3

Prioritize Risks and Target Protections

With no natural defenses and fewer troops than his enemies, Frederick the Great admonished his generals, “Little minds try to defend everything at once, but sensible people look at the main point only; they parry the worst blows and stand a little hurt if thereby they avoid a greater one. If you try to hold everything, you hold nothing.”

What holds true for Prussian commanders applies no less to business and technology leaders scrambling to protect their companies from cyber-attack. Just as generals must husband scarce divisions for their country’s most pressing threats, CISOs must focus their resources on their company’s most critical business risks.

Before anything else, achieving digital resilience requires companies to pull two levers successfully. They must prioritize information assets based on business risks and provide differentiated protection for the most important assets.

Too many companies fail to do this. They have limited insight into which information assets are most important and cannot put more stringent protections in place to defend those critical assets. The result: the company gets too little protection for too much money.

The businesses, the risk function, IT, and the cybersecurity group all need a common language and set of mechanisms to assess risks, evaluate potential protections, and make trade-offs.

In prioritizing information assets, cybersecurity teams must balance rigor with practicality and ensure that senior business executives can understand the choices and implications. Once they progress from prioritization to selecting the right mix of protections, it is important to think about the potential set of controls in a holistic way. Companies that get this right find the results extremely powerful. They discover important assets and risks they had not thought about. They find that some assets, such as marketing data, are less critical than they thought. Eventually, they arrive at a combination of controls that reduces their risk, with the minimum impact on the business.

Naturally, input from business executives in identifying information assets, assessing business risks, and making decisions about the right balance between risk, cost, and business impact will be critical to success here.

UNTARGETED SECURITY MEASURES SERVE ONLY ATTACKERS

An information asset is data that has business value for the enterprise. The asset is not a particular application or database or server, but rather the information they store and use, such as customer data, pricing information, underwriting methodologies, or engine designs.

A security control is a measure that mitigates risk. Many controls involve cybersecurity technologies: firewalls keep unauthorized traffic off a corporate network; encryption protects data from those who lack the authority to access it. Some controls are policies that affect the broader IT environment, such as standards developers should use to reduce the likelihood of security flaws in their code. Others are policies about business processes, such as which data should be purged after a period of time.

Figuring out which assets and risks are most important and what controls to put in place is tough.

Companies have to protect themselves against an expansive array of risks that are hard to assess. For machinery accidents, credit card defaults, or worker’s compensation claims, there are quantitative data about the historical frequency and impact of these events. This allows companies to make intelligent, fact-based decisions about the relative importance of various risks and how much to spend mitigating them.

Unfortunately, this does not typically hold true for cyber-attacks. The loss of sensitive intellectual property (IP) to a foreign competitor, the release of confidential customer information on the Internet, and the disruption of online customer care for days on end are all extremely worrying prospects for most companies, but which one is most important? Historical data about the impact and likelihood of breaches are sparse and often not available in a format that supports statistical analysis.

Even if companies were less reticent about sharing what information on attacks they do have, attackers are evolving their strategies so rapidly that these experiences may not be relevant. Some risks are catastrophic events so unusual that they would not be addressed by historical data. In other cases, the impact of an event is necessarily contingent and uncertain: a foreign competitor might steal information about proprietary manufacturing techniques, but will it have the requisite expertise to exploit that information? It is impossible to know for sure.

Discussions on what to protect and how to protect it can end up with unhelpful resolutions such as “give us the best protection you can,” or “we can’t tolerate any loss of data.” This puts the decision-making onus onto a CISO, who lacks the power to push back on changing investment priorities and the knowledge about what information assets the company has and how valuable they are to both the business and attackers.

Even banks struggle to get this process right, despite the regulatory pressure they face to implement documented governance processes. In some cases, banks have identified cyber-risks in their enterprise risk register, but the register itself lacks stakeholder buy-in, so it cannot be used to drive cybersecurity policy or investment. In many cases, identifying banking risks has become very compliance oriented—more focused on following a process than on generating actionable insights that can drive cybersecurity decisions.

The result of these challenges is that many CISOs have fallen back on one of three approaches: protect everything to the same level, focus on whatever has generated the most noise from senior management, or determine protection on an ad-hoc basis.

Protecting all information assets equally dates from the era of perimeter protection. As one CIO told us, his environment was “hard on the outside, but soft and chewy on the inside.” His organization had invested for years in firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and other controls designed to keep attackers off its network, but had sought to minimize complexity by devoting much less effort to securing individual systems within the corporate data center. Ten years ago this strategy probably made sense, but it is now untenable, with more determined attackers, mobile technology, and pervasive digitization creating more ways into corporate networks. Even if the perimeter is not as dead as some have claimed,1 it can no longer be the sole line of defense protecting the enterprise.

