12

Strategic Thinking

When we train executives across a wide range of industries and countries, we often ask one of our favorite questions: “If you had a magic wand and could equip managers at your company with any skills, which skill would it be?” We hear one answer in reply more than any other. Based on the title of this chapter, we bet you've already guessed what it is: strategic thinking.

Similarly, a study of 10,000 senior executives found that they chose strategic thinking as the most important driver of business success 97% of the time, and an assessment of 60,000 managers across over 140 countries revealed that a strategic approach was seen as 1,000% more important to perception of effectiveness than any other behavior (Kabacoff 2014).

Execs are confident that if only the leaders in their companies thought more strategically, their companies would be more successful. But when we ask execs to define strategic thinking, they tend to get stumped. Strategic thinking has the dubious distinction of being one of the most in-demand and one of the most difficult-to-describe leadership skills. It is also an important tipping point skill that unlocks better decision-making, problem-solving, planning, project management, influence, communication, and innovation skills. So, it's time to unveil the mystery. Throughout this chapter, we'll help you and your team develop strategic thinking skills faster to make more impact in less time (and become the stuff that executives dream of).

Let's begin Deblurring strategic thinking by learning from contrast. Below is a side-by-side comparison of the average managers versus great managers we studied:

Let's begin Deblurring strategic thinking by learning from contrast. Below is a side-by-side comparison of the average managers versus great managers we studied:

| AVERAGE MANAGER BEHAVIORS | GREAT MANAGER BEHAVIORS |

| Solve today's problems | Also prevent future problems |

| Wait to be told what to do | Propose new ideas |

| Act on their first idea | Compare many different ideas |

| Get their work done | Also improve how work gets done |

| Consider the consequences of their actions | Also consider the unintended consequences |

| React to a problem based on what they see |  Pause to consider what they might not yet see Pause to consider what they might not yet see |

| Make decisions based on their perspective | Invite and integrate multiple perspectives |

| Delegate tasks to their team | Articulate what the goals are and why |

Drawing on these and similar examples we came across in our research, we noticed two commonalities that characterize the strategic thinking superstars:

- They keep the future in mind when taking action in the present.

- They consider the complexities of any situation.

And great managers don't just hone their own strategic thinking skills. They also help their teams think more strategically. In a word, this kind of thinking is hard. It requires an enormous amount of cognitive processing power while your brain attempts to plan for the future by integrating your knowledge of the past and present. And as we've mentioned in past chapters, when people are stressed out and rushing around, this type of thinking is all but impossible. As a result, most teams resort to only occasional bouts of strategic thinking, usually in the form of quarterly or annual planning. But this approach to strategic thinking is far too infrequent in today's world of rapid change, perpetual ambiguity, and interconnected people. Instead, great managers lean on a small set of strategic thinking habits they apply themselves and encourage in their team members in everyday decisions and actions. There are dozens of strategic thinking habits and tools out there, but to help you hone this skill and become an even better manager faster, we'll focus on five cornerstone habits that catalyze strategic thinking the fastest.

1. Gap Analysis

Great managers keep the future in mind when taking action in the present and help their teams do it too. So, the first step on any strategic path is figuring out where you actually want to go in the future, then Deblur that goal by making it measurable. It is tough, if not impossible, to think strategically with blurry goals like “improve,” “reduce,” or the ever-popular “optimize.” So begin with the end in mind. Next, figure out where you are starting, and make that point measurable as well. We call this essential strategic thinking habit doing a gap analysis. Great managers are constantly measuring gaps and instill this gap-tracking habit on their teams.

