Chapter 9

The Evolution of the Computing Market

Advertising is legitimized lying.

— H. G. Wells

Where is cloud computing today? Where is it going? This chapter answers those questions.

The answers do not include a bunch of obvious, generalized statements, such as “The cloud will expand in the enterprise moving forward,” or “Data will continue to grow in the cloud.” Thanks, Captain Obvious. Nope, in this chapter we focus on where the cloud market is now, how it will likely grow, and point out trends that are more difficult to perceive. In many cases, we may push back on the business plans of some cloud providers while validating others. Let’s get started.

First, understand that cloud is the next phase of computing, which means it will pay off to get cloud done right the first time. Some enterprises already got a few (or many) cloud things wrong. If they don’t correct course, companies that do cloud wrong will see costs go up while the quality of their services and products goes down. Meanwhile, more innovative companies will step up and take their market share. These disruptor companies will learn how to effectively leverage cloud computing technology and cloud services such as AI. Companies that provide better customer experiences using better technology will displace the companies that don’t understand until it’s too late that cloud adoption is life and death.

So, how do you get on the right cloud track? It’s not about understanding the details of what I’m about to tell you, it’s about understanding the general trends of how I see the market evolving. In some places, I make educated guesses as to what will likely happen based on existing data and trends. Some patterns have already emerged, so it’s not a question of if they will occur; it’s an educated guess as to how they will play out from here. The most important aspect is to get the gist of what will probably happen, its relationship to how and when you adopt the technology, how the technology works in the enterprise now and moving forward, and ways you can weaponize the technology for your own business advantages. This means spotting trends that many others don’t see and leveraging them as true force multipliers.

Again, I provide an objective take on each topic. I’ll talk about the good, the bad, and ways you should consider the topic from the viewpoint of your own business requirements. Of course, you should also consider your own life experiences and interpret what I’m saying from your point of view. I never claim that I’m always right, and I always welcome challenges to my thinking from those who read my books or articles, take my courses, or follow me on social media. I recognize the fact that anyone who does not want to hear other points of view or gets inordinately defensive about their own should perhaps be reconsidered as a reliable source of information. With that disclaimer out of the way, let’s get to it.

Forced March to the Cloud?

It’s Monday, you’re visited by two “suits” who insist you must move faster to the cloud, and they give you a deadline to get more applications and data moved over to public cloud providers. If you do not meet that deadline, they explain that your systems will be at greater risk and the costs to maintain those systems will skyrocket to the point that they put your business in jeopardy.

What did you do to deserve this? Are these strong-arm tactics from a tyrannical government that wants to control the future of your business? The local mob?

No. This is what happens when an industry shifts its resources to an emerging technology (in this case, cloud computing, in which you’re only partially invested) and rapidly removes resources for the technology that runs your business day-to-day. You end up with fewer maintenance updates to those systems, little or no innovation, and eventually you have no choice but to move onto the new platforms. If you don’t, your business will “die the death of a thousand cuts.” The lack of support and innovation from your existing business systems will erode your IT footprint to the point that your business will lose a great deal of value.

Is this fair? No. However, we’ve seen this play out before. You don’t see many 30-year-old computers around, even though they would likely work to spec with their original software and operating systems restored. Technology providers eventually “sunset” the technology you’re using, which will force a move to newer and hopefully better technology.

We saw these shifts during the rise of PCs in the 1980s, then the rise of distributed systems, and now the rise of cloud computing. How the supply side of the industry makes investments in R&D and new innovations will move enterprises off older technology, no matter whether enterprises want to move or not. The provider shift to cloud investments will force your shift to cloud consumption at or around the same time frame. If you don’t shift, you’ll be stuck with undermaintained technology. This could be a security system that does not get consistent updates to do battle with new and emerging threats, or an operating system that does not receive driver updates to support new hardware, and so forth. It’s time to ask yourself, Where is your business positioned on its forced march to the cloud?

The Shift in R&D Spending

Let’s just get this out of the way: You can’t really put the R&D spending shift at the feet of cloud providers. Having been a technology products and services CTO for years, I know the name of the game is to focus on emerging markets and investments in those markets to support the growth of a technology business. The larger technology players (certainly the enterprise technology providers that have been around for decades) are acting in their own best interests by shifting R&D investments to technologies that focus on the cloud computing market and away from traditional systems that are found in data centers. What’s most interesting is that many of these companies still make 80 percent of their profits from traditional or legacy business, but they are not pushing more investments into improving that technology. Instead, their focus is on shiny new objects that promise better growth because the industry, technology press, and investors are laser-focused on cloud computing.

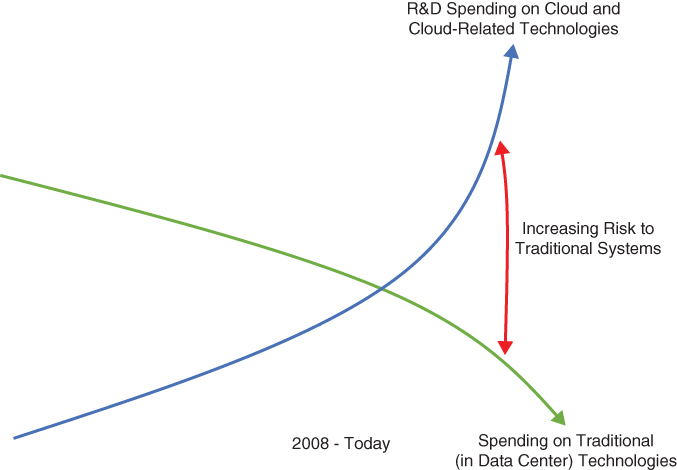

Figure 9-1 depicts how this shift played out since the start of the cloud computing boom around 2008. That’s when spending on R&D and innovation for core enterprise technology companies shifted from traditional to cloud-based systems, no matter what aspect of technology they provided, including databases, networking, security, and operations. Most R&D is now focused on cloud computing, which the industry views as the next evolution.

FIGURE 9-1 There is a vast difference in the money now spent to develop cloud-based technologies versus traditional computing technology. Approximately 80 percent goes to the development of cloud computing–focused products and services while 20 percent goes to more traditional systems such as mainframes. Traditional systems are being left behind as R&D focuses on cloud platforms.