In any event, a homogeneous level of protection can be expensive and unnecessary. A heavy manufacturing company spent years debating whether to disconnect or “air gap” all of its plants from the corporate network. The cybersecurity team argued that an air gap would be best practice given the production control systems in each plant. The IT infrastructure team countered that the complexity created by disconnecting the plants from the corporate network would require hundreds of millions of dollars in additional expenditure. Senior management struggled to adjudicate between the competing, technically arcane arguments. Finally, the company started to tease apart the different risks in different plants. It found that a cyber-attack on a production control system could theoretically cause a catastrophic event at only a small fraction of the company’s plants. A line stoppage was the worst that could happen at the remainder. Based on this analysis, the company air gapped only about 10 percent of its plants from the corporate network, dramatically reducing the expenditure required without jeopardizing the company’s operations.

Controls are not always inadequate; they can also be excessive. An aerospace company applied the same document control policies and technical restrictions on sales and marketing materials as it did for confidential engineering documents. As a result, multiple approvals were needed just to share marketing content with external parties, enforced by the file-level access rules in its collaboration platform. This process could take weeks, which led to missed opportunities to share materials that had already been designed for external distribution, for example, for trade shows, sales meetings, and press conferences. In one often-discussed case, the marketing team showed up to a conference completely empty-handed. Once the materials were properly classified as intended for public consumption, the access control restrictions were lifted, and the marketing team could respond to requests much more promptly.

Rather than try and protect everything equally, some companies focus protection on a small subset of assets and risks based not on rigorous analysis but on incomplete and sometimes emotional input from senior management. This usually results in major risks being left unaddressed. For example, a bank had suffered major operational outages driven by distributed denial of service attacks. Therefore, the lion’s share of additional cybersecurity investments was directed at preventing attacks of the same nature. However, this led to the bank underinvesting in protecting itself from other types of attacks (e.g., fraud and insider threats). This problem is particularly acute where customer data are deemed disproportionately important—institutions become so focused on protecting customer information that they all but ignore other types of important data such as corporate strategy information or business process data.

The final common but flawed approach is for companies to try and focus their controls on the most important information assets but in an unsystematic way with limited or ineffective input from the business. An insurer left cybersecurity investments almost entirely to the discretion of the CISO. The result was that the level of security controls bore no relationship to what the business thought were the most important assets to protect or to its tolerance for the impact the controls had on user experience. The security team felt isolated from the rest of the business, and whenever it asked for more money to cover a specific need, the business leaders had no way to judge whether the additional spend was justified.

PRIORITIZE INFORMATION ASSETS AND RISKS IN A WAY THAT ENGAGES BUSINESS LEADERS

Only a few companies have cracked the code of bringing together the business, risk, IT, and cybersecurity to identify and prioritize risks using a common frame of reference.

Business executives in the organizations that get cybersecurity right understand the value-at-risk from cyber-attacks and the value of selected, high-impact cybersecurity initiatives. They understand which information assets are most important and that the risk of those assets being exposed should drive the level of protection and therefore the investment allotted. In these organizations, cybersecurity executives have meaningful and fruitful discussions with the business on the benefits of various mitigating options and on the implications of accepting the risks rather than investing in mitigation. Cybersecurity leaders help the business take tough trade-off decisions, and have the authority to supervise the implementation of the initiatives with IT and with the business, and escalate where there are roadblocks and delays. The CIO is comfortable justifying the security spend in terms of its contribution to the organization’s security and can defend it as part of the overall portfolio of IT initiatives.

There are three specific aspects of a successful information asset prioritization program: defining the assets and risks in business terms, engaging senior business leaders, and diving deep into the long-tail risks.

Define Assets and Risks in Business Terms

It is easy for CISOs and their teams to think about risks in technical terms given cybersecurity’s history as a technical discipline. However, to make sure they surface the full set of risks and engage business leaders effectively, cybersecurity teams need to build their prioritization efforts around business concepts, rather than technology.

Focus on Information Assets Rather than Data Elements

When asked about prioritizing information assets, many CISOs will say they have a data classification program. That means they have a team going through every field in every database and categorizing each one as “restricted,” “confidential,” “internal,” or “public”—typically over the course of two to three years. This type of approach is great in theory, but in practice it often excludes important unstructured data that live outside databases; and attackers are unlikely to wait politely for three years while a company finishes its classification program. To address the full set of data and derive a set of insights they can act on, cybersecurity teams need to start at a higher level of abstraction and look at information assets rather than fields or tables in databases.

