2. Evolution, History, and Social Behavior: Our Wandering Road to the Modern Corporation

In his seminal novel I, Robot, Isaac Asimov spun tales of a future where humanoid robots were an integral part of our society. They cared for, worked with, and were controlled by humans. Robots had many different functions, but they all had one thing in common: the three laws of robotics.

These laws were designed to protect the robots’ human creators:

• A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

• A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

• A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Supposedly every other aspect of robot behavior was governed by their individual programming as long as it complied with the three laws.

However people noticed that robots had some other process guiding their behaviors. Muses one of the story’s protagonists in the film adaptation:

Why is it that when robots are stored in an empty space, they will group together rather than stand alone?

One could ask the same question of humanity. Why is it that two people in an empty room talk to each other rather than stare mutely at the floor? Why is it that we choose to work together rather than to work separately? Are these behaviors learned in our recent history, or are they something deeper, something more fundamental about being human?

Although there are certainly some general rules governing our behavior, fortunately or unfortunately we don’t have anything like the three laws of robotics to help people make sense of human groups. We need a basic understanding of how people evolved biologically and culturally to work together in order to uncover general principles around how people collaborate. These patterns will help identify what aspects of behavior are really important for collaboration and what data will be useful for analyzing today’s organizations.

Back to the Future

Since our pre-human ancestors climbed into the trees, we’ve been working in groups. Even for these ancestors, groups provided some fundamental advantages over individual action, the most obvious one being that you can better defend yourself when you’re part of a group. Simply more fists and weapons are available when you’re with others. You can also spread risk across many individuals in a group. When foraging for food, for example, your individual probability of success is fairly low. If you’re in a group that shares its food, however, even if you’re mostly unsuccessful, you’ll still be able to survive. Lastly, you can do bigger things when you’re in a bigger group. It might take three individuals to lift a rock that obscures a treasure trove of ants or other insects. Looking at our pre-human, chimp-like ancestors, then, seems like a perfect place to start in our investigation into the history of groups.

In the Shadow of Man

Let’s turn back the clock about three million years. Humans, homo sapiens, didn’t exist. In fact, most species that we know today didn’t exist. Our evolutionary ancestors of that time looked a lot like chimpanzees, from their sloping foreheads to their diminutive size. While fossil records are fuzzy at best, our ancestors come from one of the species from the genus Australopithecus, a group of short bipeds that could nearly chew through rock. Intellectually, however, their relatively small brains indicate that they were cognitively on par with modern gorillas and chimpanzees.

Our ancestors spent most of their days foraging, hiding from predators, and sleeping. Importantly, they were also able to stand upright. This one difference is believed to be one of the main reasons for our ancestors’ success, because it allowed them to walk and use tools at the same time.

We also know that these ancestors lived in groups. Considerable debate still exists about exactly how large the groups were and how they behaved. We really only have fossils to go on. Luckily, present-day analogues can provide some insight: gorillas, bonobos, and chimpanzees.

Gorillas

Most of us have seen gorillas in the zoo or on one of the many nature programs that populate the Discovery Channel. Despite their massive size, these ground-dwelling behemoths are primarily herbivores. Their large gut enables them to wolf down anything from fruit to pith, the woody stems of some plants.

Because their diet can accommodate most available food sources, gorillas don’t have to spend a lot of their time foraging. Gorillas typically travel around an area not more than a few miles in diameter, and on any given day they move less than a third of a mile. In contrast, the average human walks about five miles in a day.

Mountain gorillas typically live in small “troops” of 5 to 30 gorillas. As a group has to cover more distance to forage, smaller groups will gradually get larger. This is a direct result of the risk mitigation property of troops, because with more gorillas they can discover rich food sources more effectively. After a certain point, however, adding more gorillas to a troop has little effect on foraging efficiency.1

To understand that phenomenon, just examine the foraging process. Gorillas start off from a central point, going off in different directions in search of food. If they go more than a third of a mile without finding anything, then they’ll turn back. If there are too many gorillas, however, then this search becomes redundant. Different gorillas will be covering the same ground.

Gorillas could theoretically walk longer distances to find more food. However, the extra walking would increase a troop’s calorie expenditure, meaning that splitting into different groups would be more effective. In summary, for gorillas some benefit exists to being in a group, but after a group gets too big, those benefits decline.

Although gorilla and human societies are clearly not the same, their traits give us clues about how our ancestors might have lived and worked.

For us what’s interesting is that gorilla groups are most effective when they are relatively large, but not too large. There are simply no extremely large groups in gorilla societies, and this likely held for our ancestors as well. This evidence is also supported by some of our other ape relatives, such as bonobos.

Bonobos

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are one of our closest relatives in the animal kingdom, with our last common ancestor living some 6 million years ago. Also called the pygmy chimpanzee, bonobos probably separated from the common chimpanzee around 1.5 million years ago.

Bonobos contrast strongly with gorillas. They are much smaller, can form larger groups, and range over areas as large as 16 miles. This is necessary because they can’t eat as wide a variety of food as gorillas, and so depend on high-calorie foods such as fruit and meat to survive.

Bonobo society is actually quite similar to that of humans. They form large groups, sometimes more than 100 members, but they can forage in smaller parties of only 6 or 7 bonobos.2 These smaller parties often split off for days at a time, but they always come back to the larger group. This is a nice way to reap the benefits of large communities without exhausting the local food supply.

The local environment dictates how often this splitting occurs. When fruit is plentiful, bonobos stick together in one large group. There’s no need for them to go their separate ways scouring the area for fruit without the inherent protection of the larger group. When food is rare, small parties fan out across a wide area to explore and report any discoveries to the group. These foraging parties typically stay constant over time, but they’re not necessarily formed along familial lines. These small, cohesive foraging parties are essentially the core of bonobo social life. Interestingly, the society of their close genetic relative, chimpanzees, looks very different.

Common Chimpanzees

Common chimpanzees are physiologically very similar to bonobos, separated by only 1.5 million years of evolutionary history. Chimpanzees also form larger social groups, and have wide home ranges of up to 40 miles. These groups can range from 20 to more than 150 individuals, although typically they are in the lower part of that range.

Compared to bonobos, chimps live in an environment where access to food is much less certain. They can still break up into smaller foraging parties, but they have to cooperate with the larger group to survive. Although starvation isn’t a frequent occurrence in chimp societies, the dominance hierarchy is crucial in determining who gets food first, and therefore who is able to reproduce more easily.

