2

LEAN INTO CHANGE

VISION

Most wildly successful endeavors start with a big Vision, with a capital V. Right? You know, like when Mark Zuckerberg was coding Facebook in his dorm room to pick up girls on campus, and Steve Jobs tried to sell his first customer a bag o’ computer chips and a motherboard that Steve Wozniak had spec’d out. Remember the time when Henry Ford wanted to automate farm equipment because he thought working on his dad’s farm was a drag? That was so cool.

Zuckerberg’s vision wasn’t to invent social networking; Jobs didn’t foresee turning phones into a computing platform; Ford did not invent the automobile.

The story of the solo wolf entrepreneur who, in a flash of brilliance, experiences a “Eureka!” moment that will forever alter the course of history is a myth. It’s simply not true. A truer story is the scientist who makes a discovery by accident, or the engineer who betters existing technology through painstaking experimentation, or the entrepreneur who willingly alters his vision in order to follow market demand.

The successful product rarely matches the entrepreneur’s initial vision, and, more often than not, the end product is hardly recognizable at all. But for whatever reason, the visionary-turned-billionaire narrative makes us feel good.

When corporate consultants and life coaches insist you write a vision statement, they want you to project where you will be in five years. This is the sort of exercise that results in those horribly mundane statements in the “About Us” section of company websites: “industry leader in . . . , the most innovative. . . .”1 Those are the businesses with management teams full of pre-billionaire visionaries.

Irwin Jacobs, founder of telecommunications giant Qualcomm and certified billionaire, purportedly once stood in front of a room full of skeptics (in other words, venture capitalists), held up a brick of a cellular phone, and declared that it would one day be used for credit card transactions. We can only imagine the hilarity that ensued. The vision, however, was really not that extraordinary. It’s not like we couldn’t see it coming. Heck, Star Trek writers predicted the flip phone. (We also never saw Captain Kirk pull out dollar bills to buy anything (heck, there’s no room for a credit card in those pants, let alone a wallet), which leaves either his communicator or his phaser as a means for buying StarBars from the Enterprise’s vending machines. We’re guessing communicator.)

The vision of the solution is not as important as the change you hope to make in the world and your drive to achieve it. Jacobs’s genius was not a vague prediction of what might become of cell phone technology, but rather his relentless pursuit to make global cellular communications possible. Jacobs stopped at nothing; he removed obstacles, ignored detractors, and likely changed the assumptions underpinning his vision numerous times on his way to building Qualcomm into a multibillion-dollar company that pioneered two-way mobile satellite communications.

Remember, it’s not the solution that makes the visionary; it’s the outcome.

Driving Force

Follow your passion is easily the worst advice you could ever give or get.

—Mark Cuban, businessman, investor, and billionaire (ergo: visionary)2

“Follow your passion” is also easily one of the most common pieces of advice given to entrepreneurs. Cuban’s point is that the stuff you’re willing to work hard at is your passion. We prefer a more Zen-like approach, such as: Don’t do what you’re passionate about; be passionate about what you do. But don’t be fooled: If you truly want to effect big change, you’re going to have to do a lot of things you might not really want to do.

What motivates you to work hard? What’s the change you’re seeking? What is the one skill that when push comes to shove you’ll hang your hat on? Try to think of your driving force as a pivot, the thing on which everything else depends.

Take a look at some of these motivating factors—which one most closely aligns with the way you view your idea?

- Market: You want to solve all problems for a specific group of people.

- Problem: You want to solve a particular issue or address a specific passion.

- Product: You have a singular product vision.

- Technology: You have an invention, like a new algorithm or a synthetic polymer, that you wish to turn into a commercial product.

- Channel: You want to pursue a specific approach to the market, such as e-commerce.

The key insight is that your driving force will form the basis of your business model. If you can keep your key motivation in clear focus as you develop your model, many other factors will simply fall into place. Review the driving forces detailed next; which one rings most true for you?

Market-Centric

A company committed to a specific market will develop the products and/or services required to solve one or more problems faced by an identifiable group of people or businesses, or a market segment. A startup begins by solving one need and grows larger as it discovers and addresses additional needs.

For example, you might commit yourself to addressing a specific need of dental hygienists. Or you might want to tap into the new age, new mom segment by creating green diapers, homeopathic teething gel, or a food processor for making baby food—anything to serve that segment.

