CHAPTER 4

Stories of Success and the Common Good

About the Profiles

What follows is a series of profiles of business leaders—owners, founders, CEOs, and entrepreneurs—who tell the story of the built-together reality. Some of the business leaders profiled herein are people who have worked with the authors for many years through the Responsible Wealth project and United for a Fair Economy. Others are new to us. But in each of their stories is a recognition that their success is not entirely their own. Certainly hard work and creativity played a big part in nearly all these success stories, but so did luck, timing, a wide array of public investments, and an economic framework built through governmental action.

When we interviewed them for this book, we looked beyond questions about their personal characteristics and upbringing typical of many success biographies. Though the questions of modern success biographies have changed with the times, they still focus heavily on character and upbringing as they did in the nineteenth century. As historian Irvin Wyllie noted of these earlier biographies, “many of their questions were routine, but many were prejudicial.”

Was your boyhood spent in the country, or in a city? Did you work as a boy? Did you use tobacco previous to the age of 16? Are you a church member? Is honesty necessary to business success? Should a country boy go to the big city if chances of success are fair in his own community? To what do you attribute your success? What maxims or watchwords have had a strong influence on your life and helped you to success? What books would you recommend to an ambitious boy?1

A modern biographer may substitute illegal drugs for tobacco, but the questions otherwise would be much the same. These questions obviously steer a subject to respond from a framework of individual character. That tradition of focusing on the personal traits while ignoring the contributions of society is a pervasive problem with the success stories told in our culture.

But what if we asked questions that went beyond individual character such as:

![]() What was the role of luck and timing in your success?

What was the role of luck and timing in your success?

![]() Were you born White? Male? Tall? How might that have shaped your prospects?

Were you born White? Male? Tall? How might that have shaped your prospects?

![]() Were you educated in public schools and universities? Were your parents? What about your employees?

Were you educated in public schools and universities? Were your parents? What about your employees?

![]() Did you or your parents get direct government subsidies for higher education, homeownership, or business development? Did you benefit from other government programs?

Did you or your parents get direct government subsidies for higher education, homeownership, or business development? Did you benefit from other government programs?

![]() Did you inherit wealth or opportunities from your family?

Did you inherit wealth or opportunities from your family?

![]() How did you or your business benefit directly or indirectly from public investment and taxpayer dollars or preferential tax treatment?

How did you or your business benefit directly or indirectly from public investment and taxpayer dollars or preferential tax treatment?

![]() What do you believe are your obligations to this society? What are your views toward taxation?

What do you believe are your obligations to this society? What are your views toward taxation?

It was in this spirit that we approached the subjects of the profiles that follow. Most of the profiles are based on original interviews with the subjects in 2011, some of whom were also interviewed in 2003 or 2004 as part of an earlier report. We also included two profiles in this section that are drawn from public records.

We believe that these profiles, taken together, lay the foundation for a more nuanced narrative—the built-together reality—that recognizes successful businesspeople as more than islands floating in a void. Instead it views individuals as acting within an environment rich with public infrastructure built through generations of investment in the common good. The built-together reality credits good ideas and hard work but also points to the roles of timing, other individuals, society, and, importantly, government in supporting business success in this country. As such, the built-together reality leads to the public investment imperative—the idea that all of us, and especially the most successful and financially well off, need to contribute to the support of government to ensure that those public investments continue to be made.

Jerry Fiddler: Public Support for Education Helped Get Me Where I Am

Jerry Fiddler was co-founder, CEO, and chairman of Wind River Systems in Alameda, California. Now a mentor, an investor, and a professor of entrepreneurship, he helps entrepreneurs start new businesses.2

Unless you happen to be a computer programmer, you probably don’t spend much time thinking about how a global positioning system (GPS) or a digital camera works or where the Mars rovers get their intelligence. All those devices have something in common: they’re driven by software developed by a company you’ve probably never heard of—Wind River Systems. Based in Alameda, California, Wind River is a company born in part from government investment in research.

At the helm of Wind River for 26 years—first as founder and CEO and then as chairman—Jerry Fiddler knows that his success depended on many things, including public support of education, other people’s investment, US government support of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, and a whole lot of happenstance. In fact, were it not for a few quirks of fate, he might be a jazz musician, a photographer, or a geologist today.

Wind River Systems was sold to Intel in 2009 for $884 million. Fidder’s share was more than $40 million. Now Fiddler “helps people start companies” as an investor in and consultant to startups in Silicon Valley, as an adjunct professor of entrepreneurship at the University of California at Berkeley, and as guest lecturer and mentor at Stanford University.

Education played an important role in Fiddler’s success. After attending public school in Chicago, he went on to attend the University of Illinois, a land-grant college, where he majored in music and photography.

I was the first person in my family to get a college degree. I went on and got a master’s in computer science. I got out and got a job working at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory as a computer scientist. I was making what seemed to me, at the time, to be an infinite amount of money. But I wanted something different. I wanted to affect the world in a different way. And I decided to start my own little consulting business.

I called my dad, my parents, to tell them, and I was sure they were going to try to talk me out of it because here I was kind of living the dream—I had a stable job, responsible interesting work, prestigious—and I decided I was going to start my own business. I was 29 at the time. And my dad said, “Well it’s about damn time.” It was completely the opposite of what I expected to hear.

In addition to the importance of schooling, Fiddler acknowledges that his entrepreneurship has partially been the result of his upbringing. For him the two seem to go hand in hand: having the opportunity to attend school coupled with the support of family in his endeavors helped lead to his ability to set Wind River in motion. A product of European thinking brought up in America, Fiddler says,

Being in a family situation that supported me to develop, and in schools with teachers who also helped me to learn and develop … you just don’t do it on your own. You do it with the help of parents and friends and teachers and co-workers and service providers.

My parents were both born here, but all four of my grandparents came from various parts of eastern Europe. My dad had businesses: he had a fabric store, a lingerie shop, and that was just the way those folks thought about things; you don’t work for somebody else. The way you grow up and become a real adult or mensch is you start a business, you run a business.

And I think that’s still happening, there’s still that immigrant population that to a disproportionate degree really pushes entrepreneurship. And that population of course relies very heavily on what the public makes available to them, including public education. In turn those new businesses are a crucial driver of our economy.

Fiddler started Wind River Systems as a consulting company in 1978 with his business partner, Dave Wilner, saying, “I don’t think I could have done it without him.” As they moved from consulting job to job, they built pieces of software for their own repeated use; by 1987 Wind River had become a product-based company, focused on selling that reusable software. The company grew very quickly, more than doubling in size each year for six consecutive years and going public in 1993.

Wind River’s software is now found inside everything from digital cameras, to cars and spacecraft, to the routers and the hubs that control the Internet. From a few cutting-edge ideas, Fiddler built a company that provides a critical piece of our technological infrastructure. At its peak in 2000, Wind River had 2,200 employees and was valued at $4 billion.

One of the things people don’t talk about is how much we really rely on government institutions to maintain a fair playing field.

— JERRY FIDDLER

Fiddler attributes his success to a combination of factors. “It’s a wide variety of abilities and a willingness to take risks, coupled with a fair amount of luck.” His ideas about luck have been informed by his varied life experiences:

Something I learned as a musician is that being good is only one of many things you need to be successful. There are a million fabulous musicians out there who are never going to be successful because they don’t have the other skills or support they need. They don’t have the finance, the promotional backing, or the luck.

