2

It Could Get Better— or $3 Trillion Worse

Six years ago nobody accessed e-mail via a tablet. Nobody talked about “big data.” Companies didn’t have private cloud programs. Most people assumed that security technology companies such as RSA could not be breached. Almost nobody had heard of Anonymous or LulzSec, and didn’t think that jihad might be carried out by cyber-fighters. Edward Snowden was an anonymous contractor working on computer security for the CIA. And national newspapers didn’t carry front-page stories about governments lobbing charges and countercharges against each other about the use of cyber-espionage.

The cybersecurity context that companies operate in today is extraordinarily dynamic. The digitization of business processes continues to accelerate, a dizzying array of new technologies is available in the marketplace, and new security products emerge to acclaim but sometimes turn out to be less effective than promised. Attackers proliferate, experiment with new techniques, and become more audacious, while hundreds of government agencies in dozens of jurisdictions shift policies, roll out regulations, and invest in all manner of defensive and offensive cybersecurity capabilities.

Amid this confusing cacophony of activity, companies and other institutions must make decisions that will affect them 5 and even 10 years in the future. They must invest in research and development (R&D) projects so that they can reap benefits later. Technology they implement and applications they develop now will support business processes far beyond. Outsourcing arrangements contracted now will last at least 5 or 6 years, and those frontline technology experts brought on board today need to be able to grapple with problems we have not even though of yet, just as their predecessors are coming to terms with the challenges of today.

The situation is no better for other participants in the cybersecurity ecosystem. Vendors must invest now for the products of 2020 and beyond. Likewise, governments will write legislation that will stay on the books for years or even decades. So how are executives supposed to take the cybersecurity environment into account when making strategic decisions, when it’s hard to predict almost anything about how that environment will evolve?

Scenario analysis is one of the most effective techniques for thinking about the implications of highly confusing, dynamic environments such as cybersecurity. Royal Dutch/Shell developed modern scenario planning in the late 1960s. By examining uncertainties, Shell’s Group Planning organization, led by Pierre Wack and then Peter Schwartz, first developed scenarios that envisioned the possibility of spiraling oil prices in the 1970s1 and then their collapse in the 1980s. This enabled Shell to prepare for market conditions it would not previously have considered.2

As described in Peter Schwartz’s book The Art of the Long View, scenario analysis involves creating stories about alternative worlds.3 These worlds are plausible futures based on a prioritized set of the drivers that could create each future, for example, the technologies that might be developed or how consumer preferences might change.

It is important that the worlds feel real and can be described in detail. What do they look and feel like? Who wins and who loses? What are early indicators that each world might be coming to pass? Business and public policy leaders can then look across all the potential worlds to see how they might steer a course toward the most favorable outcome. For example, are there actions that could increase the chance of a more attractive world coming to pass, and are there early warning signs to look out for that would indicate that managers should adjust their plans as one world or another comes into reality?4

SCENARIO PLANNING AND CYBERSECURITY

We are not the first to apply scenario planning to cybersecurity. For example, Jason Healey of the Atlantic Council’s Cyber-statecraft initiative laid out a range of scenarios including Status Quo, Conflict Domain, Balkanization, Paradise, and Cybergeddon in “The Five Futures of Cyber Conflict.”5

Compared to previous efforts, we focused less on geopolitics and much more on how different cybersecurity scenarios could affect the global economy’s ability to derive value from technology innovation. This means looking at issues of commercial, regulatory, and consumer behavior as well as the implications for individual institutions that need to protect themselves. In developing our scenarios, we drew on our interviews to identify more than 20 drivers of the future cybersecurity landscape. They included everything from expansion of the “surface area” of corporate networks to the ability of governments to enforce cyber-crime laws.

Twenty drivers is too unwieldy to be practical for scenario planning, so we prioritized the eight that will have the greatest impact and grouped them into two categories, which became macro-drivers:

Intensity of Threat

- Ease of use of attack technologies

- Level of disaffection among technologically sophisticated young people

- Proliferation of attack tools

- Sophistication of attackers and attack tools

Quality of Response

- Sophistication of institutions in defending themselves

- Pace of defense technology innovation

- International cooperation in fighting cyber-crime

- Quality of information/knowledge sharing across public and private sectors

Playing out the possible trajectories of each of these macro-drivers gave us three possible scenarios: muddling into the future, digital backlash, and digital resilience (Figure 2.1).

