2 The Benefits and Limits of the Business Unit

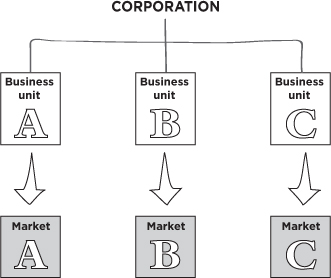

BUSINESS UNITS date back to the 1930s, when General Motors took the leadership position in the car market from Ford.1 Ford had become extremely good at process innovation during that decade—streamlining its operations to be the lowest-cost automobile producer—but General Motors was better at reading the consumer of the time. While Ford was busy working to keep costs down, GM was capturing new market segments for which price was not the main purchasing criterion. More than one car market existed, and GM restructured its organization to serve multiple markets. Contrary to the traditional functional organization, GM was divided into business units—each focused on a particular market segment, each with its own brand, each run as if it were an independent company (figure 2.1). This structure proved to be much faster than the traditional organization at capturing the demands of customers and translating them into new designs.

The widespread use of divisional structures and business units speaks to their success.2 Razor focused on execution in a particular market, they beat any alternative management solution developed thus far. In the absence of industry revolutions, execution and the ability to manage incremental innovation decide winners and losers. Focusing on being more efficient, more attentive to shifts in customer needs, and more creative in addressing and fulfilling customer needs pays off.

Figure 2.1. The business unit structure

However, while it is hard to argue against smooth, efficient, and low-cost operations, the better a company becomes at executing its existing business model, the less attention it generally pays to the development of breakthrough innovations. Ford’s early focus on continually improving cost savings is another illustration of the innovation paradox—the way relentless pursuit of incremental innovation often crowds out the possibility of breakthrough innovation. The temptation is for managers to favor ideas that reinforce the existing strategy rather than consider those that challenge it.

Responding to shifts in industries, some incumbents misguidedly double their current efforts, essentially doing more of what they are already doing. For example, before refrigerators existed, ice was used to keep things cold. The ice-harvesting industry constantly improved each of the various stages of the value chain: growing ice in lakes, harvesting ice, transporting ice, and storing ice. When the refrigerator was invented—a breakthrough innovation at the time—it seriously challenged this well-established industry. At first, the refrigerator was dismissed as an inferior technology—one that was much more expensive, and noisy. As consumers became receptive to the refrigerator and its performance proved to be a real threat, the ice-harvesting industry essentially put its blinders on. Ice providers did not shift their strategy to include the new technology that was eroding their business. Instead, they kept improving the efficiency of their existing processes. The most significant improvement in ice-harvesting technology actually happened when the refrigerator had already achieved dominance—long after the development would have made any difference.3

But the innovation paradox is tricky. Just because someone has a great idea does not necessarily mean that they will execute it best. Fast seconds—often the winners in new markets—do not come up with the original breakthrough idea, but they win because of their ability to copy, improve, and execute better. While breakthrough innovation can disrupt and create new markets, it can’t do much of anything without execution.

Business units have proven to be very effective at stimulating incremental innovation. Their focus on specific market segments—products or geographies, technologies, and competitors—enables easier target setting, performance measurement, and course correction. In environments that are changing faster than ever before, however, new technologies can quickly alter the rules of the game. Industry boundaries become increasingly fluid, leading to the emergence of new competitors from environments that previously didn’t exist, or that were traditionally off these business units’ radar screen. Unless an organization makes a concerted effort to look beyond today’s markets, technologies, and competitors, its focus on execution and incremental innovation can become a handicap when adapting to rapid and profound change.

Business units are razor focused on execution, and incremental innovation is integral to staying ahead of competitors. Yet incremental innovation often crowds out breakthrough innovation in this organizational design.

THE BENEFITS OF BUSINESS UNITS

Business units are generally organized using a structure based on functions. Core functions reside at the business unit level, while support functions are often centralized to gain from economies of scale and scope. This structure is designed to deliver value through flawless execution and a good dose of incremental innovation. Like an Olympic swimmer who trains and trains to cut a hundredth of a second off her time, business units compete to get that extra point of market share or reduce costs by a percentage point. Table 2.1 lists some of the advantages of utilizing business units based on a functional structure.