Once you’ve determined your market segment, you develop your business model from the inside out. In other words, you seek to understand your segment deeply, figure out what problems the members face, and then devise solutions that best suit the customer’s environment.

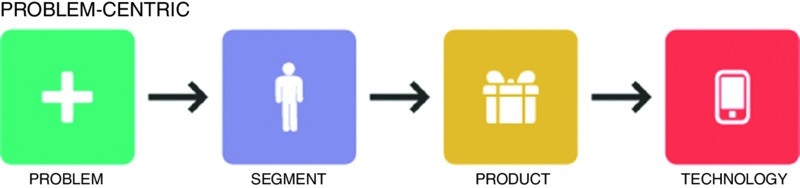

Problem-Centric

Problem-centric business models come from entrepreneurs who have usually experienced a specific problem themselves, or witnessed it firsthand. It’s a natural place to start, since the presumption is that the entrepreneur understands the customer pretty well.

But beware: This can be a trap, on two levels. First, just because you have experienced the problem doesn’t mean that there is an addressable market segment for it. Second, you may be biased toward a solution that the market majority doesn’t want.

A notable difference between the market-centric and problem-centric business models is that the problem-centric model ultimately pursues anyone who has the problem, whereas the market-centric model seeks to solve many problems experienced by one market.

In this scenario, you start with the problem, then define the segment that experiences the problem most acutely, and finally work to define the solution that the market segment is willing to implement. If you truly aim to solve the problem, you are not biased toward a specific solution or technology, but rather you will build the best tool(s) for the job. Scale comes from expanding the solution to solve for multiple market segments.

Product-Centric

If you have a product idea and you will see it built, come hell or high water, it can safely be said that you are product-driven. This is perhaps the most common driving force that we see among entrepreneurs. Oddly enough, it also happens to be the most dangerous. That’s because your product is only as good as the problem it’s solving and its suitability to the segment for which it’s designed.

Products gather dust on shelves, both real and virtual, and businesses spin for years trying to match the value the founders thought they were creating for market segments that may or may not even exist.

If you start with the product, you have essentially chosen the technology that will be implemented to build the product. If you are building a high-tech product and are following the expert advice du jour, for example, then you have chosen to build a mobile product rather than a web-based product. (And while we’re on the topic, good luck finding a business model around your 99-cent app.) Regardless, you had better find that problem your product will solve, and quickly!

Technology-Centric

Technology is a platform or an invention that needs a viable application to succeed. Platforms can be sold separately or launched after an application has established some sort of foothold. Facebook is both an application and a platform. Apple’s iPhone is both, as is Salesforce, 3M, DuPont, and Qualcomm. New chemistry, plant extractions, genetic manipulation, and manufacturing means and materials can all be platforms for new applications.

Entrepreneurs with technology are in search of problems to solve. They can develop products themselves, or they may license their technology or sell access to the platform to others who will attempt to solve specific problems.

Channel-Centric

Channel-driven models seek to innovate around how products are marketed, sold, or distributed. Multilevel marketing (MLM) was a channel innovation that created a pyramid-shaped sales team whereby each member is encouraged to hire new members beneath them and take a cut of their sales revenue. It really doesn’t matter what product you sell, such as cosmetics (Mary Kay) or soap (Amway).

Amazon disrupted book distribution before moving on to selling virtually everything. Some organizations are founded by direct marketers or expert field salespeople, who bring that expertise to a market that hasn’t seen it before. So while their business model might be product- or problem-driven, their driving force is that market-disruptive expertise.

ENTERPRISE NOTE

Big company entrepreneurs should know and understand their companies’ driving force. Improving processes or innovating around the driving force can drive organizational efficiency and competitive advantage.

According to author Steven Spear, the only way for an enterprise to truly thrive is to become a high-velocity organization. A high-velocity organization continuously produces higher-quality products while also continuously improving the processes of producing product. This, Spear argues, is the forgotten lesson of the Toyota Production System: that Toyota figured out “how to do the work in such a way that individuals and groups kept learning how to do that work better.”3

We can take this further: High-velocity organizations not only produce higher-quality products, but they also continuously improve and innovate around their driving force.

VALUES

We once worked with a company that wanted to grow from being a small software company to an enterprise software and hardware company serving a completely different and larger market segment. Its existing technology was sufficient, but the change required a new management team, new products, new marketing, new partnerships, and a new sales model. It required a different culture.

