CHAPTER

3

Foundations and Definitions

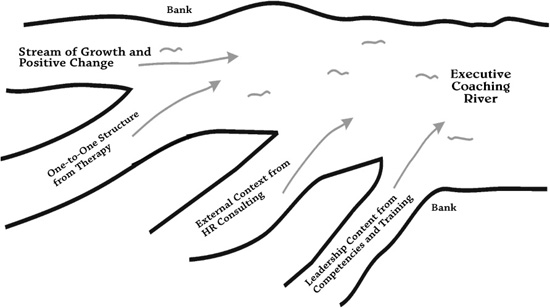

THREE STREAMS OF PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE CONVERGE IN EXECUTIVE COACHING. THE FIRST STREAM IS REFLECTED IN THE ONE-TO-ONE STRUCTURE OF COACHING AND COMES FROM THE CONFIDENTIAL TALKING PROCESS THAT therapists and counselors employ. As therapy became more common and acceptable in the United States in the 1960s, some of those clinical practitioners were invited to apply their skills to the needs of corporate executives, even before executive coaching was labeled as a practice in its own right.

A second stream taps activities of consultants who were engaged to help with organizational and human resources challenges. They normalized the general use of external professionals when special expertise was needed by organizations. As coaching gained traction, the precedent of consulting made it easier to use outside experts to help individual managers and executives with their leadership challenges.

The third stream contributes content and processes that were designed for leadership development programs. Paralleling the growth of coaching, organizations were also experimenting with defining leadership competencies. They relied especially on assessment tools and individual development planning processes. Once competencies were identified, it was possible to design leadership courses that often combined content, individual feedback, and action learning elements for a complete development experience. Executive coaching draws directly from the concepts and content of the leadership development movement, which has continued to generate new ideas about what it means to be an effective leader.

Along with these streams of influence (illustrated in Figure 3-1), banks or boundaries were defined to differentiate executive coaching from other interventions. Specifically, executive coaching is unique because it embraces the following characteristics:

Transparency: The process is open and observable.

Shared Responsibility: The coach leads the process while the client leads change.

Facilitative Style: The coach helps identify client choices while minimizing being directive.

Client-Focused Narrative: The client’s stories and perspectives dominate discussions.

Organizationally Sponsored: Engagements are supported by representatives of the organization, such as human resource professionals and client managers.

Work-Related Goals: Client development goals target important managerial and leadership areas, and implementation occurs in day-to-day performance changes.

Nonhierarchical Relationship: The coach has no formal authority over the client.

Limited Confidentiality: Coach-client conversations are private, although the process is transparent and plans are shared with the organization.

Staying within the banks of executive coaching requires the following coaching skills:

Figure 3-1. Streams and banks of executive coaching

![]() Being able to describe what you mean by executive coaching

Being able to describe what you mean by executive coaching

![]() Establishing your credibility as an expert on the coaching process, not the client’s issues or field of work

Establishing your credibility as an expert on the coaching process, not the client’s issues or field of work

![]() Remaining proactive in managing the evolving relationships with the client and sponsors

Remaining proactive in managing the evolving relationships with the client and sponsors

![]() Establishing appropriate goals as the coaching unfolds and being open to what emerges, while maintaining an outcome orientation

Establishing appropriate goals as the coaching unfolds and being open to what emerges, while maintaining an outcome orientation

![]() Shifting the responsibility for process ownership toward the client during the course of the coaching

Shifting the responsibility for process ownership toward the client during the course of the coaching

![]() Maintaining hope and optimism about positive outcomes and change, even as the client faces practical reality and organizational challenges

Maintaining hope and optimism about positive outcomes and change, even as the client faces practical reality and organizational challenges

![]() Tying coaching to current challenges to increase the client’s longer-range career potential and learning appetite

Tying coaching to current challenges to increase the client’s longer-range career potential and learning appetite

![]() Finding ways to be personally authentic, neither impersonal nor clinical, but always professional

Finding ways to be personally authentic, neither impersonal nor clinical, but always professional

Definitions of Coaching

The streams and banks metaphor provides coaches with ways of describing coaching and differentiating it from other interventions. This helps clients and coaches understand both what coaching is and what it is not. Doing so is part of the larger task of shaping a Personal Model.

In definitions of executive coaching, the term client is particularly important. For some coaches, the client is the organization; for others, the client designation is shared between the organization and the person in the coaching relationship. In this book, the word client refers exclusively to the individual seeking growth and development through coaching. It assumes that the coach-client relationship is the primary vehicle for change rather than the coach’s relationship with the organization or its representatives (e.g., the client’s manager or the Human Resources partner), who are referred to here as sponsors.