Great managers keep the future in mind when taking action in the present and help their teams do it too. So, the first step on any strategic path is figuring out where you actually want to go in the future, then Deblur that goal by making it measurable. It is tough, if not impossible, to think strategically with blurry goals like “improve,” “reduce,” or the ever-popular “optimize.” So begin with the end in mind. Next, figure out where you are starting, and make that point measurable as well. We call this essential strategic thinking habit doing a gap analysis. Great managers are constantly measuring gaps and instill this gap-tracking habit on their teams.

| Start | Gap | Goal |

Take a look at the following conversation where Mia misses the opportunity to help Olivia think strategically:

Even though Mia is asking analytical questions about time and budget, it's still impossible to tell whether the bot idea is the most strategic way to reach their goals. Why? Because neither the goal nor the current situation is clear. There is no gap analysis. Skipping this strategic step is akin to hopping on a plane as soon as your friend invites you over to her place. Is the plane the best strategy to get there? It all depends on where your friend lives (the goal), where you live (the current situation), and the gap (the measurable distance between you).

Twenty minutes into a discussion about the website bot, Mia realizes her mistake. She hits her Do-Over Button to try this conversation again, more strategically:

Pausing to do a gap analysis quickly results in more thoughtful and effective solutions. This is one of the primary reasons strategic thinking is such a coveted skill on the executive wish-list. Managers who make it a habit to identify and measure gaps (and help their teams do it too) waste less time on the wrong solutions and come up with ideas that are more likely to succeed.

Pausing to do a gap analysis quickly results in more thoughtful and effective solutions. This is one of the primary reasons strategic thinking is such a coveted skill on the executive wish-list. Managers who make it a habit to identify and measure gaps (and help their teams do it too) waste less time on the wrong solutions and come up with ideas that are more likely to succeed.

In Mia and Olivia's case, if they discover that the average time spent on small accounts is two hours (with a goal of one hour), they will realize that building a bot is an unnecessarily costly solution. In fact, this gap might be so small that they may decide not to prioritize this area of improvement at all. On the other hand, if they find that the team is spending an average of 10 hours per small account, they might recognize that a bot will not be sufficient. To make a strategic decision about the best path to take, they have to start with a gap analysis. As a bonus, making the gap measurable will also let them monitor progress, course-correct when needed, and celebrate success along the way.

What kinds of metrics are most helpful to measure? Great managers tend to measure gaps on two levels: lead indicators and lag indicators. While lag indicators represent your ultimate destination, sometimes these targets are so far in the distance that you need earlier lead indicators to show you if you're on the right track before it's too late to adjust. Here are some examples:

| SAMPLE LEAD INDICATOR (EARLY SIGN) | LAG INDICATOR (ULTIMATE GOAL) |

| Midterm exam grade | Final semester grade |

| Pop quiz grade | Midterm exam grade |

| Number of prospects per quarter | Revenue at the end of the year |

| Post-call client satisfaction score | Number of client referrals |

| Quarterly engagement survey score | Annual employee retention |

The farther away your goal is and the more important it is, the more useful it is to set up multiple gap analysis checkpoints along the way. Whether a goal is someone's lag or a lead indicator depends on the scope of their role. For example, your head of sales might focus on year-end revenue as her primary objective, while your events manager might focus on the number of attendees per month as their primary objective.

To make gap analysis a habit, train your brain to notice when the goal and/or the current state are unclear. Q-step with: “What is the gap between where we are now and where we want to go?” and “How can we make it measurable?” Play back what you hear in reply to help people clarify their thinking.

To make gap analysis a habit, train your brain to notice when the goal and/or the current state are unclear. Q-step with: “What is the gap between where we are now and where we want to go?” and “How can we make it measurable?” Play back what you hear in reply to help people clarify their thinking.

2. Linkup

In a dream world, everyone would begin their work with a gap analysis and have a crystal clear (and measurable) vision of their destination, but the real world tends to get a lot messier. In our research, we saw that it was surprisingly common for people to find themselves in the midst of a “what” without a clear “why.” When great managers recognize they are in this boat, the strategic thinking habit they leverage is to Link up and help others do it too.

In a dream world, everyone would begin their work with a gap analysis and have a crystal clear (and measurable) vision of their destination, but the real world tends to get a lot messier. In our research, we saw that it was surprisingly common for people to find themselves in the midst of a “what” without a clear “why.” When great managers recognize they are in this boat, the strategic thinking habit they leverage is to Link up and help others do it too.

