TWO

Stories of Organizing

Question to a consultant:

“So—are you helping them get organized?”

“No—I am helping them get disorganized.”

Organizing Like a Cow

Courtesy of Socket Software

This bedtime story may seem to be over the moon. It is not!

To pick up on an ad that appeared some years ago for a major software company, the drawing above is not a cow. It’s a chart of a cow—its parts. In a healthy cow, these parts don’t even know that they are parts; they just work together harmoniously. So, would you like your organization to work like a chart? Or like a cow?

This is a serious question. Ponder it. Cows have no trouble working like cows. Nor, for that matter, does each of us, physiologically at least. So why do we have so much trouble working together socially? Are we that confused about organizing, for example all this obsession with charts?

I discuss this cow in our International Masters Program for Managers (IMPM). One time, in the module we hold in India, while crossing the bustling streets of Bangalore the managers experienced another story about cows. As recounted to me by Dora Koop, a colleague at McGill: “The first day we were told that when we crossed the street in India we had to ‘walk like a cow.’ The whole group had to stay together, and we were warned not to do anything unexpected. So we just moved slowly across the street, and the traffic went around us. Throughout the whole program, people used this cow metaphor [recalling the other one too, about working like a cow].”

Picture this: a mass of people, all as one, advancing steadily and cooperatively through what looks like chaos. Now imagine the people of your organization advancing steadily and cooperatively through what looks like its chaos.

In walking like a cow, we have an answer to working like a cow: it’s about walking and working together. Beyond the sacred cow of leadership lies the idea of communityship, a word I coined to put leadership in its place.14

Communityship beyond Leadership

Laura and Tomas, two of my grandchildren; Teddy, their dog; and Ted, a beaver sculpture.15 (Photo by Susan Mintzberg)

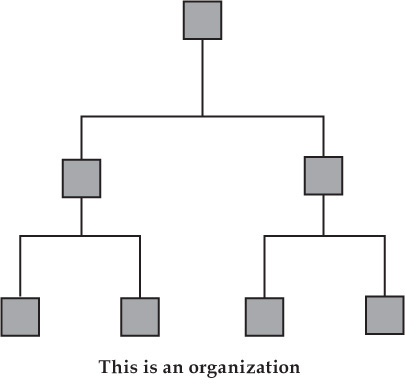

Say “organization” and we see leadership. That’s why those charts are so ubiquitous. They tell us who is supposed to lead whom but not who does what, how, and with whom. Why are we so fixated on formal authority? Have a look at the top figure on the next page to see an organization. Then look at the bottom figure to see a reorganization.

Did you notice the difference? True, a few names were changed in a few boxes, but the chart—how we see the organization—remains the same. Is there no more to organizing than bossing?

Do you know why reorganizing is so popular? Because it’s so easy. Shuffle people on paper and the world is transformed—on that paper at least. Imagine instead if people were shuffled around offices to make new connections.

Say “leadership” and we see an individual—even if that individual is determined to “empower” everyone else. (Is that necessary?) Often, however, it’s about a great white knight riding in on a great white horse to save everyone (even when headed straight into a black hole). But if one person is the leader, everyone else must be a follower. Do we really want a world of followers?

Think of the established organizations that you admire most. I’ll bet that beyond any leadership exists a powerful sense of communityship. Effective organizations are communities of human beings, not collections of Human Resources.

How can you recognize communityship in an organization? That’s easy: you feel the energy in the place, the commitment of its people, and their collective interest in what they do. They don’t have to be formally empowered because they are naturally engaged. They respect the organization because it respects them. There is no fear of being fired because some “leader” hasn’t made the anticipated numbers on some bottom line.

Sure we need leadership, especially to enable and establish communityship in new organizations, as well as to help sustain it in established ones. What we don’t need is an obsession with leadership—of some individual being singled out from the rest, as if he or she were the be-all and end-all of organizing (and is paid accordingly). So here’s to just enough leadership, embedded in communityship.

Networks Are Not Communities

If you want to understand the difference between a network and a community, ask your Facebook friends to help paint your house. Networks connect; communities care.