An information asset is a coherent body of information that has recognizable and manageable business value and that is defined by business needs and objectives rather than the specifics of how and where it is stored. As noted earlier, it is not a system, a database, or an application. It could be customer information for a consumer auto business, business plans for upcoming mobile products, or manufacturing specifications for paint application. The assets will vary by business, and the importance of different types of assets will also vary.

There is no hard-and-fast rule about the right level of granularity for an information asset—for example, should manufacturing specifications for 10 different products in a given business unit be treated as 1 information asset or 10? That said, there are two heuristics for answering such questions: materiality and distinction. Which of the products are big enough to matter? Are there enough business differences among the products so their manufacturing specifications will have different levels of sensitivity?

Typically, a business will have between 25 and about 80 information assets, depending on its size and complexity. Table 3.1 shows a typical list of assets for an insurance company.

TABLE 3.1 Information Assets Span All Functions—Insurance Example

| Function | Assets |

| Finance | Account data Securities Payment data Tax records |

| Investment management | Strategic asset allocation Tactical asset allocation |

| Human resources | Employee data records Applicant data records |

| Audit | Audit reports |

| Legal | Compliance data Specific lawsuit data Legally mandated data |

| CEO function | Board/management documents (decisions, business plans, strategies) |

| Market management | Customer segmentation Customer value Marketing plans |

| Products, actuarial, reinsurance | Product and risk model (including historic database) Product road maps Customer name/address data |

| Sales/distribution | Customer financial data (including credit card data) Private customer personal data Business customer inside data |

| Policy management/underwriting | Contract information and risk assessment Contract appendices (e.g., power plant plans) |

| Claims management | Claims Expert reports (legal, medical) |

| IT | System access logs Identity/access/authorization data IT architecture blueprints and source code |

| Operations support | Facility access logs Provider/vendor costs |

Assess Business Risks, Not Technology Risks

When we ask a CISO what risks he is worried about at the moment, he is likely to say, “Ten percent of our servers are running on an operating system that’s about to go off support. Our network is almost entirely flat, so I can’t slow down attackers once they get in. And did I mention our developers’ buggy insecure code?” These are all incredibly important vulnerabilities that almost certainly need to be addressed, but in what order? And which applications with buggy, insecure code should be tackled first? It is impossible to answer this without having a sense of what information assets the application might use, who the attackers might be, and what business harm could result.

A business risk is the combination of:

- A valuable information asset (e.g., personal health information, a manufacturing process for a new product)

- An attacker (e.g., organized cyber-criminals, state-sponsored actor)

- A business impact (e.g., regulatory or legal exposure, industrial espionage)

A business risk for a health care provider therefore might be regulatory and legal exposure as a result of cyber-criminals stealing patient medical data. For a technology provider, it might be the loss of competitive advantage after a state-sponsored attacker steals a manufacturing process and sells it to a competitor.

Companies find it much easier to think about impact and likelihood in terms of business risks than for technology risks or vulnerabilities. Perhaps more importantly, senior executives find business risks to be a tangible way to engage on cybersecurity.

Proactively Engage Senior Leaders

Prioritizing business risks and information assets means answering some strategic questions: How would customers react if a company allowed attackers to steal their personal data? How much would a foreign competitor benefit from access to a product’s underlying IP (and how would that affect the product’s growth and margin expectations)? How would regulators react to a public breach? Addressing questions such as these requires a fact-based, detailed discussion between the cybersecurity team and senior business managers with each group seeing the other as equals.

Start with a Hypothesis

When CISOs ask senior business leaders what cybersecurity risks worry them, they seldom receive deep, thoughtful answers based on underlying business drivers. More commonly, the answers are along the lines of “I hadn’t really thought about that” or “Customer information is most important, I guess.” Answers like these highlight why the cybersecurity team cannot just listen and record the business perspective—it must develop its own hypotheses and engage business leaders as peers.

Use Value Chain and Risk Classification

A business value chain identifies each step in important processes. In insurance, for example, these would be origination, underwriting, servicing, and claims. For each step, a classification of business risks reveals important questions to ask:

- Are there data associated with this step in the value chain that would cause reputational damage if publically exposed?

- What IP does this step use that might be valuable to competitors?

- What sensitive business information could be disclosed about this step?

- What are the opportunities for cyber-fraud?

- What is the potential for business disruption or data corruption?

- What regulatory actions could occur?

This exercise helps the cybersecurity team develop a first view on what business risks and information assets it needs to raise with business leaders. It also helps ensure that important issues are not missed in the process. Figure 3.1 shows how this mapping clearly flags the priority risks.

