CHAPTER 5

Building the User Interface

Chapter 4 introduced the layering and components of Grails, and it showed you how to create a simple application using Grails scaffolding. In this chapter, you'll use the domain objects from Chapter 4 to start the process of creating an attractive, full-featured application.

You will learn how to use GSP, Grails tags, Grails templates, and CSS to create a look and feel that will be common across the application. You will create the login view and controller actions to support it. Once you have some code, you will start building a testing harness that will include integration tests and functional tests. Next, you will start to focus on user experience. You will look at validation, errors, and messages, and you'll learn how to customize them. You'll further enhance the view and controllers by removing unnecessary information, and you'll use actions to set properties on the domain object. To support the application, you will create a simple audit logging facility that leverages the Grails log controller property.

Starting with the End in Mind

The goal for this chapter is to create the look and feel for the Collab-Todo application's layout. Figure 5-1 shows a wireframe to give you an idea of how the application is laid out.

Figure 5-1. The Collab-Todo wireframe

The wireframe follows a common format: two columns centered on the page, gutters on both sides for spacing, and a header and a footer. Table 5-1 describes each component.

Table 5-1. Wireframe Components

| Component | Description |

| gutter | Provides whitespace on the edges of the browser so that the main content area is centered in the browser. |

| topbar | Provides the ability to log in and log out, and displays the user's first and last name when he or she is logged in. |

| header | Displays the application's title, "Collab-Todo." |

| content | This is the main content area of the application. The majority of the application data is displayed here. |

| right sidebar | Chapter 8 will use the right sidebar to display buddy list information. |

| footer | Displays copyright information. |

Like most modern view technologies, Grails uses a layout and template-based approach to assemble the view/UI. A template is a view fragment that resides in the grails-app/views directory and starts with an underscore. The underscore is Grails' convention for signifying that GSP is a template. Best practices dictate that you should put templates that are associated with a specific domain, such as User, in the domain's view directory, such as grails-app/views/user/_someTemplate.gsp. You should put templates that are more generic or shared across views in a common place, such as grails-app/views/common.

A layout assembles the templates and positions them on the page. You create the layout using main.gsp (grails-app/views/layouts/main.gsp) and CSS (web-app/css/main.css). Create a couple of templates (_topbar.gsp and _footer.gsp) that will be common across all views, then apply some CSS styling and leverage it in main.gsp.

Let's start with a simple footer to illustrate the point.

Creating the Footer

The goal is for a simple copyright notice to be displayed at the bottom of every page in the web site. As you might have guessed, you need to create a GSP fragment named _footer.gsp in the grails-app/views/common directory, then add the _footer.gsp template to the layout using the <g:render template="/common/footer" /> tag. You then need to style the footer by adding a <div> section to the main layout using a style class that you define in the main.css. Listing 5-1 shows what you need to do.

You need to add the copyright to the main layout (main.gsp) so that it's included on every page. This is where the <g:render> tag1 comes to your aid. You use the <g:render> tag, which has a template attribute, to insert templates into GSPs. All you have to do is add <g:render template="/common/footer" /> to the bottom of main.gsp. Listing 5-2 shows the content of main.gsp.

Note By convention, the underscore and .gsp are omitted from the template attribute.

Listing 5-2. The Main Layout (main.gsp)

<html>

<head>

<title><g:layoutTitle default="Grails" /></title>

<link rel="stylesheet"

href="${createLinkTo(dir:'css',file:'main.css')}" />

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',

file:'favicon.ico')}" type="image/x-icon" />

<g:layoutHead />

<g:javascript library="application" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="spinner" class="spinner" style="display:none;">

<img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',file:'spinner.gif')}"

alt="Spinner" />

</div>

<div class="logo"><img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',

file:'grails_logo.jpg')}" alt="Grails" /></div>

<g:layoutBody />

<g:render template="/common/footer" />

</body>

</html>

__________

Figure 5-2 shows what happens when you reload the home page.

Figure 5-2. Adding a copyright notice

The copyright footer is on the page, but it isn't really what you want. It would be nice if it were centered and had a separator. You could just put the style information directly in the footer template, but a better solution, and a best practice, is to use CSS.2 You need to add a <div> tag with the id attribute set to "footer" in the main layout, and you need to define the "footer" style in main.css. Listing 5-3 shows the changes you need to make to main.gsp.

__________

Listing 5-3. The Enhanced Main Layout (main.gsp)

<html>

<head>

<title><g:layoutTitle default="Grails" /></title>

<link rel="stylesheet"

href="${createLinkTo(dir:'css',file:'main.css')}" />

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',

file:'favicon.ico')}" type="image/x-icon" />

<g:layoutHead />

<g:javascript library="application" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="spinner" class="spinner" style="display:none;">

<img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',file:'spinner.gif')}"

alt="Spinner" />

</div>

<div class="logo"><img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',

file:'grails_logo.jpg')}" alt="Grails" /></div>

<g:layoutBody />

<div id="footer">

<g:render template="/common/footer" />

</div>

</body>

</html>Listing 5-4 shows how to define the footer style.

Figure 5-3 shows the results.

Figure 5-3. Styling the footer

Let's review how to add the footer. First, you create the _footer.gsp template and locate it in the grails-app/views/common directory. Second, you add the _footer.gsp template to the layout using the <g:render template="/common/footer" /> tag. Third, you style the footer by adding a <div> section to the main layout using a style class that you defined in the main.css.

Now, you are going to take what you learned by creating the footer and start building the login/logout functionality.

Creating the Topbar

You create the topbar by adding a topbar (_topbar.gsp) template to the main layout. The topbar template is common and should be located in the grails-app/view/common directory. Listing 5-5 shows the content of the topbar template.

Listing 5-5. The Topbar Template (_topbar.gsp)

01 <div id="menu">

02 <nobr>

03 <g:if test="${session.user}">

04 <b>${session.user?.firstName} ${session.user?.lastName}</b> |

05 <g:link controller="user" action="logout">Logout</g:link>

06 </g:if>

07 <g:else>

08 <g:link controller="user" action="login">Login</g:link>

09 </g:else>

10 </nobr>

11 </div>

Listing 5-5 uses three Grails tags that you haven't seen yet: <g:if>,3 <g:else>,4 and <g:link>.5 The <g:if> and <g:else> tags work together to create "if-then-else" logic. The <g:link> tag creates a hypertext link (i.e., http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/user/logout). In lines 3–6, you check if the session has a User object. If the session has a User object, the user's name followed by a | and a Logout link is printed. Lines 7–9 shows the else condition of the if statement, which displays the Login link. Listing 5-6 shows how to add the topbar to the main layout.

Listing 5-6. Enhancing the Main Layout for the Topbar (main.gsp)

<html>

. . .

<body>

<div id="spinner" class="spinner" style="display: none;">

<img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',file:'spinner.gif')}"

alt="Spinner" />

</div>

<div id="topbar">

<g:render template="/common/topbar" />

</div>

<div class="logo">

<img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',file:'grails_logo.jpg')}"

alt="Grails" />

</div>

. . .

Now add the CSS fragments found in Listing 5-7 to main.css.

__________

Listing 5-7. The Topbar Styles

#topbar {

text-align:left;

width: 778px;

margin: 0px auto;

padding: 5px 0;

}

#topbar #menu {

float: right;

width: 240px;

text-align: right;

font-size: 10px;

}

Figure 5-4 shows the results.

Figure 5-4. Adding the topbar template

Notice that the Login/Logout link is located in the upper-right corner of the browser.

Adding More Look and Feel

Now you need to finish the transformation so that Collab-Todo has its own look and feel instead of appearing that it came right out of the box. Do this by adding the right sidebar, replacing the Grails header, and setting the default title. As noted earlier, Chapter 8 will use the right sidebar to display the user's buddies. Start off with some CSS styling by adding the CSS snippet in Listing 5-8 to the main style sheet (main.css).