Of course, companies that maintain more traditional technology incur mounting risk, as you also see in Figure 9-1. As the gap widens between investments in traditional technology and newer cloud-based technologies, the risk and cost of maintaining traditional systems shoot up. Those who maintain this technology will see fewer updates to key system components and fading technical support with fewer talented support staff taking longer to respond to requests. Those who maintain these systems are already starting to notice.

At the same time, you may leverage cloud-related services from the same company at deep discounts, with exceptional support, and you’re typically dealing with the top talent. Again, this may account for only 20 percent of the provider’s business, but it’s getting 80 percent of their time and talent.

Leaving Systems Behind

So, how do you deal with the need to move into cloud computing and still maintain many existing systems for the foreseeable future? It’s all about learning to manage risk.

Figure 9-2 depicts the three levels your existing systems will probably move through, and the timing depends largely on how your technology provider invests in their technology. The bottom level is “Production Ready,” where the technology is near or at production quality. It might not be the focus of growth and innovation by the technology provider, but it’s considered good enough to sell and service. When the technology does not receive the investments needed for continuous operations and improvements, it will move to “Limited,” which means the system does not live up to expectations. Problems such as performance and stability issues go unaddressed, or there are huge delays to address them. Finally, “Obsolete” sounds like what it is: Your technology has been sunsetted by the provider. No further investment will be made, and the vendor plans to remove it from support and maintenance, regardless of your opinion on the matter.

FIGURE 9-2 As money spent to build and maintain cloud-based solutions increases, the obsolescence of non-cloud systems accelerates until risk and cost inflect for enterprises that chose to maintain more traditional systems in data centers.

Customers do not have much recourse, assuming the technology provider still follows standing agreements. Normally, the vendors will work with you in good faith to move to other systems, such as those based in the cloud, and perhaps provide migration services to make the transition. Hopefully, you’ll get a discount on the new cloud services, but this normally comes with a new set of agreements. A new cloud service-level agreement (SLA) will usually lean in the vendor’s favor, perhaps more than the agreements provided for traditional systems.

You should also note in Figure 9-2 that we’re dealing with two shifts. First, the rise of cloud spending, which shifts focus to other technologies in the marketplace. Second, the effect of the rise of cloud spending, which pushes the market to make an older technology obsolete.

This is nothing new. The technology market evolves. At the same time, we evolve the products that are being sold within these evolving markets. Again, the movement to PCs, smartphones, the Internet of Things, and other waves of technology are obvious examples of this phenomena. We just see a more obvious shift with the vast differences between traditional technology that ran within a data center and cloud-based technology with its very different consumption, billing, and value models. Clearly, it’s more noticeable. Enterprises are starting to worry about how cloud will affect their IT footprint.

Figure 9-3 depicts how this shift will likely affect the market. We’ll see more cost and risk from 2022 to 2023, and onward. The business need for traditional computing will diminish over time as more and better cloud computing alternatives become available. The value of traditional computing technology will drop much more significantly as a cost and risk gap widens for enterprises that leverage traditional technology.

FIGURE 9-3 The business need for traditional technology over cloud computing will diminish as fewer investments are made in traditional computing systems areas such as security and operations than are made in similar cloud technologies. This gap means that the cost and risk of technology quickly shift to those who chose to maintain traditional systems.

Can enterprises do anything about this shift? Not much. Some of you will feel the shift impact much more than others, depending on what core technology your business has in place, and the speed of the providers’ and your enterprise’s move to the cloud. The key here is to understand your technology provider’s sunset plans for your systems, or to recognize if your provider is on a path to be put out of business by the cloud or (more likely) absorbed into another technology company. Those last two possibilities are not great outcomes. You’ll have even less control of the technology you leverage today. It’s still better to have a plan in place that takes those possibilities under consideration. Yes, it will be a plan that makes some assumptions and calculates the path of least risk and cost for the enterprise, understanding that you might make some wrong guesses, and you’ll need contingency plans in place to get back on track.

More Consumption, but Prices Stay Static

Other issues seem to be artifacts of a changing market. For example, more enterprises now leverage public cloud providers, but the prices remain static. Yes, you can show me instances where prices have gone up or stayed the same or gone down, but it’s unlike the early days of cloud computing when prices fluctuated mostly downward to the point that it looked as though the public cloud providers were on a race to the bottom.

Figure 9-4 shows how cloud providers moved from a relatively new and innovative market where price cuts were more common to a point where the cost of development becomes more optimized, which is all in contrast to the early days when more innovation and inventions were needed along with low pricing to entice customers into cloud computing brand loyalty. The result is a market where service providers’ costs to develop and maintain cloud services continue to fall while enterprise IT organizations’ costs for specific services remain relatively the same. However, overall enterprise cloud costs continue to significantly rise through the increased use of cloud services.

FIGURE 9-4 Cloud providers are enjoying a relatively mature market with the cost of development relative to sales going down as time progresses and as the use of cloud-based resources continues to grow. However, per unit prices remain relatively the same for their customers.

Cloud providers explain this to me as passing on the cost of innovation from the market’s formative years back in 2008–2012. Much like the traditional software market, cloud profits appear in the later stages of the market when growth inflects, and the maturity of the services leads to better margins. At the same time, the relative cost of development and operations falls while market prices remain much the same.

Again, this behavior is something you see in most technology industries, where the entrance into the market produces loss leaders and there are limited or no profits. However, management speculates that current investments in innovation will reap future rewards when the market matures. That’s why I don’t often complain about higher provider profits now that cloud computing is a full-fledged technology market. By the way, there was risk that cloud computing would make a big splash and then come to nothing, which was also risk the providers had to manage.

I suspect there will be downward pressure on the price of cloud services going forward as some of the more common layers become somewhat commoditized, such as storage and compute. Also, the movement to multicloud and other higher layers of service that run across cloud providers will make it easier to switch between services, and thus put more competitive pressure on specific cloud providers that may have enjoyed a functional monopoly. For instance, some companies leveraged only one public cloud provider and were more of a “captive audience” when it came to their choices of cloud services. That’s no longer the case, perhaps for good economic reasons.