FIGURE 3.1 Rank Types of Risk across the Value Chain to Help Engage Business Leaders

Ground Discussions in Underlying Business Drivers

The question of which risks to which information assets matter most has to be based on underlying business drivers such as scale, share, growth, and competitive position.

For example, one manufacturing company struggled to differentiate the risk of IP being compromised for different products until it started to look at these products’ revenues, margin, and growth. For the first cut, business managers suggested taking a product life-cycle view. Some of the potentially most valuable IP was for new products that had yet to catch on in the market. This led to a discussion about which product value propositions most depended on IP. Ultimately, the cybersecurity team developed a perspective on which IP was most valuable to the company in terms of growth and margins over the coming years.

Taking a similar business perspective also helped a financial institution clarify the value of its pricing information. Many of its businesses said that their pricing information and databases were highly proprietary and that they worried about employees taking copies when they left to work for competitors. However, the markets for some financial products are very liquid, with highly transparent market prices. Other markets are less liquid and prices vary quite a lot. The less liquid the market, the more valuable the pricing data is as an information asset and the greater priority it needs.

Remember that the Enemy Gets a Vote

Any discussion of business risks has to include a perspective on whether there is a credible attacker with the capabilities and motivation to compromise and exploit an information asset. If a company has a valuable piece of IP that it has invested hundreds of millions of dollars developing, then this is clearly a valuable information asset, but that does not necessarily mean that there is a large business risk associated with it. The cybersecurity team has to talk to business managers to find out whether executives at traditional competitors would be willing to commission a cyber-attack to steal the IP and risk exposure and prosecution to pick up a few points of market share. A competitor from another country might be more aggressive if it were less likely to be prosecuted, but cybersecurity teams and business managers must then consider whether it would have the expertise to take advantage of the IP within a reasonable time frame?

Use Pragmatic and Transparent Decision-Making Criteria

Nobody has yet developed a robust, usable, generally applicable model for the expected economic impact of different types of cyber-attacks. However, that does not mean companies should make cybersecurity investment and policy decisions based purely on subjective inputs.

A scorecard-based approach provides a workable mix of feasibility and rigor. For any given business risk, the impact can be scored in terms of the company’s reputation, competitive position, economic losses, and regulatory impact. For example, a financial impact of less than $100 million might be considered low impact; between $100 million and $1 billion medium impact, and anything more than $1 billion high impact. From a reputational standpoint, a breach likely to be reported only in trade publications would be low impact, but one that might reach the front page of regional or national newspapers would be high impact. In terms of regulation, a low-impact event might result in regulatory inquiries but no findings, a medium impact event may have findings but a clear path to remediation, while a high-impact event would be one with a substantial negative impact on a company’s relationship with the regulator.

Alongside impact, cybersecurity teams can score the likelihood of an attack as low, medium, or high in terms of:

- User exposure: Number and type of users who have access to the system (e.g., internal users only, suppliers, customers, semipublic, public).

- System exposure: Number and type of systems on which an information asset sits or passes through.

- Vulnerability: Quality and extent of existing controls.

- Attacker: Value to potential attackers and the capabilities of likely attackers.

Using these criteria, companies can stratify risks according to expected impact (Figure 3.2). Done well, this can have a transformational impact. Broad alignment on the most important business risks can shape every cybersecurity decision, from how to structure the organization to where to deploy resources and which technologies to invest in. Even more directly, more stringent controls can be put in place to protect the most important information assets where the business risk is considered critical.

FIGURE 3.2 Plotting Risk Likelihood against Impact Helps Drive Decisions about Cybersecurity Investments

Perform Deep Dives for “Long-Tail” Risks

Stratifying business risks by impact and likelihood is hugely beneficial and allows companies to make practical decisions about policies and controls. However, some business risks are so severe that they require special consideration, in part because there may be little to no historical data or any experience at all from which to evaluate the impact of such an event.

In these cases, full event scenario analysis can help companies understand the investments required to prevent or mitigate such an attack. It may even be a regulatory requirement, for example, to determine the necessary capital reserve levels for a bank.

Event scenario analysis is the process of identifying, understanding, and evaluating a company’s exposure to and ability to respond to extremely large or serious events that could plausibly occur given the nature of the organization’s activities. These events are typically low in frequency or probability but high in severity.

The company must first define the high-level story it is investigating. For a bank, the story might be that a political hacktivist group, perhaps with ties to an unfriendly foreign government, is trying to disrupt and corrupt trading operations in order to inflict economic damage to the broader economy.