Listing 5-8. CSS Styling

#header {

width: 778px;

background: #FFFFFF url(../images/header_background.gif) repeat-x;

height: 70px;

margin: 0px auto;

}

#header h1 {

font-family:Arial,sans-serif;

color: white;

padding: 20px 0 0 6px;

font-size:1.6em;

}

body {

margin: 0px;

padding: 0px;

text-align:center;

font-family: "Trebuchet MS",Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;

font-style: normal;

font-variant: normal;

font-weight: normal;

font-size: 13px;

line-height: normal;

font-size-adjust: none;

font-stretch: normal;

color: #333333;

}

#page {

width: 778px;

margin: 0px auto;

padding: 4px 0;

text-align:left;

}

#content {

float: left;

width: 560px;

color: #000;

}

#sidebar {

float: right;

width: 200px;

color: #000;

padding: 3px;

}

Note You can find header_background.gif in the project source.

Now, you need to take advantage of the CSS styling in the main layout (main.gsp), as shown in Listing 5-9.

Listing 5-9. Finishing the Layout (main.gsp)

01 <html>

02 <head>

03 <title><g:layoutTitle default="Collab Todo" />

04 </title>

05 <link rel="stylesheet"

06 href="${createLinkTo(dir:'css',file:'main.css')}" />

07 <link rel="shortcut icon"

08 href="${createLinkTo(dir:'images',file:'favicon.ico')}"

09 type="image/x-icon" />

10 <g:layoutHead />

11 <g:javascript library="application" />

12 </head>

13 <body>

14 <div id="page">

15 <div id="spinner" class="spinner" style="display: none;">

16 <img src="${createLinkTo(dir:'images', file:'spinner.gif')}"

17 alt="Spinner" />

18 </div>

19

20 <g:render template="/common/topbar" />

21

22 <div id="header">

23 <h1>Collab-Todo</h1>

24 </div>

25

26 <div id="content">

27 <g:layoutBody />

28 </div>

29

30 <div id="sidebar">

31 <g:render template="/common/buddies" />

32 </div>

33

34 <div id="footer">

35 <g:render template="/common/footer" />

36 </div>

37 </div>

38 </body>

39 </html>

Let's talk about the changes you made to the layout. Line 3 uses the <g:layoutTitle> tag. If the view being decorated doesn't have a title, then the default "Collab Todo" will be applied to the page. Line 14 adds a <div> that uses the page style. Together with the body style, the page style creates a container that's 778 pixels wide and centered on the page. Lines 22–24 replace the Grails header with the Collab-Todo header. If you look carefully at the CSS header style, you'll see that it defines a header image (header_background.gif). Lines 26 and 28 wrap the view's body with the content style. This means that pages decorated by main.gsp are inserted here. The content style creates a container 560 pixels wide and left-aligns it within the page container. Lines 30–32 wrap the buddies template with the sidebar style, which creates a container 200 pixels wide and right-aligns it within the page container.

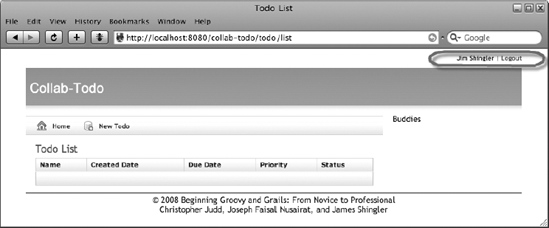

You can see the results of your work in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5. The completed layout

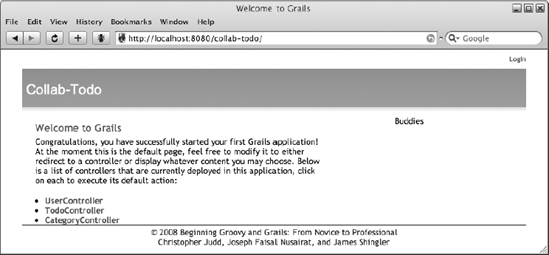

It's starting to look good; you have just one more thing to do. You won't use the default index page for long, but let's change "Welcome to Grails" and the body. You can find the HTML for this in web-app/index.gsp. Replace the contents of index.gsp with the contents found in Listing 5-10.

Listing 5-10. A New Index Page (index.gsp)

01 <html>

02 <head>

03 <title>Welcome to Collab-Todo</title>

04 <meta name="layout" content="main" />

05 </head>

06 <body>

07 <h1 style="margin-left:20px;">Welcome to Collab-Todo</h1>

08 <p style="margin-left:20px;width:80%">

09 Welcome to the Collab-Todo application. This application was built

10 as part of the Apress Book, "Beginning Groovy and Grails."

11 Functionally, the application is a collaborative "To-Do"

12 list that allows users and their buddies to jointly

13 manage "To-Do" tasks.</p><br />

14 <p style="margin-left:20px;width:80%">Building the Collab-Todo

15 application is used to walk the user through using Grails 1.0 to

16 build an application. Below is a list of controllers that are

17 currently deployed in this application. Click on each to execute

18 its default action:</p>

19 <br />

20 <div class="dialog" style="margin-left:20px;width:60%;">

21 <ul>

22 <g:each var="c" in="${grailsApplication.controllerClasses}">

23 <li class="controller"><a href="${c.logicalPropertyName}">

24 ${c.fullName}</a></li>

25 </g:each>

26 </ul>

27 </div>

28 </body>

29 </html>

A couple of items in the file deserve explanation. Lines 22–25 illustrate the usage of <g:each>, an iteration tag. In this case, it is iterating over a collection of all controller classes that are a part of the application to display the name of the controller class in a list.

Line 4 is an example of using layouts by convention. In this case, the layout metatag causes the "main" layout (main.gsp) to be applied to the page. You might recall that all layouts reside within the grails-app/views/layouts directory.

You have created the layout, and it's looking good. You can see the results of your work in Figure 5-6.

Figure 5-6. Layout results

Setting up the wireframe exposes you to layouts, templates, CSS, and a couple of Grails tags. Grails, like all modern web frameworks, supports tag libraries. The Grails tag library is similar to the JavaServer Pages Standard Tag Library (JSTL) and Struts tags. It contains tags for everything from conditional logic to rendering and layouts. The following section provides a quick overview of the Grails tags.6

Grails Tags

Part of Grails' strength in the view layer is its tag library. Grails has tags to address everything from conditional logic and iterating collections to displaying errors. This section provides an overview of the Grails tags.

Logical Tags

Logical tags allow you to build conditional "if-elseif-else" logic. Listing 5-5 demonstrated the use of the <g:if> and <else> tags in topbar.gsp. Table 5-2 contains an overview of the logical tags.

Table 5-2. Grails Logical Tags

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:if> |

Logical switch based upon a test expression |

<g:else> |

The else portion of an if statement |

<g:elseif> |

The else if portion of an if statement |

Iteration Tags

Iteration tags are used to iterate over collections or loop until a condition is false. The <g:each> tag was used in index.gsp in Listing 5-10. Table 5-3 contains an overview of the iteration tags.

Table 5-3. Grails Iteration Tags

__________

Assignment Tags

You use assignment tags to create and assign a value to a variable. Table 5-4 contains an overview of assignment tags.

Table 5-4. Grails Assignment Tags

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<def> (deprecated) |

Defines a variable to be used within the GSP page; use <set> instead |

<set> |

Sets the value of a variable used within the GSP page |

Linking Tags

Linking tags are used to create URLs. The <g:link> tag was used in topbar.gsp (shown in Listing 5-5), and <g:createLinkTo> was used as an expression in main.gsp (shown in Listing 5-9). Table 5-5 contains an overview of the linking tags.

Table 5-5. Grails Linking Tags

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:link> |

Creates an HTML link using supplied parameters |

<g:createLink> |

Creates a link that you can use within other tags |

<g:createLinkTo> |

Creates a link to a directory or file |

Ajax Tags

You use Ajax tags to build an Ajax-aware application. Chapter 8 uses some of these tags to enhance the user interface. Table 5-6 contains an overview of the Ajax tags.