The company was successful, grew fivefold in three years, and was striking fear into the heart of the proverbial 800-pound gorilla in the market. Without warning, the founders then did an about-face. They decided to return to their original business model, even though that market was, by then, dominated by open-source software.

The vision is dependent upon values. You cannot swing for the stars in the comfort of your living room. The big (or small) problem you commit your business to solving describes your vision, while your values describe your “why,” your ethics, and your culture. These elements provide a framework for making business decisions and set both customer and employee expectations in their relationships with the company.

In this example, during the growth quest the founders motivated new and existing employees with a stock-option plan. They insisted that they were looking for a liquidity event (e.g., acquisition), having missed out on the dot-com era. (Red flag, anyone?) In reality, however, they could never pull the trigger. Venture capitalist term sheets and acquisition overtures were turned away.

What the founders had were high salaries and a nice lifestyle business, and perhaps a simultaneous case of founder midlife crisis syndrome (FMCS). There’s nothing wrong with lifestyle companies. Arguably, they are the backbone of the U.S. economy. However, the founders’ vision didn’t mesh with their values, which causes myriad problems both culturally and inevitably with customers.

Values might determine from whom you buy and to whom you sell. Social-cause entrepreneurs commit to serving a particular cause or issue in society at large. Other entrepreneurs may choose not to sell to specific market segments for ethical reasons. In reality, you’re unlikely to ever go public if you’re opposed to taking investment from venture capitalists.

The point of all this is that your vision and values must be aligned.

CULTURE

Arguably, whether you are launching your own startup or creating an internal startup within a bigger business, your team’s culture will go a long way toward dictating your success. Culture doesn’t mean that your offices are in an up-and-coming neighborhood on the wrong side of the tracks in a century-old home retrofitted with a retractable roof, with Nerf guns strewn about, free soda and beer, and weekly Halo network gaming competitions. (Of course, you can have all that if you want and, if you do, we’d certainly appreciate an invite.)

Culture does mean that you create an environment that reinforces your values and aligns the company toward achieving your vision. Lean startup does not have a defined culture, but we can identify a few core philosophies for your consideration.

Your company must be a learning organization. This sounds easy, but it is more difficult to practice. A learning organization puts evidence before rhetoric, experimentation before execution, and customers before business plan. It runs experiments to reduce uncertainty, uses data to resolve conflicts, and interacts with customers to understand them deeply.

DATA

Use data as evidence to resolve conflicts, measure progress, and inform decisions. But not just any data. An organization drowning in data is no better off than one without data. You must focus on the few metrics that measure the biggest growth opportunity for the current business.

At the top of the figure is a high-level objective for increasing revenue growth for a software-as-a-service business. Two choices (there are more) are to increase the number of subscriptions or to reduce churn. Churn (customers canceling subscriptions or not resubscribing) is anathema to the business.

Based on the data that shows 50 percent of customers unsubscribe after one month, it’s decided that the primary objective is to reduce churn. (Acquiring users would be wasteful, since 50 percent of them will leave after one month.)

So what is causing the churn?

There are many possibilities, including:

- Product positioning is wrong: If the product works right but doesn’t match expectations, customers are not satisfied.

- Market segment is wrong: The customers signing up aren’t the right ones; perhaps you’re solving a problem that is not a high priority.

- Product is wrong: It doesn’t actually solve the primary problem or it has user experience (UX) issues.

The key piece of data describes how you expect satisfied users to behave. In other words, what specific usage of the product over some period indicates that the product is working as promised?

Satisfied customers use specific product functionality X over a specific time period Y. You must include an instrument in the product to measure that behavior. How does the behavior differ between those who stay subscribed and those who unsubscribe?

Looking at the right data points to the problem and tracks progress toward solving the problem.

EXPERIMENTATION

A learning organization runs experiments to reduce market and technical risk, test new ideas, and optimize results. The experiments seek to measure real customer behavior—that is, how customers will respond to the product in all stages of the proposed business model, from product ideation through customer acquisition.

At the business idea stage, startups often run landing page experiments that consist of a one-page website that contains their messaging and a call to action. The messaging targets a specific market segment with a promise to solve a specific problem segment members may have. The call to action might be to sign up for an early glimpse of the product. The objective of the experiment is to test whether anyone has an interest in the idea.

Further down the journey, an experiment might be delivering a prototype that demonstrates early functionality and usability. The objective is to determine from the market whether the startup is progressing down the right path.