The Power of a Few Players

We also need to address the elephant in the room: A handful of public cloud players dominate about 90 percent of the market. This is not considered a monopoly because three major players compete against one another. But there were dozens of players in the early days of cloud computing. Some concerns arise that the big three will act as one when setting prices and gang up to drive upstart competitors out of the market. All these price fixing and collaboration activities are very illegal in most countries, so they are unlikely to make formal agreements or put plans in writing due to the penalties. But the potential is there. They could coordinate and control the market, and they will already control most of enterprise IT at that point. It’s a concern I’ve heard often from CIOs who must put their trust in public cloud providers. For now, let’s just hope it doesn’t happen.

Figure 9-5 depicts how the market has changed over the past 12–15 years. There were dozens of cloud provider upstarts in the marketplace when cloud began to form into its own market, typically around the rise of IaaS clouds. Basically, every telecom company, enterprise software company, and even hardware providers had public cloud and private cloud startups at the genesis of the market. Today we have only six to eight relevant public cloud providers. What happened to everyone else?

FIGURE 9-5 In the early days of cloud computing, there were dozens of public cloud providers started by telecom companies, software companies, and startups. Today, we’re dominated by just a few key public cloud players that needed to spend billions of dollars to provide services that enterprises would leverage. However, this does lead to just a few providers making up much of the public cloud market, which comes with its own set of concerns.

It became a matter of how much money could be spent by any given cloud provider. If you look at today’s major players, the top three had to invest billions to begin to capture significant market share. The larger players were the only companies in position to get to the scale and innovation level that cloud computing required to provide a viable public cloud platform. The companies without access to resources, or ones that did not have investors willing to take the risk, simply bowed out of the public cloud market and conceded defeat as they sought other ways to play in the cloud market. Some became managed services providers (MSPs), some focused on cloud networking, and many just focused on technology to work with cloud technology, such as operations and security.

For someone who had many of those companies as clients, both those able to build a significant public cloud provider or those that had to settle for second place, these were tough decisions. These decisions will likely need to be made again as we move on to other technological shifts, but they probably won’t be as significant as the shift to public cloud.

It’s interesting to note that there will surely be another evolution of public cloud upstarts that will try to enter the market. These will be cloud providers that serve a special purpose, such as focusing on a specific industry to create “industry clouds.” These clouds will provide services that are purpose-built for a specific vertical such as health care, retail, or finance.

They will stand up a public cloud to provide specific services that will most likely be mixed with the services from larger public cloud providers. Perhaps they’ll leverage multicloud deployments and/or use one of the existing mega clouds as their operations platform. We’ll have core storage and compute services from a major public cloud provider, but secondary industry-specific services from these industry clouds. There is a viable place in the market for providers that offer a limited number of services that work with public cloud providers to offer products that are custom-built for specific businesses. Of course, the larger cloud providers could enter this market as well, but they are unlikely to have the speed and agility of the smaller players.

Beyond industry clouds, the “micro-cloud” market has been evolved over the last several years as those aligned with larger public cloud providers seek to augment their core public cloud services and thus provide a viable and growing part of the services market. The likely evolution will be micro-clouds that stay away from areas that the larger providers will likely enter, which will be a common pattern as the cloud market becomes more saturated and existing cloud providers look for avenues of growth. Look for the growth of very innovative industry- and micro-clouds that can take public clouds to the next level by providing additive services.

This Is About Market Capture

Let’s go back to the competition between the larger cloud providers and how that competition will likely progress. While the market expands for public cloud services, there will be an aggressive dash to obtain as much of that emerging market as possible.

“Once a customer, always a customer.” That old marketing adage still holds true with cloud computing. Enterprises, organizations, and even specific systems are unlikely to change providers, although they may shift investments to other cloud providers, such as in the case of multicloud. However, after a system is coupled to a specific cloud provider, that marriage typically means a costly divorce. Captured market share remains durable for many years, which is why public cloud providers aggressively go after the same customers, basically selling many of the same cloud services.

Although one public cloud provider dominates the market right now, the overall market seems to be normalizing. Other cloud providers (including two of the top three) or the other second-tier players will accelerate their market share acquisition to gather a larger percentage of the market. Considering the rapid growth of cloud computing in general, most of the cloud players will experience rapid growth with some growing faster than the others. This process should continue as far as 2030, when we’ll see an equalization in the market for most of the major cloud players. A few of the smaller players will fall out, meaning they’ll be purchased by another larger player.

Yes, I hear all the antitrust concerns around cloud computing, and speculation about the likelihood that a single cloud provider will control the market. However, the most likely outcome will be 8–12 major cloud players, with 100 or fewer second-tier players (those that provide additive technologies such as security) with most of the market shares equalizing over time. That equalization will hurt some of the larger players that initially captured a large share of the market, but everyone will end up making a lot of money. The market will eventually be evenly distributed among the first- and second-tier players. I don’t think equalization will result in as much drama as most expect.

Why They Don’t Work and Play Well Together

Here’s a question I get a lot: Why don’t the major hyperscalers (large public cloud providers) work together to closely coordinate enterprise technology and platforms? The short answer is that there is nothing in it for them. They don’t run charities; they run massive businesses that depend on them to innovate and grow their businesses as rapidly as possible by using that innovation. As businesses, their objective is to return as much shareholder equity as possible. That means capturing more market share than the competition, and not sharing any secrets that will allow the competition to do something as fast as they can. Yes, there are some partnerships and coordinated standards activity, but don’t expect them to work together on your behalf when it’s contrary to their own.

Figure 9-6 depicts how this scenario plays out. Any major cloud provider will have their own set of business objectives (make money and capture market share). Because they want to capture the same market share, they work at odds, even though the goals of making money and creating value are very much the same. Therefore, you can’t count on any significant coordination to build common or other cross-cloud services, unless you can successfully present a mutually beneficial business case to the public cloud providers.

FIGURE 9-6 It should surprise no one that the major cloud providers operate with their own sets of objectives. They have no incentive to coordinate common services that could prove helpful to customers now that multicloud deployments are much more common.