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:remoteField> |

Creates a text field that invokes a link when changed |

<g:remoteFunction> |

Creates a remote function that is called on a DOM event |

<g:remoteLink> |

Creates a link that calls a remote function |

<g:formRemote> |

Creates a form tag that executes an Ajax call to serialize the form elements |

<g:javascript> |

Includes JavaScript libraries and scripts |

<g:submitToRemote> |

Creates a button that executes an Ajax call to serialize the form elements |

Form Tags

Form tags are used to create HTML forms. Table 5-7 contains an overview of form tags.

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:actionSubmit> |

Creates a submit buttoned |

<g:actionSubmitImage> |

Creates a submit button using an image |

<g:checkBox> |

Creates a check box |

<g:currencySelect> |

Creates a select field containing currencies |

<g:datePicker> |

Creates a configurable date picker for the day, month, year, hour, minute, and second |

<g:form> |

Creates a form |

<g:hiddenField> |

Creates a hidden field |

<g:localeSelect> |

Creates a select field containing locales |

<g:radio> |

Creates a radio button |

<g:radioGroup> |

Creates a radio button group |

<g:select> |

Creates a select/combo box field |

<g:textField> |

Creates a text field |

<g:textArea> |

Creates a text area field |

<g:timeZoneSelect> |

Creates a select field containing time zones |

UI Tags

You use UI tags to enhance the user interface. The only official UI Grails tag is the rich text editor, but several UI tags built by the Grails community are available as plug-ins. Table 5-8 contains an overview of the UI tag.

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:richTextEditor> |

Creates a rich text editor, which defaults to fckeditor |

Render and Layout Tags

Render and layout tags are used to create the layouts and render templates. As you might expect, several render and layout tags were used in main.gsp. Table 5-9 contains an overview of the render and layout tags.

Table 5-9. Grails Render and Layout Tags

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:applyLayout> |

Applies a layout to a body or template |

<g:encodeAs> |

Applies dynamic encoding to a block of HTML to bulk-encode the content |

<g:formatDate> |

Applies a SimpleDateFormat to a date |

<g:formatNumber> |

Applies a DecimalFormat to number |

<g:layoutHead> |

Displays a decorated page's header, which is used in layouts |

<g:layoutBody> |

Displays a decorated page's body, which is used in layouts |

<g:layoutTitle> |

Displays a decorated page's title, which is used in layouts |

<g:meta> |

Displays application metadata properties |

<g:render> |

Displays a model using a template |

<g:renderErrors> |

Displays errors |

<g:pageProperty> |

Displays a property from a decorated page |

<g:paginate> |

Displays Next/Previous buttons and breadcrumbs for large results |

<g:sortableColumn> |

Displays a sortable table column |

Validation Tags

Validation tags are used to display errors and messages. Table 5-10 contains an overview of the validation tags.

Table 5-10. Grails Validation Tags

| Tag Name | Tag Description |

<g:eachError> |

Iterates through errors |

<g:hasErrors> |

Checks if errors exist within the bean, model, or request |

<g:message> |

Displays a message |

<g:fieldValue> |

Displays the value of a field for a bean that has data binding |

Making the Topbar Functional

Now that you have the layout, let's make the topbar functional. You want the topbar to provide the user the ability to log in. Once the user has logged in, the topbar should display the username and provide the ability for the user to log out. When the user selects the Login link, he or she should be presented with a Login form.

Note The login functionality you are building initially is simply to identify who is using the system. It's not meant to provide a full, robust security system. Because the login you are constructing is temporary, adding authentication logic to all controller actions is out of scope at this time. In Chapter 7, you will add a fully functional security system.

The Login View

Creating the login view requires you to create a GSP in the appropriate directory. The GSP contains a form that has a single selection field of usernames and a submit button. When the user submits the selection, the form invokes the handleLogin action on the UserController. Figure 5-7 illustrates the login view.

Figure 5-7. The login view

Let's take a look at the Login link, <g:link controller="user" action="login">Login</g:link>. When the user selects the Login link, the login action on the UserController is invoked. We'll explain the login action in the next section.

Based upon convention, login.gsp should go in the grails-app/views/user directory. Listing 5-11 shows the contents of login.gsp.

Listing 5-11. The Login View (login.gsp)

01 <html>

02 <head>

03 <title>Login Page</title>

04 <meta name="layout" content="main" />

05 </head>

06 <body>

07 <div class="body">

08 <g:if test="${flash.message}">

09 <div class="message">

10 ${flash.message}

11 </div>

12 </g:if>

13 <p>

14 Welcome to Your ToDo List. Login below

15 </p>

16 <form action="handleLogin">

17

18 <span class='nameClear'><label for="login">

19 Sign In:

20 </label>

21 </span>

22 <g:select name='userName' from="${User.list()}"

23 optionKey="userName" optionValue="userName"></g:select>

24 <br />

25 <div class="buttons">

26 <span class="button"><g:actionSubmit value="Login" />

27 </span>

28 </div>

29 </form>

30 </div>

31 </body>

32 </html>

Let's review the form. Lines 1–5 define the title and determine that the page is decorated by the main layout. This means that main.gsp acts as a container for login.gsp. Take a look at line 26 in Listing 5-9. In this case, the body of login.gsp is inserted at the <g:layoutBody> tag. Remember that the main layout contains a default title, <g:layoutTitle default="Collab Todo" />. When login.gsp is decorated with the main layout, the title in login.gsp is used instead of the default that was defined in the layout.

Lines 6–31 define the body of the page. Lines 9–12 display flash messages, which we'll cover shortly in the "Flash and Flash Messages" section. Lines 16–29 create the form with a selection field. Line 16 specifies that when the form is submitted, the handleLogin action of the UserController is invoked. In lines 22–23, the Grails select tag creates an HTML selection element. The name attribute sets the selection name to userName (which in turn is passed to the login action). When evaluated, the form attribute results in a collection that Grails uses to create the options. optionKey and optionValue are special attributes used to create the HTML <option> element ID and the text display in the selection field. Lines 25–28 use the Grails <g:actionSubmit> tag to create a form submission button.

If you run the application and access the view right now, you'll get a 404 error. This is because the topbar links to the login view via the UserController login action, which hasn't been created yet.

The login Action

Currently, the UserController is set up with dynamic scaffolding. You will continue to use the dynamic scaffolding and add the login action to it. Listing 5-12 shows the updated version of the UserController class.

Listing 5-12. The login Action

class UserController {

def scaffold = User

def login = {}

}

A common best practice on the Web is to use actions as a redirection mechanism. By convention, Grails uses the name of the action to look up a GSP of the same name.

If you click on the Login link now, the login view will be displayed, and the User Name selection field will be blank. Recall from Listing 5-11 that you call User.list() to populate the selection with a collection of users. You haven't added any users yet, so the list is empty. Test the functionality of the form by creating two users. From the home page, select UserController ![]() New User. Now when you select Login, the User Name selection field is populated (see Figure 5-8).

New User. Now when you select Login, the User Name selection field is populated (see Figure 5-8).

Figure 5-8. A logged-in user

Next, you need to implement the login logic through the UserController handleLogin action.

Handling the Login and Logout Actions

You call the handleLogin action to log in a user. When you call the action, the Login form is passed the userName of the user to be signed in. Logging in is accomplished by adding the user object associated with the userName to the session. If the user cannot be found, an error message is created, and the user is redirected to the login view. In this particular example, there shouldn't be any way for the login to fail, but it is still good practice. You use the logout action to remove the user from the session, so he or she can log out. Listing 5-13 shows how you enhance the UserController.

Listing 5-13. Enhanced UserController

class UserController {

def scaffold = User

def login = {}

def handleLogin = {

def user = User.findByUserName(params.userName)

if (!user) {

flash.message = "User not found for userName: ${params.userName}"

redirect(action:'login')

}

session.user = user

redirect(controller:'todo')

}

def logout = {

if(session.user) {

session.user = null

redirect(action:'login')

}

}

}

Now, when the user logs in, he or she will be taken to the Todo List view when you log in, and the topbar will contain the user's first name, last name, and a Logout link. Line 8 in Listing 5-5 shows how selecting the Logout link invokes the UserController logout action.

