What will they ask me?

THIS CHAPTER LOOKS AT:

- Your best strategy for anticipating questions

- Getting into the interviewer’s mindset

- Predicting the key items on the employer shopping list

- Emphasising organisational fit, attitude and working style

Every time I sit with a client and try to predict interview questions, it becomes clearer that there is little new under the sun. While in theory an interviewer could ask you anything at all, a large proportion of interview questions are entirely predictable. So why do we worry so much about what will come up, or the prospect of ‘awkward’ or ‘difficult’ questions? It could be nervous avoidance, but could also be an admission that we haven’t really put enough effort into preparation. You might feel there are thousands of possible questions (a great excuse for not preparing for any of them), ignoring the fact that there are clearly some questions more likely and more important. The difference between success and failure may in fact rest on just a few questions.

SEEING THE MAIN AGENDA

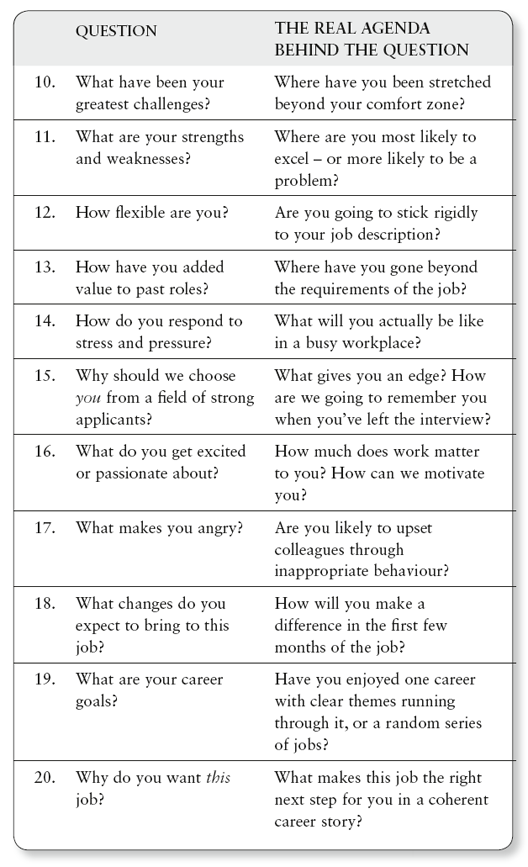

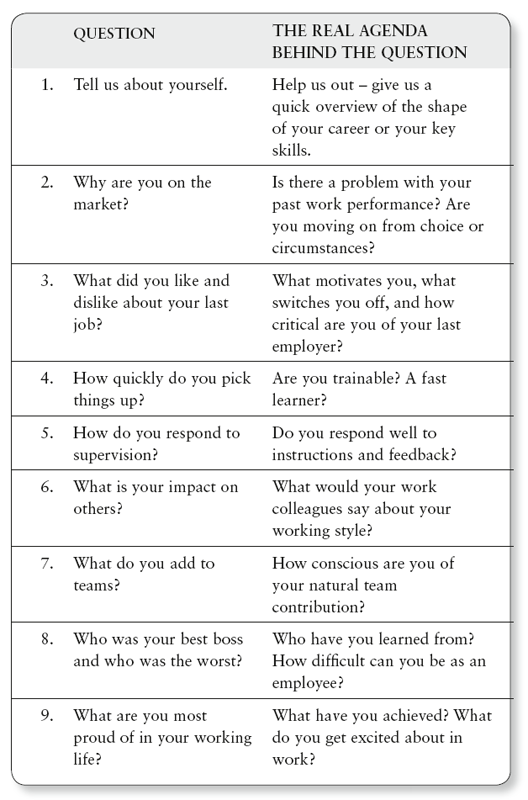

One of the most frequent reasons candidates get lost in the interview process is that they haven’t grasped the basics – the questions that are most likely to come up in any interview:

Twenty of the most frequent interview questions (and what’s really under discussion)

INSIDE THE MIND OF THE INTERVIEWER

To predict the questions most likely to come up you need to get into the mind of the interviewer. Interviewers have two big problems: there are always more questions than time, and it’s unclear which questions will be effective. And they have one objective: to get the right result, which means retrieval of evidence credible enough to tick the items on the employer checklist. Some of that list is visible to you and some of it you have to intelligently guess at, but a checklist definitely exists. So instead of worrying about what might come up, focus hard on what probably will come up.