Here is the definition of executive coaching that underlies this book:

Executive coaching is a one-to-one development process formally contracted between a professional coach, an organization, and an individual client who has people management and/or team responsibility, to increase the client’s managerial and/or leadership performance, often using feedback processes and on-the-job action learning.

This definition implies several important distinctions between executive coaching and other activities. First, it recognizes that the activity of managers coaching their employees is different from executive coaching because of its authority structure and lack of confidentiality. Second, while the term mentoring is sometimes used synonymously with coaching, this book views it as a different activity. Mentoring is valuable in supporting career access and advancement but does not focus on performance improvement. Third, training and development programs can have similar content to coaching, but they are delivered in group settings rather than the one-to-one structure of coaching.

There are, of course, a variety of other definitions that have been given to executive coaching. Several alternative definitions by other practitioners are shown here. Each one reflects that practitioner’s favored theories or approaches (indicated in parentheses) to fostering learning and change:

The essence of executive coaching is helping leaders get unstuck from their dilemmas and assisting them to transfer their learning into results for the organization.1

—MARY BETH O’NEILL

(organization development, or OD, values)

Action coaching is a process that fosters self-awareness and that results in the motivation to change, as well as the guidance needed if change is to take place in ways that meet organizational needs.2

—DAVID DOTLICH AND PETER CAIRO

(relationship focused on business results)

Coaching is not telling people what to do; it’s giving them a chance to examine what they are doing in light of their intentions.

Our job as coaches will be to understand the client’s structure of interpretation, then in partnership alter this structure so that the actions that follow bring about the intended outcome.3

—JAMES FLAHERTY

(phenomenology)

A masterful coach is a vision builder and value shaper … who enters into the learning system of a person, business, or social institution with the intent of improving it so as to impact people’s ability to perform.4

—ROBERT HARGROVE

(transformational change)

The aim of coaching is to improve the client’s professionalism by discovering his or her relationship with certain experiences and issues … to encourage reflection … to release hidden strengths … to overcome obstacles to further development … to investigate the extent to which aspects of the client’s behavior are causing or prolonging the issues.5

—ERIK de HAAN and YVONNE BURGER

(learning, human potential)

The Intersection of Executive Coaching and Consulting

The goals of executive coaching usually can be categorized under one or more of the following headings: strengthening a client’s self-management; interpersonal effectiveness; and leadership impact. When useful, traditional managerial skills such as contracting for performance, delegating, and providing feedback can be included under the leadership heading.

Of course, case-specific coaching goals are always tailored to the client’s needs and interests. Examples of a client’s needs might include being a stronger team leader; influencing in complex systems; clarifying a vision and goals; taking on larger or global responsibilities; or managing multilayer execution. There may be other aspirations as well, tied to that leader’s unique blend of skills, personality, career aspirations, and challenges.

Some executive coaches bridge their work into the content areas of executive roles—areas such as business strategy, integration of acquisitions, or talent management processes, for example. This practice is particularly true of consultants, human resource professionals, and organizational psychologists who have added coaching to their practices. However, this melding can often be confusing to clients. While coaching and consulting can be synergistic, the activities are quite different. Coaching leverages the client relationship within a process that fosters self-discovery, whereas consulting brings particular content expertise to the foreground. In overly general terms, coaches ask in order to explore, while consultants ask in order to tell. In this respect, coaching is more aligned with the values of organization development (OD), which seeks to draw out answers that reside in the collective consciousness of the client.

Experience indicates that coaches who also consult need to make a clear separation between these two activities in order to prevent client confusion. In building your Personal Model, it is important for you to make a conscious choice about your coaching/consulting balance. Without acknowledging that boundary, you are likely to slip into consulting mode because it is what clients are used to. Said differently, it is important for coaches who also consult to be clear with themselves and with clients about their roles in every engagement and use different processes within those roles. It is also important to reaffirm roles during the course of coaching engagements if boundaries are challenged or become blurred. For detailed distinctions among executive coaching, consulting, personal coaching, and therapy, see Exhibit 1, which appears among the supplementary materials at the end of this book.

Understanding Adult Change and Growth Through Theories that Apply to Coaching

Most people have strongly held beliefs about how people change and grow. Some may be rooted in philosophical tradition (e.g., What doesn’t destroy me makes me stronger), while others may come from religious teaching (e.g., Turn the other cheek). Still others may reflect values imprinted from an individual’s upbringing (e.g., Education is the key to success). These belief structures exist for coaches, clients, and sponsors, whether articulated or not, and they act as lenses through which behavior is interpreted. In order for you to articulate your Personal Model and apply consistent professional judgment, you need to identify your own philosophy of how people change and grow and make it overt and describable, at least to yourself. For example, you may believe that clients experiencing transitions (e.g., into leadership roles or entering midlife or a second career) are particularly open to growth, or you may know you would rather coach younger managers before they are set in their ways.