Now that you have written code, you must make sure that you don't break it as you make other enhancements. That's next to impossible, but the next best thing is to steal an idea from Six Sigma,7 Poka Yoke.8 Poka Yoke is a Japanese word that means mistake proofing. The idea is to make mistakes so obvious that in effect, you prevent them. You accomplish this by creating tests. The next section will help you write tests for the code you just wrote.

Testing

Grails uses two popular testing frameworks—JUnit9 and Canoo10—to implement unit tests, integration tests, and functional tests. The purpose of testing is to verify that the application works as expected and to confirm that you haven't broken the application as you iterated over it. It is extremely valuable to have a good test framework.

In this section, you'll use JUnit to perform integration testing on the UserController, and you'll use Canoo to perform functional testing on the presentation. First, you will create a JUnit integration test for the UserController handleLogin and logout actions. Then you will create a test using the Canoo WebTest plug-in to functionally test the topbar.

Note Purists may suggest that you should have written the tests before you wrote the code. This has merit, but for the purposes of this book, it was more straightforward to show the code first. The important thing is that you have good tests that give you faith that the application works as intended.

__________

Integration Testing Using JUnit

In Chapter 4, when you ran the grails create-controller command to create the UserController, the command not only created the controller, but it also created an empty test in the test/integration test directory. Take a peek in the test/integration directory, and you'll see UserControllerTests.groovy. Listing 5-14 shows you the contents of the test when first generated.

Listing 5-14. UserControllerTests.groovy

class User ControllerTests extends GroovyTestCase

{

void testSomething() {

}

}Note If UserControllerTests.groovy doesn't exist for some reason, you can create it by executing grails create-integration-test and specifying UserController when prompted.

As you can see, a Grails test extends/inherits from GroovyTestCase,11

which in turn extends from junit.framework.TestCase.12 This means that Grails tests have all the features of JUnit and GroovyTestCase, including all the standard JUnit assert*, setUp, and tearDown methods and Groovy assert methods.

It is important to understand the distinction between integration and unit tests. A unit test is created with the grails create-unit-test command and results in a skeleton unit test in the tests/unit directory. One of the interesting things about Grails unit tests is that Grails dynamic methods, such as save, delete, and findBy*, are not available. Grails does this to help you understand the difference between unit tests and integration tests. The purpose of a unit test is to test the logic in a piece of code, not how the code and everything else around it (e.g., the database) interact—that is the purpose of integration tests. Right about now, you might be saying, "It's going to be awfully hard for me to test the logic in the code if I can't use dynamic methods." This is where Groovy's MockFor* and StubFor* methods come to your aid.

You're going to test the UserController handleLogin and logout actions using an integration test. Take a look at Listing 5-13, which contains the logic you want to test. The handleLogin action tries to find the user using the userName. If it finds the user, it adds the user object to the session, and the user is redirected to the Todo List view. If it doesn't find the user, it redirects the user to the login view. The logout action removes the user object from the session, and the user is redirected to the login view. You need two tests—one positive (a login with a valid user) and one negative (a login with an invalid user)—for handleLogin and one test for logout. Listing 5-15 contains the tests.

__________

Listing 5-15. UserController Integration Test

01 class UserControllerTests extends GroovyTestCase {

02

03 User user

04 UserController uc

05

06 void setUp() {

07 // Save a User

08 user = new User(userName:"User1", firstName:"User1FN", lastName:"User1LN")

09 user.save()

10

11 // Set up UserController

12 uc = new UserController()

13 }

14

15 void tearDown() {

16 user.delete()

17 }

18

19 /**

20 * Test the UserController.handleLogin action.

21 *

22 * If the login succeeds, it will put the user object into the session.

23 */

24 void testHandleLogin() {

25

26 // Setup controller parameters

27 uc.params.userName = user.userName

28

29 // Call the action

30 uc.handleLogin()

31

32 // If action functioned correctly, it put a user object

33 // into the session

34 def sessUser = uc.session.user

35 assert sessUser

36 assertEquals("Expected ids to match", user.id, sessUser.id)

37 // And the user was redirected to the Todo Page

38 assertEquals "/todo", uc.response.redirectedUrl

39 }

40

41 /**

42 * Test the UserController.handleLogin action.

43 *

44 * If the login fails, it will redirect to login and set a flash message.

45 */

46 void testHandleLoginInvalidUser() {

47 // Setup controller parameters

48 uc.params.userName = "INVALID_USER_NAME"

49

50 // Call the action

51 uc.handleLogin()

52 assertEquals "/user/login", uc.response.redirectedUrl

53 def message = uc.flash.message

54 assert message

55 assert message.startsWith("User not found")

56 }

57

58 /**

59 * Test the UserController.login action

60 *

61 * If the logout action succeeds, it will remove the user object from

62 * the session.

63 */

64 void testLogout() {

65 // make it look like user is logged in

66 uc.session.user = user

67

68 uc.logout()

69 def sessUser = uc.session.user

70 assertNull("Expected session user to be null", sessUser)

71 assertEquals "/user/login", uc.response.redirectedUrl

72 }

73 }

If you have used JUnit before, this will look familiar. Lines 3–17 contain the test setup and teardown functionality. The setup runs before each test, and the teardown runs after each test. The only interesting thing to point out here is that lines 9 and 16 use dynamic methods.

Lines 24–39 contain the handleLogin action positive test. The action takes userName as a parameter. Line 27 adds user.userName to the parameters to be passed to the action. Line 30 calls the handleLogin action using the parameters you just defined. Lines 34–36 validate that the action set the user into the session. If you look closely, you'll see that the test uses the Groovy assert and the JUnit assertEquals. In Groovy, assert considers null to be false. If the user wasn't put in the session, assert would fail. Line 38 looks in the UserController response to validate that the user was redirected to the Todo List view.

Lines 46–56 contain the handleLogin action negative test and use an invalid userName. As you might expect, lines 48–51 create an invalid username and call the action. Line 52 validates that the user is redirected to the proper view. Lines 53–55 validate that a flash message was generated to tell the user that he or she was not logged in. We'll cover flash messages in more detail shortly in the "Flash and Flash Messages" section.

Lines 64–71 contain the logout action test. Lines 66–68 manually add the user to the session and call the action. Lines 69 and 70 validate that the session doesn't contain a user object. Line 71 validates that the user is redirected to the login view.

Now for some fun. You run all the tests with the grails test-app command, and you run individual tests by appending the test name, as shown here:

grails test-app UserController

The command executes the UserControllerTest and produces the following output:

-------------------------------------------------------

Running 3 Integration Tests...

Running test UserControllerTests...

testHandleLogin...SUCCESS

testHandleLoginInvalidUser...SUCCESS

testLogout...SUCCESS

Integration Tests Completed in 2110ms

-------------------------------------------------------

[junitreport] Transform time: 719ms

Tests passed. View reports in <<PROJECT>>/test/reports

As you can see, everything passed. The test also generated a JUnit report under the test/reports directory. Figure 5-9 shows the JUnit HTML report.

Figure 5-9. JUnit report

Now you have some confidence that when you change code, you can make sure the handleLogin and logout actions function correctly. Now that you know that your actions are working individually, you need to create a test to verify that the topbar renders correctly when the user logs in.

Note As a side project, you could take a look at continuous integration (CI) tools13 and have the system execute your tests automatically. For more information, check out Martin Fowler's article.14

Functional Testing Using Canoo WebTest

If you recall, when the user first comes to the page, the topbar displays a link for the user to log in. Once the user has logged in, the topbar displays a link to log out. When you were testing manually, you had to add the user to the system, log in, and then check to make sure the topbar displayed the user's name. While this isn't a lot of work, do you really want to do this manually every single time you enhance the application? We hope the answer is no. Instead, you can create a suite of functional tests and let the computer do the regression testing of the presentation. All you have to do is kick it off or add it to your CI environment.

Grails has a Canoo WebTest plug-in, thanks to Dierk Koenig, founder and project manager of the Canoo WebTest plug-in. Canoo WebTest is a free open source tool that allows you to create functional tests. You start by installing the Canoo WebTest plug-in, then you generate and code a functional test for the user CRUD operations. Next, you create a functional test by hand to test the topbar functionality.

