Conceptual Foundation for the Case Study Approach

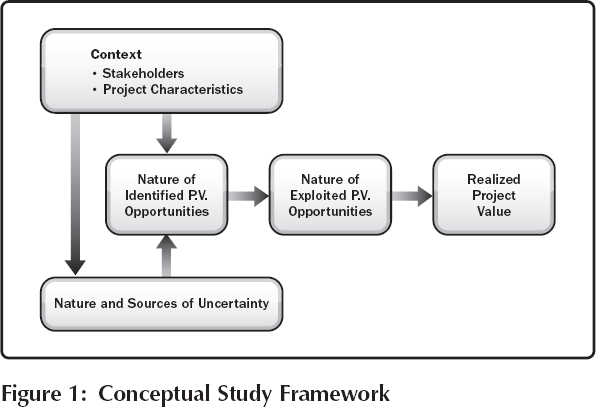

The conceptual framework (see Fig. 1) for this study reflects the basic theoretical arguments of the economists and the entrepreneurship research field. It represents the main concepts and the relationships between them. The main focus of this study is to explore the nature of exploited project value opportunities (P.V. opportunities). Therefore, the framework differentiates between opportunities that might have been identified and those that were exploited during the implementation of a project. We also try to understand the existence of project uncertainty and specific situations that are related to that uncertainty. Another important aspect of the study is to explore the relationship between situations of uncertainty and the nature of the identified opportunity. Who identified the P.V. opportunities, and which ones were exploited are core questions in the research. Specific characteristics of the project, as well as the involvement of stakeholders, are interesting with regard to both uncertainty and opportunity.

The conceptual framework was necessary to derive and organize questions for the interviews. The components of the framework are discussed in the following sections.

Differentiating Project Success from Project Value

In general, the definition and measurement of project success is controversially discussed in many different contexts. The problem is the lack of a theoretical foundation for measuring project performance. Most authors agree that project success is insufficiently defined by the TC-paradigm, yet a general definition is still not agreed upon. The problems of defining and measuring project success are related at the conceptual level, as many authors start with the TC-paradigm in mind and try to extend and supplement it. This approach does not change the basic principles under which the criteria are selected. Project success is still measured as an adherence to the triple constraint objectives, with the addition of some other criteria that should be fulfilled to address “local” needs. It is measuring project success toward a baseline that is predetermined and defined before the project is started and modified during the project execution. From a project manager's perspective, the challenge is avoiding variation from the baseline or from any other predetermined success criteria. As an example, quality is usually referred to and measured by the degree of conformance to a predetermined standard of quality performance.

One problem, as Freeman and Beale (1992) pointed out, is that, “Success means different things to different people.” This perspective is supported by the view that whether a project succeeded or failed could be an ambiguous determination (Belassi & Tukel, 1996; Pinto & Slevin, 1989; Freeman & Beale, 1992). Other authors differentiate between project success and project management success (Baccarini, 1999; de Wit, 1988), or they add criteria that are industry specific, as with Pocock, Hyun, Liu, and Kim (1996), who suggest that construction projects include the absence of legal claims as an indicator of project success. In their example, both contractors and clients may be subject to legal claims, as well as financial loss and contract delay in the construction project. (See also Kometa, Olomolaiye, and Harris, 1995; Songer and Molenaar, 1997; and Kumaraswamy and Thorpe, 1996.)

This approach does not necessarily lead to the value maximization of a project, and dissuades one from seeking or considering potential alternatives. A valid performance measure with this approach would only be possible if the project is implemented under completely determined conditions. Negative deviation would then be directly related to the poor management performance of the project manager or stakeholders. This also means that projects are successful if the baseline is met.

The central problem is that uncertainties are not taken into account. Contextual conditions of projects are constantly changing, and what once looked like criteria to define value could shift dramatically. A new product development project that is suddenly facing a competing product from another firm is one example of that kind of change. Under this new contextual condition, time or additional product features might be the most important performance criteria. The other problem is that the baseline has to be “realistic.” If it is too ambitious, a negative deviation is built into the project plan. Another less obvious and less discussed possibility is that a baseline is too low and could be met too easily. Still, a project would be claimed successful if the baseline were met. From the perspective of the TC-paradigm, this means conceptually that the project manager needs to minimize the negative variation from the baseline, but is not challenged to maximize the value of a project beyond that baseline. There is no empirical evidence about the practical magnitude of this conceptual problem.