At the point where new customer acquisition is paramount for growth, the startup might run a test marketing campaign in a new channel. For example, perhaps it posts ads on Craigslist, a popular online classifieds website, in order to test whether a particular segment frequents that site.

CUSTOMER FOCUS

Technology transformations start in the center and ripple out to the edge. The computer revolution started deep in the bowels of the largest organizations in the world. When computers cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, large organizations were the only ones that could see efficiency and productivity gains from the technology.

But as computer power increased exponentially and its cost dropped proportionally, productivity gains rippled through the organization. The desktop and server PC era of the 1990s brought productivity gains to medium-sized businesses and IT departments. The Internet and software-as-a-service era of the early 2000s brought productivity gains to small businesses and to big companies at the department level. Finance, operations, sales, and marketing could now buy their own technology solutions without heavy IT involvement.

The transformation rippled to the edge. Now it’s the individual who sees significant productivity gains with smartphones, software, and apps that solve business and personal issues. This is why customer experience design reigns supreme in product development today and did not five years ago. This also plays into the fact that customers are smarter, have more choices, and have more power.

This is also why organizations big and small must be customer-focused to survive and thrive.

The salesperson who must return to corporate for product information loses the sale. The customer service representative who can’t solve a problem on the spot loses the customer. The company, whether startup or enterprise, that can’t create products with great user experiences and that doesn’t solve real needs will fail. Getting it right is everyone’s responsibility, but it also requires thinking about organizational structure differently.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES

One feature of the industrial age is the assembly line. A common characteristic of mass-production thinking sees workers divided into cells according to their function. Previously, craftspersons assembled the entire product. The assembly line used increased specialization and automation to move products and materials from cell to cell until manufacture was complete.

This approach, coupled with other necessary features like replaceable parts, sped up assembly time, lowered the labor skill necessary, reduced errors, increased worker safety, and dramatically cut costs. Truly, the objective was for labor to be as machine-like as possible—to be as much like capital as the automation that assisted assembly.

This thinking works well when the products are relatively uniform. When Henry Ford produced one car—the Model T—in one color—black—the process was, in fact, quite lean. There was very little waste, other than when cars were overproduced for the demand.

As variation and complexity increased due to new models and optional features, the efficiency of the process was hard to maintain. Machines had to be altered to produce different models, which increased the waste of downtime. Parts that were not interchangeable increased wasteful inventory. The Toyota Production System grew out of the attempt to eliminate the increased waste.

Given today’s market environment, where customers have more knowledge about products than ever before, increased desire for tailored solutions, and a myriad of choices, the complexity from a product-creation point of view is greater than ever.

Not surprisingly, during the industrial age white-collar functions were organized similarly to the assembly line—in other words, by function. Pre-Internet, there were relatively few marketing and sales channels and distribution methods, and communication was broadcast one way, from business to consumer. Therefore, back-office functions—human resources (HR), legal, operations, information technology (IT)—also had fewer complexities in dealing with their internal customers.

Management practices grew out of understanding, replicating, and scaling the processes for manufacturing, marketing, selling, distributing, and supporting the products. Company structure and culture grew out of the need to execute on the plan in known markets.

Until the lean startup, we taught startups to behave like these traditional large enterprises.

But again, things have changed. We’re no longer dominated by industrial age characteristics. We live in a digital world. Large organizations—and the startups that emulate them—struggle to innovate because they’re optimized for execution. They also often struggle to compete, because their organizational structure, culture, and processes were developed in an analog world.

THE TEAM

The prototypical startup seeking to scale (and raise investment capital) is usually founded by two people: a businessperson cofounder and a technical cofounder. While they usually hold the titles CEO and CTO, respectively, they actually wear many hats. They are committed to doing whatever it takes to move the company forward. In today’s customer-centric world, a customer experience designer follows closely behind, as does a marketing and sales expert. (This, of course, isn’t a hard-and-fast rule. Airbnb was started by two designers, followed by a software engineer.)

When thinking of startup teams, whether an independent company or a corporate innovation team, we find it helpful to think in terms of archetypes, rather than titles:

- Visionary: Often the idea originator, or one who has insights into the problem being solved. Often the team leader, the individual who keeps the rest organized and inspired.

- Hacker: The MacGyver of the team. Able to code software prototypes, build websites, string together marketing automation, hack together product demonstrations, and, of course, build actual products.