__________

14. Martin Fowler, "Continuous Integration," http://martinfowler.com/articles/continuousIntegration.html, 2006.

Install the WebTest plug-in by executing grails install-plugin webtest. Grails downloads the plug-in and installs it under the application's plugins directory. Next, generate a functional test by executing grails create-webtest. Grails first creates a webtest directory in the current project, then it creates a configuration file (webtest/conf/webtest.properties) and a test suite (webtest/tests/testsuite.groovy).

When prompted for a WebTest domain name, specify user. Grails uses WebTest templates to generate CRUD operation tests for the user object. Under normal circumstances, you shouldn't have to change the WebTest configuration, but in case you do, check out Table 5-11, which defines the contents of the configuration file.

Table 5-11. webtest.properties

| Name | Initial Value | Description |

webtest_host |

localhost |

The name of the host server |

webtest_port |

8080 |

The port number to start the test server on |

webtest_protocol |

http |

The protocol used to communicate with the server |

webtest_summary |

true |

Determines whether a summary report should be printed |

webtest_response |

true |

Determines whether a response should be saved to view from the report |

webtest_resultpath |

webtest/reports |

Determines where to put the reports |

webtest_resultfile |

WebTestResult.xml |

Specifies the name of the report results file |

webtest_haltonerror |

false |

Determines whether execution should be stopped if an error occurs |

webtest_errorproperty |

webTestError |

Specifies the name of the Ant property to set when an error occurs |

webtest_haltonfailure |

false |

Determines whether execution should be stopped if a failure occurs |

webtest_failureproperty |

webTestFailure |

Specifies the name of the Ant property to set when a failure occurs |

webtest_showhtmlparseroutput |

true |

Determines whether to show parsing warnings and errors in the terminal window |

The other generated file, testsuite.groovy, uses Ant fileScanner to load all classes in the webtest/tests directory that end with Test. It then executes them by calling their suite method. When you first start an application, the default behavior is probably good enough. As the application becomes more sophisticated, though, it may become necessary to have more control over the order in which the functional tests are executed. You can accomplish this by loading and executing the tests manually. Listing 5-16 shows an example.

Listing 5-16. Loading and Executing a Functional Test Manually

new MyTest(ant:ant, configMap:configMap).suite()

new MyOtherTest(ant:ant, configMap:configMap).suite()

Now that WebTest is installed, you can start creating the functional test. When Grails generates the WebTest, it does the best it can using a template. To make the test able to run, you need to add test values to the test.

Note Grails 0.6 featured a UI face-lift, which caused some challenges in the WebTest template. This may or may not have been fixed by the time you read this. In either case, tweaking the test is pretty straightforward.

Listing 5-17 contains a simple functional test that validates the usage of the user domain object through the presentation.

Listing 5-17. User WebTest

01 class UserTest extends grails.util.WebTest {

02

03 // Unlike unit tests, functional tests are often sequence dependent.

04 // Specify that sequence here.

05 void suite() {

06 testUserListNewDelete()

07 // add tests for more operations here

08 }

09

10 def testUserListNewDelete() {

11 webtest('User basic operations: view list, create new entry, view,

12 edit, delete, view'){

13 invoke(url:'user')

14 verifyText(text:'Home')

15

16 verifyListPage(0)

17

18 clickLink(label:'New User')

19 verifyText(text:'Create User')

20 clickButton(label:'Create')

21 verifyText(text:'Show User', description:'Detail page')

22 clickLink(label:'List', description:'Back to list view')

23

24 verifyListPage(1)

25

26 group(description:'edit the one element') {

27 clickLink(label:'Show', description:'go to detail view')

28 clickButton(label:'Edit')

29 verifyText(text:'Edit User')

30 clickButton(label:'Update')

31 verifyText(text:'Show User')

32 clickLink(label:'List', description:'Back to list view')

33 }

34

35 verifyListPage(1)

36

37 group(description:'delete the only element') {

38 clickLink(label:'Show', description:'go to detail view')

39 clickButton(label:'Delete')

40 verifyXPath(xpath:"//div[@class='message']",

41 text:/User.*deleted./, regex:true)

42 }

43

44 verifyListPage(0)

45

46 } }

47

48 String ROW_COUNT_XPATH = "count(//td[@class='actionButtons']/..)"

49

50 def verifyListPage(int count) {

51 ant.group(description:"verify User list view with $count row(s)"){

52 verifyText(text:'User List')

53 verifyXPath(xpath:ROW_COUNT_XPATH, text:count,

54 description:"$count row(s) of data expected")

55 } }

56 }

Use the grails run-webtest command to run the test and see what happens. When the test completes, it shows you the results in your default browser. Figure 5-10 is an example of what you'll see.

Figure 5-10. WebTest results

Looking at the results, you can see that the test failed. In the WebTests section of the report, you can see that zero tests passed (shown by the green check mark) and one test failed (shown by the red X). In the Steps section of the report, you can see that six steps passed (green check mark), one step failed(red X), and six steps were not executed (shown by the yellow o). Some steps failing can be expected, because Grails generates a skeleton implementation that you need to fill in. If you scroll down in the browser, you'll see more information about where it failed. The test failed in step 7, where the test verifies the text "Show User." Take a look at line 21 of Listing 5-17. The step failure means that it wasn't able to find the text "Show User" on the page. Most likely, something right before this didn't work as anticipated. Let's review the test.

Tip Because the meanings of WebTest commands are pretty clear, you can follow along and execute the same commands in a browser. It's almost like a checklist.

The core of the test starts on line 13. Lines 13–14 invoke the user URL, http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/user, and verify that the page contains the word "Home." Line 16 calls a method to verify that the page contains no items in the list.

Note If you take a look at the verifyListPage method, you'll see that it's using XPath expressions to count the number of entries in the list. Learn more about XPath on the W3Schools site.15

Lines 18–19 select the New User link and verify that the page contains the text "Create User." Line 20 selects the Create link. If you don't input anything in the User Name, First Name, or Last Name fields and you select the Create link, a flash message will appear telling you that the information is required. That's why line 21 failed. To fix the test, insert the code shown in Listing 5-18 right after line 20.

Listing 5-18. Setting Input Fields

// Set Inputs Start

setInputField(name:'userName', 'User1')

setInputField(name:'firstName', 'User1FN')

setInputField(name:'lastName', 'User1LN')

// Set Inputs End

This is how you insert values into the User Name, First Name, or Last Name fields using WebTest. Rerun the WebTest and take a look at the results.

Caution At the time of this writing, the template used to generate the WebTest wasn't integrated with the new look and feel of Grails. As a result, you may experience some additional errors. The errors are easier to resolve if you follow along with the test in your browser and then go to View ![]() View Source in the browser to see the resulting HTML. Doing so will give you an idea of how you can modify the test.

View Source in the browser to see the resulting HTML. Doing so will give you an idea of how you can modify the test.

Now you can build upon what you have learned to create a WebTest for the topbar functionality.

The grails create-webtest command assumes that you are creating a WebTest for a domain object. The topbar isn't a domain object, so you need to create the topbar test by hand. You can use the User WebTest (webtest/tests/UserTest.groovy) as a guide.

Create TopBarTest.groovy in the webtest/test directory. Make sure webtest/tests/TopBarTest extends grails.util.WebTest, and be sure to include the suite method. You need to follow these steps to test the topbar:

__________

15. W3Schools, "XPath Tutorial," http://www.w3schools.com/xpath/.

You could do all of the steps in one test method, but it makes more sense to divide them up into separate tests and use the suite method to control the sequence in which the tests are executed. A logical breakup would be testCreateNewUser, testLoginTopBarLogout, and testDeleteUser. Listing 5-19 contains an implementation of the WebTest to test the topbar.

Listing 5-19. WebTest to Test the Topbar

class TopBarTest extends grails.util.WebTest {

// Unlike unit tests, functional tests are often sequence dependent.