Business Units Excel at Execution and Guiding Continuous Progress

Successful, established companies are superb at execution. Sure, many of them started with a breakthrough idea, but an idea in itself does not make a successful business over the long term. For example, Inditex, the company behind Zara and other clothing brands, came up with a radical approach to commercializing fashion, but its continued success depends on its ability to execute on and constantly improve upon its business model. Walmart’s original idea to establish large stores in rural Midwestern cities gave the company its start, but keeping “everyday low prices” requires constant effort to improve operations.4

Table 2.1. advantages of the business unit structure

Business units, based on functional structures, are hard to beat as long as the industry structure remains stable. Yet their strength is diluted when facing structural changes in the industry.

Most markets tend to remain stable for long periods. Their structure varies slightly and slowly, and they seldom experience radical changes to their technologies or their business models. During these stretches of stability, perfecting execution is the best way to get the most value out of an existing business model. Like that same swimmer training for the Olympics, tracking progress also requires constant measurement. While capital markets focus on quarterly earnings, monitoring can be an ongoing activity within business units. The business unit itself can measure its financial performance monthly or weekly; it can keep tabs on nonfinancial performance measures daily, or even hourly. Since execution leaves little room for efforts that do not pay off within a reasonably short amount of time, quickly knowing what’s working and what isn’t allows business units to respond effectively.

Business Units Encourage Incremental Innovations through Targeted Resource Allocation

Another benefit of business units is their ability to encourage incremental innovations that advance existing strategies through targeted resource allocation. The traditional approach to incremental innovation is driven from top management in a few ways, one of them being resource allocation. These decisions are then primarily evaluated in terms of financial returns. Of course, other criteria come into play, but it’s hard to argue against financial returns. Investments with higher expected returns will have a higher priority.

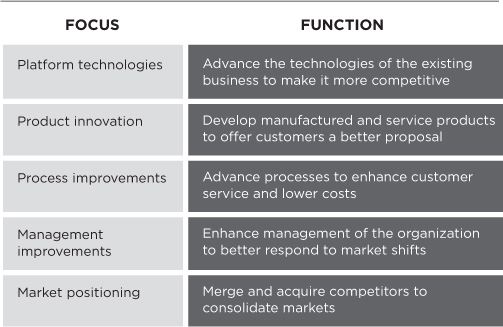

Table 2.2. resource allocation for top-down incremental innovation

The way top management allocates investments heavily affects how incremental innovation will play out. For example, a company that invests heavily in supply-chain software will open up more options to improve the management of its supply chain than will a company that invests strictly in improving the technology of its products. That said, management can allocate resources to a number of places as part of strategies for incremental innovation, and top management investment decisions—whether to invest more in a certain business unit than another—send important messages about current priorities (table 2.2).

Investing in platform technologies. Today’s R&D investments focus on technologies that have a clear application in existing businesses. For instance, making a detergent with stronger cleaning power or a lower environmental impact requires a large investment. Few companies direct a significant portion of their R&D to breakthroughs, as Bell Labs did with the transistor in the 1950s. While some companies are able to transform happy accidents into new markets, the R&D labs’ central purpose is to advance the mid- to long-term technology needs of existing businesses.

Investing in product innovation. Incremental innovation investments go into product development in the form of designs for new versions of existing products. Succeeding at product innovation requires intense customer intimacy, and well-managed business units are skilled at getting to know their customers.

Investing in process improvements. Innovation budgets also include investments in process improvements to increase efficiency and quality, reduce costs, and enhance customer satisfaction. Process innovation often is acquired through adopting new hardware and software from external suppliers.

Investing in management improvements. Investments to improve the management of the organization—making it more efficient and better at meeting customer needs—take the form of software, training, and consulting. All management processes now utilize software; training transfers knowledge in the organization so that employees can improve execution; and consulting allows for innovation to be acquired from external suppliers and adapted to the needs of the company.

The way top management allocates investments heavily affects how incremental innovation will play out. Continuous progress comes from top management’s planning process and how its investment decisions advance existing strategies.

Investing to improve market positioning. Investments to improve market positioning are often associated with acquisitions that consolidate the industry and give the buyer a stronger bargaining position, or that offer an entry point to a new geography or market. The success and failure of acquisitions hinge on the ability to execute on the integration of the acquisition.

Business Units Create Value with Demanding Cultures while Balancing Risk and Motivation

Investments to reinforce incremental innovation are often sizeable, and deciding where to allocate resources is never a sure thing. Even if the uncertainty is low, the financial impact of investments that end up failing can be dangerously high. For instance, initial tests of a high-speed train track discovered that the ballast of the track was hitting the bottom of the train when train speeds were high. The unexpected effect ultimately limited the speed of what was supposed to be a high-speed train. The solution came only after a significant investment in R&D to redesign the ties of the track to make them aerodynamic.