And business is the same. There are millions of people who have the qualities that make you successful in business but who weren’t lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time or to get the right help. So having the capabilities is necessary but nowhere near sufficient.

To Fiddler a big part of starting a successful business in the United States is the existence of a massive accounting, finance, and legal infrastructure to help companies get started and an education infrastructure to provide the needed skills.

You can have a great idea in most countries in the world, but you won’t be able to find the right advice, or the right accountants and lawyers, and you won’t be able to get it financed. So, part of it is just being in a place where the opportunity exists to start a business. The angel and venture capital community and all the support structure around it is massive and unique; it really doesn’t exist in the same way anywhere else in the world.

There’s no way I would be here if I hadn’t worked at a national lab. It was the best place in the world to learn how to do this. I probably wouldn’t have gotten that job if I hadn’t had a master’s degree, which I got from a public university. I wouldn’t have had that master’s or a bachelor’s degree if there weren’t financial aid and an assistantship in grad school. And had I not gone to a good public school, I probably wouldn’t have gotten into the university. So you just keep stepping back. Heck, if my mother hadn’t had the right prenatal care, I could have been 28 IQ points less intelligent! So where does it start?

Fiddler reflects on how his personal success has been affected by the right circumstances in his life, but he also points to the importance of well-functioning business and financial sectors. The economy functions with rules and regulations that ultimately benefit entrepreneurs and businesspeople. Fiddler believes that many are slow to recognize government’s important role:

One of the things people don’t talk about is how much we really rely on government institutions to maintain a fair playing field. Entrepreneurship is an equalizer, a way that people who aren’t wealthy can become more wealthy, can become more independent, and in the process can provide a huge amount of benefit to society as a whole. But we live in a society right now that is going in exactly the opposite direction. The disparity in wealth between the bottom and the top is growing dramatically, and the middle class is being squeezed out.

All of us, but especially entrepreneurs, rely on the government’s role of creating a level playing field, and people like the SEC and the FTC [Federal Trade Commission] and other regulating agencies are critical to entrepreneurship. Large business interests obviously put huge effort into lobbying, much of it into reducing regulation, but for small businesses, for startups, that regulation is important. The only way that you can have a healthy startup economy is if you have a level playing field that allows those companies to come into being and to compete, and that has to come back to some level of regulation; the government has to be regulating.

Noting the interdependent nature of our economic system, Fiddler continues, pointing out some of the things that most people take for granted:

And then there’s the rest of the infrastructure that we need—the roads and the railroads, transportation and information infrastructure that makes wealth creation possible in this country.

To take it up to a higher level, as a country we are absolutely the envy of the world in terms of the intellectual horsepower we put together—the creativity, the technology, the leadership. Why is that here? To me much of it is a product of the entrepreneurial system and of the immigrants who prized education, learning, and initiative. But most of all, it’s a product of the public education system.

Fiddler is quick to highlight the ways in which he did not create his success purely on his own. From a supportive family with entrepreneurial spirit, Fiddler had the opportunity to pursue higher education and then to begin his own business. As an entrepreneur he’s not afraid to say that he has benefited from governmental regulation. Fiddler is also not afraid to admit that he has been lucky: “It all builds. In this country there is more opportunity and mobility than anywhere else in the world. But it’s very rare that a lot of factors beyond the individual haven’t contributed, a lot of stars haven’t aligned properly to create someone’s success.”

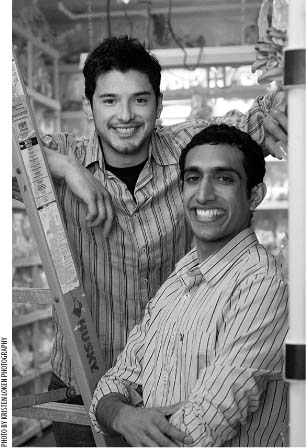

Glynn Lloyd: Transportation and Food Safety Regulations Help My Business

Glynn Lloyd is the founder of City Fresh Foods, a Boston-based food service and delivery company.3

The importance of hard work and a reliable team of advisers is not lost on City Fresh Foods founder Glynn Lloyd. He has taken the lead role from the start but gives credit to his brother Sheldon as well as the people he has relied on over the years, from employees to consultants, for helping to make his business successful.

Lloyd, a leader in the Boston African-American business community, started the business in 1994 with the help of a $20,000 loan from the City of Boston’s Department of Neighborhood Development (DND) to help him build out his first kitchen on Dudley Street. This loan was the money that helped launch the business. By 1998 City Fresh Foods outgrew its Dudley Street kitchen, and the City of Boston helped the company relocate to a vacant foreclosed building that it was able to purchase in nearby Dorchester.

In 2009 City Fresh Foods took on a $400,000 investment in renovating its current 14,000-square-foot building in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, which now serves as its headquarters and production facility. Even with 15 years of success and nearly $5 million in sales, City Fresh Foods’ margins were so slim that it took investments from the DND and the state’s Economic Stabilization Trust as well as a $100,000 equipment lease to make the project work.

Lloyd has worked hard and taken some leaps of faith to make City Fresh Foods what it is today—a company that in 2011 had 80 employees and $7 million in sales—but he is quick to credit the many employees who make the place tick. He also recognizes the role that the public education system plays in making his business possible: “The folks here are mostly all educated through the public school system. The fact that they can read and write and use a computer and all that stuff is pretty important to us. You know, a certain level of education coming in is important.”

A product of the Sharon, Massachusetts, public schools, Lloyd got his start as an entrepreneur back in fourth grade, when he started cutting lawns in his Sharon neighborhood. He soon realized that he could pay other kids $4 or $5 per hour to do the lawn-mowing jobs that earned him $10. By high school he had a landscaping company with two trucks and a team of employees; he was hooked. “I had a knack for numbers and I loved people, so the combination of all those things worked for me.”

Lloyd sees himself as a motivator, capable of bringing out the best in others and of “creating order from chaos.” Where others saw a burned-out building, Lloyd pictured a thriving renovated warehouse with well-trained staff preparing tasty, nutritious, affordable meals and delivering them all around the Boston metro area; he motivated everyone around him to make his dream a reality.

City Fresh Foods operates in what Lloyd refers to as the “public market,” meaning the majority of its contracts are for public school meals and publicly subsidized meals for seniors. While those contracts account for much of the company’s income, it’s in the indirect government investments where it becomes evident how every small business—in fact, every business of any size—relies heavily on public structures.

Well, let’s talk about transportation. We’re a delivery company. We’re going 60 to 70 miles north, east, and south. So without roads, we have no business. We’re using backroads, side roads, and highways. Interesting enough, this was a tough year for us because we do a lot of the schools. Due to the heavy snow, we lost five days of school this year in terms of business, which is unheard of in the past few years. But there would have been a lot more if we didn’t have the infrastructure to clean the streets [and] put the salt down, which I know is very expensive, actually.

Lloyd also talks about the importance of public transportation for his employees to get to work. Though some walk or drive, he notes that many of his employees rely on Boston’s public transit system, including many employees who moved with the company from its Dudley Street location to its current Shirley Street location, about 3 miles away. From a business point of view, urban mass transit systems help expand the pool of employees that companies can draw from in looking for staff to fill their work needs. The state’s investment in the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, including its trains, subways, and extensive bus routes, is a significant benefit to businesses of all sizes that is often taken for granted.

