CHAPTER 1

THE RIGHT PEOPLE AND THE RIGHT TIME

The orchestra was warming up and preparing for the season's last concert. I always liked the chaos of sound as people warmed up their instruments and practiced those passages and runs one last time before the performance. Mixed into the cacophony of musical instruments were the conversations of the audience. People caught up with old friends, talking about their lives and children. Some discussed their jobs or where they planned to go after the concert. Others sat silently, reading the conductor's notes about the evening's performance, including the history of the pieces and the composers who wrote them.

It was a time of building anticipation until the moment the concertmaster rose from their seat, and the orchestra and audience become silent, waiting for the first oboist to play their perfect tone for the rest of the orchestra to match. The lights dimmed, and the conductor waited a couple of moments before stepping out into the stage lights. He took a couple of deep breaths and wiped the sweat from his brow as he listened for his heartbeat. This beat would be his guide for crossing the stage to his podium. It was his baseline for the downbeat and every subsequent beat that came after.

All of this was happening as I flipped through my music, making sure it was in order. I rosined my bow and checked that the peg was secure on the floor at my feet. The point had found its groove so that my instrument didn't slide from my hands during the performance.

My mind should have been focused on the music and only the music, but I was distracted. I had just been notified at the afternoon's dress rehearsal that I had been selected as the new orchestra manager. Up to the moment I heard, I didn't really feel I had a chance. I had been in the symphony for 20 years, and so I had the experience as a musician, and I had been on the orchestra committee, a group that spoke for the needs and wants of the symphony members. However, I wasn't sure that qualified me to be the orchestra manager. It was a paid position with specific responsibilities, and this coming year, of all years, was going to be challenging.

I thought of a number of other symphony members who would have been qualified, or they could have been hired outside the symphony. The hiring committee decided that I was their first choice, not only because of my experience as a musician but because I had a few ideas of changes I wanted to implement in the coming year.

“We're so excited you are the new orchestra manager, Jerry,” said Cindy Wittaker, the first bassoonist. “We loved your ideas about direct deposit for the musicians and upgrading our music distribution.”

“Thanks,” I replied. I had a heavy feeling in my stomach. “I'm really shocked you chose me, but I hope to do my best.”

“We know you'll do great,” replied Cindy.

I thought about all I needed to do before the next season. The next season was the 100th anniversary of the symphony. No pressure at all. I had not seen the program layout for the season yet, but knowing our maestro, it was going to be over the top, not only musically but logistically. The maestro loved large pieces with many musicians, and the symphony often had to rent instruments and hire extra musicians. I was sure this coming season would be no exception.

Unfortunately, there wasn't any list of musicians to be passed on to me from the previous manager. I needed to create a database from scratch and add musicians as substitutes for concerts throughout the year. In addition, I needed to set up auditions for vacant contracted musicians for the following year as well. The summer was going to be a busy time, and I only hoped I had the skills needed to put it all together.

One of the difficult parts of hiring musicians as substitutes is that I would hire them sight unseen or, in this case, sound unheard. I would have to get recommendations from other musicians for people to call. In some cases, I would call people the day before the first rehearsal if someone called in sick. How would I determine that they had the chops to play and that they were reliable enough to show up on time and be prepared? If the musician didn't show up or wasn't symphony caliber, I would be the one to answer for it, so I needed to figure it out – and fast.

The maestro stepped onto the stage, and there was thunderous applause. The maestro held a hand to us to acknowledge us, and we stood. Well, at least those seated stood. The bass section was already standing.

I mentally pushed all the distractions from my mind. It was time to be focused on the music and worry about managing later. The maestro raised his baton, and I prepared my bow for the first downbeat of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. The baton lowered, and we were off to another magical live music experience, sure to have the patrons chattering for days to come.

* * *

At intermission, my wife approached me with that look I had learned to dread.

“I just heard from Sally that you got the position as orchestra manager,” Laura said. “Why didn't you tell me?”