- Muddling into the future. In this scenario the intensity of threat and the quality of response proceed roughly at the same pace. This world has many similarities to the one we live in today. Attackers continue to harass important institutions who, in turn, feel they are engaged in a never-ending game of “whack-a-mole.” Cybersecurity is challenging, expensive, and a pain in the neck for most institutions, but, for the most part, cyber-attacks have only a limited impact on the world economy’s ability to derive value from technology innovation.

- Digital backlash. In this scenario, the intensity of the threat outpaces the quality of institutions and governments to defend against cyber-attacks. There is a series of not only embarrassing but also highly destructive attacks that diminish confidence in the digital economy. As a result, regulators, institutions, and even consumers apply the brakes to digitization, resulting in dramatically reduced value from technology innovation.

- Digital resilience. In this scenario, institutions and governments rally to build resilience against cyber-attacks. Attacks and breaches continue to occur, but it becomes clear that their impact can be limited. Targeted and flexible defense mechanisms reduce the loss associated with protection against cyber-attack. As a result, the adoption of important technologies accelerates noticeably.

FIGURE 2.1 The Change in Intensity of Threat and Quality of Response Leads to Different Scenarios

Pessimists might ask why there’s no scenario that describes societal or economic collapse of the type that Hollywood might portray—indeed has done in low-budget films such as Dragon Day, where a cyber-attack destroys American society. In this case, mayhem is triggered by the simultaneous activation of a virus that is installed on every “Made in China” microchip.

The fact is that there is no “kill switch” for the online economy. Planning and executing a series of cyber-attacks sophisticated, wide-ranging, and sustained enough to bring a large, modern, diversified economy to its knees requires the resources of a powerful state. If two superpowers wanted to destroy each other’s economies using cyber-weapons, they probably could. However, as Thomas Rid points out in Cyber War Will Not Take Place, they could also have destroyed each other at almost any time in the past using other weapons at their disposal.6

Cyber-destruction requires actors who have tremendous technological sophistication, available resources, and—most important of all—sufficient motivation. As we write, no state or other actor ticks all three boxes. The interconnectedness of the global economy means that a country that disrupts, for example, a foreign bank’s trading operations, may well find that its own economy suffers as a result. The motivation for cyber-destruction is not there when you look beyond film scripts.

What’s at Stake?

After identifying and describing the scenarios, we quantified their impact in terms of the world economy’s ability to derive value from technology innovation.

McKinsey’s independent research body, McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), has been analyzing the value of technological innovations. In its “Disruptive Technologies” report, it focused on 12 technologies that society is counting on to transform life, business, and the global economy with an aggregate annual global economic impact of $14 trillion to 33 trillion by 2025.7

However, our interviews with cybersecurity leaders and experts made clear that exploiting many of these technologies successfully hinges on wide-ranging confidence in the confidentiality and integrity of the data on which they depend. It is much harder to convince doctors and patients to accept the use of electronic health records if they believe those records might be stolen or compromised. Many sessions at the World Economic Forum’s 2014 annual meeting in Davos echoed this concern with conversations about technology innovations quickly evolving into discussions about whether it would be possible to secure the relevant data.