Some questions will inevitably arise from the claims made in your CV or application form, cover letter, and possibly also in competency statements (see Chapter 15 for more on competency-based interviews). These questions are entirely predictable, but be prepared for your evidence to be put under the microscope, particularly those areas which suggest you may not be perfect for the job.

Recruitment consultant Pauline Godley writes ‘Some interviewers focus on finding reasons to decline people so the short list is strong, as opposed to getting the best from candidates. A cynical view, I know, but having received feedback on hundreds of interviews over the years there does seem to be a slant on the negative. There are some very astute, commercially focused employers who really do look for the best in candidates, but they are few and far between.’

From this it’s clear that there may well be a focus on those relatively small number of areas where you don’t match the job and therefore can be discounted. An important strategy for all of the topic areas listed below is to ask yourself ‘What parts of my CV is the interviewer worrying or doubtful about?’

ATTITUDE

Your attitude is not just probed in questions, but revealed in everything you do – responding to instructions, the clothes you choose for the interview, the working style revealed by your stories. Naturally you wouldn’t be reading this book if you weren’t committed to showing real interest in the job – or would you? Employers repeatedly complain that candidates convey apathy rather than enthusiasm – they want a job, not necessarily this job.

It’s best not to make direct statements about your attitude; for example, saying you are a ‘self-starter’ or ‘a winner’. This might work on The Apprentice, but interviewers in fact feel more secure if they discover personal traits for themselves. Saying ‘I am passionate about detail’ may prompt an inexperienced interviewer to nod approvingly and make a note. You have only made a claim, not proved it – even if the interviewer approves, he or she has nothing to remember, which means that your evidence hasn’t been absorbed. To another interviewer this kind of statement is so free of content it sounds like unconvincing boasting, and an invitation to begin aggressive probing.

Show them, don’t tell them. Telling a story where you clearly gave attention to important details works much better and sticks in the interviewer’s memory. Most new graduates this year are telling employers that they are highly motivated, self-starters, team players and will go the extra mile. Don’t waste your breath making empty claims – let your attitude come out in memorable narratives, so that the interviewer comes to a conclusion without the point being over-signalled.

‘FIT’

Organisational fit may seem like a matter of chemistry, which some people believe you have no control over (see Chapter 17 on personality issues), but in fact you do have a great deal of control over what you communicate, beginning with the first impression you create, and working through examples you provide of working with others. Judgements around organisational fit are made very quickly, largely in terms of behaviours that you can think about in advance:

- Be courteous and friendly to everyone you meet on the day.

- Don’t dominate the conversation, as this is taken as a clear indication of how you will operate in a team situation. Listen to questions carefully without interrupting.

- Tune in to the flow of the interview so you get a sense of when it is appropriate for you to stop talking.

- Be flexible around the requirements of the interview day, particularly if they are changed at the last minute.

- Give appropriate evidence of co-operative and consultative working (matched, if necessary, by times where the buck stopped with you).

WORKING STYLE

An employer wants not only to know what you can do, but what the impact of your work is on others. Yes, you can manage a budget, but how many toes do you tread on in order to get at the information you need? How do you lead others, or respond to authority? If you need to cut costs, can you do so without causing a staff walkout? Bearing in mind that the main reason people leave a job is their relationship with their line manager, employers know that working relationships matter.

Think very hard about this issue if the person who is interviewing you is someone who you will have to work alongside. What is it about you that might be worrying them – perhaps you’re too assertive, too bright, or they think you will be telling them how to do their job?

UNDERPINNING KNOWLEDGE

Knowledge is something that interviewers feel is rather easier to get at, largely because a great deal of it is certificated in qualifications or training. Nevertheless, you should think of each of these simply as headings. There are tens of thousands of courses and qualifications out there, yet candidates generally assume that interviewers know about all of them. Explain the things that excited you as part of your learning. What can you do now that you couldn’t do before?

Learn to talk about training which was informal and not certificated, perhaps because you learned on the job. Be clear about specialist knowledge – think of times when colleagues asked your advice or sought you out as an expert.

CONSTRAINTS

Constraints are sometimes simple issues like the earliest date you can start. Other issues are more complex, and these matter if the decision maker sees them as potential deal-breakers, for example the question of a long commute to work or the need for relocation.

Pay levels can be a constraint, too, particularly if the employer feels you can be hired for a low salary (focus on what you will deliver, not what you will cost) or you are too expensive (show how you will be good value). Wherever possible talk about salary and other terms and conditions once you have been offered the job.