One way to manage this kind of risk is to stage investments. For instance, various companies now manage new product development using a stage-gate process (figure 2.2). Development goes through stages, and the end of each stage has a gate at which top management evaluates the project. At that point, management can either give the go-ahead to move the project to the next stage, make changes, or cancel the project altogether. Different companies have different numbers of stages, but all stages serve the same purpose: to periodically review investments with the option to cancel so that an organization can cut losses quickly on investments that aren’t working.

figure 2.2. The stage-gate process

Another way for top management to generate continuous improvement is by planning and monitoring progress. Planning yields a set of targets that employees throughout the organization have to meet. Ideally, these targets are challenging but achievable. Henkel CEO Kasper Rorsted, for example, relied heavily on making people more accountable in transforming the company. Accountability was enforced through a culture that emphasized the customer; a transparent evaluation system to identify top and bottom performers; and a balanced incentive system with individual, team, and company incentives. The drive for performance resulted in people throughout the company identifying new opportunities for growth and efficiency.

Pushing for performance can lead people to be more creative, but that pressure needs to come with risk management systems and a balanced culture. Without them, creativity can undermine, rather than support, value creation. For example, Microsoft performance has been average over the last decade—the company’s stock price has barely appreciated. Analysts speculating on reasons for this have cited a corporate strategy that follows trends instead of creating new ones, and an evaluation system based on forced ranking—or stack ranking—which encourages people to worry about their own ranking rather than to collaborate to create value.5

To avoid the risk of people using their creativity to invent dangerous short cuts, strong codes of conduct are important. These boundary systems or ethical guidelines set limits on what behaviors are acceptable and what kind of activities fall within (and outside of) the approved strategy. Making shared values explicit shapes a healthy culture that supports the creation of economic and social value.6 Such systems channel organizational energy in the right direction and help deter people from using their creativity to undermine the system.

Demanding targets lead people to be creative in finding incremental innovation opportunities as long as the associated risks are managed.

Giving people challenging yet achievable targets forces them to be creative to improve how they work. But this creativity will remain at the individual level unless mechanisms are put in place to disseminate it. Incremental innovation isn’t always about demanding targets—sometimes it’s about facilitating and leveraging the creativity that lies dormant within an organization and its networks.

Business units can Manage Emergent Improvements

With the right systems in place, it is possible to stimulate and capture incremental innovation throughout the company and its networks. These management systems channel the ingenuity of employees, customers, and almost anybody who is in some way related to the company. When business units successfully manage bottom-up incremental innovation, they integrate creativity from all these sources into a formal innovation process.

Software companies such as Amazon and Google often use A/B experiments, a systematic approach to selecting among competing ideas. By offering various designs of the same web page at the same time to different visitors, companies can monitor which design works best. Marketing companies employ similar approaches for choosing between marketing campaign alternatives. Another example of a business that encourages and manages emergent improvements successfully is Keyence, a Japanese designer and builder of automation devices for factories. The company has devised a process whereby employees spend long periods of time at the factories of its customers, interacting with and observing them. These visits have led to multiple ideas about new products and new ways to serve customers.7

Even utilizing a simple tool like a suggestion box requires managing the innovation cycle. Simply hanging up a box (or posting a web page) will not get creativity flowing; the process needs to entice and encourage people to share their ideas. Various tools—from tournaments to exploration trips and interest groups—are intended to stimulate inventiveness, expose people to new experiences, and offer economic and social rewards. The ideas that emerge need to be evaluated, selected from, and ultimately implemented. For company-wide efforts, the management of hundreds or thousands of ideas and their evaluation, selection, and implementation may require a large number of people.

Incremental innovations often lead to small performance improvements, but occasionally they also may mean very large revenues or savings for the organization. In such instances, it can be tempting to commit to further incremental innovation—where business units, after all, excel. But what incremental innovation has working in its favor can almost just as easily work against it.

THE LIMITS OF BUSINESS UNITS

Over the past hundred years, business units have been the preferred organizational structure largely because they deliver value. However, while they are in many cases the best way to execute a strategy, their core advantage becomes their core weakness when industries go through revolutions. Their focus on execution and incremental innovation can crowd out any real opportunity for developing breakthrough innovation.

