CHAPTER 5

CHOOSING YOUR STRATEGY

“RJ,” I said frantically, looking through the symphony library for Beethoven's Third Symphony. “Where are all the string parts?”

As the music librarian, RJ was in charge of music parts for the symphony members. Some of the pieces the symphony played were ones they owned and were available in the library. Other pieces had to be rented, and when there was a new piece, he received the parts in the mail from the composers. He had to make sure each musician received their music in time to begin practicing their parts prior to the first rehearsal.

Two weeks was the standard, but in the past couple of years, parts were missing or were not handed out until the first rehearsal. I had witnessed Fernando throwing a baton at RJ when he realized that none of the cello section had their parts.

“Well, that's a piece we own, but the parts have gone missing through the years,” he said. “Musicians don't return them after the concert, or they lose their part and I have to scramble to get them a copy.”

This was a chaotic system that wasn't working. I had proposed a more digital approach, but it seemed to have landed on deaf ears.

“We need the parts to send to musicians to have for the audition packets. I'm not even going to mail them,” I said. “I just need them to scan and then email them and have a few copies available at the symphony office if someone wants to pick them up.”

RJ was flipping through torn envelopes and folders to look for the parts. He was one of the first‐chair violins, and we had known each other a long time. We both answered to Sam, but I was in a new position as the personnel manager. RJ and I would need to create a system that worked for both of us.

“Did you get my email about scanning all the music and sending that to the musicians?” I asked.

“Yeah, I don't know …” RJ began. “A lot of the musicians don't have printers and aren't very tech‐savvy.”

“But it would save the symphony time and money,” I said. “Mailing out music is becoming expensive, and emails are free. As you said, we're losing music, and I imagine that is costing us unnecessary funds to replace.”

“I hear what you're saying, but we aren't there yet,” said RJ as he continued to search for parts, some of which were barely stuck together with tape. “Besides, we aren't supposed to be copying music that way.”

“We are copying parts anyway when they go missing. We can even print out parts for musicians at the first rehearsal rather than giving them the originals. I did read that as long as we actually have the originals, we can copy them for the musicians. We just have to destroy the copies. Besides, there is nothing preventing the musicians from making copies themselves.”

“It seems like a lot of extra work,” replied RJ. I was hoping he realized the irony in his statement since digging and replacing music seemed a lot more time‐consuming. “I have another job, and that would be tough for me to do.”

“I don't mind making copies,” I said.

“Even so, it doesn't seem like the musicians will like it. They're used to having their parts mailed out, or if they're lucky, I give them their parts for the next concert at a performance.”

I thought about it for a moment. He was right in some ways. I thought it was a great idea, but I wasn't sure everyone in the symphony felt that way. It would help save money and time, but it was also important for the players to have input.

We finished finding the parts, and I took them to the scanner so I could email them out for those auditioning. It was a week out, which was kind of short notice, but at least we had the list of the audition music posted and emailed. Sending the parts was a benefit to the musicians, so they wouldn't have to search or even buy the parts for their audition.

As the light of the scanner moved back and forth, I thought of the perfect person to talk to in order to get insight into the symphony – Cindy Wittaker, the head of the orchestral committee. I decided to call her right away.

CALL TO CINDY

“Hey, Cindy,” I said when she answered the phone.

“Oh hey, Jerry, great to hear from you,” she answered. “How is your new position?”

“Great. It is actually the reason I called you. Do you have a minute?”

“Sure.”

“I spoke to RJ today about the issue of getting parts to musicians and then getting them back. Some of the musicians aren't getting their parts on time; they might get lost in the mail, or for all sorts of reasons. Losing parts and even mailing them is costing the symphony a lot of money. I've asked the board for raises, and they're on board, but I also promised I would find ways to cut costs and modernize some of our processes.”

“Sounds great. I agree. I hate getting my parts late, mostly because if I'm not prepared, Maestro knows it.”

“I agree. So my solution is to scan all the parts, email them to musicians, and then have copies available on the stands for the first rehearsal. That way, musicians don't have to have the originals, and they can have the parts on time.”

“What did RJ say?” asked Cindy.

“Well … he felt like it would be extra work and that the musicians wouldn't want it,” I replied.