Take a look at the following conversation between Mia and Kofi. See if you notice the vague links that get in their way of their strategic thinking:

Remember the Linkup triangle from Chapter 5? Imagine goals at the top of the triangle and tasks at the bottom. When people rush from one task to the next, it can be easy to lose the link to assume that others are Linking up to the same goals as they are.

Remember the Linkup triangle from Chapter 5? Imagine goals at the top of the triangle and tasks at the bottom. When people rush from one task to the next, it can be easy to lose the link to assume that others are Linking up to the same goals as they are.

Consider the case of Kofi, Mia, and the case studies. If you drew a triangle representing the case study Linkup in Kofi's mind, what goal would you place at the top? In other words, what gap do you think he is hoping to close by creating these case studies? Based on this conversation, your guess is as good as Mia's. If she had a magical thought X-ray machine, or if she just Q-stepped with some Linkup questions, she would be able to see that she and Kofi are thinking about this project very differently:

Consider the case of Kofi, Mia, and the case studies. If you drew a triangle representing the case study Linkup in Kofi's mind, what goal would you place at the top? In other words, what gap do you think he is hoping to close by creating these case studies? Based on this conversation, your guess is as good as Mia's. If she had a magical thought X-ray machine, or if she just Q-stepped with some Linkup questions, she would be able to see that she and Kofi are thinking about this project very differently:

| KOFI'S IMPLICIT LINKUP | MIA'S IMPLICIT LINKUP | ||||

|

3. To improve sales close rate |  |

3. To increase sense of meaning | ||

| 2. To build client credibility | 2. To show the team's impact | ||||

| 1. Create case studies | 1. Create case studies | ||||

Maybe Olivia didn't delegate the assignment well. Maybe Kofi didn't Q-step or Play back to check for alignment. Whatever the case, he is now driving toward a very different goal than the original intention. Pausing to make the implicit Linkup explicit would have made this miscommunication clear.

Maybe Olivia didn't delegate the assignment well. Maybe Kofi didn't Q-step or Play back to check for alignment. Whatever the case, he is now driving toward a very different goal than the original intention. Pausing to make the implicit Linkup explicit would have made this miscommunication clear.

Aside from ensuring alignment, the Linkup habit helps you pressure-test people's thinking by asking, “Is this the best way to achieve this goal?” For example, perhaps a more efficient way to give the team a sense of meaning is to invite them to attend client meetings. A better way to improve the sales close rate might be to offer free consultations. Pausing to Linkup might seem like it slows things down, but it prevents us from going fast in the wrong direction. Besides, even a very short Linkup Pause is enough to rapidly kick-start strategic thinking. Take a look at Mia's quick Linkup Do-Over with Kofi:

Sometimes, Linking up helps people realize they are juggling multiple goals. For example, in Kofi's case, it could be tempting to look for a solution that increases meaning and improves the close rate. While it is occasionally possible to kill two birds with one stone (or our much preferred expression: feed two birds with one scone), a single solution that achieves multiple results well is rare. A case study that is polished enough to send to clients might also increase the team's sense of meaning but do so at an unnecessarily high cost. Several professionally produced case studies might improve the close rate, but they won't provide ongoing visibility into the team's impact. The result? Two birds that ate one scone and are both still hungry and cranky. Instead, great managers clarify which goal is the highest priority and create a different Linkup map for each one. If you find that rare gem of a solution that achieves multiple goals, go for it. If not, select the best solution to achieve your most important goal.

Sometimes, Linking up helps people realize they are juggling multiple goals. For example, in Kofi's case, it could be tempting to look for a solution that increases meaning and improves the close rate. While it is occasionally possible to kill two birds with one stone (or our much preferred expression: feed two birds with one scone), a single solution that achieves multiple results well is rare. A case study that is polished enough to send to clients might also increase the team's sense of meaning but do so at an unnecessarily high cost. Several professionally produced case studies might improve the close rate, but they won't provide ongoing visibility into the team's impact. The result? Two birds that ate one scone and are both still hungry and cranky. Instead, great managers clarify which goal is the highest priority and create a different Linkup map for each one. If you find that rare gem of a solution that achieves multiple goals, go for it. If not, select the best solution to achieve your most important goal.