Chimpanzees are also proficient hunters. They form complex hunting groups where different chimps take on different roles, constructing a sophisticated strategy for cornering small game. Some chimpanzees are assigned as chasers, who pursue the quarry. Blockers corral the prey until they reach the hiding ambushers, who catch and kill the animal. Importantly, food is shared not just among the hunting group but also with other nearby chimps.

This is a complicated activity, especially considering that chimpanzees aren’t able to communicate with a higher order language. They need to be able to understand this strategy, to plan and execute and change their plans on the fly. We typically associate these activities only with humans and with language, but clearly our ancestors must have engaged in these activities as well.

Importantly, however, a hard cap exists on group size for all apes. You simply don’t see apes in groups that are much greater than 150 individuals. Significantly, this is basically the same as the cap for humans, what is known as the Dunbar number.

The Dunbar number is the upper limit on the number of people a human being can know “well.” This concept was developed by the British anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who surveyed groups across human history and found that the most cohesive unit of coordination peaked at about 150 people. Small villages and military units had this common upper bound beyond which cohesion and performance started to break down.

Humans can naturally have larger groups, and some have put the Dunbar number as high as 230. Nevertheless, it is not an order of magnitude above the group size for chimpanzees. Rather we can see a steady change from our common ancestor to humanity’s current state.

Somewhere along the way, these groups became organizations, but finding an exact point in time when this occurred is difficult. Is there a significant difference between humans roaming the plains hunting large game and chimpanzees hunting animals in the forest? Suffice it to say that sometime within the last thousand years people began living in large enough groups to form cities, and it was during that time that a group that could be considered sufficiently close to an “organization” was formed.

You Say “Groups,” I Say “Organizations”

The definition of an “organization” is somewhat arbitrary—it has both similarities with and differences from a group. An organization is not simply a collection (or group) of people, such as everybody under the age of 25 or everyone who lives in an apartment building above the fifth floor. Clearly, when you think of an organization, the idea is that the people inside the organization are more connected to each other than one would expect by chance. In addition, this collection of individuals has to have a set of formal and informal processes that govern the behavior of the organization’s members. This distinguishes organizations as a subcategory of groups. In other words, all organizations are groups, but not all groups are organizations.

By this definition your group of friends is not an organization. They have no formal mechanisms for collective action. Although there will be informal consequences if one of your friends offends you, these rules aren’t written down anywhere. If they are, this is much more like a secret club, and you should seriously reconsider your choice of companions.

Of course, gray areas exist. Especially with the explosion of online communities, the boundary between groups and organizations has started to blur. As Tom Malone argues in The Future of Work, some of these online communities are most assuredly organizations. In his later work he singles out guilds in the World of Warcraft (WoW) as a prime example of what a modern organization can be.

For the uninitiated, the WoW is a Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (or MMORPG. Say that ten times fast). In WoW, players from across the world create an online persona that battles virtual enemies to increase their power and in-game money. This is primarily accomplished through quests, where you venture out for hours to eventually face a powerful enemy. Should you triumph, you are rewarded with valuable loot in the form of armor, weapons, and other virtual riches. As your character gets more powerful, these quests become increasingly difficult, to the point where you can’t complete a quest by yourself.

This is where the WoW guilds come in. In most of these quests, the prize at the end is indivisible. That is, there is only one prize and only one member of the party can claim it. Guilds create a formal structure around this process, where loot is parceled out quest by quest to the different guild members who participate, ensuring that everyone gets his or her fair share. Guild members have to coordinate effectively to complete these difficult quests, and their online activity as well as the reward process is highly structured.

This certainly clashes with our modern notion of an organization: people sitting in an office in two-piece suits filing form after form. However, when you strip away the outer layers, WoW guilds look pretty similar to other organizations.

The Linux development community is a similar example. Linux is a completely open source operating system, one of the chief competitors to the juggernaut of this space, Microsoft Windows. Whereas Microsoft develops Windows internally through its staff of programmers and engineers, Linux is developed by a worldwide community of people who aren’t paid for their effort. Although some formal processes are in place for Linux development—to be added to the core system code, one has to undergo a rigorous screening process—the notion of “employees” doesn’t exist here. It is an organization, but definitely a non-traditional one.

The distinction further blurs when you look at other online communities, such as the community of eBay merchants. These merchants rely on each other for accurate ratings of buyers and sellers in order to conduct their business. Merchants who violate customer trust need to be punished by the community. Otherwise, they risk diminishing the value of ratings for all sellers, driving buyers from the site. Although one might consider the rating system a formal process, the consequences of this system are harder to define. Still, these sellers need to create a vibrant marketplace to attract buyers, and they rely on each other for selling tips and policing scammers. Is this an organization? It’s certainly unclear.

Families are also difficult from a classification perspective. Although families live together and help each other informally, legal processes and protocols also exist around the definition of a family. If family members criminally abuse each other, a formal punishment is applied. Despite these conventional aspects of a family group, defining “family” as an organization is difficult.

All of these examples are to make the point that organizations don’t all look or act alike. Similar to our biological and cultural socialization mechanisms, organizations evolved over time, and there’s not a clear point that can be identified as the birth of the organization.

Individual < Tribe < City-State

Organizations are needed because they offer some fundamental advantages over more informal means of association. To get a sense of these advantages, look back at the ape troops discussed earlier. They are definitely groups, and although they have complex social hierarchies, there are no formal processes to speak of. Early humans lived in similar groups as well. Hunting in tribes that were made up of close relatives and families, technological innovation (that is, tool development) occurred at the pace of roughly one discovery every 10,000 years until about 8,000 BC.

This rate of discovery is essentially at a chance level because hundreds of generations were using tools with little improvement. As the human population increased, the chances simply became more likely that someone would think up a new tool. But something happened around 10,000 years ago. Humans started living together in groups that became too large to manage through informal means. For the first time in history, humans had crossed the Dunbar number. Codes of conduct had to be recorded, and rules had to be agreed upon. In short, people needed a government.

The concept of a government was a radical shift from the informal mechanisms which had dominated up to that time. From the first organisms to form in Earth’s oceans billions of years ago, life had developed on informal terms. Groups of animals would herd and act collectively, but these actions were heavily rooted in biological responses, honed through eons of evolutionary development. With the rise of civilization, humans realized the need for order to support our burgeoning aspirations.

