4 |

The Influence of the Popular Arts |

||

Film as a narrative form had numerous influences, particularly the popular novel of the nineteenth-century1 and the theatrical genres of spectacle, pantomime, and melodrama.2 The character and narrative conventions of those forms were adapted for film through editing. The types of shots required and how they were put together are the subject of Chapter 1. This chapter is concerned with the ongoing development in the popular arts and how they affected editing choices. In some cases (radio, musicals), they expanded those choices, and in others (vaudeville, theatre), they constrained those choices.

The interaction of these popular forms with film broadened the repertoire for film and eventually influenced other arts. However, film's influence on theatre, for example, took much longer. That influence was not apparent in theatrical production until the 1960s. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was the influence of theatre and radio that shaped film and film editing.

VAUDEVILLE

VAUDEVILLE

In the work of Griffith and Vidor, narrative goals affected editing choices. In the subsequent work of Eisenstein and Pudovkin, political goals influenced editing choices. Vaudeville, as in the case of the documentary, presented yet another set of priorities, which in turn suggested different goals for editing.

Vaudeville, whether associated with burlesque or, later, with the more respectable theatre, offered a different audience experience than the melodramas and epics of Griffith or the polemics of the Russian revolutionary filmmakers. Vaudeville embraced farce as well as character-based humor and physical humor as well as verbal humor. As Robert C. Allen suggests, diversity was a popular characteristic of vaudeville programs: “A typical vaudeville bill in 1895 might include a trained animal act, a slapstick comedy routine, a recitation of ‘inspirational’ poetry, an Irish tenor, magic lantern slides of the wilds of Africa, a team of European acrobats, and a twenty-minute dramatic ‘playlet’ performed by a broadway star and his/her company.”3

Vaudeville skits didn't have to be realistic; fantasy could be as important as an everyday situation. Character was often at the heart of the vaudeville act. Pace, character, humor, and entertainment were all goals of the act. In the early period, the audience for vaudeville, just like the early audience for film, was composed of the working class and often immigrants.4 Pantomime and visual action were thus critical to the success of the production because routines had to transcend the language barrier.

We see the influence of vaudeville directly in the star system. Both Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton began in vaudeville. In their film work, we see many of the characteristics of vaudeville: the victim, the routine, the performance, and a wide range of small set-pieces (brief dramatized comic scenes) that are either stand-alone routines or parts of a larger story. What unifies the Chaplin and Keaton films is their characters and the people they represent: in both cases, ordinary men caught up in extraordinary situations.

In terms of editing, the implications are specific. First, the routine is important and must be clearly articulated so that it works. Second, the persona of the star—Chaplin or Keaton—must remain central; there can be no distractions from that character.

The easiest way to illustrate these principles is to look at Charlie Chaplin's films. Structurally, each film is a series of routines, each carefully staged through Chaplin's pantomime performance. Chaplin called City Lights (1931) “a comedy romance in pantomime.” The opening sequence, the unveiling of a city statue on which Chaplin's character, “the little tramp,” is sleeping, is both absurd and yet logical. Why is a man sleeping in the arms of a statue? Yet this very absurdity emphasizes the homelessness of the character. He is in every sense a public ward. This type of absurdity is notable in many of Chaplin's sequences, for example, the eating of shoelaces as spaghetti in The Gold Rush (1925) and the attempted suicide in City Lights. Absurdity is often at the heart of a sequence when Chaplin is making a point about the human condition. Perhaps the most absurd is the scene in The Great Dictator (1940) in which the dictator plays with a globe as if it were a beach ball. Absurdity and logic are the key elements to these vaudeville-like routines in Chaplin's films.

Perhaps no film by Chaplin is as elaborate in those routines as Modern Times (1936). The structure is a series of routines about factory life and personal life during the Depression. The first routine focuses on the assembly line. Here, the little tramp is victimized first by the pace and regimentation of the line and then by a lunch machine. He suffers an emotional breakdown, is hospitalized and released, and when he picks up a red flag that has fallen off a passing truck, he is arrested as a Communist. In jail, he foils a jail break, becomes a hero, and is released back into society. He meets a young woman, fantasizes about domestic life with her, and sets about getting a job to achieve that life. His attempt as a night watchman fails. When the factories reopen, he takes a job as a mechanic's assistant. A strike ends the job, but after another spell in jail, he gets a job as a singing waiter. He succeeds, but the young woman must flee for breaking the law. In the end, the tramp is on the road again, but with the young woman. Their life is indefinite, but he tries to smile.

