the total capital is more than $45 billion. They are FOFs and finance the establishment of PEs. The largest one may be the Beijing Private Equity Development Fund, established in September 2009, whose capital is about to be RMB 10 billion Yuan. Zhejiang Province and Jiangsu Province, where private economies and investments are very active, set up 21 and 13 PEs respectively. The quantity of PE funds ranks at the top two in the nation. In 2009, Beijing Government announced a “1+2+3+N” strategy to develop the PE industry. “1” means that Beijing Government would establish a guiding fund of RMB 10 billion Yuan. “3” means that, under the guiding fund, capital funds would be established for three industries, focusing on high-tech, green and cultural creativity industries. “N” means investment in many companies.

PEs established by SOEs

SOEs have a strong financial background with rich capital supply. Many large SOEs have their own investment companies or banks. Some of them have established PEs. On 28 December 2006, several large SOEs, including BOC International Holdings Limited, Teda Investment Holding Co., Ltd, China’s National Council for Social Security Fund, Bank of China Group Investment Limited, Postal Savings Bank of China Co., Ltd, Tianjin Jinneng Investment Company, China Development Bank Capital Corporation Ltd, China Life Insurance (Group) Company, China Life Insurance Company Limited, and Tianjin Urban Infrastructure Construction & Investment (Group) Co., Ltd, established the first industrial capital fund in China, which was named Bohai Industrial Investment Fund Management Co., Ltd, with registered capital of RMB 200 million. It is a pioneer of the Chinese PE industry, and unique in terms of strong support from Chinese government as a state-owned investment platform while operating in line with market practice.

Another important type of PE related to SOE are PEs established by insurance companies. Insurance companies have plenty of capital for investment (Table 4.3). However, they could not establish PE funds freely, and their involvement in the PE industry was restricted. In 2010, the CIRC issued “Interim Measures for the Administration of Utilization of Insurance Funds” and “Interim Measures on Investment of Insurance Funds in Equity” (PE Regulations), which provided guidelines and allowed Chinese insurance companies to invest in PE from September 2010. But there were still some restrictions. Each insurance company could invest no more than 5 percent of its total assets in direct equity investments in unlisted companies and no more than 4 percent of its total assets in private equity funds. But the aggregate of all such investments should not exceed 5 percent of its total assets. Under the regulations, insurance companies were only permitted to directly invest in insurance companies, insurance intermediaries, non-insurance-related financial institutions, and companies providing elder care, medical care and auto services that were closely related to insurance business. Furthermore, they were not allowed to use leverage. Also, investment in venture capital funds was prohibited. An insurance company was not allowed to set up a PE fund or a fund management company. In addition, the PE Regulations also require an insurance company to analyze and monitor the investment activities of PE funds in which it invests. In August 2011, China Life became the first Chinese insurance company to be granted a license to invest in PE.

Table 4.3

Insurance companies’ capital size for PE investment by the end of 2010

| Insurance company | Total assets (RMB billion Yuan) | Capital size for PE investment (RMB billion Yuan) |

| China Life Insurance (Group) Company | 1776 | 88.8 |

| PingAn Insurance (Group) Company | 1171.6 | 58.6 |

| China Pacific Insurance (Group) Co., Ltd | 475.7 | 23.8 |

| The People’s Insurance Company (Group) of China Ltd | 440 | 22 |

| New China Life Insurance Co., Ltd | 300 | 15 |

| Taikang Life Insurance Corp., Ltd | 300 | 15 |

| China Taiping Insurance Group | 136.8 | 6.8 |

| China Reinsurance (Group) Corporation | 101.6 | 5.1 |

| An Bang Property & Casualty Insurance | 25.7 | 1.3 |

| Huatai Insurance Holding Co., Ltd | 14.8 | 0.7 |

Source: ChinaVenture.

On 16 July 2012, the CIRC issued the Notice on Issues over Investment of Insurance Funds in Private Equity and Real Estate to insurance companies and insurance asset management companies, stating that Chinese insurance companies, by approval, can invest up to 10 percent of their total assets in private equity, including private equity funds and direct private equity. Insurers will be permitted to invest up to 10 percent of their total assets in private equity, compared with 5 percent previously. That would potentially unleash about $50 billion of fresh capital into unlisted firms. The CIRC has now allowed insurance companies to directly invest in energy companies, resources companies, modern agriculture companies relating to insurance business, commercial trade and distribution companies adopting new business models, which meet China’s intention to develop the energy, modern agriculture and commercial and trading industries and encourage investment in these industries. But, Chinese insurance companies are still not allowed to invest in venture capital funds and low-technology focused funds. They have yet to gain approval to invest in offshore PE funds. China Life Insurance has involved establishments of three PE funds as a limited partner (LP), and China PingAn Insurance Group involved two PE funds as a LP.

China’s local PEs

According to research undertaken by the Industrial Bank and the Hurun Report Research Institute, China currently has 2.7 million high net worth individuals (HNWIs) with personal assets of more than RMB 6 million Yuan, and 63,500 ultra-high net worth individuals (UHNWIs) with assets of more than RMB 100 million Yuan. Among HNWIs with a net worth more than RMB 50 million Yuan, 13 percent of them invest in PE funds. Drawn in by the attractive returns of PE, Chinese high net worth individuals have crowded into the PE sector for the past several years. Many local PEs have been established, such as NewMargin Ventures and Jiuding Capital. NewMargin Ventures was established in 1999 with RMB 60 million Yuan and managed $2 billion by 2011, including five RMB funds and one US dollar fund. It invested in about 90 projects, of which 28 have been successfully exited by IPOs. The average return for each IPO is about 11 times. According to AVCJ Research, RMB funds attracted more than $24 billion in 2011, twice the figure achieved by their US dollar counterparts. The local PE funds are large in numbers, while small in size. They understand China’s conditions well and perform very aggressively. For example, Jiuding Capital takes a very aggressive approach to searching for investment opportunity and establishing nationwide branches.