Social media certainly connects us to whoever is on the other end of the line and thus extends our social networks in remarkable ways. But this can come at the expense of our personal relationships. Many of us are so busy texting and tweeting that we barely have time for meeting and musing. Where are we supposed to get the meaning? One important answer: through face-to-face contact in the communities where we work and live.

Marshall McLuhan wrote famously about the “global village” created by the new information technologies. But what kind of village is this? In the traditional village, you connected with your neighbors at the local market. It was the heart and soul of community. When a neighbor’s barn burned down, you may have pitched in to help rebuild it.

Markets then (photo courtesy of Journal Grande Bahia [JGB], Brazil)

In today’s global village, the most prominent market is the soulless stock market. At home in this village, when you click on some keyboard, the message could be going to some “friend” you’ve never met. The relationship remains untouched, and untouchable, like those fantasy-ridden love affairs on the internet.16

In his New York Times column, Thomas Friedman quoted an Egyptian friend about the 2011 Arab Spring protest movement in Cairo: “Facebook really helped people to communicate, but not to collaborate.” Friedman added that “at their worst, [social media] can become addictive substitutes for real action.”17 That is why, while mass movements can raise awareness of the need for social renewal, it is social initiatives, usually developed by small groups in local communities, that start much of the renewing.

Markets now (photo courtesy of Newcam Services, Inc., NYSE)

Transformation from the Top? Or Engagement on the Ground?

The company has a new chief, with 100 days to show the stock market some quick wins. Hurry up and reinvent the company.

Transformation from the top

But where to begin? That’s easy: with transformation, from the “top.” Louis XIV said, “L’état, c’est moi!” Today’s corporate CEO says, “The enterprise, that’s me!”

John Kotter has written the widespread word on transformation, at Harvard Business School, where “62 per cent of cases feature heroic managers acting alone.”18 Here is the Kotter model, in eight steps:19

1. Establish a sense of urgency.

2. Form a powerful guiding coalition.

3. Create a vision.

4. Communicate the vision.

5. Empower others to act on the vision.

6. Plan for and create short-term wins.

7. Consolidate improvements and produce still more change.

8. Institutionalize new approaches.

Please read these again, asking yourself every step of the way, Who does each? The chief and nothing but the chief, so help you Harvard. Everyone else is expected to obediently pursue the chief’s vision—one leader, many followers. Indeed, the article states that “powerful individuals who resist the change effort” must be removed. What if they have good reason to resist? Can there be no debate, no discussion? Must the twenty-first-century corporation ape the court of Louis XIV?

Consider the steps. “Establish a sense of urgency”—to barrel ahead: because the wolves of Wall Street are baying at the door? A “guiding coalition,” with senior managers always at the core, will “create a vision”: out of the thin air at the top? No wonder so many companies have copycat strategies they call visions.

Then “communicate the vision” to all those followers on the ground—and, to continue with the clichés, by “empowering [them] to act on the vision,” as if people hired to do a job need the chief’s permission to do it.

And keep those “short-term wins” coming with “still more change”—more and more change. Where is continuity in all of this, bearing in mind that change without continuity is anarchy? Finally, don’t forget to “institutionalize” it all because the vision was fixed in step 3.

Engagement on the ground

If change is so good, how about changing the process of change for a change? How about recognizing “top” as a metaphor that can distort behavior, so that strategies can be allowed to form amid the clutter of making products and serving customers?

Here is one pointed example, about how IKEA came to sell its furniture unassembled, so that we customers can take it home in our cars, saving ourselves and the company much money. The inspiration for this powerful guiding vision, which transformed the company and the furniture business, started with a worker. “Exploration of flat packaging begins when one of the first IKEA co-workers removes the legs of the LÖVET table so that it will fit into a car and avoid damage during transit.”20

The site does not say it, but someone had to come up with the insight that if we have to take the legs off, maybe our customers have to do so, too. This could have been the worker, or a manager, perhaps even the CEO, since serious entrepreneurs spend much time on the ground. But if not the CEO, this insight had to be conveyed to him so that he could sprinkle some holy water on it. And this suggests that IKEA was an organization of open communication, not one fixated on tops and bottoms, between which so many ideas get lost. In other words, this kind of change has more to do with open culture than transformation.

So instead of a model of top-down transformation, how about a process of grounded engagement?