Civilizations started out on a modest scale, with around 10,000 people living in early city-states. These city-states were foci of economic and agricultural activity, but tended to be fairly unstable. Smaller city-states would be subject to assault from larger neighbors, and, in fact, the first larger civilizations, such as Phoenicia and Babylon, were composed of a number of these city-states.

With so many people together in one place, city-states became places for the exchange of both goods and ideas, and this led to a much more rapid period of innovation. New technologies were emerging every hundred years or so, an order of magnitude faster than before. Recent work by Wei Pan and his colleagues at MIT have shown that the rate of innovation in cities is directly related to population density, which provides a clue as to why these early civilizations were so successful. They could create better technology, train better soldiers, and spread this influence to other affiliated city-states.

For city-states to run, however, they needed a number of basic services: roads, sanitation, and easily interpretable laws. The degree to which early societies were able to fulfill these needs had a direct impact on their success. The dominant civilization of the early historical era, Rome, provides a clear example of this relationship.

Do as the Romans Do

Like Greece before it, ancient Rome was a historical juggernaut. The Romans had scientific prowess that was second to none, delivering innovations such as concrete, the aqueduct, and indoor plumbing. Their army laid waste to their contemporary rivals, such as Carthage, the Gallic tribes, and the Kingdom of Pontus. From humble beginnings in 800 BC, Rome blossomed into a massive empire that spanned all of Europe and into the Middle East.

A central pillar of Roman might resided in their military, which cultivated absolute group cohesion above all else. Recruits were taken young, and joined together into groups of eight that stayed together for years. These teammates weren’t just training partners; they also played and lived together. A major tenet of the Roman training regime was to instill in you not just how special you were, but also how special all of your teammates were. The idea was that by turning your organization into your family, legionnaires would fight fiercely to protect each other and not worry about failing to return home to loved ones. After all, their loved ones were on the battlefield with them.

These cohesive ties permeated not just the military, but the ruling class as well. Roman government was a family affair, with nearly all major leaders related to each other in some way. However, as the empire expanded, maintaining this cohesion couldn’t be done through blood alone. New territories had to be similarly incorporated into the Roman fold, and this was done by literally developing a shared language. In their schooling the ruling elite spent nearly a decade studying the same four authors (Cicero, Sallust, Terence, and Virgil). Next they were instructed on proper language use, which meant speaking and writing exactly as the masters did centuries prior. Only the ruling class used such language, and it was immediately clear whether one was part of the “in-group” or an imposter. The cultural norms were simply too difficult to imitate.

Along with the empire’s expansion came changes in the highest seat of power—the emperor. Although no emperor ruled in Rome’s early history as a republic, later in its existence it became a critical role in the government. As the head of state, the emperor had to maintain close ties with regional governors because they had to understand how to execute the empire’s policies while at the same time stem revolt from their domain. This meant that the emperor was often traveling from city to city on official visits. As the empire grew larger, his absence from Rome grew longer and longer.

This travel soon became impractical, and it was deemed necessary, unofficially, to have at least two emperors governing different parts of the empire. However, because the empire was so large, emperors were still spending nearly all of their time traveling. Subjects all across the empire now considered themselves full Romans, with the inherent rights that came along with it. However, these different regions still had different customs, even different languages. Cohesiveness was threatened not only in the general populace, but in the governing class as well.

The fundamentals of Rome had changed. Although other factors were also involved, the Roman Empire soon unceremoniously collapsed under its own weight.3 Still, the principles of centralized control, cohesiveness, and formalized procedures endured in governments and organizations, remaining more or less unchanged until the 1800s and the explosion of modern industry.

Talkin’ ‘Bout a Revolution

The industrial revolution had a profound impact on management. Although most of us think of the industrial revolution as a period of technological innovation, changes in management over this period also still endure. In many ways, the genesis of what we recognize as a modern organization developed during this period, and the basic inventions that were developed formed the foundation for modern society. Modern paper manufacturing has its origins in the industrial revolution, as does gas lighting and the steam engine. Although these and other inventions had lasting effects, the steam engine is what would directly impact management.

Steam power immediately changed the mining industry and revolutionized transportation with the locomotive and steamboat. This transportation innovation was particularly important because it allowed people to travel extremely quickly over large distances. Rather than taking weeks to travel across Europe, the journey could be completed by train in a few days. The Atlantic could be crossed in a similarly short period of time, enhancing the flow of goods and ideas.

Companies could actually collaborate with people in different parts of the world, but this also brought about new challenges. How can you transfer effective manufacturing processes to different plants? What types of organizational structures are necessary to manage a diverse workforce spread across the world?

As goods and raw materials could be transported in large quantities relatively quickly, companies that could mass-produce goods thoroughly trounced smaller and less-nimble competitors on everything from quality to price. The factory was central to this overall strategy. Whereas, in the past, manufacturing had consisted of a few highly trained artisans laboriously constructing goods, factory production was made up of an army of low-skilled workers who each were specifically trained to complete a single task.

Division of labor was crucial for the effectiveness of a factory. By dividing production into small, independent steps, companies could turn out huge quantities of high-quality goods with these low-skilled workers. However, companies up to that point had not been set up to optimize those kinds of organizations. Well into the 1800s, most people worked in some form of master/apprentice relationship. In order to learn a trade such as carpentry, for example, you would literally live with a master for years, sometimes decades, in order to hone your skill. These businesses looked a lot more like art houses than companies.

New theories had to be developed to ensure that these factory workforces were as efficient and productive as possible. In the late 1800s, Frederick Taylor attempted to apply a rigorous analytical method to these manufacturing processes, developing a framework called scientific management—more commonly known today as Taylorism. His approach focused on measuring differences in performance between workers, observing how the most productive people did their job, and then standardizing that process and disseminating it across the organization.

Taylorism views people as cogs in a machine, with some cogs working better than others. In this model no room exists for a creative or knowledgeable worker. The goal instead is to squeeze the most amount of work out of your employees and ensure that inefficiencies are reduced as much as possible. This typically resulted in harder, longer work hours for the low-level employees and a huge amount of power in the hands of management.