// Specify that sequence here.

void suite() {

testCreateNewUser()

testLoginTopBarLogout()

testDeleteUser()

}

/**

* Create the user that will be used in the login

*/

def testCreateNewUser() {

webtest('Test TopBar: create new user'){

invoke(url:'user')

verifyText(text:'Home')

clickLink(label:'New User')

verifyText(text:'Create User')

// Set Inputs Start

setInputField(name:'userName', 'User1')

setInputField(name:'firstName', 'User1FN')

setInputField(name:'lastName', 'User1LN')

// Set Inputs End

clickButton(label:'Create')

}

}

/**

* Login, look for name on TopBar, and log out

*/

def testLoginTopBarLogout() {

webtest('Test TopBar: login, verify topbar, logout'){

invoke(url:'user/login')

verifyText(text:'Login below')

setSelectField(name:'userName', value:'User1')

clickButton(label:'Login')

// after login should be on the todo view

verifyText(text:'Todo List')

// look for topbar information

verifyText(text:'User1FN')

verifyText(text:'User1LN')

verifyText(text:'Logout')

// logout

clickLink(label:'Logout')

// should be on the login view

verifyText(text:'Login below')

}

}

/**

* Clean up after ourselves, delete the user we added.

*/

def testDeleteUser() {

webtest('Test TopBar: delete user'){

invoke(url:'user')

verifyText(text:'Home')

// delete the first user.

clickElement(xpath:'//td/a',description:'go to detail view')

clickButton(label:'Delete')

// Handle the javascript popup

expectDialog(dialogType:'confirm', response:'true', description:

'Are you sure')

verifyText(text:'Home')

verifyText(text:'User List')

}

}

}

Listing 5-19 almost reads like a checklist of instructions that you would have to give someone to test it manually. Verify that the test works as expected by running the WebTest.

You now have a testing framework. You created integration tests on the handleLogin and logout actions of the UserController. You also created a functional test for the user domain object using the generated templates and a custom functional test for the topbar. The best source for help with WebTest is the Canoo WebTest manual,16 which contains some good examples. Translating the information in the manual to a Groovy implementation is straightforward.

Note Throughout the rest of the book, we will assume that you're maintaining tests and creating new tests for every enhancement you make. Periodically, we will revisit testing to focus on a particular aspect, tip, or gotcha that is related to the topic being covered.

Externalizing Strings

Like all modern Java web frameworks, Grails supports the concept of message bundles. It uses the <g:message> tag to look up a properties file for the text to be displayed. For example, say you're having a difficult time deciding if the topbar should say "Login" or "Sign In." You could externalize the string and just change the messages.properties file whenever you change your mind. Grails uses the message bundles to display errors. So, if you don't like the error message you're getting back, you can make it friendlier by modifying the message in the message bundle. The messages.properties file is located in the grails-app/i18n directory. Listing 5-20 shows the default contents of the messages.properties file.

Listing 5-20. messages.properties

default.doesnt.match.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}] does

not match the required pattern [{3}]

default.invalid.url.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}] is not

a valid URL

default.invalid.creditCard.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value[{2}]

is not a valid credit card number

default.invalid.email.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}] is

not a valid e-mail address

default.invalid.range.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}]

does not fall within the valid range from [{3}] to [{4}]

default.invalid.size.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}] does

not fall within the valid size range from [{3}] to [{4}]

default.invalid.max.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}]

exceeds maximum value [{3}]

default.invalid.min.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}] is

less than minimum value [{3}]

default.invalid.max.size.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value

[{2}] exceeds the maximum size of [{3}]

default.invalid.min.size.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value

[{2}] is less than the minimum size of [{3}]

default.invalid.validator.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value

[{2}] does not pass custom validation

default.not.inlist.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}] is

not contained within the list [{3}]

default.blank.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] cannot be blank

default.not.equal.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}]

cannot equal [{3}]

default.null.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] cannot be null

default.not.unique.message=Property [{0}] of class [{1}] with value [{2}]

must be unique

default.paginate.prev=Previous

default.paginate.next=Next

__________

Let's go back to the topbar WebTest example to demonstrate how to externalize strings. Take a look at Listing 5-5 to see the current topbar template. Change lines 5 and 8 to use the <g:message> tags. When completed, the topbar template should look something like what's shown in Listing 5-21.

Listing 5-21. Topbar Template with Messages

<div id="menu">

<nobr>

<g:if test="${session.user}">

<b>${session.user?.firstName} ${session.user?.lastName}</b> |

<g:link controller="logout"><g:message code="topbar.logout" /></g:link>

</g:if>

<g:else>

<g:link controller="login" action="auth">

<g:message code="topbar.login" /></g:link>

</g:else>

</nobr>

</div>

Now just add topbar.logout and topbar.login to the messages bundle:

topbar.login=Login

topbar.logout=Logout

You can easily change the text to display whatever you want without modifying the GSP. You still have to be careful, though. Depending upon how you modify the text associated with the message code, you may have to adjust the WebTest if it is looking for specific text. In a sophisticated application, you will have to make some decisions about functional testing. You need to ask yourself, "Should the functional test be run against a single locale or multiple locales?" If you decide on multiple locales, you will have to write a more robust functional test and pay particular attention to the usage of verifyText.

If you're an experienced web developer, you won't be surprised to find out that using the <g:message> tag also starts you on the path of internationalizing the application. The <g:message> tag is locale-aware; the i18n in the directory name to the messages.property file is a giveaway. By default, the tag uses the browser's locale to determine which message bundle to use.

Now that you understand message bundles, you can change the default messages displayed to something user friendly when errors occur.

Errors and Validation

In this section, you'll learn the difference between errors and flash messages, and you'll discover how to customize the messages.

If you try to submit a user form without entering a username, you will see error messages in action. When you violate a domain object's constraints, the red text that you see is an example of an error message. Figure 5-11 shows an example.

Figure 5-11. Error message

This screen shows the default error messages. As you saw previously in Listing 5-20, you can customize the message using the messages.properties file located in the grails-app/i18n directory. To get a better understanding of how this works, you need to switch the views and the controller from dynamic scaffolding to static scaffolding. Grails generates dynamic scaffolding on the fly when the application starts. If Grails can generate the code at runtime, it makes sense that it can generate the code at development time so you can see it. The generated code is called static scaffolding. Take a precaution against losing the existing implementation of the UserController by making a backup copy.

You can create the views for the User domain object by executing the command grails generate-views User. The command uses Grails templates to generate four new GSP pages in the grails-app/views/user directory: create.gsp, edit.gsp, list.gsp, and show.gsp. Now you need to create static scaffolding for the controller. You can create the controller for the User domain object by executing the command grails generate-controller User. Grails will detect that you already have an implementation of the controller and ask for permission to overwrite it. Give it permission; this is why you made a backup copy. After the UserController is generated, you need to copy the login, handleLogin, and logout actions from the backup to the newly generated controller. Listing 5-22 contains the contents of the save action.

Listing 5-22. The UserController.save Action

01 def save = {

02 def user = new User()

03 user.properties = params

04 if(user.save()) {

05 flash.message = "User ${user.id} created."

06 redirect(action:show,id:user.id)

07 }

08 else {

09 render(view:'create',model:[user:user])

10 }

11 }

The save action is called when the user clicks the Create button from the New User view. When line 4 is executed, Grails validates the user constraints before attempting to persist the user in the database. If validation succeeds, the user is redirected to the Show User view with the message "User ${user.id} created." If the save fails, the Create User view is rendered so that you can correct the validation errors without losing the previous input. When validation fails, Grails inserts an error message in the user object's metadata, and the user object is passed as a model object to the view. When the Create User view is rendered, it checks to see if there are any errors and displays them if appropriate. Listing 5-23 contains a short snippet that shows how to display the errors.

Listing 5-23. Display Errors

<g:hasErrors bean="${user}">

<div class="errors">

<g:renderErrors bean="${user}" as="list" />

</div>

</g:hasErrors>

As you can see, the generated GSP uses the <g:hasErrors> and <g:renderErrors> tags to detect and display the errors. The <g:hasErrors> tag uses the bean attribute to detect errors in the user object. If errors are detected, the body of the tag is evaluated, which results in the error being displayed by the <g:renderErrors> tag. The <g:renderErrors> tag iterates through the errors in the user object and displays them as a list. The display process knows that it is receiving an error code and error attributes. The tag looks up the error code in the message bundle, and the attributes are substituted in the message before it is displayed.