Here are a few basics of grounded engagement—not steps, mind you, nonlinear, no order, just a composite, like change itself.

Anyone can come up with the idea that becomes the vision. Taking the legs off a table may not have been a big deal, but it launched a very big deal.

Communication is open so that such ideas get around. With no top and bottom, people connect in flexible networks. They listen, all around—even to resisters—for the sake of progress.

Strategies thus form by learning, not planning. They need not be immaculately conceived. Competitive analyses can help, but this is fundamentally about engaged people learning their collective way to unexpected strategies.21

Of course, there is the need to pull diverse insights together, which is usually overseen by a management that’s on top of what’s going on.

One final point: Organizations do sometimes need transformation, for example when the shock of a sudden shift in markets puts them in danger. But too many organizations turn to the fix of transformation because of a spell of disconnection. In contrast, those that stay connected need fewer fixes. So, managers, pundits, and professors had better be careful about transformation and instead pay more attention to communityship.

Species of Organizations

There are species of organizations just as there are species of mammals. Don’t mix them up. A bear is not a beaver: one winters in caves, the other in wooden structures they build for themselves. Likewise, a hospital is not a factory any more than a film company is a nuclear reactor.22

Are all birds alike?

This may seem obvious, yet we are masters of mixing up the different species of organizations. Our vocabulary for understanding them is really quite primitive. We use the word organization the way biologists use the word mammal, except that they have labels for the different species and we do not.

Imagine two biologists who meet to discuss where mammals should spend the winter. “In a cave,” says the one who studies bears. “Are you kidding?” says the other, who studies beavers: “Their predators will enter and eat them. They need to build protective lodges out of the trees they cut down,” to which comes the reply, “Now you’re the one who’s kidding!” They talk past each other, just like the manager of a hospital who tries to explain to a consultant that it is not a factory.

All dogs are different.

Some years ago I set out to address this problem in a book called The Structuring of Organizations. It has been my most successful book, but not successful enough because the way we discuss organizations remains primitive. So let me try again here, offering my framework of four basic species of organizations.

The programmed machine Many organizations function like well-oiled machines. They are about efficiency, namely getting the greatest numerical bang for the numerical buck. Accordingly, everything is measured and programmed to the nth degree—for example, how many seconds before a McDonald’s cook has to turn over a hamburger patty. This makes it easy to train the workers but not to keep those workers engaged: their jobs can be boring and the controls stifling. The programmed machine is great at what it does well—you want your wake-up call in the hotel at 8:00, and that’s when it comes!

But don’t expect innovation. Will you be amused to lift the pillow in your hotel room and have a jack-in-the-box jump up and say, “Surprise!”? But that is what you want from your advertising agency.

The professional assemblage This species is programmed too but in an entirely different way. It is about proficiency more than efficiency. In hospitals, accounting firms, and many engineering offices, the critical work is highly skilled—it requires years of training—even though much of it can be surprisingly routine. To appreciate this, imagine being wheeled into an operating room as a nurse says, “You have nothing to worry about: this is a really creative surgeon!”

In this species even the professionals who seem to be working in teams are usually working largely on their own; their training has taught them exactly what to expect from one another. A doctoral student of mine observed a five-hour open heart operation during which the surgeon and the anesthesiologist never talked to each other.

The personal enterprise Here one person dominates. It’s all about central directing. Think of entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs at Apple or Muhammad Yunus, who established microfinancing at the Grameen Bank as a social enterprise. Sometimes older organizations in crisis take on this form, too, to centralize power so that one person can deal with it. Most small organizations—your corner grocery store, for example—tend to be focused on one person too, usually the owner, simply for convenience. And then there are those totalitarian political regimes, with one autocrat in command.

When the head of a personal enterprise says, “Jump!” the response tends to be: “How high, sir?” When the executive director of a hospital says, “Jump,” the doctors ask, “Why?”

The project pioneer This fourth species is different again. Here the work is also highly skilled, but the experts have to work in teams to combine their efforts for the sake of innovation. Think about film companies, advertising agencies, and research laboratories—all of which organize around projects to create novel outputs: a film, an ad campaign, a new product. To understand this species, you have to appreciate that it achieves its effectiveness by being inefficient. Without some slack, innovation dies.