What about the emerging multicloud market, where the game will shift to cross-cloud services? With a few exceptions, the larger cloud providers understand the shift to multicloud, but they do not plan strategic shifts of any significance to accommodate multicloud. When speaking at public cloud computing conferences sponsored by specific providers, I’m even “discouraged” from presenting multicloud topics because these topics conflict with their “existing messaging.” The bottom line is that they have yet to see multicloud as an opportunity, but it’s a clear risk to how they position and sell public cloud services. This situation will likely change as the market reality overcomes strategic shortsightedness.

Will Public Cloud Providers Become Like Video Streaming Services?

The comparison with streaming services is an apt one, given the way the market is evolving. Right now, most of the public cloud providers are building the same types of services that provide the same types of functionality. This compares to how you can stream The Office on several different streaming services with prices that range from free to $5.99 per episode. The version of The Office that streams on streaming service A versus streaming service B is the same, although the price, speed, clarity, and amount of advertising could vary (or not). Shows that exist on streaming services are one of the reasons people unsubscribed from cable and satellite services over the last few years.

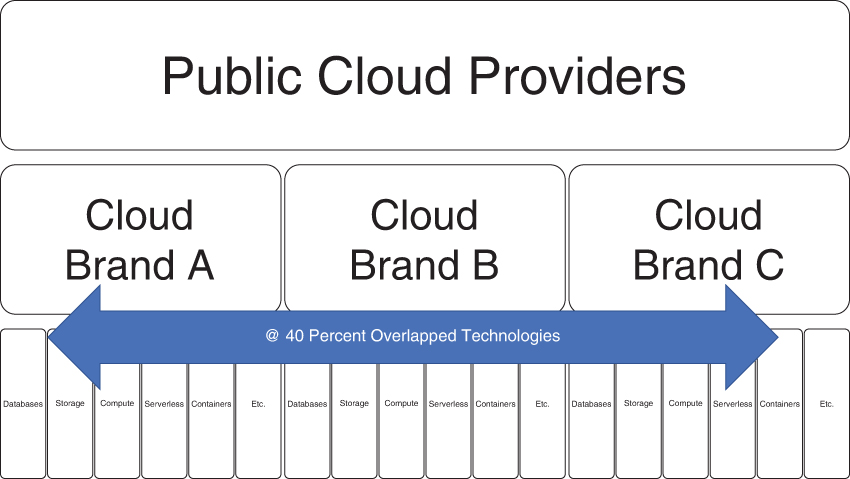

Of course, cloud providers will quickly point out that you cannot apples-and-oranges compare their services to shows on streaming services because their services are unique and provide better functionality than the same types of services running on their competitor’s cloud. It’s true; providers typically use different interfaces, APIs, security systems, operations systems, and so on, but they still provide overlapping functionality. Storage systems store stuff, processing systems process stuff. With a few native differences, it’s pretty much the same with public cloud computing resources; they provide the same functionality across many of the core public cloud services.

Figure 9-7 puts this functionality into perspective. Sets of overlapping technologies are very much the same from cloud provider to cloud provider (storage, compute, databases, containers, container orchestration, and so on). Major cloud providers offer their own versions of core cloud services such as object storage. However, many of the other services they offer are the same brands and technology, such as popular databases, application development platforms, and AI/ML.

FIGURE 9-7 Just as you can watch the same episode of a TV show on streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime, today’s public cloud providers offer overlapping services that provide the same or similar customer experiences.

If you think this sounds like commoditization, you’re right. Much of the evolution of cloud technology will be to solve the same solution patterns. Thus, you can purchase access to the same or similar technology from many different cloud providers. Of course, the public cloud providers continue to push back hard on this analogy by offering more innovative and unique services. Think about how services such as Disney +, HBO, Netflix, and many others create movies and content that aren’t available on other streaming services. However, they still offer “stock” content like the exact same classic TV series and movies that many other streaming services provide. In the case of cloud providers, their “stock” business has the same core resources such as storage, compute, and databases, which are the same or similar across cloud providers.

Next, we discuss how cloud providers supporting basically the same cloud services across cloud brands leads to some commoditization of the cloud computing market.

The Emergence of Commoditization

Commoditization is defined as the concept of products that have economic value and are distinguishable in terms of their attributes that become simple commodities in the eyes of the market or consumers, or something that’s common and thus has less value. Commoditization occurs in most markets as technology and products mature. If you think about flat-screen TVs, calculators, even hoverboards, they start their life cycles pricey and limited and then end up plentiful and cheap. This is how a product moves from limited use as it gathers market share and then moves into wide use where the market share is gathered and mature.

Cloud computing is not yet a commodity, but it’s moving from one side of the market to the other with some signs of its commoditization. One sign is that core cloud services are beginning to look alike on the major public cloud providers (hyperscalers). Also, they are selling many of the exact same cloud services such as branded databases, open-source systems such as Kubernetes, and popular AI systems that function the same across all cloud providers. These services are common, and thus they push the cloud providers into commodity territory.

So, cloud providers are made up of many things such as services (storage and compute) that are becoming a commodity, with some services that are unique with distinguishable attributes (virtual reality processing systems and edge computing simulations) that are proprietary to a single cloud provider and not found in all cloud providers. The more unique services that launch on a public cloud provider, the less likely they are to become commodities. My view is that we may see most of the cloud services become commodities, certainly the most used ones, while the many unique services are unlikely to commoditize anytime soon.

If that’s a bit confusing, you can think again about our streaming service example. Although they show much of the same content from streaming service to streaming service, there is content that only they provide, such as movies and shows that are made by the production companies that own the streaming services. Examples would be movies and series content that’s produced and owned by Netflix, HBO Max, Apple TV, Prime Video, Paramount Plus, Discovery+, Disney+, and many more. The content that they have in common is a commodity, whereas the content that only they own and stream is not. Their continued market ranks also depend on the quality of their unique content, which is also how we judge cloud providers, on the quality of their unique services.

