2. Collaboration, Cooperation, and Reciprocity

2.1. Human Nature and Human Science

Some of you may remember the events of January 28, 1986, and the image of the space shuttle Challenger streaking skyward only to disappear in a cloud of white exhaust, errant boosters, and falling debris. In the coming months and years, much of the blame for the disaster was placed on the decision-making process at NASA and the subcontractor Morton Thiokol.1 It was well known that the O-rings tended to become rigid and unseal at low temperatures, even temperatures found in Florida. The launch-time temperature was 30 degrees Fahrenheit, well below the safe launch threshold. The O-ring failure may have led directly to the disintegration of the shuttle, but the actual cause of the disaster was a decision-making process that ignored the facts, did not involve and listen to those with critical information, and had a “culture” that rewarded launch over safety.

Roger Boisjoly was an engineer with Morton Thiokol who knew there was a high probability of a catastrophic failure of the O-rings. Six months prior to the disaster, he sent a memo to his superiors warning them of potential problems. On the day before the disaster, Boisjoly and four others engineers attempted to warn their superiors about the dangerously low temperatures and the probability of an O-ring failure. They were disregarded by Morton Thiokol’s general manager, who told them to “Take off your engineering hats and put on your management hats.”2

Mr. Boisjoly reported his firm’s failings and paid a heavy price for his whistleblowing and subsequent lawsuits against Thiokol and NASA. One colleague at Thiokol threatened to drop off his children at Boisjoly’s doorstep if they lost their jobs.3 NASA was also dismissive. The only NASA official to show Boisjoly any support at the time was astronaut Sally Ride, who served on the commission examining the tragedy. However, Boisjoly recovered and went on to speak at more than 300 universities about data and ethical decision making. NASA also made sweeping changes and became a model of analytics, collaboration, and participative decision making. Launch decisions were made based on the best available data and only after input from everyone involved, including the astronauts flying the mission.4

The story of the Challenger disaster makes a poignant and critical point: The best data and the most sophisticated algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) technology on the planet are not going to make a bit of difference if the facts are ignored, and, just as critically, if the culture (that is, the incentives and decision-making structures) rewards and promotes non-value-maximizing behaviors. How do we structure our companies and decisions to reduce the possibility of the wrong decision and increase the probability of making the right ones? How do we develop organizations where people and teams with critical information are heard, listened to, encouraged, and rewarded for speaking up? What technologies can assist with making the organization more collaborative and with getting the right information to decision makers?

Not all decisions may be so impactful as to lead to the loss of life; however, the wrong decisions will almost certainly lead to the loss of optimal organizational performance.

2.1.1. Reciprocity and Fairness

When I first moved from the Midwest to the East Coast, I had a “bias” that everyone in the region was going to be in a big rush and generally rude and aggressive. Soon after arriving, though, one of the first things I noticed was that people would hold doors open for me, sometimes for what I considered to be an inordinately long period of time. I decided that perhaps these East Coast types were not all that rude and rushed, and I happily joined the ranks of door holders. Recently, I was sharing my East Coast door-holding observations with a friend and learned that she had found the same thing. However, she also noticed that some were gaming the door-holding goodwill and waiting for people to get the door for them. She suggested that when I find myself at a glass door, I see whether the person on the other side has stopped and is waiting for me to get the door for them. I live in an apartment complex with glass doors, so this was easy to do. I started observing fellow residents’ and guests’ door-holding habits. Whereas most people went out of their way to get the door, a few would wait (a long time) for people to get the door for them. This was not expectant mothers, the elderly, or even people carrying a ton of stuff. Instead, they were generally completely able bodied and otherwise-unencumbered folks who were generally younger and less encumbered than I. So, when I approached the door and could see one of the door-holding gamers waiting for me to get the door for them, I would stop, smile, and wait to see who blinked. Because they realized someone was on to them, they would quickly get the door.

Before you start thinking I am being rather petty, turns out I am far from the only one who is concerned with fairness, reciprocity, and equality. As it happens, these characteristics are fundamental to who we are. As a matter of fact, it is hypothesized that reciprocity and cooperation may in part drive our very evolution. Harvard biologist and mathematician Michael Nowak stated the following in a seminal article:

Thus, we might add “natural cooperation” as a third fundamental principle of evolution beside mutation and natural selection.5

The article evaluates five different reasons for the existence of cooperation: kin selection, direct reciprocity, indirect reciprocity, networked reciprocity, and group selection. It appears that even at an evolutionary level cooperation may promote greater “fitness” when compared to a competitive model.