The TC-paradigm does not provide a comprehensive perspective for determining project success. It is not sufficient to ask in general which performance criteria are more important than others. This question has to be modified according to the specific circumstances under which a project is implemented, and the needs of the stakeholders. It is the question of which success criteria best reflect project value. For example, time is a very critical success criterion for consumer product development projects, as a delay might lead to significant losses of market share. However, time might not be as relevant for the implementation of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, where it is more important to create a stable and widely accepted solution. Additionally, the project budget can be an important success criterion, because significant cost overruns in a fixed price contract will lead to an overall loss.

The question has to be changed from a generic normative view of determining project success with a general set of criteria and toward a value-oriented perspective. Several authors have addressed this perspective indirectly. For example, the Thames Barrier project took twice as long to build and cost four times the original budget, but it provided profit for most contractors (Morris & Hough, 1987). The success of this project could not be explained with the TC-based approach. In another example, Turner and Müller (2004) suggest that project outcome should be measured and the PM rewarded on a wider set of objectives, not just the achievement of time, cost, and functionality goals. They suggest considering a project's performance evaluation—that is, whether the project created satisfactory benefits for the project stakeholders, was implemented within budget and on time, and satisfied the needs of the end users. Others claim that a successful project should meet two criteria: first, the degree to which the project's technical performance was attained on time and within budget, and secondly the contribution that the project makes to the strategic mission of the enterprise (Morris & Jamieson, 2005). Anton de Wit (1988) considers a project as an overall success if it meets the technical performance specification and/or mission to be performed, and if there is a high level of satisfaction concerning the project outcome among key people in the parent organization, key members of the project team, and key users or clientele of the project effort.

The list of authors addressing project success evaluation could be easily extended. Although the discussions are TC-paradigm centric, the critiques and suggested extensions to measure project success have a common thread: they implicitly point to a different paradigm. It is widely accepted that a project is not necessarily successful if the triple constraint is met, even though most authors see the budget, time, and scope measures as an important part of the general set of project performance evaluation criteria. But some of the discussed concepts demonstrate that it is important for a project to create a certain level of satisfaction. To some extent, this leads away from a satisficing approach and points toward a maximizing paradigm. While satisfaction can be achieved when preplanned value is attained, maximizing goes beyond preplanned satisfaction and ideally leads to enhanced project value (P.V.).

As Definition 1 suggests, project value is not defined in a normative sense. Rather, it is defined in a relativistic sense, as the value of a project could be determined in many different ways depending on its specific context and situation. Determining whether or not the achieved project value represents a maximum is a question that could never be answered accurately. It can only be addressed by evaluating the management process of a project from the perspective of the maximization paradigm. The term “project value” was chosen to clearly differentiate it from the mainstream discussion of project success. A detailed conceptual treatment of the specific conditions determining project value is not essential for the discussion in this study.

Project Risk Definition

Risk and the management of risks is a core concept for project management. It is one of the nine knowledge areas of the PMBOK® Guide. It is not surprising that many authors have defined project risks and project risk management (see Table 1). The analysis of the different definitions is important, as it demonstrates the variety of different perspectives on project risks.

The different definitions are not clear on the subject of impact. Several authors associate risks with both positive and negative effects. We follow the definition of risk offered by general dictionaries and associate project risks with a negative connotation. Positive outcomes or impacts in uncertain situations are often described as opportunities. They will be discussed separately in the following paragraphs. For this book we use the following definition for project risks:

Table 1: Risk Definition Literature Overview

| Risk Definitions | Authors |

| The possibility of something bad happening at some time in the future; a situation that could be dangerous or have a bad result. | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, 2005 |

| Risk is an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on at least one project objective, such as schedule, cost, scope, or quality. | PMI, 2008 |

| Risk refers to events subject to known or knowable probability distribution. | Knight, 1948 |

| Risk is the implication of significant uncertainty about the level of project performance achievable. | Ward & Chapman, 2003 |

| Risk factors are those identified but whose outcome is uncertain. It is defined as “probability times impact.” | Pich, Loch, & De Meyer, 2002 |

| A project risk is an uncertain factor (positive or negative) that can significantly affect achievable performance. | De Meyer, Loch & Pitch, 2002 |

| Risk is the exposure to loss/gain, or the probability of occurrence of loss/gain multiplied by its respective magnitude. | Jaafari, 2001 |

| Known-unknowns are circumstances, outcomes or events that actors have identified as possibly existing, but do not know whether they will take place or not. | Geraldi, Kelley, & Kutsch, 2010 |

The brief literature review above also reveals two main principles of project risk management: the definition of expected outcomes, and the prediction of occurrence and impact of risks. The first principle is a necessary condition for the management of project risks. It is only possible to identify and evaluate risks if project objectives are defined. Otherwise, it would be practically impossible to identify specific events that could influence predefined project objectives. Project objectives are often represented by a project's baseline. Some authors point out that one source for variation is the definition of the baseline itself. If project objectives are not accurately defined, they will be changed over the implementation of a project leading to variations without the occurrence of external influences. Risk management is as much about prevention as it is about reaction or mitigation. Consequently, it is important to establish a realistic baseline to efficiently implement a project.

The second principle is related to the identification of potential events, situations, or conditions that could impact the achievement of the initial project objectives. In addition to the baseline itself, those potential events or circumstances that could lead to a deviation from the baseline and ultimately impact the achievement of project objectives must be identified.

The identification of potential events or circumstances that could lead to a deviation from the baseline and ultimately impact the achievement of project objectives is an important process during the planning stage of a project. The main challenge for risk management is to identify those events that occur with a high likelihood and have a strong impact. The identified risks need to be mitigated to allow for a robust project plan that assures stability over the project implementation process.

Project Uncertainty Definition

The concept of uncertainty is referred to in the project management literature as unknown-unknowns, which indicate specific events that cannot be associated with any probability of their occurrence but can affecting project outcomes. Uncertainty is not clearly addressed by the PMBOK® Guide, where it is mentioned only in one section. The bottom line is that projects are predestined to face uncertainties. Defining uncertainty, Sutcliffe and Zaheer (1998) write:

“Primary uncertainty reflects a lack of knowledge about states of nature, such as the uncertainty regarding natural events, whereas secondary uncertainty reflects a lack of knowledge about the actions of other economic actors.” (p. 3) “We define competitive uncertainty as the uncertainty arising from the actions of potential or actual competitors, which may be either “innocent” or “strategic.” Competitive uncertainty derives from moves or signals by economic actors in current or future competition with the focal firm, which may be “noisy” and difficult to grasp precisely (Porter, 1980). Supplier uncertainty is the behavioral uncertainty arising from the (strategic) actions of the exchange partner firm. Behavioral uncertainty arises from the possibility of ex ante or ex post opportunism on the part of the exchange partner firm.”(p. 4)

Sutcliffe and Zaheer recognize that uncertainty arises from lack of knowledge and that future competitive actions are difficult to foresee. However, other authors—for example, Tatikonda and Montoya-Weiss (2001)—are distinguishing between technological and market or environmental uncertainty: “Uncertainty represents lack of knowledge about the exact means to accomplish the project”(p. 157). This perspective associates information processing with task uncertainty in managing product innovation. The problem is that regardless of the amount of information processing it will never be enough to cope with uncertainty.

Situations representing uncertainties are manifold but yet not explored in detail in the context of projects. The main body of knowledge focuses principally on technical uncertainties.