“Well, I just found out this afternoon,” I replied. “I had to grab a quick sandwich and change before the concert. I'm sorry that I didn't have time to talk to you about it.”

“We talked about this, Jerry. I didn't think it was a good idea because the pay is low, and you don't have the time.”

As I remembered the conversation, it was Laura who told me it was not a good idea. The symphony provided me with such a wonderful opportunity to perform and express my creative talents that when someone nominated me for the position, I was honored.

“But I do have time,” I responded. “This would actually supplement my income, not take away from it.”

“What experience do you have managing a symphony? You are a musician, not a business person.”

She had a point there, but I had not had time to process what I needed to do to make up for my shortfall of experience.

“Can we talk about this after the concert? I need to get back on the stage.”

“Can you turn down the position?” she asked. She wasn't letting it go.

“I suppose I could, but I really don't want to. I really need to get on stage,” I pleaded.

Laura crossed her arms and snapped, “Fine.”

The most technical part of the concert was in the second half, and now I had my wife to contend with in addition to the pressure of figuring out what I needed to do as the orchestral manager. The orchestra members returned to their seats, just as they had at the beginning of the concert; they rosined their bows, warmed their instruments, and practiced tricky passages one last time before the performance.

As the maestro took his position on the podium, a thought occurred to me. In college, I had taken some business classes, and there was a teacher, Carl Richardson, who had left an impression on me. In college, my focus had been on music performance and education, but I really got a lot out of his classes. He might be able to give me some advice on how I would manage the orchestra and all of the things I needed to accomplish this year. I made a mental note as the maestro raised his arms, ready to give the orchestra their downbeat. All eyes were locked on him, and everyone was holding their breath, including the audience.

The baton in his hand reached upwards and then down, and the orchestra began to play. It was amazing how much control the conductor had over the orchestra. He decided the tempos and the volume; he gave people cues on when to come in. All of this was accomplished with his hands, arms, facial expressions, eye contact, and even his posture. He managed the music, and I thought as the music flowed before my eyes that I needed to be a conductor in my own right as the orchestra manager.

* * *

The next day, I met with my old professor, Dr. Richardson.

“I am so glad you could squeeze a lunch in with me,” I said. “I am just a little overwhelmed with this new position I have, and I remembered you taught me about managing projects. I took notes, I promise; I just never knew I would need them.”

“I'm always glad to help out a former student,” Dr. Richardson replied as he sipped his tea. “So you have plunged into the world of portfolio management.”

“Well, I got a position as the orchestra manager, although now I'm not sure it was the smartest move.”

“How so?”

“I'm overwhelmed. I have so much to do, and there are these timelines I have to do them in. The former orchestra manager quit the symphony, so I feel like I'm starting from scratch. Why did you say portfolio management?” I asked.

“Because, from what you described, that is exactly what you're doing. Think of it like your concerts. You have this program you're performing. In that program are pieces of music you're going to play. And each of the pieces requires certain musicians to play them. You following me?”

I pulled out a small notebook and began taking notes. “Yes, go on.”

“Each of those are projects that you have to manage. The choice of the program. The choice of the music and then getting that music. Picking and hiring musicians. All of those are parts of portfolio management.”

“Okay, I get you so far.”