“I, for one, would appreciate it, but I can understand his point. He has some musicians who might be tech adverse, mostly because they don't understand it.”

“Listen, I don't mind if we send out a couple of parts if a few people are against doing it by email,” I replied. “But it would really save time and resources to have the majority receive them by email, or we can even have them on a secured server for them to download.”

“Is that legal?” asked Cindy.

“I plan to talk to Sam about it more, to be sure,” I replied. “In the meantime, since you're the head of the orchestral committee, do you think you could survey the musicians and get their feel for it before we get into this any deeper?”

“I think that's an excellent idea. The committee works this week. We can send out emails and call people to get their take, and then I can give you the results the following week?”

“That would be perfect,” I replied.

After hanging up the phone, I realized it was time to go home, and my stomach turned a bit. Things weren't great, and I really wasn't looking forward to it. All I could do was to keep my chin up and hope for the best.

HOME IS WHERE THE HEART ISN'T

When I walked in the door, Laura was standing in the kitchen with her hands on her hips.

“You're late,” she said.

I looked at my watch. It was 5:30.

“Late for what?” I asked. “This is the usual time I get home.”

“Well, I have plans tonight, and I need to leave.”

“Plans? What plans?” I asked.

“I told you last week, my girlfriends and I were going on a girls' night out.”

I noticed she was dressed in an eye‐catching new dress, along with matching accessories. It was definitely not an outfit I had seen before.

“You mentioned something about it, but you never said it was for sure or when it was,” I replied.

“Well, I did tell you, and I have to leave in five minutes.” she pouted.

“Hey, Dad!” said Corey. “Am I still going to my lesson at six?”

Dang. It was Thursday. Laura usually took him on Thursdays, but I knew this was not the time to argue. Actually, I wasn't sure any time was a good time to argue. Laura had moved from passive‐aggressive to aggressive‐aggressive a lot lately, and so I was at a loss for what to do.

“Sure, buddy, load up your bass, and I'll be right there,” I said.

Once Corey left the room, I asked. “Where's Linda? And have they had anything to eat?”

“No, I didn't have time to make anything. And as for Linda, I think she's in her room. I need to get going. You don't have me blocked in, do you?” asked Laura.

“No, but can we have some time to talk this weekend?” I asked.

“About what?”

“Well, things have been a bit strained between us for a while and it seems to be getting worse. I think we need to talk about it,” I replied.

“Things are strained because you're never around. I have a life too, you know. I have to do everything for the kids while you do this new job thing.”

“Can we agree to talk about it later?” I answered.

“Sure, we can talk later,” Laura said as she grabbed her keys and purse and left for the evening.

I ran up the stairs to see Linda before I took off with Corey. I knocked on her door.

“Linda?” I asked. “Can I talk to you quickly?”

“Yeah,” said a small voice.

I was shocked to see Linda on her bed, hugging her pillow and crying.

“Oh, honey, what's the matter?” I asked.

Her eyes were wide, and she looked at me with an odd expression.

“You … you aren't mad?” she stuttered.

“Mad? About what?”

“Mom didn't tell you?”

I sat down at the foot of her bed. “Tell me what?”

“I got cut from the squad,” she said and began sobbing.

“You did what?” I handed her a box of tissues from her dresser.

“Well … I missed a couple of practices … but it was more about … my grades.”

“Your grades? I thought you were working on them?”

“I have been, but I couldn't get my GPA up before the end of midterms, and now I can't be on the team. Ms. Hassleback called Mom about it today. She was really mad and yelled at me. She blames you, and I told her it wasn't your fault. That you were helping me get my grades up, and that only made her madder. I thought you'd be mad too.”

“I know you've been working hard since we had that talk. Maybe I can call Ms. Hassleback tomorrow and see what can be done. I have to take Corey to his lesson. You want to come with us, and then we can get Chinese afterward?”

Linda jumped up and almost tackled me with her hug.

“I'd love that,” she said. “Thank you, Dad!”

* * *

As I drove to meet with Dr. Richardson, I thought a lot about my life. Things were going better in my new position, and I was learning a lot about project management, and for that I felt blessed. But my personal life was a mess. Maybe I needed to look at my home life as a project.

“Hey, Jerry,” said Dr. Richardson as he held out his hand. “A pleasure as always!”