Project Value Opportunity Definition

Uncertainty is related to unforeseeable project situations, but it does not necessarily lead to a negative consequence. It is argued that the occurrence of uncertainties is a major precondition for the existence of opportunities within an economy (Schumpeter, 1934; Knight, 1948; Kirzner, 1973).The nature and significance of value related opportunities on the project level is not known. However, it is known that specific project situations lead to unconventional solutions, creating value for a project's stakeholders. In general, an opportunity represents the potential for extraordinary value, or, as Schumpeter calls it, “entrepreneurial profit.” In the entrepreneurship literature, entrepreneurial opportunities are defined as: “situations in which new goods, services, raw materials, markets, and organizing methods can be introduced through the formation of new means, ends, or means-ends relationships” (Eckhardt & Shane, 2003, p. 336). Thus, when applied at the project level, the concept of opportunity represents a potential to create value for a project's stakeholders beyond the initial requirements. For our purpose, we view opportunities with a focus on the concept of project value and define project value opportunity as:

Opportunities do not automatically occur; they have to be sought and identified and are related to situations of uncertainty. The relation between uncertainty and opportunity and their management will be discussed further below.

Conceptual Differences Between Project Risk and Uncertainty Management

This study is based on the main assumption that the management of project risks differs fundamentally from the management of project uncertainties. In this section we discuss the conceptual differences between the management of project risks and the management of project uncertainties. The differences might be subtle, but they have significant consequences as to how risks and uncertainties are managed. Some authors (see Table 1) use the concept of uncertainty in their definition of risks. Without a clear distinction between both concepts, it is not possible to differentiate between the various management challenges that are associated with them.

From the discussion of project risks we derive that the main goal of managing risks is to meet agreed project objectives by minimizing the variation from these predefined project objectives that are often represented by the baseline. Risk management aims to identify and then mitigate those risks that are most likely to occur and have high impact on the fulfillment of a project's requirements. This management approach is essential in order to create stability in a highly dynamic process, and to create a more predictable environment. The main challenge for project managers and other responsible project participants is to maintain adherence to the project objectives. This is sufficient only if risks occur. Under these conditions it would also make sense to invest a significant amount of resources and energy to identify all possible causes of risks and mitigate the most important ones.

The problem is the existence of uncertainty. It is basically impossible to foresee all potential causes of project variations. The first management challenge is to accept uncertainty and make a conscious decision about the amount of resources spent to identify sources of variations. In light of uncertainty, it is difficult to determine the appropriate number of resources to overcome this challenge. Furthermore, situations of uncertainty are not negative per se. They will definitely lead to project changes, but they have the potential to improve the initial value proposition of a project. We call this potential possibility to improve the value of a project “opportunity.” The management of opportunities is different from the management of risks. The exploitation of an opportunity requires significant changes that go beyond modifications of a baseline. The management challenge is to question the baseline and find innovative solutions to improve the value proposition of a project. This approach differs fundamentally from minimizing variation around a given baseline. Opportunities require the search for innovative solutions and a mindset for maximizing the value of a project. The management of risk is basically an optimization problem that project managers have to solve. The goal is to meet the initial project objectives with the least amount of variation under specified constraints, like the triple constraint. The constraints are defined by the available resources. If the project results are sufficiently close to the initial objectives and were achieved within the constraints, the project is seen as a success. The main management principle is satisficing. This risk approach stands in contrast to the management of uncertainty. Under conditions of uncertainty it may not be possible to achieve the predefined project objectives. Opportunities have to be identified and exploited to create project value. It is much more a maximization problem that project managers are facing. In a previous study (Lechler & Byrne, 2010), we showed that project managers need to have a mindset to maximize the value of a project. They will only be able to identify and exploit value opportunities if they seek them. We empirically demonstrated that this entrepreneurial mindset is critical for project outcomes.

We could conclude our conceptual discussion by stating that the risk management approach is concerned with managing the variation around the baseline but does not include the notion of maximization; therefore, both uncertainty and risks are similarly treated as threats to achieving the a priori defined project goals. Under the maximization premise, project uncertainties are connected with opportunities and, if exploited, may exceed the predefined project value. Project value opportunities are only recognized, and subsequently evaluated and exploited, if the predefined baseline is fundamentally questioned.

Our own empirical results show that project changes resulting in budget, schedule, or scope improvements are not significantly correlated with project value. In contrast, shareholder and stakeholder value focused opportunities are significantly correlated with project value, suggesting the necessity and importance of studying this phenomenon.