Financially speaking, this approach made a lot of sense for factories of that time period. The vast majority of work was unskilled, and with a huge influx of immigrants into the West, creating a cohesive workforce would have been extremely difficult. When you have thousands of employees working on exactly the same process, discovering what makes people effective and transferring it across the organization is clearly important.

Chinks in Taylorism’s armor became apparent almost immediately. While pushing relentlessly toward increased efficiency, companies ignored the physical and mental needs of their workers. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Factory Act of 1819 magnanimously limited child labor to 12 hours per day. No minimum age was set for child workers until 1833, when children under the age of 9 were banned from working in the textiles industry.

Unfortunately, workers had no way to effectively protest these conditions. Many early attempts at strikes were easily put down by management. With a huge potential labor pool all clamoring for jobs, any workers who went on strike were summarily fired and replaced. Because these jobs were relatively unskilled, not many concerns existed about the cost of retraining.

This attitude galvanized workers to devise a response that would give them some leverage against management. Their answer was to form trade unions. The idea was that by banding together thousands of workers from a variety of disciplines, workers could effectively blockade companies that offered poor compensation or working conditions. Although unions were illegal in the early 1800s and severely discouraged later on, they gradually became a powerful force in organizational life.

This détente between workers and management continued for decades, rising in importance during both world wars and creating a manufacturing dynamo in the United States. People could look forward to working their entire lives for a single company, ensured of a job no matter the economic conditions. In fact, this system by and large still exists in some countries today, particularly in large companies in Japan.

From a practical perspective, this meant that you came to know the people you worked with remarkably well. Not only did you spend decades working with the same people, but people typically spent large amounts of their personal time with their colleagues. Blue-collar workers were expected to join unions and participate in union events, whereas white-collar workers joined social clubs and fraternal organizations. Ironically, this arrangement mimicked the way that people had worked earlier in history. Like the master/apprentice relationship and hunting tribes, the vast majority of workers in the mid-twentieth century were still heavily engaged with their colleagues.

Throughout this time, however, blue-collar workers were still treated as interchangeable parts. Even people in creative industries such as advertising and research were managed in much the same way as factory workers. Managing to enhance individual creativity and increase job satisfaction was a relatively novel idea well into the 1970s.

This model started to shift, however, when companies in Japan started to outcompete their Western rivals. Toyota introduced their eponymous Toyota Production System (TPS) in the late 1940s, but it didn’t rise to the attention of the international business community until the late 1970s. It was during this time that Toyota started to make major inroads into Western markets, eating market share from the likes of GM and Ford with superior quality cars and lower prices.

When managers and researchers looked for the impetus of this change, they stumbled upon the TPS. The TPS treats even front-line workers as an integral part of the development process. Workers are encouraged to develop their own methods and feed them back to the company. Toyota also urges their employees to think of themselves as part of a team, making sure that they’re involved and care about the people they work with.

The Toyota Production System was subsequently adopted in many industries across the world. Although saying that the popularity of this system directly led to widespread acceptance of the importance of collaboration would be an exaggeration, it was definitely a contributor. Companies started to think about the importance of getting people talking, of having a workforce that was constantly improving. Interestingly, this way of thinking didn’t lead to more talking face to face, but heavier use of a new technology called e-mail.

New Information, New Communication

E-mail was invented in 19714 as a way to quickly exchange information over the burgeoning Internet. At first e-mail was limited to academic circles and could only be used for text communication. It wasn’t until the 1980s that images and documents could be attached to a message, and that’s when e-mail really took off. Prior to e-mail, the only way to disseminate information across an entire company was to send a memo. E-mail is nearly instantaneously transmitted and enables a rapid back-and-forth between participants.

The adoption of e-mail and IT systems in general in the corporate world led to a rapid increase in productivity. Erik Brynjolfsson from MIT showed that from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, every dollar companies spent on new IT systems such as e-mail increased that company’s value by $12 by changing how people could collaborate at a massive scale.

Around the same time, the use of the Web for business was exploding. In the early ’80s, imagining the extent of the impact the Web would have might have been hard, but it was already having a profound effect on the way that companies worked. The Web truly democratized information gathering, giving employees sitting at their computers the ability to search through records and understand what was happening in their market in real time. This capability was one of the major catalysts for the ever-accelerating changes that have occurred in the way companies work.

The proliferation of mobile phones built on this trend, and in the early 2000s the “Crackberry” addiction had the corporate world in its grasp. Working in concert with the remote work trend, cellphone-based e-mail became a staple of business in the U.S., but it also changed the way people work. Today, we can be “always on,” and never truly separated from work. Although this availability allows organizations and employees to be more flexible, it also means they start spending more time on cellphones than talking to people face-to-face.

Instant messaging (IM) also has had an impact on work styles. Whether it happens on cellphones or on computers, IM solves many of the issues associated with e-mail. It’s a synchronous communication channel, meaning that you’re engaged in a conversation rather than in letter passing. This feature has made it an indispensable communication medium, particularly in the technology community, where IM has been integrated into most of the software and technological development systems in use today.

IMs are also more expressive than e-mails. Where proper e-mail etiquette demands that you choose words carefully because they can be easily forwarded to thousands of other people, IMs are more ephemeral, and misspelling words and using emoticons are the norm. IMs are also much better than e-mail at exchanging nuanced information. Because any chat is a conversation, you can quickly ask for confirmation on a particular point and ensure that you’re on the same page. However, IMs are not so good at connecting people who don’t know each other or at coordinating more than a few people at the same time.

Until recently, air travel was the primary way to make these new contacts. Today video conferencing has been put up as a cheap alternative. Companies inherently understand that face time is important, but in a globalized world, being physically present everywhere you’re needed is impossible. While in smaller organizations one-on-one video chats are fairly popular, in larger companies they’re mostly used for meetings. They are definitely a step above telephone calls, because they can convey facial expressions and give you a sense of the environment. However, issues exist with communication lag and the inability to look someone in the eye when you’re talking to them (you can look directly at the camera, but then you can’t see the other person on the screen).

Some technological fixes are available for these problems. A great example is Cisco’s telepresence solution. Its system is actually an enclosed room that consists of some chairs positioned around a half table attached to a massive screen. When the system is running, high-resolution cameras and speakers seamlessly connect you to an identical room in another location. The experience is quite remarkable, because it really does replicate the feel of a face-to-face meeting, minus the handshake. Unfortunately, this system costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and is still only good for scheduled meetings, not general socialization.