The bank must then define types of impact. The simple direct impact of the proprietary trading desk being out of the market can be measured in dollars per minute multiplied by the number of minutes the system is down. However, the longer the bank is out, the more the market becomes aware of the situation and starts to trade against the bank and its positions. So the relationship between direct cost and time is not linear. Then there are potential legal implications for corporate client trading, and possibly goodwill compensation to pay as well as direct compensation to manage reputational impact. If the attacker manages to alter data about who made what trade, additional forms of exposure appear.

Next, the bank must put some numbers against these effects. The team needs to decide the extent to which losses grow over time, how much its trading positions move against the bank, what other channels customers have for their assets, how long the breach will be open, and what level of fines they can expect (fines vary enormously but tend to be driven by the number of customers affected and the expected impact on each customer). The output is a consensus estimate of the potential impact of the risk scenario in dollars.

The final stage is to launch a process that creates specific business, technology, and security recommendations that can mitigate the potential economic loss.

PROVIDE DIFFERENTIATED PROTECTION FOR THE MOST IMPORTANT ASSETS

Knowing which business risks are most pressing and which information assets are most important is good but yields only conceptual benefits. Real protective power comes from moving beyond a one-size-fits-all cybersecurity model and systematically applying a more rigorous combination of controls to protect a company’s most important information assets. This represents a significant change in capabilities for most cybersecurity organizations, and introducing multifactor authentication or encryption at rest for some assets but not all increases complexity. Even organizations that have already applied some more rigorous controls rarely do so in a consistent, systematic way that is aligned with a company’s most critical business risks. Getting this right requires a new level of coordination across business, IT, and cybersecurity.

There are four elements to effective differentiated protection: layering more rigorous controls on top of basic security measures, mapping the priority assets to systems, using the full range of controls and grouping them into tiers, and evaluating how different controls work together to minimize the impact on users.

Selectively Layer Enhanced Controls on Top of a Baseline Level of Security

Differentiated protection for a company’s most important information assets supplements, rather than replaces, an effective baseline of protection that spans the entire environment. Firewalls, web filtering tools, and intrusion detection systems have to keep out inappropriate traffic and protect all information assets. Identity and access management (I&AM) capabilities have to prevent unauthorized users from accessing the corporate network. The security operations center must monitor the environment for anomalous events that could indicate an attack. All these capabilities have to be in place before a company thinks about differentiated protection.

While many aspects of cybersecurity are highly dependent on an individual company’s mix of businesses, information assets, and technology strategies, baseline levels of protection are more standardized. Benchmarking basic controls against peers can therefore give a company a rough sense of whether it has the right level of protection.

For example, when a pharmaceutical company compared its basic level of security to its peers, it found troubling gaps. Dozens of sites lacked appropriate firewall protection; hundreds of applications ran outdated, insecure hardware; and many businesses lacked even the most rudimentary password discipline. As a foundation for putting differentiated protections in place, the company had to do the hard work of going site-by-site, business-by-business to close these gaps in its basic protection.

Map Information Assets to Technology Systems

No CISO, no matter how innovative, can apply technology controls directly to an information asset. Differentiated controls such as more stringent password requirements and encryption are applied to systems like applications and databases.

Cybersecurity teams therefore must work with application development teams and other IT stakeholders to identify all the systems that touch each priority information asset. This need not be complicated. The IT group in one bank (in particular, the head of infrastructure, the lead architect, the chief data officer, and the main application owners), filled in a simple matrix that had the bank’s systems and applications on one axis and the assets on the other. This low-tech solution was both faster and more reliable than turning to the bank’s official asset inventory, which was already out of date. Rather than try to update the inventory as part of this project, the CIO realized that 100 percent accuracy was likely to remain elusive and 95 percent would be good enough for the purposes of this exercise and to maintain the momentum of the whole project.

Life in IT would be simpler if each information asset could be associated with a single application or system. In reality, most companies find that some assets are distributed widely across IT systems—some managed internally and some owned by vendors. In particular, customer data are often stored in several systems, including a central customer database, a customer relationship management system, billing system, trouble ticketing system, and several data warehouses. They are also managed in smaller sets within a number of satellite systems and user devices that are difficult to map and even harder to keep track of.

As a result, cybersecurity teams need to focus on the systems that have the most significant concentrations of information assets. One bank found that 20 percent of its applications held more than 80 percent of the occurrences of its high-priority information assets. It therefore decided to focus its implementation of differentiated protections on that 20 percent of applications.

USE FULL RANGE OF CONTROLS BUT ORGANIZE INTO TIERS

Even savvy technology executives may instinctively believe that differentiated protection means tighter password controls and more extensive encryption. Naturally, it does, but there is a much broader set of options available. Cybersecurity teams should consider the full gamut of options (Table 3.2), which will help them defend priority information assets against a wider range of sophisticated attacks.