PEs established by securities companies

In China, some PE funds are established by securities companies. There are two such kinds of PE funds. One is directly established by securities firms. As early as in 2007, the pilot program of PE investment by securities companies was launched. Securities companies could use no more than 15 percent of their own capital to set up a PE fund for PE investments. But raising capital from the public and other investors is not allowed. Meanwhile, the maximum number of investors permitted in any one fund has been capped at 50. The China International Capital Corporation (CICC) was the first securities firm to be approved by regulators to set up a PE fund. The PE was of RMB 5 billion Yuan. It was the first PE fund in China to be managed by a securities broker. After that, more and more securities companies begin to develop PE business. Some securities firms expect the revenue from PE investments to be 20 to 30 percent of their total revenue in the near future. A total of 34 securities firms have been approved to launch PE funds under the pilot program, and the Securities Association of China estimates that investments have reached RMB10.2 billion or $1.5 billion. Under new guidelines issued by CSRC, securities firms can incorporate these PE operations into their regular businesses. Any qualified securities firm can apply to CSRC for a business license to set up a PE fund. By the end of May 2012, more than 20 equity investment funds, valued at RMB 60 billion Yuan, that had been established by securities firms were disclosed. The other type of fund is transferred from securities’ direct investment business. In the Chinese PE industry, those investment firms established by securities companies are often called the direct investment business of securities companies. Some of them are later transferred to be PE funds. Those PE funds play an important role in the PE industry, because of their relationship with securities companies, which often serve as underwriters in IPO business.

PE management

LP and fundraising

In China, LP can be divided into two groups according to the source of their fundraising: foreign LPs and domestic LPs. Foreign LPs are mainly overseas institutional investors, which carry out fundraising abroad. According to Zero2IPO research, the top foreign LPs are foreign university funds, donation funds, FOF and corporate annuities. They accounted for 22 percent, 18 percent, 12 percent and 12 percent of foreign PEs in China respectively. Most LPs have quite a small capital size: 77 percent of LPs contribute less than $1 billion, 25 percent of LPs give capital less than $25 million, and only 11 percent of LPs contribute capital of over $5 billion (Figure 4.1). The reason may be that LPs are still cautious about PE investment in China. In addition, 44 percent of LPs investments are between $50 million and $999 million. Domestic LPs are mainly local governments, listed companies, securities firms, SOEs, and private investors. Listed companies account for about 20 percent of LPs and are the largest sources of PE fundraising. Listed companies normally have four ways of becoming LPs:

![]() As a LP, the listed company provides capital for a PE.

As a LP, the listed company provides capital for a PE.

![]() A listed company establishes a branch or uses one of its departments to conduct equity investment.

A listed company establishes a branch or uses one of its departments to conduct equity investment.

For domestic investors, when they want to become involved in establishing a PE, they often face a difficult decision: whether to be a general partner (GP) or a LP. Since China’s PE is still in its infancy, there is a lack of PE professionals. Some investors would like to establish PE funds by themselves. When LPs select different PE types for investment, the research indicates that more than 62.3 percent of LPs make a growth fund their first choice; 56.3 percent of LPs prefer to choose PE investment in start-up companies; and 44.4 percent of LPs make buyout funds their priority (Figure 4.2).

When an LP chooses a type of PE fund, the top six issues that concern him are management team, PE connections in its industry, investment strategy, brand name, performance record, and corporate governance. The first two issues are the most important for LPs’ consideration. Unlike in Western markets, Chinese LPs always want to be involved in PE management, which often brings GP management troubles and thus causes conflicts between LPs and GPs. There are few LPs who are not involved in PE management in China. LPs are normally involved in PE management in three ways. One is that LPs have memberships in the investment decision committee of the PE fund. Another way is that LPs establish an independent consulting committee to supervise GPs’ management. The last way is that the investment decision committee is made up of representatives of both LPs and GPs for investment decision making.

PE fundraising in China is mainly affected by three factors: monetary policy, economic environment, and available investment channels. From 2011, China’s poor economic performance and increasingly tight monetary policy have made fundraising more difficult than before. Banks and financial institutions are becoming the main sources of PE fundraising. Noah Wealth, China’s largest third-party financial planning institution, has made its investment focus on the PE field. In 2011, 48 percent of its customers were involved in PE investment. In private banking, some banks provide their customers, who have plenty of capital, with financial products related to PE fundraising. Foreign LPs often face two obstacles in investing in China. First, taking capital into China is much easier than bringing it out, because China has a foreign exchange control policy. Second, according to the NDRC, a local currency vehicle containing foreign capital loses its local status and is treated as foreign investment. Then its investment is restricted and it cannot invest in some industries, such as local PEs.

GPs and fund management

Since 2009, high returns of the PE industry on the mainland have attracted many of the financial elite to switch to the PE industry and become GPs. Most of them are professionals from public funds, securities firms, investment banks, or accounting firms. The strong demand for GPs and the fast-growing PE industry cause intensive competition for financial professionals who are qualified to be GPs, particularly with a background in multinational financial institutions. In 2009 and 2010, each year at least 23 senior managers of Chinese branches of multinational financial firms at partner or general manager level resigned. They either joined the newly established PE funds in China as GPs, or established new PE funds by themselves in China. GPs in China are often asked to invest 10 percent to 20 percent of their own capital in the PE they manage, which is higher than in Western countries. Similarly to foreign GPs, they normally charge a 1.5 percent to 2 percent annual management fees on the overall fund commitments, plus another 20 percent bonus on profits.

Since China’s LPs always want to be involved in fund management, conflicts between LPs and GPs are unavoidable. According to Mr Zhang Lan, a lawyer of Jin Mao P.R.C. Lawyers, a famous law firm based in Shanghai, for the past several years there have been more and more dispute cases between LPs and GPs. It is said that at least 50 percent of PE funds have conflicts between LPs and GPs. In addition, it is not uncommon to see some LPs default on their commitments to GPs. But GPs dare not sue them because that will hurt their reputations. Some people describe the relationship between GP and LP in a PE as like that of husband and wife in Chinese families, in which the wife always wants to manage her husband in every way, and the husband often has to report everything to his wife.