I noticed a new stack of papers in front of him. The first couple of times I met with him, I felt overwhelmed and intimidated, but now I looked forward to our sessions and new things to learn.

I filled him in about my interactions with RJ and Cindy.

“That is absolutely brilliant,” Dr. Richardson replied. “I really think you're getting this project management thing.”

“Well, sometimes I still feel like I'm guessing,” I admitted.

“That's totally normal, and I would definitely say follow your gut. You have great instincts.”

“That's a relief,” I said with a sigh. “I really believe my ideas for the music distribution will be a benefit, but I also need RJ to be on board. If I get a positive report from the orchestra committee, I believe it will go a long way.”

“I couldn't agree with you more,” replied Dr. Richardson. “Please keep me updated.”

“I will,” I said. “So, what do you have for me today?”

“Today I want to go over strategic management.”

He briefly reviewed what we had discussed the previous week.

“If I'm going too fast, please let me know,” he said.

“I'm following you,” I replied. “I reviewed all those resource materials and articles you give me.”

Dr. Richardson handed me the stack of papers.

“For each of the strategic process groups, I've also created a mind map (see Figure 5.1), along with the information about each of the processes. Today I'm going to cover developing a portfolio strategic plan, developing the portfolio charter, defining the portfolio roadmap, and managing strategic change.”

My eyes got wide.

“I know it looks like a lot,” he continued. “But just bear with me. You'll want to focus and almost memorize each process and their inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs. A part of understanding the portfolio management processes is to understand those sixteen processes, but in order to understand each of those processes, we've talked about the inputs, the outputs, and the tools and techniques that go into each one.”

“My brain isn't as pliant as it was back in college,” I said. “Do you have any recommendations on how to memorize it?”

“I can tell you how I did it,” answered Dr. Richardson. “I used a memory technique where I had sixteen areas that I mapped out in my house and I assigned one of the portfolio processes to each area. And then as I walked through the house, into a room or into the garage, I would put up sticky notes in those areas to anchor the concepts of what I was learning. It helped me not only to memorize the sixteen processes in order, but also to memorize the various inputs, tools, and outputs for each of those sixteen processes.”

Figure 5.1 Strategic management mind map.

“Oh, I like that,” I said. “I'm writing that one down.”

He pointed at the next page. (See Figure 5.2.)

“Developing links between vision, mission, objectives, strategies, and action plans, which are programs and projects, is critical to strategic alignment. The strategic alignment question to consider when evaluating the linkage process is: Does the project build value for the organization? Is the investment aligned with the organization's enterprise architecture and core technologies? Does the project create organizational effectiveness? Is the organization capable of implementing the process successfully? Think about how this applies to your project of music distribution.”

Figure 5.2 Strategic linkage.

I thought about it. It wasn't just the buy‐in by the symphony. I needed to have a repeatable process for everyone to follow and it needed to be clear.

“Let's talk a little bit about business value,” Dr. Richardson continued. “Business value is defined as the entire value of the business. What's the business worth? It is the total sum of all tangible and intangible assets. Here are some questions to consider when you're thinking about understanding the role that you're going to have to play as a portfolio manager and helping to manage business value.”

He pointed to the next paper in the stack. (See Figure 5.3.)

“Each business that you're a part of will have a different definition based on its vision, mission, goals, objectives, where it's trying to go and what it's trying to do, and who it's trying to serve. And so you have to understand what value means to the symphony.”

I'd have to think about that a bit.

“Business drivers are items like reduce costs, improve profits, increase visibility, develop knowledge share. Those are business drivers. Things that are going to enhance the way the business runs. And there's a way in portfolio management that you're able to map projects and measure whether those projects are affecting those business drivers. So is your project concerning music distribution a business driver?”

“I believe it is,” I answered.

“I agree,” replied Dr. Richardson. “The whole purpose of enterprise architecture and portfolio management working together is that enterprise architecture looks at what types of things we have in place right now. Think of it this way: with enterprise architecture and portfolio management, when it comes to this capability concept, it's like if I want to go from Pensacola, Florida, to Tampa, Florida – that's a long way, right? And so it depends on the capability I have. If I only have a bicycle, then that is not really going to work. If I have a car, then yes. Now, it's going to take probably seven or eight hours to get there. But if I could fly on a plane, if I had the capability to access an aircraft, I could be there within an hour.”