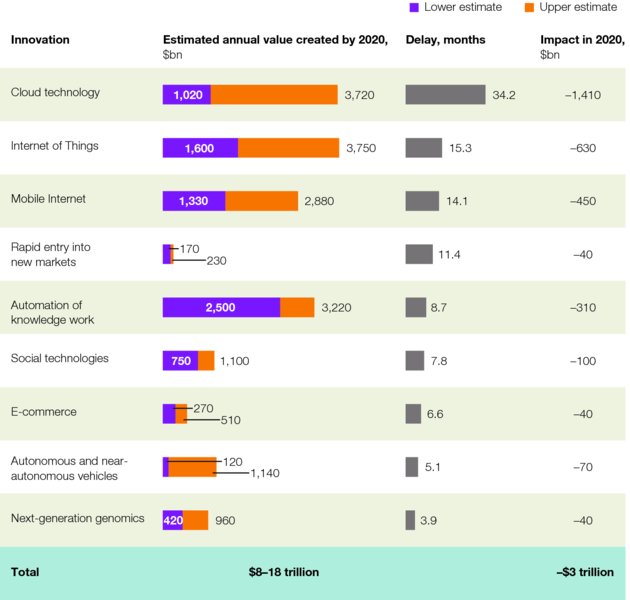

We argue that 9 of the MGI’s 12 technological changes are at meaningful risk of being affected by cybersecurity threats: cloud computing, the Internet of Things, the mobile Internet, rapid entry into new markets, automation of knowledge work, social technologies, e-commerce, autonomous vehicles, and next-generation genomics. Rather than look as far out as 2025, we interpolated the MGI data to determine that in aggregate these 9 could deliver annual value of $8 trillion to 18 trillion between 2013 and 2020, assuming all are implemented aggressively (Figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2 Nine Technologies Could Create $8 Trillion to $18 Trillion in Value by 2020

Sources: MGI reports, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), International Monetary Fund (IMF), McKinsey Economic Analytics Platform, industry leader interviews

However, technology executives told us that their company’s ability to roll out these capabilities would be heavily affected by its overall position regarding cybersecurity risk. Under the digital resilience scenario, the full $18 trillion could be realized annually, but delays in implementation that would occur under the other two scenarios would have a meaningful impact on that. For example, the adoption of cloud computing could generate up to $2.7 trillion in annual value by 2020—but only under the digital resilience scenario. In the muddling into the future scenario, there would be a delay of slightly more than 11 months in adoption. This would equate to a $470 billion impact on potential value in 2020. In the digital backlash scenario, the delay to the adoption of all the technologies would be three times worse, so, for the cloud computing example, the delay would be just shy of three years and the economic impact would also be three times as worse: in 2020, $1.4 trillion of lost value in the global economy.

Naturally, these numbers are estimates with margins for error but whatever the precise numbers, the impact is meaningful. If we delve deeper into the three scenarios, we can see what will bring them to pass, what the world would look like in those circumstances, and what their impact will be on realizing the full value of these game-changing technologies. CIOs and other business leaders who already find today’s cybersecurity environment challenging may realize that it could get a lot worse.

SCENARIO 1: MUDDLING INTO THE FUTURE

January 15, 2020

It started out just another cruddy day at the office for Jane Schnauggs, chief information officer (CIO) at HyperCare, one of the United States’ largest publicly traded hospital networks.

She was frustrated and exhausted from this year’s budget process. Her so-called partners in the business expected her to deliver the most recent generation of mobile patient experience and clinical decision support tools, without any increase in the IT budget.

It had taken Jane nearly 18 months to find Frank, but she hadn’t realized how expensive and controversial her new CISO would turn out to be. The new tools for detecting malware weren’t that expensive, though nobody could show her how they could be made to work together in any reasonable time frame yet. The real budgetary problems were the network and application rearchitectures that Frank insisted were essential. “They just were never designed to be secure.” That they didn’t show up in the security budget didn’t make them any less expensive. What’s more, lots of monitoring and patching activity—much of it mandated by the regulator—was eating up many of the hard-won operational efficiencies she had achieved over the past few years. It was only January, and she already feared that she was at risk for this year’s budget and the Q4 meeting with the chief financial officer (CFO) would be unpleasant in the extreme.

Even worse, both the mobile and clinical support projects were now months behind schedule because Frank had been able to demonstrate that there were fundamental flaws in the way each application handled sensitive data. And every couple of days she got another e-mail from another senior doctor telling her what a pain in the neck the new password policies were.

Her office door opened, interrupting Jane’s silent griping.

“Frank,” she said, “Please don’t take this the wrong way, but you’re not the person I most like to see dropping by my office unexpectedly.” Frank gave that apologetic half-smile that typically preceded bad news.

It could have been worse. It could have been a lot worse. Fortunately, these attackers were relatively unsophisticated. They had managed to steal data on roughly 1,500 patients from the electronic health records system.

“If they hadn’t been controlling the malware from an IP address range that’s pretty well known for cyber-crime,” Frank said, “we’d never have caught it this quickly. They were probably planning to use the records for medical fraud. Or resell them to somebody who would. Market price for personal health information is probably getting close to $1,000 per life these days.”