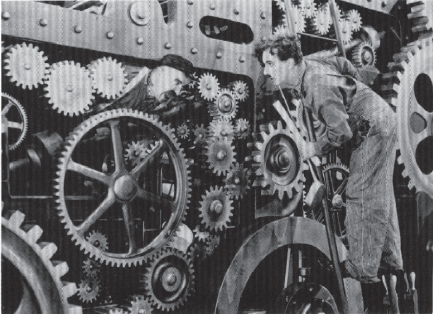

Every scene in the film is constructed as a vaudeville routine. It has an internal logic and integrity. Each is visual and often absurd, and at its core is Chaplin portraying the little tramp. The scene in which Chaplin works as a mechanic's assistant presents an excellent example. Chaplin tries to be helpful to the mechanic (portrayed by Chester Conklin), but at each step, he hinders his boss. First, the oil can is crushed in the press, and eventually all of the mechanic's tools are crushed. Even the mechanic is swallowed up by the machinery (Figure 4.1). Now the absurdity twists away from the mechanic's fate; the lunch whistle blows, so the tramp attempts to feed the mechanic, who at this stage is upside down. To help him drink the coffee, he uses an oil spigot. He discards it for a whole chicken whose shape works as a funnel. As absurd as the situation seems, by using a chicken, the mechanic can be fed coffee. Finally, lunch is over and the mechanic can be freed from the machine. Once freed, however, the job ends due to a strike.

In terms of editing, the key is enough screen time to allow the performance to convince us of the credibility of the situation. The emphasis throughout the scene is on the character's reaction to the situation, allowing us to follow through the logic of the scene. In every case, editing is subordinate to setting and performance. Pace is not used for dramatic purposes. Here, too, performance is the key to the pacing.

Figure 4.1 |

Modern Times, 1936. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

If one looks at the work of Keaton, Langdon, or Harold Lloyd in the silent period or the Marx Brothers, Abbott and Costello, or other performer-comedians in the sound period, the same editing pattern is apparent. Editing is determined by the persona of the character, and affirmation of that persona is more important than the usual dramatic considerations for editing. In a sense, vaudeville continued in character in the films that starred former vaudeville performers. Beyond the most basic considerations of continuity, the editing in these films could take any pattern as long as it supported the persona of the actor. Within that range, realism and surrealism might mix, and absurdity was as commonplace as realism. This style of film transcends national boundaries, as we see in the films of Jacques Tati and Pierre Etaix of France and the Monty Python films of England.

THE MUSICAL

THE MUSICAL

The musical's importance is underlined by the success of The Jazz Singer (1927), the first sound picture. As mentioned earlier, however, the early sound films that favored dialogue-intensive plots tended to be little more than filmed plays.

By the early 1930s, however, many directors experimented with camera movement to allow for a more dynamic approach, and post-synchronization (adding sound after production is completed) freed the musical from the constraints of the stage. As early as 1929, King Vidor post-synchronized an entire musical, Hallelujah (1929). However, it was the creative choreography of Busby Berkeley in Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) that pointed the direction toward the dynamic editing of the musical. Berkeley later became one of the great directors of the musical film.

The musical posed certain challenges for the editor. The first was the integration of a dramatic story with performance numbers. This was most easily solved by using dramatic stories about would-be performers, thus making the on-stage performance appear to be more natural. The second challenge was the vaudeville factor: the need for a variety of routines in the film, comedy routines as well as musical routines. This was the greater challenge because vaudeville routines could not be integrated as easily into the dramatic story as could a few musical numbers. Another dimension from vaudeville was the persona of the character. Such actors as Fred Astaire and Edward Everett Horton had to play particular characters. The role of the editor was to match the assembly of images to the star's persona rather than to the drama itself. Despite these limitations, the musical of the 1930s and beyond became one of the most dynamic and visual of the genres.