This technique works because the page is rendered from the controller. Take another look at line 6 in Listing 5-22. In the case of a redirect, the controller instructs the browser to go to the Show User view. The browser does this by calling the show action on the UserController. The controller then executes the show action and renders show.gsp. With all of this back and forth between the controller and the browser, can you imagine what it would take to make sure that all of the message information stays intact so it can be displayed by show.gsp? Well, this is where flash messages come to your rescue.

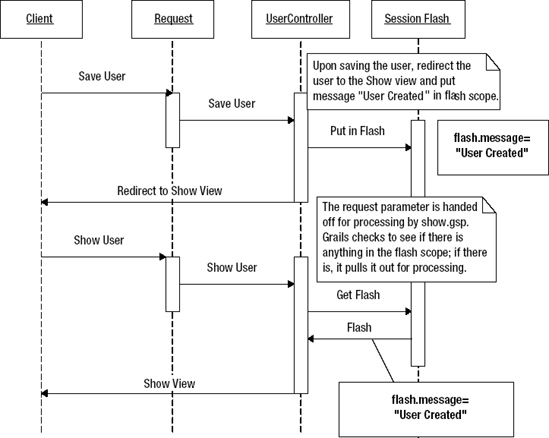

Flash and Flash Messages

What is flash scope and why do you need it? The short answer is that it is a technique implemented by Grails to make passing objects across redirects much easier. In other words, it addresses the problem described at the end of the previous section.

Figure 5-12 illustrates the problems associated with normal techniques of passing information from the controller to the view when a redirect is involved.

Figure 5-12. Redirect problem

On a redirect, if you try to use the request to carry the message to the Show view, the message gets lost when the browser receives the redirect. Another option would be to stick the message in the session and have the Show view pick it up from the session. However, in the Show view, you have to remember to delete the message from the session once it has been displayed; otherwise, the same message might be displayed on multiple views. The problem with this approach is that it depends upon you doing the right thing, and it's tedious.

This is where Grails comes to the rescue: it takes the last option and implements it for you and makes it part of the Grails framework. This is the flash scope. The flash scope works just like the other scopes17 (application, session, request, and page) by operating off a map of key/value pairs. It stores the information in the session and then removes it on the next request. Now you don't have to remember to delete the object in the flash scope. Figure 5-13 illustrates the concept of the flash scope.

Figure 5-13. Flash scope

__________

The Show view can access the flash scope objects—a message, in this case—and display them using the tags and techniques illustrated in Listing 5-24.

Listing 5-24. Access and Display a Flash Message

<g:if test="${flash.message}">

<div class="message">${flash.message}</div>

</g:if>

Grails isn't the only modern web framework that implements this technique. Ruby on Rails(RoR) developers should find this familiar.

Accessing a message from a flash scope looks pretty easy, but how do you put a message in flash? Listing 5-25 illustrates how the save action on the UserController puts a message into the flash scope.

Listing 5-25. Putting a Message in the Flash Scope

. . .

if(user.save()) {

flash.message = "User ${user.id} created."

redirect(action:show,id:user.id)

}

...

Grails implements a flash scope using a map. In this case, message is the key, and "User ${user.id} created." is the value.

What if you need to internationalize the code or want to change the message without editing the GSP? (Currently, the message is essentially hard-coded.) You can set it up to use message bundles just like errors do. Earlier in the chapter, you used the <g:message> tag to pull error messages from message bundles. You can do the same thing for flash messages using a couple of attributes. Listing 5-26 illustrates how to use the <g:message> tag to display flash messages.

Listing 5-26. Using the <g:message> Tag to Display a Flash Message

<g:message code="${flash.message}" args="${flash.args}"

default="${flash.defaultMsg}"/>

Listing 5-27 illustrates the enhancements to the save action to set the values that the message tag will use.

Listing 5-27. Setting Values in a Flash Scope for Use by the <g:message> Tag

...

if(user.save()) {

flash.message = "user.saved.message"

flash.args = [user.firstName, user.lastName]

flash.defaultMsg = "User Saved"

redirect(action:show,id:user.id)

}

...

The flash.message property is the message code to be looked up in the message bundle, flash.args are the arguments to be substituted into the message, and flash.defaultMsg is a default message to display in the event of a problem.

Only one thing left to do: create an entry in the message bundle with the user.saved.message code and whatever you would like the text to be. See Listing 5-28 for an example.

Listing 5-28. Flash Message Code Example

user.saved.message=User: {0} {1} was saved

The results should look something like what's shown in Figure 5-14.

Figure 5-14. Customized flash message

Note Any action can call or redirect to the Show view. At this point, you may be wondering what happens if flash.args and flash.defaultMsg aren't set. The <g:message> tag is pretty smart; it does the logical thing. It displays the contents of flash.message. To see it in action, update an existing user and take a look at the message displayed.

Now that you know about the flash scope and messages, you can create customized and internationalized application messages with a minimal investment.

You have learned quite a bit about Grails user interfaces and have established the basic look and feel. Now it's time to start implementing some logic and control.

Controlling the Application

The application has the ability to create users, log in as a user, log out, and even create categories and to-do items. However, if you spend some time playing around with multiple users, you'll discover that users can modify and delete each other's information. That's not good.

Controlling Users

In this section, you will modify the controllers to prevent user 1 from accidentally changing user 2's information, and you'll add a simple audit log using an interceptor. Let's start with the user information. It is not a problem for users to see each other's user details, but they shouldn't be able to change them or delete another user.

Let's analyze the problem for a second. You might take a UI-centric approach, and in the GSP, just don't show the link to edit the user unless the ID of the current user is the same as the ID being displayed. If everyone in the world were trustworthy, that might work, but it has some serious flaws.18 For example, a large system might have multiple places that implement the logic you're trying to guard against. A controller/action-centric approach is a better answer and probably sufficient for a simple application. Centralizing the authorization check in the controller/action has the benefit of guarding the update logic no matter how it is called.

Note The UI approach might still be worthwhile from a user experience perspective, but you should never use it as a replacement for the more centralized controller/action approach. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive; you can use them together.

__________

18. You will learn more about security in Chapter 7.

Listing 5-29 contains the default implementation of the edit action.

Listing 5-29. The edit Action

def edit = {

def user = User.get( params.id )

if(!user) {

flash.message = "User not found with id ${params.id}"

redirect(action:list)

}

else {

return [ user : user ]

}

}

As you can see, the edit action retrieves the user to be edited based upon params.id. In this case, params.id is the ID of the user to be edited. If the user ID to be edited isn't the same as the currently logged-in user, then the user should be returned to the User List view and view a message that states, "You can only edit yourself." You can accomplish this by changing the implementation of the edit action to match Listing 5-30. Don't forget that when a user logs into the application, that user is put into the session.

Listing 5-30. The edit Action with User Check

def edit = {

if (session.user.id != params.id) {

flash.message = "You can only edit yourself"

redirect(action:list)

return

}

def user = User.get( params.id )

if(!user) {

flash.message = "User not found with id ${params.id}"

redirect(action:list)

}

else {

return [ user : user ]

}

}

Make sure to include the return statement. Failure to do so will result in the action continuing to process after the browser has been instructed to go to a different action. As you can see, you use flash.message to make the error message available to the List view. You should apply the same logic to the update and delete actions to prevent users from updating or deleting a record other than their own. Let's explore this action a little deeper.

params is a mutable map of request parameters. The fact that it is mutable allows you to add or modify request parameters. You can even pass them to other actions. You use the dot dereference operator to access the value for the key id. This works well and is the preferred method for accessing a map when the key is not an invalid identifier—in other words, when it doesn't have invalid characters such as dot or /. For special cases, you can use the subscript operator to access params. Listing 5-31 illustrates using the subscript operator. This technique is also useful when the key is not known until runtime (i.e., passed in as a variable).