Business units are built on the assumption that the market will evolve slowly and predictably. Thus, their search for ideas is often local; they frequently look for innovation in technologies and business models close to where they currently are. When industries go through large structural changes, a business unit’s intuitive response is often to do what they know best—only more of it, and faster—and to try to protect an old industry structure rather than adapt to the new one. As former Procter and Gamble CEO A. G. Lafley said, “First-time chief executives rarely have much experience with weighting the balance toward a long-term future. Typically, they’ve been accountable for results only a few months out. Their careers have not depended on bets placed a decade or more into the future.”8

The company that originally came up with the concept of business units, General Motors, illustrates some of their pros and cons. For decades GM dominated the car industry by playing on the competitive advantage that business units’ focus provided. As long as the industry remained within a set of fairly narrow parameters, GM kept winning. But changes in the market—customers demanding new concepts, energy prices skyrocketing, and foreign competitors such as Toyota offering better cost and quality management innovations—challenged GM’s leadership position. The inertia of business units to reinforce past winning strategies led to the company’s bailout by the US government in 2009. Table 2.3 lists the major limits of the business unit structure.

Table 2.3. Limits of the business unit structure

Defensive Attitudes within Business Units Reinforce Existing Business Models

Few companies can quickly adapt to large shifts in their industries. Kodak, the eternal leader in the photography film industry, is another winner-turned-loser because of business units’ characteristics. The company dominated film for decades, beating every competitor who entered the industry. But the coming of digital photography ultimately forced Kodak into bankruptcy. As with Nokia and the smart phone, the irony of the Kodak case is that the company was the first to go into digital photography. It created the original digital camera and predicted its eventual success, but the inertia of Kodak’s past winning strategy, reinforced by defensive attitudes within its business units, did not allow this breakthrough innovation to grow. The company kept getting better and better at executing for what had become an increasingly small market.

Business units assume Steady and Predictable Industry evolution

The assumption that industries will move steadily has been true most of the time and in most markets. For example, the structure of the energy industry has remained stable, the rules of the game basically have not altered for decades, and the main players—Shell and Exxon Mobil—have stayed at the top throughout. Why should a particular renewable source of energy upset this solid structure? Alternately, education today looks much as it did two hundred years ago, and some aspects have not changed for thousands of years. Why should we expect something like e-learning to challenge these traditions? From the vantage point of business units—which assume steady and predictable industry evolution—we shouldn’t. However, the assumption of slow movement within industries sometimes fails, and when it does, the business unit structure may find itself unable to respond.

Existing Power Structures within Business units can Be Sticky

Radical changes in an industry require a new configuration of knowledge. The information that was once at the core of competitive advantage becomes peripheral in the new competitive landscape, while knowledge that before was subordinate now becomes core. Still, several forces fight to maintain the status quo, even if mounting evidence indicates that current strategies are no longer valid. One such force is a company’s power structure. The internal power struggle in a particular newspaper in Europe is a case in point. Product market forces were obvious to all top managers: the paper had fired more than 20 percent of the workforce over eighteen months as former readers of print moved to find their news online. The dynamics of the market were clearly changing rapidly, but the paper team—the team that had held the power within the organization for decades—was not ready to let the Internet business dominate. Perceiving the Internet business as a side business since its inception, the paper team decided to rename itself the “Internet team” in a weak attempt to hold onto power.

Business units measure Short-Term Results

Another inherent limitation of the business unit design for breakthrough innovation is its short-term orientation. Performance is measured quarterly in the stock markets, and more often internally, and innovation can only be argued for if it delivers on its promise sooner rather than later. Rewards, promotion opportunities, and reputation are tied to short-term results, and managers respond to these incentives by focusing on delivering in the next quarter. A manager from Boeing described this frustration: “I often wonder, if society existed [in the past] as it does today with the media, politicians, and lawyers and managers focused on not missing earnings by two cents per quarter, whether we would have made the advances of the past.”9

Business units Demand Predictable and Stable results

Business units are averse to uncertainty. Investors value predictable and stable results and tend to shy away from volatile assets. Radical ideas are often too uncertain to support stable financial performance, even after using portfolio techniques to limit idiosyncratic risk. Thus, business units often favor innovations low on uncertainty, whose financial returns are predictable. This tendency for business units to favor the safe makes the decisions of the Kodaks and Nokias of the world—to focus on past successes rather than new technologies—seem logical. However, results are predictable and stable only up to a point. When radical market changes occur, the risk aversion of business units can be their downfall.