A brief examination of Swing Time (1936) illustrates the dynamism of the musical. The director, George Stevens, tells the dramatic story of performer-gambler Lucky Garnett (Fred Astaire) and his relationship to performer Penny Carroll (Ginger Rogers). The dramatic story reflects the various stages and challenges of the relationship. This dimension of the film is realistic and affecting, and the editing is reminiscent of Broken Blossoms or The Big Parade.

The editing of the musical numbers, on the other hand, follows the rhythm of Jerome Kern's music and highlights the personae of Astaire and Rogers. The scale of these numbers is closer to the Ziegfeld Follies than to vaudeville, and consequently, the editing of these numbers could have differed markedly from the editing of the balance of the film. However, because Stevens tended to be a more “realistic” director than Berkeley, these numbers are edited in a manner similar to that of the dramatic portion of the film. There is thus little dissonance between the performance and dramatic sections of the film.

All of the musical numbers—the dancing lesson, the winter interlude, the nightclub sequence, “Bojangles”—have a gentle quality very much in key with Kern's music. Other directors, notably Vincente Minnelli, George Sydney, Stanley Donen, and Gene Kelly, were more physical and assertive in their editing, but this style complemented the persona of frequent star Gene Kelly. Later, directors Robert Wise in West Side Story (1961) and Bob Fosse in Cabaret (1972) were even freer in their editing, but their editing decisions never challenged the rhythm of the music in their films. The scores were simply more varied, and where the music was intense, the director could choose a more intensified editing style, thus using editing to help underscore the emotions in the music.

The musical was a much freer form to edit than films such as Modern Times. The narrative, the persona of the performer-star, and the character of the music influenced the editing style. Together with the strengths of the director of the film, the editing could be “stage-bound” or free.

THE THEATRE

THE THEATRE

Like the musical, the theatre became an important influence on film with the coming of sound. Many plays, such as Oscar Wilde's The Marriage Circle (1924), had been produced as silent films, but the prominence of dialogue in the sound movies and the status associated with the stage provided the impetus for the studios to invite playwrights to become screenwriters. Samuel Raphaelson, who wrote The Jazz Singer, and Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, who wrote The Front Page (1931), are among those who accepted. Eugene O'Neill, Maxwell Anderson, and Billy Wilder were also invited to write for the screen.

There was, in the 1930s, a group of playwrights whose work exhibited a new political and social realism. Their form of populist art was well suited to the most populist of mediums: film. The works of Robert Sherwood, Sidney Kingsley, Clifford Odets, and Lillian Hellman were rapidly adapted to film, and in each case, the playwrights were invited to write the screenplays.

How did these adaptations influence the way the films were edited? Two examples suggest the influence of the theatre and how the transition to film could be made. Kingsley's Dead End (1937) and Hellman's The Little Foxes (1941) were both directed by William Wyler.

Dead End is the story of adolescents who live in a poor neighborhood in New York. They can go the route of trouble and end up in jail, or they can try to overcome their environment. This naturalistic movie features an ensemble of characters: a gang of youths (as the Dead End Kids, the group went on to make a series of films), an adult who is going “bad,” and an adult who is trying to do the right thing. No single character dominates the action. Characters talk about their circumstances and their options. There is some action, but it is very little by the standards of the melodrama or gangster genres. Consequently, the dialogue is very important in characterization and plot advancement.

The editing of this film is secondary to the staging. Cutting to highlight particular relationships and to emphasize significant actions is the extent of the editing for dramatic purposes. Editing is minimalist rather than dynamic. Dead End is a filmed play.5

In The Little Foxes, Wyler moved away from the filmed play. He was greatly aided by a play that is character-driven rather than polemical. The portrayal of the antagonist, Regina (Bette Davis), establishes the relationships within a family as the heart of the play. Behavior can be translated into action as a counterweight to the primacy of dialogue, as in Dead End. Because relationships are central to the story, Wyler continually juxtaposed characters in foreground–background, side frame–center frame variations. The editing thus highlights the characters’ power relationships or foreshadows changes in those relationships. The editing is not dynamic as in a Pudovkin or an Eisenstein film, but there is a tension that arises from these juxtapositions that is at times as powerful as the tension created by dynamic editing.