How much time and effort should you spend considering different paths toward your goal? It all depends on the importance and urgency of the goal and the risks involved in acting too quickly or too slowly. In general, the higher the stakes, the more important it is to Pause and Linkup.

How much time and effort should you spend considering different paths toward your goal? It all depends on the importance and urgency of the goal and the risks involved in acting too quickly or too slowly. In general, the higher the stakes, the more important it is to Pause and Linkup.

To make Linking up a habit, frequently Q-step with: “What does this link up to?” and “Is this the best way to achieve this goal?” When delegating work or assigning responsibilities, Linkup to the goal and Deblur it.

To make Linking up a habit, frequently Q-step with: “What does this link up to?” and “Is this the best way to achieve this goal?” When delegating work or assigning responsibilities, Linkup to the goal and Deblur it.

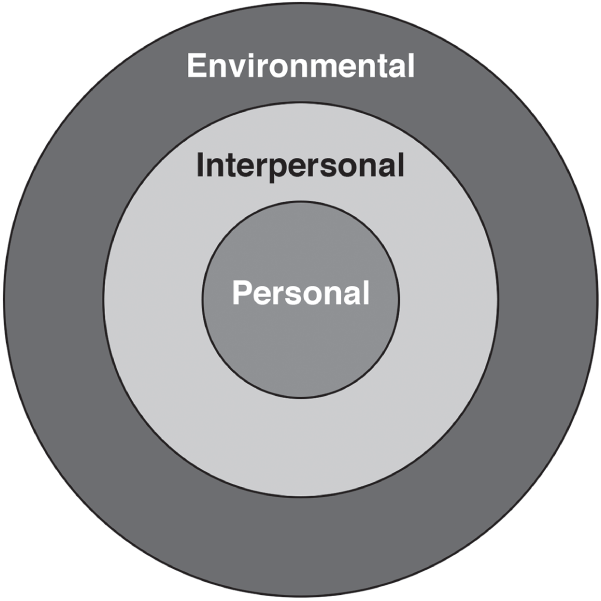

3. The 3 Lenses Model

As we mentioned at the start of this chapter, strategic thinkers incorporate the future into their present decisions, but there is more to it than that. They also consider the complexities of any situation. And few situations are more complex than those involving interpersonal problems. Without strong strategic thinking skills, it's easy to miss the many factors involved in interpersonal challenges by simply blaming the people involved. The result? People waste time, effort, and emotions attempting to solve the wrong problems or getting bogged down in destructive conflict. By some estimates, unproductive conflict costs companies an average of $359 billion per year (Hayes 2008). By contrast, great managers resolve interpersonal problems faster by looking at them through multiple lenses. We call this strategic thinking habit the 3 Lenses Model. To adopt this habit, look at any person-related problem through three lenses, and help your team members do it too:

Source: LifeLabs Learning.

- Lens #1: Personal. Ask: “How are they contributing to the situation?” For example, does this person lack the skill or will necessary to achieve this goal?

- Lens #2: Interpersonal. Ask: “How am I contributing to the situation?” For example, have I failed to set clear expectations or model and reinforce the desired behavior?

- Lens #3: Organizational. Ask: “How is our team and/or company contributing to the situation?” For example, are there resource constraints or problematic org-wide norms?