The fines would be a couple of million dollars. Probably another two or three million to head off any civil suits. And the medical head of one of their largest hospitals promising a reporter that none of his patients’ information had been breached made them all look like idiots.

For a company with $15 billion in annual revenues, it was expensive but definitely manageable. Of course, once Frank came back to her with the costs to actually fix the flaw in the system, Jane knew there was just no way she was going to hit her budget this year.

The realization of the muddling into the future scenario is as much a story of what doesn’t happen as what does.

Attackers would continue to improve their skills, but state-level capabilities would remain in the hands of a small number of countries, each of which would be heavily invested in preserving the existing economic order. Countries continue to snoop shamelessly for political/military intelligence and economic advantage, but cyber-weapons remain in their silos. Other cyber-attackers continue expanding their activities, stealing identities, and enabling fraud, but they remain parasitic rather than destructive, diverting only a tiny percentage of the unimaginable sums sloshing through the global online economy into their own pockets. After all, a bank or online retailer they put out of business one day is one they can’t steal from the next.

Institutions would continue to protect themselves, devoting more resources to and demanding tighter control from cybersecurity models that are already barely tenable in 2014. Protecting an institution from cyber-attacks continues to be “IT’s problem,” and even more specifically “the CISO’s problem.” Senior executives would continue to formulate business strategies and lay out business processes with no consideration of how the underlying data would be protected. Limited engagement from business leaders makes it hard to determine what data needs most protection, so the IT security team tries to protect everything equally, which drives up costs and user inconvenience. Security would continue to be layered on top of application development projects and infrastructure environments rather than being embedded in them, adding to the time and cost of rolling out new technology.

The broader ecosystem offers only limited help to institutions in this scenario. Cybersecurity policy remains disjointed, with little cooperation among states and barely any coordination between different agencies and regulatory authorities within each jurisdiction. Intelligence agencies struggle to find a way to share the massive amounts of cyber-intelligence with private institutions without creating privacy concerns or compromising sensitive sources and methods. CIOs and CISOs, meanwhile, continue to face a bewildering maze of regulations touching on privacy and security. Vendors still bring innovative security technologies to market, but few standards emerge and most products are one-off solutions that don’t fit into a broader security platform without lots of labor-intensive system integration.

The Billion-Dollar Implication

For CIOs in this scenario, cybersecurity will feel like stepping back to be a New York City cop in the 1950s or early 1960s. Crime, both petty and organized, never goes away but never truly takes hold or fundamentally threatens the city’s society or economy. Nevertheless, CIOs are going to feel that their organization is always a half-step behind the attackers, caught in an endless cycle of applying security patches and trialing the next new security product that promises to identify attacks slightly more quickly. Being compliant with a maze of regulations often diverts resources from more pressing security needs. And reconciling regulations across different countries makes it harder and harder to run anything resembling a global technology environment.

Cybersecurity would continue to be a moderately expensive inconvenience for organizations, and tension would linger between security, business, and broader technology teams over the pace of technology innovation. Most critical innovations would still be implemented in a reasonably timely fashion, but the pace of delivering mobile and public cloud technologies in particular would lag expectation due to the nervousness around mobile security amid the platform’s ubiquity, and the lack of transparency into many cloud service providers’ security models. If we look at the Internet of Things, for example, the predicted five-month delay in adoption would mean forgoing $210 billion in value in 2020 (about 5 percent of the total annual value lost in this scenario) as regulators and institutions work out how to connect consumer appliances and industrial machinery to the Internet safely. Nobody wants their investment in Internet-enabled home automation to be a mechanism for criminals to know when they’re out of town or what valuable goods they own.

The muddling into the future scenario would result in an aggregate loss of just over $1 trillion in value in 2020 due to the deferred adoption of innovation technologies, with most of the impact in cloud computing, the Internet of Things, the mobile Internet, and automation of knowledge work (Figure 2.3).