2.1.2. Selfish, Greedy, Lazy, and Dishonest

A long-held assumption within economics is that humans are fundamentally a greedy, lazy, and selfish species prone to lying and cheating.6 You might think that I am overstating the case for dramatic effect, but I assure you that I am not. Much of this evolved from Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” and the notion that each of us seeking our own self-interest will ultimately lead to better outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith might not have been promoting the kind of self-centered “greed is good” that his notion evolved into, but over the years it is difficult to argue that it has not led to a rather one-sided view of human nature, at least within economics.

This negative underlying assumption about our nature has had a big effect on the way in which incentive contracts and the employment relationship has been theorized and ultimately implemented within organizations. Managers sometimes go to extreme lengths to monitor workers because otherwise, of course, they goof off all day. The surveillance in place at some organizations can be downright Orwellian. Even if your every move is not being monitored, in many places, the “command and control” work environment is alive and well. In addition, tournament-based incentive contracts are largely if not exclusively focused on individual accomplishments, often providing no incentive to share potentially useful information, and sometimes even providing an incentive to sabotage the work of others. So, what on earth are the 3Ms and the Googles of this world doing when they allow their employees one day per week to work on whatever they want? Clearly, from the perspective of economic self-interest, giving employees a day off each week to pursue their own interests is the same as giving them, well, the day off. Of course, if this policy did not exist at 3M and Google, we might not have scotch tape and Gmail.

2.1.3. Human Nature 2.0

One of the most prolific and influential economists working today is Ernst Fehr at the University of Zurich. He and his collaborators have had the same impact undoing the fundamental belief that we are all primarily greedy and selfish that Kahneman and his co-authors had on unraveling the notion of rationality. Fehr and others have closely examined notions of altruism, reciprocity, cooperation, and fairness and have found that we are actually a very unselfish and helpful species.7 Who knew, right? He and others have gone further and applied these findings to the way in which the employment contract is structured. Taken in light of their work, the 3M and Google model does not appear to be so absurd. As a matter of fact, if you hire the right people and have the right incentives and culture in place, you may be able to give employees two days off a week to work on their own projects. (Imagine what they might come up with.)

We are actually quite good at self-regulation. The political scientist Elinor Ostrom, another recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, has shot holes in the long-held notion of “the tragedy of the commons.” This concept suggests that when left to our own devices, we will exploit a common resource until it is devastated. However, clearly it is hardly in a fisherman’s self-interest to decimate the fish population or ranchers to use up all the water. Turns out the use of the commons in not so tragic; exhausting all common assets just does not always happen. An example is water rights in Arizona and fishing rights in Massachusetts. Both have been successfully self-regulated, with the resource remaining intact.

Again, all you have to do is look around. Humans clearly do not always make decisions rationally, and humans are also empathetic, altruistic, concerned about being treated fairly, and also want to see others treated fairly. Need further proof? Look no further than April 15, 2013, the day of the Boston Marathon bombings. One of the first things you will notice if you look at photographs or videos of the attack is that many, many people are running toward the site of the bomb detonations. This included many first responders; however, it also included many normal citizens. There is nothing rational or self-interested about running toward the site of bomb blasts. The rational response by a rational self-interested agent would be to turn and run like hell in the opposite direction. Two bombs had just detonated, dramatically increasing the probability of there being more. Nonetheless, a few moments after the explosions, so many people were assisting it was difficult to even see the victims.

2.1.4. Fierce Cooperation

When people hear the word cooperation, they sometimes envision people sitting around in a circle sharing, actively listening, and generally affirming what others are saying. While all of these conditions may well be a part of the cooperative process, cooperation and cooperative behaviors are not always affirming. Take, for example, the notion of reciprocity: I will look out for you, but you also need to look out for me; if you don’t, I may call you on it.