Without a quick 3 Lenses analysis, you can easily miss the complexities of a situation and overlook creative solutions. As a case in point, take a look at another exchange between Mia with Olivia later in the week:

Why do you think Olivia is butting heads with Jeff despite her best efforts to improve their relationship? Based on this conversation, it's hard to say, and Mia's suggestion is premature. She's missing out on an opportunity to help Olivia Pause and think strategically about the different factors that may be contributing to Jeff's behavior. Keeping the 3 Lenses Model in mind, Mia goes back in time with the help of her Do-Over Button to help Olivia diagnose the situation more strategically:

Why do you think Olivia is butting heads with Jeff despite her best efforts to improve their relationship? Based on this conversation, it's hard to say, and Mia's suggestion is premature. She's missing out on an opportunity to help Olivia Pause and think strategically about the different factors that may be contributing to Jeff's behavior. Keeping the 3 Lenses Model in mind, Mia goes back in time with the help of her Do-Over Button to help Olivia diagnose the situation more strategically:

To get in the habit of using the 3 Lenses Model, as soon as you detect interpersonal tension, Pause and Q-step with: “What are the different factors that might be contributing to this situation?” Be sure to Play back what you hear to help folks clarify their thoughts.

To get in the habit of using the 3 Lenses Model, as soon as you detect interpersonal tension, Pause and Q-step with: “What are the different factors that might be contributing to this situation?” Be sure to Play back what you hear to help folks clarify their thoughts.

4. UC Check

While average managers do tend to think through the consequences of their actions and help their team do so too, great managers go even further to ensure everyone is thinking strategically. They develop a habit we like to call doing an UC Check (pronounced Uck!): they check for unintended consequences.

Before we explain how UC Checks work, let's first consider the story of the Hawaiian mongoose. In 1883, Hawaiian sugar cane plantation owners had a problem. Rats were destroying their crops. In an attempt to find an organic solution, they imported 72 mongooses to control the rat population, then shipped baby mongooses across a variety of Hawaiian islands. The mongooses did eat the rats, but they also ate birds and insects that pollinated the crops. By now, the mongooses and their offspring have cost Hawaiian farmers tens of millions of dollars in damages (Gamayo 2016). How did the little mongoose become such a big problem? Everyone involved focused on the desirable consequences (fewer rats) and nobody did an UC Check to anticipate the unintended (and undesirable) consequences.

Why is it so easy to forget those pesky UCs? Human brains easily fall victim to the confirmation bias – a tendency to search for evidence supporting one's perspective while ignoring contradictory evidence. When people are excited about a solution, it's difficult for them to see any information that disconfirms their beliefs. Great managers know this and nudge themselves and others to anticipate what might go wrong.

The goal of the UC Check is not to avoid taking action but to shine a light on unseen consequences so you can take even more thoughtful and strategic action. Once you identify risks and possible negative impacts, you can consider how you might mitigate these consequences. In some cases, the result might be choosing a different solution (please, no more mongooses!). In other cases, the UC Check will guide you to do more research or tweak your plan – for example, involving more people or running a pilot before a full launch.

As we mentioned in Chapter 7, another great tool to anticipate unintended consequences is the pre-mortem. Unlike a post-mortem, which helps people Extract lessons after a problem occurs, a pre-mortem starts with the premise that something will go wrong, before it actually does. To run a pre-mortem, invite impacted stakeholders to imagine that a project or decision was a failure, then ask: “What caused things to go wrong?” and “What can we do today to prevent these problems in the future?” Research shows that the practice of “prospective hindsight” increases ability to identify unintended consequences by 30% (Mitchell, Russo, and Pennington 1989).

As we mentioned in Chapter 7, another great tool to anticipate unintended consequences is the pre-mortem. Unlike a post-mortem, which helps people Extract lessons after a problem occurs, a pre-mortem starts with the premise that something will go wrong, before it actually does. To run a pre-mortem, invite impacted stakeholders to imagine that a project or decision was a failure, then ask: “What caused things to go wrong?” and “What can we do today to prevent these problems in the future?” Research shows that the practice of “prospective hindsight” increases ability to identify unintended consequences by 30% (Mitchell, Russo, and Pennington 1989).

To get in the habit of doing UC Checks, ask yourself and others the following questions before making a decision or introducing a change:

- “What might be the unintended consequences?”

- “What might the risks be?”

- “Who might be negatively impacted?”

- “How might we mitigate the UC?”