Each of these species requires its own kind of structure and its own style of managing. Moreover, they don’t just have different cultures; they are different cultures. Walk into various ones and you can’t miss the differences.

Yet the vast majority of the popular literature on organizations is about the programmed machines—without ever recognizing that fact. We read incessantly about the need for tighter controls and more central planning, to measure everything in sight, to become more “efficient.” Or else about how to compensate for the worst effects of this species by, as was once put so eloquently, bringing in “the maintenance crew for the human machinery.”23

I have been discussing these species as if all organizations are one or the other. Some do come remarkably close—for example, a programmed McDonald’s or a personal Trump enterprise. Yet a machinelike mass producer can have a project department for product innovation, just as a professional hospital can have a machinelike cafeteria, not to mention a creative surgical team when something does go wrong in that operating room. And then there are the hybrids—for example, a pharmaceutical company that is project in its research, professional in its development, and machinelike in its production.

Does this negate the framework? Quite the contrary: it suggests that we can use this vocabulary to talk more sensibly about all the different things that go on in organizations.

Why Do We Say “Top Management” but never “bottom management”?

You no doubt say “Top Management” in your organization and “middle management” too. So why don’t you say “bottom management”? After all, the managers there know that if one manager is on top and others are in the middle, they must be at the bottom. What this actually tells us is that “top” is just a metaphor—and a silly one at that. On top of what?

1. On top of the chart, to be sure (see it below). But take that chart off the wall and put it on a table to see the top for what it is: no higher than anything else.

2. On top of the salary scale too. But how can we call anyone a “leader” who accepts being paid several hundred times more than the organization’s regular workers?

3. Usually on top of the building too. From up there, however, top managers can see everything in general and nothing in particular. Bear in mind too that the bottommost of bottom managers in Denver sit thousands of feet higher than the topmost of top managers in New York.

4. Well then, how about on top of what’s going on in the organization? Certainly not. Seeing yourself on top of your organization is no way to keep on top of what’s going on in it. Say “top” and we picture someone hovering over the place, as if on some sort of cloud, removed from everyone on the ground.

So how about this: get rid of Top Management (the term, I mean) and replace it with central management.

In the outer circle, all around the organization, can be placed the managers who face out to the world, in closest touch with the customers, the products, and the services. Let’s call them operating managers. And between them and the central managers are the connecting managers. They still translate from the center to the operations, but they also carry the best ideas of the operations to the center. This can be a lot more effective than having to keep rolling their ideas up some hill like Sisyphus.

In this depiction, instead of treating middle managers as burdens on the organization—to be “downsized” at the first opportunity—these connecting managers can be seen as key to constructive change. In fact, the best of them appreciate the big picture while being grounded enough to help develop it.

But there is a problem with this view, too. Picturing one person in the center can “centralize” the organization: everything may revolve around that individual. This might be fine for a personal enterprise, but how about a project pioneer? Why not, then, picture it as a network, or web, of people interacting every which way?

But where to put the manager of such a web? That’s easy: everywhere—namely out of the office, off some upper floor, and into the places where the organization lives. Do this, and the network can function as a community.

To conclude, if you would like to do some worthwhile downsizing in your organization, begin with the bloated vocabulary of “Top Management.” Stop using it. That way you can look all around, instead of up and down, to appreciate who can best get each job done.

Enough of Silos? How about Slabs?

We all know about silos—those vertical cylinders that keep people horizontally apart from each other in organizations, makers from sellers, doctors from nurses. In fact, we have probably all heard more than enough about silos.

Well, then, how about slabs, those horizontal barriers to the free flow of information.24 We all know them too, if not by that name. In one Czech company, people talked about the seven executives on the top floor as some kind of inner sanctum, isolated from everyone else. And women have long complained about the “glass ceilings” that keep them from advancing up the hierarchy.

Once I did a workshop on these silos and slabs with the senior managers of a bank. They concluded that silos were the problem, not slabs. “You might want to check that out with some people on a slab or two below you,” I suggested.

We may need silos for the sake of specialization in our organizations, but we don’t need impenetrable walls. To use another metaphor, it’s not seamlessness we need in our organizations but good seams: tailored connections between the silos. The same can be said about the slabs, too, across the different levels of authority. Must the CEO, COO, CFO, and CLO all sit above, together?