More than most companies, City Fresh Foods relies on natural gas to cook its products and electricity to power its operations; and like many businesses, the company is “completely computer-reliant, Internet reliant,” although Lloyd admits he rarely thinks about those things. Warren Buffett and Bill Gates Sr. talk about what would happen, or rather what wouldn’t happen, if you plunked an entrepreneur down in the middle of a developing country. Lloyd had a taste of that recently, when the Boston water supply was shut down for a number of days:

Water … clean water. We had the issue this year where there was a little concern around water contamination, and they shut it down. We had to pull our water from a different reservoir. And we had to literally boil all of our water here, and it took us back in time. I mean, you talk about taking for granted. I was saying, “What happens if you didn’t have water?” Well, we experienced it this past year. So, those are the basics. We treat it like the air that we breathe, but the reality is, without it, you’re out of business.

Providing health care to employees is one of the most difficult aspects of owning a small business. Massachusetts law now requires that all citizens be insured. City Fresh Foods already pays more than most employers in the food preparation business. It pays half of its employees’ health-care premiums for individuals and one-third for employees with families. “It gets expensive for employees to cover those health costs, the chunk that they have to support.” But Lloyd estimates that half of his employees are using the low-cost MassHealth plan.

It’s funny, because typically as an entrepreneur, you’re not asking for more regulation, but clearly it’s a benefit because people know their food is safe.

— GLYNN LLOYD (left, with his brother Sheldon)

Unemployment insurance as well is very helpful to City Fresh Foods and its employees. Lloyd continues, “On very few occasions, we have had to lay off people here, and during the summer … due to some of our contracts’ seasonality, we have laid employees off for the summer. And I know that’s a lifeline for the folks whom we’ve had to lay off, so there has been a direct benefit to folks.”

And in the food business, Lloyd is well aware that City Fresh Foods relies on food inspections and certifications, both coming in the door and going out: “With qualified vendors coming in, we need to know that they’re handling product correctly, so “USDA Inspected” is one of those things that we look for in terms of our supply side. That’s federal, and then you have your state and your local inspection services, which actually are a stamp of approval to our customers because they know that we’re abiding by basic healthy sanitation practices of how we’re handling our products here.”

These safety standards are not creations of an invisible hand. They are the result of a public outcry and governmental action following the muckraking journalism—including Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle—that exposed unsanitary and unhealthy practices. At the federal level, Congress passed both the Meat Inspection Act and the Food and Drug Act in 1906 to ensure that public health was not compromised.4 Both laws have since been expanded and updated as the industries have changed, ensuring the safety of our food supply for more than 100 years.

“It’s funny,” says Lloyd, “because typically as an entrepreneur you’re not asking for more regulation, but … clearly it’s a benefit because people know their food is safe. And, listen, if we have to do it, we want to make sure our competitors are doing it, and overall it’s trying to protect the health and the safety of our population, our kids.”

Food safety inspections, from the farm to the table, provide public confidence that is essential to any successful food service business.

Lloyd is hopeful that standards for what is served in schools will be changing for the better—away from fats, sugars, and empty calories and toward “real foods,” including leaner meats and unprocessed vegetables. He’s been pushing the city toward reallocating some of its 800 acres of vacant land toward urban agriculture. Both of these changes would help Lloyd and City Fresh Foods do their job even better.

Thelma Kidd: Taxes Are Just the Price of Doing Business

Thelma Kidd is the co-founder of Davis-Kidd Booksellers, which grew to four stores across Tennessee, employing more than 200 people before being sold to another independent bookseller in 1997.18

Thelma Kidd grew up in the West Texas town of Slaton, just outside Lubbock, a dry and dusty part of Texas where rainfall averages only 21 inches per year.19 Her first exposure to entrepreneurship came through her father. “My father was a building contractor,” she says. “He was definitely an entrepreneur, although I wouldn’t have known that word then. He started working for himself very early on, and his philosophy and belief about money—that there is not a paycheck that comes in regularly and that there wasn’t one particular company he worked for—prepared me for being a business owner. Working for myself, that’s really what fits for me—doing my own thing.”

Kidd got her formal education in the public school system of Slaton before going on to study briefly at a private college; she then finished her undergraduate degree at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, a public university. She received her graduate degree in social work from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, another public university, after which she worked for a few years as a therapist.

It was while working as a therapist in Ann Arbor that she saw a new kind of bookstore—the original Borders Books. Later she moved to Tennessee, where she joined with her college friend, Karen Davis, to explore the idea of starting such a bookstore in Nashville. Kidd’s love for bookstores, more than the idea of “starting a business,” motivated her. Specifically, she wanted to create a bookstore that honored free thought and differing opinions: “I liked the idea of having a magazine rack where two people could be standing side by side, and one could be reading the Buddhist Review and the other Christianity Today, and those people would both be welcome in the store. To me that is progress.”

Meanwhile, in Washington, DC, big changes were under way that would have a major impact on Kidd and Davis’s business plans. Julie Weeks of the National Women’s Business Council writes of the events that led up to President Jimmy Carter’s signing of Executive Order 12138:

Women have started, owned and inherited businesses in the United States since the founding of the country, yet official recognition and support for women’s enterprise development has been in existence only for the past 25 years …

The first federal government program to assist women’s business enterprises came as the direct result of lobbying from women business owners. Due to their efforts not only in lobbying the federal government but in urging the appointment of women in key agency positions, an interagency government task force was created, and a research study was conducted to review the status of women-owned firms in the US. The resulting report, “The Bottom Line: Unequal Enterprise in America,” documented some of the barriers that women faced in starting and growing their businesses. In response to the report, President Jimmy Carter issued an executive order in 1979 establishing an Office of Women’s Business Ownership within the US Small Business Administration.

Shortly thereafter, a pilot loan program was established, the office began working with federal procurement officials to get more women-owned businesses involved in selling goods and services to the government, and began reaching out to the women’s business community through speeches, conferences, and news releases.20

It was in 1979, the same year the executive order was signed and a year before their business formally opened, that Kidd and Davis received one of these new Small Business Administration (SBA) loans for women entrepreneurs. They scraped together about $50,000 of their own, mostly borrowed from relatives, which was matched by a $175,000 SBA-guaranteed loan. Kidd notes, “It was a bank loan; but the SBA guaranteed if we defaulted that the bank would get 90 percent of their funding back from the SBA.” This guarantee helped Kidd and Davis overcome some of the major hurdles they faced as women starting a business.

I agree with something one of my mentors said: “I want to pay a lot of taxes, because that would mean I’m making a lot of money.” It is fair.

— THELMA KIDD (left, with her daughter and granddaughter)

“It was challenging being women going into business because there was a lot of resistance from Realtors,” says Kidd, “and we weren’t taken as seriously as I think we would have been had we been male. On the other hand, there was this funding available that was to encourage women to go into business, and that helped; that really was a great boost. I don’t know that we could have done it without that.”

Expanding on the challenges of being taken seriously as women entrepreneurs when approaching banks, Kidd adds, “We would have stunned looks or blank stares that would come back at us when we talked about what we were planning to do. The bankers and Realtors assumed that we were not serious about it, that we would get tired of it after six months and quit. I don’t think they assume that about a man who walks in.”

Thanks in part to the SBA-guaranteed loan, they overcame these challenges and opened their first store in the Green Hills neighborhood of Nashville in 1980. It was busy from the very beginning, which Kidd attributes to great timing and a bookstore model that was new to Nashville. Instead of the typical small bookstore with 2,500 titles, the new Davis-Kidd Booksellers had closer to 25,000 titles in their large, 3,500-square-foot store. Later they moved and expanded again to 9,000 square feet. The store eventually grew to 25,000 square feet and more than 100,000 titles.