Rise of the Supercloud or Metacloud

The rise of common cloud services is driving quicker commodification of cloud providers. Supercloud and metacloud are the most common names applied to the platform for these common services. Although we’ve already covered what common services are in the chapter on multicloud, it’s useful to look at how this trend is impacting the cloud market and how it will likely impact public cloud providers.

As you can see in Figure 9-8, cross-cloud services are services that logically exist above the public cloud providers. These services may run on specific cloud providers, but they exist logically and operate across all providers, such as those that are part of a multicloud. These services are best placed above all clouds, such as common security, operations, FinOps, and other services where it does not make good architectural sense to run redundant services; that is, each cloud should not run its own versions of services such as security and operations.

FIGURE 9-8 The rise of a common cloud known as a supercloud or metacloud means that the platform is moving to another layer of abstraction. More and more users will bypass the experiences of leveraging a specific cloud service and instead use abstract interfaces to interact with core cloud services.

As you can also see in Figure 9-8, we don’t go through specific public cloud interfaces and dashboards. Instead, we can go directly to cloud services that run on the public cloud platforms and bypass the cloud-branded services altogether. It does not matter if our database runs on any public cloud; we can leverage that database equally well on each platform. The public cloud platforms now provide less value because we treat them as a common host, and not as a single destination platform.

As you may have already figured out, as the supercloud/metacloud model becomes more widely adopted, it will put the commoditization of public cloud providers into hyperdrive. We will leverage cloud providers through layers of abstraction and automation. They will look pretty much the same through common interfaces and cross-cloud services that hide the specific features of a public cloud provider from the users and systems that access specific cloud services.

Our ability to deal with clouds using these common interfaces will allow us to deal with the resulting complexity of deployments such as multicloud. A by-product of the supercloud/metacloud model will be the commoditization of the cloud providers.

Likely Cost Shifts over Time

What could widespread adoption of a supercloud/metacloud model mean to our bottom line, considering that cloud is already more costly than most executives were originally told? Figure 9-9 shows the likely shift that we’ll see over time, with the current state showing most enterprises moving from single cloud deployments to multicloud. (See Chapter 6, “The Truths Behind Multicloud That Few Understand.”) The supercloud/metacloud model will rise from that point with cross-cloud services that will drive more commoditization, which should drive more price reductions, with this submarket of cloud computing taking three to seven years to mature.

FIGURE 9-9 The most likely shift we’ll see over time is the movement from single cloud to multicloud deployments. Then the focus will turn to building services that span public clouds, and then the cloud will morph into an abstract cross-cloud platform made up of many clouds and cloud services. The supercloud/metacloud model will become the new platform of choice for most enterprises. Although the final optimized state will take many years to accomplish, it’s important to understand the vision and the value of undertaking this journey.

Cross-cloud platforms will become de facto technology stacks of technology that will provide repeatable sets of services that support the rise of cross-cloud services. The underlying services will be largely commoditized, with the ability to leverage whichever service is the cheapest and best supports the functionality required for your project or application. When we get to this state of the market, the underlying cloud platforms won’t be as important to the users, but they will still be needed to support and provide the more primitive services such as storage and compute. You will find the differences between cross-cloud platforms and cross-cloud services in terms of how they are consumed.

The cross-cloud services emerging today are still being set up around unique business requirements, and the technology stacks are typically customized around the unique needs of a single problem domain. Cross-cloud platforms will provide many of the same services via the same technology that’s configurable for each problem domain, so you end up having the same platforms that are adaptable and do not need to be completely replaced. Cross-cloud platforms are science fiction at the time I’m writing this book, but they are bound to evolve at some point. We cover this topic in much greater detail in the next chapter.

The Emergence of System Repatriation

Another shift we’re likely to see, at least in the short term, is the repatriation of applications and data back to traditional on-premises systems. This, in response to rising cloud costs relative to traditional computing consumption models (for example, the data center). You will repatriate or repurchase hardware and software that you own and maintain, and resume responsibility for all the cost and risk involved in that model versus using public cloud providers.

Keep in mind the repatriation usually means returning to traditional systems after migrating them to a public cloud provider. But this shift also includes those who are considering migration to cloud and have not done so yet. Or those considering where net-new systems and databases will be built and deployed. You need to consider all use cases of traditional versus cloud-based platform selection.

Cost issues will drive most repatriation. As we covered in previous chapters, the cost of owning your own hardware fell substantially at the same time public cloud usage rose. This decrease went largely unnoticed as cloud computing innovations took center stage in the technology press. However, it makes a lot of economic sense to run certain data storage and application processing on traditionally owned hardware platforms. Right now, this option is often overlooked.

As you can see in Figure 9-10, enterprise cloud costs remain fairly static although many clouds’ ongoing costs are well above what enterprises expected, which in turn drives interest in repatriation. At the same time, hardware costs such as hard disk storage and compute that you purchase and host yourself have fallen significantly. The interest in repatriation will become significant as enterprise IT looks for more bang for the buck.

FIGURE 9-10 What drives interest in system repatriation from public cloud platforms? The cost of hardware and hardware maintenance experienced a significant drop, as we covered in Chapter 2, “The Realities and Opportunities of Cloud-Based Storage Services….” As the prices dropped, the cost of cloud computing remained pretty much the same per system. The shift to owned or managed platforms will likely occur for cost reasons.

Why Organizations Move to a Hybrid Model

Although most enterprises are not giving up on cloud computing, some are making economic decisions to run applications and store data in the most cost-effective spaces that might not be in the cloud. Again, cloud costs are typically much higher than many enterprises expected, and the huge potential cost savings of cloud computing have not yet materialized for most organizations. Many executives now understand that the lion’s share of net-new and innovative development is done for cloud platforms these days, and yet they still decide to take a hybrid approach. They decide to put some data and applications on public cloud providers, and other data and applications in enterprises data centers.

These days it’s almost impossible to run your entire application portfolio and store data on traditional systems without suffering from an inability to participate in cloud-focused technology such as business analytics, AI, and serverless computing. But all applications and all data stores may not need or even use that technology, and thus it makes more sense to take advantage of rock-bottom hardware prices and keep some applications and data stores on more traditional platforms. There is not an either/or model here; we’re not giving up cloud computing to go to enterprise data centers. We do both to find the most cost-optimized platforms.