TABLE 3.2 Differentiated Controls Span Business Processes, IT, and Cybersecurity

| Type of Control | Area | Examples of Differentiated Controls |

| Business process | Access management | More stringent requirements for authentication and authorization More frequent access rights reviews |

| Data management | Accelerated purging | |

| Vendor management | More thorough vendor assessments More stringent requirements built into contracts Limitations on data that can be shared with vendors More frequent audits of vendor compliance |

|

| People management | Secure paths through core processes Targeted surveillance of insiders Targeted training |

|

| Human resources | Enhanced background checks and monitoring | |

| Broader IT | Document management | Mandatory use of document management systems Digital rights management (DRM) for files containing priority information assets |

| Application security | More extensive security reviews for application development projects More frequent vulnerability scanning and penetration testing |

|

| Client security | Expanded use of desktop virtualization | |

| System security | More frequent security patching | |

| Network security | Use of higher-security network segments | |

| Cybersecurity | Identity management | Multifactor authentication More rigorous password policies |

| Data protection | Encryption in motion Encryption at rest |

|

| Data loss protection (DLP) | DLP rules and file tagging targeted at priority information assets | |

| Perimeter security | More restrictive firewall rules | |

| Incident response | More rapid escalations | |

| End-point security | Transition from blacklist to whitelist model |

At another institution, the senior IT leadership team proudly pointed out that it had a “fit for purpose” control strategy; it had figured out the appropriate mix of controls based on the sensitivity of the data associated with the application. When prodded, the team acknowledged that, for the most part, individual application owners made decisions about what “fit for purpose” meant and that the approach had introduced a fair bit of complexity into the environment. It also meant developers and system administrators had to do considerable research into any application before updating it to make sure they would not break something in the security model.

Assuming they are not using the same types of controls everywhere, companies often find a fair degree of randomness when they look at the controls deployed across applications. One industrial company found almost no correlation in its applications between stringency of controls and sensitivity of data housed.

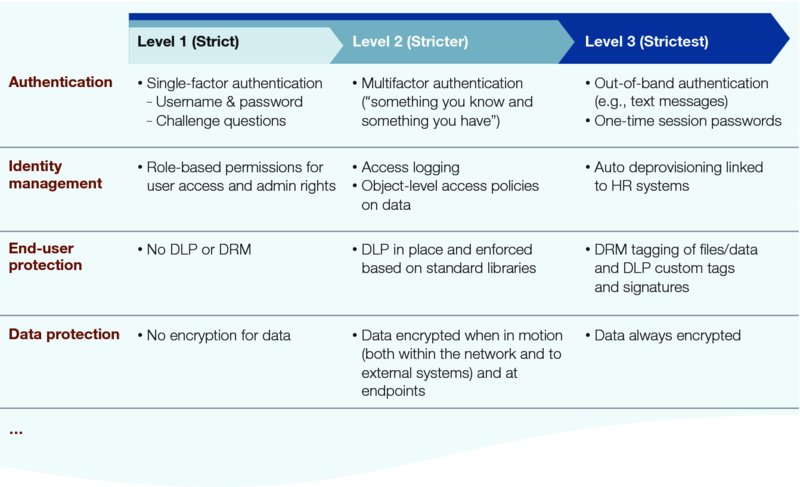

Most controls can be applied at varying degrees for a tighter or more relaxed security level. Authentication controls at their most basic, for example, are simple user name and password forms. At the next level, multifactor authentication introduces the “something you know” (password) and “something you have” (e.g., a token) concept. At the most complex level, they use “out-of-band authentication,” where passwords might be valid for only one session and users need to authenticate using an additional entirely separate channel, such as sending a text message (Figure 3.3). The tighter the controls, the greater the impact on the user experience, as well as on the setup and operating cost and maintenance. Cybersecurity teams can help business leaders understand gradated controls in a simple framework that lays out three or four levels of rigor for each type of control.

FIGURE 3.3 The Same Controls Can Be Retuned for Optimal Protection

Evaluate Different Combinations of Controls

CISOs and their teams should create combinations of controls that mutually reinforce each other. Combining controls also allows cybersecurity teams to analyze the aggregate security and convenience impact for each application or class of applications. Different mixes of controls can provide the same level of end protection but the impact on user experience, cost, and maintenance can vary widely.

