CHAPTER

19

Professionalism and Responsibility

FOR ALL THE GOOD THAT COACHING CAN DO, THERE ARE NO GUARANTEES. YOUR OPTIMISM NEEDS TO BE BALANCED WITH A REALISTIC AND PRAGMATIC PERSPECTIVE ABOUT CLIENTS AND ORGANIZATIONS. ALONG THE WAY, THERE MAY be situations that challenge your values as a coach—unfulfilled commitments, goals that shift unpredictably, or pressure to reveal protected information. While these situations are unusual, you need to be prepared to deal with them as well as other challenges. Consider the following reminders.

![]() First of all, do no harm. When your sense of fairness is aroused, be careful about being too activist and becoming a client-crusader. Consider all the possible risks of your actions. Doing less is often the best response.

First of all, do no harm. When your sense of fairness is aroused, be careful about being too activist and becoming a client-crusader. Consider all the possible risks of your actions. Doing less is often the best response.

![]() Put what is best for the client and sponsors ahead of your own needs for professional activity. Align the coaching process with their expectations.

Put what is best for the client and sponsors ahead of your own needs for professional activity. Align the coaching process with their expectations.

![]() Become familiar with professional guidelines about ethical behavior, commitments to clients, confidentiality, and role boundaries for executive coaches or from related fields of practice.

Become familiar with professional guidelines about ethical behavior, commitments to clients, confidentiality, and role boundaries for executive coaches or from related fields of practice.

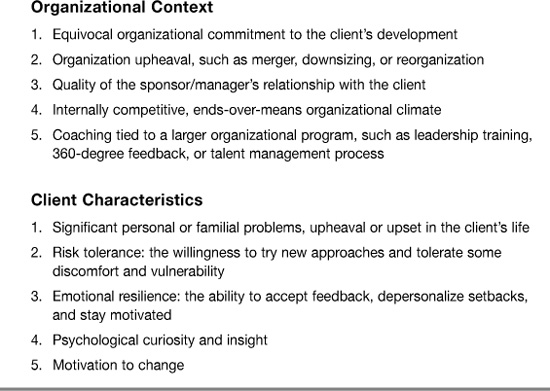

Challenges the Client and the Organization Pose

Occasionally, every experienced coach has to deal with challenges to his or her operating values. In the spirit of prevention and to keep such challenges to a minimum, it is best to explore potentially negative factors when you are contracting a coaching engagement. Organizationally specific negative indicators to the success of coaching include ambiguous or qualified support for the client’s development (e.g., threat of termination looming over the client); an absent, oppositional, or skeptical manager (e.g., manager expresses little optimism that coaching will help the client); organizational upheaval and uncertainty (e.g., downsizing and mergers); and a highly political, low-trust organizational culture (e.g., aggressive internal competition where your loss is my gain). There may be other organizational factors that threaten to distract your client from a developmental focus. If you encounter any of these challenges, remember that it is easier to delay or step away at the outset than after coaching begins. At the very least, you can contract to build in needed organizational support—such as more contact with sponsors, adequate time for coaching, checkpoints with all participants, or even an early process review meeting—in response to the challenges that your contracting conversations reveal.

In addition, not all clients will be able to use coaching to the same degree or, in some cases, at all. Clients may have characteristics that make them unlikely to benefit from coaching. While there may be some indication of client-specific challenges to coaching in your pre-coaching interactions, they are more likely to surface in the early stages of the process. They can include a personal or family crisis, extreme defensiveness, emotional fragility, or low motivation to understand and change behavior. If these characteristics are apparent during the contracting phase, you may decide to step away, delay, or adjust your contract. If you do move ahead, contracting a coaching process that provides more latitude can help to mitigate these client-based risk factors. There are times when you must adjust expectations for progress downward so that a client with significant limitations can make productive use of coaching. You may find it in your client’s best interest to slow the pace, draw in more involvement of others, or redefine progress indicators to be more in line with what that particular client can manage. The aim is to make your coaching process robust enough to accommodate needed adjustments.

For a summary of both organizational and client-specific variables that can compromise coaching, see Figure 19-1.