They also tried other new strategies, such as staying open at night and seven days a week. This was pushing the boundaries far out for a Nashville bookstore in 1980, but it paid off. Within a few years, they opened up additional stores in Memphis (1985), Knoxville (1986), and Jackson (1995). When they finally sold the company to another independent bookseller in 1997, they had more than 200 employees and four stores, three of which included cafés.

Kidd acknowledges the importance of timing and luck, in addition to hard work, saying, “Things turn in your favor periodically, and it’s not just because you’re a good person or you worked hard, because things go against you sometimes, too, and it’s not because you are a bad person or you weren’t working hard. I do think that people who are successful need to be really dedicated and committed and have vision. But that alone is not enough. You need things going your way periodically.”

Kidd also talks about the importance of public investments and the stable regulatory environment in supporting her business. She acknowledges the role that public schools, libraries, and safe communities have played in her own life, but also talks of the benefits her stores received: “Obviously, when you have a retail store or any kind of public place, people are going to come in and use your space. I’m glad there were building inspectors and health inspectors for the café. It’s like a third-party check on what we were doing. That we had access to those people with the knowledge to keep our facilities safe was actually helpful, and it protected us.”

As Oliver Wendell Holmes once declared, “Taxes are the price we pay for civilization.” Kidd’s view on taxes is similar, noting that it’s just the price of doing business:

I don’t remember feeling resentful of having to pay taxes or having to pay for all the various licenses that you have to pay for. I mean, it is a hassle, it is money, but it’s business. It’s part of the price of doing business …

If your business doesn’t generate enough for you to be paying the various things you’re supposed to be paying, then your business model doesn’t work. You know, you need to do something different. You need to adjust something. That just feels like energy that is so wasted, to be mad at the government…

I agree with something one of my mentors said: “I want to pay a lot of taxes because that would mean I’m making a lot of money.” It is fair.

Warren Buffett: This Society Disproportionately Values What I Do Well

Warren Buffett founded Berkshire Hathaway and lives in Omaha, Nebraska.

Warren Buffett, the founder of Berkshire Hathaway and the second-wealthiest man in the United States, is hailed as one of the most successful stock market investors ever.21 Yet this does not prevent Buffett from acknowledging the role of the uniquely fertile soil of the American economic system in amassing his wealth. At a 1996 Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, Buffett noted that the US system “provides me with enormous rewards for what I bring to this society.”22

Although we referenced the following quote in the introduction, it is worth repeating here. In a television interview, Buffett stated: “I personally think that society is responsible for a very significant percentage of what I’ve earned. If you stick me down in the middle of Bangladesh or Peru or someplace, you’ll find out how much this talent is going to produce in the wrong kind of soil. I will be struggling 30 years later. I work in a market system that happens to reward what I do very well—disproportionately well.”23

Buffett feels he is not only fortunate to have been born in the United States but also lucky that he “came wired at birth with a talent for capital allocation.”24 He bought his first stock when he was just 11 years old, from which he made a $5 profit. When his family moved to Washington, DC, from Omaha, Buffett had two paper routes, earning him $175 per month; he also had a business that made $200 per month from pinball machines and peanut vending machines.25 After graduating from Woodrow Wilson High School, Buffett attended the University of Pennsylvania for two years before transferring to the University of Nebraska. He later earned his master’s at Columbia Business School.26

Upon graduation Buffett worked as an investment salesman in Omaha for several years before taking a job at the Graham-Newman Corporation in New York. He returned to Omaha in 1957 and began Buffett Partnership Ltd. In 1962 his partnership bought shares in a textile-manufacturing firm called Berkshire Hathaway; he eventually took control in 1965 and used the company as a means to invest in others. Since then Berkshire Hathaway has acquired stock in such corporations as the Washington Post Company, ABC, Coca-Cola, and Gillette, and it even owns various companies, such as GEICO and FlightSafety.27 His successful investing strategies, which follow a value investing philosophy, made Buffett a millionaire and eventually a billionaire. He is currently the chairman, CEO, and largest shareholder of Berkshire Hathaway.28

I think that people at the high end—people like myself—should be paying a lot more in taxes. We have it better than we’ve ever had it.

— WARREN BUFFETT

But Buffett recognizes that while his particular skills have been and continue to be highly valued in the marketplace, the skills of other people are undervalued:

If you’re a marvelous teacher, this world won’t pay a lot for it. If you are a terrific nurse, this world will not pay a lot for it … I do think that when you’re treated enormously well by this market system, where in effect the market system showers the ability to buy goods and services on you because of some peculiar talent—maybe your adenoids are a certain way, so you can sing and everybody will pay you enormous sums to be on television or whatever—I think society has a big claim on that.29

Consequently, Buffett’s attitude toward society shapes his perspective on taxation. He has said, “If you’re in the luckiest 1 percent of humanity, you owe it to the rest of humanity to think about the other 99 percent.”30 Thus, Buffett is a staunch advocate for progressive taxation to “partially redress” existing inequality.31

He pointed out that in 2011 his taxable income of around $46 million was taxed at only 17.4 percent, a fraction of what others pay.32 He believes this is unfair. In a recent interview with ABC, he detailed his feelings: “If anything, taxes for the lower and middle class and maybe even the upper middle class should even probably be cut further. But I think that people at the high end—people like myself—should be paying a lot more in taxes. We have it better than we’ve ever had it.”33

Buffett is also an advocate for the estate tax. In 2007 he testified before the Senate Finance Committee about its importance: “Dynastic wealth, the enemy of a meritocracy, is on the rise. Equality of opportunity has been on the decline. A progressive and meaningful estate tax is needed to curb the movement of a democracy toward plutocracy.”34

In addition to supporting policy measures that address gross inequalities of our economic system, Buffett is a well-known philanthropist. In 2006 he announced that he would give away all of his Berkshire Hathaway stock to philanthropic foundations, with most of it going to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Then, in 2010, Buffett pledged to give away 99 percent of his wealth during his lifetime or at his death because, as he put it, “fate’s distribution of long straws is wildly capricious.”35

Martin Rothenberg: My Success Was Paid For by Others

Martin Rothenberg was founder and CEO of Syracuse Language Systems, based in Syracuse, New York.36

Martin Rothenberg forgets neither where he came from nor the help he received along the way. Now a successful entrepreneur in Upstate New York, Rothenberg is quick to credit the many public resources that were available to him.

Rothenberg’s story begins in Brooklyn. The son of immigrant parents—a housepainter and a sales clerk—he attended public schools there. Says Rothenberg: “I started my movement to technology by going to the Electricity and Radio section of the local public library when I was maybe 12 or 13 years old. I picked out all the books on that subject, and I found one that I thought I could understand without any help. I just read it from cover to cover.”

In a New York City technical high school, he took his first formal classes in technology. But money for college was not in the family budget: “If I went to college, I would have to pay for it myself. I could never take money from [my parents] for a college education—that wouldn’t be fair. That would come from the savings they had for their retirement.”

Following high school Rothenberg put his technical skills to use doing television repair, and he considered opening a shop of his own. But he was drafted into the army in 1953, and after Signal Corps training he spent 14 months in Korea. As the end of his tour of duty approached, Rothenberg recalls learning about what the GI Bill offered: “When I got home, they were offering me a full scholarship, including tuition and a stipend to live on. You’d have to be foolish to turn it down. By making it easy to attend college, the GI Bill encouraged people to make that step, to give up the immediate income for possible gains in their lifestyle and financial status later on. That’s what it did for me.”