- Hustler: Fearless. This is the woman who can sell product without a demo and who will cold-call the CEO of a Fortune 100 company without blinking an eye; she can sell sand to San Diegans, ice to Iceland (or should I say Greenland?), and fog to San Franciscans in the summertime.

- Designer: Gets the customer. This person makes things look good and work elegantly. He removes friction from product usability and marketing funnels alike.

Not all the roles are required at the outset, but the skill sets will be necessary in short order. Again, titles don’t really matter. You could have four engineers play the roles.

Again, the old way: Create hierarchical structure; hire product developers; manage feature development; hire marketing and sales; execute big launch plan; track vanity metrics; hope you planned right.

New way: Have flat structure; hire entrepreneurs who can wear multiple hats; focus on learning before execution for the whole business model; iterate until you get it right, based on measuring the right metrics.

BIG, OLD, AND . . . LEAN?

It’s pretty easy for us to sit back and declare that large, successful—even dominant—businesses should act like startups in order to maintain, regain, and protect their success. But we’d be right to do so.

The point isn’t to be critical of large businesses, but there is truth in the observation that the tactics, strategy, and branding that made them big aren’t the same as those that launched them in the first place.

The idea is to put an entrepreneurial culture in place, in order to:

- Move faster in an Internet-fueled, global economy.

- Make decisions based on customer behavior to build more competitive products in existing product lines.

- Find that completely new value proposition that leads to new growth.

It sounds easy, right? Build a startup inside your existing business. Issue the clarion call: Be innovative! Put employees in a startup environment. Hold meetings where employees ideate. Give everyone a bit of autonomy. Go!

Big businesses know they need to innovate. But create a culture of innovation?

The problem is that the term innovation has ceased to have real meaning. It’s a buzzword. To many, disruptive innovation and sustaining innovation have come to mean the same thing. You can’t go a day without hearing how Company X is innovating, is the innovation leader, or is discovering new ways to innovate. It’s innovation by branding. Invention has become the measure, rather than finding a market for an application of the invention. The number of patents held receives more attention than the number of loyal customers.

Universities have a similar issue: lots of research and few applications. Lab-to-market programs teach the 4 Ps (product, place, price, promotion) of marketing and how to write business plans, but not how to discover a market.

Governments that get involved often exacerbate the problem, doling out money to startups consisting of only university researchers occupying space in an incubator. The researchers research, but they don’t create marketable products.

Part of the issue is the old idea that scientists, researchers, and engineers must partner with or turn their inventions over to the business side of the house. We believe, however, that things would be better if the inventors were taught to be entrepreneurs. In order to build things that matter, inventors need to be closer to the market and closer to the problems their technology might solve. Second best is to find domain experts, perhaps other scientists, who are entrepreneurial. The last resort is to use local business experts; this will all but kill the disruptive portion of the innovation.

The business side of the house is used to asking two fundamentally disruption-killing questions:

- What is the return on investment to the organization?

- When will the organization realize the return?

It’s not that business executives are wrong in asking these questions. They are very rational to do so. In large, successful organizations particularly, money is invested in projects that have the highest likelihood of generating significant revenue. Additionally, executives are often compensated for short-term thinking. Bonuses for protecting the business a decade from now are of limited use. In short time horizons, the projects most likely to produce returns are those that address the needs of existing customers.

Existing customers’ needs are well understood, marketing and sales channels are proven, and business processes exist that close the circle between learning what customers need and delivering that value. This describes sustaining innovation to a T. All innovative endeavors will be sucked into the sustaining vortex, because they will be measured against the performance of existing (or recent) products.

Startups and startup-like ventures cannot be held to the same measures, which is not to say they aren’t.

It’s a good way to send a startup into a death spiral, however, wherein execution of best practices is favored over learning and one moves with great efficiency toward failure.

A startup must learn its way, and a large organization that seeks to find new revenue opportunities must learn its way, too. It’s simply not going to cut it when a team of managers is allowed to nix ideas because of their pay grade. Management hierarchy is not structured based on ability to predict the future. Yet that’s what we’re doing, only we use analysis as a euphemism for reading tea leaves.

A large, hugely successful communications company in Southern California made two impressive moves toward improving internal innovation:

First, the company formed (and funded) an organization to create internal startup teams to create products that would, if successful, generate demand for core products.

Second, it adopted lean startup principles with the aim of finding working business models versus formulating a presentation with impressive spreadsheets and pie charts representing crystal ball planning.