Figure 5.3 Understanding business value.

“I've been thinking of ways to scan the music and how to distribute them through a database program so I can send the correct parts to the correct people. I believe that RJ will have to help me with that.”

“So you need to have that in place before you can fully switch over to electronic copies of the music.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “I really appreciate your help because I felt like my idea would be easy to do since most people have email.”

“Exactly. That is why we're discussing strategy,” replied Dr. Richardson. “When you really think about the concept of business value and developing the capabilities to deliver the value, you have to think about it from a mechanical standpoint of what vehicle, what systems, what processes, what tools do we have that can get us there? So think of the bicycle as a tool or a process. Is that process capable of getting me to my destination in a timely manner? If it's not, then I need to upgrade that process. Whether it's upgraded from a bicycle to a car, or if I have to get there within an hour on a regular basis, then I'm going to be upgrading from a car to buying a plane ticket.”

“I get it,” I agreed and made some quick notes for myself.

“Next, consider what criteria you will use to prioritize your investment strategy. And criteria are along the lines of the business values on drivers, but it's taking the drivers to a different level.” (See Figure 5.4.)

“Consider how much your drivers are reducing costs. Consider your music distribution. How much is it actually going to save the symphony not to have to mail and replace parts?”

I made a note to get those numbers together.

Figure 5.4 Selecting and prioritizing business drivers.

“Objectives must be specific in scope, action‐oriented, and able to serve as high‐level goals for an individual project,” Dr. Richardson continued. “It should have been agreed upon through a consensus approach by as wide a group of senior managers and stakeholders as realistically possible. That's why going to your orchestra committee to survey the symphony is a great idea. You may want to talk to your board as well to get their take on it. You see, portfolio management takes a holistic view of an organization's strategy – both the business and executive leadership that project proposals by matching them with the company's strategic objectives.”

I thought about some of my other ideas, such as arranging to get people paid by automatic deposit, and realized that similar surveying of the symphony might be a good idea.

“One of the key goals of this part of the portfolio management process is alignment among key leaders. Let's say you have the CIO, a CFO, a chief marketing officer, and a chief human resource officer. When you list out these business drivers – let's say increase revenue, manage risks, enhance security, reduce costs, drive efficiency, enhance collaboration, and increase knowledge – well, you can bet that the CFO is going to be interested in increasing revenue and reducing costs. The CIO is going to be interested in enhancing security, possibly enhancing collaboration, increasing knowledge share. The human resource manager, well, they're going to be really interested in enhancing collaboration and increasing knowledge. What tends to happen is those leaders tend not to be on the same page as far as the priority of each of those drivers.”

“You've worked with other companies. How do you get them on the same page?” I asked.

“I use a tool called the analytical hierarchy process,” he said, as he shuffled through the stack and showed me a diagram. (See Figure 5.5.)

“It allows the various leaders to vote on the value and the priority of those drivers,” he explained. “The algorithm on the backend basically calculates and then develops a unified view based on everyone's input and then prioritizes the business drivers. It allows you to prioritize those drivers. And then the leaders can talk about it. One of the great benefits of portfolio management to the business is that it gets the leadership team on the same page when it comes to prioritization of the business activity, the business drivers, and the direction of the organization. Now I understand that this may not work with your symphony, but it's worth looking at and understanding. You're already doing these things on a smaller scale directly with the board and other departments.”

Figure 5.5 Analytic hierarchy process (AHP).

So I was doing some things right. That was great to hear. Because of Laura's opposition to my job and my ability to do it, there were times I really doubted myself.

“Once you've gone through and prioritized your business drivers using the tools of the analytical hierarchy process, you want to identify the existing or new items that you want to put into your portfolio,” Dr. Richardson continued. “I refer to these as components. A component can be a project. A component could be a portfolio or a sub‐portfolio. A component could be a program. Or it could even be operational work that makes up the portfolio that you're putting together. Your music distribution plan is a component.”

“I get it,” I replied.