In reflecting on your own point of view, it is useful for you to become conversant with a repertoire of broader theories of adult change. These formalized theories of adult change and growth represent eddies in that first stream from therapy and counseling that flowed into coaching. They encapsulate many useful concepts and models about adult growth.

Six of these theories are highlighted here because they have been important influences on coaching practice; we encourage you to try on these lenses. The six theories are psychodynamic, life stage, behaviorist, emotional intelligence/positive psychology, existential/phenomenological, and cognitive. None of them is inherently more accurate than any of the others; each provides a useful perspective, or lens, about how adults establish and change behavior, while at the same being applicable to coaching.

All of the approaches are likely to be familiar to executive coaches with graduate training, but you may not have realized that all have been applied to coaching. In addition, any of them could be part of shaping your Personal Model or definition of coaching. As you try on these different lenses, you may find one or more of the theories especially engaging and helpful in increasing the acuity of your observations. In this regard, studying them helps you articulate your own change philosophy and expand the range of your thinking.

Since the descriptions of each approach could take a book by itself, this chapter merely highlights how each could translate into a coaching approach:

![]() Coaches who apply psychodynamic thinking to their work are focused on revealing insights about the client’s motivations, choices, and defenses, especially through exploring the client’s formative emotional experiences. They may also leverage the relationship between coach and client and transference reactions, in which the client may experience thoughts and feelings in response to the coach that are reminiscent of other important relationships, such as with a parent.6

Coaches who apply psychodynamic thinking to their work are focused on revealing insights about the client’s motivations, choices, and defenses, especially through exploring the client’s formative emotional experiences. They may also leverage the relationship between coach and client and transference reactions, in which the client may experience thoughts and feelings in response to the coach that are reminiscent of other important relationships, such as with a parent.6

![]() Coaches who apply life-stage conceptions of change look for the accomplishment of life-stage challenges and successful transitions. They also encourage clients to view change as a natural part of growth and plan for transitions and challenges likely to be prominent in future stages.7

Coaches who apply life-stage conceptions of change look for the accomplishment of life-stage challenges and successful transitions. They also encourage clients to view change as a natural part of growth and plan for transitions and challenges likely to be prominent in future stages.7

![]() Coaches who emphasize a behaviorist approach target specific, manageable, behavioral change goals and foster an environment that reinforces those desired changes. They focus on putting aside past ineffective behavior by changing the context and the feedback, rather than by increasing the client’s self-insight.8

Coaches who emphasize a behaviorist approach target specific, manageable, behavioral change goals and foster an environment that reinforces those desired changes. They focus on putting aside past ineffective behavior by changing the context and the feedback, rather than by increasing the client’s self-insight.8

![]() Coaches who use emotional intelligence as a lens emphasize helping clients improve their emotional self-management, social awareness, empathy, and effectiveness in relationships. Related to emotional intelligence is the positive psychology movement. When used in coaching, positive psychology emphasizes strengths and uses insights about them to chart a path toward effective leadership. These ideas have been very appealing to coaches and clients who want to tap into the energy generated by building on success.9

Coaches who use emotional intelligence as a lens emphasize helping clients improve their emotional self-management, social awareness, empathy, and effectiveness in relationships. Related to emotional intelligence is the positive psychology movement. When used in coaching, positive psychology emphasizes strengths and uses insights about them to chart a path toward effective leadership. These ideas have been very appealing to coaches and clients who want to tap into the energy generated by building on success.9

![]() Coaches who leverage existential/phenomenological thinking explore the client’s view of the world and empower the act of choosing, even though uncertainty can never be eliminated. Some coaches may view these ideas as bleak or fatalistic; others are truly energized by supporting choice in the face of real-world pressures.10

Coaches who leverage existential/phenomenological thinking explore the client’s view of the world and empower the act of choosing, even though uncertainty can never be eliminated. Some coaches may view these ideas as bleak or fatalistic; others are truly energized by supporting choice in the face of real-world pressures.10

![]() The most widely used approaches in clinical and counseling psychology, cognitive perspectives about change (sometimes called cognitive behavioral or rational emotive) are favored by coaches as well. They combine behavioral outcomes with self-insight about negative or self-limiting thoughts and the behaviors they engender.11

The most widely used approaches in clinical and counseling psychology, cognitive perspectives about change (sometimes called cognitive behavioral or rational emotive) are favored by coaches as well. They combine behavioral outcomes with self-insight about negative or self-limiting thoughts and the behaviors they engender.11

While each of these six conceptual lenses has unique elements, they also naturally overlap. Examples include a cognitive approach that leverages emotional intelligence ideas, life-stage transitions that incorporate an existential stance, and, of course, behaviorist thinking overlaps with almost all of the other approaches in terms of tangible, behavioral outcomes to coaching.