Why You Need to Justify the Move to Cloud as a Business Value

Too often the hype leads the decision-making process. Cloud architects and IT architects in general need to keep an open mind when it comes to what platforms to pick. You need to justify any platform by the business value it can provide, cloud or not. The drive to move everything to cloud-based platforms could mean you don’t leverage the most cost-optimized platforms. I’ve seen too many projects shift to cloud computing platforms to do uncomplicated tasks such as data storage and simple application processing that resulted in the enterprise spending six to seven figures more per year on cloud-based resources versus the cost of resources leveraged from an existing enterprise data center, with all factors considered.

The core message here? No matter how the cloud market progresses, you must consider all options, old and new. Remember, innovations now take place on the public cloud platforms, so there’s a certain need to take advantage of those upgrades and modernization. However, for a substantial amount of time, more traditional solutions could prove much more cost-effective. It doesn’t matter if you’ve moved to a public cloud and need to move back to save money, or if you’re looking to migrate to a public cloud provider or build net-new systems and databases, all solutions should be considered in terms of their ability to return value back to the business.

The Rise of Federated Cloud Applications and Data

Another shift in the market is the anticipated rise of the federated cloud. A federated cloud contains a logical application(s) and logical database(s) that span public cloud providers, and sometimes legacy and edge-based systems as well. An example of federated cloud applications and data is depicted in Figure 9-11. However, they are typically more complex than that in real life, where we have common services that support cross-cloud functions such as operations, security, and FinOps that run on some physical cloud, or even within a traditional data center, but they logically exist cross-cloud. What’s more unique is a set of federated applications and coupled data that runs across various cloud providers as well.

FIGURE 9-11 Federated applications and data mean that we can deploy applications and data using any number of mechanisms, such as containers, on an intra- or inter-cloud platform. This allows us to mix and match the right parts of the cloud-based application to the right cloud platform, such as one cloud platform having a superior AI system and another a better database. Of course, there will be common services as well, such as operations, security, and FinOps.

For example, let’s say we’re dealing with customer data that physically exists on three different cloud providers’ databases. We have customer sales data running on one public cloud provider, customer shipping data that runs on a sales order entry system that exists on another public cloud provider, and finally a set of inventory shipping data that resides on yet another public cloud provider. We need to access all that data in such a way that a single application does not have to deal with three different cloud native database interfaces. Thus, we leverage some technical tricks such as database virtualization. This trick provides a layer of software between the three different cloud native databases and the applications or humans that need to access that data. Of course, we could relocate the data to a single database so that all the data would physically reside on a single cloud provider. However, that is not cost efficient in this example, especially because the data serves other purposes on each cloud provider, which is common in most cases. Therefore, we employ database federation within a federated cloud to deal with the data where it exists and use mechanisms to remove the complexity of dealing with many different data stores using the terms of that data store. We end up making our own terms, and the databases accommodate us.

We’re just dealing with data in the preceding example. Other things that can be federated include AI systems, container orchestration, business analytics, and any other technology that may work best on one cloud provider over another. Of course, we need common services as well as those depicted in Figure 9-11. These services provide things like security, operations, and FinOps across all cloud providers, and thus across all federated applications and data. We federate these services so we don’t need to deploy redundant systems (like security) on each and every cloud provider. This approach makes the federated architecture less complex and more cost-effective to operate.

We typically partition the application around functions, or where specific types of services (such as containers) run on one cloud. This may be done for many logical reasons, but the specific cloud may provide the best platform for containers, while another is better for data, and a third is better for high-speed transactions. We would also run the data on a cloud provider that provides the best platform to maintain data. Basically, we would mix and match cloud providers to host parts of the application each hosts best, with those parts of the application distributed among the cloud providers.

The market will likely move in the federated direction for a few core reasons:

The ability to leverage specific cloud providers for specific application attributes that will provide the most cost-effective approach to run each part of the application.

The use of abstraction and automation to remove the developers and operators from the underlying complexity of leveraging many different cloud providers as hosts for those services.

The use of cross-cloud services to provide common operational and security services that span a federated architecture. Thus, it’s functionally treated as a single architecture and platform.

The ability to support resilience using redundancy that’s built into these federated systems, which means a single failure is unlikely to take down the entire federated application.

Figure 9-12 depicts another view of how we deal with federated applications that span more than a single cloud. In this example, we’re dealing with two layers of services: The application services or APIs, and the native cloud services that are specific to the public cloud platforms. Each provides its own set of functions with the application services and/or APIs that interact with the application and are part of the application. An example would be an application service that’s written to request that a credit check be done. This becomes a common application service that can be called many times, but from different components of the application.

FIGURE 9-12 Federated applications deal with two layers of services: services such as database and AI that are leveraged by the applications, and services that are leveraged by core services such as storage and compute.

Federated applications can also access the cloud platform services, or services that are native to specific cloud platforms such as databases, storage, and compute services. Taking our credit check example, we would need to leverage data access that typically occurs on a database that’s native to a specific cloud provider to gather the data required to provide the credit check, which is the application-specific service. These services work together to carry out the needs of an application with the application services and/or API that span across cloud providers, and those services leverage the native services of whatever cloud provider is needed to carry out a platform service such as data storage and retrieval.

The downside of federation is the main reason we don’t see it much today, as depicted in Figure 9-13. This figure shows an actual design of a federated system built on a multicloud that was designed to run across cloud providers, legacy systems, and a private cloud. Note the applications at the top of this stack, the number and layers of services that are needed to support the federation, and the use of core resources such as storage and compute that exist at the lower-level platforms (legacy, cloud, and private cloud). Also, the services on the right side provide governance, security, operations, and so on, that must span all layers, including abstractions, data integration, and orchestration.

FIGURE 9-13 Headed for complexity? This is what systems are evolving into right now, with some of them already in existence. With the progression of distributed development, the number and types of services that applications need will only expand. Moreover, we’re moving to ubiquitous platforms where the types, locations, and ownership of the platforms make little difference in terms of how enterprises will leverage systems and common core services.