After graduating from the University of Michigan in electrical engineering, Rothenberg took a job with Hughes Aircraft, then another in the space program at Bendix. His wife’s degree program took him back to the University of Michigan, where he learned about a full fellowship for a new three-year graduate program that combined computers and language. He notes that the fellowship program was under the National Defense Education Act, a direct result of the Russians’ launching the Sputnik satellite, as the country realized that there were not enough Americans educated in the area of technology. He was accepted into the program and had a necessary fourth year of graduate work funded by a loan, forgivable on the condition that he go into teaching.

The forgivable loan biased me somewhat toward going into education. I think that most people don’t realize the extent to which the technology programs at the universities are sponsored by the government. Besides the sponsorship of my education, I had research grants all the way through my teaching career, starting from the first year. There were a couple of grants from private foundations, but mainly they were government grants.

Besides paying for part of my own salary and lab equipment, the grants included tuition and stipends for assistants. So the young people who work for you in your laboratory are mostly paid for by the government. My university research provided the basis for Syracuse Language Systems. So that’s in large part where my wealth came from.

After graduate school, he went on to teach at Syracuse University for 25 years, from 1966 to 1991.

After the death of his wife in 1990, Rothenberg retired and started Syracuse Language Systems, which developed multimedia software for language learning. Of the company name, he says, “The reason I called it ‘Syracuse’ was because it was the Syracuse area that had all the skills necessary to make a high-tech software company. We had talented artists, programmers, marketing specialists, and linguists for the language software. And, of course, most of those people were educated in our public education system.”

He started the business slowly, with just a few people, including his son, starting out in a government-sponsored “incubator” that provided below-market rent and subsidized support services.

I had the ability, which was given to me by my graduate studies, to understand what’s right and wrong in speech patterns and, from my engineering experience, how to measure that and give corrective feedback to people. So I have those technical capabilities, which are not commonly found in one person. Usually, someone is either a linguist or an engineer, not both.

When I left the university in 1991, some people thought I, as an academic, could not do well in business.… They didn’t know my grandmother. My grandmother was an entrepreneur who was always in business even though she couldn’t read or write English, at least not too well.

By making it easy to attend college, the GI Bill encouraged people to make that step. That’s what it did for me.

— MARTIN ROTHENBERG

As a software developer, the company relied heavily on patent and copyright law to protect its products. Says Rothenberg:

Intellectual property protection is important. You can’t accumulate a lot of money or resources without someone stealing it from you, and a government has to protect you and stop that from happening. I have a number of patents. In my present company [Glottal Enterprises], for example, it would be easy for a larger company to reproduce what we are doing, except for the fact that I do have some patents protecting a lot of what I am doing now.

Syracuse Language Systems was the first company to make a consumer product using computer-based speech recognition, and I was awarded a patent in that area that protected our innovation. At a financially crucial time, we were able to get a sizeable legal settlement from one company that was copying our programs in Japan. On the other hand, one reason we couldn’t go into China was because they didn’t enforce copyright laws.

Not only was Rothenberg able to rely on the US government to protect his product but he also gives credit to the government for starting the Internet. “In the last years of our ownership of the company, we were heavily invested in using the Internet for language instruction.”

That’s not to say that the government couldn’t do more to support small businesses and level the playing field. Rothenberg reflects on some of the challenges faced by small businesses in America: “For example, one problem in hiring [at] a small company is health care. It is hard for us to pay for health care. Government health care, at least minimum health care, would make that better for us.”

In addition to his technical and linguistic skills, Rothenberg sees his strength as an entrepreneur as setting a clear vision for the company that everyone understands, motivating people, knowing his own limitations, and bringing in the right people to help him. But he’s quick to point out that he didn’t—in fact, he couldn’t—do it alone:

You can’t have a company doing especially high-tech work without a network of people that you can draw on—skills that you can draw on—for technical management [and] marketing skills. There is nothing that I could have done alone. My father was a house painter; all he needed was the paint and he would get paid for painting somebody’s house. But you can’t build a high-tech company by yourself in that way.

The first thing that you have to do is gather a team. There’s not much you can do as one person. You could start a small retail business, like my daughter has, but you’re not going to make a lot of wealth that way. Generally, you have a team. Unless you can find 76 hours in your workday, you just can’t do everything yourself.

When Rothenberg and his financial partners eventually sold Syracuse Language Systems in 1998, it was worth approximately $30 million. With a part of his portion of the proceeds, he established a small family charitable foundation dedicated to children, education, and the environment.

He does not forget the people who made his success possible. Together with most of the other stockholders, Rothenberg gave a parting bonus to the company’s long-term employees. He adds, “I consider grants from the charitable foundation to be in some measure from all the personnel of my former company, with my family acting as trustees.”

Kim Jordan: The Idea of a Self-Made Person Is a Stretch

Kim Jordan is a co-founder and the CEO of New Belgium Brewing, the nation’s third-largest craft brewer.50

Established in 1991, New Belgium Brewing is the maker of the popular Fat Tire beer, among many others.51 Since its founding, the Fort Collins, Colorado–based company has grown rapidly. It is now the third-largest craft brewer in the nation,52 with more than 400 employees, including 250 in Colorado and another 150 across the nation. At the company’s helm is CEO and co-founder Kim Jordan.

Jordan makes clear her view of the self-made myth: “This whole notion of the self-made person is a stretch.… If you live in a farm community, which I have done, you see that neighbors are wildly dependent on one another: ‘I’ll come help you put up your hay; you’ll plow my road.’ It is certainly more of a myth than a reality, and that’s just the interpersonal part. You know, one neighbor to another.”

Expanding her example to the role of government, Jordan adds:

Then you have the whole, “Well, wait a minute. How about all of the subsidies for farming, or the county road system, or the fact that school buses drive long, long ways out of the way to pick kids up to be able to attend public school?” You know, it seems like the purpose of the government is to be able to fund things that we can’t fund … by ourselves because it’s just too expensive to do.

So [the myth] has a lot of romance to it, I guess. Although I’m not quite sure why we feel compelled to say that we don’t need to rely on one another.

Jordan speaks highly of the public investments, coordinated through the Downtown Development Authority (DDA) that have revitalized downtown Fort Collins, where New Belgium Brewing is based: “The quality of life in downtown Fort Collins is much improved because we have a Development Authority that’s able to use tax increment financing to make really cool projects downtown that are vastly improving the cultural vibe of the community.”

Small and large cities across the United States have such a development authority that works to “foster economic, cultural, and social growth”53 in their downtown areas. In 2010 the Fort Collins DDA renovated two alleys, stringing up lights, planting flowers in pots, and utilizing quarried boulders as benches. The DDA has also helped fund the improvement of more than 70 facades in Fort Collins, simultaneously promoting “green building practices and projects,” which the 2010 DDA Annual Report says attract green businesses that are more likely to fund community projects.54

Jordan reflects on the many public investments made possible through our tax system that have helped New Belgium succeed: “Beer is heavy, and it needs to be transported in vehicles. Certainly the public highway system, the federal system, has been hugely important to [New Belgium Brewing].… We are in an enterprise zone, and so the credits we receive for that, both in hiring and in investments, have been important. The tax credits for purchasing equipment have been really helpful to us, and we probably would not have been able to grow as we have without those because there were years when they were pretty significant.”