Wyler allowed the protagonist–antagonist struggle to develop without relying solely on dialogue, and he used staging of the images to create tension. This method foreshadowed the editing and framing relationships in such Cinemascope films as East of Eden (1955).

Although its style of editing is not as dynamic as in such films as M nor is it as restricted as in such films as Dead End, The Little Foxes illustrates a play that has been successfully recreated as a film. Because of the staging and importance of language over action, character over event, in relative terms the film remains more strongly influenced by the conventions of the theatre and less by the evolving conventions of film than were other narrative sources with more dynamic visual treatment. Westerns and traditional gangster films are very visual rather than verbal.

RADIO

RADIO

Whether film or radio was a more popular medium in the 1930s is related to the question of whether film or television is a more popular medium today. There is little question today that the influence of television is broader and, because of its journalistic role, more powerful than film. The situation was similar with radio in the 1930s.

Radio was the instrument of communication for American presidents (for example, Franklin D. Roosevelt's “fireside chats”) and for entertainers such as Jack Benny and Orson Welles. In a sense, radio shared with the theatre a reliance on language. Both heightened (or literary) language and naturalistic language were readily found in radio drama. Beyond language, though, radio relied on sound effects and music to create a context for the characters who spoke that dialogue.

Because of its power and pervasiveness, radio was bound to influence film and its newly acquired use of sound. Perhaps no one better personifies that influence than Orson Welles, who came to film from a career in theatre and in radio. Welles is famous for two creative achievements: one in film (Citizen Kane, 1941), the other in radio (his 1937 broadcast of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds).

As Robert Carringer suggests,

Welles’ background in radio was one of the major influences on Citizen Kane. Some of the influence is of a very obvious nature—the repertory approach, for instance, in which roles are created for specific performers with their wonderfully expressive voices in mind. It can also be seen in the exaggerated sound effects. The radio shows alternated between prestigious literary classics and popular melodrama.

Other examples of the radio influence are more subtle. Overlapping dialogue was a regular feature of the Mercury radio shows, as were other narrative devices used in the film—the use of sounds as aural punctuation, for instance, as when the closing of a door cues the end of a scene, or scene transitions in mid-sentence (a device known in radio as a cross fade), as when Leland, talking to a crowd in the street, begins a thought, and Kane, addressing a rally in Madison Square Garden, completes it.6

Indeed, from the perspective of narrative structure, Citizen Kane is infused by the influence of radio. The story is told via a narrator, a dramatic shaping device central to radio drama. Welles used five narrators in Citizen Kane.7

Although the story proceeds as a flashback from Kane's death, it is the various narrators who take us through key events in Kane's life. To put the views of those narrators into context, however, Welles used a newsreel device to take us quickly through Kane's life. With this short newsreel (less than 15 minutes), the film implies that Kane was a real and important man whose personal tragedies superseded his public achievements. The newsreel leaves us with an implicit question, which the first narrator, the newsreel reporter, poses: What was Kane's life all about? The film then shifts from newsreel biography to dramatic mystery. This is achieved through a series of radio drama devices.

In Movietone fashion, a narrator dramatizes a visual montage of Kane's life; language rather than image shapes the ideas about his life. The tone of the narration alternates between hyperbole and fact. “Xanadu, where Kublai Khan decreed his pleasure dome” suggests the quality of Kane's estate, and the reference to “the biggest private zoo since Noah” suggests its physical scale. The language is constantly shifting between two views of Kane: the private man and the public man. In the course of the newsreel, he is called “the emperor of newsprint,” a Communist and a Fascist, an imperialist and a pacifist, a failed husband and a failed politician. Throughout, the character of language drives the narrative.

The music throughout the newsreel shifts the focus and fills in what is not being said. Here, too, Welles and composer Bernard Herrmann used music as it was used in radio.