“You want to evaluate the current portfolio. You want to weed out the portfolio of projects not aligned with the corporate strategy. You also want to identify new proposed projects in the portfolio. You've already begun doing this, but you'll continue this weeding over time. And then, once you have those projects, you'll want to optimize and recalibrate to achieve an optimal value. Additionally, you want to ask these questions: How many projects can the organization absorb at one time? Does the organization have the capacity to deliver the selected portfolio? And does the portfolio need to be synchronized to adjust demand and provide buffering? You ran into this issue when you first made your proposal to the board.”

“Even though that was only a few weeks ago, it feels like a lifetime ago,” I said. “I've learned so much about portfolio management; I wish I could have a redo.”

“I'm sure they knew you had to learn more about your position, and they seemed patient with you. Can you imagine how prepared you'll be with next year's budget?”

He was right. I had to cut myself a little slack. I needed to keep learning and improving. I just hoped Fernando, Sam, and the board could see the improvements.

“Now you have prioritized your business drivers, and you created a consensus among your leadership team,” continued Dr. Richardson. “You've identified projects, existing projects, the new projects, and operational work that aligns to the organizational strategy because you've had these new business drivers that have been prioritized. The next thing you want to do is to categorize your project investment. How do you do that? I like to leverage the Gartner Framework for transforming, growing, and running the business.”

I was taking furious notes. It seemed like a lot of pieces and parts for the symphony, but I wanted to learn portfolio management on a bigger scale in case I wanted to move into another position with a larger organization in the future.

“According to the Gartner Framework, when you transform the business, any projects that fit within the transform‐the‐business bucket, they are investments in new markets, ventures, mergers and acquisitions, new products, or outsourcing efforts.” Dr. Richardson explained. “A transform business project is a project that is going to create disruption in the market or disruption in the company. A grow‐the‐business project is one you invest in to expand the company's scope of products and services, upgrade software, add incremental capabilities, and develop new skills. And then, the run‐the‐business projects are investments to keep the business operational, like maintenance contracts and disaster recovery contracts. So now we have a project portfolio of a collection of components that we've actually put into categories for investments and for investing in.”

“Tell me more about the software and systems that you use to prioritize these projects,” I encouraged him. (See Figure 5.6.)

Figure 5.6 Project prioritization.

“There are tools like Microsoft Project Server, Portfolio Management Tool, and TransparentChoice. And there are other third‐party tools that you can use as well. But the idea is that once each project has been evaluated against the objectives, the business drivers, KPIs, and business benefit statements, it can be assigned to a strategic value. And the system does that. And so, based on the system that you're using, the bubbles placement and the size and color will depend on the criteria you use when you're prioritizing your projects. And obviously, in this scenario, everything that's in the upper right‐hand corner in the darker area has greater value to the business than the ones in the lower, lighter‐shaded area.”

He then placed some other graphs in front of me. (See Figure 5.7.)

“This portfolio analysis tool is the Microsoft Project Server portfolio analysis tool that's inside of Project Server. It can help you to identify the strategic alignment of projects and to prioritize the projects. You can create scenarios, probabilities, and cost‐benefit analyses of the entire portfolio, not just a single project. You can look at resource capacity, and interdependencies between projects.”

Figure 5.7 Portfolio analysis.

It looked intimidating, but I was developing goals. Perhaps some of this software could be used as I developed more projects.

“With the portfolio analysis, you're rationalizing the portfolio. It's necessary to ensure that it does not contain multiple projects that are superfluous or mutually exclusive. Each category of benefits should be consolidated to evaluate whether the target KPIs can be achieved. Portfolio optimization considers the organization's constraints, money, resources, time, and level of risk. The cost‐benefit analysis seeks to define the benefit that will be provided by the portfolio and compares it to the cost of the portfolio programs and projects.”

“This cost‐benefit analysis sheet is per project. It is not only important to look at just the investments and the cost‐benefit analysis of the single project. It is important to consider the cost‐benefit analysis of the entire portfolio as well.”

“The portfolio roadmap is the investment roadmap, which provides a short‐, medium‐, and long‐term view of the portfolio investment strategy. The roadmap facilitates dialogue and builds an agreement on the organization's funding and resource allocation plan, as well as its alignment to goals and objectives.”

This would be extremely important as I built and worked on next year's budget.

“Are you getting all this?” Dr. Richardson asked.

“Most of it,” I admitted.