Figure 19-1. Coaching caveats1

Coaching Challenges

There are also several temptations and vulnerabilities inherent in the coaching role that require both self-awareness and self-management on your part. For executive coaches, confidentiality is one issue requiring special vigilance. This begins with being very clear in distinguishing between confidential information (generally whatever the client, or anyone else, tells you, as well as your own observations) and that which can be shared (coaching objectives, general statements about progress, and the development plan).

While in principle these are easy to separate, in practice the boundaries may be challenged, even inadvertently. A sponsor may ask you how the client handled 360-degree feedback; an HR person may ask when the client will be ready to move into an open position; a colleague may express extreme distrust and animosity toward your client. In these awkward moments and others that may arise as you come in contact with the organizational context, you need to remain confident in your role, even if that means sidestepping the implied demand or pressure for information. It is always safe to listen, restate what you are hearing, ask clarifying questions, and if need be, reassert the requirements and boundaries of your role. You need to be willing to disappoint, or even frustrate, whoever is making the request, confident that in doing so, you are honoring your commitment to the client and the process. Even when you are clear about the ethical response, however, these moments can be lonely or even unsettling, and you would benefit from discussing them with a trusted colleague or your case supervisor.

Therapists and other helping professionals use the concept of containment (introduced in Chapter 13) in creating safety for clients and coaches can borrow it to expand their grasp of confidentiality. As a coach, you are the container of your client’s hopes, fears, resentments, and other difficult feelings. You provide a safe place where the client can explore these reactions.

Contracting about confidentiality is the first element of providing that safe container, but there are three others. The second element is your competence as a coach. This arms you with knowledge about coaching practices so that you can anticipate challenges and adjust the process accordingly. The third element is self-management, which asks you to know your own vulnerable moments, anticipate them, and respond intentionally rather than impulsively. Lastly, if you are to provide your clients with a structurally sound safe container, you must have your own safe haven in which to discuss quandaries and challenges. This means that you have established a relationship with a coaching mentor or case supervisor in advance of when you need it. These four mutually supportive elements provide the professional support that you need to create a safe and productive relationship with clients even when faced with unexpected difficulties (see Figure 13-1).

In every engagement, preserve the integrity of your relationship with the client. To do this, you need to protect the boundaries between providing consultative expertise, facilitating client self-insight, and empowering change. Difficulties arise if your clients are particularly needy, bereft of ideas, and pressure or tempt you to provide recommendations or answers. There may be rare times when it is appropriate to be more directive; for example, if your client is engaged in blatant self-sabotage (e.g., emotional outbursts, verbal attacks on others, or being overtly oppositional). In the majority of situations, however, the power inherent in your role as coach is best used to cultivate the client’s self-efficacy instead of responding to momentary pressure to save the client or solve the client’s problems.

There are also challenges to your boundaries that arise after the engagement is concluded. The guiding principle is the importance of being sensitive to your client’s potential exposure and vulnerability even after coaching has ended. It is also vital to demonstrate responsible handling of a former client’s feelings. For example, you will be expected to maintain confidentiality indefinitely. Continue to treat your clients as clients even after coaching has ended. This means avoiding social contact or any change in your relationship with them (related matters are discussed in Chapter 17 on closure). In this regard, consulting projects that happen to have a client in an important role can be especially challenging, and it may be best to delay your participation until after coaching has concluded. If you have former clients in an organization where you are currently coaching or consulting, consider informing them in advance that you may be observed on their premises and reaffirm your confidentiality commitments to them.

Your own personal needs may also exacerbate boundary challenges. In becoming an exceptional coach you assume responsibility for a higher level of self-monitoring and self-management. You should not seek to satisfy your own needs for companionship, acceptance, credit, admiration, or even more business through a coaching relationship. However, all coaches have human frailties and want to be helpful, so there may be times when you feel weaker in terms of your commitment to the values inherent in the role. Some of those times are predictable, as when you remind yourself that being too helpful with needy clients is less valuable than supporting and empowering them. Other especially sensitive challenges to your role that may tap into your own needs can emerge from your contacts within the organizational context: with the HR manager who controls your future work in the organization and who asks to know what the client thinks of him; with the manager who asks you to convey her evaluation of the client because she doesn’t have the time; with a client who asks you to discuss the development plan with his manager because they have a strained relationship. These individuals and others will challenge you to stay within the boundaries of effective coaching.