Beer is heavy, and it needs to be transported in vehicles. Certainly the public highway system … has been hugely important to New Belgium Brewing.

— KIM JORDAN

In the crucial early years of the operation, New Belgium received a $40,000 Small Business Administration loan. “We were probably three years into it [the business] … so at the time, that was pretty substantial.” The company also benefited from services provided by the local land-grand university, Colorado State University (CSU), and a grant from the Department of Energy to encourage innovation and new energy technologies.

We work a lot with CSU in pilot programs where they want a test facility for some project or another. So just the fact that we have a land-grant university in our town is helpful to us, all the way from microbiology through energy management.…

We are part of a test project, a grant through the Department of Energy.… Being a part of that project, on the one hand it compelled us—or rather forced us, I guess—to invest a few million dollars, but on the other hand we were able to get a couple of million dollars out of the program as well for both hardware and software for energy management and for renewable energy production. So that was a benefit.

Like almost all business owners, Jordan took great risks in her life. She and her then-husband took out a second mortgage on their home, along with credit card debt, to raise the seed money they needed to start the business. At one point she had to borrow $5,000 from family to make payroll, but in the end she emerged a very successful businesswoman.

Jordan acknowledges that she was also lucky on many levels. Both of her parents were college graduates who were politically active and engaged in the community. In addition to providing a stable home environment, her parents could afford to send her to a private Quaker school, where she learned some of the bedrock values she holds to this day and which have influenced the company as well. Says Jordan: “George Fox, who was one of the founders of the Quaker movement in the United States, has a quote, which is, ‘Let your life speak.’ And in terms of the way that we operate New Belgium, I think that’s been really influential for me because I think one of the things that you come to see as a successful entrepreneur is that you can use profits to do really interesting work.”

Jordan benefited in many ways from the public structures in our society. She completed her college degree at CSU, a land-grant college as noted above. While she worked her way through college, she received publicly guaranteed student loans and a few Pell Grants along the way. Jordan was also fortunate to have attended CSU at a time when the state was far more generous in its support of higher education.

During the years that Jordan attended CSU, higher education accounted for more than 20 percent of the state’s general fund budget. That dropped to just over 10 percent in the years leading up to the Great Recession in 2008. Since then it has dropped to only 6.4 percent of the state’s general fund budget, though funding from ARRA has helped offset some of the funding lost during the past two years.55 Absent a new stimulus plan, however, that federal assistance will soon disappear.

Recognizing all the benefits and good fortune that both Jordan and New Belgium Brewing have received over the years, Jordan takes to heart a quote from Luke 12:48, “For everyone to whom much is given, of him shall much be required.” And giving back is a fundamental aspect of how New Belgium operates:

It’s about making sure that we pay a living wage, sharing profits with our co-workers, sharing equity through ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan) ownership, giving people a bike, providing domestic partner benefits, having paternity and maternity leave, having a generous personal time-off plan—I could go on.… [This set of company policies] comes from the belief: (1) that to whom much is given, much is required, (2) that excessive consumption is really not the best mark of a life well-lived, (3) that the pooling of labor to build equity should inure at least at some level to the benefit of everyone, and (4) that the accounting for our impact on the commons is our responsibility to work toward.… I’d never want to sit here and say, “Oh yeah, we account for all of our impact”—because we don’t. But we understand it to be a process, and we are into continuous improvement, so in that area as well as many others we continue to invest money and intellectual energy and passion and focus.

We lift up a pint in celebration of Jordan’s uncompromising values and business success.

Anirvan Chatterjee: Leaving the Ladder Down behind Him

Anirvan Chatterjee is the founder and the CEO of BookFinder.com, which later became a subsidiary of Amazon.com.56

Anirvan Chatterjee didn’t set out to found a successful online business as a young technologist in Silicon Valley in the 1990s, but it almost seemed inevitable:

I’d been running the site as a hobby project out of my dorm room, and it started growing, gaining users. Meanwhile it felt like everyone around me was trying to start their own dot-coms. I don’t have an entrepreneurial background in my family. But the entrepreneurial dream was totally a part of San Francisco Bay Area culture during those early dot-com years, with everyone reading their Wired magazines and talking about how the Internet would change the world. It was hard not to get caught up.

The result was BookFinder.com, a comparison search engine for new, used, rare, and out-of-print books that the then-19-year-old Chatterjee first built as a class project at UC Berkeley and which eventually became a subsidiary of Amazon.com.

A similar environmental boost came from his family: his father, who had emigrated from India to Canada and then moved to the Bay Area, was an engineer.

I started programming when I was 15. My dad worked tech jobs, and he was able to bring a computer home from his work on the weekends, until we bought our first computer. My parents had moved so that I could go to school in a well-funded public school district. Property prices were higher, but they made that sacrifice for my education. I started taking computer science classes at school as early as possible. We had a great computer science teacher, and she really sparked my interest in trying to think about how people use technology.

In fact, state-sponsored education played a multigenerational role in Chatterjee’s success. The Indian government trained his father (and thousands of others) in engineering, ultimately helping fuel technological advances in the United States and elsewhere. Once the Chatterjees came to America, California’s public schools nourished and focused Anirvan’s nascent interest in computers.

When Chatterjee was trying to decide whether to take his entrepreneurial leap from college to business, he sought and received the encouragement and the blessings of his mentors at UC Berkeley, the flagship university of California’s public higher-education system. “The support of my professors meant a lot to me,” he says. “Many of them had seen me start the project as an undergrad and continue working on it as a grad student, seeing the site grow, seeing it get national attention. It meant so much to get that kind of support from them, letting me use the site as an example project in my classes.”

Before the Internet, finding rare books was a hit-or-miss affair of hours spent searching the dusty stacks of mom-and-pop stores. The digital revolution allowed individual retailers to widely share their catalogs, but comparison-shopping was still difficult. That was the problem BookFinder.com was created to solve. “There were over 50 different sites where individual bookstores could upload their catalogs,” says Chatterjee. “What BookFinder.com offered was a one-stop search. As a user you would type in the name of the book you wanted, and we’d instantly search millions of books for sale and show you all the choices, so you could pick the cheapest copy or a signed first edition or whatever you wanted. You could then buy the book of your choice directly from the bookseller.”

Public investment in libraries served as a source of inspiration:

If it weren’t for libraries, I may not have been reading so heavily or have gotten into the bookselling business. Growing up, my parents would take me to the library every week, and I got so much joy in being able to check out any book I wanted. I’m a voracious reader. I read over a hundred books a year. The mix has changed over time. After I started working, I started buying more of those books, and now the mix is about 50-50. But libraries sustained me to the point where I started taking buying books seriously enough that I could start a business around it.

Chatterjee stayed with his company after it was bought out—first by used-book search giant Abebooks and then ultimately by Amazon.com—but he left in 2009, after almost 13 years at the helm, to spend the next year doing citizen journalism with his wife, focusing on global climate change issues.

Chatterjee attributes his success to factors beyond talent and hard work: “Being there at the right time, at the right place, with the right idea had a lot to do with it. I mean, I worked hard. I don’t want to discount the fact that I worked incredibly hard on my startup. But a lot of people work incredibly hard on their ideas, and people work hard all their lives and don’t necessarily have much to show for it financially at the end of their lives. So I count myself as incredibly lucky.”

Ironically for an American story, even Chatterjee’s brown skin helped him: in the world of Internet startups, his Indian-American ancestry gave him the reassuringly “right look” for a computer programmer in Silicon Valley. “My race and gender certainly didn’t hurt,” he says.