Structuring PEs in China

In Western markets, limited partnership is the most popular way of establishing PE funds, mainly due to favorable taxation, while in China PE funds have three popular structures: limited partnership, investment trust, and corporation. Limited partnership has just started in China and has not been popular. The first limited partnership PE fund in China was Shenzhen Cowin Capital, which was established on 26 June 2007. Most PE funds take either investment trust or corporation structure. Most PEs’ institutional investors, such as SOEs and local governments, structure PE funds by corporation, because this way is well defined and protected by Chinese Company Law and Securities Law. Private investors prefer to take the trust route. There are two operation models for trust-based PE. One is that a trust serves as LP for fundraising, and cooperates with another institution that serves as GP. The other model is that a trust serves as both GP and LP. Limited partnership can bring favorable taxation benefits in Western countries; however, in China, taxation on partnership PE funds remains somewhat uncertain, which is the main reason for the lower popularity of limited partnership PE funds in China. From 1 March 2010, The Administrative Measures for the Establishment of Partnership Enterprises within China by Foreign Enterprises or Individuals issued by the State Council came into force. PE funds in China could then be established by partnership. In addition, there is another structure, the contractual type fund, which is a structure between corporation and trust. Bohai Industrial Investment Fund Management Co., Ltd is structured in that way.

PEs’ investment strategy

In China, most PE funds invest in operating companies. Some invest in public equity and are often called PIPE (private investments in public equity). Investing in M&A is not popular. Secondary funds have not been developed. By studying PE investments from 2007 to 2011, it can be seen that in China four industries received more than 100 investments from PE funds. They were the machinery and equipment industry, the chemical industry, the electronic industry and the information service industry (Figure 4.3). PE investment deals in these industries reached 253, 122, 118 and 110, respectively. In 2011, the PE investments in the four industries were 61, 56, 36 and 44 deals, respectively. For the past 5 years, the compound annual growth rates of investment in the machinery and equipment industry were 63.8 percent. Each Chinese listed company in machinery and equipment had at least two PE funds involved. Meanwhile, the home appliances industry, which was the most popular industry 5 years ago, had gradually been abandoned by PE funds. Some other industries, such as textiles and building materials, are also losing their attractiveness.

Figure 4.3 The top four Chinese industries receiving PE investments from 2007 to 2011 Source: ChinaVenture (www.chinaventure.com.cn)

It should be noted that, since 2010, the biological medicine industry and the clean technology industry have gradually become the favorites of PE funds due to government support. In 2011, investments in biological medicine reached $357.5 billion. Many PE funds believe that the great potential of the industry will be achieved in the near future. In 2012, the industries of consumption, medical services, environmental protection and TMT (technology, media and telecom industries) are also preferred by PE funds. In addition, in a PE’s investment agreement, the PE often asks to sign a repurchase clause with the operating company. That means that, if the operating company cannot successfully realize IPO, the company will repurchase the equities that the PE holds. The repurchase price is normally based on either net asset or compound growth rate of the company. The big price gap between Chinese primary and secondary stock markets makes IPO on Chinese stock markets, particularly on GEM and SMEB, which normally have much higher P/E ratios than the main boards, the target of most Chinese PE funds. So, a pre-IPO investment model has become popular, which is the investment in an operating company before its IPO. From July 2009 to March 2012, there were 780 IPOs in China. Of these, 432 received PE investments, and more than 700 PE funds were involved. The total number of PE investment deals was 1137 and their floating profits reached RMB 171.5 billion Yuan. About 10 percent of the PE investments received returns of more than 100 times. Sixty percent of the PE investments received returns of less than 10 times. It can be seen that ten percent of those 1137 investments were made 1 year before the IPOs; 40 percent of the investments were made 2 years before the IPOs; and 74 percent were made 3 years before the IPOs. A typical Chinese PE investment is a non-controlling stake of less than 10 percent in an operating company. Few PE funds controlled more than 20 percent equities of the operating companies. PE investment value has been as much as $1600 million (Table 4.4). It should be noted that, in PE investments, valuation adjustment mechanism or cliquet has been widely used by PE funds to reduce the risks of their investments.

Table 4.4

The top ten PE investments in value in 2011

Source: ChinaVenture (www.chinaventure.com.cn)

A PE fund normally has two ways to search for investing opportunities. One is by the PE itself according to its investment strategy; the other is by intermediaries, such as investment banks, accounting firms, etc. Since July 2009, many professionals switched from the intermediaries to PE funds. Thus, the PE funds have close relationships with the intermediaries. In investment, each PE has own policy of selecting investment projects. For example, NewMargin Venture has a four-step selection policy. In the first step, industries with high growth rates would be identified. In the second step, potential champions of the industry would be found. In the third step, the companies with differentiation advantages would be selected. In the last step, the PE would provide the selected company with value-added service. Each year, NewMargin Venture may analyze 3000 to 4000 candidate companies. On average, studying 300 companies may lead to one successful selection and investment decision.

Due to increasingly intensive competition in the PE field and poor economic performance recently, some PE funds are experiencing difficulty in finding an appropriate investment opportunity. They are starting to search for opportunities in secondary stock markets. Some PE funds involve the private placement or private offering of additional shares of listed companies. One of the largest local PE funds, Happy Silicon Capital Management, has invested in private placement for more than 30 companies since 2006. According to Mr Bao Yue, CEO of the company, its annual return on the investment was about 30 percent by the end of 2011. When Chinese stock markets perform poorly, PE funds often prefer to invest in corporate restructuring or M&A. But, some PE funds suffer serious loss in investment in private placement. In 2011, poor performance of China’s stock markets caused most PEs’ investments in private placement to lose money (Table 4.5). In 2011, PE funds invested in 82 private placements. Only 24 of them received floating profit, while 58 had floating loss. The investment return is determined by the stock performance, which is often uncertain and full of risks. For example, the PE investment in Star Lake (600866: SSE) had more than 55 percent floating loss by 19 December 2011 since the private placement finished on 22 April 2011, while Bohong Shujun, a PE based in Tianjin, received about 107 percent floating profit from its investment in private placement in Annada Titanium (002136: SZSE).

In future, with the New Third Board developed, secondary funds may be developed. Meanwhile, China’s poor economic performance is driving the development of some Chinese PE funds which focus on M&As. Another investment opportunity for Chinese PEs is in so-called orphan stocks. For the past 2 years, many overseas listed Chinese companies have been frequently sold short by some foreign research firms, such as Citron and Muddy Waters. These listed Chinese companies are called orphan stocks, because they may have been unfairly tainted by a raft of accounting and governance scandals. Then, many of those overseas-listed Chinese companies are looking to come home, where they can fetch much higher valuations than abroad. Taking the private companies to relist on China’s stock market offers an arbitrage opportunity for Chinese PE funds. Some PE funds are preparing buyouts of these orphan stocks. In addition, some Chinese PE funds, such as Hony of CITIC PE, are expanding abroad to search for investment opportunities in global markets.