The other narrators in the film—Thatcher, Leland, Bernstein, and Susan (Kane's second wife)—are less forthcoming than the newsreel narrator. Their reluctance helps to stimulate our curiosity by creating the feeling that they know more than they are telling. The tone and language of the other narrators are cautious, circumspect, and suspicious—far from the hyperbole of the newsreel. The implication is dramatically very useful because we expect to learn quite a lot if only they will tell us.

Beyond the dramatic effect of the narration device, the use of five narrators allowed Welles and screenwriter Herman I. Mankiewicz to tell in 2 hours the story of a man whose life spanned 75 years. This is the principle benefit of using the narrators: the collapse of real time into a comprehensive and believable screen time.

This challenge of collapsing time was taken up by Welles in a variety of fascinating ways. Here, too, radio devices are the key. In the famous Kane–Thatcher scene, the completion of one sentence by the same character bridges 17 years. In one shot, Kane is a boy and Thatcher wishes him a curt “Merry Christmas,” and in the next shot, seventeen years later, Thatcher is dictating a letter and the dialogue is “and a Happy New Year.” Although the device is audacious, the audience accepts the simulation of continuity because the complete statement is a well-known one and both parts fit together. Because Thatcher looks older in the second shot and refers to Kane's 25th birthday, we accept that 17 years have elapsed.

The same principle applies to the series of breakfast table shots that characterize Kane's first marriage. The setting—the breakfast table—and the time—morning—provide a visual continuity while the behavior of Kane and his wife moves from love in the first shot to hostility and silence in the last. In 5 minutes of screen time, Kane and editor Robert Wise collapse eight years of marriage. These brief scenes are a genuine montage of the marriage, providing insights over time—verbal punctuations that, as they change in tone and language, signal the rise and fall of the marriage. Here, too, the imaginative use of sound over image illustrates the influence of radio. See Figure 4.2.

Welles used the sound cut to amuse as well as to inform. As David Bordwell describes it, “When Kane, Leland and Bernstein peer in the Chronicle window, the camera moves up the picture of the Chronicle staff until it fills the screen; Kane's voice says ‘Six years ago I looked at a picture of the world's greatest newspaper staff-.-.-.’ and he strides out in front of the same men, posed for an identical picture, a flashbulb explodes, and we are at the Inquirer party.”8 Six years pass as Kane celebrates his human acquisitions (he has hired all the best reporters away from his competition) with sufficient wit to distract us from the artificiality of the device.

Finally, like Fritz Lang in M, Welles used sound images and sound cuts to move us to a different location. Already mentioned is the shift from Leland in the street to Kane at Madison Square Garden, in which Kane finishes the sentence that Leland had started. The sound level shifts from intimate (Leland) to remote (Kane), as the impassioned Kane tries harder to reach out and move his audience. The quality of the sound highlights the differences between the two locations, just as the literal continuity of the words spoken provides the sense of continuity.

Figure 4.2 |

Citizen Kane, 1941. ©1941 RKO Pictures, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Another example of location shift together with time shift is the opera scene. Initially Kane's second wife, Susan Alexander, is seen being instructed in singing opera. She is not very good. Her teacher all but throws up his hands. Kane orders him to continue. Susan tries to reach higher notes, even higher in pitch than she has managed so far. In the next shot the orchestration of the music is more elaborate. Susan is reaching for an even higher note. And visually she is on stage surrounded by her fellow actors and singers. The opera is approaching its climax—the death scene.

Again, Welles has used sound to provide both continuity—Susan singing in training to Susan singing in the performance of the opera—and drama—the stakes are far higher in performance than in training. As we anticipate, both Susan and Kane are humiliated by the performance. Just as Kane did not accept the advice of the teacher, he vows not to accept the views of the audience and his main critic, Jed Leland. Only Susan is left trapped in humiliation.

In the opera scene, time and place change quickly, in a single cut, but the dramatic continuity of growing humiliation and loss demark another step in the emotional descent of Citizen Kane.

These radio devices introduced by Welles in a rather dramatic fashion in Citizen Kane became part of the editor's repertoire, but they awaited the work of Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese, more than 30 years later, to highlight for a new generation of filmmakers the scope of sound editing possibilities and the range that these radio devices provide.