5. Inclusive Planning

Of all the strategic errors we've discussed so far, research shows that one is worse than all the rest: not including the right people at the right times (Neilson, Martin, and Powers 2008). While on the surface this seems like an easy mistake to fix, the solution tends to get complicated. How can you ensure that you aren't forgetting to include someone? What if you include too many people? At what point in a project or decision should each person get involved? The good news is that one strategic habit simplifies this complexity and helps you and your team make good decisions faster. We call it inclusive planning.

The first part of practicing inclusive planning is to break up a project or decision into distinct phases. In most cases, the project phases will include the following:

| Inclusive Planning Grid | ||||

| Phase 1 Define goal |

Phase 2 Analyze problem |

Phase 3 Explore solutions |

Phase 4 Pick solution |

Phase 5 Execute |

Phase 1 is all about doing a gap analysis by Deblurring your end point and start point and making them measurable.

Phase 1 is all about doing a gap analysis by Deblurring your end point and start point and making them measurable.- Phase 2 is an opportunity to diagnose the current problem or situation using the 3 Lenses Model.

- Phase 3 is the point at which you'll want to generate many ideas to close the gap (we'll share idea generating pro-tips in the next chapter).

- Phase 4 is when you narrow your options and select one solution (stay tuned for tips on how to do this well in the next chapter). This is also a good time to do an UC Check.

- Phase 5 is the point at which you actually execute on the plan.

All along the way, Linkup to ensure the goal stays clear to everyone involved.

All along the way, Linkup to ensure the goal stays clear to everyone involved.

Notice that each phase of the process creates an opportunity to Pause and invite your strategic thinking habits to the party. When you break down work into these phases, it also allows you to Deblur who should be involved at each point. Looking back on the many times Luca has felt excluded since Mia has been manager, inclusive planning could have been the ideal solution.

Notice that each phase of the process creates an opportunity to Pause and invite your strategic thinking habits to the party. When you break down work into these phases, it also allows you to Deblur who should be involved at each point. Looking back on the many times Luca has felt excluded since Mia has been manager, inclusive planning could have been the ideal solution.

To determine who you should involve at each phase and develop an inclusive planning habit, ask yourself and others these questions:

- “Who will be impacted by this?”

- “Who will have to execute on the plan?”

- “Who might be a vocal advocate or detractor?”

- “Who might have relevant insider scoop or expertise?”

- “Whose perspective might we be overlooking?”

Once you decide who should be involved at each phase, make your plan visible. In this way, you'll help your stakeholders understand how, when, and why they will be asked to contribute. If someone believes they should be included in a different phase, you'll have the opportunity to Pause, Extract the learning, explain your reasoning, and course-correct, if needed.

Once you decide who should be involved at each phase, make your plan visible. In this way, you'll help your stakeholders understand how, when, and why they will be asked to contribute. If someone believes they should be included in a different phase, you'll have the opportunity to Pause, Extract the learning, explain your reasoning, and course-correct, if needed.

***

In summary: Strategic thinking entails considering the future and the complexities of any situation. A handful of strategic thinking habits helps managers and teams make better decisions: Gap analysis, Linkup, 3 Lenses Model, UC Check, and Inclusive Planning.

In summary: Strategic thinking entails considering the future and the complexities of any situation. A handful of strategic thinking habits helps managers and teams make better decisions: Gap analysis, Linkup, 3 Lenses Model, UC Check, and Inclusive Planning.

MY LAB REPORT MY LAB REPORT |

Today's Date: |

| My takeaways: | |

| I regularly think strategically: | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (strongly disagree)(strongly agree) |

| Experiment idea bank: |

|

| One small experiment I'll try to increase my score by 1 point: | |

| Post-experiment Learning Extractions: |

![]() Bonus: Want to take your manager skills to the next level? Check out the bonus Inclusion Stations at leaderlab.lifelabslearning.com.

Bonus: Want to take your manager skills to the next level? Check out the bonus Inclusion Stations at leaderlab.lifelabslearning.com.