PEs’ exit strategy

Exit through domestic IPO

PEs’ favorite exit strategy in China is through IPO, which accounts for over 70 percent of disclosed cases, while in developed markets such as the US it is only 10 to 15 percent. Other exit strategies, such as by secondary market, have not been developed in China. In 2011, China’s GEM and SMEB and the American NASDAQ are the favorite IPO choices for Chinese PE funds (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 The exchanges distribution of China’s IPOs in 2011 Source: www.chinaventure.com.cn

However, by IPO fundraising amount, HKEX, SSE and SMEB are the top three stock exchanges (Figure 4.5). According to China’s regulation, a company must have a sponsor, which is an investment bank, for its IPO application. Then, the cooperation between PEs and investment banks is critical for a PE’s IPO exit strategy. From 2009 to March 2012, there were 14 PE funds, which cooperated with eight investment banks more than three times in IPO. They cooperated 71 times in total for IPOs. There were 44 PEs, which cooperated with 14 investment banks more than twice. Behind each famous investment bank there is at least one PE. A popular cooperation model is called the sponsorship plus consulting model. It was first used by two famous securities companies, Guosen Securities and Industrial Securities. In the cooperation, a securities company serves as the financial consultant of the operating company with PE investment at first. Then, the investment bank serves as a sponsor of the operating company when the operating company applies for IPO, and helps the PE investment to exit through IPO. As the financial consultant, the investment bank or securities firm charges the PE a consulting fee, which includes two parts, the basic financial consulting fee and the investment consulting performance fee. The basic financial consulting fee is normally 1.5 percent of the capital that the PE receives; and the investment consulting performance fee is often 20 percent of the PE’s profits.

Figure 4.5 IPO financing volume of Chinese firms in different stock exchanges in 2011 Source: www.chinaventure.com.cn

Another popular cooperation model, which had been suspended by CSRC, was a securities firm direct investment model. In this model a securities firm invested its PE capital in an operating company, when it served as an underwriter of the operating company for its IPO. From 2009 to March 2012, 46 operating companies with nine securities firms’ PE capital successfully realized IPO. The securities companies received floating profits of RMB 4.348 billion Yuan. Now, the authority only allows one securities firm to invest in an operating company before the securities firm works on the operating company’s IPO; and no more than 7 percent of equities of the operating company can be invested by the securities firm’s PE. In China, although IPO needs approval from CSRC, most IPO applications are approved. When a company’s first IPO application is rejected, the company can apply for a second time, or a third time. In addition, easy IPO approval and high IPO P/E ratio attract many foreign PEs to change their operation from fundraising abroad and exit abroad to either fundraising abroad and domestic exit, or domestic fundraising and domestic exit. In 2011, although economic performance was poor, there were still 237 IPOs for the first 11 months. But the IPO P/E ratio decreased from 80 times at the beginning of the year to between 30 and 40 times.

Exit through overseas IPO

From September 2010 to May 2011, 38 Chinese firms realized IPO in American stock markets with fundraising of $4.557 billion. Thirty of them involved 72 PEs, whose returns in book value were about 7.48 times. Many PE funds received very high returns. For example, IDG Capital received a return of 107.21 times (Table 4.6).

Table 4.6

The top ten PE returns for exit through IPO in American stock markets from September 2010 to May 2011

| PE | Exit company | Return (x) |

| IDG Capital | SouFun Holdings Limited (NYSE: SFUN) | 107.21 |

| Sequoia Capital | Noah Holdings Limited (NYSE: NOAH) | 35.31 |

| Tiger Fund | Dangdang Inc. (NYSE: DANG) | 20.82 |

| Authosis Ventures | Bitauto Holding Led. (NYSE: BITA) | 19.53 |

| CDH Fund | Qihoo 360 Technology Co. Ltd (NYSE: QIHU) | 18.34 |

| Matrix Partners China | Qihoo 360 Technology Co. Ltd (NYSE: QIHU) | 16.46 |

| Highland Capital Partners/Redpoint Ventures | Qihoo 360 Technology Co. Ltd (NYSE: QIHU) | 13.65 |

| Legend Capital | Bitauto Holding Led. (NYSE: BITA) | 12.27 |

| Chengwei Ventures | Youku Inc. (NYSE: YOKU) | 11.41 |

| SIG Asia Investments | POLYBONA | 10.41 |

Source: www.chinaventure.com.cn

Among Chinese IPOs on American stock markets, the PE capital invested in companies in the finance industry received the highest return, which was 35.1 times; followed by 13.55 times for PE capital investments in companies of the internet industry. The returns of PE investments in companies of the telecom and media industry were about seven times. The lowest return was from real estate, medical and health service industries, which was less than one (Table 4.7). For those 30 companies involved with PEs, it took 30.6 months on average from receiving the first round of PE investment to realize IPO. Mining and mineral industries took the shortest time, only 10.7 months; manufacturing and real estate took 20 months; and PE investments in the internet industry had the longest time, about 4 years (Table 4.8).

Table 4.7

The PE returns of different industries for IPO in American stock markets from September 2010 to May 2011

| Industries | Returns (x) |

| Finance | 35.1 |

| Internet | 13.5 |

| Telecom | 7.3 |

| Culture and media | 7.1 |

| Chain operation | 6.6 |

| Manufacturing | 5.8 |

| IT | 3.0 |

| Farming and forestry | 2.7 |

| Education | 2.2 |

| Real estate | 0.7 |

| Medical and health service | 0.7 |

| Mining and mineral | 0.6 |

| Average return | 7.5 |

Source: www.chinaventure.com.cn

Table 4.8

Average months needed for IPO by companies in different industries in American stock markets from September 2010 to May 2011

| Industries | Months for exit |

| Mining and mineral | 10.67 |

| Manufacturing | 19 |

| Real estate | 22 |

| Education | 28.5 |

| Chain operation | 35 |

| Farming, fishing and forestry | 35.6 |

| Medical and health service | 37 |

| Finance | 39 |

| Internet | 48.3 |

| Average months for exit | 30.6 |

Source: www.chinaventure.com.cn

Since 2012, exit through IPO in American markets has become more difficult than before, for three reasons. The first is the financial crisis, which is causing the American capital market to perform poorly. The second is the bursting of the China concept stock bubble caused by financial scandals among China concept companies and selling their stocks short by some hedging funds. The third is the negative influence of variable interest entities (VIE).