He also cites hard-to-measure yet still very real “public goods”—such as the enforceability of contracts—as part of the environment that allowed his business to thrive:

As a really young company, we’d end up juggling 50 to 100 contracts at any given time with companies in the book space. In many cases, we would contract with a company so that they would have their books listed on our site at no cost, and they would pay us something if and only if we helped them sell any books. But we couldn’t really know if we’d helped sell any books or not. Once our users left our website, we had no way of knowing if they completed the transaction. But we trusted those contracts. It meant a lot to be working in a stable business environment in a first-world country, where we felt like we could rely on partners to honor contracts.

Similarly, just as his company relied on the established legal framework and the centuries of contract law and practice to undergird its business relationships, as a programmer Chatterjee is well aware that he was able to draw from the commons to design and engineer his website. “We didn’t have to write 99 percent of the code for the BookFinder.com platform,” he says. “We built on top of an open source operating system, databases, programming language, and code libraries. Thousands of programmers had banded together to build great software and give it away at no cost. That meant we didn’t have to spend $50,000 buying a license from Oracle—we could download a free database and get started building a company, thanks to a generous sharing economy.”

It meant a lot to be working in a stable business environment in a first-world country, where we felt like we could rely on partners to honor contracts.

—ANIRVAN CHATTERJEE

Just as he acknowledges the role of good luck in his success, Chatterjee recognizes the bad luck that can trip up others. A supporter therefore of public services that give a necessary hand up, he bemoans the recent “massive disinvestment” in the California public education system that served him so well:

That [disinvestment in public education] starts at K–12 and goes all the way up to our two tiers of public universities and community colleges. And having started a business that came out of a university class project, it seems only fair that others have that same opportunity to access a space that could be an incubator for every Californian with a great idea. I didn’t think I’d start a business—I just happened upon it. I was at the right time and place but in an environment where I was inspired to go further. And I really hope that’s going to be as accessible as possible to a large, diverse audience.

He says that California’s public universities are addressing funding shortages by filling classrooms with more full-tuition, out-of-state students, leaving fewer slots for local students whose education is partially subsidized by the state: “Our taxpayer dollars should be supporting more in-state students getting this kind of public education. It’s not only for those who can pay more.… Yeah, I’ve gotten a lot and I want to make sure others have that as well.”

On a national scale too, Chatterjee thinks it’s simple logic that public services be paid for by those best able to bear the cost—people like him, who often have been the beneficiaries of those services:

I’ve been incredibly lucky, building and selling a small dot-com in my twenties. Especially in a recession like this, people like me are the first ones who should be tapped to make sure that the country’s able to pay for its basic human needs.… So, yeah, I am very much in favor of substantially increased progressive taxation, possibly a tax on wealth or a tax on financial transactions. There’s a huge class of Americans who can afford to be tapped a little bit more so we can pull everyone else up with us.

Chatterjee believes in leaving the ladder down behind him.

Peter Barnes: Wealth Comes out of the Commons

Peter Barnes co-founded Working Assets and is currently a writer and an entrepreneur in Point Reyes, California.64

Peter Barnes co-founded Working Assets, a financial services and telephone company serving progressive investors and consumers. Like his parents, Barnes attended New York City public schools, and “the fact that my father, a penniless son of immigrants, could get a really good free education certainly benefited me.” After graduating from Harvard in 1962, Barnes worked as a journalist for 15 years and then decided to become a businessman. In 1982 he co-founded Working Assets as a socially responsible investment firm that later moved into credit cards and telephone service. He sold his stock in Working Assets to his partners and retired in 1995.

His experience as a business owner led him to co-found OnTheCommons.org, an organization dedicated to expanding popular understanding of the “commons,” which includes, in Barnes’s words, “the gifts of nature and society that we share and inherit together—and have an obligation to pass on to our heirs, undiminished and more or less equally.” This notion of the commons includes environmental assets such as the air, fisheries, water, and land. It also includes socially created assets such as our highways, legal system, the Internet, and accumulated scientific knowledge.65

Barnes’s understanding of the role of the commons has shaped his perspective about wealth creation. The notion that stock values are in part socially rather than individually created will be new to most readers. It comes from his experience taking (or rather almost taking) Working Assets public:

What we, the private shareholders, learned was that our business was worth a whole lot more as a public company than as a private company. What added this extra value? It wasn’t that we’d make more sales or profit—these numbers would be the same either way. The extra value came purely from the fact that our stock would be liquid—we could sell it to any Tom, Dick, or Harriet, any day of the week. According to our investment banker, liquidity alone would add 30 percent to the value of our stock.66

Though in the end they decided not to take the company public, for Barnes it was a pivotal lesson. “That added value comes not from the company itself but from society—from the stock market and the infrastructure of government, financial institutions, and media that supports it.” For many whose wealth has been created in the stock market, it is easy to forget that this entire system has been built over several generations and is regulated at taxpayer expense through institutions such as the Securities and Exchange Commission.

And the US stock market is not just local. It is a highly sophisticated global marketplace where you can sell your shares virtually anywhere at any time. This gives access to an infinitely larger market of potential buyers—the market for shares becomes the whole world. This greatly increases liquidity and value. As Barnes points out, “You are plugged into a global network; you get listed, and based on your filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, people generally believe your numbers. You talk to a few analysts and, sight unseen, they pay you money. It’s a wonderful social creation that basically rewards private shareholders for adding their company to the grand casino that is the publicly traded stock market.”

For Barnes the stock market is just one of the ways in which a private enterprise benefits from society’s investment and infrastructure. The entire system of institutions that fosters trust in the marketplace is essential. When Barnes co-founded Working Assets as a money market fund, he created advertisements to attract investors: “The next thing we knew, people were sending us big checks in plain envelopes. These people had never seen me before, nor met anyone from our company. They didn’t know us from a hole in the wall. So they didn’t trust us. They trusted a system that took centuries to build. I wrote some ads, but no one would have responded to them without the whole infrastructure that gave people trust.”

Repeated examples show what happens when this trust in the marketplace is shaken. In the wake of the Enron and WorldCom scandals, millions of investors lost confidence in the accuracy of corporate accounting, and the stock market lost 28 percent of its value.67 A study by the Brookings Institution estimated that the decline in investor confidence cost the economy approximately $35 billion.68 “The corporate scandals caused people to stop trusting the numbers that companies were reporting,” said Barnes. “Imagine how much value is created by trust and the whole system that assures that trust?”

People were sending us big checks in plain envelopes.… They didn’t know us from a hole in the wall. So they didn’t trust us. They trusted a system that took centuries to build.

—PETER BARNES

Since leaving Working Assets, Barnes has focused his energies on writing about economics and the commons. He is the author of Who Owns the Sky?, a book proposing a solution for environmental degradation and economic inequality called the “sky trust.” Recognizing the air as a common asset that absorbs pollution, Barnes calls for using the proceeds from selling pollution rights to fund wealth-building accounts for everyone. He helped write “cap and dividend” legislation that would charge polluters and return the revenue to everyone on a one-person, one-share basis. Barnes believes this would curb global warming and ensure a strong middle class at the same time.

Barnes is an advocate of a healthy capitalism that recognizes the value of the commons. This value is huge and lies behind much of what we call “private” wealth. “Most wealth comes out of the commons,” he says, “and individuals add a little bit on top of that. But because of the way capitalism is set up, for adding that little bit, you get to grab an enormous share of what comes out of the commons.”