The Organization of Today

With the plethora of tools available today, people can work more effectively, communicate more quickly, and be flexible with the way they spend their time. Companies today are organized to take advantage of these tools, which enables rapid change in the products and services that they offer. In many ways, this has brought about changes in the workforce as well. You no longer can expect to be employed at a single company your entire life, because your skills in fast-growing fields such as engineering, design, and software development will most likely not be applicable in 10 years.

With this change in the employee-company relationship, people have become incredibly mobile in their careers. Switching jobs every few years is now a completely normal occurrence, and in some circles staying in one company too long is actually frowned upon. The tight cohesiveness of workforces that was the norm in previous decades is to a large extent a thing of the past.

With this increased job mobility, an increase in geographic mobility has followed. Because people are moving jobs about once every 10 years, over a typical 40-year career you’ll go through at least four jobs. This makes setting down roots in a city and expecting to stay there for your entire life difficult. In fact, over their lifetimes, U.S. citizens live in an average of three different cities.5 Compare this change to just a few decades ago, when the vast majority of people lived in the city of their birth for most of their lives.

The geographic mobility issue is compounded by what academia frequently calls the “two-body problem.” Whereas in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s rates of working women were relatively low, that percentage has skyrocketed over time, representing 47% of the U.S. workforce today.6 Now all serious relationships have a complicating factor: Both partners can find a job that requires them to move. Rather than having to concern ourselves with four job changes, now we’re looking at eight.

Some people think this “two-body problem” is new. Indeed, career mobility itself is quite a new concept. However, families across history have had to contend with both a man and a woman, if not children, working to make ends meet. Prior to the twentieth century, men and women working in those low-paying factories and on farms had to work long hours so that their meager wages could provide for their family. Although a small number of wealthy individuals could support a household with only one partner working, this was the exception rather than the rule.

The period between approximately 1920 and 1975 was a singular moment in time when one family member was the primary caregiver.7 This arrangement enabled men to socialize with one another after work, a necessary social glue that previously had been provided by shared experience at work and life together in villages in pre-industrial periods.

Now let’s shift back to the present. Old social norms that value collaboration and relationships have been revived, but coordination of jobs between partners has gotten much more difficult. These conditions, in large part, provided impetus for the burgeoning remote work movement.

The growing power of information technology provides people the option of working remotely. At first making heavy use of e-mail, telephone, and quick in-and-outs on an airplane, remote work today consists more of video conferences and instant messaging exchanges. While making use of cutting-edge technology to communicate, our methods of actually managing companies still look very similar to organizations from the 1950s. We rely heavily on formal organizational methods to deal with a workforce that has drastically more mobility, technical savvy, and a pressing need for collaboration to tackle increasingly complex work.

That’s where we are today. However, this historical and evolutionary perspective doesn’t provide insight into how organizations are actually run. Although we all work in organizations, most of us don’t know how they’re put together and what makes them tick.

This chapter has looked at how the concept of an organization developed over time, starting with informal groups, which grew into city-states and governments, and then more recently into the concept of corporations. Today, all three of these organizational forms still exist as families, modern governments, and millions of companies spread across the world.

Naturally, these organizations are all structured differently. People intuitively know that a school shouldn’t be organized like a government, nor should a family be organized like a company. This book focuses on companies, but even in that specific case, what “organizing” actually means can get fairly complicated.

(In)formal Processes

Broadly speaking, there are two aspects to managing an organization: formal and informal processes. Formal processes are all the things that are written down that determine how the organization works and how things get done. They are codified and ideally executed according to a written plan. There’s no room in these plans for variation between people or parts of the organization unless they are explicitly specified. Although this definition might be an idealized view of how companies operate, formal processes have been a major focus of management and management scholars.

Informal processes are everything else. They’re the things you learn (or don’t learn) by being inside the organization. Things such as culture, tacit knowledge, and social norms fall under the purview of informal process.

Let’s focus on a few of the most important processes, the ones that most people deal with every day.

Lingua Franca

Although it might seem trivial, as we shift toward a more global society, organizations have an important decision to make about what language they speak. While today English is essentially the international language, what language do people speak when an international company such as Google opens an office in a non-English-speaking country?

Adopting a lingua franca simplifies collaboration across cultural boundaries. Because everyone speaks the same language, you can naturally jump into conversations that you hear in the hallway or join another group’s meeting. This ease of collaboration is extremely important as a company first moves into a new country, because a number of people from the company’s headquarters are usually present to ensure that the new branch setup runs smoothly and to train new employees. However, enforcing a particular language also slows communication between team members from the same culture because fluency levels will vary.

Conversely, allowing local languages to be spoken speeds expansion in new locales after the initial setup phase because new employees can be trained in their native language. It also grows the available talent pool, because even in highly developed countries reaching a business level of fluency in a foreign language is difficult. The challenge in these organizations comes from trying to integrate workers into the fabric of the larger company. Employees from different branches have to communicate through formal channels to get things done due to language difficulties, and people speaking different languages won’t be able to informally chat around the office.

The lingua franca decision is often made by a strong collaboration between human resources departments and upper management, because these choices will drive the personnel dynamics of the company.

Dollars, Sense, and Workflow

Human resources departments across the world exist for a few specific purposes: to hire, evaluate, oversee, and pay employees. Each one of these represents a formal process in an organization. While this list isn’t exhaustive, these items serve as a good starting point for the purposes of this discussion.

Many people have a negative opinion of employee evaluation. The stereotypical view of evaluation involves employees nervously fidgeting as they wait for their boss to finish leisurely flipping through a performance report, at which point their boss rips into them and tells them why they shouldn’t be promoted, given a bonus, and so on.

However, evaluation isn’t just an opportunity for determining bonuses. It’s a way to help people figure out what needs to change to perform better and to understand what they’re doing well.

This point is usually overlooked. Too often, “evaluation” is used as a euphemism for “criticism.” This is unfortunate, because this is only part of what evaluation should be. A better term would be “feedback.” Good feedback helps people identify the things they’re doing wrong while at the same time pointing out strengths. For example, if you’re a good organizer but have trouble responding to requests in a timely fashion, then moving forward you have a very clear action plan. You should take a more active role in management and group leadership, because you’ll make the whole team more effective, but you should also make extensive use of your calendar to ensure you’re meeting your communication requirements.