Now we have to face the reality that this federation will lead to complexity. As we discussed in Chapter 6 on multicloud, complexity must be managed and mediated. We’ll need to reduce the number of boxes and items shown in Figure 9-13 to create common services that can span services up and down this stack as well as side to side. Creating such services will be the mission of the cloud computing industry as it matures and finds new ways to make itself more useful and cost effective.

Clearly, the need to run systems across cloud providers will be the ultimate solution that most enterprises seek, with the ability to mix and match what’s needed from each provider. The problem is that most enterprises don’t have the know-how and/or the tools to deal with today’s complexity, much less tomorrow’s complexity issues. This evolution will be long, but, when done right, the end results will provide more business value and better and more optimized use of technology.

Traditional Systems Remain…Why?

Each month I’m asked when legacy or traditional systems will go away. The short answer is, “They won’t.” Although we’ll see a diminished interest in older legacy systems and even more modern legacy systems such as Intel-based development using LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, Python), all types of legacy systems will hang around for a specific reason: They will prove too costly to migrate to cloud-based systems. Better put, a business case cannot be made to remove them from a physical data center and put them on some cloud provider.

There will come a point when we’ve migrated as many systems to the cloud as we can that made economic sense to migrate. Although we won’t hit this milestone anytime soon, what will remain are legacy systems that don’t have good pathways to get them to cloud…although enough time and money can accomplish anything.

The core hindrance to moving most of these systems will be the numbers. Let’s say it costs $2,000 per month to maintain certain applications in the data center space using all-in costs that include power, humans, and networking. However, it costs $.5 million to migrate those systems to a public cloud provider, and another $3,000 per month on cloud service fees to operate them. What would you do?

Figure 9-14 depicts how this scenario will likely play out. We’ll hit a saturation point at what I suspect will land between the 70–80 percent mark for applications and data that are migrating to the cloud, which means that 20–30 percent of applications and data won’t move to the cloud. The reason is not that we can’t migrate them, but that it does not pay to migrate them.

FIGURE 9-14 Most enterprises will find that about 20–30 percent of their systems are not economically viable to move to “the cloud.” This means they will hit a saturation point, and these legacy systems will likely remain where they are or move to other viable options such as co-location providers or managed services vendors. Given the issues we’ve discussed around holding onto legacy systems and the applications that reside on them, enterprises will have some trade-offs to think about.

Many will argue that enterprises need to get rid of their owned data centers, and I agree with that viewpoint…to a certain extent. There are more cost-effective alternatives available, including managed services vendors that provide platform analytics for most traditional systems as well as cloud access. Also, co-location (co-lo) providers that offer data center space for rent. I suspect we’ll see an inflection point in this market as well, as many enterprises see the writing on the wall when it comes to some of their older and more traditional applications.

I do not mean that these legacy applications will never move. We’re putting stuff on public clouds that I did not think possible just a few years ago, and it will make sense that cloud providers will accommodate this part of the market at some point. However, they will do the same math when it comes to what enterprises would like to move versus what it pays to move. It all comes down to finding the best business value, and for that, we’ll leave 20–30 percent of those traditional applications behind for good reasons.

Battle for Human Talent

Finally, let’s get into a non-cloud topic that’s rapidly becoming the most limiting aspect of cloud computing for most enterprises. I’m talking about your ability to hire the right people to deal with cloud computing, including those with skill sets in migration, operations, FinOps, security, and other things that need to be done right the first time.

Figure 9-15 shows what we see today and what we saw in the past, in terms of available cloud skills. The demand for cloud skills grew at a steady pace for the past 15 years but accelerated over the last 3–5 years. What drove this skills shortage? The rise of cloud use in general, existing systems aging out, and worldwide events such as the COVID-19 pandemic that accelerated the move to the relative safety of public clouds, and the subsequent need to support a distributed remote workforce. The demand for skills outpaced the supply, with not enough skilled cloud professionals entering the workforce to meet the demand.

FIGURE 9-15 It’s no secret that demand for cloud skills outpaced supply by a wide margin. This margin is what holds up cloud development and migration progress. Many enterprises feel forced to hire less qualified talent who make mistakes large and small as they acquire their cloud skills on-the-job. These mistakes and missteps can and often do cost a substantial amount of time and money to fix, and they incur a great deal of risk.

The cloud skills shortage resulted in higher risk, higher costs, and project delays for both enterprises and consulting firms as they tried to make do with whatever talent they could find. Working with less skilled talent often delays or cancels cloud computing migration projects or reduces expectations as to what enterprises can operate on the cloud, and the types of technology they can employ. In more general terms, it’s slowing things down. In many instances, enterprises are hiring below qualifications, and major mistakes are being made with ill-conceived cloud solutions that must be fixed at some point. Yes, this is a bad. What can you do about it?

What to Exploit Right Now

It’s hard to buy the right talent in a seller’s market. There are no foolproof ways to eliminate this problem, but there are ways to better manage it. Compounding the problem, colleges and universities are not producing the number of qualified candidates needed to fill even the entry-level job openings. Although you should have a relationship with and pipelines to traditional learning institutes, a better option would be to hire in less traditional and more innovative ways. I’m often taken aback by the number of enterprises that still rely on college degrees to determine who should be considered for cloud jobs or not.

The dirty little secret about cloud computing skills is that you don’t need a computer science degree from an Ivy League university to gain access to some hot public cloud computing skills. Those skills can be acquired in many other places with almost no limitations on access. For myself, I don’t require a college degree for someone to work my cloud jobs. However, new hires must have the desired skills to quickly provide productive value and, more importantly, the willingness to be a continuous learner. You’re not much good to me if you don’t want to update your own skills as you go versus me requiring that you attend mandatory training to keep your skills up to date.

So, I work with learning services and even community colleges that focus on providing core cloud skills but lack requirements for nonrelated courses. Thus, you get somebody who other hiring organizations may avoid because they don’t have a college degree, but they turn out to be a superior hire because you want them to play a single role, such as cloud security, cloud development, or cloud databases, and you encourage them to build their own career from there.