As with many of the topics that really engage me, I came to the notion of reciprocity and mutual monitoring largely through the back door. Maya Kroumova and I were interested in the impact firm size would have on the effectiveness of broadly distributed stock options.8 Agency theory would strongly predict that the smaller the firm the more likely they would be to have an impact on firm performance. The idea being that in a small firm—say 30, 100, 500 employees—it is much more reasonable to expect that employees would think that their actions would ultimately impact the share price, consequently providing more motivation for them to work longer and harder. What we found was that firm size did not matter at all. Small, medium, even large firms all benefited from the use of broadly distributed stock options. We were surprised by this finding and tested and retested the data only to find the same thing. At the time, the finding did not make a tremendous amount of sense to us, so we suggested more research be conducted to evaluate what actual mechanisms were at work. We promptly sent the paper out to a number of journals, and it was promptly rejected by all of them (though you can find it at SSRN.com).

We continued to work and rework the paper trying to figure out what was going on, and then one day noticed that a number of behavioral economics were referencing the paper in their work and using it to support the notion of mutual monitoring.9 It started to make sense; at the organizational level, one of the reasons that reciprocity works is because, mixed with the right incentives, employees have an incentive to keep an eye on one another. If your rewards depend on the contribution of others (as they do for everyone holding shares in the same company), you are more likely to call someone on it if he or she is not being productive. What we found was that both small and large firms did better. If this was the mechanism at work, size would not matter; as a matter of fact, the bigger the firm would be more likely to benefit from shared rewards like broad-based stock options, because having everyone keeping an eye on everyone else was much more efficient than other forms of monitoring.

The evidence is becoming more clear on this; mutual monitoring and reciprocity is more efficient than hiring many managers to monitor the workforce, or putting in place expensive surveillance equipment. This is not to suggest that developing a culture of collaboration is cost free, just that the alternative is often more costly.

2.1.5. Collaboration

Those of you who saw the movie A Beautiful Mind10 may remember the scene where Russell Crowe (who played John Nash, the 1994 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics) imagines a scene meant to depict an aspect of game theory. In the scene, five young men in a bar spot five women, one of whom is exceptionally attractive; the other four are merely very attractive. The five make a beeline for the exceptionally attractive woman and all vie for her affections. The attractive woman is perturbed by this and annoyed that her friends are being ignored, so she ignores the men. Her friends are equally angry at being slighted, so when the young men turn their attention to the friends, they rebuke their advances. The five men decide their best strategy is to work together. Instead of going after the exceptionally attractive woman, they head directly to the friends. Everyone hits it off, and so by working together, they are each individually able to improve their utility.

The scene is meant to depict a core notion of game theory, which states that sometimes our individual utility is enhanced when we collude or work together. This is contrary to the standard neoclassical view that essentially states we should all pursue our own self-interest and from this the most efficient outcomes will result. Clearly, the notion of collusion here is used in a good sense: working together, sharing information that facilities better decision making. An increasing body of work outside of economics also supports this notion of cooperation over individual utility maximization. There are examples of this in the natural sciences, as well. The biologist E. O. Wilson found that when it comes to cooperative behaviors, groups that learned to cooperate among themselves were much more likely to survive and prosper.11 There is substantial and growing evidence again, across many different disciplines and functions, that the more we can work together, the better the performance outcomes. Academia is one place that has benefited greatly from the free collaboration and the free flow of ideas and information. The open source software movement, Wikipedia, and all the other wikis are all excellent examples of collective collaboration. Many of us benefit from this kind of collaboration, and many of us also contribute to these efforts.

In addition, substantial and interesting work is being done on the wisdom of crowds and collective intelligence; we are simply smarter together than alone. Thomas Malone, the founding director of MIT Center for Collective Intelligence, believes that organizations need to fundamentally change because all the new technologies have resulted in a change not in the production technology, but rather in the coordination technology.12 These coordination technologies include the technologies that we will be discussing that promote better decision making.

2.1.6. Hard Wired to Share What We Know

It’s official now: It is highly unlikely that a Planet of the Apes scenario will ever exist here on Earth. Turns out that an undervalued aspect of what sets humans apart from all other species is our tendency to share our knowledge. Our willingness, even desire, to share what we know is referred to by anthropologists as ratcheting.13 And this is no small thing; it might be one of the most important qualities that allowed humans to advance and thrive. Our tendency to share what we know may have provided us with an insurmountable advantage when it comes to competing with all other species. Universities excel as places where information is shared broadly, but many organizations are not good at sharing information (although there are notable exceptions).