Do address constraints head-on if you believe they might be worrying the decision maker. So, for example, if you are half way through a part-time degree and this hasn’t come up, find the chance to talk about how you are good at juggling study and work commitments. If issues like this are never discussed they can end up as reasons to turn you down.

SKILL RANGE AND LEVEL

With constraints resolved in the interviewer’s mind, you can now roll your sleeves up and get through your skills. Remember to combine claims with evidence – identify your skills and provide evidence of where you have used them.

A professional interview will establish the skills you are comfortable using and your skill level. A weak interview might accept your answer ‘I’m pretty good at using Excel’, but this kind of answer does you no favours – terms like ‘beginner’, ‘proficient’ or ‘pretty good’ provide no meaningful data about ability and just lead to interviewer uncertainty.

Give examples at the top end of your skill range – times when you have done something difficult. Potential is attractive, but experience carries more weight: where exactly have you used this skill? What problems did you overcome? What were the actual results you achieved? How much support or supervision did you need?

Don’t underestimate your skills, as people often do. Learn to talk enthusiastically about the skills you are good at and find satisfying to use (see the section on ‘motivated skills’ at the end of this chapter for a tool that will help you identify them). Talking about the skills you use outside work often gives a more rounded picture.

MOTIVATION

A related area is around the things that drive you. You may be asked directly about the things in your job you find give you the biggest ‘buzz’. Think in advance about what these are – when you visualise work on a Sunday night, what activities and situations do you actively look forward to? Often these are around people, challenge, learning or solving problems, but everyone is different, and our motivators change as we grow older. Think about what works for you, and then match them to the role on offer; there’s no point saying that you’re motivated by innovation and change if the job involves neither.

LEARNING CURVE

When an interviewer is thinking about motivation, often the real question is about your learning curve. Every job is a learning curve, and the first part of that curve is about novelty and excitement.

How trainable are you, and how long will it take you to learn a new role and new ways of working? If there are skills you don’t currently have, how quickly are you going to absorb them? Here it’s usually enough to tell good stories about where you have been thrown in the deep end in the past and done well.

What happens when the curve levels out for you – what keeps you motivated in the long term? Good questions will focus on how you respond to the routine aspects of the job, and how long you are likely to stay in the same role. But if you don’t get asked questions that allow you to give a full picture of your abilities here, then work it into another answer when you get the chance.

ACHIEVEMENTS

Your motivation is often revealed in your achievements, which are the best way of convincing an employer that you have done, and can do, the things you claim. Your CV should be full of them (make them measurable, interesting and punchy) but always have a few extra achievement stories up your sleeve ready for a probing interview.

Remember that achievement stories really are ‘stories’ – there should be an engagement factor (see Chapter 13). If your stories are remembered, your abilities are, too.

KILLER QUESTIONS

Yes, there may be some oddball questions or really tough ones. Again, the tougher ones can be predicted. You may well be asked where you want to be in five years’ time – your answer will reflect how clear you are about your career story. You will almost certainly be asked about weaknesses as well as strengths. Don’t allow yourself to be put on the spot by something you can see coming a mile off (but see Chapter 17 on oddball questions).

YOUR DISTINGUISHING FACTOR

If your skills, knowledge and attitude fit, an interviewer may still be looking for something else. The last question is often unstated, but it is essentially ‘as we have a number of candidates who can do the job, why should we choose you?’

Prepare for that one – what is the special mix that makes you different? Maybe it will be simply that you have more enthusiasm, more interest, better questions, better evidence. What an employer is often thinking is ‘How will I remember you after you have left this room?’, and the answer is not just about information, but a combination of the same four factors that get salespeople remembered:

- immediate positive impact;

- matching your solution to the employer’s problem;

- offering credible responses to probing questions;

- finding common ground and shared experiences (personal ‘hooks’ like this are very powerful).

Behind every inspired performance is the hard work of good preparation, readying you for the big questions to come.

MOTIVATED SKILLS

It’s virtually impossible to get a picture of all your skills on your own. However, I have developed a tool, the JLA Skill Cards, to identify your top 10 motivated skills, i.e. the things you are good at and enjoy performing. A full range of exercises are provided, enabling you to communicate your skills in terms of career highlights and achievements. The cards come with a full set of instructions plus exercises to help you identify skill gaps, your learning agenda, and ways of communicating your skills through achievement stories.

See www.johnleescareers.com/skillsCards.asp for details.