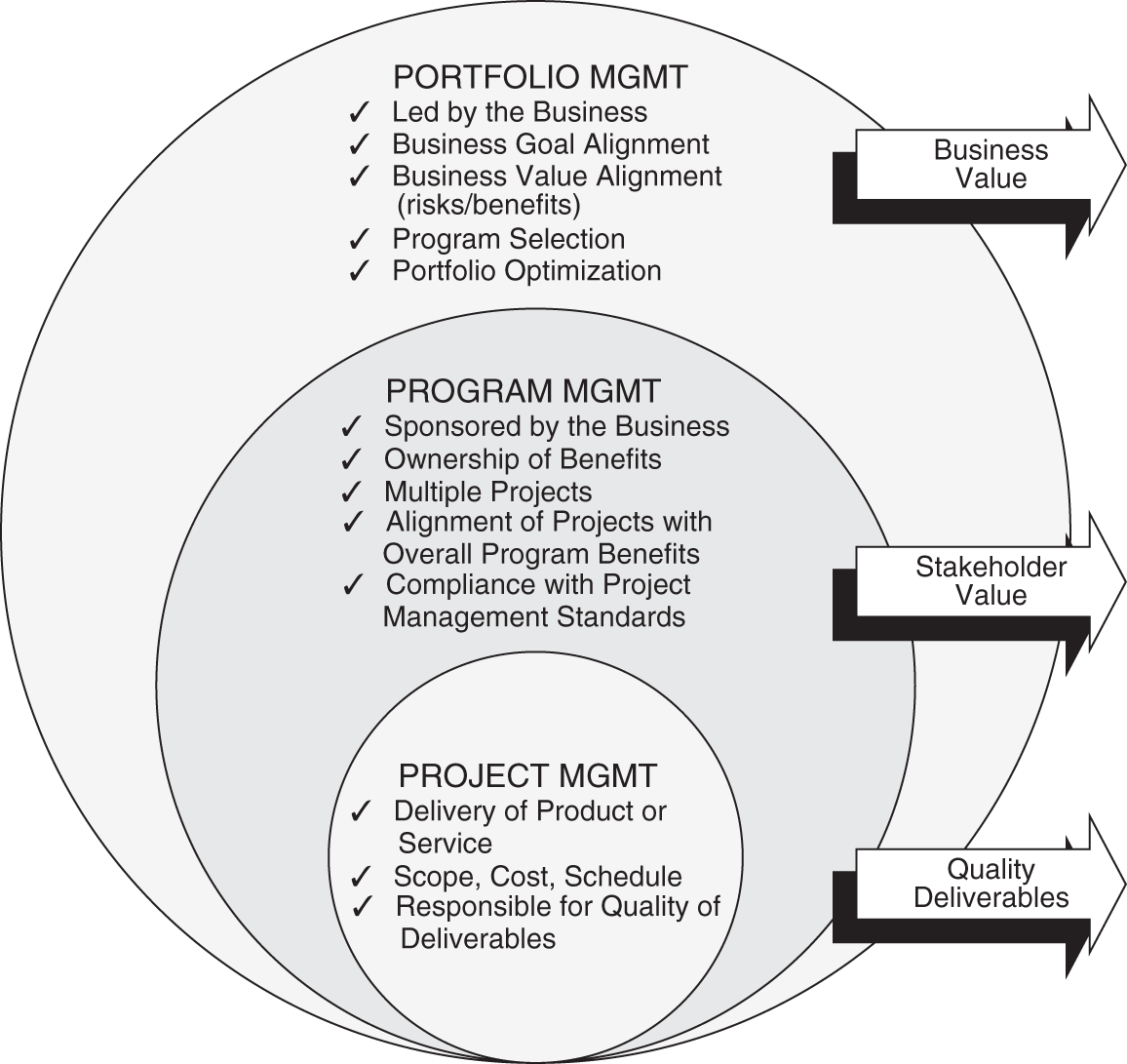

“Here's a diagram for you to keep that helps demonstrate the different levels of PPM,” said Dr. Richardson as he passed a piece of paper to me. (See Figure 1.1.)

“As you see, there are three levels, and you will be involved in each of them.

“Let's start off at the highest level, the portfolio management circle. Here you'll be dealing with the higher parts of the organization. In your case, it would be the board of directors, the orchestra conductor, the director of the symphony, and so on. You'll discuss the season, the programs, and any other project you'll be doing with the symphony. Do you have new things you want to implement?”

Figure 1.1 What's the difference between PPM, PgM, and PM?