Knowledge management has been around for some time and has a mixed record of success.14 Much of this mixed success relates to actually getting people to utilize the systems in place, and it appears that incentives are the problem (and organizations being locked into these systems). A sophisticated enterprise content or knowledge management system will go to waste if the right incentives and organization does not support it. The organization consists of a number of elements, including content management software systems and a culture of collaboration and information sharing.15 There has to be an incentive to share information and an incentive to collaborate. The system itself is just one small piece of the puzzle.

This notion of reciprocity or reciprocal altruism is also well understood within cultural anthropology literature. We are much more likely to be generous with those who are generous with us, and the same applies on the organizational level. The topic of knowledge management is a broad one, and our focus here is on how collaborative decision making and how you can use new and developing technologies to assist in decision making. One of the fastest-growing segments of knowledge management is the use of collaborative software systems to assist with decision making. An ever-growing body of literature across many different disciplines provides support for the efficiencies of collaboration.16

2.1.7. Collective Intelligence

Some of the better known examples of the utilization of collective intelligence include Wikipedia and InnoCentive. InnoCentive is a web-based service that outsources companies’ research problems, inviting solutions from the web community. Good ideas are rewarded with cash prizes. Of course, this is one of the reasons democracy works as well as it does. It is impossible for any one person to see the whole picture, but collectively we often get it right (maybe not right away, but eventually).

Individually, we are prone to make decisions that are susceptible to all sorts of individual biases and environmental factors. However, when we gather information from a variety of information sources, we are much more likely to make good decisions. Unfortunately, a number of historical and environmental factors paint democracy in the workplace as somehow being subversive.17 Many strongly support democracy at a national level but not at the organizational level. This is an unfortunate fact, because like our desire to share what we know, getting involved in our organizations should be encouraged (as should expressing what we think).

2.1.8. Asymmetric or Private Information

The core reason that employee involvement and cooperation and collaboration are so critical relates to the notion of asymmetric or private information. There was a time in my own career when many organizations put in place employee participation programs, but primarily as window dressing. As you can guess, they were not especially effective. However, if done right, employee participation programs can serve two equally critical functions. They can serve to better engage employees, and they can serve to get the best possible information to those who are making decisions.

The term used in the economic literature to describe this type of information is asymmetric information or private information, and the fact of its existence is why organizations should go to tremendous lengths to ensure that their employees are engaged, motivated, have a strong incentive to share information, and (probably most important) that they do not leave. Once you have found someone who is an especially good fit with your organization, you want to go to great lengths to ensure that he or she stays. The information they have at their disposal, and whether they decide to share and act on this information, has the potential to tremendously increase the probability of organizational success.

Asymmetric information simply means that only I know what I know. Only the individual knows how hard he or she can work, for example, or whether he or she has any good ideas about how to improve the production process. If they are in direct contact with the customer, they also have significant information about how customers like to be treated and about customer preferences. If the employees are in direct contact with the products being built, they also have access to tremendously valuable information about the production process and the quality of the products. If they are responsible for new product development, they certainly have a great amount of information about great new products. Not leveraging this information is like organizations leaving money on the table, but many organizations do just that.

2.1.9. Game Theory 101

This section discusses the classic example of the prisoners’ dilemma, often used to explain game theory. You can see from the following example that it is the self-interest of both prisoners to hope the other prisoner confesses. However, it is not in either prisoner’s self-interest to confess. It is unlikely that either prisoner will convince the other to confess. So in this case, the best possible outcome is one of working together or cooperating. There will be a cost, but it will not be as high as if they both choose to go it alone, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Collaboration and shared decision making work because by setting shared rewards people eventually figure out that it is in their self-interest to work together. One aspect of game theory that human capital management (HCM) has direct bearing on is employee turnover. The greater the employee turnover, the less likely that a cooperative culture will emerge. This argues that there should be a premium placed on ensuring that key contributors stay with the organization.