A cardinal rule of management development programs is that different levels of managers must never be mixed. Keep the CEOs with the CEOs, middle managers with middle managers, and so on. Why? For the sake of status? Many C-suite executives already spend too much time with their peers. What they really need is to tap into the thinking of other kinds of managers. How about a little mingling, all you Cs? Get an earful from someone in another organization who can tell you what you’ll never hear from your own people.

Or how about coming down from those inner sanctums to put your desk next to people who have a different perspective? Kao, a Japanese manufacturer of personal care and other products, became famous for running its meetings in open spaces and allowing anyone going by to join: a foreman at the executive committee, an executive at a factory meeting. Semco, a Brazilian company, reported keeping two seats at its board of directors meetings open for workers. It’s easy to bust the slabs when you realize that they are mere figments of our lack of imagination.

Manageable and Unmanageable Managing

Imagine managing cheese products in India for a global food company or running a general hospital in Montreal under the Quebec Medicare system. Sounds pretty straightforward, right?

Now imagine that you have sold so much cheese in India that the company asks you to manage cheese for all of Asia. Or in Montreal you are asked to manage a community clinic apart from the hospital—to go back and forth between them or to stay in an office somewhere and shoot off emails.

In one region in Quebec, the government actually went nine times further. It designated one managerial position for nine different institutions: a hospital, community clinic, rehabilitation center, palliative care unit, and various social services. Gone were the nine managers who headed up those institutions, replaced by one manager to manage the whole works. Think of the money this saved. Think of the chaos that ensued.

Unmanageable Managing

Some managerial jobs are rather natural and others are not. Cheese in India sounds okay, but cheese in Asia? One health care institution sure, but two together (actually apart), let alone nine?

Why do we tolerate unmanageable managerial jobs? Years ago conglomerates were all the rage among corporations. If you knew management, you could manage all kinds of businesses together—say, a filmmaking studio with a nuclear reactor and a chain of toenail salons. That era passed, thankfully, only to be replaced by internal conglomeration. Now it’s fashionable for managers to manage perplexing mixtures of activities within the same business.

This happens because drawing charts is a lot easier than managing organizations. Think of all the money this saves, too. All you need is the Great Organizer sitting in some central office somewhere (a) clustering various businesses together on a chart, (b) drawing a box around each cluster, (c) designating a label for each box (cheese in Asia or Health and Social Services Centers in Quebec), (d) joining them all with lines to show who is the real boss, and (e) emailing the tidy result to all concerned—and condemned. What could be simpler than that? Or more complicated?

The Box Called Asia

They eat a lot of cheese in India but hardly any in Japan. What in the world is “Asia” anyway? Any continent that contains both India and Japan can’t be serious: I know of no two countries that are more different.

Have a look at a map of the world. Geographically at least, most of the continents look coherent, surrounded by seas: Africa, North as well as South America and especially Antarctica, even Australia. But how did Asia get in there? There is no sea to the west, nor does Europe have one to the east. The Asians can thank the Europeans, who designated the continents in the first place. The Europeans could hardly leave themselves out, let alone be lumped into Eurasia (Japan? India?), even if that is what the maps indicated. So they drew a line between Europe and Asia with no sea in sight. Not quite in the sand, mind you; they drew the line along a mountain range. (By this logic, Chile should also be a continent.) These mapmakers simply sliced Russia in two to fabricate where Europe ends and Asia begins.

People who used to make such maps now draw organization charts.

The Most Dangerous Manager

Let’s get back to business. You are managing cheese in Asia, except that people in some parts of Asia eat lots of cheese and others don’t. How are you to manage that?—especially when the person who took your old job in India, where most of your Asian sales already are, is managing cheese there perfectly well, thank you.

If you are smart, you won’t even try. But that won’t get you a promotion, say, to become the Big Cheese for the company’s food in all of Asia—kimchi and harissa and poutine as well as cheese. So manage cheese in Asia you must.