FIGURE 2.3 Muddling into the Future Scenario Puts $1 Trillion at Risk

Sources: MGI reports, UNCTAD, IMF, McKinsey Economic Analytics Platform, industry leader interviews

SCENARIO 2: DIGITAL BACKLASH

January 15, 2020

“Well, this is certainly isn’t just another cruddy day at the office,” thought Jane Schnauggs as she sat between HyperCare’s CEO and general counsel in the Senate hearing room. Of course, she had tried to push the task of testifying before the Senate’s Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee on Frank, her CISO. But her general counsel had politely but firmly told her that, given the severity of the issues at hand, the Senate committee members would expect to hear from the company’s senior-most technology executive.

The senator looked down at his notes, then up at Jane. “I’d like to understand HyperCare’s decision making with regard to the security of its Mobile Clinician Experience program—I believe you refer to it as MCE? HyperCare failed to protect itself from a series of attacks that exploited vulnerabilities in MCE to shut down operating rooms at hospitals in half a dozen large cities. Emergency procedures had to be diverted to a nearby, publicly managed hospital, causing significant disruption. I also understand only the refusal of trained nurses to follow the instructions from HyperCare’s clinical decision support tool, which had been compromised by attackers, saved dozens of patients from potentially harmful treatments. In particular, Miss Schnauggs, what was your personal role in the process? Is it true that you dismissed concerns about the MCE program raised by your own security team?”

Jane paused and tried to remember all the coaching she received from the corporate communications team.

It had not been a fun couple of years to be the CIO at HyperCare. At some point, any number of hackers with time on their hands and an axe to grind had decided that embarrassing health care companies would advance their cause. Some seemed to think that HyperCare was a crony capitalist because it participated in the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Others apparently felt that a private hospital chain would sacrifice patient health and safety for profits.

It had started with those distributed denial of service attacks that swamped HyperCare’s Internet-facing servers, preventing patients from scheduling appointments or checking lab results. That was mostly an inconvenience. The information that attackers started to release online was more embarrassing: memos and e-mails in which management discussed how to maximize Medicare reimbursements were bad enough; the personal health information of celebrities and politicians was much worse—especially given the fines incurred and doubts it created about the privacy of electronic health records.

Frank’s team was sure that cyber-criminals were using the political attacks to distract the security team while they got on with the lucrative work of removing information for the purpose of medical fraud.

Silently, Jane thought about her frustration with the various public bodies. Sometimes it felt like Frank and his team had to deal with an alphabet soup of agencies that represented an overlapping and sometimes contradictory array of regulatory, law enforcement, and national security agendas. Frank told her every request for actionable information got waved aside, either on privacy grounds or because of the need to protect the intelligence community’s “sources and methods” in monitoring cyber-attacks.

She had invested a lot in protecting HyperCare’s systems and data. She found the budget for every security technology Frank had said the regulators expected, and approved rigorous controls for just about every major IT process. Every phase in the application development process had to be signed off by the security team before the project could advance. This hadn’t endeared her to her business partners, who complained that it took forever to get anything done. Yet they were also the same executives who shouted the loudest about IT’s incompetence whenever there was a breach.

MCE was supposed to have been the game-changer—the program that would reinvigorate HyperCare’s ability to use IT to improve medical productivity by tying enriched medical records with clinical decision support on one mobile screen. Given all the attacks, there had been a lot of skepticism from the board about IT’s ability to do big things without putting the business at risk. She had put her own personal credibility on the line in getting support from the senior management team. Ultimately, she had gotten there. The CFO had already baked the operational benefits into next year’s budgets. The doctors raved about the user experience.

Frank had told her, “We’ve spent a lot of time on the security architecture, but, at the end of the day, they required us to push a lot of data to the device for performance reasons. The level of integration from the vendors of the device, the operating system, the container, and the application platform are not what we would have wanted from the vendor. Is it crackable? Anything’s crackable. You have to make a call.”

Finally, Jane started to speak, so she could try to explain why she had given the approval to move ahead with the project.

The path to the digital backlash scenario is one strewn with inadequate responses, and it is far from being the unrealistic outlier scenario. Art Coviello, vice-chairman at security company RSA and one of the most respected commentators on the security environment, said, “Everyone assumes that we’re naturally going to end up muddling into the future. I don’t think that’s right. Unless something changes, we’re going to end up in with a digital backlash.”