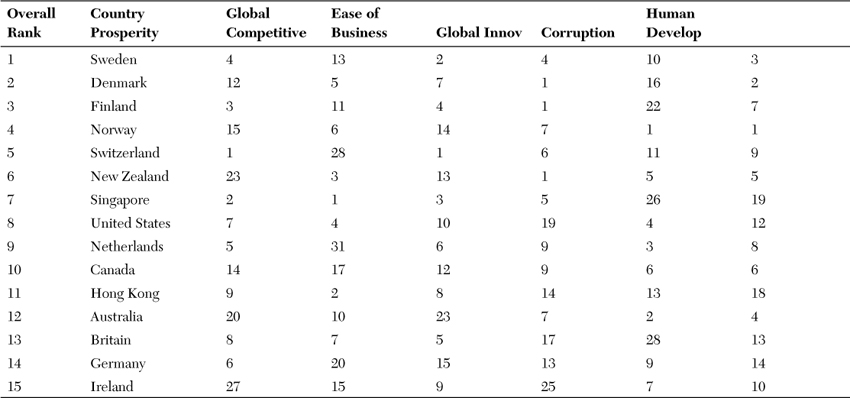

2.2. The Power of Collaboration: The Scandinavian Model

Each year, a number of business publications list the best countries or cities to do business. The cover of a recent issue of The Economist magazine announced “The next supermodel” while showing a picture of a Viking (a Viking with his nose turned up). The subtitle under the picture of the skeptical-looking Viking was “Why the world should look at the Nordic countries.” This edition of The Economist includes a 14-page special report that provides a number of insights into the Scandinavian model. Table 2.1 pretty much says it all. Of course, keep in mind that organizations are not countries. Also keep in mind, though, that a number of businesses are bigger than some countries. There are lessons we can extrapolate to our organizations.

The argument people make about the Scandinavian model is that these countries are relatively homogenous and so this kind of shared-destiny philosophy is more likely to thrive. This might well be true; but even so, our most diverse organizations are certainly much less diverse than any one of these countries. So, if these characteristics are associated with their success, organizations should almost certainly benefit from them. Another defining characteristic of these countries is they have some of the lowest wage inequality of any of the major economies. This is certainly a large part of their success and is something that organizations can learn from. The power of everyone sharing in the prosperity of the organization is a powerful motivator and means of engaging the workforce.

2.2.1. What Kinds of Organizations Could Benefit from a High Degree of Collaboration?

The short answer is pretty much every one of them. Based on case studies of organizations that do an especially good job with collaboration, knowledge-intensive organizations such as consultancies and other organizations do an especially good job of sharing the intellectual capital of their members. Oddly, although a substantial degree of collaboration exists between academics across institutions, there is generally not as much collaboration within academic institutions. Part of the problem with academic institutions is a tendency for each of the schools or departments to work as silos (something the private sector works hard to eliminate, with varying degrees of success).18

However, certain types of organizations would benefit to a greater degree than some others. For instance, knowledge-intensive firms that do not have collaborative systems in place are losing out on a substantial amount of potentially productivity and profit-enhancing information.

However, it is not only knowledge intensive firms with employees that are highly educated and skilled that can benefit from collaborative initiatives.

In fact, though, organizations can have a high degree of information capital, and this may exist in organizations where few employees have formal educational qualifications but that have access to a high degree of competitive information based on direct contact with customers, the products and production process, and the innovative process.

2.2.2. The Benefits of Collaboration

Nearly everywhere you look there is an increasing focus on collaboration. Knowledge-intensive firms have adopted open office plans that promote the free flow of information. Michael Bloomberg did this at Bloomberg LLC, and this is also the way in which he structured City Hall upon becoming mayor of New York. Firms have adopted a tremendous number of knowledge management software for the organization. There is a growing body of evidence that the better we are at collaboration, the better we are at coming up with great products and first-rate service.

2.2.3. The Bottom-Line Impact of Participative Decision Making

The question here is really this: Why bother with collaborative decisions making? Doesn’t this just slow things down? This is another topic I have researched and one that indicates that there are gains associated with greater involvement. In companies where collaboration is the norm, you are likely to get much greater investment (engagement by employees and stakeholders). A significant body of research indicates a strong link between employee involvement and the ultimate success of the enterprise.

Greater performance outcomes are associated with greater collaboration for a number of reasons. An engaged culture is critical to successful collaboration, and advanced analytics can assist with this. In addition to the substantial benefits associated with having employee feel more engaged, substantial efficiencies are associated with the flow of information. Those who are in direct contact with the products being built, with the services being delivered, with the customers—these people have access to asymmetric information, and without question, developing collaboration systems will lead to much greater and sustained competitive advantage.

Substantial research indicates a positive economic impact from collaboration. However, executives (or a small group of executives) often make big decisions based mostly on the information they have readily at hand. As discussed in Chapter 1, “Challenges and Opportunities with Optimal Decision Making and How Advanced Analytics Can Help,” decisions made this way often lead to outcomes that are far from optimal. Many decisions might be much better if they included as much information as possible. Collaborative decision-making systems are a vehicle to get the right information to the right people, who can then make the right decisions.