Continuing on this point, evaluation is also used to figure out how roles should change over time. Maybe your skill set is better suited for another division, or you’ve been identified as high potential and will start being groomed for an upper management role. These assignments can’t be made on a whim. A regular, well-thought-out process should be in place for determining how to move people along in their career.

In most organizations the results of evaluation also directly impact how people get paid. Though it seems obvious that companies need to monetarily reward their employees, many careers focus relatively little on material rewards and instead make the organizational mission a reward in itself. This is particularly true in non-profit organizations. People in careers supporting worthy causes such as suicide prevention and caring for the homeless don’t bring home big paychecks, but because they are so passionate about the mission of the company, they’re willing to tough it out.

Determining incentives, however, is not straightforward. You can pay employees with commissions, pay them hourly, or hire them full time and pay bonuses. The type of compensation you choose is inextricably tied to the type of work people do and the type of work you want them to do.

We think of hiring people full time for a fixed salary as the default employment arrangement for white-collar careers. Fixed salaries are designed to make people more committed to an organization and ensure that changing work demands don’t become an issue. A company that hires a person full time is committing to his or her long-term development and signaling that this is someone they would like to be deeply involved in the organization. Although full-time employees aren’t eligible for overtime, they’re also not docked pay when things are slow. This represents a significant investment by the company, because if they consistently overestimate how much work needs to be done, the result is a lot of extra money spent on salaries.

Hourly employees, on the other hand, are much better for ramping up and down with demand. This pattern is common in retail during holiday seasons or at restaurants during high load times such as lunch and dinner hours. The downside of hourly wages is that employees aren’t as ingrained in the organization because companies are wary of providing extra training to workers who won’t necessarily be around long term. This arrangement also reduces the social integration of workers because they have to be focused on immediate output or risk losing their jobs. Schmoozing with coworkers by the coffee machine, unfortunately, nearly becomes a firable offense.

Bonuses and commissions are mostly used as a supplement to full-time and hourly arrangements, although in certain industries such as consulting and upper management, commissions and bonuses can make up the lion’s share of take-home pay. Bonuses fall into a few classes based on how they are awarded: individual performance, group performance, and company performance.

Many of us are familiar with the concept of individual bonuses. These bonuses are designed to incentivize people to complete their own work to the best of their ability and to go above and beyond the call of duty. Individual bonuses are typically based on an evaluation of your performance, either qualitatively by your superiors or through hard productivity numbers. A challenge with individual bonuses is that they tend to make people inwardly focused and disinterested in helping their colleagues, because the time they spend on those interactions doesn’t show up in their paychecks.

Commissions are a special case of individual bonuses. A commission gives you a percentage or flat dollar amount for every sale an employee makes. This applies in retail stores where employees get commissions for selling merchandise, all the way up to partners of large consulting firms, who typically get commissions by closing big customer contracts.

Group bonuses are designed to get teams to collaborate and hit overall performance targets. This is often useful when rewarding an individual on his or her contribution is impossible because it’s part of a larger product or service. By rewarding people at the group level, companies encourage people to work together to solve problems rather than look at just their own work. These bonuses are often used in software development to incentivize teams to hit their delivery date. Although an employee’s code might be only a small fraction of the overall software, he’ll try harder to jump in and help other parts of the team that are falling behind to get the bonus.

The downside to these bonuses is that they can lead to free-riding because lower-performing employees get paid the same as the high performers. Lower performers can be content to coast by, knowing that someone else will pick up the slack and they’ll still get their bonus. If this pattern of behavior becomes prevalent, it will severely demotivate the highest performers and further degrade group performance.

Company performance can also be used to determine bonuses. This practice is typically called profit sharing, and is designed to encourage collaboration not just across a specific team, but across the entire organization. Similar to group bonuses, the main idea behind profit sharing is that because your bonus depends on other parts of the company, you’ll try to branch out and pitch in across a wide variety of areas to ensure that the company succeeds. The problems with these bonuses mirror those of group bonuses, because there’s no good way to reward individuals based on their individual effort.

Even the type of pay people take home is a compensation lever. Rather than pay cash, companies could pay employees in stock. Startup companies usually take this route because they lack the cash to pay an employee’s full salary, but it’s also common practice for paying CEOs of large companies. By receiving stock rather than cash, employees are invested in the long-term future of the company, because if the company does well down the road, the stock will be worth more. This is an important point for CEOs because it ensures that they don’t sell off important parts of the company to make a quick buck while eviscerating the company in the long term. The downside is that employees usually can’t sell this stock for a long period of time, so for lower-level employees being paid in company stock doesn’t necessarily provide more incentive than a cash bonus or salary.

This discussion hasn’t even gotten into complicated pay schemes. Suffice it to say that companies can mix these different compensation schemes and make bonuses and salary hikes dependent on certain benchmarks or performance goals, but at the end of the day, it has to be simple. The more complicated a scheme, the less likely an employee is to understand it, so it will be less likely to have the desired effect on their behavior. The takeaway is that evaluation and incentive mechanisms are organizational levers that can change the way people work.

Having a process for making these decisions so that you know you’re rewarding the right behavior is important. That usually means that there should be a formal process around compensation decisions. Creating a workflow process around this and other organizational issues is a necessity if you’re going to run an effective company.

Every meeting that pops up on your calendar is part of a formal workflow process. Workflow means going through all the items on a checklist and making sure that you hit them in order. Although in most cases workflow doesn’t actually take the form of a checklist, most processes could be boiled down into this general framework.

Take budget planning as an example. The relevant people first need a brainstorming session to hash out the division’s needs for the year. Team members are each assigned to manage the budget for different areas, so before the next meeting they’ll have to accurately assess the needs of individual areas under their purview. After a few iterations, the division will be ready to present its budget proposal to the higher-ups, which will have a similar process of their own.

Especially in modern organizations, managing workflow has become critical. With people working on ever more complex projects, it’s necessary to set regular meetings and milestones and use reporting tools to make sure that everyone is coordinated. To ensure this coordination happens in a timely manner, an organization needs a defined set of people who can make these decisions. As in the budgeting example, defined contact points must exist so that things can keep moving forward. This is the purpose of the org chart, the company hierarchy.

When you think about the formal part of a company, the org chart is probably the first thing that comes to mind. Many factors go into figuring out the best way to structure these reporting relationships. Do you need to coordinate with different groups? How many subordinates can you reasonably oversee? This is one of the most important parts of the formal processes of organizations, and as you might suspect, there’s not one “right way” to do it.