Attackers would take the lead and the threats would become more worrisome. Network attack specialists realize they can supplement relatively modest corporate or state incomes by reselling malware, scripts, or techniques they have developed to cyber-criminals. Angered by charge and countercharge about cyber-espionage, governments decide not to bother pursuing destructive attacks that originate from within their territory, as long as those attacks are directed outward.

Technologically sophisticated young people, believing that government and business institutions aren’t responsive to their needs and concerns, would decide they can best make their voices heard by hacktivism. Some may argue that if large institutions acted ethically, they would have nothing to fear in having their internal deliberations made public.

If this environment crashes against an economy mostly using traditional, compliance-oriented cybersecurity models, those traditional models would buckle. Most application and infrastructure architectures were never designed to be secure. Companies don’t know how to focus their security controls on the most important information assets and risks. They can’t perform the analysis to identify attacks in real time. They can’t respond effectively in the event of a breach. The result would be a series of very public, very destructive attacks on major institutions that would trigger multiple types of backlash.

Many CIOs and CISOs we spoke to said that regulatory overreach was of the biggest cybersecurity risks, that is, that regulatory agencies would seek to establish ever more mandates about what security controls must be put in place, how many organizational lines of defense are needed, and which data must be hosted internally. In Davos, participants raised the specter of a “cyber cold war” in which different countries would use cybersecurity as a pretext to create “splinternets” that had different standards to the global (although increasingly seen as U.S.-run) Internet.

Alongside the regulatory challenges, there could also be an institutional backlash. Security is often the bottleneck in introducing new technologies, and many CIOs and CISOs told us that that it could get tighter and tighter in a more threatening cybersecurity environment: the greater the risk of cyber-attack, the more conservative institutions would become about introducing new technology-enabled capabilities.

Finally, there would be the possibility of a consumer backlash. This may be the least likely but the most destructive reaction. For the most part, consumers have taken publicity about cyber-attacks and breaches in their stride. They still shop at Target and still use Sony’s online gaming network. But there are already inklings of concern. For example, CISOs at wealth management and brokerage firms told us that their companies’ financial advisers were starting to get asked some pointed questions from mass-affluent customers about the security of their financial data in the wake of recent attacks. A recent survey conducted by the Ponemon Institute confirms that consumers are increasingly aware and concerned about cyber-attacks, even if they are not prepared to do anything about it just yet.8

However, if enough data were compromised to wake the sleeping giant of consumer concerns, the impact would be profound. Companies would suddenly find it much harder to convince customers to use mobile payments, service their accounts online, and accept electronic health records, let alone embrace any of the more advanced developments that may come along in the meantime.

Jeopardizing Business Models … and Entire Companies

When we explained the digital backlash scenario to a number of executives at semiconductor companies, their eyes widened. “If this scenario happens,” one of them said, “then the Internet of Things doesn’t happen or doesn’t happen quickly.” They went on to explain that their revenue growth projections depended heavily on the volume of chips needed for all these Internet-enabled appliances.

Banking CISOs had a different reaction. They believed their banks were already starting to experience the digital backlash scenario, while their less regulated, nontraditional competitors were still muddling into the future, and the distinction created a competitive disadvantage for the banks.

For CIOs and CISOs, the digital backlash will feel like an endless battle against a particularly creative and persistent insurgency. There’s always another potential attack coming from another direction and it will seem impossible to seize the initiative from the attackers. On top of that, many of the restrictions they are forced to put in place to counteract the attacks cause at least as much if not more frustration for their users. For CEOs and other business leaders trying to create value in the digital economy, this scenario would feel like New York in the 1970s, when fear of crime discouraged tourism, depressed investment, and drove residents and businesses to the suburbs and beyond.

As a result, almost every aspect of the digital economy would develop more haltingly. Institutions would invest in the Internet of Things more slowly. Regulators would be more aggressive in limiting which data can be stored in the cloud. Consumers would be more reluctant to adopt mobile commerce.

In this scenario, the value derived from the Internet of Things would be $630 billion less than its full 2020 potential due to a 15-month delay in adoption. In aggregate, the digital backlash would result in a staggering $3 trillion dollars in lost value in 2020 (Figure 2.4).

FIGURE 2.4 Digital Backlash Scenario Puts More than $3 Trillion at Risk

Sources: MGI reports, UNCTAD, IMF, McKinsey Economic Analytics Platform, industry leader interviews

SCENARIO 3: DIGITAL RESILIENCE

January 15, 2020

It had been a long day at the office for Jane Schnauggs, but it had gone a lot better than it might have.