Early in the process, we led the teams through a workshop to posit market segment assumptions and problem-solution hypotheses, and to identify core business risks. We established how the teams should get out of the building to learn through customer development, what viability experiments they might run, and what data they should track as they moved through the learning process.

In the end, the teams presented to an internal venture-funding group. The problem was that, like many of their venture capital firm counterparts, the group evaluated the startups based on their own mythological ability to envision the future, rather than the real-world learning presented by the startup teams.

In fact, the whole program was scrapped. It was a repeat of an oft-told story: When the core business needs resources, both capital and human, the internal startups are the first sources to be tapped.

Creating a startup culture is, in our view, the right way to create truly innovative products inside large organizations. There also needs to be a fundamental shift toward long-term thinking. Many U.S. businesses seem to have a cyclical love-hate relationship with long-term thinking. When the economy is doing well, short-term shareholder value is revered, coinciding with stock-option-based executive compensation plans.

To succeed in today’s economy, businesses must be focused on creating real value for customers, not paper value for executives or investment bankers.

The issue remains: How do you do that?

OVER THE HORIZON: A FRAMEWORK

In 2000, McKinsey & Company management consultants Mehrdad Baghai, Stephen Coley, and David White introduced a “three horizons” framework to help break the pattern of large enterprises failing to properly invest in breakthrough innovation.4

- Horizon 1 is the core business, accounting for most revenue. It operates on the sustaining end of the innovation continuum, so the business model is well understood and the company is firing on all cylinders. Public companies report on the performance of Horizon 1 every quarter.

- Horizon 2 represents internal businesses on the rise, including products that have customers, have perhaps achieved product–market fit, and are working on trying to scale big so they can become core to the business—in other words, Horizon 1 units.

- Horizon 3 contains early-stage startups, such as research projects, prototypes, inventions, products in pilot phase, and investments in external young companies. Most of these startups, for a variety of reasons, will fail.

This, it seems to us, is a reasonable way of looking at things. But how these horizons are funded and how they interact with each other are critical to their long-term viability. The three horizons should be seen as a pyramid, with a large number of smaller investments on the bottom, with the hope that a few bubble up to the top. This is the same structure that can be seen within the startup economy.

Geoffrey Moore, author of the marketer’s bible, Crossing the Chasm, sees a problem in the application of horizon planning, whereby Horizon 2 teams are often tossed Horizon 3 projects that are little more than “prototype-stage products,” developed by “lab-centric inventors.” Additionally, Horizon 1 sales and marketing teams are often assigned to push Horizon 2 products that are unviable. Horizon 1 teams have no real incentive to prove the viability of Horizon 2 products; their focus is justifiably on generating revenue from tried-and-true Horizon 1 products.5

The Horizon 2 products—the hope for the future—are evaluated by the same metrics used to evaluate the current Horizon 1 products. But at this stage, they will never measure up. It’s too soon.

“Thus,” Moore concludes, “innovations are better off in bootstrapped startups, because at least there they can get access to the market and suppliers, and their investors will use fairer standards of measurement.”

While we’re not sure the latter prescription is right, the problem is properly identified. For enterprises to innovate, Horizon 3 products cannot be measured in the same way as Horizon 2, or Horizon 2 products like Horizon 1. They need their own metrics.

The way to resolve this is to combine lean startup methodologies with horizon planning with properly defined horizon boundaries. Businesses should use internal startups to prove product ideas and business models before integrating core resources, such as sales and marketing. Furthermore, labs and research centers should be considered pre-startup. In other words, experimentation in the development of technology should be separate and distinct from the experimentation in Horizon 3—these are for developing the right applications of technology for specific market segments.

Product Development

Flow in lean manufacturing means that a product is pulled through the product development process, such that each component is built only when demanded by the next step in the process. In other words, Step B tells Step C, “Now ready for your component.” This process produces the component just in time. This results in less excess inventory and time wastage.

Flow begins with customer demand, not the product manager, the vice president of engineering, or the CEO. In an ideal, web-based product scenario, for example, lean software development would result in features being developed, tested, and released only as the customer has indicated a desire or need for that specific functionality.

When still learning what value is being created or how to improve value, the development is synonymous with experimentation. In other words, instead of building new product functionality that hasn’t been validated, run experiments to validate first.