2.2.4. Organizational Culture

Considerable changes need to be made in organizations to make them places where employees are fully engaged and have an incentive to share what they know and are intent to stay (and so not spend time looking for the next job). Building such an organizational culture is worth the effort.

I have never liked the term organizational culture. This admission will get me in trouble with friends who conduct research on the topic, but it always struck me as simply too vague. For instance, with regard to the Challenger disaster, I recall hearing that a problem with the organizational culture at NASA ultimately led to the disaster. Honestly, to say that the culture caused the disaster doesn’t tell me much of anything. What actually led to the disaster were a very identifiable decision-making structures and specific incentives.

Essentially, corporate culture boils down to who does what and how do we motivate for productivity. All the activities associated with HCM revolve around these two questions. So, what do we mean specifically by the term analytical culture? What does this mean for analytics and decision making?

Let’s consider the Challenger example again. If the facts were acted upon, a tragic disaster could have been avoided. The question then arises: How do we design an organization and incentives so that it is only the facts that are acted upon? Blame is often assigned to the culture for all sorts of bad behavior and suboptimal results. Correct modeling, deep analytics, sophisticated algorithms, and statistical techniques are only part of the story. You also want to look at what specific behaviors are being rewarded and encouraged through incentives and who has the authority to make decisions.

2.2.5. Optimal Incentive Contract for Collaboration: Sharing Control and Return Rights

One of the most efficient incentive contracts is transferring the rights of ownership to nonowners. The two rights of ownership are control rights and return rights. Control rights are rights that come with ownership, which say that the owner has the right to do whatever he wants with the assets. Return rights are the rights to any returns, financial or otherwise, associated with the asset.

Sometimes the most efficient incentive contract is to transfer these rights of ownership to nonowners. In practice, this is done all the time. Executives are given a lot of freedom to make decisions about the assets of the organization, and they are in turn awarded some portion of the returns from the use of the assets. At the executive level, this sort of contract is generally a given. As we move to other positions in the organization, this might not be so common (ascribing both rights to employees).

There are many examples where one or the other of these rights is to some degree transferred to nonexecutive employees. There are many examples in which organizations provide opportunities for employees to participate in decisions or to manage assets that they are in direct contact with. The same applies to some degree of participation in the gains associated with the use of those assets. What is more unusual is for nonexecutives to have both of these rights transferred to them.

We need to explore three issues here:

• Transferring control rights without return rights does not provide an incentive to maximize the output from that asset (for example, either technological or human capital).

• Transferring the right of returns without transferring control rights means that employees will not have the authority to fully utilize the asset to obtain the maximum return. For example, they do not have the authority to cross-sell products.

• The most efficient incentive contract is when nonexecutives have both rights transferred to them. That is, they can cross-sell products and receive compensation for doing so.

2.2.6. Models of Collaboration

I have had the good fortune of being associated with two very collaborative and cooperative work environments. One was a research center at the London School of Economics (the Centre for Economic Performance; CEP). The other was the European headquarters of Cargill, Inc., located at that time in Cobham, Surrey.

They were both tremendously challenging and supportive cultures. They expected world-class cutting-edge social science research and world-class work, and no one in either place was shy about being as critical as they were supportive. Both of these places were filled with bright and hard-working individuals who valued competence and collaboration and a nice mix of work, play, and socializing. Strong ties developed between people, and people were happy to share their expertise with one another. I believe the cultures in these places were also the reason for their success. The CEP had two future Nobel Prize winners associated with it, and Cargill, Inc. is the largest private company in the world.

I have also worked where the environment was much more Darwinian—a place with little collaboration, where people routinely helped themselves to others ideas, took credit for others’ work, and were generally (no other way to say it) mean spirited. I liked the collaborative places better.

Some people excel in Darwinian workplaces. Microsoft has this sort of reputation. Microsoft has enjoyed great success (being a near monopoly has not hurt), but I do not believe this model maximizes the potential benefits from individual and collective private information.

One organization that typifies many of the positive aspects of what I am advancing here is the SAS Institute, located in Cary, North Carolina. It also happens to be one of the premiere makers of advanced analytical software.