“We definitely had some data stolen,” said her CISO Frank, “but it was mostly general business and operational data. I’m not entirely sure what they’ll do with the construction timelines for the new hospital build, but we can’t find any evidence that they were able to penetrate beyond our low-security zone. So we have no reason to believe than any personal health information has been affected. It’s good that we caught this early.”

It never failed to surprise Jane what data attackers would try to take. One country had undertaken a campaign to steal HyperCare’s medical practices for treating a range of acute and chronic diseases. The chief medical officer’s reaction had been priceless: “Do they know we publish this stuff in medical journals? I know the subscription fees for these journals are on the high side, but this feels extreme!” He also suggested inserting some sort of message into the network telling the hackers that HyperCare would be delighted to host a medical delegation from that country in any of its major hospitals. “Assuming appropriate credentials,” he noted dryly, “they would even be welcome to scrub in.”

Implementing software-defined networking had been a real battle. Many people in network operations had been highly resistant at first, and getting the initial investment had been excruciating, but it really paid off today. It allowed Jane’s team to set up separate zones for more sensitive workloads and data without the operational overhead of old-fashioned network segments. On days like today, it really slowed down attackers’ movement toward the most sensitive assets.

Of course, it had been a fight to bring business and medical leaders to the table to talk about cybersecurity. If the CEO hadn’t personally chaired that steering committee, it never would have happened. As it turned out, everyone knew personal health information was extremely sensitive and anything related to Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement was very sensitive. But the entire management team had been surprised at how much of their data wasn’t actually that confidential: building plans, maintenance schedules, medical practices—the list went on and on.

It had also been a fight to scale the strategic application platform and private cloud environment, but that had proven worthwhile, too. Jane had made the case for the investments based on cost, flexibility, and time to market, but she had an ulterior motive: she wanted to build security into the platform, so that you’d have to work to make a new program insecure. The transparency into their hosting environment provided by their private cloud had helped them identify the compromised system quickly today.

Because of the application platform and the cloud environment (and the lack of security-related holdups before deployment), the team had been able to build the back end for the new Mobile Clinical Experience far quicker than it would have taken even a few years ago. Jane had reinvested some of the savings to hire ergonomic specialists to sit with the doctors, figure out how they would use the new tool, and devise authentication techniques that wouldn’t feel intrusive.

“Even though they didn’t get any sensitive data,” Frank said, interrupting her thoughts, “we still stood up the incident war room. It helped us make sure that no misinformation got out to regulators, customers, or the press.”

Jane put her hand on Frank’s shoulder and walked him toward the door, gently encouraging him out of her office. She had other things to worry about that afternoon as well.

This is the state we think everyone reading this book should aspire to. It is not a perfect world without cyber-attacks—that is as unrealistic as New York without pickpocketing—but it is a world in which businesses and organizations are able to deliver the maximum benefits of technological advances without becoming entangled in a scrappy fight with hackers or jeopardizing their business models.

The rest of this book is about what it will take to get there—about how we can collectively push for digital resilience to be the scenario that prevails. It will not happen without action. Ultimately, there are two drivers: a fundamental change in cybersecurity operating models that institutions use to protect themselves, and a generally benign broader cybersecurity environment.

Fundamental Change in Cybersecurity Operating Models

In response to more challenging threats, most institutions would put in “control function”–type operating models. Previously, cybersecurity had been underfunded and companies had little insight into technology vulnerabilities. What protections existed focused on the perimeter. There were few consequences for violating policies, and insecure application code and infrastructure configurations were more common than not.

Between 2007 and 2013, especially as companies continued the process of consolidating and professionalizing IT, cybersecurity grew as a control function. Companies strengthened governance authority for the IT security team, especially for anything related to compliance in regulated industries. They locked down the end-user environment and introduced architecture reviews to reduce the risks in application development and infrastructure projects.

CIOs, CISOs, and chief technology officers we spoke to made clear that most institutions still use this model today, even though it is increasingly unsustainable. It places the responsibility for security mostly on the security team without taking the bigger picture into account. It doesn’t focus protection on the most important assets. It frustrates end users and creates increasing tension between security and innovation. It is backward looking, protecting against yesterday’s attacks, not those of tomorrow. It is also dependent on manual interventions and therefore does not scale well as the threat intensifies.