In maintaining boundaries and confidentiality in coaching, internal coaches have a more complex task than external coaches. Most internal coaches have responsibilities besides coaching: leadership development, training, talent management, organization development, and HR generalist activities, for instance. As a result, internal coaches often have multiple contact points with coaching clients or their client’s colleagues and direct reports. (This subject is presented in detail in Chapter 20 on the role of the internal coach).

Some internal coaches seek to reduce such contact points by providing coaching services only to divisions of their organizations where they have no other responsibilities. However, it is the responsibility of the organization to create an overall structure that protects the role of its internal coaches. Clear, organizationally supported guidelines for internal coaching can be very helpful, and these policies need to be clarified and confirmed each time an engagement is contracted.

An anchor in navigating difficult situations is to become familiar with practice and ethical guidelines in larger and more established helping professions, such as psychology, social work, medicine, and so on. Whether or not you are a member of one of these professions, their ethical standards are usually broadly applicable to coaching and may help guide your choices in difficult situations.

There are many facets to coaching as well as many potential pitfalls. Here, Steve bumped into a very common one—when a client asks a coach to go outside the established contract to do something more personal or instrumental for him. It’s not uncommon for clients to ask for recommendations or consulting help, rather than coaching. Help with résumés sometimes comes up in response to frustration on the job, conflicted relationships with more senior leaders, or a values clash with the manager. As a coach, however, your agreement with the sponsoring organization is to help clients develop in their context, not to help people leave the company or change the organizational culture.

On the other hand, clients do sometimes have legitimate reasons to aspire to an internal move, promotion, or even job reconfiguration. As long as you determine that these desires are aligned with the client’s career direction and are not a flight reflex caused by a difficult situation, coaching can continue very productively. The goal may shift toward strategizing and empowering the client to build the necessary relationships and have the needed conversations with decision makers. Ideally, this shift is led by your client, transparent to the sponsors and supported by them.

Again, it is part of your role as coach to help bring alignment between your client’s actions and the situational expectations, even while you are primarily supporting the client in stretching toward his or her aspirations.

Takeaways

![]() There are organizational and client-specific challenges to effective coaching; to the extent possible, try to size them up during contracting and design a robust process that can accommodate adjustments.

There are organizational and client-specific challenges to effective coaching; to the extent possible, try to size them up during contracting and design a robust process that can accommodate adjustments.

![]() It may be prudent to withdraw yourself from consideration for a coaching assignment when you sense mixed organizational support and a client with significant limitations.

It may be prudent to withdraw yourself from consideration for a coaching assignment when you sense mixed organizational support and a client with significant limitations.

![]() Containment is a broad concept supporting confidentiality. It includes clear confidentiality guidelines, knowledge of effective coaching practices, knowledge of our own vulnerabilities, and the availability of a case supervisor for those times when you need professional support.

Containment is a broad concept supporting confidentiality. It includes clear confidentiality guidelines, knowledge of effective coaching practices, knowledge of our own vulnerabilities, and the availability of a case supervisor for those times when you need professional support.

![]() If you are an internal coach, you need to pay particularly close attention to confidentiality, boundaries, and contracting. In addition, organizational policy support for the internal coaching process is vital, given the multiple roles that internal coaches perform and the many relationships they have in their organizations.

If you are an internal coach, you need to pay particularly close attention to confidentiality, boundaries, and contracting. In addition, organizational policy support for the internal coaching process is vital, given the multiple roles that internal coaches perform and the many relationships they have in their organizations.

![]() Review ethical guidelines from other professions, especially those you are part of, to help anchor your coaching practice; tailor those guidelines to your Personal Model of coaching and then adhere to them.

Review ethical guidelines from other professions, especially those you are part of, to help anchor your coaching practice; tailor those guidelines to your Personal Model of coaching and then adhere to them.

![]() Utilize a coaching mentor, case supervisor, or coaching colleague as a discussion partner when cases are at risk of crossing boundaries or you are experiencing pressure to do something that does not feel right to you.

Utilize a coaching mentor, case supervisor, or coaching colleague as a discussion partner when cases are at risk of crossing boundaries or you are experiencing pressure to do something that does not feel right to you.