2.2.7. The SAS Institute

The SAS Institute was established in 1976 by five co-founders and is one of the top providers of analytical software in the world.19 James Goodnight is the CEO and primary owner, controlling a two-thirds share of the company. SAS supplies many Fortune 500 companies with advanced analytical products.

Goodnight had worked for NASA, where employees were not trusted, executives were treated much differently from most workers, people did not talk to one another, and employee turnover was 50%. He vowed that if he were to start a company, things would be different; at SAS, they are.

Employees work a 35-hour workweek. There are on-site physicians, social workers, daycare, a gym—almost every service you can think of. The notion is that if daily tasks and concerns are taken care of, employees will be much more able to concentrate on their jobs.

One of the most impressive metrics is the fact that turnover is extremely low for a technology company. It hovers around 4%; the range for most technology companies is between 30% and 60%. It is estimated this low turnover rate saves the company $65 million annually, not including all the valuable information that employees take with them when they leave.

The organization is built upon a few important pillars, including the following:

• Invest heavily in getting the hire decision correct.

• Employees work a 35-hour workweek.

• No stock options, but profit sharing and bonuses.

• An annual employee and manager survey gauges morale.

SAS’s compensation systems are designed to foster interdependence. For instance, individual targets are not set for salespeople; instead, sales team targets are established. How well they do as a team determines how well the salespeople are rewarded. If you hire the right people, this serves as a powerful incentive. It provides an incentive to both help each out and to monitor one another.

Also note that no stock options are given. Instead, everyone participates in a company profit-sharing scheme, and everyone is bonus eligible. I believe they are doing exactly the right thing by not offering stock options. SAS is a private company owned largely by Jim Goodnight, and though it is entirely possible for private firms to put in place a phantom stock-option program, in this case it is unnecessary and would detract from the type of organization in place.

And, it has to be said, they are a hugely successful organization. They make great products (I talk about a number of them), have always been profitable, have never laid anyone off, always issue profit-sharing payments, and continue to grow. They have an interesting business model where they lease software to companies, with a yearly renewal of the lease; so, they are extremely responsive to their customers. This model has been a pivotal component of their success.

2.2.8. EMC|One

An excellent example of an initiative with a focus on both the organizational culture and the technology was in place at EMC. During the recession, when there was a focus on cutting costs, many EMC employees used a social media platform to suggest ways to cut costs and increase efficiencies. Changes that were made were more palpable to employees because they were part of the decision-making process, and because of the aggregation of information from many, the decisions themselves were better.20

2.2.9. Boston Scientific

Another firm that does an especially good job with collaboration is Boston Scientific.21 According to John Abele, one of its founders, one of the biggest challenges of developing a collaborative organization was not with the technology but rather with other factors. Abele emphasizes the importance of soft skills when it comes to something as critical as collaboration. Abele described a training course for a surgical method as follows:

Its real value, though, lies in the “wisdom of crowds” approach to advancing and proliferating the best new techniques. Software tools for collaboration abound, but it’s the soft skills that bring minds together.22

2.3. Advanced Analytics and Collaborative Decision Making

In the first instance, advanced analytics can assist with the determination of whether your organization, division, plant, department, or team could benefit from collaborative decision making. The decision framework should look like this:

1. Should you put in place a collaborative decision making process?

A. Degree to which employees have access to potentially productivity enhancing information (1–10)

B. The impact that information could have on output (1–10)

C. Decision required immediately (1–10)

2. What form of collaborative decision-making process should you put into place?

2.3.1. Challenges and Opportunities with Participative Decision Making

Enterprise content management (ECM) software makes much of knowledge management and collaboration possible. These systems hold the text, videos, social media, and other content that ultimately facilitates the sharing of this information. Interestingly, while much of IT spending decreased during the recession, spending on ECM increased. Spending increased by 5.1% in 2009, and 7.6% in 2010 (with revenue for ECM in 2010 of $3.9 billion). Estimates suggest that the annual compound growth in ECM purchases will increase at 11.4% through 2015.23

This is not entirely difficult to explain. Firms were doing their best to do more with less, so employees were (apparently) using whatever information source they could find. Organizations purchase these systems for a number of reasons, including the following:24

• Improve effectiveness

• Reduce operational costs

• Optimize business processes

• Achieve regulatory compliance and e-discovery goals

• Attract and retain customers

A number of excellent tools can assist with the collaboration process and ultimately assist with the making of much better decisions. Organizations are also starting to get much better at this. Organizations that can tap into the knowledge skills and abilities of their workforces are at a sizable competitive advantage over those that do not. Much of this is motivated by leveraging and retaining employee know-how. This is certainly the case in all knowledge-intensive firms such as consulting and research and in development-intensive industries. However, nearly all firms have institutional knowledge and experience that can be better leveraged.