Choosing a Company Structure

Making sure that the right groups are coordinating is essential for having a successful organization. These reporting relationships are a big part of that coordination. One of the reasons for the wild success of organizations in the early twentieth century was the hierarchies and systems of control they put in place. Knowing that a particular individual or group of individuals is ultimately going to have the final say is important because it helps you figure out who you need to talk to, who you’re accountable to, and who to go to when you need access to resources.

There are roughly four ways to structure these reporting relationships. Companies can mix and match them for different parts of the organization, but doing so is not the norm because it makes understanding the structure and managing the overall organization considerably more difficult. The basic idea is to pick the organizational structure that best supports the overall organizational strategy.

Functional Management

The functional management structural style organizes people around the type of work they do. Consider a global restaurant chain. Under a functional management regime, it would have a division for food procurement and distribution, a restaurant division that runs the individual establishments, a research and development division for coming up with new menu offerings, and a marketing division.

Functional management allows people to focus on their specific part of the business and tends to create economies of scale in terms of implementation and process optimization. In a functional organization, for example, all distribution activities are centralized, meaning that managers can figure out the best way to optimize distribution across different locations. One potential issue with functional management is that it tends to create solutions that aren’t tailored for specific markets. The only way different locations get different offerings is for that information to percolate up the hierarchy and then filter back down to R&D. Next these new innovations would have to go back up the chain from R&D and down to the restaurants for them to actually be implemented on the ground.

Divisional Management

Divisional management takes a different tack by organizing reporting relationships into self-contained units that include everything necessary to do a job. This structure is often used in industries that have to customize their products for different locations, like the restaurant and retail industries. A restaurant chain would look very different under a divisional structure. In this case, it would have a U.S. division, a European division, a Japanese division, and a South American division. Each division would have its own R&D, its own distribution channels, and its own marketing teams.

Divisional organizations tend to be much more flexible than their functional counterparts. Because they are specifically attuned to the needs and opportunities in their individual segments, different divisions can offer different products and services. Unfortunately, this often means a large duplication of effort across divisions because the company now has four R&D divisions, four distribution channels, and four marketing teams. Not only does this mean more staff, but also that coordinating campaigns and product development across divisions becomes extremely difficult.

Matrixed Management

The matrixed organizational form tries to combine the best of both the functional and divisional structures. This structure is organized across multiple dimensions to try to ensure coordination across different organizational silos but still maintain flexibility. The idea is that instead of reporting to just one manager, you now report to both a functional and a divisional manager. In the restaurant example, this could mean that an employee might have a boss from Japan and a boss from marketing.

A major benefit of matrixed organizations is that they allow for cost savings by centralizing different functions but can quickly innovate in different areas by aggregating information from across the company. The cost of this system is higher in two areas: complexity and time. Matrixed organizations are much more complex than their functional or divisional counterparts. Some organizations even matrix across more than two dimensions; for example, product, geography, and function. This complexity makes changing the organizational structure after it’s set up difficult.

As you can imagine, in a matrixed organization a lot of time must be devoted to communicating with bosses. This is not necessarily a bad thing, because coordination across organizational silos is usually extremely important. What this creates, however, is a lot of formal processing that has to occur before an initiative can start. Instead of a single boss giving the okay, now people from very different areas must be on the same page and approve the initiative.

Teams

Teams are often put up as a lightweight alternative to matrixing. Although teams have existed for a long time, only recently have they become a critical part of organizational structure. Traditionally sitting outside of the org chart, they are nonetheless a critical organizing factor and exhibit similar properties to matrixed organizations. Teams are typically tasked with accomplishing a specific set of objectives and often have an internal organizational structure along functional lines, although the scale is obviously smaller. In some organizations teams work on a specific project, such as a new aircraft or piece of software, and can persist for years.

The teams referred to in this discussion are small teams, because if a team gets beyond roughly 20 people, it becomes in essence a temporary division. Teams can be effective because they enable people from different backgrounds to collaborate and understand the strengths and challenges of different parts of the organization. When teams break out from traditional constraints, their output can be much more innovative than that generated within a specific division. This uniqueness, however, can also be a source of trouble. Getting team members on the same page might take a long time, if they ever do, and many teams find themselves working through individual conflicts rather than working together toward their real goal.

So, We’re Done Learning About Organizations, Right?

What’s interesting about the org chart is that most companies operate as if all communication occurs across its lines. From this perspective, if you don’t directly connect with someone, you don’t need to talk with him or her.

This is one area where traditional management theory breaks down. Many of us have worked, and we know that talking to other people on your team is also important. They don’t report to you, you don’t report to them, but you need to touch base and coordinate to be effective.

This coordination is an informal process. Your informal communication, be it chatting at the coffee machine or eating lunch together, are all important informal processes.

Informally Important

Informal processes are all about the culture of the organization. These aren’t things that you’ll learn about in a training manual. In fact, many of the things you’ll read about informal processes in a manual might be completely wrong.

A big part of informal processes are social norms, which guide your behavior not just at work but throughout your life. For example, if your family spends lots of time outside playing basketball, then your family has a social norm around sports. Social norms at school could involve reading during free periods or making a habit of interrupting class when the teacher is talking. Simply put, social norms are the things you do because everyone is doing them.

These norms are extremely important, because they keep behavior predictable and, ideally, optimized to some desirable end state. You know when you come into work that people won’t be sitting naked on their desks watching soap operas because there are norms against that. Similarly, you also know that your colleagues are going to get that urgent report done because the norm is to complete the work even if people have to do it from home.

These social conventions determine important things about the organization, like where people eat lunch, how employees talk to each other, and what “business casual” really means. What’s interesting about these norms is that they often emerge spontaneously. Although managers might try to shape them, doing it is notoriously difficult because quantifying these things is so hard.

For example, consider where people eat lunch. A lot of factors contribute to your decision about where to eat. If everyone eats at their desk, then chances are you’ll eat at your desk. If everyone goes out to eat, then you probably will as well. You might also go out to lunch because your friends do, or because food in the cafeteria is so good (or cheap—cheap food being a great motivator).

Ironically, the formality of a workplace is an important aspect of organizational culture. This appears in not only the way people talk but also in the way they dress. These norms are often partially formally specified, in terms of dress codes and gossip policies, but the way they actually manifest themselves is by and large an informal process.