Our interviews made it equally clear that for the digital resilience scenario to come to fruition, institutions would have to change this model. Cybersecurity would have to be embedded in broader business and IT processes if companies are to protect themselves from escalating threats without destroying their ability to derive value from technology innovation.

There was consensus on the three types of changes that companies need to make in order to get to the required cybersecurity operating model:

- Business process changes, including prioritizing information assets and business risks, enlisting the assistance of frontline personnel, integrating cybersecurity into broader management processes, and integrating incident response across business functions.

- Broader IT changes, including building security into every part of the technology stack as opposed to “layering it on top.”

- Cybersecurity operational changes, including providing differential protection for the most important information assets and deploying active defenses to engage attackers.

Technology executives told us that almost all of these changes would be game changers or have significant impact in reducing the risk of cyber-attack to their organization. The only exception was changing frontline personnel behavior, which many told us would be transformative if it could happen, but given the challenges in changing user behavior, it was far from clear that it would happen.

Worryingly, most technology executives told us that they were not making acceptable progress along any dimension. On average, they gave themselves C and C– scores on progress to date (Figure 2.5).

FIGURE 2.5 Technology Executives Realize They Have Substantial Room for Improvement in Addressing Digital Resilience Levers

Critically, the biggest difference between those institutions that are making relatively fast progress and the others was not funding; rather, it was the level of top management engagement and support.

Benign Broader Cybersecurity Environment

Alongside the active changes that companies must make, many other things would have to not happen for the resiliency scenario to come to pass. Regulators would have to avoid providing prescriptive mandates that focus companies on compliance rather than reducing business risks. Countries would have to refrain from imposing restrictive standards on data location and local technology sourcing that could fracture the Internet into a series of “splinternets.” Countries would also have to avoid the type of accusations and rhetoric about cyber-warfare that could discourage multinational cooperation.

There is, of course, also a set of positive actions that national and international bodies could take to promote a more benign, broader cybersecurity environment. However, there is much less consensus on which specific levers will have the most impact than there is on how individual institutions can protect themselves. For every CISO who wants more public investment in basic cybersecurity research, another expressed doubt that the public sector could make effective investment choices.

Although the waters may be muddier, we believe that there are actions that, thoughtfully applied, could help bring about digital resilience. Major states could provide more transparency into their national cybersecurity strategies, there could be some harmonization of cybersecurity regulation across major economies, and law enforcement and private enterprise could cooperate more to improve information sharing.

In the area of community action, industry groups such as the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC) could facilitate more joint research, share more intelligence across institutions, and potentially create shared industry utilities for common cybersecurity functions.

Realizing the Full Value

Building digital resilience will enable institutions to break free of the seemingly impossible cybersecurity trade-offs they face today. They will be able to dramatically reduce the risks of losing intellectual property or sensitive data and absorb any disruption to technology-enabled business processes while still capturing the full value from information technology.

Countering cyber-attacks would no longer mean creating an unproductive user experience, nor would it slow down the introduction of innovation technologies.

In the digital resilience scenario, society captures the $8 trillion to $18 trillion in annual value possible from the mobile Internet, the Internet of Things, cloud computing, and other innovation technologies. If we fail to achieve digital resilience, every month’s delay caused by cybersecurity issues means leaving money—and tangible benefits for the world’s population—on the table.

● ● ●

The threat of cyber-attack is a daunting issue. The combination of valuable online assets, open and interconnected networks, and sophisticated attackers has propelled cybersecurity up the agenda. Unfortunately, most companies do not yet have the capabilities in place to protect themselves while continuing to innovate rapidly and expand the value they derive from technology investments.

Over the next several years, the situation could get a lot better—or a lot worse, with as much as $3 trillion at stake between the best and worst scenarios. This divergence in outcomes emphasizes the importance of companies casting aside traditional siloed and reactive cybersecurity models and building the capabilities required for digital resilience. It also emphasizes the need for other participants in the cybersecurity ecosystem—especially regulators, policymakers, and technology vendors—to support companies in these aims.