You’ll note in other chapters a partial focus on the use of analytics to avoid problems. In this section, most of the focus is on optimization. The underlying assumption here is that a treasure trove of information resides within employees, and because of all the technologies that have come online recently, it is critical to get the incentives and the organizational structure right.

In settings where there is little incentive to share information across divisions or even with fellow employees, intergroup cooperation is much more likely than intergroup competition to promote positive outcomes. Competition between groups is fine, but you increase your chance of success substantially if a strong element of cooperation exists within the organization.

2.3.2. Software, Advanced Analytics, and Cooperation and Collaboration

Business intelligence software has some functionality referred to as collaborative BI. However, these systems are not as comprehensive as collaborative decisions-making platforms.25

Here are some impressive software products that can assist with this process:

Cogniti

Decision Lens (CMD)

IBM Cognos BI V.10.1 (CMD and collaborative BI)

Lyasoft: Lyza (CDM and collaborative BI)

Microsoft SharePoint (CDM)

Panorama Software: Necto

Purus Technologies: DecisionSurface (CDM)

SAP: SAP StreamWork (CDM)

2.3.3. Deep Q&A Expert Systems

Where can decisions associated with collaboration and knowledge management be assisted by AI and deep Q&A expert systems? Quite a number of potential problems and opportunities can be addressed and opportunities uncovered. Cray Computer’s YarcData has come out with a new computer called uRiKA (pronounced Eureka) that is similar to IBM’s Watson:

• Determinant of the primary method of decision making in your organization

• Determinant of the optimal decision-making strategy for your organization

• Recommended course of action

As stated previously, many vendors are operating in this space, and there is not enough bandwidth in this book to profile them all. Again, excellent sources of information for comprehensive evaluation of the various vendors and their products include Gartner Research and Forrester Research. The specific vendors I discuss are so profiled because they provide features that I believe are especially pertinent to HCM decisions, with one caveat for this chapter. Generally, when discussing other software in this book, the discussion focuses on information associated with HCM and related decisions. This evaluation will not be limited to only HCM decisions but will instead include a broader set of decisions. These systems usually contain a variety of business intelligence, including a variety of decisions support tools. With regard to collaborative decision making (CDM) software, as with much of the software I discuss, the primary obstacle to use is organizational culture issues. Top management might not care to give up the power that comes with control over decision making. According to Gartner,26 decisions associated with these systems include resource allocation, vendor selection, planning, and forecasting—all topics that are engaged with within HCM.

These systems facilitate the collaboration of many different parties to gather as much information as possible about an issue, ultimately using this information to suggest a more informed decision. Are the decisions better? This is a question that needs to be tested. Of course, with issues such as are they faster or slower, one would assume the decision making process may be slower, but this is not necessarily the case. Gathering all the information necessary to make a decision might seem to slow down the decision making, but making an informed decision certainly requires a substantial amount of research. This technology can speed up the process of obtaining the necessary information. So, the jury is out on this question of speed.

The quality of the decision is clearly a critically important aspect of the decision-making process. What about evidence that decisions using analytics are more robust? Again, there is a clear impact on performance associated with the use of advanced analytics. One such CDM system is the SAP StreamWork. The system is stand alone and allows whomever is the decision maker to find and select the best possible people to be included in the decision-making process based on information found in their profile. It provides signoff capability for those with various degrees of authority. It also captures the entire decision-making process and documents and stores it so that it can be revisited. The system interfaces with other SAP systems, making it possible to upload spreadsheets and dashboards, polls, pro/con tables, and a number of decision-making tools. In addition, it is possible to collaborate with external customers and clients, at the same time that confidential worksheets are kept confidential.

So, this in turn boils down to a simple question: What specifically can we do to see that our information capital is maximized? And how can advanced analytics assist with this process? If you want to be convinced that we do an especially lousy job with prediction, look no further than merger and acquisitions. We are truly terrible at predicting which firms are likely to work well in concert. Much of this boils down to incomplete and inaccurate predictive models.