PEs’ exit through secondary markets

The global financial crisis and the worrying performance of China’s economy in 2011 caused PE fundraising and PE investments to drop sharply, and many defaults of investors on the committed investment. China’s PE market is starting to face a turning point of development. Some LPs and GPs have urgent requirements for asset liquidity and project exit, and are asking for development of a PE secondary market. In particular, some PE funds have become disillusioned with the asset class and are looking for a way out of their fund positions. Meanwhile, when being listed on the overseas market becomes difficult, it is also hard for PEs to maintain the high return on investment (ROI) within the fund existence period relying on IPO. They need diversified channels of exit to turn the profits on book into real profits. Therefore, the construction and development of the PE secondary market are becoming more important than before.

In China, state-owned capital took as much as about 50 percent of market shares of the PE market. To avoid moral hazard in the trading and realize rational pricing, a trading platform with market creditability and mature trading rules is needed to provide the trading services. On 28 June 2012, Beijing Financial Assets Exchange (CFAE) launched the PE Secondary Market Development Alliance and the PE Secondary Market Trading Platform, sponsored jointly with China Beijing Equity Exchange (CBEX), China Association of Private Equity (CAPE), and China Beijing Stock Registration & Custody Center (CBSRCC). The CFAE released the revised PE secondary market trading rule system on the same day. The alliance is to facilitate the trading of LP interests in RMB funds, to offer a fair and standard service platform for GPs and LPs that have the need to exit, and to promote secondary trading. It is expected that 1000 secondary deals worth a collective RMB 30 billion ($4.7 billion) will be made by 2015.

However, whether the platform can guarantee transactions with transparent information is argued. An open platform will theoretically help LPs to exit. But, in reality, it is very difficult to operate, because LPs usually need to get consent from GPs before selling anything and both parties prefer to reach settlements in a private manner. From the perspective of GPs, they have to think about how their reputation may be negatively affected by selling the assets they manage. Meanwhile, GPs who are going out of business and have poor-quality portfolios are not incentivized to advertise the fact that their LP interests are being sold or facilitate any transactions. Furthermore, there is often insufficient knowledge regarding the quality and valuation portfolios for investors to know what they are buying. To develop the secondary market well, experienced and professional intermediaries for valuation and rating are essential. Basically, Chinese firms don’t have the skill set and experience required to evaluate secondaries properly, while foreign-sponsored funds are not allowed to participate due to regulatory restrictions. In China, the most natural buyers of RMB secondaries will be Chinese insurance companies and the scattering of established institutional LPs, such as the National Social Security Fund.

PE performance

Before China’s launch of GEM in 2009, China PE’s major exit path was by IPO on overseas stock exchanges, mainly in American stock markets. So, the return of Chinese PEs was related to American stock markets and American economic performance. The return was not as high as exit in China. Before the American financial crisis in 2007, Chinese PEs’ internal rate of return (IRR) tended to be increased year by year (Table 4.9). Since China launched GEM, this has become the main exit path for Chinese PE investments. This means that a PE’s performance is related to Chinese investment banks, because they can help the PE investment to realize IPO on GEM with high P/E ratio. In 2011, when a PE did its investment and purchased some equities from its target firms, it was quite normal to pay 15 or 16 P/E for the equity purchase.

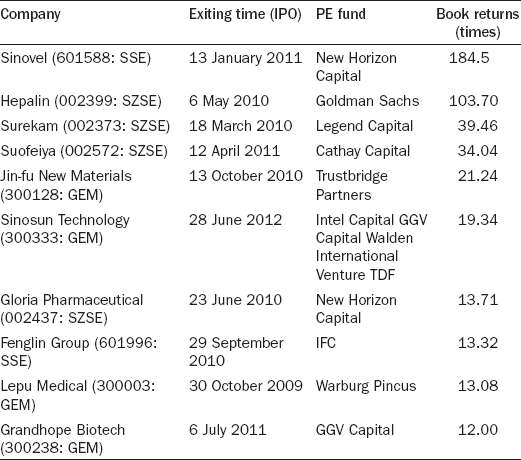

In 2011, when Sinovel Wind Group (601558:SSE), the first producer and seller of wind turbines in China, was listed on China’s main board, New Horizon, a Chinese local PE, exited with 184.5 times book return for its investment in Sinovel. This has been the highest book return, but it has not been unusual to see Chinese PEs make more than ten times returns (Table 4.10). The highest book return for a foreign PE exiting through IPO in China was achieved by Goldman Sachs for 103.80 times in its investment in Hepalink.

Table 4.10

The top ten book returns for PEs exiting through IPO in China’s main board since 2009

Source: SSE and SZSE

The high returns of China PE investments mainly result from two reasons: good beta and alpha. Alpha helps a PE to be a deal, while beta makes a PE investment capitalized by the right way of exit, which, in most cases, is IPO. Chinese market beta, particularly high P/E ratio, greatly shapes PE returns. Meanwhile, PE investment returns will be shaped more by alpha; that is, the actions taken by GPs themselves. But, in 2012, negative forecasting of China’s economy makes the valuation lower, normally under ten times. Lowering valuation has been a trend. In addition, since April 2012, CSRC has asked that the P/E ratio of an IPO should not be higher than 25 percent of the industry average P/E ratio. That does affect the return and performance of a PE investment. The year 2012 has seen a significant decrease in the average book return for PE investment exiting via IPO. In the first quarter, the average book return for PE investment exiting through SMEB and GEM was only 3.79 and 2.91 times respectively, compared with 4.88 and 6.53 times in the same quarter in the previous year.

RMB-denominated PE funds

The foreign PE investors are facing intense competition from an increasing number of Chinese PE funds raising Yuan competing for many of the same deals. According to McMahon (2012), in 2010 PE funds in China raised $16.9 billion in dollar funds, compared with $10.7 billion in Yuan funds, while in 2011 Yuan funds topped dollar funds by $23.4 billion to $15.4 billion. Western PE firms are keen to raise new capital from China. Yuan-denominated funds, recently made available to non-Chinese firms, face less red tape and enable PE outfits to team up with local governments to raise money and help locate deals.