In addition, there are other useful conceptions of adult development, which come from streams other than individual change but have been applied to coaching, such as learning models and systems approaches.12 Increasing your awareness of the many ways that change can be understood is a valuable endeavor. It will help you articulate your own beliefs about adult growth and influence how you will apply those beliefs in your coaching model and practice.

Consider the following questions as prompts to your own conceptions of adult change:

1. What do you believe are the most important influences shaping personality and interpersonal style?

2. What are the most powerful leverage points in fostering changes in behavior?

3. In your own experiences, what influences have helped you change and grow?

4. How do you conceptualize the connections between feelings, thoughts, beliefs, and behavior?

The Range of Coaching Services

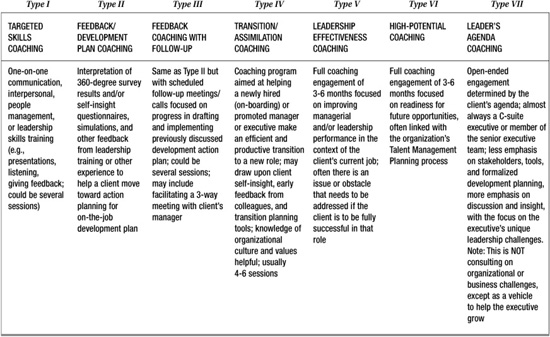

Even though descriptions of coaching usually focus on those services that are delivered in a typical three- to six-month engagement, there are related interventions that fulfill our definition of executive coaching. Coaching has been viewed along a continuum, from shorter and more targeted, to longer and more emergent interventions. This book envisions seven distinct types of coaching that range along this continuum (see Figure 3-2). Each one differs from the others in important respects. All have a focus on individual development in the work context, although breadth and other features vary. You may not be familiar with all of them, but becoming familiar with more of them could expand your practice, whether you are an internal or external coach.

Moving from left to right in Figure 3-2, the types of coaching are arranged by degree of coaching skill and experience required, as well as the likelihood that an internal coach would be delivering this type of coaching versus an external coach. Type I coaching is similar to a tutorial but focused on an important management or leadership skill tailored to the needs and abilities of the client. While this type of coaching may not arise frequently, internal coaches connected with leadership development functions readily deliver this type of coaching in a few sessions. Types II and III coaching are similar because they are tied to a developmental experience (e.g., leadership development program, assessment feedback, or 360-degree surveys) and because they are aimed at having the client draft a well-founded development plan. The difference is that Type III coaching includes follow-up meetings after the initial feedback discussion. These follow-up meetings require additional coaching skill in order to adjust and confirm the implementation of a productive development plan.

Figure 3-2. Executive coaching continuum

The specifics of Type IV coaching are unique for each organization. What is common is the goal of making a transition to a new job smoother and quicker. It may be applied to current employees or new hires (i.e., on-boarding) but the structure of these engagements can vary widely. Type IV coaching has become very widely used and gives internal coaches an opportunity to leverage their organizational knowledge, although external coaches deliver it as well.

Types V and VI coaching are most often thought of when the term executive coaching is used. They differ only in the need that triggers the engagement: Type V focuses on improving current performance, and Type VI supports a client’s promotability to a likely future job or organizational level. What is profound about this distinction is its effect on how coaches will contract and conduct the engagement. Type V, in particular, can be challenging for all parties because job jeopardy may be implied, depending upon the severity of the need for behavior change. Type VI, on the other hand, challenges the coach and client to extrapolate to future job challenges and create a development plan with that vision as the focus. Typically, both types of coaching are six-month engagements.

Last, Type VII coaching is uniquely delivered to those senior, or C-suite, executives (e.g., chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and so forth) who control their own budgets and developmental agendas. Goals are quite variable—from leadership style concerns, to career quandaries, to just having a confidential discussion partner for leadership issues facing the executive. As long as the client remains the focus, this intervention stays within the boundaries of executive coaching. As indicated by the flow of the continuum, highly experienced external coaches almost always deliver this type of coaching.

All of these coaching interventions are in active use across the spectrum of the executive coaching field. You may choose to specialize in one or more of them while at the same time targeting your growth toward those you would like to add to your practice.

Part II of this book is aimed at the third input to your Personal Model: your awareness of and preferences for executive coaching practices. As such, Part II divides the challenges of an executive coaching engagement into sixteen major topics, from contracting to concluding the engagement and everything in-between. Some chapters are not aligned with the sequence of an engagement but are important to consider, such as dealing with differences and professionalism. Each of these content chapters includes a case study that illustrates aspects of that chapter’s focal topic, followed by a case supervisor’s commentary. The concluding chapter of Part II addresses the special challenges of being an internal coach, a role of increasing importance in management and executive development.