Other people to consider include those who are reentering the workforce after a long span of raising families or other life events. They may have had some computer experience in the past, but they don’t have current skills such as cloud computing. I’ve worked within programs that have provided training free of charge for those who are looking to reenter the workforce with more modern skills (such as cloud computing). These individuals are often successful because they already understand the basics of computing and often make an easy transition to cloud computing. Moreover, they tend to be more motivated with a stronger drive to learn. Women are most of the job candidates here—again, a group often overlooked by the traditional hiring organizations.

My success in hiring the right cloud skills is largely due to looking where others do not and being more pragmatic about assessing a potential employee’s near-term usefulness as well as their long-term ability to grow as a teammate and not just an employee. Yes, I’m often criticized for this approach to hiring. Some point out that I won’t get employees with more rounded skill sets. So far, that hasn’t been my experience. Good people are good people, no matter where you find them.

The Secrets of Keeping Cloud Talent

Let’s say you manage to hire the cloud staff you need. With all the competition and opportunities out there for cloud talent, how do you keep them? Incentives sometimes work, but the best approach is to foster a culture that keeps and attracts the right talent.

The first thing you need to understand is what motivates people. Why do they stay or leave jobs? Surveys are often done to determine the reasons, but often they miss what employees don’t tell surveys or tell their former employers, or what they may not understand themselves. Complaints might focus on their pay, or the lack of parking, or even the need to adhere to a strict expense account. Even with those issues fixed, they still leave. What are we missing?

Figure 9-16 shows a good framework to understand what talent may expect; again, in many instances they may not have externalized any of these expectations. Early in my career, I was “encouraged” to address the results of employee surveys, to fix issues that showed up in the surveys, and the enterprise still experienced huge turnover. After watching the same scenario play out in many peer organizations, I went with my gut to address what I felt needed to be fixed to create a positive work environment. Turnover dropped significantly, while hiring through word of mouth increased. Figure 9-16 depicts a simplistic representation of basic employee expectations, but it’s a good example to start with. Working from the top down, we can look at trends in “give-a-damn” about certain aspects of work, starting with income. Almost everyone thinks that they’re underpaid, so they want more money. That’s a no-brainer. However, money is not always as important as you might think, with considerations for income trending slightly up over the last five years. Yes, they still want more money, but other aspects of their jobs have equal or more importance, even if they don’t say so out loud.

FIGURE 9-16 The secret to hiring and keeping talented people with solid cloud computing skills is to understand their underlying motivations. Surprisingly, it’s not like the old days when companies that could pay the most or offer the most perks retained the best talent. Today, most skilled staff want fair compensation with new challenges and experiences that make the job interesting. Many want a flexible work environment where they can live and work anywhere in the world. Are you ready to meet those expectations?

Working down from there, the opportunity to gain more or better technical experiences is what many IT- and cloud-focused employees seek. They are in the technology sector because they find it interesting. Their ability to gain on-the-job experience with more current and exciting technology is often a motivator for people to remain in a cloud job. The lack of new technical experiences is a reason many people cite when they leave cloud jobs.

Lifestyle is rarely considered a significant employee expectation. This does not mean that the cool cloud team leader has a gaming console in the office, but it’s important to understand that everyone has different expectations of what they want to do and the life that they want to live. Which naturally leads to location/remote work.

The best lifestyle and location assets are not assets at all, but flexibility around working hours, work location, and the resources to support these nontraditional types of work lifestyles. I often say to employees, “You can work anywhere in the world and keep any hours you like, as long as you meet the agreed-upon expectations. Find your best path.” On the other hand, some people like structure and the ability to work in an office environment. They should be accommodated as well, even if it’s a nontraditional setting such as coworking office spaces.

Few cloud people resign due to the lack of promotional opportunities. More than once I’ve promoted someone and they soon quit anyway, so the promotion was not the motivator. Most enterprises have a flat organizational structure these days. Those who need to look at an org chart to determine their value are perhaps the people you don’t want on your team. While people do want to get recognized for their work, they don’t care as much about where they sit in the hierarchy as they did a few years ago.

Finally, access to training. While you should provide access to training, it’s not productive to have mandatory training. You need to let everyone know that training is available, and you’ll be paid while you take the approved training courses. For those who want to get better at their jobs, it’s desirable to further their education. Keep in mind that people learn in different ways. Some are good at classroom learning; others need to learn by doing. Don’t put too much emphasis on certificates and other traditional ways to prove that they completed a certain set of steps that makes them an “expert” on a job description.

There are many (including myself) who learn best through doing, and they don’t provide certificates for that kind of knowledge. “Hands-on” knowledge is the type of experience most enterprises want or need, although almost all insist that qualified candidates possess a coursework degree of some sort and/or a certain amount of on-the-job experience. But few people have substantial amounts of on-the-job cloud experience. See the Catch-22 here?

Someone once said, “You go to college to get the piece of paper that gets you the job. Then you learn how to do the job.” There are fields that still require degrees or certifications or internships of various sorts to prove you’re capable of doing the job. You don’t want a surgeon, lawyer, or electrician to purchase the tools of their trade one day and open for business the next.

Many IT jobs are the same, with degrees and certificates that prove someone knows enough about the job to not fall flat on their face on day one. However, at this point in the cloud skills shortage life cycle, an equally important skill is that of a hiring executive who’s good at identifying potential cloud talent. Many of today’s hires with the potential to be good or even great future cloud employees are found outside the degree/certificate/internship mills. Be open to the possibilities.

Call to Action

Out of all these chapters, this one was the most difficult to write. Not because the topic of the cloud market is that complex; it’s that it requires me to speculate about where it’s moving. Yes, this is an educated prediction in some instances, but so far my predictions track record is pretty good. Other trends are obvious to anyone who watches the cloud computing market.

If you’re reading this chapter, chances are good that you’ll be called on at some point to make predictions and plan where to invest your enterprise’s time and money. This important chapter gives you the inside story as to how this all plays out. The calls I make are based on what I’ve seen play out in the past, and on what I see happening today. I’ve tried to be as open and as honest as possible. My prediction is that my predictions will be about 95 percent correct, but you tell me.