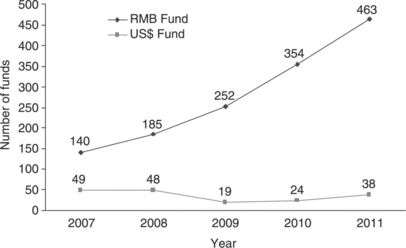

Since 2009, RMB funds tend to dominate China PE industry. In that year, RMB funds were more than foreign currency funds in both fund quantity and fund size in total (Figure 4.6 and Figure 4.7). In 2011, 463 RMB PEs were set up, and the total size was about RMB 220.5 billion Yuan or US$ 34.77 billion, while US$ funds were only 38 with fundraising of US$4.37 billion.

Figure 4.7 The fund size in RMB and US$ in different years (US$ billion) Source: CVSource (http://www.chinaventuregroup.com.cn/database/cvsource.shtml)

For a long time, overseas PE firms have struggled to make inroads into China due to China’s foreign exchange control. Since 2010, overseas investors have been allowed to set up Yuan-denominated PE funds by limited partnership in some cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. Foreign investors can obtain the qualification of Qualified Foreign Limited Partner (QFLP), which allows them to change their foreign currencies to RMB for establishing RMB PE funds. Beijing and Shanghai have been given quotas of up to $3 billon each to allow PE firms to bypass the country’s strict currency control and put offshore money into their new RMB-denominated funds. By 2011, 14 foreign PEs had received the QFLP qualification in Shanghai. Some famous global PE firms, such as Foson Carlyle, Hony Capital and Blackstone, have obtained the qualification. They often team up with local governments for fundraising and help locate deals. In May 2012, Goldman signed a deal with the Beijing government to launch a Yuan-denominated fund that aims to raise RMB 5 billion Yuan ($770 million). Blackstone closed its first round of fundraising for its RMB PE fund in early 2011. Morgan Stanley launched its first Yuan-denominated PE fund in China in May 2011.

Since 2010, Western PE firms have been allowed to raise capital and set up Yuan-denominated funds on the mainland. The funds often team up with local governments to raise money and help locate deals. Foreign investors had always hoped that their RMB PE funds would be treated as local and receive national treatment, when most of the fund, about 95 percent, was raised in China. However, the NDRC, the country’s economic planner, has ruled that Yuan-denominated PE funds can only be treated as local if all of their capital is raised within China; otherwise the funds will be treated as foreign. Further, in May 2012, the NDRC ruled that if the GPs of a PE are foreigners, no matter how much capital is raised from domestic sources, the PE will be treated as a foreign fund and cannot obtain national treatment. This means that foreign PE funds in China are like foreign direct investment (FDI) there and have to follow the restrictions put on foreign investment in China. Their investment should follow the Catalogue of Industries for Guiding Foreign Investment published by the MOFCOM. For example, foreign funds aren’t allowed to invest in some sensitive industries, like defense-related companies, and face restrictions investing in internet, telecommunications, and education sectors. In addition, foreign managers raising funds in China need to bring in their own money to the fund from overseas, usually between 1 percent and 5 percent of the fund’s total value.

In the coming months the government is set to hand the cities of Beijing and Shanghai quotas of up to $3 billion each to allow PE firms to bypass the country’s strict currency and investment controls and put offshore money into their new RMB-denominated PE funds.

China Sovereign Wealth Fund

On 29 September 2007, China established its sovereign wealth fund, China Investment Corporation (CIC), whose initial capital was $200 billion. CIC has been one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world. The main purpose of creation of the CIC was because China had the largest foreign exchange reserves, which reached $1.53 trillion in 2007 and more than $3.18 trillion in 2011. Although China had the largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, its management of the capital was poor. It even invested 21 percent of the total reserves to purchase bonds of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and once held bonds of $376.3 billion. The loss was disclosed. But the Chinese public believed that the loss could be huge. That might be a reason for establishing CIC. Just as CIC said, it was a vehicle to diversify China’s foreign exchange holdings and to achieve higher long-term returns within acceptable risk tolerance on its investments. CIC also has another purpose, which is to maintain the stability of China’s financial market with its huge capital. The CIC has two major arms for its investments: Central Huijin Investment Company (CHIC) and CIC Investment Corporation International Co., Ltd. (CIC International). CHIC mainly provides capital for domestic financial firms, particularly through its wholly owned subsidiary, China Jianyin Investment Company, to manage domestic assets and the disposal of non-performing loans. CIC International mainly manages overseas investments. It was established on 28 September 2011, and received a $30 billion injection from CIC in December 2011. CIC has made some significant investments (Table 4.11).

Table 4.11

CIC main investments since 2007

| Time | Investment |

| December 2007 | Invested $5.6 billion to buy 10% stakes of Morgan Stanley |

| July 2009 | Invested $1.5 billion in Teck resources |

| March 2010 | Invested $1.6 billion in AES |

| December 2011 | Invested $3.15 billion in GDF Suez Exploration & Production International SA |

| December 2011 | Invested $850 million in Atlantic LNG Company of Trinidad and Tobago |

Source: CIC

In the global market, CIC has made some strategic achievements. For example, on 28 December 2011, CIC acquired a 25.8 percent shareholding in Shanduka Group, an investment holding company in South Africa with businesses covering mining, finance and consumer goods, for $247 million, marking its foray into Africa. In 2011, CIC set up the Russia-China Investment Fund with Vnesheconombank (VEB), Russia’s state development bank, and the Russia Direct Investment Fund (RDIF). CIC also launched the China Belgium Mirror Fund with Belgian Federal Holding and Investment Company (SFPI) and “A” Capital. Meanwhile, some of its investments caused argument. On 20 May 2007, China Jianyin Investment Company purchased 9.9 percent stakes of Blackstone Group in non-voting shares worth $3 billion. The investment was debated and criticized due to the poor performance of return. Its overseas investments are mainly in the North American and Asian Pacific regions. In addition, CHIC was actively involved in restructuring and investment in China’s largest state-owned banks, and became a major shareholder (Table 4.12).