Tighter, more restrictive controls can definitely reduce risk but there are trade-offs. Stringent I&AM controls can limit insiders’ (including contractors) access to priority assets but also absorb significant administrative and user time; data loss protection (DLP) tools can reduce the ease of stealing valuable data, even after penetration, but every additional layer of protection adds friction to everyday logins. More thorough logging and detailed network inspections make it easier to spot a breach, but real-time monitoring can absorb system resources and slow applications. Even more thorough background checks before hiring can meaningfully reduce the risk, yet are costly and slow down the recruitment process. It is therefore imperative to get the right set of controls that deliver protection where needed without damaging the user experience too greatly.

One manufacturing company needed to increase protection for applications that held valuable IP. The security team held a series of workshops with business leaders and application owners about which types of controls they thought would be ideal for their underlying assets and how they might work together at different layers. The group agreed that given the highly sophisticated attacks they faced, simply installing better firewalls was unlikely to be sufficient.

Instead, it looked at a range of controls that would work together and help the company understand and prevent certain types of losses with relatively minimal impact on employees. It increased the use of multifactor authentication and the level of log retention and analysis, and introduced new digital loss prevention software. Employees already had access cards, so using them for digital authentication meant it did not need to distribute and manage a new set of security devices. Most visitors were on-site more than once, so the effort spent registering their computers would pay off over time. The team even addressed the patching regime (the process of fixing known vulnerabilities), which had essentially been arbitrary but now moved to a risk-based approach that was welcomed by the business. Evaluating these trade-offs early and paying particular attention to the end-user experience made it much easier for users to accept the new protection model.

DELIVERING TARGETED PROTECTION OF PRIORITY ASSETS IN PRACTICE

Aligning on the prioritized information assets and business risks and using them to put in place a differentiated set of protections may sound conceptually simple, but it requires real effort and discipline.

Imagine that in light of a minor breach, a medium-sized auto parts supplier realized that it had to understand its cybersecurity risks better and started to orient its protections around them. Based on the levers we have described, it could use a three-phase process: preparation and data collection, asset and risk assessment, and defining and implementing differentiated protection.

Phase 1: Prepare and Collect Data

The CIO and CISO would use this preparatory phase to get all the preconditions for success in place. The CIO would make sure she had senior management’s backing for the effort and would then spend time with the executives responsible for each of the major business units and enabling functions, explaining the effort, getting input on whom to interview, and asking for points of contact in each area.

In a larger company, the CIO and CISO would probably start with one or two pilot businesses so they could show progress and refine their approach before moving on to the next one. In this case, however, the CIO and CISO agree that the company’s moderate size and straightforward business model allow them to cover the entire business in one wave.

The CIO would also convene a working group of herself, the CISO, and representatives from each of the business product lines and functions to ensure access to data, check progress and review analyses, and deliver recommendations. Meanwhile, the CISO would work with each of the business unit CIOs and their teams to assemble all the data required, especially catalogs of applications in each business, along with any available information on supported processes, risk classifications, and technical configurations.

Phase 2: Assess Risks and Assets

The CISO and his team would use this phase to capture and prioritize the full set of information assets and business risks.

Step 1: Identify Assets across the Value Chain

The group’s first task would be to discover what the critical information assets were. The team would look at the business processes that occurred along the value chain—product development, marketing, sales, and after-sales service—and develop a set of hypotheses about the important information assets at each step. At that point, the CISO would sit down with senior executives from each business area and rather than just ask what keeps them awake at night, he would test the hypotheses his team developed and use them to get a better understanding of which information assets might be most important.

For example, the head of sales might explain that the company gets incredibly sensitive forecasts and specifications from its auto manufacturer customers as part of the process of bidding to supply a subsystem for a new vehicle under development. If the manufacturer believed that such information could be compromised, the impact on the supplier would be devastating from a business standpoint. By contrast, sales forecasts related to models already in production might be much less sensitive because competitors could already estimate this from existing publicly available projections.

Step 2: Analyze the Risk and Prioritize the Assets

The company would now have a good list of important information assets but would not yet understand the risks. Based on their discussions with business leaders, the CISO and his team would ask themselves about the impact on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of each information asset should it be compromised. They would score each combination of compromise and asset in terms of competitive disadvantage, customer impact, reputation impact, fraud loss, regulatory exposure, and legal exposure. This would take into account issues such as the underlying product economics and competitive pressures (e.g., the impact of losing IP underpinning a marginal product might be quite low).

They would now take the attackers’ perspective and try to understand who would benefit from compromising important information assets and whether those who would benefit have both the incentives and the capabilities to act on any information they extract. A traditional competitor would benefit from understanding a company’s manufacturing processes, but executives might not be willing to risk destroying their careers and forfeiting their freedom to take advantage of that information now. A new market entrant might be less worried about prosecution but might lack the expertise to take advantage of sophisticated manufacturing techniques. The CISO and his team would also know that not all attackers are external and that insiders often take sensitive product and pricing information with them when they start jobs at competitors, which they also need to factor into their decisions. The team would complement this attackers’ view with high-level perspectives on the current level of exposure. For each asset, they would ask how many people have access to it and whether it has already been targeted for more restrictive controls.