Execution Routines within Business Units Reject Radical Ideas

The management systems built for execution—budgets, processes, quality control, and sales pipelines—are designed to reduce variation and enhance efficiency. These systems see variation as a problem rather than an opportunity. Deviations from the expected are quickly addressed to bring the process back in line with the plan. The quality of these routines determines the quality of execution in stable times. Even if the industry structure is going through radical changes, execution routines still frequently reinforce the patterns that had been successful in the past—almost as if organizational antibodies rejected change to maintain stability in the body of the organization.10

Business units are best designed for predictable industries. Often their response to radical changes in industry structure is to reinforce previously successful strategies—strategies that are becoming obsolete.

BUSINESS UNITS, FUNCTIONAL STRUCTURE, AND BREAKTHROUGH INNOVATION

There is one notable exception to business units’ typical inability to create and respond to structural changes: visionary CEOs who go for strategic bets. A strong CEO with a vision to disrupt an industry and the muscle of an execution-oriented company to pursue her radical concept can bring about breakthrough change.

A business unit structure shaped to execute the strategy designed by top managers can deliver on breakthrough innovation if it comes from the top. The best example is Steve Jobs’s turnaround of Apple in the late 1990s. The iPod, iTunes, the iPhone, the iPad, and the App Store were all part of the vision of Jobs and a tight group around him. Not only did these developments disrupt current markets and create new ones, they dominated them—in large part because of the quality of the vision and the organization’s ability to execute on it. But Steve Jobs at Apple isn’t the sole noteworthy case. Lou Gestner at IBM and Sergio Marchionne at Fiat are also leaders whose concepts saved their respective companies. The leader has to be inspiring, trustworthy, and tough enough to break the forces within the company that will react negatively to her vision. But if she gets people to rally behind her, she has an organization that can upset an industry.

Getting the organization to fall in line behind a visionary leader is easier when the company’s performance is deteriorating. Apple had just gone through three CEOs before Jobs came back, and the company was viewed as a relic from the early years of the computer industry. Gestner took over when the consensus was that IBM was going to disappear. Marchionne got to the helm when Fiat was losing market share in most of its markets and its cars were being described as dull. In such circumstances, employees and investors agree that change is needed, and they are much more likely to be ready and willing to support the new leader.

No matter how you look at it, the visionary leader is ultimately betting the company on her vision of the future; she succeeds if she has the right vision and her breakthrough innovation creates a new market or upsets an existing one. But breakthrough innovation is a risky business, and more often than not, the turnaround fails to happen. Visionary leaders can have the wrong vision or fail to implement it successfully.

Few leaders have more winning visions than losing ones. Those who do are business geniuses who more often than not get the future right and build it. Geniuses play a pivotal role in all aspects of life; they are outliers who shape the way we live. Many significant advances in society are the outcomes of these visionaries, and they exist in every walk of life—music, architecture, painting, chemistry, biology, and political science. Of course, to implement their vision, most of these people needed both the support of teams and the ability to manage them. Business is no exception.

Business units have a number of advantages, and being able to execute on the vision of a leader is ranked high among them. Unfortunately, most managers are not geniuses, so betting the future of an organization on the vision of a CEO is a risky proposition. In fact, breakthrough innovation is itself quite risky, but it is necessary for the continued growth and survival of an organization. For insight into how risk-averse organizations can learn to thrive in uncertain environments and not-yet markets, we look to those who live and thrive in ambiguity: startups.

Few leaders have successful visions of the future more often than unsuccessful ones. The ones who do bring about breakthrough innovation by leveraging the ability of business units to execute on their vision of the future.

QUESTIONS FOR ACTION

• How well does my organization execute compared to similar organizations around the world?

• How is the strategic planning and budgeting process designed? How does it motivate progress?

• How is progress measured in my organization?

• How motivated are the people in my organization?

• Are the management design and culture of my organization demanding yet maintaining a healthy attitude?

• How does my organization manage the various sources of risk?

• How does my organization incorporate emergent improvements?

• What is the role of continuous progress in my organization?

SOURCES OF RADICAL CHANGES IN THE INDUSTRY

• What experiments around the world could challenge the existing industry structure?

• How is my organization tracking these potential sources of radical change?

• What are the main assumptions that drive my organization?

• How hard would it be to shift the mental model of my organization if the industry goes through a radical change?

DRIVING STRUCTURAL CHANGE

• How does my organization support a discovery mentality to lead breakthrough changes?

• How does my organization combine focus on execution and an open approach to experimental breakthrough solutions?

• How does my organization balance the weaknesses of a business unit structure?

• What changes to the existing design of my organization could balance the strengths and limitations of a business unit structure?