Table 4.12

CHIC’s investment in China’s large banks (by 31 December 2011)

| Banks | Share of ownership |

| Bank of China | 67.6% |

| China Construction Bank | 57.1% |

| China Development Bank | 47.6% |

| Agricultural Bank of China | 40.1% |

| Industrial and Commercial Bank of China | 35.4% |

Source: CIC

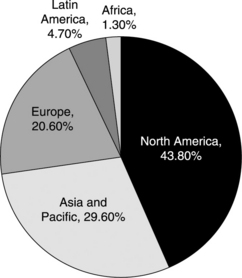

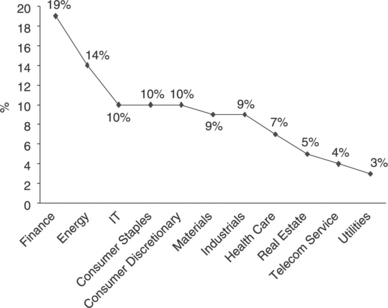

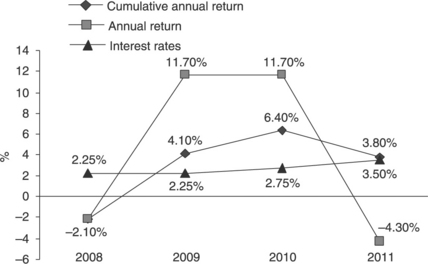

To reduce risk, CIC takes a diversified investment strategy. Its investments are diversified both in geographic regions, involving five continents, and in different sectors, involving 11 industries. But it prefers North America and Asia, which account for more than 70 percent of its total investments; while Africa only accounts for 1.3 percent (Figure 4.8). CIC prefers investing in the financial industry and the energy industry, while it ignores the public utilities sector (Figure 4.9). Since CIC’s establishment, its investment performance has always been subject to debate (Figure 4.10).

For the four years from 2008 to 2011, its cumulative annual returns did not outperform the interest rates of the same period. CIC’s senior management team is mainly from central government rather than professionals with international investment experience. Their background and experience are advantageous for understanding and identifying China’s opportunities, while they may not be competitive for global investment. CIC is facing a serious challenge to manage its investments in the current financial crisis.

Taxation issue in China’s PE industry

In China, if a PE is structured by corporation, its LPs should pay 5 percent business tax, 25 percent of corporate income tax and 20 percent of individual income tax. For a PE structured by limited partnership, the current tax laws and regulations only provide limited consistent guidance on the tax treatment of partnerships and partners. Normally, corporate income tax is not paid, while 5 percent business tax is liable to be paid. Besides, each LP should pay his individual income tax. It is said that the central government is planning to impose a 35 percent to 40 percent capital gains tax on PE investment in the near future. Perhaps because of the prospect of tax benefits, limited partnership may become the main type of structure in China.

Since PE has emerged in China, many local governments want to attract PE investments and encourage local PE development. They have created some favorable policies involving lower tax treatment. For example, some local governments provide low tax on PEs, down to 20 percent or even only 12 percent of the total. However, most of these treatments appear contradictory to the existing tax laws and regulations in relation to the taxation of partnerships. The central government may clean up the local tax treatment. A new regulation on tax treatment of partnerships and partners is in draft and will take effect in the next few years. Favorable tax rates are very attractive to PE funds. Mainly due to preferential tax, 2396 PE management companies had registered in Tianjin City by 2011. The total registered capital reached RMB 441 billion Yuan, which accounted for about two-thirds of the total PE management companies in China.

Policies to manage the PE industry

In developing the PE industry, some problems, such as chaotic inter-authority coordination and regulation, emerged. After some illegal fundraising cases had emerged in several regions, the NDRC decided to regulate PE funds. A filing system was then developed in 2010. On 14 February 2010, the NDRC officially issued the Circular on Further Regulating the Development and Record Filing of Equity Investment Enterprises in Pilot Areas, which asked for compulsory record filing, intending to regulate PE in all its aspects, including accredited investors, fundraising forms and information disclosure.

On 31 January 2011, the NDRC issued the Circular on Further Regulating the Development and the Administration on Filings of Equity Investment Enterprises in Pilot Regions. It required the PE funds established in six pilot areas (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province and Hubei Province) and with a capital amount of RMB 500 million ($79 million) or above to file with the NDRC. The NDRC requires qualified equity investment enterprises (EIE) and some Equity Investment Management Enterprises (EIME) in the six pilot regions to file with the NDRC or a locally designated authority. Eleven guidelines to guide the filing were issued on 21 March 2011.Under the Circular, an EIE established in one of the pilot regions must file with the NDRC if its committed capital exceeds RMB 500 million (or an equivalent amount in foreign exchange), unless (i) the enterprise has been filed under the venture capital regulation, or (ii) all its capital is contributed by one institutional or individual investor, or by two or more investors that are wholly owned subsidiaries of one institutional investor. The Guidelines further exempt funds whose committed capital is above RMB 500 million, but which have less than RMB 100 million actually paid up from the filing requirement. The NDRC in the Guidelines recommends that each investor to an EIE commit capital of no less than RMB 10 million to reflect the requirement in the Circular that the EIE investors must be of sufficient ability to understand and bear the risks related to their investment. Moreover, the Guidelines expressly prohibit any investor from investing in an EIE through a nominee structure. The Guidelines also emphasize that a SOE, listed company, or social service organization for public benefit must not be a GP of either an EIE or an EIME.

To address illegal fundraising activities and irregular operations of PE funds, the NDRC issued the Circular on Promoting the Standardized Development of Equity Investment Enterprises on 8 December 2011. It mandates nationwide filing for all PE funds, regardless of the establishment jurisdiction or the capital size. Meanwhile, it confirms that EIEs may be formed as a limited liability company, a joint stock company, or a partnership in China. This conforms to the current common practice of domestic PE funds, all of which are formed as either limited liability companies or domestic partnerships (most of which are limited partnerships). However, it should be noted that, under the Regulation on the Administration of Foreign-Invested Venture Capital Enterprises, a FIVCE (Foreign-Invested Venture Capital Enterprise) can be formed as a wholly foreign-owned enterprise, an equity joint venture, a contractual joint venture as a legal person, a contractual joint venture as a non-legal person, or a foreign-invested partnership. It is not very clear whether a non-legal person joint venture may still be available to a FIVCE under the New Circular.

How to make a successful PE in China?