“There is a lot to absorb, I know. Here are some more Harvard Business Review articles that might help you.” I took a stack of articles neatly stapled and put them in a separate pile.

“Here is a checklist that I think will help you understand the process a bit better,” he said. (See Figure 5.8.)

“This is a process that can be used for each project,” he said. “To be managed as a project, you need to start off with a charter for the portfolio management practice. You need to have an executive sponsor, whether it's the CIO or a partner, or someone at the C level who can help shepherd this through because it will require a major culture change in your organization. In your case, it would be the board and your director, Sam. You also have to develop a project plan or implementation plan and then clarify roles and responsibilities. You are doing that with RJ and Cindy. I would recommend using a RACI chart.”

“What is that?” I asked.

As a project:

|

Figure 5.8 Steps to implement a PPM practice.

“It's a chart that covers the areas of responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed around the processes of things that you have to deal with.”

“Makes sense,” I said.

“Then you have to evaluate the current portfolio and conduct a portfolio gap analysis to see where you are. One of the things that I use is a maturity model assessment to do this. It really helps to identify what the gaps are in an organization and then helps them to get aligned to that.”

“Next, you will want to weed out products that are not aligned to the strategy, which we just talked about. This is followed by developing your portfolio management processes and selecting and implementing a tool. You can use a spreadsheet for the symphony. I believe you have already started one.”

“I have,” I replied.

“If you were working for a much larger organization, I would recommend using an enterprise system that's been created and built for that. Then you would roll out some sort of training that speaks to the executive team to coach them through the process and help them understand their role as executives and executive sponsors of projects and portfolios, followed by coaching the portfolio managers, the PMO, and being very clear about which PMO you're talking about. In the case of your music distribution, it will be clear that you need to teach RJ.”

I hoped that RJ was going to be on board and not resistant to the new process should it get that far.

“Then you want to conduct a pilot of your portfolio process. In this case, you'll pick a concert and try out the new process. You'll continue mailing music and try the new approach with a sample of the orchestra. You don't want to quit the old system and implement the new one all at once without testing it. I recommend trying the pilot for a few concerts to work out the bugs before replacing the old system entirely. By running a pilot, you create a center of excellence of people who understand the new process, all the terminology, the ways you're going to leverage the systems, and the tools you're going to introduce.

“You will also need some coaching and mentoring and you'll have to conduct an audit of your environment over time. Because once you build out the portfolio, you're constantly having to go back through it and report on what you're doing. You constantly have to recalibrate the portfolio, especially if there's a market shift, if there are new directions or new changes to the strategy because of a storm or any kind of act of God or things that happen. Or there could be a major disruption in the business or in the market that you have to reply to very quickly. You need to be able to do that.”

“I understand,” I said. “I really appreciate this.”

“Do you have any questions?” Dr. Richardson asked.