“I do want to fix the way the musicians get paid. Right now, it takes two signatures, and sometimes musicians have to wait for their checks to arrive in the mail. It's a real pain.”

“So, at the portfolio management level, you might propose your changes and how you plan to roll them out.”

“I want the symphony to move to direct deposit so musicians can get paid on the date of the concert.”

“Great, so once you propose that project and get it approved, you would move down to the next level of program management. You would have the blessing of the director and board to implement this new program, and you would then share that with the musicians. You would explain how that process would go and what you needed from them to make it happen. You would make sure that there was a connection between the musicians and the payroll.”

“Okay, I'm following you so far,” I admitted. Some of the pressure was beginning to release from my shoulders.

“Then this is followed by the project management level. This is where the magic happens. You're responsible for the deliverables and making sure everything works as it's supposed to. The musicians play the concert, and they have their money by the end of the day. You'll continue at this level for each concert, making sure the process goes smoothly, and you'll have to onboard new musicians into the system as they're hired.”

“That totally makes sense,” I said as I fastidiously made notes.

“That's just one project. As the orchestra manager, you'll be handling multiple projects at once.”

“I know; that's what's overwhelming me,” I admitted.

“You need to take time and prioritize. What projects need to be done first? Once you've done that, you need to figure out at what level you'll be beginning. If it's not a new project but is one being handed to you to manage, then you may not need to begin at the portfolio level. Instead, you'd be at the program level and figure out what you need to know, have in place, and what resources you'll need. Then you can move to the project management level. Right now, it sounds like you have both new projects and ongoing projects you want to implement. My advice is to write each of them down, figure out a rough timeline for them, and begin figuring out what you'll need to begin managing them.”

I sipped my coffee. Perhaps I needed a spreadsheet, or maybe I could use some software to do it.

“Is there some sort of software I can use to manage all of this?” I asked.

“Yes, there are all sorts of programs you could use,” Dr. Richardson replied. “But first, I think you need to dive deeper into what are the best practices of portfolio management. This will help you tremendously moving forward.”

“Are there books or articles you might recommend?” I asked.

“Sure, here are a few articles and books that a friend of mine, Gerald, who's an expert in project portfolio management, shared with me.”

- What is the difference between projects, programs, and portfolios? https://www.pmworld360.com/what-is-the-difference-between-projects-programs-and-portfolios/

- 5 Secrets of strategic growth using portfolio management principles https://www.pmworld360.com/5-secrets-of-strategic-growth-using-portfolio-management-principles/

- 5 Steps for managing unrealistic expectations https://www.pmworld360.com/5-steps-for-managing-unrealistic-expectations/

- Culture Is the Bass: 7 Steps to Creating High Performing Teams https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07YMP3Q2Z

- Strategic Leadership of Portfolio and Project Management: Bridging the Gaps Between Setting and Executing Strategy https://www.businessexpertpress.com/books/strategic-leadership-portfolio-and-project-management/

“He also has an online program. You can complete it on your own time, and it can really help you. I wish I had more time to give you as you learn this process, but I'm swamped right now. You could take some classes on it, but I would assume an online program would be better for your budget and your time.”

“Yes, it would,” I agreed.

You can find the online program here, Ascending to the APEX of the Project Management Ladder: Demystifying Project Portfolio Management and Building a Winning Game Plan for Becoming a PPM Expert: https://geraldjleonard.teachable.com/p/the-apex-of-project-management

“I can be a resource as you have questions or need a little guidance,” Dr. Richardson added.

“That would be fantastic. How about I pay you in some comp tickets for you and your wife this coming season?”

“That would be outstanding,” Dr. Richardson replied.

Dr. Richardson's Tips

- Identify ideal candidates to manage the organization's project portfolio.

- Understand the difference between project, program, and portfolio management.

- Consider the value portfolio management can deliver to your organization.

- “But first, you need to dive deeper into the best practices of portfolio management. This will help you tremendously moving forward.”