And that is when the problems begin. Please understand: there is nothing more dangerous than a manager with nothing to do. Managers are energetic people—that’s one reason why they got to be managers in the first place. Put one into an unmanageable position, and he or she will find something to do. Like organizing retreats where the cheese managers from India, Japan, Outer Mongolia, and Papua New Guinea can join in the search for “synergies”—ways to help each other sell product that people don’t want.

Otherwise, it’s boring to sit in the regional head office in Singapore (the center of the Asian non-continent), so into an airplane goes our energetic manager. Not to micromanage, mind you—that’s out of fashion. Just to drop by, to have a look. “I’m your boss, in charge of cheese for Asia,” you say, hovering over the manager in charge of cheese for Japan. “Thought I would drop in, you know, to chat. But while I’m here, let me ask you a few innocent questions: How come cheese is not moving in Japan? Isn’t the job of a business to create a customer? They eat Korean kimchi here, don’t they, just like they eat Indian chutneys in Piccadilly Circus? So why not Gorgonzola in the Ginza?”

Beyond the Boxes

A hospital all in one place is a natural entity. Selling cheese in India also seems natural enough. But beyond that, expecting someone somewhere to manage because someone elsewhere drew a box on a chart isn’t necessarily natural at all. Surely we can organize ourselves outside the boxes.

The Board as Bee

Under the label “governance,” boards of directors have been getting a good deal of attention lately—maybe more than they deserve, because there is often more status than substance in what boards do. They do have constructive services to provide as well as one governance role to perform, but even that is limited.

Among the constructive services are providing advice to management, simply acting as a sounding board, and helping to raise funds. And the very presence of influential members can enhance the reputation of the organization, as well as connect it to important centers of power.

When the Board Buzzes

The real governance role of the board is to oversee the activities of the senior management—in three respects. First is the appointment of the chief. (I use the word chief rather than CEO to include the heads of nonbusiness organizations.) Second is assessing this person’s performance. And third is replacing him or her when necessary. Sometimes a board member must also act temporarily in the chief’s place if he or she becomes incapacitated.

Otherwise the board does not control the organization. It appoints the chief who does that, and then appropriately backs off. Chiefs have axes, with clout; boards have gavels, that make noise. Of course, if a board lacks confidence in the chief, it has to replace, not second-guess, him or her. The tricky part is that the board cannot do this often.

Think of the board as a bee, hovering around a chief who is picking flowers. That chief has to be careful. A bee can sting only once, so it had better be careful, too. True, a board can sting more often than a bee—it can replace one chief after another. But that would raise concerns about its own competence. Besides, most of the current board members probably appointed the person they want to replace.

The Board Apart

Board meetings may be held regularly, but usually not frequently, so its members are quite removed from what goes on in the organization. How, then, can they even know when to replace the chief, given that their main channel into the organization is through that very same chief?

Compounding the problem of selection, assessment, and replacement is that board members typically have higher social status than most of the other people in the organization, which hardly helps them assess internal candidates for the job of chief. Indeed, this can introduce a bias toward the selection of outsiders. Moreover, high-status people on the board may be inclined to select people in their own image, who may not relate well to the people they are intended to manage.

There is a label for people who relate well to “superiors” and badly to “subordinates,” as discussed in the earlier story on selection: “kiss up and kick down.” They’re great at hobnobbing with big shots but lousy at working with regular shots.

Beware of the Buzz

Of course, boards vary in their practices, depending on the nature of the organization being governed. While the foregoing discussion may apply especially to widely held corporations, in companies that are closely held, especially by an owner, everyone knows who has the power—and it’s not the board.

The directors of businesses are usually businesspeople themselves. But what happens when they sit on nonbusiness boards—NGOs, hospitals, universities, and so on? Those who come with the belief that business knows better can be a menace, posing a double danger: they may be more inclined to meddle and to appoint people like themselves to run these places. Do businesspeople understand any more about education and health care than do educators and physicians about business?

These organizations are different: they have more complicated stakeholder relationships, their performance is less easily measured, and their staff may be more like members than employees. As is discussed in a later story, business is not the “one best way” to manage everything.

So what is my bottom line here? Boards are necessary but problematic. Their members need to have an acute sense of what they don’t know, and how to get better informed, without becoming excessively informed. And all boards need variety in their membership to temper their own limitations. They must also be aware of their buzz even more than their bite.