To be a successful PE in China, the most important thing is to understand China’s environment. Just as John King Fairbank (1983) describes in his book United States and China, for businessmen, the tradition in China had been not to build a better mousetrap but to get the official mouse monopoly. Because China’s economy is a regulatory economy, and the government controls many resources, businesspeople often make obtaining the resources or supports from government their priority rather than producing best-quality products. In China’s PE industry, how to obtain the right to become involved in a pre-IPO list project or obtain high PE alpha is an example. Meanwhile, the government makes policies to regulate the economy and industries, including supervising the PE industry, which can greatly affect PE performance, either directly or indirectly. To be successful, a PE needs to understand not only the economy but also, sometimes, politics. To be a successful PE in China, understanding and adapting to Chinese conditions and environment is critical. The emerging PE sector is developing its own ecological system involving different interest groups such as local governments, banks, investment banks, entrepreneurs, and industrials. In the ecological system, developing good relations with them and making the right trade-offs between them are a kind of art and wisdom.

In operational aspects, to be successful, China’s PE firms need to identify investment opportunities arising from China’s economic development and growth, and deepen and strengthen their portfolio management capabilities. As the largest emerging and transitional economy, each new economic policy and economic change in China’s economy could bring huge investment opportunities. For example, China’s launch of GEM directly contributes to the taking off of China’s PE industry. It opens up a main exit market to China’s PEs, and brings PE fund returns to an extremely high level. As an emerging economy, China is full of opportunities. China’s upgrading of its traditional industries and encouraging high-tech and new energy industries provide great investment opportunities for PEs. For example, New Horizon Capital took one of these opportunities by investing in Sinovel, and received 184.5 times book returns. With more and more Chinese firms going global, there are opportunities for PEs. Both Chinese and foreign PEs can help Chinese firms’ global investments. PEs may seek opportunities to help Chinese firms’ internationalization, particularly in cross-border acquisitions. For example, in January 2012, CITIC PE helped Sany Heavy Industries, a Chinese construction machinery manufacturer, to acquire 100 percent of shares of the famous German manufacturer Putzmeister from the “Karl Schlecht foundation.” The deal was 360 million and CITIC PE invested in 36 million or purchased 10 percent equities of Putzmeister. There are a lot of similar cases in China.

To be successful, a PE needs global vision and to understand the global economy and industries well so that it can help operating companies to create value. Many PEs provide a value-adding service, such as a hunter helping firms to look for “O class” senior managers, including chief financial officer (CFO) or chief operation officer (COO), and develop a professional management team. In the near future, PEs may also help those operating companies in which they are involved to carry out restructuring or integration in global markets. A successful PE in China is one with Chinese characteristics and global vision.

Challenges in developing PE in China

The biggest challenge facing PEs in China may be the uncertain environment they operate in, such as the lack of clear and transparent procedures and requirements in many fields. For example, Vats Liquor Store (Vats Liquor Chain Store Management Joint Stock Co., Ltd), whose purpose is “Innovating in marketing, operating and managing model of liquors, focusing on authentic liquor store management and developing China’s No. 1 trusted authentic liquor store brand” and whose main business is representing and distributing China and world famous liquors, was rejected by CSRC for its IPO. Three famous PEs invested in Vats Liquor Store: KKR, New Horizon Capital and CITIC PE. CITIC PE is an arm of CITIC, one of the best Chinese investment banks, and is the strategic onshore PE platform of CITIC Group and CITIC Securities. So, CITIC PE understands IPO qualification and procedure well. The three PE funds were confident of the success of Vats Liquor Store’s IPO according to their understanding and analysis. However, the IPO application was rejected with no explanations for the rejection. That is a good example of the uncertainty in developing PE in China.

Another example is the policy conflicts between local and central governments. Local governments provide favorable conditions to encourage PE development to locate in their regions; while those favorable policies, such as low tax rates, are against the central government’s policy. The challenge is not in the policy itself, but in the way governments regulate the PE industry. The government has become used to regulating industries rather than developing a market-driven way for a fair and transparent business environment. How to adapt to the uncertainty and grow up in the environment can be a big challenge for PE development in China. Another challenge is in talents. Developing China’s PE industry requires a large number of financial professionals who understand both global and Chinese trends and markets. In China, there is a great lack of qualified PE professionals. It is often said that, in the PE industry, it is much easier to find enough capital than qualified PE management professionals. Meanwhile, many PE funds are short-sighted and only want to make quick money. It is time for both GPs and LPs to reexamine their enduring strategies and long-held beliefs about PE as an asset class and how to play to win.

The future of private equity in China

PE industry is only at its infant stage in China, and has great potential for further development. According to Mr John Zhao, the CEO of Hony Capital, in America, PE investment is about 1.4 percent of American GDP; in India, it is 1.8 percent. However, in China, it is as low as 1.2 percent. As the second-largest economy in the world, China’s economic growth and development will provide PE with a bright prospect. In the near future, at least two factors may drive China’s PE to keep thriving. First, the limited investment opportunities available in China mean that rich Chinese people, whose population is growing with China’s economic growth, are looking for investment opportunities both internationally and domestically, and PE can be a good choice. Second, the Chinese government encourages the development of the PE industry and is exploring how to improve the contribution of private capital to economic growth. Chinese PE investments can touch all sectors of the economy, from industrial goods and retail to financial services and technology, as long as the project invested can be listed in China’s GEM, which can contribute economic growth in the long run. To seek sustainable economic growth, the government would like to support the developing PE industry.

Unlike Western PE funds, which have three major routes to exit – strategic sales to corporate acquirers, IPOs and sponsor-to-sponsor transactions – Chinese PE funds prefer and mainly take IPOs. This has been the major route to exit. Only IPO has proved to be a consistently attractive option with extremely high return. In future, other exit routes such as secondary markets may be developed. Value creation may be the main stream in China’s PE industry. Since 2012, it is widely believed that Chinese PE’s “golden age” of mega-deal making and incredible returns is near its end. Restructuring within the PE industry is going on. Acquiring assets from other PE funds in secondary buyouts may be prevalent in the near future. A winter of the industry is coming. But, after winter, there will be another spring.

Summary

China’s PE fund industry has been dominated by both foreign and local PEs. At the beginning, foreign PE funds pioneered the sector, while they now share the sector with Chinese local PE funds. The launch of GEM provides China’s PE funds with a great opportunity for growth, and brings to PE funds a great exit strategy with considerable returns in several years. There is a policy conflict between central government and local governments in managing PE fund development. After the boom times, China’s PE funds are entering a period of adjustment.