This description by Barnes reflects what we mean when we talk of the built-together reality of individual and business success. In our case, we’re speaking primarily of the public infrastructure, built through generations of public investments in the common good. Whatever the entrepreneur adds is built on top of that foundation.

For Barnes the challenge of capitalism in the twenty-first century is to recognize the value that is created by the commons and to protect it—give it standing and clout. There will still be those who generate substantial individual wealth, but it won’t be because they have pocketed the wealth of the commons.69

Amy Domini: Regulation Makes My Industry Possible

Amy Domini is founder and president of the Domini Social Equity Fund, creator of the Domini 400 Social Index, and founder of the Domini Social Investment mutual fund.70

Amy Domini questions a lot of things. She challenges the status quo on a regular basis; in fact, questioning the status quo forms the basis of her groundbreaking business. But ask her to point to the influences that made her an entrepreneur, an advocate, a pioneer, and a challenger, and she’ll tell you it was the public structures and the predictable social order of small-town 1950s childhood in suburban Connecticut that instilled in her a sense of safety, clarity, duty, and service. “Everybody went to Girl Scouts,” she says. “Everybody went to church and Sunday School. Everybody learned how to figure-skate; everybody learned how to swim.… If you didn’t want to go stir-crazy, you were always interacting with other people.… In my mother’s generation [it was] creating a bridge club or a PTA [Parent/Teacher Association].”

One of Domini’s lessons about the role of public investment came early. She was the daughter of a public school teacher and the owner of an eggplant processing plant. Domini recalls, as a teenager, her parents pressing their fellow taxpayers to approve a tax levy to build a new high school. The levy failed and the new school was not built, leaving the students to suffer in a dilapidated building. “It was one of the first times I made the connection between paying taxes and the quality of life.”

Her path to becoming a broker in a male-dominated industry was not without help but also not without hard work. With the help of her grandfather, she got a job as a clerk, making copies at a brokerage firm. Using the lessons from her childhood, she arrived five minutes early to work and meetings, did a little bit more than asked, and eventually got promoted through the secretarial ranks. In 1974 she recalls that the stock market was “in the tank”; and although most brokers at the time were men, she asked her boss if she could take the training and to her surprise soon became the firm’s first female broker. She later learned that four women had sued Merrill Lynch for gender discrimination and realized she was probably an indirect beneficiary of those women’s exercising their rights.

In those days, she says, stock ideas would often come “over a squawk box from some smart person in New York” and then be passed on to clients to see if they wanted to invest. Domini found that some of her clients were offended to be offered stock in weapons manufacturers or tobacco, activities that conflicted with their own values: “You are always supposed to know your customers, where they live, et cetera. I just added to it: ‘Is there something you don’t want me to talk about, or something you have deep commitments to, or something you don’t want to be an investor in?’ Virtually everyone said yes. I was amazed.”

This simple but powerful twist on the staid and conservative investment field became her niche and ultimately blossomed into the growing socially responsible investment field of today.

As a young stockbroker, Domini built her client base in part by teaching adult education classes in the evening. She drew up a course called “Ethical Investing,” which she offered alongside the “ABCs of Investing” class she was teaching. Soon after, she co-authored the groundbreaking 1984 book by the same title (after overcoming her disbelief that no such book already existed!). In subsequent years she would continue this groundbreaking work, as described by Domini Social Investments:

Amy realized that what social investors needed was a benchmark—something akin to traditional investment benchmarks like the Standard & Poor’s 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average—that could be used to determine whether there was a cost or a benefit, in dollars and cents, to invest this way. For example, would an investor who chose not to invest in tobacco companies or major polluters, preferring companies with better environmental and human rights records, perform better or worse than investors who did not consider these factors? She saw this uncertainty as the primary obstacle to the growth of socially responsible investing.

In 1989, she and her partners Peter Kinder and Steve Lydenberg began work on the Domini 400 Social Index, an index of 400 primarily large-cap US corporations, roughly comparable to the S&P 500, selected based on a wide range of social and environmental standards. When it was launched in 1990, it was the first index of its kind. A year later, they launched the Domini Social Equity Fund to provide investors with a fund that tracks the Index.71

Although it comes as no surprise to Domini, these socially responsible investments performed as well as or better than traditional investment portfolios.72

Far from bristling at the regulation of her industry, Domini speaks with a seeming sense of pride at the extent to which the mutual fund industry is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The whole mutual fund industry and its investors benefit from this extensive regulation, even if many of us take it for granted:

The mutual fund industry is a regulated industry. People who complain about regulation don’t even know what regulation is; it’s consumer protection.

—AMY DOMINI

The industry I am in, the mutual fund industry, is a regulated industry. People who complain about regulation don’t even know what regulation is; it’s consumer protection. That’s its purpose. I must do reporting to my board and shareholders on a quarterly basis. My calendar is full of follow-through on mandatory reporting. Still, if you were to say to me, “Which of these regulations would you strip away?” I’d tell you that I am fine with them.

If I were an investor and had an inkling of an understanding of how regulated a mutual fund is compared with other financial management routes, I would be stunned. A financial planner is somewhat regulated; a hedge fund almost totally unregulated—nothing to keep them from being liars, cheaters, thieves, except perhaps laws against fraud or insider trading. The regulatory environment is great consumer protection. In this tough market, where consumers don’t feel protected, [regulation of mutual funds] should give them some comfort.

Domini’s companies, and the whole socially responsible investing field, also benefit indirectly from government-mandated disclosures and regulation of other industries.

I could not have started my business without federally mandated disclosures. For instance, if I am trying to evaluate a company, I look to the company’s own reporting. There is a lot of it. I particularly look at the Form 10K. Corporations must by SEC guidelines release quarterly information, reports, and the annual reports must be audited. The 10K [report required by all publicly traded companies] tells me a lot. But many other sources grow from mandatory reporting.

How many people died in the workplace last year? That is federally mandated disclosure, so that it is available to me in most cases. Are there any environmental liabilities? I look to the 10K, which must by law reveal this (though it is admittedly under-reported). Further, the Toxic Release Inventory [is a] federally mandated data source.

Who are the top officers by pay? In today’s cyber-age it takes about a nanosecond to find out if there are any women or people of color in that top five by pay, and their names are disclosed due to regulation. The board, ditto—federal mandate.

What product safety recalls have occurred? Regulations mean that the information is disclosed, but it is not easy to find. Thankfully, Public Justice, the group that lobbies on behalf of consumers, has a list on their website, which makes it easy. Does the company sell weapons? Weapons procurement is federally disclosed.

Not only do my investors know that the product I offer has robust federal oversight, but I know that the data I rely upon to create that product does as well.

Free-market theory assumes falsely that people have perfect information about the products they are buying, which is necessary for people to make rational choices between competing products. In the real world though, perfect information is almost never available to consumers. Most consumers have little idea about where the products they buy come from or how they were made. The same applies to investors.

The regulatory examples Domini lifts up help make up for that flaw in market theory by gathering valuable information, which Domini uses as the cornerstone of her business model. This is much the same concept used by the USDA in requiring companies to label food products with a list of ingredients and nutritional information. For markets to even come close to functioning as theorized, this kind of transparency is necessary, but it rarely comes without government involvement.

Nikhil Arora: It Takes a Village to Raise a Business

Nikhil Arora is the co-founder and the co-owner of Back to the Roots, an Oakland-based sustainable-products company.80