There’s actually a danger in continuing to develop without concrete demand. It’s very difficult to “feature” your way into product–market fit, but you certainly can “feature” your way out of it. Building features without validation can accidentally destroy the value you’ve already created, by making the product more complex.

So what does product development work on if not new features? Here are a few things that can keep developers busy:

- Pay off technical debt.

- Go learn more about your customers.

- Run viability experiments.

- Search for new innovation.

- Help other company departments improve processes.

The number of lines of code written, or features developed, or bugs knocked out of the bug database doesn’t drive tangible business value separate from the value it provides customers. To be lean, engineering must be able to measure productivity by impact on customers or impact on its internal processes as a value-delivering machine.

Marketing and Sales

In our opinion, marketing can be thought to have one of two approaches:

- Fluffy branding activities, graphics, images, and messaging that appear on TV and radio, in print, and on the web that create buzz, build product awareness, and (hopefully) lead to increased sales.

- Specific campaigns and business activities that move users through a sales funnel, resulting in sustained engagement with the product and increased sales.

The first is thought by most to be a black-box endeavor that requires creative geniuses and pseudo-psychologists to leverage consumer emotion to create need for a product.

The second requires a marketing analytics account to measure the efficacy of the business activities.

A lean startup uses neither approach until it can validate the market segments being pursued, and confirm that they are passionate about the product idea. Startups also determine whether the method of converting prospects to customers is optimized.

A lean startup is not ready to grow big until the product itself is the best marketing tool. And the fact remains that not all marketing activities are right for all products and all market segments.

There is no reason why you can’t apply an iterative learning process to marketing in the same way you might when developing a product. For each phase of your business, your marketing team’s learning plan might look something like this:

- Get out of the building to learn as much as possible about the customers.

- Find out where they are.

- Test messaging to determine what words appeal to the customers.

- Learn how the customers expect to buy and what objections they are likely to voice.

Similarly, employing the wrong salespeople or sales channel has the same deleterious effect as hiring the wrong marketing person. You need to learn how to sell your particular product before executing on a sales plan. The right salesperson establishes which market segments are the best to pursue and how to pursue them. In other words, early sales calls should establish the pattern of selling into a particular segment and what marketing is required to speed up or even automate the process.

Legal and Accounting

If your business isn’t a law firm, then legal matters do not create value for your customers. Typically, these activities are necessary, but not value-adding. (We suppose there are instances in which legal activity does add value to the customer, perhaps through a granting of certain rights, but generally this isn’t the case.)

Legal activities are certainly necessary to protect the business, and without them any business will run the risk of failing. But ideally, legal activities must also enable new value creation, or they become wasteful and harmful to the business’s long-term vision, values, and viability. Legal activities often stifle innovation, because in their effort to protect the existing business, they limit what employees are allowed to do when interacting with customers. For example, we worked with a company that insisted if their employees gathered feature requirements from customers, the customers would own the intellectual property. This is a radical view of intellectual property.

The same can be said for compliance and accounting. Activities that are misaligned with the business’s value creation are wasteful. Businesses with a primary focus of reducing cost, for instance, have little chance of being lean. They might achieve “skinny,” but not lean. The insistence on a fast, measurable return on investment for innovation practices, for instance, kills breakthrough innovation before it can get started.

WORK TO DO

A long time ago, we promised ourselves we would never suggest to someone that they write a vision statement. We will keep that promise. So, instead, you know those fun personality quizzes in airline magazines? We ask you to get in your favorite yoga position—c’mon, admit it, you do yoga—and answer the following questions as honestly as you can. You don’t have to show it to a life coach or anything. There are no incorrect answers.

- Where does your product or idea fall on the innovation spectrum?

- Adds functionality to existing product category.

- Dramatically lowers cost of new product for an existing product category.

- Highly tailors functionality for an underserved market.

- Is an existing product category for a new, large marketplace.

- Is a new product category, in other words an entire new market.

- Is flipping an existing market completely on its head.

- What is your philosophy on taking money to fund the business?

- Bootstrapping, baby!

- Friends, family, and fools.

- Cash, credit cards, coupons.

- Accelerators, angels, a**holes.

- Venture vampires (we’re kidding!).

- What is most important to you?

- There’s a specific market segment I’m committed to and passionate about serving.

- It’s important that everyone have access to my product.

- My technology is game-changing. I just need to find the right application for it.

- My vision is radical, and I will see that it is made real.

- My vision isn’t as important as the fact that I will do whatever it takes to change the world.