Listing 5-31. Accessing Request Parameters Using the Subscript Operator

def user = User.get(params['id'])

This brings up an additional point of interest. Because params is a request parameter map, you have been accessing request parameters in the controller actions. You might be wondering, "How did the parameters get passed into the action?" Go to the User List view and select a user to show. Now take a close look at your browser URL, which should look something like the screen shown in Figure 5-15. The callouts aren't part of the URL; they are used to identify the different parts of the URL.

Figure 5-15. The URL

Remember that not everyone in the world is trustworthy. This is why it isn't good enough to just not show the link on the view. A mischievous person could type the URL directly into the browser and bypass the view. Figure 5-16 illustrates passing additional request parameters on the URL.

Figure 5-16. Additional request parameters

Another interesting point in Listing 5-30 is the last return statement. In Grails, actions can do many things, one of which is returning a model that is used by the view to display information. A model is a map of key/value pairs. The return [user : user] statement returns a Groovy map.19 This can be a little confusing. Grails leverages Groovy's ability to create a map using the [:] notation. The entry before the : is the key, and the entry after the : is the value (i.e., [key:value]).

Note Groovy provides an implicit return. The value returned is the value of the last statement in the action/closure. For example, take a look at the show action on the UserController.

Listing 5-32 illustrates how show.gsp uses the information in the User object to display the user's name.

Listing 5-32. Using the User Object in a View

<tr class="prop">

<td valign="top" class="name">User Name:</td>

<td valign="top" class="value">${user.userName}</td>

</tr>

${user.userName} is accessing the model map by the user key and then accessing the userName property from the value object. In this case, the value object is the User domain object. You can think of this as ${modelMapKey.modelMapValue}.

Before you move on with the application, let's take a look at some other actions in the UserController. Listing 5-33 shows the implementation of the save action.

__________

Listing 5-33. The UserController save Action

01 def save = {

02 def user = new User()

03 user.properties = params

04 if(user.save()) {

05 flash.message = "user.saved.message"

06 flash.args = [ user.firstName, user.lastName]

07 flash.defaultMsg = "User Saved"

08 redirect(action:show,id:user.id)

09 }

10 else {

11 render(view:'create',model:[user:user])

12 }

13 }

Line 3 demonstrates a powerful feature of Grails called data binding. The save action is typically called from the Create view. Taking a quick look at the user Create view will help you understand how the save action works. The view is used to create users. In the process of creating users, the view supports creating userName, firstName, and lastName using a form component. When the form is submitted, userName, firstName, and lastName are put in the parameters map. Line 3 sets the domain properties from the request parameters. In Chapter 6, you will learn more about domain objects and properties; this is just a preview.

Data binding is handy and saves lots of code. If you're an experienced web developer, go take a look at one of your existing applications to see how much effort it took to assign form data to domain objects. As an aside, you can also use an overridden constructor to assign the values (e.g.,def user = new User(params)).

After assigning the domain object properties, the action attempts to save the object. In the process of saving the object, it is validated. If the object passes validation and the save succeeds, the user is redirected to the Show view, and the user.saved.message message is displayed. If the save fails, the Create view is redisplayed, and the validation errors are displayed.

Line 11 demonstrates using the render method to display the Create view and pass the failed user object to the model. You may be asking, "Why would it pass the user back?" The view uses the user object to repopulate the form so that the user can correct mistakes. That's great, and it saves a good deal of development effort too. But how does the view know what failed in validation? We'll cover this more in Chapter 6, but the short answer is that Grails adds an error collection to the domain object. The view retrieves the error messages from the domain object.

Let's review some of what you have learned while restricting modification of user information. You learned how to introduce logic into the edit,update, and delete actions to prevent users from modifying information unless the users themselves are making the change. You explored request parameters and the Grails URL when examining why the check must be in the controller action. While you were looking at the UserController, you also took a quick look at how information is passed back to the view in the form of a model and how parameters are set into domain objects using data binding. You also had a preview into Chapter 6's discussion of domain object validation, and you learned that when validation fails, the view can ask the domain object for the error messages. With this information, you're now ready to further enhance the application by controlling what category and to-do information is displayed.

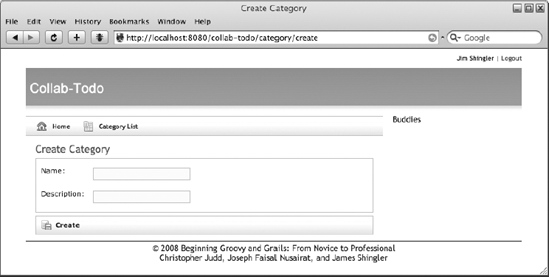

Controlling Categories

When the user navigates to the Category List view, all of the categories are displayed, including other users' categories. When a user is maintaining categories, having other users' categories in the list is just a distraction and provides no value. The goal is to take what you just learned about controller actions and apply it to the Category controller. The first step is to generate the category views and controller by executing the commands grails generate-views Category and grails generate-controller Category. The second task is to restrict the categories displayed in the List view by restricting the categories returned from the list action. Listing 5-34 contains the contents of the list action before you enhance it.

Listing 5-34. The list Action

01 def list = {

02 if(!params.max)params.max = 10

03 [ categoryList: Category.list( params ) ]

04 }

Line 2 checks to see if the params map contains a key named max. If it doesn't, the code creates a new key/value pair in params, called max, with a value of 10. The dynamic method, list, uses the max parameter to limit the number of categories returned. Line 3 calls the dynamic method list on the category domain object and returns the results to the List view. You will learn more about dynamic methods20 in Chapter 6. You need to make the changes illustrated in Listing 5-35 to restrict categories to the currently logged-in user.

__________

Listing 5-35. Restricting the list Action

01 def list = {

02 if(!params.max)params.max = 10

03 def user = User.get(session.user.id)

04 [ categoryList: Category.findAllByUser(user, params) ]

05 }

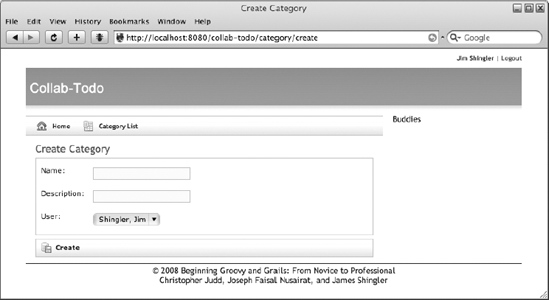

Line 3 retrieves the current user based upon the user information in the session. Line 4 finds all the categories for the user retrieved on line 3. Line 4 is an example of using a dynamic finder method. You will learn about dynamic finder methods in Chapter 6. When that application is run, you will see that the display now restricts the List view to the currently logged-in user. Figure 5-17 illustrates the Create view.

Figure 5-17. Create view

Now that the category views are restricted to the currently logged-in user, having the user displayed in any of the views is redundant. Removing the user selection component is a two-step process. First, you need to remove it from the views (grails-app/views/category/*.gsp), and default the user to the currently signed-on user when the save and update actions are called. This process is straightforward, and I'll leave it up to you. Let's focus on the second step, in which you default the user in the save and update actions. Listing 5-36 highlights the enhancements to the save and update actions to enable defaulting the users.

Listing 5-36. Defaulting the User

def update = {

def category = Category.get( params.id )

if(session.user.id != category.user.id) {

flash.message = "You can only delete your own categories"

redirect(action:list)

return

}

def user = User.get(session.user.id);

if(category) {

category.properties = params

category.user = user

if(category.save()) {

flash.message = "Category ${params.id} updated."

redirect(action:show,id:category.id)

}

. . .

def save = {

def category = new Category()

category.properties = params

def user = User.get(session.user.id);

category.user = user

if(category.save()) {

flash.message = "Category ${category.id} created."

redirect(action:show,id:category.id)

}

else {

render(view:'create',model:[category:category])

}

}

Take a look at flash.message. This is a Groovy String, or GString.21 The ${} allows you to insert an expression into a string. In this case, the value of category.id is inserted into the string. Figure 5-18 shows the cleaned-up Create view.

__________

Figure 5-18. Cleaned-up Create view