Talking about personal lives at work can be a major point of contention within a company. Having a strong norm against discussing personal situations can ensure that messy personal issues don’t take over the office and helps people focus on their work. On the other hand, this creates barriers in the company that can negatively impact mental health and performance. For example, if someone were having marital problems, it would invariably affect them at work. Without being able to talk about this with colleagues, the person’s stress level could increase and have negative effects on the whole team.

The formality of dress can have a similar effect. Although suits and “professional” dress can promote a respectable atmosphere for clients, they also promote conformity. Researchers have found, for example, that pedestrians are more likely to violate traffic laws if they see a person wearing a suit doing it versus someone in jeans and a t-shirt.

The Social Network

The discussion so far has tiptoed around what actually constitutes the social fabric of an organization. This chapter has covered in vague terms what groups and relationships are, but really hasn’t pinned this down into something measurable. Social scientists for centuries had the same problem, and it wasn’t until the 1930s that a solution was posed in the form of an oft-abused term: social networks.

The social network construct is a way for scientists to get a quantitative understanding of the relationships between groups. An example can help explain exactly what a social network is and why it is such an important tool.

Imagine five people, represented in Figure 2.1 with dots.

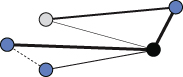

Now, suppose you want to show that one person is friends with another person. A simple way to do this is to draw a line from one dot to another as shown in Figure 2.2.

If you wanted to show not just one relationship, but lots of relationships, you would get a diagram that looks something like Figure 2.3.

Now suppose you didn’t want to look at friendships, but who talks to each other. In that case, the diagrams might differ from week to week. One week you could get a pattern like you see in Figure 2.3, but the next week you could get something like that shown in Figure 2.4.

Taking this example further, what if you wanted to show not just who talks to whom, but also how much they talk to each other? You could do this by making the lines thinner or thicker depending on who was talking, as shown in Figure 2.5 (two of the nodes are shaded to use in a later discussion).

A few questions can be answered when looking at this diagram. The first is simple: How many people does each person talk to? You can answer this by counting the number of lines touching each dot. In a social network, this is called the degree. The light gray dot has a degree of two, whereas the black dot has a degree of four.

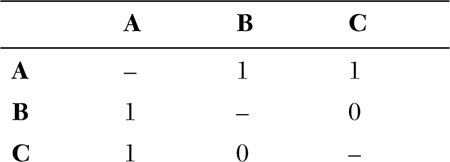

Degree, however, is a simple measure for which you don’t really need a social network. For more complicated measures, you need some way to mathematically represent a network. Luckily, these kinds of diagrams have been used in a field of mathematics called graph theory. In graph theory, dots and lines are represented in a matrix, which is essentially a table of numbers. To understand what this looks like, let’s consider a very simple social network, shown in Figure 2.6.

In this graph the dot (or node in the mathematical jargon) A is connected to nodes B and C. Mathematically, this is represented by the following matrix:

In this example, the matrix is just the grid of nine entries in this table. Entry BA is 1, because you know that nodes B and A talk to each other. BC and CB, however, are set to 0 because B and C don’t talk to each other. In this matrix, you don’t pay attention to the entries AA, BB, and CC because that would represent someone talking to themselves (which, while humorous, isn’t something discussed here).

Importantly, these entries don’t have to be just one and zero. Suppose you want to show how much people communicated with each other? You could then have a matrix where the entries represent how many minutes each person talked to each other. For example, Figure 2.7 would be represented by the following matrix:

In this matrix you can see that A and B talk for 20 minutes, while A and C talk only for 3 minutes. This representation makes an easy task of encoding not just who talks to whom, but also how much. Time, however, isn’t easily captured here. To look at a network over time, you would actually have to look at many matrices, one for each time period.

With the matrix concept under your belt, let’s see what you can do with this data. You now know about degree, and a computer can easily calculate degree from a matrix. It just counts how many non-zero entries are in that node’s row.

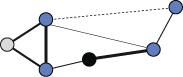

However, a matrix allows you to do so much more. One major concept used in this book is cohesion. Cohesion is a way to measure how tightly knit someone’s network is. Conceptually, it measures how much the people you talk to talk to each other, placing more emphasis on the people you speak the most with. Take, for example, Figure 2.8.

Compare the networks of the gray and black nodes. The light gray node talks to two other people, who spend the vast majority of their time talking to each other or the gray node. The black node, on the other hand, talks to two people who don’t talk at all to each other. The cohesion of the light gray node would be very high, while that of the black node would be 0.

The last big concept used in this book is the idea of centrality, specifically betweenness centrality. Take a look back at Figure 2.5.

You immediately notice that there are two groups of people, and the black node is the only one who connects the two groups. This makes that person very important, because they’re the only way for information to get from one group to the other. Later chapters will discuss the implications, but for now it’s not hard to understand that people in these high centrality positions are generally more powerful, influential, and learn about things faster than other people.

Mathematically, you measure betweenness centrality by trying to make “paths” through the network. Imagine that the nodes represent cities and the lines represent roads between the cities. You can only drive on the roads that are already there, and for the purposes of this discussion consider the roads to all be equal in length. To get from one place to another, you just need to find the path that takes you on the smallest number of roads.

Centrality measures what percentage of time each node is on that shortest path for every pair of nodes in the network. In the example, every shortest path from a node in one group to a node in a different group would have to go through the black node, and so its centrality would be by far the highest.

Applying this concept to organizations, you can make a social network diagram with all the people who work in a company. As you might imagine, the pattern of these connections has profound implications for how information flows and how work gets done. Studies throughout this book will use the Sociometric Badges, e-mail data, and other information to measure these social networks and investigate their relationship with outcomes that people care about, such as productivity and job satisfaction. After all, despite the discussion of these organizing mechanisms and informal processes, that’s what you want to improve.

Organizing the Path Ahead

This chapter covered the basics of formal and informal processes, but by no means was the discussion exhaustive. To adequately go into all that detail would take another book.

This chapter does, however, lay the framework for what’s to come. Chapter 1 covered how data can correct some of the problems inherent in how we understand organizations today. Now that you have a sense of what fundamentally comprises a company, you can venture into the world of organizations armed with a better understanding of that nebulous concept and, more importantly, data.