Based on this analysis and a structured set of criteria, the team would now have a prioritized list of information assets. These would likely be stratified into a few categories, for example, crown jewels, restricted data, baseline data, and public data. It could also synthesize a prioritized list of business risks stratified by business impact and likelihood. Both would be invaluable in communicating its findings with business leaders. The team would conduct one or more workshops with its partners in the business to test its findings and reprioritize the risks and information assets as required.

Phase 3: Define and Implement Differentiated Protections

Step 1: Evaluate Current Level of Protection

The team cannot apply protections directly to information assets, so they would need to determine which systems house priority information assets and what protections were already in place on those systems.

First, it would define three or four levels of rigor for each major type of control—I&AM, data protection, DLP and digital rights management (DRM), application security, infrastructure security, network security, vendor management, and others. Then it could launch a survey of application development managers asking them to map the priority information assets to systems and to score each system in terms of the rigor of each type of control applied.

This would enable the CISO to answer several important questions, such as:

- How rigorous is each type of control (e.g., do most applications use single-factor or dual-factor authentication?)

- Are the most important information assets protected by more rigorous controls?

- What drives choices about controls—do some parts of IT use more rigorous controls, regardless of whether the system houses the most sensitive information assets?

Step 2: Define Future Protection Levels

Four levels of rigor, even for only six control areas, would result in more than 4,000 distinct control combinations. Therefore, the CISO and his team would need to create bundles of controls.

If they wanted to be very simple, they would define one bundle of controls for the crown jewels—the company’s most important information assets—one for restricted information, one that would be for the baseline, and one for public or less important data. However, they might decide to have variations of each bundle for structured data (e.g., customer order history and other information found in databases) and unstructured data (e.g., proposals and other data stored in documents). In defining the bundles, the CISO would use existing technologies and capabilities as much as possible but might conclude that some new capabilities are required (e.g., out-of-band authentication). In all cases, the team would assess the effect of each bundle of controls to ensure that any additional impact on user experience made sense in the context of reducing the risk, and then validate this using focus groups, demos, and other techniques.

Finally, the team would use the classification of information assets and the mapping of information assets to systems to define which bundle of controls needs to be applied to which system.

Step 3: Transition to Implementation

Once the CISO has identified the optimum levels of protection, his team needs to assess what they and others have to do to put these controls in place. In some cases, the change will be a simple policy or process change—vendors that handle a certain type of information asset will need a more thorough assessment; passwords for applications that house a certain type of information asset will need to be changed more frequently.

In many cases, the company will already have the underlying security capability, but a system might need to be adjusted to adopt it. The company might have tools that support multifactor authentication, for example, but many systems may need enhancing so they can use the company’s latest I&AM platform.

There may be cases where the CISO needs to launch or accelerate the introduction of a new technology or capability. For example, the company might need to implement DRM in order to control who can access documents with data such as product road maps and manufacturing specifications. Therefore, the team would build all the implementation activities into its work plan for the coming year and those of many of its partner organizations.

Finally, the CISO and his team would make sure that they had a documented methodology for prioritizing information assets and putting differentiated controls in place so they could easily repeat the process, reflecting changing business conditions, an evolving attacker environment, and new innovations in defense mechanisms.

● ● ●

Any company, no matter its size or complexity, will have many different types of information assets and face a bewildering array of business risks. No company can protect everything effectively, especially not at a reasonable cost and with acceptable levels of impact to the business.

Therefore, companies have to prioritize. They need to understand their most important information assets and the business risks they face, and they need to use this insight to put more rigorous business process, broader IT, and cybersecurity controls in place to protect these critical information assets.

This cannot be a one-time event. Business models change, creating new types of information assets. Attackers improve, creating new risks and heightening old ones, while state-of-the-art cybersecurity also evolves, creating new options for differentiated controls.

Companies therefore need to put in place repeatable, structured processes that allow the cybersecurity team to engage with the business leaders to discover important information assets, prioritize business risks, and align on differentiated protection. Moreover, these processes should be a critical input to the development of annual cybersecurity budgets and plans.

Input and validation from senior business leaders will be essential. The CEO must set overall expectations about risk appetite, while business unit executives must provide input on identifying information assets, assessing business risks, and validating trade-offs between the risk, cost, and business impact of the different protection options.