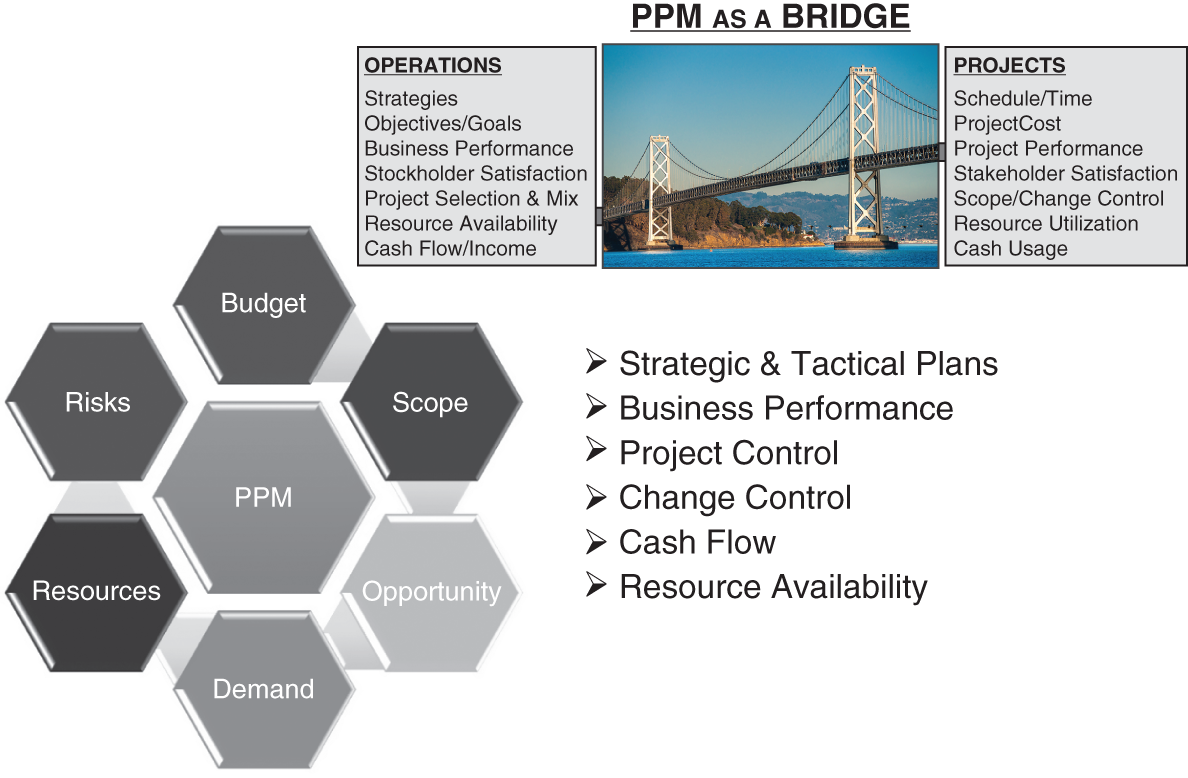

“As I've been reading the articles and hearing you today, I wonder: Does the project portfolio management process work as a bridge, or is it a hub?” (See Figure 5.9.)

“Great question,” he replied. “It's one I get often.”

Figure 5.9 Is PPM a bridge or a hub?

Credit: Luciano Mortula-LGM/Adobe Stock

“A bridge basically connects operations and strategy to projects,” explained Dr. Richardson. “But the hub‐and‐spoke concept is that you have portfolio management in the middle, and it touches all of these areas, like risk and budget and scope, resources, and demand. Harvey Levine, who wrote an important book on project portfolio management, takes the position that portfolio management is not a bridge, but it's a hub that acts as a decision support environment that provides access to all the information across an organization, the ability to provide analytical insights, a vehicle for communication, alignment of investments to organizational objectives, and a platform for controlling risk.”

“I see,” I replied.

“Whenever you're thinking about the role that you're going to play when you take the position of portfolio manager in an organization, you become the center part of a wheel where you're touching budget, risk, scope, and alignment of products and programs. You really help to move things along. Again, if you use that analogy of the corpus callosum I mentioned to you last week, you're taking the vision of the organization and helping the part of the body that can execute it or create actions around it to get those things done. That becomes a really critical part of any business to have a well‐oiled portfolio management process and for you to be a top‐notch, elite portfolio management practitioner.”

“Well, that's my goal,” I said. “To be a top‐notch practitioner.”

“I have to say, within record time you have grasped concepts that most of my grad students struggle with.”

“I really appreciate that. I have my work cut out for me,” I said. “Same time next week?”

“You bet.”

As I got into my car, I thought about everything that had been going on this week. I came to the conclusion that I really needed to get my personal life sorted out to have any chance of keeping my new position under control. Projects were going to begin to overlap, and I needed to be on my A‐game. I couldn't do that if my marriage and family were falling apart.

Dr. Richardson's Tips

- Developing links between vision, mission, objectives, strategies, and action plans, which are programs and projects, is critical to strategic alignment. The strategic alignment question to consider when evaluating the linkage process is: Does the project build value for the organization? Is the investment aligned with the organization's enterprise architecture and core technologies? Does the project create organizational effectiveness? Is the organization capable of implementing the process successfully?

- Objectives must be specific in scope, action‐oriented, and able to serve as high‐level goals for an individual project. It should have been agreed upon through a consensus approach by as wide a group of senior managers and stakeholders as realistically possible.

- You can evaluate the current portfolio and conduct a portfolio gap analysis to see where you are. One of the things that I use is a maturity model assessment to do this. It really helps to identify what the gaps are in an organization and then helps them to get aligned to that.